Abstract

Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome (SAHS) is a prevalent sleep disorder associated with substantial health risks, highlighting the need for improved public awareness. This cross-sectional analysis systematically evaluated the quality of SAHS-related videos on YouTube, Bilibili, and TikTok. Of 903 videos initially identified, 227 met the inclusion criteria for analysis. Cross-platform comparisons revealed that long-form platforms hosted higher-quality content, whereas short-form platforms generated greater engagement despite lower informational integrity. This study reveals a structural disconnect between informational quality and audience engagement, consistent with theories of algorithmic filtering. While professional identity remains a reliable predictor of quality, user engagement is largely driven by peripheral cues rather than medical accuracy. This study further contributes to the theoretical understanding of online health communication by situating platform-specific patterns within broader frameworks of algorithmic curation, heuristic processing, and trust formation. By integrating these theoretical perspectives with empirical quality assessments, the study offers a conceptually grounded explanation for why medically accurate content often remains less visible within algorithmic media environments. These findings underscore the need for platform-specific interventions that integrate credibility signals into recommendation algorithms to mitigate the spread of low-quality health information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome (SAHS) is a common sleep disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of apnea and hypoventilation during sleep, frequently accompanied by loud snoring, pauses in breathing, and abrupt gasps1. Beyond disturbing sleep quality, SAHS has broad adverse effects on both physical and mental health. Patients may experience depression, anxiety, and chronic fatigue, and the syndrome is recognized as a major risk factor for systemic diseases such as heart failure, stroke, coronary artery disease, and hypertension2,3,4. Epidemiological studies indicate that the prevalence of SAHS is approximately 2%–4% in the general adult population, increasing to 20%-40% among individuals aged over 65 years and exceeding 50% in obese patients5. Without treatment, the five-year mortality rate in severe cases may reach 11%–13%6. Despite these risks, public awareness of SAHS remains limited. Many individuals ignore the symptoms, which delays timely medical evaluation and treatment7. Consequently, improving public awareness and recognition of SAHS is of considerable clinical and public health importance.

With the rapid growth of social media, online video platforms have become major channels for health information dissemination8. Compared with traditional text-based resources, videos provide vivid, intuitive, and easily accessible communication, and have gradually become the preferred medium through which the public obtains health information. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, TikTok generated more than 93.1 billion video views in July 2020 alone9. However, analyses revealed that only 15.66% of these videos contained useful health information, whereas 66% disseminated misleading or false advice, underscoring the generally low quality of online health content9.

This context highlights a critical paradox: while public reliance on social media for health information is increasing, the reliability of this content remains highly variable. Numerous studies indicate that the dissemination of health misinformation is not random; rather, it is systematically linked to the “engagement logic” of these platforms. Algorithms prioritize content that elicits strong emotional responses and immediate interactions, such as likes and shares. Consequently, emotionally charged, simplified narratives often achieve greater visibility than complex, evidence-based information, fostering a prevalence of "high engagement, low quality" content10,11. This phenomenon has been substantiated across various health domains, including COVID-199 and oncology12,13. However, when applied to the specific context of SAHS, these dynamics significantly exacerbate public health risks14.

Globally, YouTube remains the most widely used video platform, although it is inaccessible in mainland China7. In the Chinese market, TikTok and Bilibili dominate the short-form and long-form video sectors, respectively8,15. Short-form videos such as those on TikTok are popular for their ease of production and high user engagement (likes, comments, and shares). However, the lack of rigorous quality control mechanisms raises concerns about misinformation dissemination15. Bilibili, known for its longer videos and diverse formats, shows considerable variability in quality depending on the uploader’s background12,13. Although SAHS-related videos are abundant across platforms, their scientific accuracy and reliability have not yet been systematically evaluated. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to investigate the "quality-engagement" paradox through a cross-platform comparison. While this phenomenon has been characterized in prior research, it remains empirically unexplored within the specific context of SAHS.

Recent theoretical frameworks suggest that algorithmic curation prioritizes engagement—driven by emotional salience and visual stimulation—over informational accuracy16,17. Although ranking algorithms remain opaque, the “hypernudge” paradigm indicates they function as attention-maximizing filters that systematically marginalize evidence-based medical discourse16. Concurrently, users with limited digital health literacy often rely on heuristic cues, such as popularity metrics, rather than systematic evaluation to assess credibility18. Trust formation is heavily influenced by these peripheral signals, enabling non-professional creators to establish credibility through high production values19. These mechanisms are particularly critical for SAHS, where patients frequently depend on digital resources for risk interpretation and self-management7. Culturally, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) introduces a distinct analytical dimension. TCM narratives, grounded in holistic reasoning and syndrome differentiation, often conflict with the rapid, reductionist nature of algorithmic platforms20. Therefore, the underrepresentation of TCM content reflects not only uploader demographics but also a profound epistemological misalignment between TCM discourse and the dominant formats dictated by platform algorithms21. This structural tension provides essential context for interpreting the cross-platform discrepancies observed in this study.

