Abstract

Recurrent implantation failure (RIF) occurs in 10–15% of IVF cycles with evidence from a few randomized control trials (RCTs) that local endometrial injury (LEI) leads to higher live birth rates whose exact mechanism is currently unknown. During the implantation period, modulation in immune milieu occur in tandem with profound morphologic and functional changes in the endometrium. The landscape of immune cells in the endometrium in pre- and post-LEI in RIF is currently unknown. Thirty-seven women with RIF (age 34.6 ± 3.3 years old) underwent LEI by two sequential mid-luteal phase endometrial biopsies prior to embryo transfer. To characterize the immunological landscape alterations in LEI, we performed immunophenotypic assessment with flow cytometry to provide insights into the basal (first biopsy) and altered (second biopsy) biology of dendritic cells (DC), macrophages, natural killer (NK), T and B cells in the RIF population before and after LEI. Clinical pregnancies occurred in seventeen women (46%). Among analysed immune cells, T (34.6%) and NK cells (26.2%) predominate in the mid-luteal endometrium. A consistent increase in lymphocytes and decrease in antigen presenting cells (APCs) were observed between the two biopsies although not statistically significant. Interrogation of the immune milieu in patients who either fell pregnant or not did not show any differences once cases with endometriosis were taken out of the analyses. There were no further difference in any of the other measured immune cell subsets between the first and second endometrial biopsy. We found limited changes in the immune cell compartments after LEI. Further research with higher resolution methods may provide more information on the effects of LEI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advancements in reproductive techniques have improved the live birth rates of in-vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles. However, live-birth rates of IVF have plateaued around 30%1 for over a decade despite extensive research into embryonic factors and endometrial receptivity2,3,4. Embryo implantation5 remains the rate limiting step in IVF especially in a small group of women with recurrent implantation failure (RIF). The definition of RIF is currently not universally defined. Proposed RIF definitions include failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after transferring at least four good quality embryos following two to six embryo-transfers (ET)6,7,8,9.

It was previously observed that local endometrial injury (LEI) by endometrial scratching before IVF led to a two-fold increase in pregnancy rates10,11. Endometrial scratch involves obtaining tissue biopsy using a sampler such as a Pipelle catheter where a ‘scratch’ is performed that is reasonably well tolerated without any need for analgesia12. Since then, there have been many randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of LEI on pregnancy rates prior to IVF13,14,15,16. In the presence of inconclusive and contrasting evidence, there is no current consensus whether patients should receive endometrial scratching prior to IVF17. The majority of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed a general trend towards benefit of LEI especially where the number of previous failures are more than two. In order to improve the power to detect possible differences, meta-analyses conducted by both Vitagliano et al. and van Hoogenhuijze et al. both demonstrated improved live-birth rates post LEI in women with multiple failures18,19. One RCT that stood out was the PIP trial that did not show a benefit in a subgroup of women with two or more failures20. However, the PIP trial was designed to test the effect of LEI in a unselected group of patients and not women with RIF. The most recent large RCT, SCRaTCH trial, showed a trend towards benefit after one IVF cycle failure and with a single luteal phase LEI21. A more updated meta-analyses provided by Vitagliano et al. that included both the PIP and SCRaTCH trial continued to show a benefit of Live Births (RR 1.21, 95CI 1.05–1.40)21. The timing, frequency and type of LEI instituted varied considerably between the various studies, making it difficult to generalize the findings14,19,22. It is therefore important and timely to define the type of patients being offered this intervention, the way LEI is administered in this specific group of patients with RIF to maximize their chances of getting pregnant.

Putative mechanisms on how LEI may improve implantation rates in patients with RIF are currently unknown. Some proposed mechanisms include increasing endometrial receptivity by altering decidualization favouring implantation23, provoking the endometrial immune system to generate an inflammatory response24 leading to increased secreted cytokines, growth factors and upregulation of adhesion molecules24,25,26. The feto-maternal immune cross talk is complex with recruitment and modification of endometrial immune cells involved in implantation27. Research into the immune milieu in the endometrium have shown that the roles of decidual immune cells are associated closely with implantation, angiogenesis and maintenance of pregnancy28,29. These include macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, lymphocytes such as B cells and T cells which are involved with implantation and feto-maternal tolerance towards pregnancy5,30,31.

We have previously studied the effect of LEI on SUSD2 + mesenchymal stromal cells using a sequential mid-luteal Pipelle approach23. However, the effects on the various subsets of immune and APCs in subsequent menstrual cycles are unknown. To date, there has been no properly performed study that characterizes tissue resident immune cell sub-sets before and after LEI in subsequent luteal phase in women with RIF, and how any alterations in immune cell types and compositions relate to pregnancy outcomes. Here, we performed a sequential LEI in women with well-defined RIF to characterise the immune cell landscape within the endometrium through a multi-parameter flow cytometry panel that was designed to allow us to identify DC subsets; CD141 + DC and CD1c + DC (also known as DC1 and DC2, respectively), plasmacytoid DC (pDC), CD14 + macrophages, CD3 + T cells and CD56 + NK cells32. The aims of our study are to firstly, establish the endometrial immune milieu by interrogating composition and changes of immune cell subtypes before and after LEI in subsequent luteal phase cycles in women with RIF and secondly, to address any relationship between alterations in endometrial immune landscape and pregnancy after LEI.

