Abstract

Loess, characterized by its high porosity, low strength, and sensitivity to weather conditions, presents significant challenges for sustainable infrastructure development. Conventional stabilization methods using lime and cement contribute substantially to greenhouse gas emissions and embodied energy. This study proposes a novel and eco-friendly approach for loess soil stabilization by incorporating nanosilica (NS) and ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), an industrial byproduct, to enhance mechanical performance while minimizing environmental impact. Special attention was given to sustainability aspects, including waste valorization, carbon emissions reduction, embodied energy, and practical feasibility. GGBS was combined with NS to improve the mechanical performance of the soil. Different NS contents (0.4%, 0.7%, 1%, and 1.3%) were evaluated, with 1% NS providing optimal pore filling and uniform dispersion. Subsequently, GGBS was added at varying concentrations (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) to the NS-treated loess. The samples cured for 7 and 28 days were subjected to freeze–thaw cycle testing. Experimental characterization included unconfined compressive strength (UCS), ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV), collapse potential (CP), and microstructural analyses (SEM, XRD, FTIR, and BET). The optimal mix increased UCS by up to 24 times, with only a reduction of 9% after 10 freeze–thaw cycles. Microstructural analyses confirmed the formation of C–S–H and C–A–S–H gels, which led to soil densification. A quantitative sustainability assessment showed the reduction of carbon emissions by over 60% compared to traditional stabilization methods, along with decreased costs, emphasizing significant environmental and economic benefits. This method not only improves mechanical performance but also values industrial waste, thereby providing a scalable, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable solution for loess stabilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Various soil types, particularly weak soils, impose significant challenges in civil engineering projects, potentially compromising structural stability and safety1,2. Weak soils, such as clayey and loess deposits, exhibit moisture sensitivity and collapsibility, rendering them vulnerable to heavy loads and environmental variations3. These properties may trigger uneven settlement, foundation failure, or even structural collapse4,5. Consequently, geotechnical engineers must thoroughly understand the behavior of these soils and implement appropriate stabilization techniques to enhance bearing capacity and mitigate associated risks during infrastructure design and construction6,7. Loess soils, characterized by their porous microstructure and pronounced hydro-sensitivity, demand particular attention in engineering projects owing to their heightened susceptibility to loading and climatic fluctuations8,9. Another major challenge is their vulnerability to freeze–thaw cycles (FTCs), which greatly affect both their mechanical properties and microstructural integrity10. The existence of loess soils throughout the world and their inherent geotechnical deficiencies have highlighted the need to improve their mechanical performance and durability through stabilization11.

Applying nanoparticles in stabilizing weak soils has emerged as an innovative approach in engineering12,13. Nanoparticles can enhance the mechanical and physical properties of soils as a result of their unique physical and chemical characteristics, such as a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and the capacity to form effective chemical bonds with soil particles14. Cheraghali Khani et al.15 employed soil stabilization with nano illite as a new method and reported that adding 3% nano illite increases the soil’s compressive strength by more than 2.2 times and the elastic modulus by more than 1.5 times. The micro and nano structures of the soil were investigated using XRF, SEM, and XRD, confirming the performance of nano illite as an effective additive in improving soil properties. In studies on loess modification, using nanosilica (NS) has attracted considerable attention16. Iranpour and Haddad17 investigated the effect of NS on the collapse potential (CP) of loess soils. They showed that NS reduces the amount of soil collapse, although not into the safe (slight) range. Haeri and Valishzadeh18 studied the stabilization of loess using various nanomaterials, such as NS. They found that the CP grade of the stabilized loess was improved from relatively severe for unstabilized soil to moderate for stabilized soils. Moreover, the compressive strength of loess soil stabilized with NS under optimal conditions was still low (less than 600 kPa). Ai et al.19 examined only one FTC on loess soil stabilized with 2.5% NS and clearly demonstrated the destructive effect of the FTCs on the loess soil. They also revealed that NS could only limit this progressive deterioration to a certain extent. Given the identified gaps in previous studies on stabilizing loess soils with NS, such as non-desirable mechanical strength and insufficient durability against FTCs, another additive seems to be required alongside NS to further improve the properties of loess soils.

Calcium-based stabilizers, including traditional stabilizers, have been widely adopted in geotechnical engineering to enhance the mechanical properties of weak soils20,21. Traditional stabilizers, such as lime, fly ash, and cement, improve soil strength and stability through chemical reactions with loess soil particles, but they also have significant problems22,23. Researchers have also found that using traditional stabilizers in loess is associated with ground warming and can change the acid–base balance of the environment24,25. Given the drawbacks of traditional stabilizers, such as cement and lime, including high costs, environmental impacts, and durability concerns, there is a growing research focus on developing environmentally friendly alternatives to effectively address these challenges. Reusing industrial waste for the stabilization of loess soils is a new solution that has been considered26,27.

Ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), a byproduct of steel manufacturing, is produced through rapid quenching of molten slag with water or steam. GGBS has attracted attention in recent years for stabilizing loess soils28,29. Guo et al.30 examined the performance of lime and a lime-GGBS combination in stabilizing loess soil. The combination of lime and GGBS increased the compressive strength of stabilized loess soil several times more than lime alone, but its performance under harsh environmental conditions, such as repeated FTCs, required further investigation. Besides, Sun et al.29 investigated a ternary blend containing waste tire textile fibers, red mud, and GGBS for stabilizing lead-contaminated loess soil. They proposed this stabilized loess soil as a landfill embankment or solid waste bedding material. Wu et al.31 also attempted to reduce the destructive effects of repeated wet-dry cycles on loess soil by using a combination of steel slag and GGBS.

Previous studies have independently examined the stabilization of loess with NS and GGBS, demonstrating enhancement in its mechanical properties. However, their effectiveness in reducing the harmful effects of FTC has often been limited. Furthermore, while utilizing industrial by-products is encouraged, a comprehensive assessment of the environmental and economic benefits of such stabilizers in the context of a circular economy remains a potential area of investigation. To address these research gaps, the present study investigated the synergistic effects of a combined NS-GGBS stabilization system on the mechanical performance, durability, and microstructural evolution of loess soil subjected to repeated FTC. Environmental criteria, such as carbon emissions and embodied energy, and cost-effectiveness and practical implications, were investigated. The experimental procedures included 7 and 28-day curing periods, followed by sequential FTCs (0, 1, 4, and 10 cycles). Mechanical and durability parameters were measured using unconfined compressive strength (UCS), collapse potential (CP), and ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) tests. Microstructural analyses, including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), were performed to elucidate the hydration mechanisms and formation of strength-enhancing phases. In addition, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis was performed to quantify changes in porosity and specific surface area (SSA).