Synthesizing these perspectives moves beyond disparate literature to establish a coherent analytical framework for this study. Specifically, algorithmic curation theories elucidate the structural biases that privilege emotionally salient and visually stimulating content11,16; Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM) accounts for user reliance on peripheral cues over systematic evaluation, particularly under conditions of information overload18; and digital trust frameworks reveal how credibility is constructed through interface design, fluency, and platform-native aesthetics rather than traditional professional markers19,22. This unified conceptual lens reconceptualizes SAHS videos not merely as informational objects but as sociotechnical artifacts—products of the interplay between platform incentives, cognitive constraints, and digital communication norms.

While existing research has assessed the quality of health information on social media, it remains largely confined to descriptive comparisons or single-platform analyses. These studies often lack an integrated perspective that synthesizes platform architecture, user cognition, and dissemination mechanisms. Integrating algorithmic curation theory16, HSM18, and digital trust formation framework19, this study constructs a "Platform-Cognition-Trust" triadic framework. This model aims to elucidate the structural disconnect between information quality and user engagement across platforms. Guided by this framework, we integrate validated quality assessment tools with engagement metrics from YouTube, Bilibili, and TikTok. Rather than claiming causality from cross-sectional data, the analysis focuses on uncovering associative patterns among uploader identity, content presentation, and platform structure that jointly shape information visibility. This theory-driven approach advances the analysis beyond descriptive assessment, offering a systematic explanation for health information circulation in algorithmic environments. Furthermore, by examining how "platform-cognitive" interactions influence digital trust, it bridges the fragmentation often found in prior research, addressing the complex interplay between sociotechnical contexts and user psychological processes.

Method

Search strategy

Before collecting video characteristics, we developed a preliminary list of candidate keywords related to SAHS, based on clinical guidelines, medical terminology databases (MeSH), and commonly used lay expressions. The keywords included "Sleep Apnea," "Obstructive Sleep Apnea," "Obstructive Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome," "Central Sleep Apnea," and "Sleep-Disordered Breathing," along with their Chinese equivalents. To verify the coverage and retrieval efficiency of the candidate keywords, a preliminary search test was conducted on January 20, 2025, comparing the number and relevance of search results generated by different keyword combinations across the three platforms. The results indicated that using a single keyword, "Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome" (in English) or "睡眠呼吸暂停综合征" (in Chinese), yielded video sets highly overlapping with those retrieved using multiple keywords. This finding demonstrated that the single keyword approach provided both strong representativeness and retrieval efficiency. Therefore, to ensure consistency and comparability in the search strategy, the study adopted "Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome" as the keyword for YouTube and its Chinese equivalent "睡眠呼吸暂停综合征" for Bilibili and TikTok. Notably, the preliminary search revealed that using this precise term produced results highly similar to those obtained with broader terms such as “Sleep apnea”.This finding aligns with the characteristics of modern information retrieval systems, whose algorithms incorporate query expansion and semantic understanding to recognize associations among core medical terms and return highly consistent content sets23. In addition, broader lay terms such as “Snoring” or “Apnea symptoms” were excluded. The preliminary search showed that such terms, particularly “Snoring”, retrieved numerous videos unrelated to SAHS—such as those about general snoring, other sleep disorders, or non-specific breathing difficulties—thus compromising analytical accuracy and specificity. Considering the language sensitivity of platform search algorithms, mixed Chinese-English queries were not included in the formal search process, thereby ensuring methodological consistency and result comparability24. The formal search was conducted on February 11, 2025.

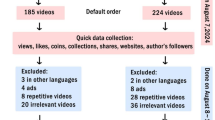

To minimize potential bias from personalized recommendations, all accounts were logged out, browser caches and search histories were cleared, and new accounts were created prior to conducting the searches. All results were displayed under the “default sorting” option without applying any filters. To avoid unstable engagement metrics and ensure reliability, we excluded videos uploaded within the two weeks preceding the search date. Given the global coverage of the three platforms, nearly all non-English and non-Chinese videos were reposts rather than original uploads. Videos were excluded if they involved infants, were not in English or Chinese, duplicated other videos, were irrelevant to SAHS, or consisted primarily of advertisements (see Additional File 1). The detailed screening process and quantitative breakdown of exclusions are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1). One researcher performed video collection and downloading, while two additional researchers independently categorized the videos and classified uploaders. When discrepancies in classification or scoring occurred, the research team initiated a structured group review. All team members jointly reviewed the metadata and content of disputed videos according to predefined classification criteria, focusing on cases that were difficult to categorize. If consensus could not be reached, a senior respiratory expert not involved in the initial coding made the final decision. All disputed cases and adjudication results were documented to ensure full process traceability and transparency.

