Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major global health challenge, intensified by the rise of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The bacterial cell division protein FtsZ, a key GDPase required for cytokinesis, represents a promising target for novel anti-TB therapeutics. This study aimed to identify potential FtsZ inhibitors among marine fungal metabolites using molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and MM/GBSA analyses. Docking was performed with AutoDock Vina v1.2.0, followed by 200 ns MD simulations using Desmond to evaluate complex stability. Among 100 screened metabolites, Xanalteric acid II showed the strongest binding affinity (− 10.9 kcal/mol), interacting with Arg140 and Thr130 within the active site, outperforming the co-crystallized ligand (− 9.1 kcal/mol) and moxifloxacin (− 7.7 kcal/mol). The FtsZ–Xanalteric acid II complex exhibited stable RMSD and compact radius of gyration throughout the simulation. MM/GBSA analysis revealed a strong binding free energy (ΔG_bind = − 74.77 ± 4.95 kcal/mol), dominated by van der Waals and lipophilic interactions. PCA, FEL, and DCCM analyses confirmed the structural rigidity and energetic stability of the complex. These findings highlight Xanalteric acid II as a promising marine-derived inhibitor of FtsZ and support the potential of marine metabolites in developing next-generation anti-TB agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), remains one of the leading infectious diseases worldwide, posing a major threat to public health and socioeconomic stability1. According to the WHO Global Tuberculosis Report 2024, about 10.8 million people worldwide developed active TB in 2023, and TB caused approximately 1.25 million deaths globally. Strikingly, the disease burden is heavily concentrated: roughly 45% of new cases occur in the WHO South-East Asia Region, and another ~ 24% in the African Region, with the Western Pacific Region also substantially affected. At the national level, India alone accounts for about one-quarter of all global TB cases. These numbers illustrate that TB remains a major public-health challenge — especially in Asia and Africa — and highlight the urgent need for novel therapeutics targeting drug-resistant and hard-to-treat TB2,3. Alarmingly, approximately 410,000 cases were reported as multidrug-resistant (MDR-TB), reflecting resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampicin—the two most potent first-line anti-TB drugs4. The growing prevalence of MDR-TB and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) continues to undermine global TB control programs and emphasizes the urgent need for novel therapeutic agents with alternative mechanisms of action5,6.

One promising avenue in anti-TB drug discovery involves targeting essential bacterial proteins responsible for cell division7. Among these, the filamenting temperature-sensitive protein Z (FtsZ), a bacterial homolog of tubulin, plays a crucial role in cytokinesis8,9. FtsZ polymerizes in a GDP-dependent manner to form a dynamic Z-ring at the future site of cell division, recruiting downstream division proteins essential for septum formation and cell wall biosynthesis10,11. Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization or GDPase activity leads to abnormal cell morphology and growth arrest, ultimately causing bacterial death12. Importantly, FtsZ is highly conserved among bacterial species but structurally distinct from eukaryotic tubulin, making it a selective and attractive target for antibacterial drug development13.

It will need new medications with shorter durations of action and fewer adverse effects for effective treatment of MDR/XDR14. Marine fungi have recently emerged as an abundant yet underexplored source of structurally diverse and biologically active secondary metabolites. The extreme and nutrient-limited marine environment drives unique evolutionary pressures that enable these fungi to biosynthesize chemically unprecedented scaffolds, including alkaloids, terpenoids, polyketides, and peptides with mechanisms distinct from terrestrial organisms15,16,17. Such chemical novelty is particularly relevant for TB, where the rise of MDR and XDR strains underscores the urgent need for molecules with new modes of action18. Numerous studies have reported that marine fungal metabolites display promising antimicrobial potential, positioning them as a valuable resource for developing new anti-TB agents19,20. Therefore, exploring marine fungal metabolites offers a strategic opportunity to identify structurally innovative, pharmacologically rich candidates for next-generation anti-TB therapeutics.

Advancements in computational drug discovery have further accelerated the identification of promising inhibitors from natural sources. In-silico techniques such as molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations21, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicity (ADMET) analysis allow rapid screening and evaluation of large compound libraries while minimizing experimental costs and time. These approaches also enable a deeper understanding of protein-ligand interactions and help prioritize lead molecules with favorable pharmacokinetic and safety profiles22. In this study, we employed an integrated in-silico approach to identify potential FtsZ inhibitors among marine fungal metabolites. The workflow combined molecular docking to predict binding affinities and molecular dynamics simulations to assess stability and conformational behavior. Through this comprehensive computational analysis, we aimed to identify novel marine-derived scaffolds with potential inhibitory activity against FtsZ, thereby contributing to the discovery of new candidates for combating multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

Materials and methods

Ligand selection and Preparation

A total of 100 marine fungal metabolites were compiled from reputable natural-product sources, including CMNPD (https://www.cmnpd.org/)23, COCONUT 2.0 (https://coconut.naturalproducts.net/)24, and published studies reporting metabolites isolated from marine-derived fungi25,26,27,28,29,30. Metabolites were partially selected based on their reported antibacterial activity31,32,33,34,35. Additional filters—such as removal of duplicates, exclusion of inorganic/metal-containing compounds, and structural completeness—were applied to ensure high-quality input for docking. Their three-dimensional structures were downloaded from the PubChem database in SDF format, and some of the structures were drawn manually using ChemDraw 23.1.1. The energy was minimized using the MMFF94 force field in Open Babel v3.1.136. The co-crystallized ligand (GDP) from the FtsZ structure and the reference antibiotics Moxifloxacin and Linezolid were used as control ligands for comparison37. All ligand structures (100 metabolites + 2 reference drugs + one co-crystal ligand = 103) were converted into PDBQT format using Open Babel v3.1.1, ensuring the addition of Gasteiger charges and defining torsional degrees of freedom for each metabolite38.

Protein Preparation and validation

The crystal structure of the Mtb FtsZ protein (PDB ID: 1RQ7)39 was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1RQ7). The structure was chosen due to its high-resolution crystallographic data and the presence of a native co-crystallized ligand bound to the GDP-binding domain, which defines the catalytic pocket. All water molecules, heteroatoms, and non-essential cofactors were removed using Discovery Studio Visualizer 202140. Protein minimization in UCSF Chimera v1.16 was performed using the AMBER ff14SB force field under an implicit solvent model41. Hydrogen atoms and Kollman charges were added using AutoDock Tools (ADT) v1.5.7. Protonation states and residue ionization were retained as present in the PDB structure (AutoDockTools does not alter protonation automatically). Missing atoms present in the PDB file were automatically rebuilt by ADT, and the final optimized structure was saved in PDBQT format for docking simulations42. The stereochemical quality and structural integrity of the protein model were validated using a Ramachandran plot generated by SAVES v6.1 web server (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/)43. It provides the PROCHECK-based results44.