Materials and methods

Materials

The loess specimens were extracted from natural trenches in the Neka region, located in northern Iran. Table 1 presents the physical characteristics of loess. Table 2 shows the XRF test results related to the chemical composition of the materials, including loess, GGBS, and NS. Loess mainly contains high percentages of silica (53.2%), alumina (12.4%), and calcium oxide (15.4%), which constitute its main mineral composition. GGBS has a high content of calcium (44.16%) and silica (39.04%), which characterize its strong pozzolanic properties. NS is almost entirely composed of silica (99.5%) and can be used as an active and reactive material to improve soil properties.

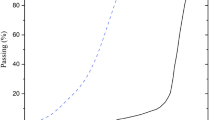

Figure 1 displays the grain size distribution curve of loess and GGBS, determined through a combination of sieve and hydrometer testing based on ASTM D42232. Due to its smaller particle size, GGBS can act as an effective filler within the soil matrix by occupying the voids between loess particles, thereby stabilizing the metastable structure of loess through improved particle contacts. It also has a higher SSA than loess, which allows for uniform distribution of water in the soil matrix. Besides, it improves soil compaction during stabilization by placement between loess particles.

GGBS is a byproduct of steel manufacturing, produced through the rapid quenching of molten slag with water or steam. It was sourced from an industrial complex in Iran. Figure 1 shows the particle size distribution curve based on ASTM D42232. Table 3 also summarizes the technical specifications of the NS material.

Methods

Sample preparation

During sample preparation, the loess soil was first passed through a No. 40 sieve (standard mesh) and then oven-dried. Each soil sample was divided into three equal parts, and specified amounts of the additives (NS and GGBS) were introduced into each portion. The mixtures were manually homogenized for 10 min33. Subsequently, all three portions were combined in a cylindrical mold to achieve a thoroughly uniform blend (Fig. 2). The optimum water content, determined from compaction tests, was added to each sample in three increments, followed by an additional 10 min of mixing to ensure homogeneity1. The moist mixtures were then poured into steel cylindrical molds (38 × 76 mm) in three layers. A hydraulic jack was employed to apply a static compaction force, ensuring that MDD was attained. Studies on soil stabilization with CaO2-rich materials typically select curing periods of 7 and 28 days to represent early and medium-term mechanical behavior development; the same curing periods were chosen in this study34.

A 1-day curing time was used for loess and NS mixtures, since prior studies reported significant strength gains from NS within the first 24 h due to pore filling, matrix homogenization, and hydration reactions35,36. This rapid strength development is valuable for projects requiring prompt initial strength, such as roadbeds in cold climates or staged pavement construction37. Control samples were also tested after a day to ensure uniform moisture. Besides, strength changes in untreated soil after one day are not expected to be significant according to previous studies15,38. All the tests were conducted in triplicate using mean values. Table 4 summarizes the mixed compositions, curing periods, FTC conditions, and testing details.

Mechanical and microstructure tests

UCS tests were conducted on specimens at a strain rate of 1.2 mm/min following ASTM39. The optimal percentages of NS and GGBS were determined based on the highest UCS peak values. Three specimen categories were prepared for FTC assessment: (1) untreated loess, (2) NS-stabilized loess at varying concentrations, and (3) composite NS-GGBS-stabilized loess with optimized NS content. All the cured specimens underwent closed-system FTC testing while being vacuum-sealed in plastic bags to preserve constant moisture content. Each complete FTC consisted of 12 h at − 23 °C followed by 12 h at + 20 °C.. This procedure was repeated to achieve 0, 1, 4, and 10 FTCs. UCS testing was performed initially and after completing 1, 4, and 10 FTCs40. The first and tenth cycles were selected for analysis because the first cycle showed the greatest damage, and the tenth cycle represented a stable condition with minimal changes in soil resistance, enabling meaningful comparison with prior studies25,34.

The CP test was conducted according to ASTM D533341 to evaluate the CP of the samples. The experimental procedure involved placing the soil specimen in a consolidometer and applying controlled vertical stress. The sample was saturated with distilled water to induce the collapse behavior42. UPV testing, following ASTM C 59743, was used to measure the constrained modulus (D) of untreated and treated loess with a digital device. Sample surfaces were prepared with acoustic grease to enhance wave transmission. P-wave velocities were recorded at initial conditions and after the 1st, 4th, and 10th FTCs, with stiffness changes evaluated via Mandel et al.'s model44. Additionally, BET surface area analysis quantified the SSA of solid samples based on gas adsorption45, providing insight into soil and stabilizer microstructure4. FTIR, XRD, and SEM analyses were conducted to study the microstructural behavior and mineralogical changes in the samples. XRD analyses were conducted using a PANalytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer equipped with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), operating at 40 kV and 30 mA. The scanning range extended from 5° to 70° (2θ), with a step size of 0.02°/s, providing adequate resolution for distinguishing both crystalline and amorphous phases. Phase identification and semi-quantitative analysis were performed using HighScore Plus software (PANalytical, version 4.9) in combination with the ICDD PDF-4 + database. HighScore Plus facilitates precise peak deconvolution and background correction, enabling the identification of weak and broad diffraction peaks commonly associated with amorphous or poorly crystalline hydration products, such as C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels. In this study, a broad hump detected between 27° and 34° (2θ) was analyzed using Gaussian fitting within HighScore Plus, revealing a diffuse pattern indicative of low-crystalline C-S–H and C-A-S–H gel formation.

Sustainability and applicability investigations

Embodied energy refers to the total amount of energy required to produce a material or product, including the extraction of raw materials, processing, manufacturing, transportation, and delivery to the site of use46,47. Embodied energy is a metric used to compare the global warming potential of different construction materials. In this study, using GGBS and NS, the total embodied energy (expressed in megajoules (MJ)) was considered for stabilizing 1 ton of soil and compared with that needed for stabilizing one ton of soil using cement and lime.

Carbon emissions denote the release of carbon-containing compounds, primarily carbon dioxide (CO2), into the atmosphere48. These emissions predominantly result from the combustion of fossil fuels and significantly increase the greenhouse effect, thereby driving global warming. In this study, the carbon emissions of GGBS and NS, along with two conventional stabilizers (lime and cement), were calculated and compared (in kilograms) for stabilizing one ton of soil. Additionally, a cost assessment was conducted by calculating the expense of each material necessary to stabilize one ton of soil, based on current global market prices expressed in US dollars. Hence, an economic basis was provided for comparison alongside environmental metrics. Finally, based on the results of the stabilized silty soil, its performance in various projects was analyzed considering the specific criteria of each project. Real projects were presented using the proposed method to improve performance in terms of implementation, cost, and sustainability, taking into account environmental aspects.

