Abstract

The thermal-hydro-mechanical (THM) coupling and a strong mining disturbance environment all have a significant impact on deep ground engineering excavations, which increases the risk of a rock burst disaster. The independently developed THM multi-physics coupling apparatus enables replication of intricate geological conditions in engineered rock formations, with high-strain-rate compression experiments on deep-buried rock specimens being implemented through a split Hopkinson pressure bar testing platform. The fracture surface microstructure and the pore structure of the rock after impact are characterized by SEM and NMR. Results show that the dynamic stress–strain curve exhibits nonlinear behavior, accompanied by a significant 'plastic platform area.' Under the same temperature and pre-static stress, the energy time-history evolution distribution of rock in the process of dynamic compression has the characteristics of synchronous and different amplitudes. The energy reflection coefficient and energy dissipation coefficient obey a good exponential function and a Gaussian function relationship with water pressure, respectively. 'Compression-shear crushing failure → inclined shear boundary failure → fracture failure’ is the development trend of the overall failure mode of rock when temperature and water pressure increase. The dynamic damage threshold is between 0.35 and 0.36. Microscopically, it shows a transformation trend of intergranular fracture, complex fracture, and transgranular fracture. NMR analysis reveals that elevated water pressure enhances the structural integrity of rock pores, accompanied by a reduction in pore dimensions and a progressive decline in overall porosity. A mechanical model of sliding microcrack propagation under THM coupling and impact load is constructed. By analyzing the variation patterns of crack initiation points under different operating conditions, the accuracy and adaptability of this model were validated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

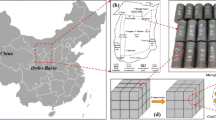

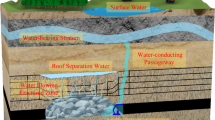

Mineral resource development will eventually reach depths of kilometers due to the depletion of shallow resources. After the mineral resources enter the depth of kilometers, the difficulty of mining will increase, and the dynamic disasters and safety accidents, such as high-level rockbursts and mine earthquakes, large-scale coal and gas explosions, and water inrush, will be more frequent and hidden1,2. Compared with the exploitation of shallow resources, the environment faced by deep mining is more complicated, the mechanism is unclear, and it is difficult to predict and effectively control3,4. First of all, strong disturbance loads brought on by blasting, excavation, and extensive subsurface engineering rock mass mining are unavoidable. Secondly, the deep rock mass is subjected to high in-situ stress, which mainly comes from the tectonic stress generated by geological structure and the large vertical stress generated by the self-weight of overlying strata. At the same time, the deep underground is prone to producing great karst water pressure. As the rise of mining depth, the ground temperature under deep conditions will be higher and higher. The extraction of deep-seated coal deposits encounters challenging geological conditions, including elevated thermal gradients, heightened karst aquifer pressures, substantial crustal stresses, and intense operational disturbances during mining activities5,6(Fig. 1). Due to the unique environment of deep rock masses characterised by ‘three high levels and one strong disturbance’, the mechanical behavior is often different from the normal state. Under the influence of intense dynamic load disturbances like tunnel blasting, the deep roadway is more likely to become unstable and fail than the shallow roadway7,8. The deep dynamic disaster of the coal mine is the result of multi-field coupling. Several major disasters in deep mining are interrelated, interdependent, and mutually restricted, which pose serious challenges to deep underground coal mining9,10. The absence of comprehensive research on the dynamic mechanical characteristics of deep rock bulk with thermal-hydro-mechanical under strong disturbance loads, such as blasting excavation, has become an important technical problem. To establish a theoretical basis for stability assessment in deep underground rock engineering, this study investigates the dynamic behavior of deep rock masses under thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling effects. Furthermore, it elucidates the evolutionary patterns of multi-physical field interactions within deep geological formations subjected to intense external disturbances.

In the challenging conditions of deep underground rock engineering, substantial research has focused on analyzing how combined thermal, hydraulic, and mechanical factors influence rock behavior. Studies have particularly examined thermo-mechanical interactions, hydraulic-stress couplings, and multi-field interactions involving temperature, fluid pressure, and mechanical stresses to understand their impacts on rock behavior and mechanical characteristics11,12. Many previous studies have suggested that the rising temperatures will cause rock minerals to expand thermally, which will lead to thermal cracks and a reduction in the mechanical strength13,14. The mechanical properties and physical behavior of different rock types exhibit significant variations under temperature fluctuations, primarily attributed to differences in their mineral composition and microstructure15. Moreover, the mechanical characteristics of the rock sample will generally decrease as its water content and soaking period increase16,17. In the process of triaxial loading, the stress–strain curve of deep granite under high stress and high water pressure coupling environment shows obvious brittle characteristics, with a long yield stage and high residual strength18; under T-M coupling state, the porosity and fractal dimension of sandstone decrease with the rise of temperature, while the permeability decreases first and then increases19; Under coupled thermal–hydraulic-mechanical conditions, deep sandstone demonstrates enhanced peak stress and dynamic strain when exposed to elevated temperatures (20 °C ~ 50 °C) and controlled confining pressure20, However, its elastic modulus initially increases but subsequently declines with rising temperature and pore water pressure. A critical thermal fracturing threshold exists between 25 °C ~ 100 °C, where strength degradation arises from combined effects of thermal fracturing, pore water pressure effects, and high-temperature water–rock interactions21. Existing research predominantly focuses on analyzing how temperature-seepage pressure-stress interactions affect rock mechanical behavior under static loading conditions. However, investigations into the dynamic mechanical responses and failure mechanisms of deep rock formations under coupled multi-field environmental effects remain insufficiently explored.

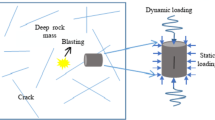

At present, to simulate the strong disturbance environment caused by blasting excavation and large-scale mining of deep rock mass, the commonly used devices in laboratory experiments are mainly the plate impact test device, SHPB, and drop hammer test device22,23. Because of the advantages of good controllability, strong practicability, and convenient operation, SHPB has gradually become a common experimental equipment for scholars at home and abroad to measure the dynamic mechanical response features of deep rock24. Dynamic impact tests of red sandstone under different hydraulic pressure and ground stress conditions were conducted by Jin et al.25, who also designed a SHPB test apparatus for high hydraulic pressure and ground stress rock. Wu et al.[26]selected porous green sandstone for SHPB impact test under water-force coupling and derived a dynamic constitutive model of deep sandstone considering water-force coupling factors. Based on the SHPB device, Wang et al.27 designed a set of water pressure loading test systems, and used the system to examine the dynamic impact coal samples’ test under water pressure and static axial prestress loading environments. It is concluded that impact and high axial static load are two adverse conditions that get coals rock more easily damaged. Conversely, the existence of water pressure has a positive effect on the coal, which can enhance the dynamic compressive strength. Zhao et al.[28]used the self-developed fluid–solid coupling SHPB loading system to test the deep sandstone. The findings demonstrate that as the impact rate and confining pressure increase, so does the sample’s dynamic compressive strength, the impact rate has a significant impact on the cohesiveness. The above research only considers the influence of H-M coupling on the dynamic mechanical response features of rock. But in addition to causing the dynamic mechanical features of engineering rock mass to deteriorate, rising deep subsurface temperatures will also alter ground stress29, which could significantly affect the dynamic mechanical properties. The impact of thermal-hydro-mechanical coupling on the dynamic mechanical feature of rock, however, is poorly understood. According to studies, a moderate increase in temperature will significantly alter the way that rock mechanical properties deteriorate and how microcracks propagate30,31. Additionally, the effect of temperature on the dynamic mechanical features of rock under temperature-water pressure-stress (THM) coupling conditions will be more complex. Consequently, it is limited to researching the effect of H-M or T-M coupling on the dynamic mechanical features of rock. Owing to the absence of multi-field coupled rock dynamics testing apparatus and varied experimental design priorities across research domains, the dynamic mechanical response patterns, fracture mechanism evolution, energy dissipation processes, and microstructural damage characteristics of rocks in high-temperature, high-seepage pressure, and high-stress coupled environments remain incompletely characterized, revealing a lack of systematic understanding in current research. In particular, the deep rock’s damage and energy dissipation under dynamic load are also the focus of relevant power engineering in deep coal mining32,33. For example, the key to the design of the blasting scheme is how to improve the energy utilization rate of explosives, reduce the rock breaking rate, and control the damage of the surrounding rock in the near area of blasting. Therefore, it can be known that the rational allocation of rock energy distribution and transformation under dynamic load impact and the precision control of damage state are of considerable importance for ensuring the efficient mining of coal mines. Therefore, it is crucial to further consider the introduction of temperature field, truly restore the multi-field coupling state of 'three high and one disturbance’, and carry out study on the dynamic mechanical features and deformation and failure modes under the action of T-H-M coupling at the same time, to clarify the dynamic energy dissipation characteristics and structural damage characteristics of deep rock mass, and reduce rock burst disasters. Combined with damage mechanics and fracture mechanics, the relevant dynamic physical and mechanical models of THM coupling are improved.