Active site identification

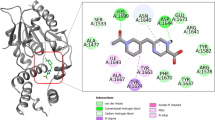

Active site identification and grid box generation were conducted in Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021. The active site of the FtsZ protein was identified based on the position of the native co-crystallized ligand and previous structural studies describing the GDP-binding pocket. The catalytic cavity was defined to include key residues such as Gly18, Gly19, Gly101–107 (catalytic residue), Thr106, Arg140, Asp184, and Asn163, which are known to participate in nucleotide binding and polymerization (Fig. 1)39. The grid box was generated to cover the entire nucleotide-binding pocket with the following center coordinates: center_x = − 6.63, center_y = 36.02, center_z = 7.27, and dimensions size_x = 20 Å, size_y = 20 Å, size_z = 20 Å. Docking was conducted with an exhaustiveness of 8 and an energy range of 4 kcal/mol.

Three-dimensional structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis FtsZ highlighting major secondary-structure elements. The crystal structure of FtsZ (PDB ID: 1RQ7) is shown with its secondary-structure components annotated. α-Helices are represented in red, β-sheets in yellow, and loop regions in green. The bound GDP molecule is displayed in stick representation (blue), marking the nucleotide-binding site. The visualization illustrates the spatial arrangement of helices, sheets, and flexible loops that contribute to FtsZ’s catalytic function and conformational dynamics during polymerization.

Molecular Docking simulation

Validated docking simulations were performed for all 100 marine fungal metabolites using AutoDock Vina v1.2.045. The docking grid was centered on the coordinates of the native ligand-binding pocket to encompass all key amino acids involved in GDP binding. The grid box dimensions were optimized to ensure the inclusion of the complete binding cavity. Each docking run generated 10 poses per ligand, and the best conformation was selected based on the highest binding affinity (kcal/mol) and favorable orientation within the pocket.

Post-Docking analysis

We screened 100 metabolites by docking; from these, 6 representative metabolites are presented in the result section, and the full docking results for the remaining metabolites are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The ten compounds shown in the result section were selected objectively by docking-score ranking (top 6 by docking score). The protein–ligand interactions, including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic interactions, were visualized using Discovery Studio Visualizer 2021. Comparative interaction studies were carried out for the top-scoring marine fungal metabolites, the co-crystal ligand, and Moxifloxacin to identify conserved binding residues.

Docking protocol validation

To validate the protocol, the co-crystallized ligand in 1RQ7 was extracted and re-docked using the same grid parameters. The top-ranked pose showed a close alignment with the native crystallographic conformation (low root mean square deviation, generally < 2Å), confirming the reliability and reproducibility of the docking setup46. All ligands in the study were subsequently docked using this validated protocol. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) between the conformations was calculated using PyMOL v3.147.

MD simulation procedure

System Preparation

The MD simulations were performed using the Desmond module implemented in Schrödinger Release 2023-4 to evaluate the structural stability and dynamic behavior of the FtsZ–ligand complexes. The top one docked complex, Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ, was selected based on its superior binding affinities and key active site interactions observed in docking analysis. The Protein Preparation Wizard in Maestro was employed to optimize the structures by assigning bond orders, adding missing hydrogen atoms, and optimizing side-chain orientations at physiological pH (7.4). All water molecules present in the crystal structure were removed before solvation48.

System Building and solvation

Each complex was embedded in an orthorhombic simulation box and TIP3P solvation, ensuring a 10 Å buffer distance from any protein atom to the edge of the box. To neutralize the system, counter ions (Na⁺ or Cl⁻) were added, and an ionic concentration of 0.15 M NaCl was maintained to mimic physiological conditions. The OPLS4 (Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations 4) force field was applied to all components, ensuring an accurate representation of atomic interactions49.

Energy minimization and equilibration

Energy minimization was conducted using the Steepest Descent algorithm until the system reached a convergence threshold of 1.0 kcal/mol/Å to remove steric clashes and relax the geometry. Following minimization, the systems underwent a two-step equilibration protocol consisting of a short NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) for 1 ns and an NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) for another 1 ns at 300 K and 1 atm pressure using the Berendsen thermostat and barostat. The Martyna–Tuckerman–Klein chain coupling scheme was applied to ensure stable temperature and pressure regulation throughout the simulation50.

Production MD run

The equilibrated systems were subjected to 200 ns production MD simulations under periodic boundary conditions using a 2 fs time step. The trajectory data were recorded every 10 ps for further analysis51.

Trajectory and stability analysis

The trajectory outputs were analyzed using the Simulation Interaction Diagram (SID) tool in Desmond. The RMSD of the Cα atoms was calculated to evaluate the overall structural stability of the protein–ligand complexes during the 200 ns simulation. The root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values were computed to assess the flexibility of individual amino acid residues, particularly in the binding pocket. Hydrogen bond occupancy, radius of gyration (Rg), and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) were also analyzed to gain insights into conformational stability, compactness, and solvent exposure of the complexes52.

Free energy landscape (FEL), principal component analysis (PCA)

The FEL and PCA analyses were conducted to explore the conformational dynamics and collective motions of the FtsZ–Xanalteric acid II complex during the 200 ns molecular dynamics simulation. The trajectory data were processed using the Simulation Interaction Diagram (SID) tool in Desmond and further analyzed with the Bio3D and ProDy packages integrated in Schrödinger Maestro. PCA was performed by constructing a covariance matrix of the Cα atomic fluctuations and diagonalizing it to obtain the principal eigenvectors representing dominant motion modes53. The first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were used to construct the FEL, which was generated according to the Gibbs free energy equation, G = –RT ln P, where P represents the probability density of conformations54.

Probability density function (PDF), and dynamic Cross-Correlation matrix (DCCM)

The PDF was derived from the population distribution of conformers along PC1 and PC2, providing insight into conformational flexibility and stability. The DCCM was computed based on the cross-correlation coefficients of atomic displacement vectors to identify correlated (positive) and anti-correlated (negative) motions among protein residues55. These analyses collectively elucidated the conformational stability, cooperative dynamics, and energy landscape of the FtsZ–ligand complex56.

Binding free energy calculation

Post-simulation, the MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area) method implemented in Prime (Schrödinger) was employed to estimate the binding free energies (ΔG_bind) of the FtsZ–ligand complexes. For MM/GBSA calculations, 1003 frames were uniformly extracted from the 200-ns MD trajectory (sampling interval ~ 200 ps) and used to compute the average binding free energy. The binding free energy was computed according to Eq. 1.

Where Gcomplex, Gprotein, and Gligand represent the minimized free energies of the respective states57.

Physiochemical properties and toxicity prediction

Physicochemical properties of Xanalteric acid II and Apiosporamide were obtained using the ADMETlab 3.0 web server58, and radar plots were generated to compare each compound with standard drug-likeness thresholds. Acute inhalation toxicity was predicted using the STopTox web server59. Organ-specific toxicity, including hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and carcinogenicity, was assessed through the ProTox 3.0 platform, which also provided applicability domain evaluation and fragment contribution analyses60. All predictions were performed using default parameters, and results were compiled to evaluate overall drug-likeness and toxicity profiles.

Results

Active site and protein validation

The active site of the FtsZ protein was successfully defined by generating a grid box that encompassed all catalytically relevant amino acid residues (Fig. 2A). The grid was strategically positioned to cover the GDP-binding pocket and adjacent loop regions, ensuring comprehensive coverage of potential ligand-interacting residues. The binding site topology revealed a well-defined cavity characterized by polar and non-polar residues, providing a suitable environment for ligand accommodation and interaction. The structural validation was performed through Ramachandran plot analysis (Fig. 2B). The results indicated that 95.5% of the residues were located in the most favored and 4.5% additionally allowed regions. No amino acids fell within the disallowed regions. This distribution confirmed the stereochemical quality and structural integrity of the FtsZ protein model, validating its suitability for subsequent molecular docking and simulation studies.