Results

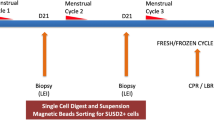

Fifty-three women with RIF were recruited of which 16 women were excluded due to poor quality samples or failure to return for a repeat endometrial biopsy. Thirty seven women (age 34.6 ± 3.3 years old) underwent two sequential mid-luteal phases endometrial Pipelle biopsies prior to embryo-transfer (ET) (Fig. 1). 81% of these females were ovulatory and 65% of these women had primary infertility of which majority (57%) have unknown reasons i.e. not attributable to various reasons as indicated in Table 1. Thirty-three women (88%) had 2–3 IVF cycles, and the remaining 4 women had ≥4 IVF cycles with an average of 4.9 ± 1.7 previous embryo transfers (Table 2). Seventeen women (17/37, 46%) had successful implantation indicated by an elevated βhCG result of > 25 mIU per milliliter post IVF after the second LEI. Among these 17 women, there were 1 biochemical pregnancy, 3 miscarriages and 13 live births (35.1%).

Immunophenotypic assessment providing insights into the populations of DCs, macrophages, NK, B and T cells in the endometrium of the RIF population by flow cytometry (Fig. 2) was analysed before(1st LEI) and after the LEI (2nd LEI) procedure (Fig. 3). In the biopsies obtained, T-cells were the predominant immune cell (34.6 ± 19.9%@1st LEI and 40.2 ± 22.2@2nd LEI), followed by NK cells (26.2 ± 17.5% at 1 st LEI and 29.1 ± 18.0% at 2nd LEI), CD14 + macrophages (7.5 ± 8.1% at 1 st LEI and 7.2 ± 8.5% at 2nd LEI), B cells (2.4 ± 1.7% at 1 st LEI and 3.6 ± 2.2% at 2nd LEI, CD141 + DCs (1.3 ± 1.0% at 1 st LEI and 1.0 ± 0.9% at 2nd LEI and CD1c + DCs (0.8 ± 0.7% at 1 st LEI and 0.6 ± 0.6% at 2nd LEI (Fig. 3A). No significant differences were observed in the various cell types in all the paired samples we obtained (p-value:0.26 (T-cells), 0.40 (NK cells), 0.84 (CD14 + macrophages), 0.25 (B cells), 0.07 (CD141 + DCs) and 0.36 (CD1c + DCs) (Fig. 3B-G). We did see a consistent upward trend with the lymphocytes (T, NK and B cells) and a consistent downward trend with the APCs between the 1 st and 2nd LEI biopsies (Fig. 3). In our cohort where mid-luteal progesterone levels were available (n = 27), 15 women have evidence of ovulation at both cycles of LEI, while 12 women ovulated only in one cycle or not at all. As anovulatory patients may not have a physiological luteal phase, we segregate our population and analyse the immune cell proportions in the 2 groups separately and we did not find any differences in the immune cell milieu of both the ovulatory and anovulatory patients cohort post an LEI.

Flow cytometric gating strategy used to identify mononuclear phagocyte and lymphocyte populations. Live cells (DAPI−) were first selected. Doublets were removed and leukocytes (CD45+) were identified (A). Mononuclear phagocytes were identified as HLA-DR+ and lineage (CD3, CD19, CD20)−. pDC and DC are CD14− and CD16−. pDC are CD123+ and CD11c−. CD141+DC are CD1c−. CD1c+ DC are CD141− (Fig. 2Ai). T cells express CD3. B cells express CD19 and CD20. NK cells express CD56 (Fig. 2Aii). Representative histograms used to further characterise the cellular populations, from n = 1–3 experiments (B). CD14+ macrophages also express CD163, CD64, SIRPα/β and CD86(Fig. 2B). Fluorescence minus one (FMO) – negative control.