This paper aims to understand the damage characteristics and dynamic energy change features of deep rock under the influence of THM interaction. The self-developed THM multi-field environment coupling SHPB test device is used to simulate the complex environment of engineering rock. The dynamic impact compression test is performed on the saturated sandstone as the test object in a thermal-hydro-mechanical multi-field environment. The dynamic stress–strain curve, energy evolution parameters are studied with temperature (33 °C ~ 57 °C) and water pressure (2 MPa ~ 14 MPa); The microstructure of rock fracture surface was analyzed by an electronic digital microscope, and the microstructure of fracture surface and pore structure of rock after impact were characterized by SEM and NMR. By constructing an improved slip-type micro-crack propagation mechanical model, the propagation mechanism between cracks in rock under THM coupling and impact load is explored. Through the research of this paper, it is anticipated to offer a theoretical foundation and significant point of reference for the advancement of deep engineering in the intricate geological setting of "three high and one disturbance."

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

With the average burial depth of 825 m, the test rock sample was extracted from a deep coal mine sandstone in Huainan City, Anhui Province, China. All samples come from the same homogeneous sandstone to guarantee the sample’s integrity and homogeneity, and Table 1 displays the sample’s mechanical and physical parameters. Based on the standard of the ISRM34 and the Chinese rock dynamic characteristics test procedure35, the thickness H = 25 mm and the outer length D = 50 mm of the sample, and the flatness error of the two ends is ± 0.05 mm, the complete standard rock sample is selected and placed in the vacuum saturation device. When the vacuum reaches −0.1 MPa, it is allowed to stand for 48 h to ensure complete saturation. The preparation process of the sandstone are illustrated in Fig. 2.

The mineral composition analysis and microscopic morphology observation of sandstone samples after vacuum saturation treatment were carried out by Smartlab SE X-ray diffractometer and FlexSEM 1000 SEM scanning electron microscope. Fig. 3 diaplays the XRD diffraction pattern of the samples and analyzed by XRD technology. Sample is mostly maded from quartz, potassium feldspar, hematite, plagioclase, kaolinite, and a trace quantity of clay minerals. Fig. 4 displays the rock sample’s interior SEM microstructure. It can be obtained that the internal microstructure is dense, and there is no obvious natural crack.

SHPB test device

The test is conducted using the self-developed THM multi-field coupling SHPB device, and it is composed of an impact dynamic loading system, data processing system, temperature-water pressure (T-H) loading system, and axial static stress loading system. Fig. 5 dispalys the schematic diagram of the test device. The innovation of the device is to add a temperature-water pressure loading device and an axial static stress device to the traditional SHPB device. The temperature-water pressure loading device is associated with the high and low temperature water bath circulation box. The water medium around the deep rock is heated to the target temperature by water bath heating, so as to achieve the purpose of simulating the real geothermal environment. The water bath heating box can display the heating temperature in real time, and the water bath heating temperature range is between 0 ~ 100 °C.On the intelligent control system of axial (ring) pressure, the display controller can output oil pressure to the axial static stress loading device by controlling the oil cylinder and the hydraulic line to generate stress load, to provide high static stress to deep rock, and adjust the stress load to ensure accuracy. The stress value range is 0 ~ 40 MPa, and the axial static stress continuous maintenance function is realized during the impact process, and the display controller displays the positive axial pressure. The strong disturbance load is realized by the impact dynamic loading system, which mainly includes a frequency conversion air pressure device, an incident bar, a high-pressure cylinder, a transmission bar, an impact bar, and a laser velocimeter. The data processing system is composed of a computer, oscilloscope, and dynamic resistance strain gauge, which is in charge of processing and keeping track of the reflected, transmitted, and incident waves that the strain gauge collects.

The self-developed temperature-water pressure loading device includes a water outlet pipe, water inlet pipe, water stop valve, water pressure display, sealing cover, water stop cover, confining pressure actuator, and bearing bar. The physical diagram of the THM multi-field coupled Hopkinson pressure bar device and temperature-water pressure loading device is shown in Figs.6a and b. The main principle of water pressure device is as follows: there is heated water medium and no bubbles appear within the device, the water stop valves at the inlet and outlet are closed, the axial (ring) pressure intelligent control system controls the oil cylinder to output oil pressure to the confining pressure actuator through the hydraulic line, and adjusts the expansion amount of the bearing bar, so that the internal volume changes, so that the water pressure can be adjusted. The water pressure range is 0 ~ 25 MPa, the steady-state control accuracy is ± 1 MPa, the loading rate is controllable. The strong disturbance impact load and the axial prestress are transmitted to the deep rock through the transmission bar and the incident bar, respectively. Simultaneously, the deep rock is affected by the water pressure and temperature inside the temperature-water pressure loading device. The loading conditions of the sample are presented in Fig. 6c.

Test scheme

In Huainan City, Anhui Province, a deep coal mine’s average depth is 836 m, the maximum tectonic stress is 26.8 MPa, the maximum temperature of the original rock is above 45 °C, the average geothermal gradient is 3 °C/hm, and the high water pressure is greater than 4.5 MPa36,37. According to existing research38, rockburst manifests only under pre-static stresses of 25 ~ 50 MPa during dynamic rock compression. Considering the actual situation in deep rock engineering, the rock’s ambient temperature is generally not exceed 100 °C. At this temperature, the temperature field can be applied by heating the sample in a water bath. Therefore, the axial pre-static stress and fixed dynamic impact velocity of the test are 26 MPa and 9 m/s. The impact velocity was captured using an infrared laser velocimeter. During testing, the impact velocity was fixed by setting a constant impact air pressure. Temperatures were set at 33 °C, 39 °C, 45 °C, 51 °C, and 57 °C, while water pressure values were set at 2 MPa, 5 MPa, 8 MPa, 11 MPa, and 14 MPa. Four parallel specimens were prepared for each group, totaling 100 specimens. It is important to remember that to decrease test error and increase test accuracy and reliability, the rock sample of the sounding part needs to be placed in a constant temperature water bath box in the corresponding heating water medium for 48 h before the test, to ensure that the rock reaches the corresponding ground temperature.

Test method

SHPB test

It is worth noting that the constant temperature water bath box is placed in front of the loading position of the SHPB test instrument bar, which is convenient for the test operation to take out the saturated sample and quickly move it into the temperature-water pressure loading device. The 30% pre-static stress is applied first to confirm that the bar is in close connect with the rock, and the sealed end cover is installed. The high and low temperature water bath circulation box heats the water medium to the target temperature in advance and transports it to the surroundings of the test sample, and then applies the pre-static stress to the set value. The water body is heated back and forth for a certain period of time and exhausts the internal air, which is convenient for applying the water pressure to the set value.