Video content

On the same day, two researchers systematically recorded multiple attributes for each video, including: (1) basic features (e.g., duration, upload date) to characterize the video and enable platform-level comparisons; (2) audience interaction metrics (e.g., watch time, view count, likes, comments, collections, shares, paid-access options) to quantify dissemination breadth and user engagement; (3) source and contextual information (e.g., uploader identity, channel features) to assess content provenance and presentation; and (4) accessibility indicators (e.g., paid-access options) to evaluate barriers to information access and potential commercial attributes (Additional File 1). These metadata constituted preliminary dimensions for evaluating video informational value and complemented the standardized content-focused tools used later (PEMAT, VIQI, etc.), together providing a more comprehensive assessment. However, some metrics were unavailable due to platform limitations: (1) TikTok did not publicly display total view counts for certain videos; and (2) YouTube did not provide public counts for “collections” and "shares." Additionally, collected data included uploader ID, follower counts, verification status, and verification type. These data served as key supplements to the "source and contextual information" dimension; they objectively quantified uploader authority and influence from a platform-mechanism perspective, thereby informing assessments of source reliability and potential reach. Professional or certified individuals were identified according to predefined criteria (Additional File 1). Edited, translated, or duplicated videos were classified as non-original. Video formats varied and included solo narration, Q&A sessions, lecture-slide or classroom recordings, animation or live-action demonstrations, and clinical scenario-based presentations.

Video review and classification

Between February 12 and 14, 2025, two researchers independently reviewed all collected videos and excluded those deemed irrelevant or duplicate (Additional File 1). Guided by the knowledge framework established in SAHS clinical guidelines[25]and considering common narrative patterns and public concerns across platforms, the remaining videos were categorized into the following topic areas: anatomy, pathology, epidemiology, etiology/prevention, symptoms, examinations/diagnosis, and prognosis. Because many videos addressed multiple themes, the number of topics covered per video was recorded. Videos that did not fall into any of the above categories were excluded. These primarily included: personal illness narratives lacking substantive medical information; videos that only demonstrated device unboxing or operation (e.g., ventilators) without explaining their relevance to SAHS treatment; and general popular-science videos focusing solely on snoring or other sleep problems unrelated to SAHS.

Video quality assessment

Video characteristics were systematically documented, and uploader types and content categories were independently classified by two reviewers. Between March 6 and March 9, 2025, two respiratory disease specialists conducted double-blinded quality assessments using five validated instruments: the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT), the Video Information Quality Index (VIQI), the Global Quality Score (GQS), the JAMA benchmark criteria, and the modified DISCERN instrument (mDISCERN). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or adjudication by a senior expert. All three respiratory specialists had more than ten years of clinical experience and were actively involved in health education, including publishing articles, producing educational videos, and delivering community-based health education. Reliability analysis was performed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ). Interpretation followed conventional thresholds: κ > 0.8 indicated excellent agreement, 0.6–0.8 good agreement, 0.4–0.6 moderate agreement, and ≤ 0.4 poor agreement26. The overall inter-rater agreement for video classification and quality scoring was excellent (Cohen’s κ = 0.81).

The selection of multiple instruments was conceptually motivated by the Information Quality (IQ) framework proposed by Wang and Strong, which emphasizes that information quality is multidimensional27. We selected these five instruments to achieve a complementary, multidimensional assessment of video quality and to avoid the limitations of any single metric. Each instrument provided a distinct perspective: mDISCERN assessed information credibility28; GQS evaluated overall production quality29; VIQI offered a multidimensional appraisal of content quality21; the JAMA benchmark assessed scientific accuracy and clinical relevance30; and PEMAT evaluated understandability and actionability of patient education materials31 (see Additional File 2). This approach minimizes construct underrepresentation, a common limitation in single-tool quality assessments. Importantly, these instruments have been validated in multiple international studies and are widely applied to evaluate health-related social media content, demonstrating acceptable reliability in this context21,28,29,30,31. Retaining independent scores for these five instruments constituted a core methodological design of this study, intended to decompose the complex construct of “video quality” and address reviewers’ concerns about redundancy. These instruments were considered complementary rather than redundant, each measuring distinct dimensions that may diverge in public-health communication: scientific accuracy (JAMA) assessed medical correctness; information credibility (mDISCERN) evaluated transparency of content production (e.g., disclosure of sources or conflicts); public usability (PEMAT) assessed understandability and actionability for lay audiences; and production quality (GQS) evaluated audiovisual execution and flow. VIQI served as an integrative reference measure. Maintaining the independence of these dimensions was important. For example, a video could be scientifically inaccurate (low JAMA score) yet display high production and usability scores (GQS and PEMAT), thereby appearing authoritative. Collapsing all metrics into a single composite index (as suggested by one reviewer) would obscure such discrepancies. Accordingly, the multidimensional instrument set was chosen to empirically reveal potential divergence between “surface quality” (e.g., production values and clarity) and “core quality” (e.g., scientific accuracy and credibility).

Statistical analysis

Normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Given that distributions were non-normal, descriptive statistics were reported as medians (min–max) with interquartile ranges [IQR] (P25, P75). Group comparisons for non-normally distributed continuous variables were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test; reported results included the test statistic (U) and effect size (r). For categorical variables, analyses used chi-square tests; reported results included the test statistic (χ2), degrees of freedom (df), and effect size (Cramér's V). Continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test was applied when appropriate. Detailed statistical comparisons for all group analyses, including effect sizes, were provided in Additional File 3.

To mitigate inflation of Type I error rates associated with multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was applied. Consequently, for platform-wise comparisons, the significance threshold was adjusted to p < 0.0167 (0.05/3 comparisons). The alpha level for the correlation matrix was similarly adjusted according to the number of tests performed per platform.