Segregating the samples based on eventual pregnant outcomes, pregnant women were younger than the non-pregnant group though not statistically significant (32.3 ± 8.1 vs. 35.0 ± 3.7, p = 0.51). The proportion of the different immune cell types for the group of participants with and without a positive pregnancy outcome at the first LEI were all non-significant, indicating similarly comparable immune component prior to LEI. We next investigated if the LEI altered the immune cell milieu by comparing the cellular composition between the first and second LEI in the two groups (non-pregnant and pregnant). There was an increase in T cells in the non-pregnant participants (31.8 ± 21.7 to 44.0 ± 18.3, p-value:0.03) between the 2 LEI which was not observed in the pregnant participants (38.1 ± 19 vs. 35.4 ± 26.2, p-value:0.76, Fig. 4A). Because endometriosis is a potential confounding factor, we repeated the analyses after removing the data of three participants with endometriosis. The resulting p-value was 0.08, suggesting that both the LEI procedure and the presence of endometriosis contributed to this increase in T cells post an LEI. There were no differences between the T-cell proportions at 2nd LEI for the pregnant vs. non-pregnant groups (35.4 ± 26.2 vs. 44 ± 18.3, p-value:0.29). For NK cells, there is a slight increase in the non-pregnant participants (26.25 ± 17.75 to 29.15 ± 18.04, p-value:0.40, Fig. 4B) and a reduction in the pregnant participants (29.02 ± 17.92 to 28.24 ± 19.4, p-value:0.89, Fig. 4C). An opposite trend was observed in the CD14 + macrophages (7.50 ± 8.57 to 5.91 ± 4.56, p-value:0.44 in the non-pregnant group and 7.61 ± 7.77 to 8.89 ± 11.69, p-value:0.63, Fig. 4D). A consistent increase was observed with B cells in both groups (2.06 ± 1.45 to 3.57 ± 3.24, p-value:0.46 in the non-pregnant group and 2.35 ± 2.05 to 3.65 ± 1.70 in the pregnant group, p-value:0.46, Fig. 4E). A consistent decrease was observed with the DCs. The percentage of CD141 + DCs decreased from 1.38 ± 1.08 at first LEI to 0.96 ± 0.79 at second LEI and from 1.18 ± 0.87 to 1.12 ± 1.03 in the non-pregnant (p-value:0.08) and pregnant participants (p-value:0.69) (Fig. 4F) respectively. Similarly, the CD1c + DCs decreased from 0.79 ± 0.74 at first LEI to 0.62 ± 0.61 at second LEI and from 0.75 ± 0.74 to 0.59 ± 0.52 in the non-pregnant (p-value:0.23) and pregnant participants (p-value:0.52)(Fig. 4F) respectively.

Discussion

LEI treatment in the context of RIF, two ET failures or more, has demonstrated some degree of benefit especially in the context of sequential double-luteal phase LEI18,21,33. Here, we took advantage of such a protocol to study the impact of LEI on the immune cell milieu in women with RIF. Our primary finding suggest that there is no change in the composition of T-cells, B-cells, Antigen-Presenting Cells and NK cells using a validated parameter flow panel34. We did however, show an increase in the T-cell population in RIF women who did not become pregnant, within which 2 also suffered from endometriosis.

In our study, seventeen women (46%) had a clinical pregnancy after performing two sequential endometrial scratches prior to IVF. This is consistent with a recent meta-analysis by Vitagliano et al. 2018 which suggested that two luteal phase LEI is the number of interventions that gave a beneficial outcome in women with RIF undergoing IVF18. A meta-analysis involving 2,537 participants showed an improvement in clinical pregnancy rates for participants with 2 or more failed IVF/ICSI cycles back in 201919 and an extension of it by Hoogenhuijze et al., showed in an individual participant data meta-analysis representing 4,112 participants an improved odds ratio of 1.29 of LBR35.

Currently, there is no consensus for the definition of RIF due to the clinical heterogenicity of studies performed. Our selection criteria is consistent with a recent systemic review by Polanski et al. which defined RIF as the absence of implantation after two consecutive cycles of IVF where the cumulative number of transferred embryos was no less than four for cleavage-stage embryos9. A uniform and clear definition of RIF is important as it will aid the counselling and expectation of couples undergoing repeated IVF cycles to achieve a successful pregnancy. In addition, it will clearly define the parameters for which LEI improves pregnancy outcomes as what we have observed in this cohort and our previous study23.

The immune landscape in the endometrium is dynamic with an influx of macrophages, DCs and NK cells during the secretory phase of the menstrual cycle36. The low number of CD45 + cells in the endometrium in the early follicular to early secretory phase undergoes a five-fold increase during the secretory phase37, peaking at the late secretory phase38. Within the innate immune system, uterine NK (uNK) cells and APCs including macrophages and DCs comprise a large proportion of the decidual leukocyte population and they are known to play important roles in modulating trophoblast invasion, inflammation, angiogenesis and vascular remodelling during implantation39,40. Patients with RIF have been shown to have significantly raised NK and B cells41,42, suggesting the presence of a potential differential pro-inflammatory bias in RIF patients.