P wave test

Before testing, the P-wave velocity of samples was obtained using a seismometer. Following the test, these samples that remained intact after impact was again measured using the seismometer to characterize the dynamic damage extent of deep rock under THM coupling. The seismometer is shown in Fig. 7a.

SEM test

After the dynamic impact post-test under THM coupling, the broken test block was selected from the broken sample and made into the a size sample required for the scanning electron microscope according to the requirements, and then gold was sprayed on the IXRF Model 550i spraying instrument. The scanning test instrument is the FlexSEM1000 scanning electron microscope produced by HITACHI Company in Japan, which can be magnified 16 ~ 800,000 times, with a resolution of up to 5.0 nm, and has two electron and backscatter imaging methods. Finally, the microstructure of granite under different working conditions is obtained. The scanning electron microscope is shown in Fig. 7b.

NMR test

The rock samples after dynamic impact under THM coupling were taken out after being saturated by the pure water vacuum method for 8 h. After taking out, the T2 spectrum distribution test was measured in turn to acquire the pore size distribution characteristics of deep rock under different water pressure conditions. The NMR test is presented in Fig. 7c.

Stress balance verification

The effectiveness of experimental data concerning the dynamic stress and strain properties of deep rock may be assessed by examining stress equilibrium across the specimen’s front and rear surfaces. Specifically, the superposition of reflected and incident waves should substantially consistent with transmitted wave. Only under conditions of stress equilibrium can the obtained ‘dynamic stress–strain curve’ be considered highly credible. The display controller shall show the magnitude of the forward axial compression in real time38. Figure 8a are typical stress wave curves of deep rock under THM coupling. Fig. 8b illustrates that the three-wave stress data have a good coincidence effect, indicating that the deep rock in the thermal-hydro-mechanical coupling environment can basically meet the requirements of stress–strain uniformity assumption during dynamic impact loading.

Test principle

The temperature, water pressure, and axial pre-stress acting upon deep rock specimens constitute static loads. Essentially, both the transmitted and incident bars adhere to the principles of one-dimensional stress wave theory. The signal wave data collected by strain gauges is processed by substituting into the ‘three-wave method’ equation to obtain the sample’s dynamic stress, dynamic strain, and strain rate. This can be obtained from Eqs.(1) ~ (3)39.

In essence, the impact crushing process of deep rock under THM coupling conditions is the process of initiation, propagation, aggregation and final penetration of pore cracks in rock under energy-driven action. The incident energy \(Q_{I}\), the reflected energy \(Q_{R}\), and the transmitted energy \(Q_{T}\) can be represented as follows40:

In the above equation,\(E_{0}\),\(c_{0}\), and \(A_{0}\) are the elastic modulus (N/mm2), wave velocity(m/s), and cross-section area(mm2) of the bar; \(\varepsilon_{I} (t)\),\(\varepsilon_{R} (t)\), and \(\varepsilon_{T} (t)\) are the strains measured on the incident bar, the reflection bar, and the transmission bar at the corresponding time;\(t\) is the stress wave duration(μs).

The experimental analysis presumes the exclusion of frictional effects at the contact surfaces and disregards energy dissipation between the striking bar and elastic member, with the working hypothesis that the impactor’s kinetic energy is fully transformed into incident stress wave energy. The rock dissipation energy \(Q_{S}\), the energy reflection coefficient \(H_{R}\), the energy transfer coefficient \(H_{T}\), and the energy dissipation coefficient \(H_{S}\) are as follows, respectively41,42.

Experimental results

Dynamic stress–strain curve

To a certain degree, the dynamic mechanical response characteristics of the sample can be described by the dynamic stress–strain curve of rock. Fig. 9 illustrates the stress–strain curve of rock under T-H-M coupling. When the water pressure and pre-static stress load remain constant, the stress–strain curves of rock under various temperatures show significant nonlinear characteristics. The three stages are as follows: elastic deformation stage (O-I stage), plastic yield stage (I-II stage), and post-peak failure stage (II-III stage).

-

(a)

During the elastic deformation stage (O-I stage), the pores within the rock are not only filled with water but are also gradually compacted under the effects of pre-existing stress and water pressure. Under the effect of disturbing loads, the water filling the pores within the rock cannot be expelled promptly. As a result, the rock exhibits a strong compressive state under the dynamic loading process, causing the initial segment of the curve to rise approximately linearly. This stage no longer exhibits the pore compaction phase characteristic of uniaxial compression. As dynamic stress continues to increase and temperature rises, dynamic stress concentrates at microfractures within the rock and propagates forward. Microfractures that were previously compacted and closed begin to redevelop. The rate of increase on the stress–strain curve slows down and no longer exhibits a linear rise. At this point, the rock enters the I-II stage.

-

(b)

A distinct “plastic plateau region” appears during the I-II stage. As temperature increases, thermal expansion occurs in the mineral grains within the rock. Under impact loading, the bonding strength between the cementing materials within the rock is weakened due to temperature changes and the influence of pore water pressure. Simultaneously, the specimen itself absorbs dynamic and static load energy43, resulting in enhanced plasticity and an extended elastic–plastic stage, thereby forming the plastic plateau region. When the dynamic stress–strain curve reaches its peak, the rock undergoes macroscopic instability failure and transitions from the plastic yielding stage to the II-III stage.

-

(c)

During the II-III stage, after the dynamic strain reaches its peak value, the dynamic strain reduces slightly, and the dynamic stress decreases rapidly. The II-III stage curve exhibits distinct elastic after-effects, indicating that the rock still possesses bearing capacity, particularly within a certain temperature range and under high water pressure. In some cases, macroscopic failure does not occur in the rock, as the applied external water pressure acts as confining pressure27. Hydrostatic confining pressure exerts a uniformly restrictive effect on internal rock fractures, limiting radial deformation of the rock, thereby enhancing its integrity and uniformity, reducing the degree of specimen fragmentation, and altering the failure mode to exhibit higher impact resistance. Thermal expansion forces and pre-existing stress caused by temperature within a certain range may also contribute to the closure of some primary fractures, preventing further development of internal rock fractures, thereby enhancing the rock’s load-bearing capacity to resist deformation.

Additionally, Fig. 9 displays that when the temperature is below 51 °C, the peak dynamic stress of deep rocks gradually increases with increasing water pressure and rising temperature. When the temperature exceeds 51 °C, the peak dynamic stress of deep rocks gradually decreases with increasing water pressure and rising temperature. This is because the continuous increase in temperature causes inconsistent thermal expansion deformation across grain boundaries within deep sandstone, generating structural thermal stress. This will lead to the production of new microcracks in deep rocks, which, to some extent, deteriorates the internal grain bonding state. As a result, the combined effects of thermal-hydro-mechanical weakened impact resistance, resulting in a gradual decline in peak dynamic stress.