Results and discussion

Compaction tests

Figure 3a presents the effect of different NS percentages on the MDD and OMC of unstabilized loess soil. Adding NS at 0.4%, 0.7%, 1%, and 1.3% reduced the dry unit weight. Due to the significantly lower unit weight of NS, its interaction with the soil reduced the dry unit weight of the stabilized soil. Given its exceptionally high SSA resulting from its nano-scale properties, NS absorbed moisture. Consequently, the OMC of the soil increased with the addition of NS. Similar findings were reported in prior research utilizing NS for stabilizing various soil types49,50. Figure 3b demonstrates the influence of different GGBS percentages on the MDD and OMC of soil stabilized with 1% NS. Incorporating GGBS at 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% of the dry soil weight into the 1% NS-stabilized loess increased the dry unit weight. Furthermore, the OMC decreased upon raising the GGBS content. The OMC and MDD values for the sample containing 1% NS and 15% GGBS were measured at 14.1% and 1.68 g/cm3, respectively.

Stress–strain behavior and unconfined compression tests

Figure 4a illustrates the stress–strain behavior of loess containing different NS contents. The strength increased steadily with NS addition and reached its peak at 1% NS, confirming this percentage as the optimum dosage. This improvement is attributed to enhanced interparticle bonding through cementitious gel formation and void filling, according to the literature49. Beyond 1% silica nanoparticles, the curve showed a significant drop in peak stress and a decrease in strain at the fracture point. According to previous studies, this is attributed to the aggregation of nanoparticles and the decrease in matrix uniformity51,52.

Figure 4b,c present the stress–strain behavior of loess stabilized with 1%NS and different GGBS contents. The results demonstrated that increasing the GGBS content up to 15% enhanced the peak values of UCS, while higher GGBS contents beyond the 15% threshold resulted in strength reduction. The mechanical strength improvement at 1% NS + ≤ 15% GGBS content stemmed from the improved formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S–H) and calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (C-A-S–H) gels through hydration reactions between loess and GGBS53. However, exceeding a 15% GGBS content diminished the UCS, which was attributed to excessive gel formation and sample brittleness, outweighing the beneficial effects of gel formation54. Based on the experimental results, the 15% GGBS content revealed optimal UCS performance and was consequently selected as the ideal mix proportion.

The 1% NS treatment yielded nearly threefold strength enhancement compared to the unstabilized samples. However, increasing the NS content to 1.3% resulted in compressive strength values less than those of the untreated soil, primarily due to nano particle aggregation and soil clumping phenomena, consistent with previous research findings55,56. This strength reduction mechanism occurs when excessive NS particles form clusters rather than dispersing uniformly. Thus, weak points are created in the soil matrix instead of enhancing particle bonding.

Figure 5 illustrates the UCS of soil samples stabilized with 1% NS and different GGBS percentages. According to the experimental data, the specimens containing 15% GGBS achieved a compressive strength of 2368.1 kPa after 28 days of curing, representing a significant improvement over the control sample (96.6 kPa). During the 7-day curing period, incorporating 15% GGBS produced a 12-fold enhancement in compressive strength relative to the untreated soil, which further developed a 24-fold increase after 28 days of curing.

One of the reasons for this increase is NS, which increases hydration, especially at early ages57. NS also causes calcium oxide and silicate in the soil mixture to act more actively in soil stabilization58. Another reason for the significant increase in strength is adding optimized GGBS with a high silicate (39%) and calcium oxide content (44%) to the optimized mixture of NS with loess. Moreover, previous studies have reported such a trend for increasing strength. In the study by Jamal Ahmed et al., where GGBS alone was used to stabilize fine-grained soils, the UCS value of stabilized soil increased more than 8 times compared to the unstabilized soil. In the study by Godari and Salimi59, it was shown that adding 15% GGBS to a soil increased the pH value to nearly 11.5, indicating the onset of long-term reactions (i.e., pozzolanic activity); after 28 days of curing, the UCS of the sample stabilized with 15% GGBS reached nearly 3 MPa. Vastrat et al.60, who used NS and GGBS in the stabilization of black cotton soil, reported that GGBS alone increased the UCS by nearly three times and, together with NS, by up to 6 times compared to the unstabilized soil. In another study utilizing slag and NS to stabilize soft soil, a 54-fold increase in UCS was reported for the stabilized soil after 28 days of curing compared to the unstabilized soil61.

Figure 6 compares the UCS variations of the stabilized samples exposed to FTCs. Ice crystal formation and subsequent melting during FTCS created porous regions and microcracks in the soil matrix62. Increasing the number of cycles, these microcracks expanded further, causing a continuous decline in UCS over time34. Given the response of loess soil to FTCs exhibiting a 64% strength loss after 10 cycles, it is essential to stabilize and reinforce this specific soil type. For the samples stabilized with 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% GGBS, UCS reduction rates after 10 FTCs were 29%, 14%, 9%, and 26%, respectively. The sample containing 15% GGBS successfully reduced the UCS decline from 64% (observed in untreated loess) to below 10%. Li et al.63 used lignosulfonate to stabilize loess from the Northern China Loess Plateau and found that the strength reduction after 20 FTCs was limited to 34%.

Ultrasonic tests

Figure 7 illustrates the evolution of D of loess soils subjected to different treatment conditions over 28 days of curing and subsequent FTCs. The stabilized composite with 1% NS and 15% GGBS demonstrated a remarkable 11-fold increase in D values compared to untreated soil. This substantial enhancement can be primarily attributed to microstructural densification driven by pozzolanic reactions. GGBS and NS reacted with calcium, silicon, and alumina compounds in the soil to produce C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels. These gels filled pores and bound soil particles more effectively, increasing the stiffness and load-bearing capacity. Moreover, microstructural refinement significantly improved the soil’s resistance to environmental stressors, as evidenced by its performance after FTCs.

After 10 FTCs, the NS-GGBS stabilized soil exhibited a significantly smaller reduction in UCS (9%) than the untreated samples (33%), highlighting its enhanced resistance to FTCs. The microstructural densification and formation of durable gel phases diminished pore connectivity and microcrack propagation caused by FTCs, enhancing the FTC resistance. In contrast, Boz et al.40 reported higher vulnerability in lime-treated soils, with a 50% reduction at just 3% lime content, suggesting that NS and GGBS provided more effective microstructural stabilization against environmental degradation. Overall, these findings demonstrate that NS and GGBS markedly improve the initial mechanical properties and significantly enhance durability under FTC conditions, which makes them suitable for cold-region geotechnical applications.

Collapse potential (CP) test

The results of evaluating the collapsibility degree for loess, based on ASTM D533341, indicate that with a CP value of 14.34, this soil was classified as severe (Fig. 8). Applying a stabilizing mixture consisting of 1% NS and 15% GGBS significantly improved the geotechnical behavior of the soil, reducing the CP to 9.03 after 7 days of curing. Extending the curing period to 28 days further decreased this index to 1.65, placing the stabilized sample in the slight (relatively minor) category according to the standard classification. This behavioral improvement represented an 88% reduction in the CP due to stabilization. The present findings qualitatively align with the results of Safdar et al.64, where using 8% bagasse ash (BA) for stabilizing loess with an initial CP of 11.15 reduced it to 0.95.