Unravelling the mechanism behind LEI will also be beneficial in explaining the observable benefits of LEI and in this study, we looked into the immune milieu of the endometrial biopsies for answers. LEI induces an inflammatory response that promotes implantation although its exact mechanism is not elucidated43. In our study, we showed that T-cells were the predominant immune cell, followed by NK cells and CD14 + macrophages in the endometrium of the cohort of RIF patients. This is congruent with Givan et al. where it was established back in 2011 that CD3 + T cells constitutes approximately 40% of the CD45 + cells in the uterine endometrium in both proliferative and secretory phase and estimated the proportion of NK cells to be around 25% of the CD45 + leukocytes44. Flynn et al. however, found that T cells population vary throughout the menstrual cycle, comprise 40–60% of the total leukocyte population in the proliferative phase and drops to < 10% in the late luteal phase in healthy women37. T cells are activated by the innate immune system and are effector cells of the adaptive immune system that affect the activity of other immune cells through secreted cytokines that mount an immune response against pathogens45. Our study showed instead that T cells were the predominant immune cell population in the luteal phase in our population of women with RIF. Interestingly, within the non-pregnant population, there is a further and significant increase in the T cell population after the LEI, possibly indicating further increased inflammation in the endometrium, attributable to both LEI and endometriosis. On the contrary, that was not observed in the pregnant group. This observation is congruent with Ganeva and colleagues’ findings where there were significantly lower CD3 + T cells in RIF women with a successful implantation than those who were unsuccessful46. However, comparison of the T cell population in the 2nd LEI sample between the pregnant and non-pregnant group in our study did not reveal any differences. This could be due to the large inter-patient variability, with a small sample size of 20 in the non-pregnant and 17 in the pregnant group. Nonetheless, our data along with others46 suggest that the LEI could have set off another mechanism to inhibit the T cell from further increase in women who respond positively.

Decidual NK cells contribute to pregnancy by increasing the blood flow through remodelling of maternal arterioles at the feto-maternal interface and helping the migration of the trophoblast. NK cells is also responsible for the secretion of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin-2, as well as cytokines and growth factors such as TNF-α, IL-10, GM-CSF, placental growth factor, IL-1β, TGF-β1, CSF-1, LIF, and IFN-γ47. Therefore, their distribution and activation at the time of fertilization and implantation plays a critical role in pregnancy outcome48. NK cells account for 20% of lymphocytes in the proliferative phase and increases to 40–50% in the luteal phase and a maximum of 70–80% during decidualization49,50. In contrast, NK cells represent approximately 26–29% of CD45 + leukocytes in our RIF population, as opposed to the nearly 70% of endometrial leucocytes in the late luteal phase or early pregnancy51,52. This corroborated with other studies on women with RIF53,54,55 and corresponds well with the postulation that women with subfertility may have lower uNK cells compared to healthy women. From our results, LEI does not alter the proportion of NK cells in women with RIF. NK cell subpopulations are identified by differential expression of a range of NK receptors56 whereby circulating NK cells are primarily CD56dim CD16bright whereas uNK cells are mostly CD56bright CD16[dim57. However, we did not distinguish this NK subpopulation which is a limitation of our study.

The next most abundant cell types are B cells, which are known to be found throughout the cycle, at low levels, corroborating with our findings of approximately 2% of the CD45 + cell population38,58. With their low levels, they have long been perceived as insignificant until more recently where they are shown to have distinct characteristics and may be actively involved in shaping the endometrial immune environment59. The quantity of B cells within the endometrium is altered in certain pathologies in presence of endometrial inflammation59. There are conflicting findings as to whether RIF patients have increased B-cell numbers59. In our study, within our definition of RIF patients, we showed an increase of 1.2% (50%) increase in the proportion of B cells within the entire cohort though non statistically significant. We observed a similar increase with B cells in both the non-pregnant and pregnant cohort (Fig. 4E), suggesting an inflammatory response with the LEI. A wide patient heterogeneity as well as a small sample size could have attributed to the statistical significance and more should be done to look at this.

Dendritic cells are APCs that process and present antigenic materials to T lymphocytes60,61 and bridge the innate and adaptive immune systems62,63. We noted a trend towards a reduction of both CD141 + DCs and CD1c + DCs though non statistically significant. Both CD141 + and CD1c + DCs have a common origin of myeloid precursors and produces pro-inflammatory IL-1B, 6, 8 and TNF64. They are also responsible for taking up, processing and presenting protein antigens to CD4 + and CD8 + T cells64. During pregnancy, the maternal-fetal interface undergoes dynamic changes to allow the fetus to grow and develop in the uterus, despite being recognized by the maternal immune cells. Our observation of the reduction in both DCs subtypes following an LEI may not have an impact difference as it is statistically non-significant but if that is due to the power of the study, this reduction could mean aiding in immune tolerance toward the semi-allogeneic fetus, contributing to the beneficial effects of LEI for women with RIF. Analysis of rare cells in the endometrium has its own set of challenges of weighing between the scientific benefits provided by a large sample volume versus the clinical and ethical difficulties of obtaining tissue65. A larger sample size, or the use of newer high resolution technologies like single cell analyses may be required to illuminate this field.

Overall, we did not find any significant changes of immune cell subtypes before and after LEI in subsequent luteal phase cycles in women with RIF. No significant differences were observed in DCs, macrophages, NK cells and B cells between the first and second Pipelle biopsy which is congruent with Ganeva at el where there were non-significant differences in median of percentages of T cells, NK cells, macrophages, monocytes and B cells46. Of particular interest, both their and our study showed a significant change in the T cells, although our participants of interest are different, theirs being women with RIF with and without a successful implantation while ours are women with RIF undergoing LEI with and without getting pregnant46. The immune landscape is different in women with RIF as compared to normal women. Endometrial immune dysregulation is also implicated in women with different pathologies including recurrent pregnancy loss, preterm labour and endometriosis66,67,68. In our study, twenty one (57%) and five women (14%) had unexplained fertility and endometriosis respectively. The peripheral and endometrial immune system are altered in women with endometriosis with macrophages, immature DCs and regulatory T cells behaving differently68,69,70 and that can confound our results, as observed with our T cells data.