Energy dissipation

Energy and stress-dissipated energy time history evolution

The energy evolution law has been widely applied in rock mechanics research and testing and is a valuable technique for examining the deformation and failure features. From a microscopic perspective, rock deformation, and failure result from the evolution of internal damage, which is created by the continuous propagation of initial defects such as microcracks. During their propagation, microcracks require energy to generate new fracture surfaces. This implies that part of the work done by outer forces on the rock is dissipated by means of microcrack propagation. This portion of energy is referred to as dissipated energy. Based on Eq. (4), the energy time history curves and stress-dissipated energy time evolution curves of deep rocks under different temperatures and water pressures can be observed. Taking the typical energy time history curves and stress-dissipated energy time evolution curves of rocks under T = 39℃and T = 51℃as examples for analysis, as shown in Fig. 10 and Fig. 11, the energy changes exhibit synchronous amplitude characteristics, meaning that the duration of energy action aligns with the duration of stress waves, while the amplitude of changes varies. This is specifically manifested in the following two aspects:

(1) It can be obtained from Fig. 10, the time-history curves of transmitted energy, reflected energy, and incident energy exhibit similar evolutionary characteristics, all increasing with time and eventually stabilizing at a certain level. In contrast, the time-history curve of dissipated energy shows significant differences, characterized by a brief decline after reaching its peak, with the released dissipated energy primarily converting into transmitted energy. During the initial stage of impact loading, reflected energy grows at a substantially slower rate than dissipated energy, with reflected energy being less than dissipated energy. As time progresses, reflected energy gradually exceeds dissipated energy. Additionally, dissipated energy exhibits a brief downward trend, which always occurs after the incident energy stabilizes, indicating that during this stage, secondary and primary cracks within the rock continue to expand and connect, forming an intersecting crack network. When damage accumulation reaches a critical state, energy evolution tends toward a stable value. The underlying cause can be explained as follows: under thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling, the rock sample lacks sufficient stored energy to maintain its load-bearing capacity, leading to its temporary storage of energy by means of elastic energy. This energy is subsequently released in the form of reflected stress waves and transmitted stress waves44.

(2) Figs. 11a ~ c displays the stress-dissipated energy time evolution curves of rocks under various water pressures at T = 39℃. The four stages of the dynamic impact test procedure for deep rocks under THM coupling conditions are as follows:

OA stage (linear elastic stage): Point A represents the point of sudden change in the slope of the dynamic stress-time curve, i.e., the yield point. In OA stage, the dynamic stress rises linearly with time under the action of impact loads, and the original fractures within the rock fail to close under the impact loads, resulting in faster stress growth. The energy dissipated by fragmentation increases slowly and linearly with the propagation of stress waves.

AB stage (crack stabilization and propagation stage): Point B is the peak point of dynamic stress. During this stage, the dynamic elastic modulus dramatically drops, and the dynamic stress-time curve’s slope steadily drops to zero, suggesting that rock cracks are still forming and spreading under the influence of high disturbance loads. After reaching the stress peak at point B, macro-cracks continue to appear; the energy dissipated by fragmentation continues to accumulate, showing a linear upward trend.

BC stage (crack acceleration stage): Point C is the peak point of fracture dissipation energy. In this stage, The dynamic stress-time curve has a negative slope. Under the rapid increase in fracture dissipation energy, macro-scale failure surfaces appear in the rock, cracks keep growing and spreading, and their carrying ability progressively diminishes. However, due to the energy lag phenomenon, the crack propagation velocity has a threshold and reaches its limit before the energy transfer velocity.

CD Stage (Destruction Stage): Point D represents the residual dynamic stress point. During this stage, stress decreases sharply, the slope of the dynamic stress-time curve drops abruptly, moreover, the energy dissipated through fragmentation decreases gradually. Ultimately, the energy is released through the fragmentation of rock blocks, destroying the rock. As water pressure rises, the rebound value of fracturing dissipation energy gradually increases, indicating that the applied water pressure acts as confining pressure, restricting radial deformation and preventing further development of internal fractures. This enhances the rock’s load-bearing capacity to resist deformation, reducing the extent of rock failure. At this point, an increased rebound phenomena in dissipation energy results from an increase in the elastic energy stored in the rock.

Figs. 11d ~ f displays the stress-dissipated energy time evolution curves under various water pressures at T = 51℃. With increasing temperature, the dynamic impact test process of deep rock under THM coupling conditions only includes three stages: the OA stage (linear elastic stage), AB stage (crack stable propagation stage), and BC stage (failure stage). The rock dynamic stress and fracture dissipation energy simultaneously reach their peak values. Additionally, the rebound value of the fracture dissipation energy rises with the increase in water pressure. The times for the increase in dynamic stress in Fig. 11a ~ c are 271.8 μs, 284.2 μs, and 268.4 μs, respectively, which are greater than those in Figs. 11d ~ f, which are 237.8 μs, 255.8 μs, and 217.2 μs, respectively. The primary reason lies in the thermal expansion forces brought on by temperature, which induce friction between mineral particles, leading to mutual compression between particles. The pressure within the pores causes the original internal pores and microcracks to close45, resulting in a more compact internal structure of the rock and enhanced resistance to impact.

Energy reflection coefficient

Fig. 12 illustrates how the energy reflection coefficient of deep sandstone changes with water pressure at varying temperatures while maintaining the same impact force and axial pre-stress. As can be obtained from Fig. 12, with increasing water pressure, the energy reflection coefficient of deep rock first decreases rapidly and then develops gradually. For instance, when water pressure increases from 2 to 8 MPa, the rock energy reflection coefficient decreases sharply. However, when water pressure continues to increase beyond 8 MPa, the rock energy.

reflection coefficient tends to stabilise, with the overall range stabilising between 0.641 and 0.724 under different temperatures. To acquire more information about the variation law of rock energy reflection coefficients under different T-H conditions, the energy reflection coefficients and water pressure data in Fig. 12 were fitted, and it was found that the two satisfy an exponential function relationship

In the equation, \(\alpha\) represents the constant value of the rock energy reflection coefficient under different temperature conditions, with a dimension of 1. Both \(\beta\) and \(\chi\) characterise the rate of change of the rock energy reflection coefficient with water pressure, with a dimension of 1. The fitting curves of the rock energy reflection coefficient with water pressure under different temperature conditions are summarized in Fig. 12, and Table 3 lists the fitting parameter results.

The fit between the fitted curve and the experimental data in Fig. 12 and the fitted correlation coefficients in Table 2 displays that the function has a high correlation coefficient, and the rock energy reflection coefficient exhibits a good exponential relationship with water pressure. This fitted function model effectively characterises the relationship between water pressure and the rock energy reflection coefficient, providing a reference for stress wave energy reflection during dynamic disturbance excavation in underground water-rich engineering blasting operations.

Energy transfer coefficient

The energy transfer coefficient calculated based on transmitted waves can be more effectively used to invert changes in rock wave impedance and accurately characterise changes in rock physical and mechanical properties44. Fig. 13 displays the variation of the rock energy transfer coefficient under the same axial pre-stress conditions and dynamic impact load. The rock energy transfer coefficient rises with increasing water pressure and exhibits an approximately linear upward trend under different temperature conditions. Under different water pressure conditions, the rock energy transfer coefficient first increases and then decreases with increasing temperature. Analysis suggests that when rock is subjected to a specific axial pre-stress, the degree of pore compaction or damage evolution is determined. An increase in water pressure has a dual effect on the rock’s wave impedance, both enhancing and weakening it. The rise in water pressure favours an increase in the rock’s water content, as pores previously filled with air or a vacuum are filled with free water. Since the density of water and its longitudinal wave velocity are greater than those of air, water pressure exerts a circumferential force on the rock, further increasing its density. Both of these effects contribute to an increase in the wave impedance, representing the enhancing effect of water pressure on the wave impedance. However, as water pressure continues to rise, the water content of the rock does not increase significantly; however, the water wedge effect formed by high water pressure promotes the propagation and breakthrough of microcracks in the rock, exacerbating the extent of rock damage and the softening effect of water on the rock, thereby reducing the rock’s wave impedance value. This illustrates how water pressure reduces the impact of rock wave impedance.. At the same time, the increase in water pressure also enhances the circumferential force on the rock, causing the circumferential deformation of deep sandstone to be restricted under the same impact load, making the initiation and propagation of cracks increasingly difficult. The rock’s energy transfer coefficient rises as a result of the majority of the impact energy traveling through it as stress waves. As the temperature gradually increases, the mineral particles inside the rock expand due to heating. The inconsistent thermal expansion and deformation of various mineral particles generate structural thermal stress, causing the original fractures to close. The initial damage to the rock gradually decreases, and its overall wave impedance increases, leading to an overall increase in the energy transfer coefficient. At this point, the enhancing effect of increased water pressure on the wave impedance significantly outweighs its weakening effect, and the transfer coefficient gradually tends toward linear increase. In summary, as water pressure gradually increases, its enhancing effect on rock wave impedance is greater than its weakening effect. As the temperature rises, the enhancing effect becomes increasingly dominant over the weakening effect, and wave impedance tends to increase linearly. However, as temperature continues to rise, the structural thermal stress produced within the rock becomes increasingly significant, and the enhancing effect of temperature on rock wave impedance begins to be outweighed by its weakening effect, resulting in a decrease in the energy transmission coefficient. This suggeststhat the proportion of transferred energy increases with decreasing rock dynamic damage extent. Sandstone is significantly harder than typical coal rock, which is advantageous for the transmission of stress wave energy. Based on wave impedance matching effects, if reflected energy is minimal and dissipated energy is maximised, rock fragmentation is more severe, and energy utilisation efficiency is higher. Therefore, under thermo-hydro-mechanical coupled effects, low-wave impedance explosives should be prioritised for deep engineering rock blasting to effectively enhance blasting energy utilisation efficiency.