Binding site interactions with native ligand

The binding site analysis of the FtsZ protein with its native ligand revealed several key interactions contributing to complex stability (Fig. 2C). The co-crystal ligand (GDP) was accommodated within the GDP-binding pocket and established multiple hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and electrostatic interactions with catalytically relevant amino acid residues. Strong hydrogen bonding interactions were observed with Asp184, Asn22, and Arg140, stabilizing the ligand within the active cleft. Additional interactions with Glu102, Glu136, and Gly18–Gly19 further reinforced the ligand’s orientation and conformational stability. Several glycine residues (Gly104–Gly107, Gly17) and Thr106 formed van der Waals or weak polar contacts, providing a supportive environment around the phosphate and ribose moieties of the ligand. Hydrophobic interactions involving Phe180 and Ala183 contributed to the overall binding affinity, enhancing the stabilization of the aromatic region of the ligand within the hydrophobic pocket. These interactions highlighted the structural complementarity between the FtsZ binding cavity and its native ligand, validating the reliability of the docking grid and confirming the suitability of the identified active site for virtual screening of marine fungal metabolites.

Molecular Docking analysis

Molecular docking of one hundred marine fungal metabolites was carried out to identify potential inhibitors targeting the FtsZ protein (PDB ID: 1RQ7). Among these, only compounds exhibiting binding affinities below − 9.0 kcal/mol were considered for detailed analysis, while the remaining docking results were provided in the supplementary file (Table 1S). The docking outcomes revealed that several metabolites displayed stronger binding energies compared to the native co-crystallized ligand (–9.1 kcal/mol) and the reference drug moxifloxacin (–7.7 kcal/mol), suggesting a higher affinity for the active site of FtsZ (Table 1).

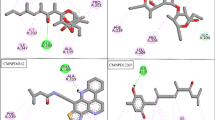

The top-ranked compound, Xanalteric acid II, exhibited the most favorable binding energy (–10.9 kcal/mol), forming two hydrogen bonds with Arg140 and Thr130, both of which are crucial residues in the GDP-binding region (Fig. 3A). Apiosporamide also demonstrated a strong affinity (–10.6 kcal/mol) by forming six hydrogen bonds with residues Thr42, Thr106, Gly19, Gly101, Gly104, and Arg140, indicating its potential to disrupt FtsZ polymerization (Fig. 3B). Alterporriol C showed a binding energy of − 10.1 kcal/mol, stabilized through hydrogen bonding with Gly18, Gly19, and Thr106, which are known to contribute to nucleotide-binding stabilization (Fig. 3C). Similarly, 5-epi-Asperdichrome and Verruculogen both exhibited a binding energy of − 9.1 kcal/mol, forming multiple interactions with residues such as Asn41, Ala70, Gly105, Gly107, Thr106, and Arg140, comparable to the co-crystal ligand’s interaction pattern. Tajixanthone hydrate, with a docking score of − 9.0 kcal/mol, showed hydrogen bonding with Arg140 and Asp184, which are essential for catalytic activity and protein conformational stability. The consistent involvement of residues such as Arg140, Thr106, Gly18–19, and Asp184 across the top-scoring compounds indicated a conserved binding region within the FtsZ active site. The observed interactions suggest that these marine fungal metabolites could effectively occupy the GDP-binding pocket, potentially impeding FtsZ polymerization and subsequent bacterial cell division.

The co-crystal ligand (Figs. 3D and 4A) exhibited a strong network of hydrogen bonds with Gly101, Gly105, Gly107, Thr106, Asn163, Ala70, and Arg140, in addition to hydrophobic interactions with Phe180, confirming its stable orientation within the GDP-binding pocket. The Linezolid compound (Fig. 4B) formed multiple hydrogen bonds with Thr106, Arg140, Gly17, Gly104, and Gly107, closely mimicking the interaction pattern of the native ligand. The strong electrostatic and polar interactions with Arg140 and Thr106—key residues responsible for FtsZ polymerization—suggested its potential to interfere with GDP-dependent filament formation. In comparison, Moxifloxacin (Fig. 4C) established hydrogen bonds with Thr106, Ala70, Gly101, Glu136, and Arg140, along with π–π stacking with Phe180, indicating a moderate binding affinity relative to the native ligand.

The heatmap visually represents the binding affinities of 103 compounds, where color intensity indicates the magnitude of binding scores (Fig. 1S, supplementary file). Cooler colors (blue to cyan) correspond to stronger binding affinities (more negative scores, around − 9.0 to − 10.9), while warmer colors (green to yellow) indicate weaker binding (− 6.0 to − 7.5). The distribution shows that most compounds cluster around moderate binding scores (− 7.5 to − 8.5), with a few highly potent compounds—such as those near compound numbers 12, 41, 61, and 101—displaying the strongest affinities (deep blue regions). The heatmap effectively highlights both the variability and concentration of strong binders among the tested metabolites. The compound number code, along with their corresponding name, 2D structures, PubChem ID, and binding scores, are given in the supplementary file (Table 1S).

Docking protocol validation

The superimposition of the native ligand (green) and the redocked ligand (red) revealed a high degree of spatial overlap, with a calculated RMSD value of 1.86 Å (Figs. 3D and 4D). This RMSD value falls within the acceptable threshold (< 2.0 Å), confirming that the docking procedure was capable of accurately reproducing the experimentally observed binding orientation. The redocked ligand maintained key hydrogen bond interactions with Gly18, Gly19, Gly104, Gly105, and Thr106, similar to those observed in the crystal structure, demonstrating consistency in the recognition of critical residues within the GDP-binding pocket. These results validated the accuracy of the docking workflow and ensured that the subsequent docking analyses of marine fungal metabolites were performed using a reliable and reproducible computational model.

MD simulation analysis

RMSD and RMSF

To evaluate the dynamic stability and conformational behavior of the docked complexes, a 200 ns MD simulation was performed using the Desmond package (Schrödinger Release 2023-4). The RMSD, RMSF, and torsional analyses were carried out to assess the overall stability, flexibility, and conformational adaptability of the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex throughout the simulation period.

The RMSD trajectory plot (Fig. 5A) illustrated that the Cα atoms of the FtsZ protein maintained structural stability throughout the simulation, with fluctuations remaining below 2.0 Å, indicating that no major conformational drift occurred. The ligand RMSD, representing the positional deviation of Xanalteric acid II within the active site, was persistently within the range (< 2Å) for the first 90 ns. However, it deviated after 90 ns, reaching 4.0 Å. A major rise in RMSD around 120 ns indicated transient rearrangement of surface residues, which re-equilibrated thereafter, confirming the complex’s thermodynamic stability.