The novelty of our study includes the approach to LEI involving the same patient over consecutive menstrual cycles where the use of uterine catheter acts as intervention while concurrently allows tissue collection. Patients also act as their own control which can reduce inter-patient variability that can confound results. In addition, we employed a validated assay (Fig. 2) that can interrogate the composition and content of the various immune cell subtypes with high specificity and sensitivity, circumventing the limitations of traditional methods analysis71,72. The approach of treating endometrial specimens as a cell suspension is a powerful approach as this technique has significant advantages over the traditional immuno-histochemical staining methods, including the ability to precisely interrogate multiple markers simultaneously from a single specimen and exclude false positive or negative signals from non-viable cells. That said, limitations of our study include a small sample size of fifty-three women with a high proportion of low-quality tissue (30%) and that our results are dependent on the Pipelle biopsies obtained which are beset by different sampling regions between patients as well as between the first and second LEI. Our attempts at identifying a mid-luteal phase rests upon the regularity of the menstrual cycle in addition to a rise in serum progesterone levels and hence does not confirm a mid-luteal timing definitively. We did not include histological confirmation of the secretory endometrium due to the necessity of using the entire sample for analysis. The design of our flow cytometry panel would exclude the CD3 + CD56 + NKT cells which is also another limitation. In addition, we did not perform subset analysis of the NK (uterine and non -uterine) and T cells. T cell subsets such as CD4, CD8 and T regulatory cells and their activation status which are implicated in patients with subfertility can further ascertain better understanding on the complex interactions between the innate and adaptive immune system during implantation and pregnancy.

In this small but well-defined RIF population where sequential paired samples were analysed by high resolution flow cytometry, the immune landscape had remained largely unchanged post LEI in women with RIF at the current resolution. An increase in sample size may help elucidate the difference but more importantly, further research in this area at a higher and more in depth resolution is required. These can be done by transcriptomics and applying RNA sequencing for gene expression analysis in a single cell manner. Elucidating the critical pathways surrounding the beneficial effects of LEI and uncovering the immune activation statuses of NK and T-cells in RIF patients will not only offer a deeper understanding of the critical events surrounding human implantation but opens the possibility of devising approaches to enhance fertility outcomes.

Materials and methods

Ethics approval

The current study was reviewed and approved by the SingHealth Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB 2013/215/D). Informed written consent was obtained for all participants before their participation in the study at KKIVF Centre, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria are women with RIF undergoing IVF with RIF defined as failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after a transfer of minimum four good-quality embryos in a minimum of two or more previous failed embryo transfers. Other inclusion factors include women < 40 years of age with primary subfertility with normal ovarian reserves, good response to ovarian stimulation and optimal luteal endometrial thickness > 7 mm at embryo transfer and a normal hormonal profile. Our exclusion criteria included women > 40 years old, BMI > 35 and women who do not meet our criteria for RIF or women who declined a repeat endometrial scratch in the following menstrual cycle. Serum progesterone was measured to check for ovulatory status. Serum beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (βhCG) was measured 17 days after IVF embryo transfer to determine if women became pregnant with a positive βhCG result > 25 mIU per milliliter. Clinical pregnancy rate was defined as the presence of intrauterine gestation sac on ultrasound scan 2 weeks after a positive βhCG result.

Sample collection and processing

To characterize the immunological landscape alterations in LEI, we performed sequential implantation-phase (mid-luteal) endometrial biopsies (first and second biopsies) in RIF patients prior to IVF. These women underwent two consecutive LEI with a Pipelle endometrial catheter to obtain endometrial tissue during the first and succeeding mid-luteal phase (Day 21–25) of their menstrual cycles (Fig. 1). The endometrial scratch procedure was performed by clinic doctors using a Pipelle, a plastic biopsy catheter approximately 3 mm in diameter (Pipelle de cornier, Laboratoire CCD, France).

Endometrial tissues obtained were minced into fragments and digested for 30 min at 37 °C with 1 mg/mL of collagenase type IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 0.2 mg/mL of DNase (Roche Applied Science, Germany) and 1 mg/mL of bovine serum albumin in PBS. The single cell suspension was passed through a mesh, washed in PBS, treated with Ammonium-Chloride-Potassium lysing buffer (0.01 M KHCO3 buffer, 0.16 M NH4Cl and 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) to remove red blood cells, washed and resuspended in PBS as previously described43.