Energy dissipation coefficient

Energy accumulation and dissipation cause deep rocks to become unstable and fail46. During dynamic loading, damage and plastic deformation of rocks cause energy dissipation. Energy dissipation deteriorates the dynamic properties of rocks, reducing the cohesion between particles and their resistance to failure. Therefore, dissipation of energy is a crucial characteristic of rock failure, reflecting the process of microcracks continuously forming, propagating, and connecting within the rock. The greater the energy dissipated during rock failure, the more energy the rock requires to dissipate during fracturing, which means that more microcracks must form during rock failure. Fig. 14 shows that the rock energy dissipation coefficient varies with water pressure under the same impact load and pre-stress but different temperature conditions. As can be seen from Fig. 14, water pressure has a crucial impact on the rock energy dissipation coefficient; as water pressure gradually rises, the rock energy dissipation coefficient first rises and then decreases; under different temperature conditions, the energy dissipation coefficient reaches its maximum value when water pressure is around 8 MPa. These results indicate that when water pressure increases to 8 MPa, the increase in water pressure promotes the absorption of rock energy; however, when water pressure continues to increase beyond 8 MPa, the increase in pressure inhibits the absorption of rock energy. According to the analysis, there are two distinct ways that water pressure affects the rock energy dissipation coefficient. The rise in water pressure promotes a rise in the water content within the rock. Under the action of impact loads, the expansion of existing fractures and the formation of new micro-fractures require more energy to overcome the viscous effects of water, leading to an increase in the rock’s energy dissipation coefficient. As water pressure increases, the circumferential forces acting on the rock also increase. Under the same impact load, the rock’s skeletal structure becomes more resistant to deformation, making it harder to fracture, which reduces the rock’s energy dissipation coefficient, moreover, which initially increases due to the rapid increase in free water content within the rock as water pressure rises, leading to an increase in the energy required to overcome the viscous effects of water. At this stage, the rock’s water content holds a dominant role in increasing energy dissipation, thereby increasing the energy dissipation rate of the sandstone. When water pressure continues to increase beyond 8 MPa, the free water content within the rock does not undergo significant changes, and the enhancing effect of water content on energy dissipation gradually weakens; however, the circumferential water pressure acting on the rock enhances its skeletal resistance to deformation. At this point, the reducing effect of circumferential water pressure on energy dissipation becomes dominant, causing the rock’s energy dissipation rate to continue decreasing.

Additionally, when the temperature rises from 31 °C to 51 °C, the energy dissipation coefficient shows an overall decreasing trend. The rock requires less energy to dissipate during the dynamic fracture process, resulting in fewer microcracks during failure and an overall reduction in the severity of failure. This indicates that temperature plays an inhibitory role in internal damage to the rock during this process. When the temperature continues to rise to 57 °C, the energy dissipation coefficient begins to increase gradually. The rock requires more energy to dissipate during dynamic fracturing, resulting in the formation of more microcracks during failure and an overall increase in the severity of damage. This suggests that temperature plays a promoting role in internal injury to the rock during this stage.

In conclusion, the dual impacts of increased and diminished energy absorption by the rock during the rise in water pressure are responsible for the variable pattern of the energy dissipation coefficient illustrated in Fig. 14. The slope of the variation curve represents the difference between these dual effects; When the slope is positive, the enhancing effect dominates, and rised water pressure promotes rock energy absorption; when the slope is negative, the weakening effect dominates, and increased water pressure inhibits rock energy absorption.

To obtain more information on the variation of the water pressure with energy dissipation coefficient, the energy dissipation coefficient and water pressure in Fig. 14 were fitted. Table 3 displays that the fitting equation and fitting parameters.

In the table,\(\kappa\) represents the minimum energy dissipation coefficient of rock, \(\gamma\) represents the critical water pressure, with units in MPa. When σw is less than \(\gamma\), the rock energy dissipation coefficient rises with increasing water pressure; When σw exceeds \(\gamma\), the rock energy dissipation coefficient decreases with rising water pressure. Considering the characteristics of the Gaussian function,a larger parameter \(\delta\) indicates a broader range of water pressures influencing the energy dissipation rate. Therefore,\(\delta\) represents the sensitive water pressure range, with units in MPa. Additionally, according to the fit between the fitted curve and experimental data in Fig. 14 and the correlation coefficients in Table 4, which displays that the rock energy dissipation coefficient exhibits a good Gaussian function distribution with respect to water pressure.

Macro-dynamic damage characteristics

Destruction mode

Analyzing the failure patterns of rocks subjected to strong disturbances can provide the most direct criteria for safe excavation and stable support of surrounding rock in deep coal47. Typical failure patterns of rocks under different temperature conditions and water pressure are listed in Table 4. Under the coupled effects of temperature, water pressure, and stress, the lateral cracks in rocks are mainly shear cracks. As water pressure gradually increases, the development scale (number, length, and width) and failure severity of lateral shear cracks in rock decrease. This is because, as water pressure rises, the viscous effects generated by free water within the rock gradually strengthen, and water pressure can restrict lateral deformation of the rock, thereby inhibiting the initiation and propagation of microcracks. As shown in the table, under the same temperature conditions (33 °C), when water pressure is low, rock damage is most pronounced, with irregular polygonal fracture surfaces and relatively large.

fragment sizes. When water infiltrates the rock, soluble salts dissolve and colloidal minerals hydrolyze, transforming the original bonds into hydrogel bonds. The bonding strength between mineral particles weakens, friction decreases, and water in the surrounding environment produces a lubricating effect on discontinuous surfaces. The shear stress effect on discontinuous surfaces is enhanced, leading to the fragmentation of rock pieces along shear cracks, with shear edges exposed. The ultimate failure mode of the rock is compression-shear crushing failure. When water pressure is high, shear cracks are only distributed in the rock boundary area, and the degree of dynamic impact damage is reduced. One-quarter of the rock is broken, while three-quarters remain relatively intact. The damaged fragments are mostly from the sample boundary area, with the fragments being thin and elongated.

The rock failure mode is inclined shear boundary failure, corresponding to the flaking phenomenon of the deep surrounding rock. Under the same water pressure conditions (8 MPa), as the temperature increases, the rock mass remains intact, with only shear cracks forming at a certain angle to the impact stress on the sides. Ultimately, no failure occurs, and the rock failure mode is fracture failure. Analysis suggests that rising temperatures cause thermal expansion of mineral particles within the rock, leading to deformation and the generation of structural.