The RMSF plot (Fig. 5B) provided insights into the residue-level flexibility of the FtsZ protein. The majority of the residues exhibited RMSF values below 2.0 Å, suggesting minimal backbone fluctuations. Slightly higher fluctuations were observed in loop regions near residues 50–60 and 150–160, which correspond to flexible domains involved in ligand accommodation. The low RMSF values in the catalytic pocket, especially around residues Gly18, Gly19, Thr106, and Arg140, indicated the structural rigidity and stable ligand anchoring in the active site. Ligand-specific flexibility was analyzed through the RMSF of Xanalteric acid II atoms (Fig. 5C). The ligand atoms showed fluctuations below 1.5 Å, indicating minimal internal torsional strain and conformational stability during the entire trajectory. This stable pattern reflected strong van der Waals and hydrogen bonding interactions with key residues, supporting the docking predictions. The torsional angle distribution plots (Fig. 5D) confirmed that the ligand maintained consistent conformational orientations within the active site. The restricted rotational freedom of specific bonds indicated the existence of energetically favorable orientations, further reinforcing the stable binding of Xanalteric acid II throughout the simulation.

(A) RMSD plot of the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex showing structural stability throughout the 200 ns simulation. (B) RMSF of the FtsZ residues depicting minimal backbone flexibility around the catalytic region. (C) RMSF of Xanalteric acid II atoms indicating low internal fluctuations and conformational rigidity. (D) Torsional angle distribution plots demonstrating stable rotational conformations of the ligand during simulation.

Structural stability analysis

To further validate the dynamic behavior and binding strength of the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex, additional trajectory analyses were performed, including Rg, hydrogen bond occupancy, SASA, MolSA, and PSA (Fig. 6). The average RMSD of the ligand was approximately 0.8 Å, confirming that the compound remained firmly anchored in the active site. The absence of sharp deviations indicated strong conformational restraint and high binding stability of Xanalteric acid II within the catalytic pocket. The Rg, which describes the compactness of the protein structure, exhibited negligible variation during the simulation, maintaining an average value of 3.60–3.75 Å. The minimal deviation in Rg suggested that no major unfolding or expansion occurred in the protein structure, reflecting its conformational stability in complex with Xanalteric acid II. Analysis of IntraHB revealed the presence of one to two consistent hydrogen bonds maintained throughout the trajectory. The persistence of these bonds reinforced the structural stability of the protein–ligand interface and contributed to the observed rigidity of the complex. The MolSA fluctuated narrowly between 284 and 292 Ų, suggesting limited conformational rearrangement during the simulation. Similarly, the SASA displayed a stable pattern ranging from 100 to 150 Ų, indicating that the protein retained its native folding and that no significant solvent exposure occurred in the binding cavity. The PSA remained steady at approximately 250 Ų, consistent with a balanced hydrophobic–hydrophilic interaction profile within the ligand-binding region.

Protein–Ligand contact analysis

To gain deeper insight into the molecular interactions stabilizing the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex, a comprehensive protein–ligand contact analysis was performed over the 200 ns simulation trajectory (Fig. 6). The two-dimensional interaction map (Fig. 7A) revealed that Xanalteric acid II established multiple stable hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions within the GDP-binding pocket of the FtsZ protein. The compound formed strong hydrogen bonds with Gly9, Gly19, Arg140, and Thr130, which persisted throughout the trajectory, indicating their key role in anchoring the ligand. Hydrophobic and π–π stacking interactions were observed with Phe133, Phe180, and Ala183, enhancing van der Waals stability and contributing to optimal ligand fitting within the hydrophobic subpocket.

The interaction fraction diagram (Fig. 7B) showed that Arg140, Asp184, Glu 102, and Glu136 exhibited the highest contact persistence, maintaining interaction fractions above 0.6 for the majority of the simulation time. This consistent interaction profile reflected the strong electrostatic and hydrogen bonding network that stabilized the ligand within the catalytic groove. Other residues, such as Gly101, Gly69, and Thr130 showed intermittent interactions, likely contributing to dynamic adaptation during the simulation. The contact timeline plot (Fig. 7C) demonstrated that Xanalteric acid II maintained an average of 8–10 simultaneous contacts throughout the 200 ns trajectory, with key interactions persisting beyond 150 ns, confirming its long-term stability within the FtsZ active site. The high contact occupancy with residues involved in GDP binding suggested that Xanalteric acid II may effectively disrupt FtsZ polymerization by competitively binding at the catalytic site.

Protein–ligand contact analysis of the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex during 200 ns MD simulation: (A) 2D interaction diagram illustrating hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, and water-mediated contacts with residues Arg140, Glu136, Asp184, Thr130, and Phe180. (B) Interaction fraction plot showing contact persistence, where Arg140, Asp184, and Glu136 exhibited the highest occupancy. (C) Contact timeline plot displaying the stability and frequency of interactions over time, confirming sustained ligand engagement with the binding site.

FEL, PCA, and PDF

The PCA projection plot (Fig. 8A) displayed the distribution of MD trajectory frames along the first three principal components (PC1, PC2, and PC3), which together captured the majority of the conformational variance. The trajectory clustering toward a single region in the PCA space reflected restricted global motion and convergence to a stable equilibrium state during the simulation. This limited conformational sampling suggested that no large-scale structural rearrangements occurred within the FtsZ–ligand complex, corroborating the RMSD and Rg analyses. The 3D FEL (Fig. 8B) was generated using the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) as reaction coordinates. The FEL plot revealed two major energy basins separated by a shallow transition barrier, indicating that the complex predominantly occupied a single low-energy conformation throughout the simulation. The global minimum, represented in blue, corresponded to the most stable conformational ensemble with a free energy of approximately 14–16 kJ/mol, whereas higher energy states (red regions) indicated transient conformational fluctuations. The dominance of a single, deep energy well confirmed that the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex remained structurally stable and energetically favorable under physiological conditions. The PDF analysis (Fig. 8C) provided quantitative insight into the distribution of the principal component values. Both PC1 and PC2 exhibited unimodal and overlapping density peaks, indicating that the system explored a narrow conformational space with limited structural flexibility. The overlapping profiles of PC1 and PC2 further supported a stable and energetically favorable binding mode with minimal deviation from the native conformation.

Conformational and energy landscape analyses of the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex: (A) 3D PCA projection illustrating restricted conformational clustering, indicating limited global motion. (B) 3D FEL plot showing a deep, single global energy minimum region corresponding to a stable conformational state. (C) PDF plot displaying overlapping unimodal distributions of PC1 and PC2, confirming conformational stability and limited structural fluctuation.

Dynamic Cross-Correlation matrix (DCCM) analysis

To further investigate the internal motion and cooperative dynamics of residues in the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex, a DCCM analysis was performed using the 200 ns MD simulation trajectory (Fig. 9). The DCCM map represents the correlated (positive, red) and anti-correlated (negative, blue) motions of Cα atoms across the protein backbone. Correlated motions (values close to + 1) indicate synchronized fluctuations between residue pairs, whereas anti-correlated motions (values near − 1) represent movements in opposite directions. The DCCM results revealed that the FtsZ protein exhibited extensive positive correlations within residues forming the catalytic pocket, particularly among Gly18–Gly19, Thr106, Glu136, and Asp184 (all α-helices). These residues displayed cooperative dynamics essential for maintaining the integrity of the ligand-binding site. Strong intra-domain correlations were also observed along the diagonal axis, reflecting stable local motions within α-helices and β-sheets. Conversely, mild anti-correlated motions were observed between loop regions and terminal residues, such as those near Ala70, Ala183 (α-helices), and Gly224 (β-sheet), suggesting flexible regions that contribute to conformational adaptability during ligand binding (Fig. 2S, supplementary file). Importantly, the absence of large-scale anti-correlated clusters indicated that Xanalteric acid II binding did not induce any significant destabilization or unfolding within the protein structure.