. Microstructural analysis

BET tests

The results of the samples’ BET analysis are shown in Table 5. The data reveal that the monolayer adsorbed gas volume (Vₘ) decreased significantly from 3.5252 cm3/g in the untreated sample to 1.3072 cm3/g in the dual-treated specimen. This substantial reduction indicates that the combined GGBS and NS treatment effectively diminished pore volume and surface accessibility within the soil matrix. The notable decrease in Vₘ in the GGBS-NS sample suggests that nanoparticle infiltration and pozzolanic reactions fostered pore filling and pore occlusion, thereby creating a denser, less permeable structure. The additional pozzolanic activity of GGBS promoted the formation of C-S–H gels and other reaction products that further contributed to pore refinement and microstructural densification. This is consistent with improvements observed in macroscopic properties, such as increased UCS and decreased CP.

Besides pore volume, the SSA parameters (BET (aₛ, BET) and Langmuir (aₛ, Langmuir)) also exhibited marked reductions following combined treatment, with values around 5.7–6.2 m2/g compared to approximately 13–15 m2/g in the NS-only and untreated samples. This significant decrease reflects a substantial reduction in accessible surface area due to nanoparticle infiltration and the precipitation of pozzolanic reaction products within the pore network. The effective pore size refinement and wall coverage facilitated by the synergistic interaction of GGBS and NS led to decreased porosity and enhanced soil matrix integrity. These microstructural improvements corroborate the macroscopic mechanical enhancements observed in the stabilized samples, notably lower CP. The high strength can be attributed to the synergistic effect of NS and GGBS. The infiltration of nanoparticles, coupled with accelerated pozzolanic reactions, particularly the formation of C-S–H gel, leads to pore filling and pore occlusion. This process creates a denser and less permeable soil matrix, significantly enhancing mechanical strength and stability. The combined GGBS-NS treatment outperformed the singular NS application in improving soil stability and durability. Overall, the microstructural modifications captured in Table 5 underscore the crucial role of pore structure and surface area reduction in soil stabilization, emphasizing the effectiveness of the dual-additive approach to achieve improved structural and mechanical performance.

XRD

Figure 9 presents the XRD patterns of four distinct loess samples, i.e., untreated loess, loess stabilized with 15% GGBS, loess stabilized with 1% NS, and loess stabilized with 1% NS + 15% GGBS, after 28 days of curing.

The diffraction pattern (Fig. 9) of untreated loess exhibits prominent peaks corresponding to quartz (Q), calcite (C), feldspar (F), and clay minerals such as kaolinite (K), confirming their presence as primary constituents. The relatively low peak intensities reflect a well-defined crystalline structure that fundamentally governs the soil’s physicochemical characteristics. As shown in Fig. 9, the XRD pattern of loess mixed with GGBS shows the dominant crystalline peaks of quartz (Q), calcite (C), and feldspar (F) inherited from the parent loess, with minor modifications compared to the untreated soil. A slight increase in baseline intensity between 2θ = 25–35° indicates the formation of a small amount of poorly crystalline hydration products. The reaction is driven by the slow activation of GGBS by the limited calcium and alkalinity in the loess pore solution. Calcium ions are mainly released from calcite dissolution and clay cation exchange sites, while slightly alkaline pore water provides OH⁻ ions for partial slag hydration. Under these mild conditions, GGBS gradually dissolves, releasing silicate (SiO₄4⁻) and aluminate (AlO₄5⁻) species that react with Ca2⁺ to form limited amounts of low-density, discontinuous C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels65. These gels primarily coat slag particles and loess grains, leading to minor XRD baseline broadening and modest mechanical improvement. On the other hand, as presented in Fig. 9, NS introduces a highly reactive amorphous silica source, which rapidly reacts with available Ca2⁺ from calcite and clay minerals. This pozzolanic reaction promotes early formation of C-S–H gels even without external calcium sources. NS particles also act as nucleation sites, facilitating gel precipitation around soil grains66. The resulting C-S–H fills pore spaces, improving particle bonding and reducing porosity. However, due to limited calcium in natural loess, the quantity and density of the C-S–H gels remain relatively low compared to systems with additional Ca-bearing materials.

When NS and GGBS are combined, a strong synergistic effect enhances cementation. GGBS supplies reactive CaO, SiO₂, and Al₂O₃, while NS improves the chemical environment and elevates pore solution pH, accelerating slag dissolution (Fig. 9). The liberated Ca2⁺, SiO₄4⁻, and AlO₄5⁻ species react rapidly with NS-derived silicates and alumina from loess clay minerals, forming abundant C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels. These gels fill interparticle voids, bind loess grains, and encapsulate unreacted slag particles. The resulting Ca/Si ratio is lower than in conventional cementitious systems due to the additional silica from NS, producing more polymerized and stable C-A-S–H structures. Incorporating Al further cross-links silicate chains, generating a dense and durable gel network65. The microstructure becomes continuous and low-porosity, with reduced pore connectivity and stronger particle interlocks, translating to higher UCS, lower permeability, and improved durability compared to GGBS-only treatments. In general, XRD and microstructural observations demonstrated that NS accelerates early gel formation via pozzolanic reactions but is constrained by calcium availability. Combining NS and GGBS leverages a synergistic mechanism, leading to rapid, dense gel formation, enhanced microstructural consolidation, and superior mechanical performance.

FTIR

Figure 10 presents the FTIR spectra of the untreated, 1% NS-treated, and 1% NS + 15% GGBS-treated. The untreated sample spectrum exhibits characteristic absorption bands, indicating various functional groups, with hydroxyl (OH) and water (H–O-H) vibrations observed at 3600–3200 cm⁻1, confirming the presence of surface hydroxyl groups and water molecules67. Carbonate (C-O) vibrations between 1400–1200 cm⁻1 suggest calcite or other carbonate minerals, while 1000 cm⁻1 bands correspond to silicate (Si–O/Si–O-Si) groups in clay minerals. The 1% NS treatment modifies the silicate band intensity and sharpness at 1000 cm⁻1. It represents the enhanced Si–O bonding and structural stabilization through surface reactions68, which correlates with the improvement in UCS. The combined 1% NS + 15% GGBS treatment induces significant spectral changes. Hence, reduced hydroxyl bands are revealed, demonstrating water consumption in hydration reactions and modified 1000 cm⁻1 regions reflecting complex silicate network formation. The FTIR spectra demonstrated notable differences among untreated, 1% NS-treated, and combined 1% NS + 15% GGBS-treated samples after 28 days of curing, indicating significant microstructural evolution. The reduction in hydroxyl bands and modifications in the silicate region confirm the consumption of water in hydration and pozzolanic reactions, with the formation of C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels. These spectral changes validate the enhanced soil stability, mechanical strength, and durability achieved through the synergistic effect of dual additives compared to the untreated samples.