SC represents a shear crack.

thermal stress. When thermal stress and water pressure are coupled, the interlocking forces between different mineral grains strengthen, causing their original microcracks to close. Additionally, free water within the rock inhibits the further development of microfractures triggered by structural thermal stress, causing the total amount of rock failure to diminish as well as the quantity of microcracks.

Damage variable

To characterize changes in the extent of dynamic damage to deep rock under THM coupling, the P-wave velocity of specimens that did not undergo overall fragmentation after impact was measured using a seismic velocity meter. Relative velocity and damage degree were used as evaluation parameters to assess the extent of internal damage to deep rock after impact under THM coupling:

where,\(D\) represents the damage variable, \(V_{T}\) represents the relative wave velocity, \(V_{m}\) reprensents the P-wave velocity of the rock that has not undergone compressive shear crushing failure after the impact, and \(V_{0}\) represents the P-wave velocity of the rock before the impact.

The longitudinal wave velocity, relative wave velocity, and damage degree of rock without compression-shear crushing failure after impact under THM coupling are displayed in Table 6. Under the impact of THM coupling, the rock under some working conditions has undergone compression-shear crushing failure, and its longitudinal wave velocity cannot be measured, so it is not listed in the table. According to the test data in Table 5, the damage.

variable \(D\) and the relative wave velocity \(V_{T}\) of the rock after the impact load change with the water pressure, as displayed in Fig. 15. The deep rock without compression-shear crushing failure after impact under THM coupling, the relative wave velocity increases with the rise of water pressure, while the rock damage variable is smaller and the decreasing trend is gradually gentle. Under the same water pressure condition, the greater the overall temperature, the smaller the damage degree of the rock after the impact. Combined with the previous analysis, the increase in water pressure has both strengthening and weakening effects on the resistance of rock to deformation under impact. The enhancement effect reduces the damage degree of rock after impact, and the weakening effect leads to the gradual decrease of damage variable. Additionally, combined with the evolution law of rock energy dissipation coefficient with water pressure, it can be seen that it is consistent with the evolution law of damage variable of rock without compression-shear crushing failure after impact, which can be proved by each other. In addition, combined with the statistical rock damage variable and the actual damage degree, the damage threshold Dcr corresponding to the rock under THM coupling and impact load can be delineated between 0.35 and 0.36, that is, the imaginary line position in the graph. When the damage variable D is less than the damage threshold Dcr, there are only tiny cracks on the rock surface, and no fragments are falling off, and the rock integrity is better. The majority of working situations in engineering practice allow for the monitoring or control of the water pressure and temperature range. According to the size of water pressure and temperature, the macroscopic damage degree and range of rock mass are determined, and the ultrasonic test is used to verify the feedback. It can provide a reference for engineering construction design.

Meso-microscopic structures

Meso-structure

A detailed examination of the fracture process reveals the complex evolution of primary fractures along weak structural planes in rock masses under the effect of stress waves. To further analyze the dynamic failure mechanisms under the combined effects of “three highs and one disturbance,” a Bystronic electronic digital microscope magnified 1000 times was used to examine typical failure surfaces of rock masses subjected to temperatures of T = 45 °C and stress levels of σw = 5 MPa, 11 MPa, and 14 MPa, as presented in Fig. 16. Some areas of the rock failure surface still have structurally weak surfaces formed by primary joint layers and cavities. Under external loads, these structurally weak surfaces undergo complex evolution, with mineral particles peeling away from each other, forming a great amount of new cracks and nurturing them. The cracks interconnect with each other, ultimately causing the rock to fail along the structurally weak surfaces. Figure 16a shows the microstructure at the rock failure surface when σw = 5 MPa. At this point, fracture propagation is primarily driven by stress waves, causing the mineral grains within the rock to transition from a state of equilibrium to a state under stress. This leads to the nucleation, propagation, and formation of numerous new fractures, joints, and faults at the original defects within the rock structure (such as bedding planes, joints, and primary fractures). Figs. 16b and c

show the microstructures at the rock failure surface when σw = 11 MPa and 14 MPa, respectively. It can be obtained that as σw rises, the width of fractures, joints, and faults at the rock failure surface decreases, and the extent of internal damage to the rock gradually decreases. This indicates that increased water pressure can promote the closure of natural fissures, hinder the formation and expansion of new fractures, and, on a macroscopic scale, prevent rock debris from flying, thereby constraining lateral deformation of the rock. Thus, water pressure has a certain strengthening mechanism on the weak surfaces of the internal structure of rock under specific multi-field coupling conditions.

Microstructure test

SEM can observe the local microstructure of deep rock cross-sections, thereby revealing the patterns of change in the internal pore and fracture structures of rocks. Using SEM to scan the microstructure of rock fracture surfaces after exposure to a temperature of 33 °C and different water pressures, as depicted in Fig. 17. After undergoing thermal-hydro-mechanical coupled effects, the internal fracture surfaces of the rocks are covered with a large amount of rock debris. The fracture surfaces are overall rough and uneven, with poor uniformity. The rock debris attachments are primarily fine-grained minerals, with loose intergranular cementation and widespread development of microcracks. Rock itself is composed of mineral particles of various sizes and types that are cemented together. The infiltration of water causes the hydrophilic minerals and cementing agents within the rock to undergo physical and chemical dissolution reactions. In this process, hydrophilic mineral particles undergo ion.

exchange with water, thereby weakening the bonding between mineral particles and ultimately resulting in the formation of more fractures within the rock. As seen in Fig. 17a and b, when water pressure is low, there are more cracks between mineral particles within the rock, resulting in a looser particle structure and a rough surface texture. As water pressure increases, as depicted in Fig. 17c ~ e, the number of fractures within the rock gradually decreases. The increased external water pressure causes the micro-pores between mineral particles to close, while the small fractures interconnect to form elongated cracks, resulting in a smooth surface texture. As can be obtained from Fig. 17, when σw is 2 MPa and 5 MPa, the structure between mineral particles gradually becomes loose, with some particles directly detaching from the cross-section. The surface becomes uneven, with irregular edges and corners appearing. The fracture surface exhibits a large amount of intact crystal particles, and intergranular fractures occur in the weakly bonded cemented phases. The primary form of fracture within the rock.

is intergranular fracture. Analysis of causes: The primary stress acting on the rock stems from axial impact disturbances and pre-existing stress. These unidirectional mechanical effects cause mineral particles to preferentially choose easier failure paths48, i.e., failure of the cementing phase between mineral particles, resulting in intergranular fracture. When σw is 8 MPa and 11 MPa, the fracture surface simultaneously exhibits separated crystal particles and open cracks penetrating the particle surfaces, combining both intergranular and transgranular fracture characteristics, constituting a composite fracture. When σw increases to 14 MPa, the edges of the rock’s internal fracture surface become sharp and distinct, with a more compact internal structure. Adjacent mineral particles have flush fracture surfaces, primarily characterized by face-to-face contact. Microfractures run straight through the entire particle, with intergranular fracture occurring directly within the crystal grains, exhibiting strong shear fracture characteristics. At this point, the primary fracture form within the rock’s internal fracture surface is intergranular fracture. On account of the rise in water pressure, the lateral stress state of the rock becomes more pronounced, while the development time of microfractures is extremely short. Under the coupled effects of thermal, hydrothermal, and mechanical forces, most mineral grains do not have sufficient time to select weaker failure paths, making intergranular fracture more likely to occur.