DCCM plot representing correlated (red) and anti-correlated (blue) motions among Cα atoms of the FtsZ protein during the 200 ns MD simulation. Strongly correlated motions were observed among residues Gly18–Gly19, Thr106, and Asp184, indicating cooperative dynamics within the active site that stabilize Xanalteric acid II binding.

MM-GBSA free energy analysis

The average binding free energy (ΔG_bind) was found to be − 74.77 ± 4.95 kcal/mol, confirming the strong and energetically favorable interaction between Xanalteric acid II and the FtsZ protein. Decomposition of the total binding energy revealed that van der Waals (ΔG_bind_Vander = − 50.15 ± 4.98 kcal/mol) and lipophilic (ΔG_bind_Lipophilic = − 30.13 ± 4.99 kcal/mol) contributions were the dominant stabilizing factors, indicating that hydrophobic and nonpolar interactions played a major role in maintaining complex stability (Fig. 10). The Coulombic interaction energy (ΔG_bind_Coulomb = − 19.74 ± 5.0 kcal/mol) further contributed to electrostatic attraction. The covalent (ΔG_bind_Covalent = − 5.02 ± 2.05 kcal/mol) and hydrogen bonding (ΔG_bind_HBond = − 2.01 ± 0.97 kcal/mol) terms contributed modestly but consistently to the overall binding affinity, suggesting the importance of stable hydrogen bonds in complementing van der Waals and hydrophobic contacts. Analysis shows that van der Waals (vdW) and lipophilic interactions are the dominant favorable contributors to binding, with electrostatic (Coulomb) interactions providing a secondary contribution.

Drug likeness properties

The radar plots show that both Xanalteric acid II and Apiosporamide largely fall within established drug-likeness thresholds, though several physicochemical parameters deviate from optimal ranges (Fig. 11A and B). Xanalteric acid II exhibits greater divergence in lipophilicity- and ring-related descriptors, whereas Apiosporamide more closely aligns with molecular weight, polarity, and hydrogen-bonding limits.

Acute inhalation toxicity prediction

The applicability domain plots show that both Xanalteric acid II and Apiosporamide fall within reliable prediction space, supporting confidence in the toxicity models. Fragment contribution maps show predominantly green regions, indicating non-toxic structural features, while only minimal brown areas—representing potential toxic fragments—are observed (Fig. 12A-D). These patterns align with the organ toxicity predictions, where both compounds are classified as inactive for hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and carcinogenicity, suggesting an overall favorable toxicity profile (Table 2). The models suggest a favorable toxicity outlook for both metabolites, indicating low likelihood of major organ-specific adverse effects.

Acute inhalation toxicity prediction of Xanalteric acid II and Apiosporamide. Applicability domain (A) and predicted fragment contribution (B) of Xanalteric acid II. Applicability domain (C) and predicted fragment contribution (D) of Apiosporamide. The green color represents the fragment contribution for non-toxic properties and brown color for toxic fragment.

Discussion

TB continues to pose a major global health threat, aggravated by the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant strains of Mtb. The urgent need for new therapeutic agents with novel mechanisms of action has directed research toward unconventional sources, among which marine ecosystems have emerged as a rich repository of structurally unique bioactive metabolites. Marine-derived fungi, in particular, produce diverse secondary metabolites with remarkable pharmacological potential, including antibacterial, antifungal, and anticancer activities61,62. In this context, the present study aimed to identify and characterize potential inhibitors of the bacterial cell division protein FtsZ, a highly conserved and essential GDPase involved in bacterial cytokinesis. Inhibiting FtsZ disrupts the Z-ring assembly process, leading to cell division arrest and bacterial death, making it an attractive target for anti-TB drug development.

The docking and binding free energy results obtained in the present study for the Xanalteric acid II–FtsZ complex exhibited strong concordance with previously reported FtsZ inhibition studies42,63. In our docking analysis, Xanalteric acid II demonstrated the highest binding affinity of − 10.9 kcal/mol, forming stable hydrogen bonds with Arg140 and Thr130, two residues essential for the GDP-binding and polymerization functions of FtsZ. This binding energy was significantly higher than that of the native co-crystal ligand (− 9.1 kcal/mol) and the standard drug moxifloxacin (− 7.7 kcal/mol), indicating enhanced inhibitory potential. To contextualize the predicted binding affinity of the marine fungal metabolites, we compared our docking scores with values reported for established FtsZ inhibitors. Literature indicates that most validated FtsZ inhibitors—including benzamide derivatives and curcumin-based molecules—exhibit docking affinities in the approximate range of − 7.0 to − 10.5 kcal/mol64. Furthermore, drug repurposing study revealed Sitagliptin and Paroxetine scored − 9.4 and − 9.0 kcal/mol, respectively65.

Comparatively, Gurnani et al.. evaluated cyanobacterial metabolites against FtsZ and reported docking affinities of − 6.01 and − 6.5 kcal/mol for compounds aphanorphine and alpha-dimorphecolic acid, respectively. Among these, aphanorphine exhibited the strongest interaction, stabilized through hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic contacts within the active pocket66. Our study also revealed that hydrophobic interaction plays crucial role for binding mode to the active site which aligned with previous study67. The stronger docking affinity observed for Xanalteric acid II compared to these metabolites suggests superior complementarity with the FtsZ catalytic site. Previous studies have reported several FtsZ inhibitors with notable docking affinities. For example, ZINC000524729297 and ZINC000604405393 showed binding energies of − 8.73 kcal/mol and − 8.55 kcal/mol, respectively, supported by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions68. Another investigation identified benzimidazole derivative (P32) as a strong candidate with a docking score of − 9.6 kcal/mol69, while a larger screening effort reported ten molecules with docking scores ranging from − 9.549 to − 4.290 kcal/mol70. The structural comparison between Xanalteric acid II and previously reported FtsZ inhibitors (ZINC000524729297, ZINC000604405393, and P32) reveals several shared pharmacophoric features that may underlie their strong predicted affinities (Fig. 13). All molecules contain a polycyclic aromatic core (highlighted in blue), which is a recurrent scaffold among FtsZ inhibitors and is known to facilitate π–π stacking and hydrophobic packing within the interdomain cleft and nucleotide-adjacent pocket. Xanalteric acid II exhibits a similar fused-ring aromatic region, suggesting that it can occupy these hydrophobic subpockets in a manner analogous to the known inhibitors. Furthermore, the -OH group is important for hydrogen bonding. Additionally, both ZINC-series compounds and P32 incorporate phenolic or hydroxyl-substituted aromatic groups (red ovals), which contribute polar contacts and hydrogen bonding.