SEM

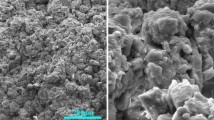

SEM analyses were conducted on the unstabilized loess soil samples, samples stabilized with NS, and those stabilized with NS + GGBS (Fig. 11). These analyses aimed to evaluate the effect of NS and the combined effect of NS and GGBS on loess soil stabilization. Unstabilized loess soil (Fig. 11a,b) exhibits greater porosity and no strong bonding between soil particles. The particles in this state are scattered without distinct cohesion, indicating the weak soil structure and a high likelihood of failure and erosion. The soil surface appears predominantly fine-grained with significant void space, a characteristic that renders loess soil highly susceptible to environmental changes. In Fig. 11c,d, with the addition of 1% NS, the soil particles become more cohesive, and the structure appears more compact. NS acts as a binding agent, enhancing particle interconnection, reducing porosity, and creating a more uniform structure. However, the existence of some voids indicates that this additive alone cannot establish fully robust bonding. Finally, Fig. 11e,f, showing the combination of NS with 15% GGBS, display a dense structure of soil particles. This combination forms a complex and continuous matrix, significantly enhancing the soil system’s resistance to deformation and degradation. With its cementitious properties, GGBS synergizes with NS to produce a compact, low-porosity structure, markedly improving the mechanical quality and stability of the soil. These results confirm the increased UCS, reduced CP, and enhanced durability of the sample stabilized with 1% NS and 15% GGBS compared to those stabilized solely with 1% NS or unstabilized samples.

This study employed a standard image analysis method using the ImageJ software (Version 1.54g; https://imagej.net) to calculate porosity69. Binary thresholding was determined using the Otsu algorithm70. The process was compared and calibrated with the data from previous reputable studies to ensure accuracy71. Image analysis results revealed porosity values of 15.4% for the unstabilized soil, 9.2% for the NS-stabilized soil, and 4.1% for the soil stabilized with NS and 15% GGBS. The interaction between NS and GGBS enhanced loess soil performance by combining their chemical and physical effects. NS increased reactive sites that promoted cementitious reactions and accelerated hardening, while GGBS supplied calcium compounds, forming strong C-S–H gels, leading to higher strength and stability. This synergy densified the soil matrix and refined the pore structure. SEM analyses confirmed a more compact microstructure with fewer microcracks in NS-GGBS-treated samples compared to the control, consistent with previous findings72.

Stabilization mechanisms

The stabilization mechanism included two main processes, as investigated in the microstructural results (BET, XRD, FTIR, and SEM). First, the chemical reaction of NS with water generated a three-dimensional silicate gel network that bound particles through hydrogen and siloxane bonds; hence, porosity was decreased while cohesion was enhanced. Second, NS particles bridged interparticle voids through localized densification, strengthening frictional forces and mechanical interlocking; thus, the bearing capacity was improved while permeability was reduced49,73. Concurrently, GGBS contributed through its high CaO, SiO₂, and Al₂O₃ contents, forming strength-enhancing C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels34,74. This pozzolanic process involved the dissolution of calcium and the breakdown of aluminosilicate components in GGBS-derived alkaline solutions, where bond cleavage facilitated the formation of C-S–H75. Subsequent silicon absorption promoted gel growth, while dissolved aluminum was incorporated into C-S–H frameworks at bridging sites, ultimately forming two/three-dimensional C-A-S–H gels34. As illustrated in Fig. 12, while C-S–H and C-A-S–H shared similar microstructures, C-A-S–H featured partial substitution of silicon tetrahedra by aluminum.

Sustainability aspects

This section discusses the benefits of using NS and GGBS together for stabilizing loess soil compared with conventional stabilizers, such as cement and lime, focusing on cost efficiency and environmental performance. The synergistic action between GGBS and NS improved the UCS up to 24 times that of the untreated soil, with only about 9% loss after several FTCs. Data related to cement and lime used in this study were collected from scientific sources76,77,78,79,80,81. Studies have shown that the highest compressive strength improvement for loess stabilized with cement and lime is approximately 9 and 5 times, respectively76,77. Economically, 1 ton of GGBS costs around 17 USD78; lime and cement prices are approximately 85 and 116.5 USD/ton79, respectively; and the cost of NS ranges from 0.35 to 0.75 USD/kg80,81. Given its low dosage and synergistic interactions with GGBS, NS has little effect on the overall cost, and its price continues to decline due to increasing demand and advancements in production technology. In contrast, conventional stabilizers impose heavy environmental burdens: producing one ton of lime releases 1.0–1.8 tons of CO282,83, whereas cement production emits about 1 ton of CO2/ton produced84,85. By comparison, generating 1000 kg of GGBS produces 40–70 kg of CO246,86, and NS production emits up to 1 kg of CO2/kg of the product80,87. Regarding embodied energy, values for GGBS, lime, and cement are approximately 1.1, 2.7, and 4.5MJ/kg, respectively, while NS requires around 15.9 MJ/kg.

Economically, stabilizing 1 ton of loess soil with GGBS + NS costs only 6.4 USD, compared with 6.88 USD for lime and 11.75 USD for cement, although its embodied energy (324 MJ) fell between lime and cement (200 and 400 MJ, respectively). The GGBS–NS blend emitted the least carbon, releasing only 18.25 kg compared to 70 and 75 kg for lime and cement. Figure 13 presents a normalized radar chart showing that the GGBS + NS blend outperformed cement and lime in three parameters, covering the largest performance area.

Practicality consideration

Stabilizing loess using a combination of NS and GGBS enhanced the engineering properties, thereby increasing the suitability for practical applications. Choosing the most effective stabilizer requires considering factors such as soil type, improvement technique, cost, and environmental impact88. The findings revealed that 1% NS with 15% GGBS can boost loess’s compressive strength relative to untreated samples, with minimal strength reduction even after repeated freeze–thaw stress. As highlighted in previous sections, this stabilization method also delivered tangible economic and ecological benefits. Enhanced mechanical properties and durability stemmed from the synergistic action of NS and GGBS, which promoted particle interaction and cement gel formation through pozzolanic reactions. This improvement reducing the necessary thickness of surface layers and consequently lowering construction costs.This approach is feasible for infrastructure projects, including road and airport subgrades. Accordingly, other researchers are encouraged to utilize CBR testing for loess treated with NS and GGBS when designing roadway and airport pavement systems.