Bivariate correlations were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, which also served as a measure of effect size. To account for potential confounding variables beyond bivariate analyses, multivariate linear regression models were constructed. The regression models were constructed to empirically test the theoretical premise that content credibility is driven primarily by uploader identity rather than engagement metrics. Acknowledging the cross-sectional design, these findings are interpreted as theoretically consistent associations rather than causal mechanisms. The models aimed to determine whether associations observed in the bivariate analysis persisted after controlling for key covariates: video length (s), duration (days), and uploader type (professional vs. non-professional). Drawing on principles of external validation32, independent models were developed for each platform to evaluate the cross-ecological robustness of these quality determinants.

To reduce multicollinearity and multiple-comparison artifacts, VIQI was selected as the primary dependent variable (Y), as it represented the most comprehensive measure of overall video quality among the five instruments. Separate models were run for each platform, with available audience interaction metrics (e.g., views, thumbs-up) entered as simultaneous predictors. Regression model results were reported as unstandardized coefficients (B) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and p-values. For all statistical tests, a two-sided p-value below the corrected threshold was considered indicative of statistical significance. All data analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.2).

Collectively, the selection of these instruments constitutes a theory-driven measurement strategy, mapping distinct dimensions of video quality onto established constructs in information science: credibility, accuracy, usability, and technical fidelity. This alignment ensures that the operationalization of “quality” is conceptually robust and grounded in established paradigms of information behavior and digital health communication.

Result

A total of 903 videos were initially collected across the three platforms. After screening, 227 videos met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). All videos were presented in either Chinese or English, and some provided bilingual subtitles. According to the Shapiro–Wilk test, all continuous variables were non-normally distributed.

Video features

TikTok videos were considerably shorter than those on YouTube and Bilibili, with a median duration of 39 s (IQR: 19.5–73), compared with 167 s (IQR: 99–376) on YouTube and 237 s (IQR: 91–377) on Bilibili (Table 1, Fig. 2). Detailed statistical results and effect sizes are provided in Additional File 3. In terms of engagement, TikTok videos received the highest numbers of likes and comments. Although Bilibili offered a wider range of interactive features (e.g. community design), its absolute engagement metrics were lower than those of TikTok.

Uploader characteristics

Across the three platforms, 32 certified uploaders were identified on YouTube, 62 on Bilibili, and 72 on TikTok (Table 2, Fig. 3A). The distribution of uploader types varied significantly across platform. On YouTube, non-profit organizations contributed the largest proportion of content (36.4%), whereas physicians accounted for the majority on Bilibili (72.6%) and TikTok (76.4%). Notably, seven certified TCM practitioners were identified among Bilibili uploaders. Compared with TikTok, Bilibili uploaders posted more frequently, indicating greater consistency in content production.

Content categories and forms

Most videos were original productions, with YouTube and TikTok showing particularly high originality rates (94.3% and 94.9%, respectively), while Bilibili showed a slightly lower rate (78.4%) (Table 3, Fig. 3C). Longer videos on YouTube and Bilibili typically addressed a broader range of topics, whereas shorter TikTok videos tended to focus on fewer themes. Across platforms, symptoms were the most commonly discussed topic. The most commonly recommended therapies involved lifestyle adjustments, such as quitting smoking and drinking, changing sleeping positions, and losing weight. These lifestyle changes were repeatedly emphasized in numerous videos. However, thematic emphasis differed: YouTube content more often included anatomy and pathology, while Bilibili and TikTok concentrated on etiology, prevention, and treatment. In terms of presentation styles, solo narration was dominant on YouTube, whereas Q&A formats were most frequently employed on TikTok and Bilibili. Additionally, scenario-based medical videos appeared more frequently on TikTok (Fig. 3B).

Video quality assessment

Inter-rater reliability was excellent (Cohen’s κ = 0.81). As shown in Table 4 and Fig. 4A, YouTube videos achieved significantly higher VIQI, GQS, and mDISCERN scores compared with those on TikTok and Bilibili (p < 0.05). YouTube also received the highest PEMAT-U scores. After Bonferroni correction, no statistically significant difference was observed in PEMAT-A scores between YouTube and Bilibili (p = 0.030). TikTok and Bilibili generally received similar scores. Interestingly, in some cases, videos created by laypersons received quality scores that exceeded those of professional creators (Table 5, Fig. 4B).

Relevance analysis

The initial Spearman correlation analysis (Table 6), after Bonferroni correction, revealed a clear lack of association between video quality and audience engagement. Almost all previously observed weak-to-moderate correlations became non-significant. This indicates that informational quality is not a primary driver of audience interaction on these platforms. Only a few correlations remained statistically significant after correction: on YouTube, views remained strongly positively correlated with VIQI-sum (p < 0.001), and on TikTok, thumbs-up and collections were also significantly correlated with VIQI-sum (both p < 0.001). However, scientific accuracy and credibility metrics (e.g., mDISCERN, JAMA) showed no significant correlations with any engagement metrics on any platform. Furthermore, to address the concern that even these few remaining correlations (Table 6) might be the result of confounding variables, we constructed the multivariate linear regression models described in the methods section. As specified, we used VIQI-sum as the primary dependent variable.The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 7. After controlling for video length, time since upload, and uploader type, all audience engagement metrics (e.g., views, thumbs-up, collections) lost their statistically significant associations with VIQI-sum scores (all p > 0.05). This finding suggests that the correlations in Table 6 were likely driven by confounding factors rather than a direct association between video quality and audience engagement. Notably, professional uploader status (is_Professional) was a significant predictor of higher video quality on both Bilibili and TikTok (p < 0.01), indicating that uploader identity, rather than audience engagement, is a more reliable indicator of video quality.