In comparison, the top marine fungal metabolites identified in our study exhibit docking affinities that fall within, and in some cases exceed, these previously reported values. Additionally, comparison with previous FtsZ inhibitor studies reveals strong agreement in the key residues contributing to ligand recognition. Prior computational and structural analyses have repeatedly identified Gly19, and Arg140 located within the catalytic pocket as critical pharmacophoric residues for inhibitor engagement71. In our study, the top marine fungal metabolites also formed recurrent interactions with Gly19 (catalytic residue) and Arg140, during docking. Arg140 frequently interacted with the screened metabolites due to its strategic position on the helix at the edge of the interdomain cleft (IDC). Its positively charged guanidinium group readily forms hydrogen bonds, electrostatic interactions, and cation–π contacts, making it a common anchoring residue for diverse ligands39. The convergence of these findings with earlier reports indicates that the predicted binding poses are consistent with established FtsZ inhibition mechanisms. This alignment supports the functional relevance of the marine-derived scaffolds and underscores their potential as credible candidates for further FtsZ-targeted drug development.

To further substantiate the docking findings, MD simulation was performed to evaluate the dynamic stability and conformational adaptability of the FtsZ–Xanalteric acid II complex under physiological conditions. The RMSD profile of the complex remained stable throughout the 200 ns simulation, fluctuating around 2.0–3.5 Å, which indicates minimal deviation from the initial docked conformation and sustained structural stability. RMSF analysis showed that the binding site residues exhibited limited flexibility confirming restricted mobility and enhanced rigidity upon ligand binding. A consistent Rg profile reflects preservation of the protein’s global compactness and suggests that Xanalteric acid II does not induce unfolding or destabilizing motions. This agrees with the RMSD results, further supporting a structurally stable protein–ligand complex. MolSA measures the van der Waals surface area of the ligand and reflects changes in its conformational spread while bound72. The relatively constant MolSA values indicated that Xanalteric acid II maintains a stable internal conformation during binding, without major structural rearrangements or steric clashes within the active site. SASA tracks the extent of ligand exposure to solvent during the simulation73. The SASA slightly decreased upon complex formation, suggesting reduced solvent exposure and improved hydrophobic packing at the binding interface, which is characteristic of a stable and energetically favorable complex. PSA reflects the polar region of the ligand surface that is accessible to solvent and is important for hydrogen bonding and desolvation energetics74. The steady PSA profile indicates that the ligand maintains a consistent pattern of polar interactions with the surrounding residues, supporting stable hydrogen-bonding networks throughout the trajectory.

PCA revealed that PC1 and PC2 capture the principal fluctuations of the complex, dominated by motions in the interdomain cleft and catalytic loops. The tight clustering of trajectory points indicates limited conformational drift and supports a stable binding state. FEL analysis further showed a single deep free-energy minimum, reflecting a dominant, energetically favorable conformation. The lack of multiple minima suggests that ligand binding restricts large-scale motions and maintains structural stability throughout the simulation. The binding free energy computed through MM/GBSA analysis provided quantitative support to the observed stability. The total binding free energy (ΔG_bind) was − 74.77 kcal/mol, indicating a strong and favorable interaction. Among the contributing energy components, van der Waals and lipophilic terms were predominant, while Coulombic and hydrogen bonding interactions further strengthened the binding. The energetic contribution from hydrophobic and polar forces emphasizes the compound’s balanced interaction profile, which is essential for both stability and specificity.

Together, the stable RMSD patterns and preserved binding pose corroborate the strong ΔG_bind value obtained from MM/GBSA calculation, confirming that the favorable energy components arise from a physically stable and well-maintained protein–ligand complex. Both compounds exhibit acceptable physicochemical profiles and predominantly non-toxic fragment contributions, with minimal toxic alerts. Combined with inactive organ-toxicity predictions, these findings suggest favorable safety and drug-likeness, supporting their potential for further pharmacological development. These findings not only highlight the therapeutic promise of marine-derived compounds but also underscore the importance of exploring oceanic biodiversity for discovering next-generation anti-TB agents that can overcome the growing challenge of drug resistance.

Limitation

Docking and MM/GBSA provide useful preliminary insights but have inherent limitations. Docking scores simplify the binding landscape and overlook entropy, solvation, and protein flexibility, while MM/GBSA relies on approximate solvation models, making ΔG_bind values qualitative rather than absolute. These results therefore serve mainly as relative rankings, not definitive measures of affinity. Another limitation is that DCCM analysis, although informative, would benefit from a more detailed integration with specific structural regions (loops, helices, and β-sheets) to fully contextualize correlated motions. Ultimately, experimental validation is required to confirm the inhibitory potential of the identified metabolites.

Conclusion

The present study elucidates the molecular interaction mechanism of marine fungal metabolites against the FtsZ protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Xanalteric acid II emerged as the most potent inhibitor, exhibiting higher binding affinity, strong intermolecular interactions, and dynamic stability compared to standard drugs. The stable RMSD, compact Rg, and favorable MM/GBSA energy profile support its strong affinity toward the FtsZ catalytic site. Conformational analyses, including PCA, FEL, and DCCM, further confirmed the energetic and structural stability of the complex. These findings collectively suggest that marine-derived metabolites, especially Xanalteric acid II, could serve as promising lead scaffolds for the rational design of next-generation anti-TB agents targeting the FtsZ protein.

Data availability

Data will be provided from the corresponding author on request.

References

Cazzaniga, G. et al. Natural products against key Mycobacterium tuberculosis enzymatic targets: emerging opportunities for drug discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 224, 113732 (2021).

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Geneva: WHO. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Glob. Tuberc. Rep. 68 (2024). (2024).

Goletti, D., Meintjes, G., Andrade, B. B., Zumla, A. & Shan Lee, S. Insights from the 2024 WHO global tuberculosis Report – More comprehensive Action, Innovation, and investments required for achieving WHO end TB goals. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 150, 107325 (2025).

Singh, R., Kumar, S., Bhardwaj, V. K. & Purohit, R. Screening and reckoning of potential therapeutic agents against DprE1 protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Mol. Liq. 358, 119101 (2022).

Ioerger, T. R. et al. Identification of new drug targets and resistance mechanisms in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 8, 1–13 (2013).

Mi, J., Gong, W. & Wu, X. Advances in Key Drug Target Identification and New Drug Development for Tuberculosis. Biomed Res. Int. 1–23 (2022).

Mdluli, K. & Spigelman, M. Novel targets for tuberculosis drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6, 459–467 (2006).

Huang, Q. et al. Targeting FtsZ for antituberculosis drug discovery: noncytotoxic taxanes as novel antituberculosis agents. J. Med. Chem. 49, 463–466 (2006).

Akinpelu, O. I., Lawal, M. M., Kumalo, H. M. & Mhlongo, N. N. Drug repurposing: fusidic acid as a potential inhibitor of M. tuberculosis FtsZ polymerization – Insight from DFT calculations, molecular Docking and molecular dynamics simulations. Tuberculosis 121, 101920 (2020).

Rahman, M., Wang, P., Wang, N. & Chen, Y. A key bacterial cytoskeletal cell division protein FtsZ as a novel therapeutic antibacterial drug target. BJBMS 20, 310–318 (2020).