Expanding the potential applications, this composite system can enhance the subgrade performance of slope stability and shallow foundations in loess regions. Mechanical performance tests in concert with microstructural analyses demonstrate a substantial increase in particle interaction and soil cohesion, which directly contribute to higher bearing capacity and improved settlement control. Such synergistic enhancement improves slope stability and subgrade behavior under shallow foundations. Additionally, in landfilling practices, where the external cover must resist erosion and comply with environmental standards89, the NS-GGBS blend decreases the permeability of loess soils by filling voids with cementitious gels—confirmed by BET and SEM analyses—thus allowing for reduced landfill liner thickness and overall cost savings.

Conclusion

This study investigated the synergistic combination of NS and GGBS for stabilizing loess soil. This combined treatment significantly enhanced the mechanical properties and FTC durability of the soil, while also providing a sustainable and cost-effective alternative to traditional stabilizers by reducing expenses and greenhouse gas emissions. The most important results of this research are as follows:

-

The optimal NS and GGBS contents modified the CP of the loess soil, shifting it from severe (CP ≈14.34) to slight (CP ≈1.65), representing an 88% improvement. These improvements were attributed to more uniform soil particle distribution, void filling, and enhanced cohesion in the soil matrix. BET test results corroborated these changes by showing a reduction in SSA and surface porosity in the stabilized soil.

-

The synergistic interaction between GGBS and NS, when combined for soil stabilization, led to the formation of dense, cementitious C-S–H and C-A-S–H gels. The UCS of soil stabilized with this GGBS-NS combination increased 24 times compared to untreated soil, whereas stabilization using lime and cement increased UCS only 5 times and 9 times, respectively. This combined GGBS-NS system improved soil stabilization performance and promoted sustainability by reducing energy consumption, lowering costs, and significantly cutting CO₂ emissions compared to traditional stabilization methods with cement or lime.

-

The repeated FTCs inducing localized weak zones significantly affected the constrained modulus of loess. In stabilized samples with optimal percentages of NS and GGBS, D decreased by only 9% after 10 FTCs, whereas this reduction was as high as 33% in unstabilized samples.

-

FTIR, SEM, and XRD results confirmed effective pozzolanic reactions in the stabilized specimens. Elevated silica and alumina ion concentrations promoted the extensive formation of cementitious compounds. SEM imaging revealed a dense and homogeneous matrix with well-dispersed NS particles, quantifying a reduction in soil mass void ratios to approximately 4%, which effectively inhibited the development of weak zones caused by thawing ice lenses.

This innovative stabilization approach represents an eco-friendly strategy, leveraging industrial waste utilization and reducing carbon emissions in geotechnical applications. However, the scope of this study was limited to a specific set of laboratory and environmental conditions. Moreover, curing at intervals of 90 days and one year is recommended to investigate the effect of long-term behaviors on the strength development and behavior of the stabilized soil. Future studies should investigate the chemical stability of stabilized soil in the presence of sulfates or acidic groundwater and the effects of successive wet-dry cycles and dynamic loads, considering longer curing periods. Besides, given that this stabilization method can increase soil brittleness, future research should focus on reducing this residual brittleness through the incorporation of fibrous reinforcements, supported by appropriate specialized testing.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arabani, M., Shalchian, M. M. & Majd Rahimabadi, M. The influence of rice fiber and nanoclay on mechanical properties and mechanisms of clayey soil stabilization. Constr. Build. Mater. 407, 133542 (2023).

Hatefi, M. H., Arabani, M., Payan, M. & Zanganeh Ranjbar, P. The influence of volcanic ash (VA) on the mechanical properties and freeze-thaw durability of lime kiln dust (LKD)-stabilized kaolin clayey soil. Results Eng. 24, 103077 (2024).

Guo, L. et al. Effect of modified materials on the hydraulic conductivity of loess soil. Sci. Rep. 15, 12340 (2025).

Kong, R., Zhang, F., Wang, G. & Peng, J. Stabilization of Loess using nano-SiO2. Materials 11, 1014 (2018).

Xu, L., Gao, C., Zuo, L., Liu, K. & Li, L. The critical states of saturated loess soils. Eng. Geol. 307, 106776 (2022).

Xie, W., Li, P., Zhang, M., Cheng, T. & Wang, Y. Collapse behavior and microstructural evolution of loess soils from the Loess Plateau of China. J. Mt. Sci. 15, 1642–1657 (2018).

Hatefi, M. H. et al. The role of particle shape in the mechanical behavior of granular soils: A state-of-the-art review. Results Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2024.103572 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Evaluation of soil quality and analysis of drivers of different vegetation patterns in the loess region of Northern Shaanxi. Sci. Rep. 15, 30496 (2025).

Dang, T. et al. Experimental research on the feasibility of phosphogypsum-enzyme induced carbonate precipitation (EICP) solidified loess. Sci. Rep. 15, 29683 (2025).

Liu, K., Ye, W. & Jing, H. Shear strength and microstructure of intact loess subjected to freeze‐thaw cycling. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. Prediction of loess collapsibility coefficient using bayesian optimized random forest model. Sci. Rep. 15, 25281 (2025).

Arabani, M., Shalchian, M. M. & Majd Rahimabadi, M. Use of wheat fiber and nanobentonite to stabilize clay subgrades. Results Eng. 24, 102931 (2024).

Boulebnane, M. A. et al. Optimizing mix design methods for using slag, ceramic, and glass waste powders in eco-friendly geopolymer mortars. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 25, 12 (2024).

Alshawmar, F. Utilization of nano silica and plantain leaf ash for improving strength properties of expansive soil. Sustainability 16, 2157 (2024).

Cheraghalikhani, M., Niroumand, H. & Balachowski, L. Micro- and nano-Illite to improve strength of untreated-soil as a nano soil-improvement (NSI) technique. Sci. Rep. 14, 10862 (2024).

Haeri, S. M., Soleymani Borujerdi, S. & Akbari Garakani, A. Effects of initial shear stress on the hydromechanical behavior of collapsible soils. Acta Geotech. 18, 6051–6076 (2023).

Iranpour, B. & Haddad, A. The influence of nanomaterials on collapsible soil treatment. Eng. Geol. 205, 40–53 (2016).

Haeri, S. M. & Valishzadeh, A. Evaluation of using different nanomaterials to stabilize the collapsible loessial soil. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 19, 583–594 (2021).

Ai, X., Luo, F., Ma, W., Qi, Y. & Zhu, Z. The study on the dynamic deformation characteristics of loess reinforced by nano-silica based on shakedown theory. Constr. Build. Mater. 458, 139546 (2025).

Orozco, C., Babel, S., Tangtermsirikul, S. & Sugiyama, T. Comparison of environmental impacts of fly ash and slag as cement replacement materials for mass concrete and the impact of transportation. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 39, e00796 (2024).

Hatefi, M. H., Arabani, M., Hosseinpour, I., Payan, M. & Zanganeh Ranjbar, P. The synergistic effect of nano-silica and calcium carbide residue on the mechanical properties and freeze-thaw durability of loess. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e05522 (2025).