Discussion

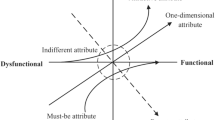

Analyzing SAHS-related content across YouTube, Bilibili, and TikTok, this study reveals distinct platform-specific disparities. Collectively, these variances are elucidated by our "Platform-Cognition-Trust" triadic framework, which synthesizes algorithmic curation, cognitive heuristics, and trust dynamics33. Algorithmic architectures structure information dissemination by prioritizing content that provokes immediate interaction34. Within this environment, users default to peripheral cues—such as audio-visual fidelity—for rapid judgment, precipitating a structural decoupling between user engagement and medical substance18. This cognitive processing reshapes trust formation in digital spaces: credibility becomes increasingly contingent on interface elements like high production values and narrative fluency, while the authority of traditional professional credentials is disproportionately marginalized19. Conceptually, this study advances existing literature by demonstrating that information quality, visibility, and perceived trustworthiness are not isolated metrics but interdependent outcomes governed by platform architecture. Rather than treating quality and engagement as distinct descriptive phenomena, this framework offers a unified analytical lens. It provides a mechanistic explanation for why evidence-based medical content struggles for visibility within the constraints of the algorithmic attention economy. To further clarify this theoretical contribution, we have added a conceptual figure (Fig. 5) in the Discussion section that visually maps the interactions between platform algorithms, user cognitive heuristics, and trust formation.

From this theoretical vantage point, Bilibili represents a unique hybrid media ecology, fusing the depth of long-form education with the high-frequency feedback loops of short-video entertainment13. This structural hybridity elucidates its intermediate standing in both information quality and engagement metrics. Contrary to prior classifications of Bilibili as merely a "long-video platform"12,13, our findings suggest its algorithmic and community architectures foster a distinct communication logic—one that synthesizes professionalism with entertainment, thereby sustaining a dynamic equilibrium between quality and engagement. The observed cross-platform disparities further corroborate the “hypernudge” paradigm, which frames algorithmic interfaces as adaptive environments that systematically steer user attention16. Within this framework, visibility is not merely a function of engagement statistics but is actively engineered by the interplay between user cognition and specific design affordances—such as swipe mechanics, feed density, and temporal pacing35. These sociotechnical dynamics clarify why specific narrative formats systematically secure visibility dominance, often independent of—or even decoupled from—their medical accuracy36.

From a user perspective, the disconnect between engagement and quality elucidates critical cognitive disparities and decision-making biases. There are systematic differences in information processing and judgment among individuals with different professional backgrounds, which may be further solidified into cognitive path dependence under the reinforcement of algorithm recommendation37. Compounded by cognitive load, low digital health literacy promotes heuristic processing38. These cognitive shortcuts are exacerbated by fast-swipe interfaces, which encourage rapid, low-effort evaluation39,40. This creates a feedback loop where engagement-driven algorithms prioritize “consumable” narratives over clinically robust information40.

Consequently, users effectively adapt their cognitive models to align with algorithmic logic. As algorithms promote emotional, simplified content consistent with "platform-based narratives"41, users increasingly defer to external cues—such as production quality and popularity metrics—for credibility judgments. Analogous to clinicians using AI to reduce cognitive burden in complex diagnoses42, social media users engage in "algorithm-assisted cognitive offloading." By shifting validation tasks to platform recommendation mechanisms, users effectively outsource critical appraisal. This outsourcing fosters a superficial understanding of conditions like SAHS. Users become prone to adopting intuitive, algorithmically promoted solutions, potentially delaying or replacing necessary professional medical assessments14.

Furthermore, platform-level divergence is rooted in distinct architectural logics. YouTube’s search-oriented, long-form environment facilitates systematic information processing, supporting content with higher informational density43. Conversely, TikTok’s fast-swipe interface encourages heuristic processing, rewarding content optimized for entertainment value, aesthetic immediacy, and emotional resonance36,39. Bilibili, occupying a hybrid structural position, exhibits affordances of both ecosystems, resulting in intermediate patterns of quality and engagement12,13. These structural differences provide a theoretically grounded explanation for the platform-level disparities in content quality and visibility observed in this study.

Our finding that some non-professional videos received high scores can be explained by trust-formation models19,22. In digital ecosystems, users prioritize peripheral cues—such as narrative fluency and visual design—over the systematic verification of medical accuracy44,45. Non-professionals effectively leverage these strategies to establish credibility44. Furthermore, algorithms that reward watch-time and engagement amplify this dynamic, reinforcing the primacy of presentation quality over scientific rigor40. These patterns demonstrate that digital credibility is not exclusively knowledge-based but is sociotechnically constructed46. Features such as narrative fluency, production polish, and alignment with platform-native aesthetics act as “credibility proxies,” allowing non-professional creators to achieve perceived authority despite lacking formal training47. This aligns with theories of distributed trust, which posit that authority in digital environments is negotiated through interface cues and performative signals rather than traditional institutional credentials48.