Huang, Q., Tonge, P. J., Slayden, R. A., Kirikae, T. & Ojima, I. FtsZ: A novel target for tuberculosis drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 7, 527–543 (2007).

Zhang, H., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Qiao, L. Identification of anti- Mycobacterium tuberculosis agents targeting the interaction of bacterial division proteins FtsZ and SepFe. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 13, 2056–2070 (2023).

Kumar, K. et al. Discovery of anti-TB agents that target the cell-division protein FtsZ. Future Med. Chem. 2, 1305–1323 (2010).

Singh, R., Manna, S., Nandanwar, H. & Purohit, R. Bioactives from medicinal herb against bedaquiline resistant tuberculosis: removing the dark clouds from the horizon. Microbes Infect. 26, 105279 (2024).

Patel, S. et al. Diversity of secondary metabolites from marine streptomyces with potential anti-tubercular activity: a review. Arch. Microbiol. 207, 64 (2025).

Peng, X., Zeng, Z., Hassan, S. & Xue, Y. The potential of marine natural products: recent advances in the discovery of Anti-Tuberculosis agents. Bioorg. Chem. 151, 107699 (2024).

Daletos, G., Ancheeva, E., Chaidir, C., Kalscheuer, R. & Proksch, P. Antimycobacterial metabolites from marine invertebrates. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim). 349, 763–773 (2016).

Hafez Ghoran, S., Taktaz, F., Ayatollahi, S. A. & Kijjoa, A. Anthraquinones and their analogues from Marine-Derived fungi: chemistry and biological activities. Marine Drugs 20, 1-69 (2022).

Tapfuma, K. I. et al. Antimycobacterial activity and molecular Docking of methanolic extracts and compounds of marine fungi from Saldanha and false Bays, South Africa. Heliyon 8, e12406 (2022).

Villanueva-Silva, R. et al. Chemical diversity and antimicrobial potential of cultivable fungi from deep-sea sediments of the Gulf of Mexico. Molecules 26, 1–16 (2021).

Aghajani, J. & Farnia, P. Molecular dynamic simulations and molecular Docking as a potential way for designed new inhibitor drug without resistance. Tanaffos 21, 1–14 (2022).

Kamaria, P. et al. Evaluation of Quercus infectoria phytoconstituents against oral cancer: network Pharmacology, Docking Simulation, and in vitro cytotoxicity assay. Food Sci. Nutr. 13, 1–23 (2025).

Lyu, C. et al. CMNPD: A comprehensive marine natural products database towards facilitating drug discovery from the ocean. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D509–D515 (2021).

Chandrasekhar, V. et al. COCONUT 2. 0 : a comprehensive overhaul and curation of the collection of open natural products database. Nucleic Acids Res. 53, 634–643 (2025).

Shabbir, F. et al. Computer-aided screening of marine fungal metabolites as potential inhibitors of new Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–24 (2025).

Mousa, W. K. & Raizada, M. N. The diversity of anti-microbial secondary metabolites produced by fungal endophytes: an interdisciplinary perspective. Front. Microbiol. 4, 1–18 (2013).

He, K. Y. et al. New chlorinated Xanthone and anthraquinone produced by a mangrove-derived fungus penicillium citrinum HL-5126. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 70, 823–827 (2017).

Li, X. D., Li, X. M., Yin, X. L., Li, X. & Wang, B. G. Antimicrobial sesquiterpenoid derivatives and monoterpenoids from the deep-sea sediment-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor SD-330. Mar. Drugs. 17, 1–12 (2019).

Yang, K. L. et al. Antibacterial anthraquinone derivatives from a sea anemone-derived fungus Nigrospora Sp. J. Nat. Prod. 75, 935–941 (2012).

Hung, P. N. et al. Dehydroxychlorofusarielin B, an antibacterial polyoxygenated decalin derivative from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus Sp. J. Nat. Prod. 70, 1188–1190 (2007).

Guo, W. et al. Antibacterial polyketides from the Deep-Sea-Derived fungus penicillium sp. F23-2. J. Nat. Prod. 78, 2699–2703 (2015).

Khamthong, N., Rukachaisirikul, V., Phongpaichit, S., Preedanon, S. & Sakayaroj, J. An antibacterial cytochalasin derivative from the marine-derived fungus diaporthaceae sp. PSU-SP2/4. Phytochem Lett. 10, 5–9 (2014).

Li, Y. H. et al. Antibacterial alkaloids and polyketide derivatives from the deep Sea-Derived fungus penicillium cyclopium SD-413. Mar. Drugs. 18, 5–12 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Cytotoxic and antibacterial compounds from the coral-derived fungus Aspergillus tritici SP2-8-1. Mar. Drugs. 15, 1–10 (2017).

Yu, G. et al. Cytotoxic tetrahydroxanthone dimers from the mangrove-associated fungus Aspergillus versicolor HDN1009. Mar. Drugs 16, 1–8 (2018).

Thapa, S., Biradar, M. S., Banerjee, J. & Karati, D. In-silico approach for predicting the inhibitory effect of home remedies on severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 In-silico approach for predicting the inhibitory effect of home remedies on severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2. Makar J. Sci 27, 194–207 (2023).

Sonnenkalb, L., Trubenová, B., Regoes, R. R., Merker, M. & Niemann, S. The mutant selection window of Moxifloxacin and bedaquiline resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Infect. 91, 106523 (2025).

Shilpi, J. A. et al. Molecular Docking studies on InhA, MabA and PanK enzymes from Mycobacterium tuberculosis of ellagic acid derivatives from Ludwigia adscendens and Trewia nudiflora. Silico Pharmacol. 3, 1–7 (2015).

Leung, A. K. W. et al. Structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis FtsZ reveals Unexpected, G Protein-like conformational switches. J. Mol. Biol. 342, 953–970 (2004).

Kurmi, S. P. C., Thapa, S. & Karati, D. Molecular Docking and Pharmacokinetic evaluations of curcumin-based scaffolds as MDM2-p53 inhibitors. Discov Chem. 2, 53 (2025).

Shao, Q. & Zhu, W. Assessing AMBER force fields for protein folding in an implicit solvent. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20, 7206–7216 (2018).

Thapa, S., Nargund, S. L. & Biradar, M. S. Molecular Design and In-Silico Analysis of Trisubstituted Benzimidazole Derivatives as Ftsz Inhibitor. J. Chem. 1–9 (2023). (2023).

Pandey, B. et al. LC-MS profiling and cytotoxic activity of angiopteris Helferiana against HepG2 cell line: molecular insight to investigate anticancer agent. PLoS One. 19, 1–24 (2024).

Laskowski R A, MacArthur M W, Moss D S, Thornton J M. PROCHECK - a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. App. Cryst. 26, 283–291 (1993).

Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., F Tillack, A. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new Docking Methods, expanded force Field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 61, 3891–3898 (2021).

Bhojwani, H. R. & Joshi, U. J. Pharmacophore and Docking guided virtual screening study for discovery of type I inhibitors of VEGFR-2 kinase. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 13, 186–207 (2017).