Nan, J. et al. Investigation on the microstructural characteristics of lime-stabilized soil after freeze–thaw cycles. Transp. Geotech. 44, 101175 (2024).

Xie, B., Liu, Y. & Zhang, W. Reinforcement mechanisms of lignin fiber-stabilized loess: A multi-scale analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 491, 142624 (2025).

Li, G. et al. Engineering properties of loess stabilized by a type of eco-material, calcium lignosulfonate. Arab. J. Geosci. 12, 700 (2019).

Hatefi, M. H., Arabani, M., Payan, M. & Ranjbar, P. Z. Impact of recycled macro-synthetic fibers on kaolin soil stabilized with lime kiln dust and volcanic ash. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04830 (2025).

Hou, Y., Li, P. & Wang, J. Review of chemical stabilizing agents for improving the physical and mechanical properties of loess. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 80, 9201–9215 (2021).

Zanj, A. et al. Experimental study on freeze-thaw durability of high plasticity clay treated with waste glass powder and waste tire textile fibers. Results Eng. 27, 106221 (2025).

Zhang, P., Chou, Y., Peng, E. & Wang, Y. Swelling, mechanical strength, and curing mechanism of sulfate saline loess stabilized with MgO-GGBS binder. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-025-02685-w (2025).

Sun, H., Xie, M., Jia, L. & Xie, X. Mechanical characterization of Pb contaminated loess solidified/stabilized by red mud, ground granulated blast furnace slag and waste tire textile fibers. Environ. Geochem. Health 47, 294 (2025).

Guo, J., Jia, L., Wei, Z. & Zhang, L. Evaluation on the mechanical performance of lime–ground granulated blast-furnace slag stabilized loess. Arab. J. Geosci. 15, 1361 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. Experimental study on dry-wet durability and water stability properties of fiber-reinforced and geopolymer-stabilized loess. Constr. Build. Mater. 418, 135379 (2024).

Standard, A. D422–63 (2007) Standard test method for particle-size analysis of soils. ASTM Int. 10, 1520 (2007).

To, D., Sundaresan, S. & Dave, R. Nanoparticle mixing through rapid expansion of high pressure and supercritical suspensions. J. Nanopart. Res. 13, 4253–4266 (2011).

Salimi, M., Payan, M., Hosseinpour, I., Arabani, M. & Ranjbar, P. Z. Effect of glass fiber (GF) on the mechanical properties and freeze-thaw (F-T) durability of lime-nanoclay (NC)-stabilized marl clayey soil. Constr. Build. Mater. 416, 135227 (2024).

Shahsavani, S., Vakili, A. H. & Mokhberi, M. Effects of freeze-thaw cycles on the characteristics of the expansive soils treated by nanosilica and electric arc furnace (EAF) slag. Cold. Reg. Sci. Technol. 182, 103216 (2021).

Zhang, X. et al. Effects of particle size of colloidal nanosilica on hydration of Portland cement at early age. Adv. Mech. Eng. 11 (2019).

Bahmani, S. H., Huat, B. B. K., Asadi, A. & Farzadnia, N. Stabilization of residual soil using SiO2 nanoparticles and cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 64, 350–359 (2014).

Gu, J., Cai, X., Wang, Y., Guo, D. & Zeng, W. Evaluating the effect of nano-SiO2 on different types of soils: A multi-scale study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 16805 (2022).

ASTM D2166 (Standard test method for unconfined compressive strength of cohesive soil). American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken (2016).

Boz, A. & Sezer, A. Influence of fiber type and content on freeze-thaw resistance of fiber reinforced lime stabilized clay. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 151, 359–366 (2018).

ASTM. Test method for measurement of collapse potential of soils (ASTM D 5333–92). American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken https://doi.org/10.1520/D5333-92R96(1996)10.1520/D5333-92R96 (1996).

Zhang, Z., Hou, Y., Li, P. & Wang, J. Enhancement of geotechnical properties of loess using nano clay and nano-iron oxide. Environ. Earth Sci. 83, 418 (2024).

ASTM (2009) Standard test method for pulse velocity through concrete (ASTM C597). American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken (2009).

Mandal, T., Tinjum, J. M. & Edil, T. B. Non-destructive testing of cementitiously stabilized materials using ultrasonic pulse velocity test. Transp. Geotech. 6, 97–107 (2016).

Yuan, K., Li, Q., Ni, W., Zhao, L. & Wang, H. Graphene stabilized loess: Mechanical properties, microstructural evolution and life cycle assessment. J. Clean Prod. 389, 136081 (2023).

Singh, V. K. & Srivastava, G. Development of a sustainable geopolymer using blast furnace slag and lithium hydroxide. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 40, e00934 (2024).

Neelamegam, P. & Muthusubramanian, B. Evaluating embodied energy, carbon impact, and predictive precision through machine learning for pavers manufactured with treated recycled construction and demolition waste aggregate. Environ. Res. 248, 118296 (2024).

Liu, Z., Deng, Z., Davis, S. J. & Ciais, P. Global carbon emissions in 2023. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 253–254 (2024).

Chaudhary, V., Yadav, J. S. & Dutta, R. K. The impact of nano-silica and nano-silica-based compounds on strength, mineralogy and morphology of soil: A review. Indian Geotech. J. 54, 876–896 (2024).

Meeravali, K., Ruben, N. & Indira, M. Soil stabilization with nanomaterials and extraction of nanosilica: A review. in 293–300 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7827-4_29.

Solórzano-Blacio, C. & Albuja-Sánchez, J. Effect of nanosilica on the undrained shear strength of organic soil. Nanomaterials 15, 702 (2025).

Shalaby, O. B., Elkady, H. M., Salah, M., Nagy, N. M. & Fayed, A. L. Effect of kaolin-nano-silica mixture on geomechanical properties enhancement of soils. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 9, 384 (2024).

Barman, D. & Dash, S. K. Stabilization of expansive soils using chemical additives: A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 14, 1319–1342 (2022).

Latif, M. A., Naganathan, S., Razak, H. A. & Mustapha, K. N. Performance of lime kiln dust as cementitious material. Procedia Eng. 125, 780–787 (2015).

Arabani, M., Sadeghnejad, M., Haghanipour, J. & Hassanjani, M. H. The influence of rice bran oil and nano-calcium oxide into bitumen as sustainable modifiers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03458 (2024).

Changizi, F., Ghasemzadeh, H. & Ahmadi, S. Evaluation of strength properties of clay treated by nano-SiO 2 subjected to freeze–thaw cycles. Road Mater. Pav. Des. 23, 1221–1238 (2022).

Liu, X., Hou, P. & Chen, H. Effects of nanosilica on the hydration and hardening properties of slag cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 282, 122705 (2021).

Fu, Q., Zhao, X., Zhang, Z., Xu, W. & Niu, D. Effects of nanosilica on microstructure and durability of cement-based materials. Powder Technol. 404, 117447 (2022).