This study contributes a multi-dimensional analysis to the literature. Notably, the marginalization of TCM content reflects a structural misalignment between TCM’s holistic, context-dependent epistemology and the algorithmic preference for reductionist, visually explicit biomedical cues13,21. This observation illustrates how distinct medical knowledge systems encounter structural barriers within algorithmic architectures, introducing a critical cultural dimension to the "quality-engagement" gap49. Consequently, there is an urgent need for culturally responsive strategies that translate TCM frameworks into formats compatible with algorithmic logic. This approach aims to enhance accessibility within visually driven environments without compromising the conceptual integrity of TCM21.

These findings suggest that the synergistic shaping of user engagement, content credibility, and information dissemination under a unified socio-technical mechanism can generate multi-level significant value. The robust correlation between professional identity and content quality, confirmed by our regression models, provides an empirical basis for constructing effective health communication strategies. For medical professionals, training in digital narrative strategies is crucial. Mastering these skills facilitates the delivery of credible content, thereby enhancing the algorithmic visibility and societal influence of professional discourse19,50. For platforms, we propose a "dual-track" recommendation mechanism. By integrating verified professional credentials as auxiliary algorithmic weights, platforms can create a bias correction system that balances engagement metrics with content credibility51,52. Furthermore, public health institutions and professional societies must collaborate with platforms to establish standardized content certification systems and production guidelines. Such governance is essential to systematically improve the identification and dissemination of high-quality health information53,54.

Limitations

First, the restriction of our sample to the top 100 search-ranked videos introduces inherent selection bias. While this approach mimics typical user behavior, popularity-driven sorting may not represent the full spectrum of available content, potentially skewing estimates of average information quality by excluding the “long tail” of less visible content11. Additionally, given the opacity of personalized ranking algorithms, the sampled dataset may reflect embedded visibility biases that privilege specific uploader profiles, linguistic communities, or presentation formats16. While unavoidable in search-simulation designs, these constraints highlight the need for future research utilizing API-level data or user-centered experiments to capture a more ecologically comprehensive representation of content exposure35.

Second, regarding instrumentation, while multiple validated tools were employed to ensure construct validity, quality assessments remain constrained by the epistemological frameworks embedded within these instruments. Specifically, while we rigorously assessed scientific accuracy, current metrics may fail to capture the affective nuance of patient-centric narratives, which can hold therapeutic value despite lower technical scores44.

Third, the exclusion of qualitative metadata, such as user comments and sentiment analysis, limits our insight into audience interpretation and emotional reception55. This omission restricts granular analysis of how specific features drive engagement36. However, as the primary outcome was expert-rated informational quality rather than user reception, this limitation does not compromise the internal validity of the quality assessment.

Fourth, our analysis is linguistically confined to Chinese and English content within specific platform ecosystems. Consequently, the generalizability of these findings to regions with distinct digital infrastructures or medical cultures remains limited24.

Finally, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Since algorithmic inputs (e.g., user history) remain inaccessible, engagement metrics serve as proxies for visibility rather than direct indicators of algorithmic preference. Thus, observed associations should be interpreted as structural patterns rather than causal mechanisms.

Conclusions

This study conducted a cross-sectional analysis of SAHS-related videos across three major online video platforms. The analysis incorporated both Chinese- and English-language content and applied five standardized instruments (PEMAT, VIQI, GQS, JAMA, and mDISCERN) to evaluate video information quality from multiple dimensions. Additionally, this study examined the representation of TCM within SAHS-related content across platforms. These findings provide descriptive evidence regarding the current landscape of SAHS-related video content on major social media platforms. The findings may inform platform administrators, content creators, and public health educators. Long-form platforms (e.g., YouTube, Bilibili) tended to provide more detailed content but had lower engagement, while short-form platforms (e.g., TikTok) achieved higher engagement but generally featured less comprehensive information. Among the three platforms, YouTube showed the highest average quality scores; however, overall quality still varied substantially. Some non-professional creators appeared to use platform-adapted visual and narrative strategies that enhanced perceived credibility, regardless of formal medical expertise.

To improve accessibility, high-quality educational content could be adapted and disseminated across platforms. In conclusion, the study highlights differences across platforms in how SAHS-related information is produced, presented, and engaged with. Efforts to align engagement with scientific accuracy may involve adjustments to platform recommendation systems, enhanced communication training for healthcare professionals, and supportive regulatory frameworks. Integrating perspectives from both Western medicine and TCM may help diversify health communication approaches. Coordinated efforts across platforms, healthcare professionals, and public health agencies may support more effective dissemination of accurate and comprehensible SAHS-related information. Beyond empirical comparison, this study offers a theoretically informed account of how informational, cultural, and algorithmic forces jointly shape the visibility and credibility of SAHS-related content across major social media ecosystems.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data analyzed in this study, such as video content, user reviews, publicly available metadata, etc., comes from the following publicly available online video platforms. The website is as follows: [https://www.youtube.com]; [https://www.bilibili.com]; [https://www.douyin.com] .