Flow cytometry

Cells were blocked in human blocking buffer (5% human serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% rat serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% mouse serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 5% FBS, and 2 mM EDTA) for 15 min at 4 °C and incubated with antibody cocktails (Table 1) for 30 min at 4 °C. Cell suspensions were stained for viability with 1:3,000 DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Flow cytometric analyses were performed on an LSR II (Becton Dickinson) and data analysed with FlowJo software (TreeStar). Two antibody cocktails were used. Live cells (DAPI−) were first selected. Doublets were then removed and leukocytes (CD45+) identified. With the first antibody cocktail, tissue CD14+ macrophages, pDCs, CD141+ DCs, CD1c+ DCs were identified (Fig. 2Ai). Antigen presenting cells were identified as HLA-DR+ and lineage (CD3, CD19, CD20)−. CD14+ macrophages which also express the macrophage markers CD163 and CD64 were enumerated. From the CD14-CD16- fraction, pDCs were identified by CD123+ and CD11c−. From the CD123−CD11c− population, while CD141+CD1c− and CD1c+CD141− were enumerated. With the second antibody cocktail, CD3+ T cells, CD19+CD20+ B cells and CD56+ NK cells were identified and enumerated (Fig. 2Aii).

Statistical analysis

The data is presented as mean ± standard deviation. Normality of continuous variables was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparison between first and second LEI was performed using non-parametric (Mann-Whitney for unpaired or Wilcoxon signed-ranked test for paired data) tests when Gaussian distribution is not observed or Student’s t-test when Gaussian distribution is followed. Statistical analysis was performed with Graphpad Prism 10. A two-sided p-value at the 5% level was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings are available within the article. Please contact the corresponding author for more information.

References

Luke, B. et al. Cumulative birth rates with linked assisted reproductive technology cycles. N Engl. J. Med. 366, 2483–2491. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1110238 (2012).

Karimzadeh, M. A., Ayazi Rozbahani, M. & Tabibnejad, N. Endometrial local injury improves the pregnancy rate among recurrent implantation failure patients undergoing in vitro fertilisation/intra cytoplasmic sperm injection: a randomised clinical trial. Aust N Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 49, 677–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01076.x (2009).

Revel, A. Defective endometrial receptivity. Fertil. Steril. 97, 1028–1032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.03.039 (2012).

Segev, Y., Carp, H., Auslender, R. & Dirnfeld, M. Is there a place for adjuvant therapy in IVF? Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 65, 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181dbc53f (2010).

Dekel, N., Gnainsky, Y., Granot, I. & Mor, G. Inflammation and implantation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 63, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00792.x (2010).

Tan, B. K., Vandekerckhove, P., Kennedy, R. & Keay, S. D. Investigation and current management of recurrent IVF treatment failure in the UK. BJOG 112, 773–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00523.x (2005).

Baum, M. et al. Does local injury to the endometrium before IVF cycle really affect treatment outcome? Results of a randomized placebo controlled trial. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 28, 933–936. https://doi.org/10.3109/09513590.2011.650750 (2012).

Coughlan, C. et al. Recurrent implantation failure: definition and management. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 28, 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.08.011 (2014).

Polanski, L. T. et al. What exactly do we mean by ‘recurrent implantation failure’? A systematic review and opinion. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 28, 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.12.006 (2014).

Barash, A. et al. Local injury to the endometrium doubles the incidence of successful pregnancies in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 79, 1317–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00345-5 (2003).

Zhou, L., Li, R., Wang, R., Huang, H. X. & Zhong, K. Local injury to the endometrium in controlled ovarian hyperstimulation cycles improves implantation rates. Fertil. Steril. 89, 1166–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.064 (2008).

Lensen, S., Sadler, L. & Farquhar, C. Endometrial scratching for subfertility: everyone’s doing it. Hum. Reprod. 31, 1241–1244. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dew053 (2016).

Potdar, N., Gelbaya, T. & Nardo, L. G. Endometrial injury to overcome recurrent embryo implantation failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 25, 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.08.005 (2012).

Nastri, C. O. et al. Endometrial injury in women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. CD009517 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009517.pub3 (2015).

Yeung, T. W. et al. The effect of endometrial injury on ongoing pregnancy rate in unselected subfertile women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a randomized controlled trial. Hum. Reprod. 29, 2474–2481. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu213 (2014).

El-Toukhy, T., Sunkara, S. & Khalaf, Y. Local endometrial injury and IVF outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Biomed. Online. 25, 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbmo.2012.06.012 (2012).

Sar-Shalom Nahshon, C., Sagi-Dain, L., Wiener-Megnazi, Z. & Dirnfeld, M. The impact of intentional endometrial injury on reproductive outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 25, 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmy034 (2019).

Vitagliano, A. et al. Endometrial scratch injury for women with one or more previous failed embryo transfers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Fertil. Steril. 110 (e682), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.040 (2018).

van Hoogenhuijze, N. E., Kasius, J. C., Broekmans, F. J. M., Bosteels, J. & Torrance, H. L. Endometrial scratching prior to IVF; does it help and for whom? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2019 (hoy025). https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoy025 (2019).

Lensen, S. et al. A randomized trial of endometrial scratching before in vitro fertilization. N Engl. J. Med. 380, 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1808737 (2019).

van Hoogenhuijze, N. E. et al. Endometrial scratching in women with one failed IVF/ICSI cycle-outcomes of a randomised controlled trial (SCRaTCH). Hum. Reprod. 36, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa268 (2021).