Goodarzi, A. R. & Salimi, M. Stabilization treatment of a dispersive clayey soil using granulated blast furnace slag and basic oxygen furnace slag. Appl. Clay Sci. 108, 61–69 (2015).

Vastrad, M., Karthik, M., Dhanavandi, V. & Shilpa, M. S. Stabilization of black cotton soil by using GGBS, lime and nano-silica. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. Manag. 3, 1–7 (2020).

Eissa, A., Ghazy, A., Bassuoni, M. T. & Alfaro, M. Improving the properties of soft soils using nano-silica, slag, and cement (2021) https://doi.org/10.11159/icgre21.lx.101.

Kalhor, A., Ghazavi, M., Roustaei, M. & Mirhosseini, S. M. Influence of nano-SiO2 on geotechnical properties of fine soils subjected to freeze-thaw cycles. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 161, 129–136 (2019).

Li, G. et al. Freeze-thaw resistance of eco-material stabilized loess. J. Mt. Sci. 18, 794–805 (2021).

Safdar, D., Farooq, K., Mujtaba, H., Shah, M. M. & Rehman, Z. U. Effect of density and surcharge pressure on collapse potential of loess soil treated with bagasse ash. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 50, 1665–1682 (2025).

Heirani, P. et al. Eco-friendly approach to clay stabilization: Integrating carbide lime, steel slag, and tire textile waste. J. Market. Res. 39, 2718–2741 (2025).

Provis, J. L. & Bernal, S. A. Geopolymers and related alkali-activated materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 44, 299–327 (2014).

Shalchian, M. M. et al. Sustainable construction materials: Application of chitosan biopolymer, rice husk biochar, and hemp fibers in geo-structures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04528 (2025).

Zimar, Z. et al. Use of industrial wastes for stabilizing expansive clays in pavement applications: durability and microlevel investigation. Acta Geotech. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-024-02298-9 (2024).

Oke, J. A. & Abuel-Naga, H. Durability assessment of eco-friendly bricks containing lime kiln dust and tire rubber waste using mercury intrusion porosimetry. Appl. Sci. 14, 5131 (2024).

Hapca, S. M., Houston, A. N., Otten, W. & Baveye, P. C. New local thresholding method for soil images by minimizing grayscale intra-class variance. Vadose Zone J. 12, 1–13 (2013).

Liu, K., Ye, W. & Jing, H. Multiscale evaluation of the structural characteristics of intact loess subjected to wet/dry cycles. Nat. Hazards 120, 1215–1240 (2024).

Chen, Q. et al. Improved mechanical response of Nano-SiO2 powder cemented soil under the coupling effect of dry and wet cycles and seawater corrosion. Acta Geotech. 19, 5915–5931 (2024).

Khodabandeh, M. A., Nagy, G. & Török, Á. Stabilization of collapsible soils with nanomaterials, fibers, polymers, industrial waste, and microbes: Current trends. Constr. Build. Mater. 368, 130463 (2023).

Borno, I. B., Haque, M. I. & Ashraf, W. Crystallization of C-S-H and C-A-S-H in artificial seawater at ambient temperature. Cem. Concr. Res. 173, 107292 (2023).

Salimi, M., Payan, M., Hosseinpour, I., Arabani, M. & Ranjbar, P. Z. Impact of clay nano-material and glass fiber on the efficacy of traditional soil stabilization technique. Mater. Lett. 360, 136046 (2024).

Gu, K. & Chen, B. Loess stabilization using cement, waste phosphogypsum, fly ash and quicklime for self-compacting rammed earth construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 231, 117195 (2020).

Kampala, A., Suebsuk, J., Sakdinakorn, R., Arngbunta, A. & Chindaprasirt, P. Coal-biomass fly ash as cement replacement in loess stabilisation for road materials. Int. J. Pav. Eng. 25, (2024).

Ma, Y., Chu, H., Rong, H. & Ba, M. Influence of sodium silicate on the properties of ground granulated blast furnace slag-desulfurized gypsum (GGBS-DG) based composite cementitious materials and LCA evaluation. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 46, 102066 (2025).

Fateh, S. et al. A comparison of temperature and freeze-thaw effects on high-swelling and low-swelling soils stabilized with xanthan gum. Results Eng. 25, 103719 (2025).

Du, Y., Korjakins, A., Sinka, M. & Pundienė, I. Lifecycle assessment and multi-parameter optimization of lightweight cement mortar with nano additives. Materials 17, 4434 (2024).

Swain, S. P. et al. An investigation of the mechanical strength, environmental impact and economic analysis of nano alkali-activated composite. J. Build. Eng. 97, 110922 (2024).

Simoni, M. et al. Decarbonising the lime industry: State-of-the-art. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 168, 112765 (2022).

Dowling, A., O’Dwyer, J. & Adley, C. C. Lime in the limelight. J. Clean Prod. 92, 13–22 (2015).

Komkova, A. & Habert, G. Environmental impact assessment of alkali-activated materials: Examining impacts of variability in constituent production processes and transportation. Constr. Build. Mater. 363, 129032 (2023).

Robayo-Salazar, R., Mejía-Arcila, J., Mejía de Gutiérrez, R. & Martínez, E. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of an alkali-activated binary concrete based on natural volcanic pozzolan: A comparative analysis to OPC concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 176, 103–111 (2018).

Liu, J., Wu, Y., Qu, F., Zhao, H. & Su, Y. Assessment of CO2 capture in FA/GGBS-blended cement systems: from cement paste to commercial products. Buildings 14, 154 (2024).

Joglekar, S. N., Kharkar, R. A., Mandavgane, S. A. & Kulkarni, B. D. Process development of silica extraction from RHA: A cradle to gate environmental impact approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 492–500 (2019).

Arabani, M., Shalchian, M. M. & Haghsheno, H. The impact of guar gum biopolymer on mechanical characteristics of soil reinforced with palm fiber. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 84, 30 (2025).

Venkata Vydehi, K., Moghal, A. A. B. & Basha, B. M. Reliability-based design optimization of biopolymer-amended soil as an alternative landfill liner material. J. Hazard Toxic Radioact. Waste 26 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (M.H.H. , M.A. , I.H. , M.P. , and P.Z.R. ) contributed equally to all aspects of the research and manuscript, Definition of the problem, Formal analysis, Validation, Supervision, Interpretation of the results, Investigation, writing paper (original draft),,including study design, data collection and analysis, drafting, writing (review and editing), Methodology, and revising the final version. Their collaboration was equally shared across all parts of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hatefi, M.H., Arabani, M., Hosseinpour, I. et al. Mechanical behavior and microstructural investigation of loess sustainable stabilization using nanosilica and GGBS. Sci Rep 16, 4187 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34210-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34210-0