Abbreviations

- VIQI:

-

Video information and quality index

- mDISCERN:

-

Modified DISCERN

- GQS:

-

Global quality score

- PEMAT:

-

Patient education materials assessment tool

- JAMA:

-

The journal of the American medical association

- SAHS:

-

Sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome

- TCM:

-

Traditional Chinese medicine

- COVID-19:

-

Corona virus disease 2019

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Q&A:

-

Question and answer

- HSM:

-

Heuristic-systematic model

- IQ:

-

Information quality

- AI:

-

Artificial intelligence

References

Alvarez-Estevez, D. & Moret-Bonillo, V. Computer-Assisted Diagnosis of the Sleep Apnea-Hypopnea Syndrome: A Review. Sleep Disord. 2015, 237878 (2015).

Woodward, S. H. & Benca, R. M. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Psychiatric Disorders. JAMA Netw Open 7, e2416325 (2024).

Tian, J., Zhang, Y. & Chen, B. Sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome and liver injury. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 123, 89–94 (2010).

Battaglia, E. et al. Unmasking the Complex Interplay of Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome, Heart Failure, and Sleep Dysfunction: A Physiological and Psychological Perspective in a Digital Health World. Behavioral Sciences 15, (2025).

Peppard, P. E. et al. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 177, 1006–1014 (2013).

Punjabi, N. M. et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and mortality: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 6, e1000132 (2009).

Grosberg, D., Grinvald, H., Reuveni, H. & Magnezi, R. Frequent Surfing on Social Health Networks is Associated With Increased Knowledge and Patient Health Activation. J. Med. Internet Res. 18, e212 (2016).

Song, S. et al. Short-Video Apps as a Health Information Source for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Information Quality Assessment of TikTok Videos. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e28318 (2021).

Ostrovsky, A. M. & Chen, J. R. TikTok and Its Role in COVID-19 Information Propagation. J. Adolesc. Health 67, 730 (2020).

McLoughlin, K. L. & Brady, W. J. Human-algorithm interactions help explain the spread of misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 56, 101770 (2024).

Cinelli, M. et al. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Sci. Rep. 10, 16598 (2020).

Zhu, W. et al. Information quality of videos related to esophageal cancer on tiktok, kwai, and bilibili: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 25, 2245 (2025).

Zeng, F. et al. Douyin and Bilibili as sources of information on lung cancer in China through assessment and analysis of the content and quality. Sci. Rep. 14, 20604 (2024).

Rhee, J., Iansavitchene, A., Mannala, S., Graham, M. E. & Rotenberg, B. Breaking social media fads and uncovering the safety and efficacy of mouth taping in patients with mouth breathing, sleep disordered breathing, or obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 20, e0323643 (2025).

Niu, Z. et al. Quality of Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Videos Available on TikTok and Bilibili: Content Analysis. JMIR Form Res 8, e60033 (2024).

Yeung, K. ‘Hypernudge’: Big Data as a mode of regulation by design. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20, 118–136 (2017).

Kloth, S. et al. The Relevance of Algorithms. MIT Press (2014).

Metzger, M. J. Making sense of credibility on the Web: Models for evaluating online information and recommendations for future research. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 58, 2078–2091 (2007).

Salaschek, M. & Bonfadelli, H. Digital health communication and factors of influence. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 63, 160–165 (2020).

Kaptchuk, T. J. Chinese Medicine: The Web That Has No Weaver. Rider (1985).

Liu, Z. et al. YouTube/ Bilibili/ TikTok videos as sources of medical information on laryngeal carcinoma: cross-sectional content analysis study. BMC Public Health 24, 1594 (2024).

Walther, J. B. Computer-Mediated Communication: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal Interaction. Commun. Res. 23, 3–43 (1996).

Pourreza, M. & Ensan, F. Towards semantic-driven boolean query formalization for biomedical systematic literature reviews. Int. J. Med. Informatics 170, 104928 (2023).

Wu, H. et al. Comparative analysis of NAFLD-related health videos on TikTok: a cross-language study in the USA and China. BMC Public Health 24, 3375 (2024).

Chinese Thoracic Society. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of adult obstructive sleep apnea: a protocol. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 48, 701–707 (2025).

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb) 22, 276–282 (2012).

Wang, R. Y. & Strong, D. M. Beyond accuracy: What data quality means to data consumers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 12, 5–33 (1996).

Charnock, D., Shepperd, S., Needham, G. & Gann, R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol. Commun. Health 53, 105–111 (1999).

Bernard, A. et al. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the World Wide Web. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 102, 2070–2077 (2007).

Yeung, A., Ng, E. & Abi-Jaoude, E. TikTok and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study of Social Media Content Quality. Can. J. Psychiatry 67, 899–906 (2022).

Shoemaker, S. J., Wolf, M. S. & Brach, C. Development of the Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ. Couns. 96, 395–403 (2014).

Abrantes, J., Bento e Silva, M. J. N., Meneses, J. P., Oliveira, C., Calisto, R. W. F. M. Filice, G. F. External validation of a deep learning model for breast density classification. ECR 2023 C-16014, (2023).

Orlikowski, W. J. Sociomaterial Practices: Exploring Technology at Work. Organ. Stud. 28, 1435–1448 (2007).