Pore structure characteristics

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) technology can accurately determine the porosity, permeability, and pore size distribution of rocks. NMR testing yields the T2 relaxation time spectra of rocks at T = 51℃ under different water pressures, as illustrated in Fig. 18. A leftward shift in the T2 spectrum curve indicates a decrease in the pore size within rock interiors, while an upward rise in the T2 spectrum curve indicates an rise in the number of pores with identical aperture49. It can be obtained that under THM coupling, the T2 distribution curve of the rock exhibits a bimodal shape (main peak and secondary peak), with the amplitude of the main peak being significantly higher than that of the secondary peak. Under the same temperature conditions, the amplitudes and areas corresponding to the secondary peak and main peak decrease with increasing water pressure. For rock samples subjected to a temperature of T = 51℃, the main peak area and secondary peak area at σw = 2 MPa are 12,304 and 559, respectively. At σw = 5 MPa, 8 MPa, 11 MPa, and 14 MPa, the main peak areas decrease to 11,522, 10,432, 9,708, and 9,131, respectively, with decreases of 6.4%, 15.1%, 21.1%, and 25.8%. The secondary peak areas at σw = 5 MPa, 8 MPa, 11 MPa, and 14 MPa were 512, 497, 463, and 444, respectively, representing reductions of 8.4%, 11.1%, 17.2%, and 20.6% compared to the secondary peak area at σw = 2 MPa. Additionally, as water pressure increases, both the main peak and secondary peak exhibit a trend toward leftward shift, reflecting the process of pore enhancement in rock samples under water pressure. For instance, when water pressure rises from 2 to 14 MPa, the T2 spectral values corresponding to the main peak of the rock are 0.61 ms, 0.52 ms, 0.43 ms, 0.42 ms, and 0.41 ms, respectively. Among these, the T2 spectrum values of the main peak under water pressures of σw = 5 MPa, 8 MPa, 11 MPa, and 14 MPa decreased by 14.7%, 29.5%, 31.1%, and 32.8%, respectively, compared to those under σw = 2 MPa.

Fig. 19 shows the distribution of amplitude values corresponding to the main peak and secondary peak of rock under different water pressures. When the temperature remains constant, as water pressure rises, the amplitudes corresponding to the main peak and secondary peak in the rock T2 spectrum curve gradually decrease. At σw = 2 MPa, the amplitude corresponding to the main peak is 444.37, and at σw = 5 MPa, 8 MPa, 11 MPa, and 14 MPa, the corresponding amplitudes decrease to 377.71, 347.78, 338.61, and 287.82, respectively, with decreases of 15%, 21.7%, 23.8%, and 35.2%; at σw = 14 MPa, the amplitude corresponding to the secondary peak is 35.27, while at σw = 2 MPa, 5 MPa, 8 MPa, and 11 MPa, the amplitudes corresponding to the secondary peak are 42.35, 41.97, 40.06, and 38.91, respectively, representing increases of 20%, 19%, 13.6%, and 10.3% compared to the amplitude corresponding to the secondary peak at σw = 14 MPa. These data provide a more intuitive understanding of the evolution of pore structure in rocks under multi-field coupling and impact loads. Changes in pore structure affect the physical and mechanical properties of rocks. Analyzing changes in the pore structure of deep rocks under different water pressures can offer a theoretical basis for rock engineering design and stability assessment, helping to optimize solutions and reduce risks.

Studies on rock nuclear magnetic resonance testing have confirmed that T2 has the property of reflecting the pore size distribution and size within the rock. In rock pore fluids, there are Three types of relaxation mechanisms: surface, diffusion, and volume relaxation. Among these, surface relaxation and volume relaxation affect both T1 and T2, while diffusion relaxation under a magnetic gradient field only affects the transverse relaxation time T2. The three relaxation effects influencing T2 are given by Eq. (14):

In the equation, \(T_{2}\) represents the transverse relaxation time of nuclear magnetic resonance, ms;\(T_{2B}\) represents the transverse volume relaxation time in the core fluid, ms;\(T_{2S}\) represents the transverse surface relaxation time, ms;\(T_{2D}\) represents the diffusion relaxation time of pore fluid in gradient nuclear magnetic resonance, ms.

In Eq. (14), \(T_{2B}\) is determined by the fluid in the pores, and \(T_{2S}\) represents a relationship related to the pore size. During the experiment, since the rock was completely immersed and saturated with water, the volume relaxation rate of water \(T_{2B}\) was extremely large, and 1/\(T_{2B}\) could be neglected. In this case, 1/\(T_{2D}\) was also very small, and the bond T2 with the pore size could be approximately simplified to50:

In the equation, \(\rho_{2}\) represents the surface relaxation rate; S and V represent the surface area and fluid volume of the pores, respectively. Therefore, the distribution of the T2 spectrum can reflect the pore size distribution characteristics of the rock. The pore structure of sandstone is intricate and varies greatly in size. Research has found that the difference between large and small pore sizes can be as much as five orders of magnitude, resulting in different compressibility of pores of different sizes when subjected to external forces. Currently, based on capillary cohesion theory, scholars at home and abroad have proposed some pore size classification methods, but there is no unified standard for accurately classifying sandstone pore sizes. The sandstone pore size classification method proposed by Song51 was adopted to classify pore sizes into three scale ranges: microporous(\(r_{c}\) ≤ 0.1 μm), mesoporous(0.1 μm < \(r_{c}\) ≤ 1 μm), and macropores(\(r_{c}\) > 1 μm). The schematic diagram of rock pore size classification is summaried in Fig. 20a.

Figs. 20b ~ f displays the pore size distribution features of rock pores under various water pressures. The water pressure has a promoting effect on the pore size distribution of deep rock samples. As water pressure increases, the porosity of pores of different diameters decreases significantly, and the total porosity decreases with increasing water pressure. Under the same temperature conditions, the pore size distribution characteristics of rock samples under different water pressures remain largely consistent, primarily consisting of micro-pores, with a relatively small proportion of mesopores and macro-pores. Additionally, comparative data under different water pressures dispaly that the proportion of porosity in each pore size distribution range decreases as water pressure increases. According to the above results, the analysis shows that the mechanical mechanism behind this phenomenon arises from the application of water pressure, which is similar to the confining pressure effect. Confining pressure constrains the pore structure of rocks, and high confining pressure hinders the stress wave propagation, limiting rock deformation and changes in pore structure. To a certain extent, it exerts a compaction effect on the micro-pores of rocks, with the restrictive effect becoming stronger as water pressure increases. Additionally, thermal expansion forces caused by temperature and pre-existing stress within a certain range also contribute to the closure of existing fractures, preventing further development of internal fractures in the rock. This enhances the rock’s ability to resist deformation. Therefore, as water pressure increases, the pore diameters within the rock gradually decrease, and the total porosity gradually decreases. The mechanical characteristics of rock are directly impacted by changes in the distribution of pore sizes, such as strength and toughness. By analyzing changes in pore size distribution, we can provide a microscopic explanation and prediction of the mechanical characteristics of rock in engineering applications. For example, in engineering projects such as tunnel excavation and mine blasting, understanding the rock’s dynamic mechanical properties changes after THM coupling and impact can help us design reasonable construction plans and ensure engineering safety.