Thapa, S., Nargund, S. L., Biradar, M. S., Banerjee, J. & Karati, D. In-silico investigation and drug likeliness studies of benzimidazole congeners: the new face of innovation. Inf. Med. Unlocked. 38, 1–11 (2023).

Id, M. A. A. I. et al. Benzothiazinone analogs as Anti- Mycobacterium tuberculosis DprE1 irreversible inhibitors: covalent docking, validation, and molecular dynamics simulations. PosOne 19, 1–24 (2024).

Thapa, S. et al. LC-MS profiling and multi-target mechanistic insights of hibiscus rosa-sinensis in diabetes: network pharmacology, molecular docking, MD simulation, PCA, and in-vitro α-amylase Inhibition. Pharmacol. Res. - Mod. Chin. Med. 16, 100636 (2025).

Zala, A. R. et al. Molecular modeling and biological investigation of novel s-triazine linked benzothiazole and coumarin hybrids as antimicrobial and antimycobacterial agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 0, 1–12 (2023).

H S, Y. et al. Polyphenol-based therapeutics for glioblastoma: validation from In-vitro cell viability assay and integrated onco-omics computational analysis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-025-04690-y

Kumar, R. et al. Molecular docking, drug – likeness properties, and toxicity prediction of alkaloidal phytoconstituents of Piper longum against monoamine oxidase enzyme – A as an anti – depressive agent. Discov Chem. 2, 1–18 (2025).

Kiran, S. et al. Integrated computational approach revealed the potential inhibitory effect of Xanthone derivatives against Marburg virus nucleocapsid. VirusDisease 3, 415–427 (2025).

Kushwaha, P. P. et al. Identification of natural inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 drugable targets using molecular Docking, molecular dynamics Simulation, and MM-PBSA approach. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 11, 1–17 (2021).

Alotaibi, B. S. In Silico identification of phytochemical inhibitors for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis based on novel pharmacophore generation and molecular dynamics simulation studies. BMC Chem. 18, 1–12 (2024).

Ali, I. et al. Identification of natural lead compounds against Hemagglutinin-Esterase surface glycoprotein in human coronaviruses investigated via MD Simulation, principal component Analysis, Cross-Correlation, H-Bond plot and MMGBSA. Biomedicines 11, 1–17 (2023).

C, P. et al. Repurposing terfenadine and Domperidone for Inhibition of apoptotic gene association in colorectal cancer: A system Pharmacology approach integrated with molecular docking, MD simulations, and post-MD simulation analysis. Bioinform Biol. Insights. 19, 1–21 (2025).

Fu, L. et al. ADMETlab 3.0: an updated comprehensive online ADMET prediction platform enhanced with broader coverage, improved performance, API functionality and decision support. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W422–W431 (2024).

Borba, J. V. B., Alves, V. M. & Braga, R. C. STopTox: an in Silico alternative to animal testing for acute systemic and topical toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect. 130, 1–12 (2022).

Banerjee, P., Kemmler, E., Dunkel, M. & Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W513–W520 (2024).

Azhari, M., Merliani, N., Singgih, M., Arai, M. & Julianti, E. Insights into natural products from Marine-Derived fungi with antimycobacterial properties: opportunities and challenges. Mar. Drugs. 23, 1–49 (2025).

Fu, J. et al. Marine-Fungi-Derived gliotoxin promotes autophagy to suppress mycobacteria tuberculosis infection in macrophage. Mar. Drugs. 21, 1–14 (2023).

Bharti, R., Mishra, S. & Pandey, A. Identification of natural FtsZ inhibitors through computational approaches to combat drug-resistant tuberculosis. Results Chem. 16, 102354 (2025).

Tripathy, S. & Sahu, S. K. FtsZ inhibitors as a new genera of antibacterial agents. Bioorg. Chem. 91, 103169 (2019).

Tovar-Nieto, A. M. et al. The repurposing of FDA-Approved drugs as FtsZ inhibitors against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: an in Silico and in vitro study. Microorganisms 12, 1–13 (2024).

Gurnani, M. et al. Inhibition of filamentous thermosensitive Mutant-Z protein in Bacillus subtilis by cyanobacterial bioactive compounds. Molecules 27, 1–21 (2022).

Sciò, P. et al. Identification of a new FtsZ inhibitor by virtual Screening, mechanistic Insights, and Structure-Activity relationship analyses. ACS Infect. Dis. 11, 998–1007 (2025).

Roy, A. & Anbarasu, A. Unveiling Berberine analogues as potential inhibitors of Escherichia coli FtsZ through machine learning molecular Docking and molecular dynamics approach. Sci. Rep. 15, 1–18 (2025).

Sonwane, P. N. & Kumbhare, M. R. Molecular Docking and pharmacokinetics of benzimidazole-based FtsZ inhibitors for tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 15, 35270 (2025).

Vemula, D., Maddi, D. R. & Bhandari, V. Homology modeling, virtual screening, molecular docking, and dynamics studies for discovering Staphylococcus epidermidis FtsZ inhibitors. Front. Mol. Biosci. 10, 1–24 (2023).

Thapa, S., Nargund, S. L., Biradar, M. S., Banerjee, J. & Karati, D. In-silico investigation and drug likeliness studies of benzimidazole congeners: the new face of innovation. Inf. Med. Unlocked. 38, 101213 (2023).

Saha, S. et al. Molecular dynamics Simulation, and quantum mechanics calculation based phytochemical screening of Croton Bonplandianum against breast cancer by targeting Estrogen Receptor-α (ERα). Appl. Sci. 14, 1–22 (2024). Pharmacoinformatics.

Abchir, O. et al. Exploration of cannabis constituents as potential candidates against diabetes mellitus disease using molecular docking, dynamics simulations and ADMET investigations. Sci. Afr. 21, e01745 (2023).

Aghahosseini, F., Bayat, M., Sadeghian, Z., Gheidari, D. & Safari, F. Synthesis, molecular Docking study, MD simulation, ADMET, and drug likeness of new thiazolo[3,2-a]pyridine-6,8-dicarbonitrile derivatives as potential anti-diabetic agents. PLoS One. 19, 1–19 (2024).

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia [Grant No. KFU254761].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Meghana S R: Conceptualization, Software, Methodology, Resources, Investigation. Yogesh H S: Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Formal analysis. Anitha KN: Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. Sibghatullah Muhammad Ali Sangi: Writing - Review & Editing. Sadik Shaik: Formal analysis, Resources. Sreeharsha Nagaraja: Formal analysis, Data Curation. Girish Meravanige: Formal analysis, Data Curation. Monirul Islam: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation. Pavan Kumar Sreenivasalu: Investigation, Validation. Rashed M. Almuqbil: Formal analysis, Data Curation. Shahzad Chohan: Formal analysis, Data Curation. Bipindra Pandey: Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation. Shankar Thapa: Conceptualization, Software, Methodology, Resources, Investigation. Ayomide Victor Atoki: Resources.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

S R, M., H S, Y., Sangi, S.M.A. et al. In-silico screening of marine fungal metabolites identifies potential FtsZ inhibitors against MDR-tuberculosis through docking and molecular dynamics analysis. Sci Rep 16, 4030 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34116-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34116-x