Metzler, H. & Garcia, D. Social Drivers and Algorithmic Mechanisms on Digital Media. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 19, 735–748 (2024).

O’Brien, H. L., Davoudi, N. & Nelson, M. TikTok as information space: A scoping review of information behavior on TikTok. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 47, 101379 (2025).

Paek, H.-J., Kim, K. & Hove, T. Content analysis of antismoking videos on YouTube: message sensation value, message appeals, and their relationships with viewer responses. Health Educ. Res. 25, 1085–1099 (2010).

Calisto, F. M. et al. Assertiveness-based Agent Communication for a Personalized Medicine on Medical Imaging Diagnosis. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 35,80682 (2023)

Xie, W., Kang, C., Xu, L., Cheng, H. & Dai, P. Study on the quality evaluation of mobile social media health information and the relationship with health information dissemination. Inform. Manag. 61, 103927 (2024).

Qi, S., Chen, Q., Liang, J., Yang, X. & Li, X. Evaluating the quality and reliability of cervical cancer related videos on YouTube, Bilibili, and Tiktok: a cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health 25, 3682 (2025).

Gao, Y., Liu, F. & Gao, L. Echo chamber effects on short video platforms. Sci. Rep. 13, 6282 (2023).

Ge, R. et al. The Quality and Reliability of Online Videos as an Information Source of Public Health Education for Stroke Prevention in Mainland China: Electronic Media-Based Cross-Sectional Study. JMIR Infodemiol. 5, e64891 (2025).

Calisto, F. M., Abrantes, J. M., Santiago, C., Nunes, N. J. & Nascimento, J. C. Personalized explanations for clinician-AI interaction in breast imaging diagnosis by adapting communication to expertise levels. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 197, (2025).

Helming, A. G., Adler, D. S., Keltner, C., Igelman, A. D. & Woodworth, G. E. The Content Quality of YouTube Videos for Professional Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Acad. Med. 96, 1484–1493 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Assessing the content and quality of GI bleeding information on Bilibili, TikTok, and YouTube: a cross-sectional study. Sci. Rep. 15, 14856 (2025).

Aktas, B. K. et al. YouTube™ as a source of information on prostatitis: a quality and reliability analysis. Int J Impot Res 36, 242–247 (2024).

Suarez-Lledo, V. & Alvarez-Galvez, J. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e17187 (2021).

Metzger, M. J. & Flanagin, A. J. Credibility and trust of information in online environments: The use of cognitive heuristics. J. Pragmat. 59, 210–220 (2013).

Kridera, S., Kanavos, A., Kridera, S. & Kanavos, A. Exploring Trust Dynamics in Online Social Networks: A Social Network Analysis Perspective. Mathematical and Computational Applications 29, (2024).

Striphas, T. Algorithmic culture. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 18, 395–412 (2015).

He, F. et al. Quality and reliability of pediatric pneumonia related short videos on mainstream platforms: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 25, 1896 (2025).

Ottewill, C., Gleeson, M., Kerr, P., Hale, E. M. & Costello, R. W. Digital health delivery in respiratory medicine: adjunct, replacement or cause for division?. Eu. Respir. Rev 33, 230251 (2024).

Serrano-Guerrero, J., Romero, F. P. & Olivas, J. A. A relevance and quality-based ranking algorithm applied to evidence-based medicine. Comput. Methods Programs. Biomed. 191, 105415 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. The quality and reliability of short videos about thyroid nodules on BiliBili and TikTok: Cross-sectional study. Digit. Health 10, 20552076241288830 (2024).

Wang, L., Chen, Y., Zhao, D., Xu, T. & Hua, F. Quality and dissemination of uterine fibroid health information on tiktok and bilibili: cross-sectional study. JMIR Form. Res. 9, e75120 (2025).

Li, H., Cheng, X. & Liu, J. Understanding Video Sharing Propagation in Social Networks: Measurement and Analysis. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 10, (2014).

Acknowledgements

We express their gratitude to everyone who posted the videos on the three platforms.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Laboratory of TCM Pulmonary Science of Jiangxi Province (No.2024SSY06321), the Key Research and Development Project of Jiangxi Province, the field of Social Development, the development and application of the Yin-Yang Attribute Breath Recognition Instrument for chronic obstructive pulmonary Disease (20232BBG70021), the Fifth Batch of National Traditional Chinese Medicine Excellent Clinical Talents Training Project. (Announcement from the Personnel and Education Department of the National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. No. 2022-1)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Q. and Y.Z. contributed equally to conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation. T.Y. contributed to data curation, investigation, validation, and writing—review & editing. Q.W. contributed to data curation, investigation, and software. Z.Z. contributed to data curation and investigation. L.W. contributed to funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, and writing—review & editing. Z.D. contributed to resources, supervision, validation, and writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the final submitted manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study exclusively analyzed publicly available data from online platforms. All data was collected and analyzed in an anonymized manner, and no human subjects were directly involved. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, X., Zhou, Y., Yuan, T. et al. A cross-sectional analysis of the quality and characteristics of sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome videos on YouTube, Bilibili, and TikTok. Sci Rep 16, 4070 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34182-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34182-1