Discussion

Sandstone is a typical aggregate polycrystalline material with numerous micro-pores and micro-cracks within its structure. Under THM coupling conditions, Because of thermal expansion anisotropy within a single mineral particle and thermal expansion mismatches between distinct mineral particles, the rock may develop intergranular and intragranular micro-cracks. Moreover, under the influence of pore water pressure and shear stress, existing micro-cracks may also propagate and extend. Therefore, based on the Ashby-Sammis microscopic mechanical model53, a THM-coupled and impact load-induced microcrack propagation model is established to reflect the dynamic mechanical feature of brittle rocks. This model aims to investigate the effect mechanism of THM coupling conditions on microcrack propagation pathways during the dynamic failure process of deep rocks, thereby providing an intuitive understanding of the internal damage evolution patterns and dynamic failure mechanisms of rocks. Fig. 21 displays a schematic diagram of the rock internal slip-type crack propagation model under THM coupling and impact loading. Water pressure, axial static stress, and uniform impact stress are applied to the rock’s far-field boundary. The microcrack surface encounters pore water pressure, and the crack tip experiences thermal expansion stress as a result of the rock’s complete saturation and the mineral particles’ thermal expansion. It is assumed that the sum of the axial static stress \(\sigma_{s}\) and the impact stress \(\sigma_{d}\) equals the maximum principal stress \(\sigma_{1}\), and the water pressure \(\sigma_{w}\) equals the second principal stress and the minimum principal stress \(\sigma_{3}\), i.e.:

Microcracks include initial cracks and wing cracks at an angle of \(\sigma_{1}\) to \(\phi\) degrees with respect to the direction of the maximum principal stress, with lengths of \(2a\) and \(l\), respectively. According to previous researchError! Reference source not found., the following is a simplified version of the wing fracture propagation path: under the influence of the stress intensity factor, the crack first propagates at a large angle along the direction of compressive stress, and ultimately fractures quickly follow the path of compressive stress. Meanwhile, shear stress \(\tau\) and normal stress \(\sigma_{n}\) are generated by the far-field stress during the initial crack slip. Under THM coupling conditions, these stresses can be calculated using Eqs. (13) and (14) based on the coordinate transformation of stress components.

In the equation, \(P_{w}\) represents pore water pressure, and \(\lambda\) represents the water wedge coefficient, which is related to the water wedge effect within the rock. Due to the rapid disturbance and impact loads on the rock, the water contained in the internal microcracks cannot be expelled in time, so it can be considered that the rock is undrained at this time. The pore water pressure is influenced by external loads and is not simply equal to the water pressure. Based on the pore elasticity theory, the pore water pressure \(P_{w}\) within the rock in an undrained state is related to the average stress \(P\)54, with the calculation equation being:

In the equation, \(\xi\) is the Skempton coefficient.

Under the action of stresses \(\sigma_{n}\) and \(\tau\), the wedging force \(F_{3}\) represents the sliding component parallel to \(\sigma_{3}\) (resisted by the friction force between the crack surfaces), which acts on the midpoint of the main crack, resulting in the wing crack to open. This can be obtained from Eq. (16).

In the equation, \(f_{d}\) represents the coefficient of kinetic friction between the crack surfaces, assuming that the friction force is uniformly distributed across the crack surfaces, and \(\tau - f_{d} \sigma_{n}\) represents the effective shear stress on the crack surfaces. The wedging force \(F_{3}\) produces a stress intensity factor \(K_{I(F)}\) at the tip of the wing crack, which can be obtained from Eq. (17)[55].

Water pressure similar to confining pressure can restrain the propagation of wing cracks, while pore water pressure splitting can promote the propagation of wing cracks. Therefore, the stress intensity factor \(K_{I(w)}\) at the end of the wing crack in the combined effect of pore water pressure and confining pressure can be determined using the following Eq. (18).

Similarly, changes in temperature cause thermal expansion deformation of minerals within rocks. When the temperature \(T_{{}}\) exceeds the threshold temperature \(T_{e}\), the thermal expansion force generated by temperature transforms into structural thermal stress and acts on the periphery of wing cracks. Therefore, the structural thermal stress of rocks caused by temperature changes produces a stress intensity factor \(K_{I(T)}\) at the ends of wing cracks. The specific calculation equation is determined by Eq. (19).

In the equation, \(E\) and \(\mu\) represent the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of the mineral grains, respectively, \(\alpha_{T}\) represents the thermal expansion coefficient, and \(\Delta T\) represents the temperature change value.

In the context of THM coupling, the crack-crack interaction should be taken into account in addition to the combined effects of external load, thermal expansion stress, and internal pore water pressure. For the rock material with multiple cracks, the internal micro-cracks continue to expand under the action of outer loads, and the rock bridge between cracks will be damaged. The adjacent cracks penetrate each other, resulting in the overall instability and failure. Combined with the calculation equation of thermal expansion stress \(\sigma_{T}\)21, the calculation equation of the average internal stress \(\sigma_{3}^{i}\) on the rock bridge with no crack ligament length \(S - 2(l + a\cos \phi )\) between the wing cracks in the \(\sigma_{3}\) direction can be expressed as follows :

where \(N_{A}\) represents the amount of compression-shear cracks per unit area.

Due to the existence of \(\sigma_{3}^{i}\), there will be an additional stress intensity factor \(K_{I(\sigma )}\), namely:

The dynamic stress intensity factor \(K_{Id}\) generated at the end of the wing crack propagation process under THM coupling and impact load conditions can be obtained by the simultaneous Eqs. (17), (18), (19) and (21), and \(K_{Id}\) is the only physical quantity that needs to be determined to characterize the stress field characteristics at the crack end.

Based on fracture mechanics criteria and using Eqs. (1) to (6) to solve Eq. (12), we can obtain the stress intensity factor expression for the interaction between rock wing cracks under THM coupling and impact load conditions:

where:\(A = \sin 2\phi \sin \phi - f_{d} \sin \phi (1 - \cos \phi )\)

Under static loading, when the stress intensity factor is up to the static fracture toughness of the rock, cracks begin to develop and propagate within the rock, ultimately leading to macroscopic failure of the rock. Under impact loading, due to time-dependent processes near the crack tip, the dynamic fracture toughness is significantly larger than the static fracture toughness56. Therefore, microcracks in rock are less likely to propagate under dynamic loading, and a greater load is required to cause rock failure. This is also one of the primary causes of rock’s greater dynamic strength than static strength. The dynamic stress intensity factor and dynamic fracture toughness at the crack tip are both time-dependent under dynamic loading since the load changes with time. Previous studies have shown that the two exhibit an exponential relationship57. Therefore, the crack propagation criterion for a dynamic slip-type crack model with multiple crack interactions can be calculated as:

In the equation, \(K_{ID} (t)\) is the dynamic fracture toughness, \(K_{Id} (\sigma ,t)\) represents the dynamic stress intensity factor of the dynamic slip model of multiple crack interaction, which is mainly related to the applied stress \(\sigma\) and the load application time.

To calculate the \(K_{ID}\) and \(K_{Id}\) of rock under THM coupling and impact loading, the parameter values in Eq. (13) are as follows: \(\sigma_{3} = \sigma_{w}\) = 3 MPa、8 MPa and 14 MPa, coefficient of thermal expansion \(\alpha_{T}\) = 5 × 10–6/K, modulus of elasticity \(E\) = 100GPa, poisson ratio \(\mu\) = 0.4, water wedge coefficient \(\lambda\) = 1.5, \(S\) = 6 mm, crack angle \(\phi\) = 45°, coefficient of kinetic friction \(f_{d}\) = 0.75, Initial crack length \(a\) = 1 mm, General definition of normalized crack length \(L = {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$l$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {l a}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{$a$}}\) = 1, Skempton coefficient \(\xi\) Affected by effective stress, changes occur depending on the axial static stress and water pressure exerted on the rock. The values of the Skempton coefficient of sandstone under various working conditions are listed in Table 6[6], \(T\) = 51℃and 57℃, \(\sigma_{1} = \sigma_{s} + \sigma_{d}\) includes dynamic loads \(\sigma_{d}\) that vary over time, calculated from transmitted wave, reflected wave, and incident wave data tested by the SHPB data acquisition system. Substituting the above parameter values into Eqs. (13) and (14) yields the \(K_{Id}\) and \(K_{ID}\) as functions of temperature and water pressure, as listed in Fig. 22.