Simon, C. & Bellver, J. Scratching beneath ‘The scratching case’: systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the back door for evidence-based medicine. Hum. Reprod. 29, 1618–1621. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deu126 (2014).

Fan, Y., Lee, R. W. K., Ng, X. W., Gargett, C. E. & Chan, J. K. Y. Subtle changes in perivascular endometrial mesenchymal stem cells after local endometrial injury in recurrent implantation failure. Sci. Rep. 13, 225. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-27388-8 (2023).

Cakmak, H. & Taylor, H. S. Implantation failure: molecular mechanisms and clinical treatment. Hum. Reprod. Update. 17, 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmq037 (2011).

Gnainsky, Y. et al. Biopsy-induced inflammatory conditions improve endometrial receptivity: the mechanism of action. Reproduction 149, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-14-0395 (2015).

Granot, I., Gnainsky, Y. & Dekel, N. Endometrial inflammation and effect on implantation improvement and pregnancy outcome. Reproduction 144, 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1530/REP-12-0217 (2012).

Arck, P. C. & Hecher, K. Fetomaternal immune cross-talk and its consequences for maternal and offspring’s health. Nat. Med. 19, 548–556. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3160 (2013).

Saito, S. et al. Distribution of Th1, Th2, and Th0 and the Th1/Th2 cell ratios in human peripheral and endometrial T cells. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 42, 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0897.1999.tb00097.x (1999).

Brosens, I., Pijnenborg, R., Vercruysse, L. & Romero, R. The great obstetrical syndromes are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 204, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.009 (2011).

Gnainsky, Y., Dekel, N. & Granot, I. Implantation: mutual activity of sex steroid hormones and the immune system guarantee the maternal-embryo interaction. Semin Reprod. Med. 32, 337–345. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1376353 (2014).

Wegmann, T. G., Lin, H., Guilbert, L. & Mosmann, T. R. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol. Today. 14, 353–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D (1993).

Haniffa, M. et al. Human tissues contain CD141hi cross-presenting dendritic cells with functional homology to mouse CD103 + nonlymphoid dendritic cells. Immunity 37, 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.012 (2012).

Vitagliano, A. et al. Endometrial scratching can be offered outside clinical research setting: let Us show you why. Hum. Reprod. 36, 1447–1449. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deab060 (2021).

Dickinson, R. E. et al. The evolution of cellular deficiency in GATA2 mutation. Blood 123, 863–874. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-07-517151 (2014).

van Hoogenhuijze, N. E. et al. Endometrial scratching in women undergoing IVF/ICSI: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 29, 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmad014 (2023).

Kammerer, U., von Wolff, M. & Markert, U. R. Immunology of human endometrium. Immunobiology 209, 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2004.04.009 (2004).

Flynn, L. et al. Menstrual cycle dependent fluctuations in NK and T-lymphocyte subsets from non-pregnant human endometrium. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 43 (4), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.8755-8920.2000.430405.x (2000).

Salamonsen, L. A. & Lathbury, L. J. Endometrial leukocytes and menstruation. Hum. Reprod. Update. 6, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/6.1.16 (2000).

Schlitzer, A., McGovern, N. & Ginhoux, F. Dendritic cells and monocyte-derived cells: two complementary and integrated functional systems. Semin Cell. Dev. Biol. 41, 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.03.011 (2015).

Brighton, P. J. et al. Clearance of senescent decidual cells by uterine natural killer cells in cycling human endometrium. Elife 6 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.31274 (2017).

Marron, K., Walsh, D. & Harrity, C. Detailed endometrial immune assessment of both normal and adverse reproductive outcome populations. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 36, 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-018-1300-8 (2019).

Fan, X. et al. Immune profiling and RNA-seq uncover the cause of partial unexplained recurrent implantation failure. Int. Immunopharmacol. 121, 110513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110513 (2023).

Gnainsky, Y. et al. Local injury of the endometrium induces an inflammatory response that promotes successful implantation. Fertil. Steril. 94, 2030–2036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.02.022 (2010).

Givan, A. L. et al. Flow cytometric analysis of leukocytes in the human female reproductive tract: comparison of fallopian tube, uterus, cervix, and vagina. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 38, 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00311.x (1997).

Raphael, I., Nalawade, S., Eagar, T. N. & Forsthuber, T. G. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine 74, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2014.09.011 (2015).

Ganeva, R. et al. Endometrial immune cell ratios and implantation success in patients with recurrent implantation failure. J. Reprod. Immunol. 156, 103816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jri.2023.103816 (2023).

Lee, J. Y., Lee, M. & Lee, S. K. Role of endometrial immune cells in implantation. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 38, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.5653/cerm.2011.38.3.119 (2011).

Carlino, C. et al. Recruitment of Circulating NK cells through decidual tissues: a possible mechanism controlling NK cell accumulation in the uterus during early pregnancy. Blood 111, 3108–3115. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-08-105965 (2008).

Moffett-King, A. Natural killer cells and pregnancy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 656–663. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri886 (2002).

Dosiou, C. & Giudice, L. C. Natural killer cells in pregnancy and recurrent pregnancy loss: endocrine and Immunologic perspectives. Endocr. Rev. 26, 44–62. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2003-0021 (2005).

Okada, H., Tsuzuki, T. & Murata, H. Decidualization of the human endometrium. Reprod. Med. Biol. 17, 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmb2.12088 (2018).

Lee, S. K., Kim, C. J., Kim, D. J. & Kang, J. H. Immune cells in the female reproductive tract. Immune Netw. 15, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.4110/in.2015.15.1.16 (2015).

Kofod, L., Lindhard, A. & Hviid, T. V. F. Implications of uterine NK cells and regulatory T cells in the endometrium of infertile women. Hum. Immunol. 79, 693–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2018.07.003 (2018).

Giuliani, E., Parkin, K. L., Lessey, B. A., Young, S. L. & Fazleabas, A. T. Characterization of uterine NK cells in women with infertility or recurrent pregnancy loss and associated endometriosis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 72, 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/aji.12259 (2014).

Matteo, M. G. et al. Normal percentage of CD56bright natural killer cells in young patients with a history of repeated unexplained implantation failure after in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil. Steril. 88, 990–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.01.028 (2007).

Koopman, L. A. et al. Human decidual natural killer cells are a unique NK cell subset with Immunomodulatory potential. J. Exp. Med. 198, 1201–1212. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20030305 (2003).

Caligiuri, M. A. Human natural killer cells. Blood 112, 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438 (2008).

Shen, M. et al. B cell subset analysis and gene expression characterization in Mid-Luteal endometrium. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 709280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.709280 (2021).

Shen, M. et al. The role of endometrial B cells in normal endometrium and benign female reproductive pathologies: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Open. 2022, hoab043. https://doi.org/10.1093/hropen/hoab043 (2022).

Kambayashi, T. & Laufer, T. M. Atypical MHC class II-expressing antigen-presenting cells: can anything replace a dendritic cell? Nat. Rev. Immunol. 14, 719–730. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3754 (2014).

Haniffa, M., Collin, M. & Ginhoux, F. Ontogeny and functional specialization of dendritic cells in human and mouse. Adv. Immunol. 120, 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00001-6 (2013).

Villadangos, J. A. & Schnorrer, P. Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri2103 (2007).

Boltjes, A. & van Wijk, F. Human dendritic cell functional specialization in steady-state and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 5, 131. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2014.00131 (2014).

Jongbloed, S. L. et al. Human CD141+ (BDCA-3) + dendritic cells (DCs) represent a unique myeloid DC subset that cross-presents necrotic cell antigens. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1247–1260. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20092140 (2010).

Rodriguez-Garcia, M., Fortier, J. M., Barr, F. D. & Wira, C. R. Isolation of dendritic cells from the human female reproductive tract for phenotypical and functional studies. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/57100 (2018).

Ticconi, C., Pietropolli, A., Di Simone, N., Piccione, E. & Fazleabas, A. Endometrial immune dysfunction in recurrent pregnancy loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20215332 (2019).

Wilczyński, J. R. Immunological analogy between allograft rejection, recurrent abortion and pre-eclampsia - the same basic mechanism? Hum. Immunol. 67, 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2006.04.007 (2006).

Vallve-Juanico, J., Houshdaran, S. & Giudice, L. C. The endometrial immune environment of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update. 25, 564–591. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmz018 (2019).

Patel, B. G. et al. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: interaction between endocrine and inflammatory pathways. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 50, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2018.01.006 (2018).

Agic, A. et al. Is endometriosis associated with systemic subclinical inflammation? Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 62, 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1159/000093121 (2006).

Hoeffel, G. et al. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 209, 1167–1181. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20120340 (2012).

McGovern, N. et al. Human dermal CD14(+) cells are a transient population of monocyte-derived macrophages. Immunity 41, 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.006 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr Sadhana Nadarajah, Dr Tan Heng Hao, Miss Ng Xiang Wen from KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital for clinical administrative support, Mr Gurmit Singh from Singapore Immunology Network (SIgN) for tissue sample processing and flow cytometry analysis.

Funding

This study was supported by the KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital Health Endowment Fund (KKHHEF/2013/07), Academic Medicine Start up Grant (AM/SU101/2024), Improving Fertility Outcomes in Women Programme Fund sponsored by Melilea International Group of Companies, and National Medical Research council (NMRC) seed fund (0004/2017). JKYC is supported by National Medical Research Council (CIRG/1484/2018, NMRC CSA (SI)/008/2016, CIRG21jun-0045 and STaR22jul-0004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FG, YHL and JKYC study conceptualization. AM and NM designed and performed the flow experiments. RWKL, YF, YHL analysed the data and drafted the paper. RWKL, TYT, JKYC obtained funding, consented patients and collected data. All authors read, reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Y., Lee, R.W.K., Mishra, A. et al. The immune milieu after local endometrial injury in women with recurrent implantation failure. Sci Rep 16, 4135 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34198-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34198-7