Abstract

To investigate the influence of VUS on pregnancy outcome and fetuses. 132 VUS CNVs were identified in 3657 fetal amniotic fluid specimens by CNV-Seq. Parent-of-origin testing was subsequently analyzed to determine whether the CNV was inherited or de novo. Pregnancy outcomes of the pregnant women were tracked, and clinical assessments were performed to determine the evidence of any disease in the newborns between 1 and 2 years of age. Pregnant women with VUS in their fetuses were more likely to choose to continue with the pregnancy (105 out of 118, 88.98%). However, only a small number (2 out of 14, 14.29%) of pregnant women with de novo VUS chose to terminate the pregnancies. Additionally, out of the 115 live births, 3 fetuses carrying VUS were born with abnormalities, that could not be definitively linked to VUS. The majority of CNVs classified as VUS are likely to have non-disease outcomes in the fetuses. Therefore, it is important to establish a VUS fetal database, adopt dynamic tracking and follow-up. This will provide more powerful clinical evidence, based on the results of fetal ultrasound and the source of VUS; which will ultimately facilitate better clinical pregnancy management decisions and reduce anxiety for pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In China, the total incidence of birth defects is about 5.6%, resulting in around 900,000 new birth defects each year. As a result, the government places great emphasis on preventing and controlling birth defects, such as tertiary prevention measures1. With advancements in prenatal diagnostic technology, copy number variation sequencing (CNV-seq)2, and whole exome sequencing (WES)3 have emerged. CNV-Seq technology offers advantages such as high throughput, low DNA sample size, and high resolution4.

CNV-seq was used for sequencing analysis of samples, which based on next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology. By comparing the sequencing results with the human reference genome and CNV was found through bioinformatics analysis5. To ensure consistency and accuracy in the interpretation of CNV reports, the American Society for Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Society for Molecular Pathology (AMP) revised the criteria and guidelines for interpreting mutant sequences. The Standard and Guideline for Classification of ACMG Genetic Variation was published6. This standard classification system divides sequence variations into five categories: pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), uncertain significance (VUS), likely benign (LB), and benign (B), based on evidence analysis and weighted calculation. It also provides reference terms and variation classifications for laboratories6. In a study of 3429 amniocentesis samples, the cumulative frequency of chromosomal abnormalities identified through CNV-seq as pathogenic/likely pathogenic and uncertain significance variants was 2.83% and 1.43%, respectively2.When the clinical indication was an abnormal fetal ultrasound finding, the excess abnormality detection rate of 4.1% by microarray analysis over conventional karyotyping7; and the detection rate of variants of VUS was 2.1% (95% CI, 1.3–3.3%)7.

VUS represents a distinct category of CNVs, where there is generally no sufficient population data to definitively determine pathogenicity8,9. However, several reports have indicated that parent-of-origin studies could be highly beneficial in the clinical interpretation of fetal CNVs and possible pregnancy outcomes in such cases8,9,10. These studies have shown that most fetal VUS were inherited with no apparent evidence of abnormal birth outcomes. Nevertheless, genetic counseling remains difficult regarding continuation or termination of a pregnancy when parent of origin testing was rejected. Currently, there is limited research on fetal VUS. Further follow-up of births could help establish new genetic decisions and re-evaluate previous interpretations. A study of 3657 Chinese women using CNV-seq identified 132 cases of VUS and reported on the clinical decision-making process and postnatal outcomes of fetal VUS.

Methods

Subject

A total of 3657 expectant pregnant women who underwent amniocentesis and chromosome examination at the Department of Genetics and Prenatal Diagnosis, Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Luoyang from November 2020 to September 2023 were recruited to participate in the study. All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations in our study. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Luoyang Maternal and Child Health Hospital (LYFY-YCCZ-2020010). All pregnant women provided written informed consent for the genetic investigation of their pregnancy. The main indications for CNV-seq in pregnant women included: advanced age (≥ 35 years) (1157 cases, 31.64%), high risk based on serologic screening (1316 cases, 35.99%), ultrasound soft markers (712 cases, 19.47%), high risk for noninvasive testing (150 cases, 4.1%), adverse pregnancy history (165 cases, 4.51%), voluntary request (69 cases, 1.89%), and other factors such as genetic risk of monogenic diseases or abnormal amniotic fluid volume (88 cases, 2.4%). In cases where a VUS CNV was found in fetal testing, pregnant women were advised to undergo parent-origin testing to determine the source of the fetuses VUS.

Copy number variation sequencing (CNV-seq)

CNV-seq employs low-pass whole-genome sequencing to detect aneuploidies across all 23 chromosome pairs and identifies chromosomal abnormalities resulting from deletions or duplications (CNVs) exceeding 0.1 Mb within its detection range. According to Chen’s method11, parental peripheral blood samples and 3657 fetal amniotic fluid sample were prepared. CNV-seq was then performed as described previously. In summary, DNA was extracted and fragmented from the samples, and a DNA library was constructed through terminal filling, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. The DNA library was then subjected to large-scale parallel sequencing on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA), resulting in approximately 5 million raw sequencing reads with a genomic DNA sequence length of 36 base pairs. These reads were then compared with the human reference genome, and bioinformatics analysis was performed to obtain the sample’s genome copy number information. The reporting thresholds are set at deletions ≥ 100 Kb, duplications ≥ 200 Kb, and chromosomal aneuploidy mosaicism ≥ 10%. CNVs categorized as “benign” or “likely benign” are excluded from reports. Similarly, VUS are not reported if deletions are below 500 Kb or duplications below 1 Mb. Findings near the lower reporting limit may still be included when the affected genomic region is clinically relevant. These criteria were developed in accordance with the “Expert Consensus on Standardized Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Reporting of Copy Number Variants and Regions of Homozygosity in Prenatal Genetic Diagnosis”12. The clinical significance of CNVs was interpreted according to the “Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen)”6. This was done by consulting databases such as DGV (http://dgv.tcag.ca/), Decipher (https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk/), Clingen (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/dbvar/clingen/), OMIM (http://omim.org/), ISCA (http://dbsearch.clinicalgenome.org/search/), GeneCards (http://www.genecards.org/), UCSC (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) and ISCA (http://dbsearch.clinicalgenome.org/search/); published papers (such as CNKI: https://www.cnki.net; PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) or the laboratory internal database. In addition to the databases, guidelines, and literature described above, CNV interpretation must also incorporate clinical phenotype. A CNV can be classified as pathogenic when it aligns with the specific clinical presentation of the tested individual. Additionally, the pathogenicity of CNVs was initially classified into five categories based on a combination of fetal ultrasound results: pathogenic, likely pathogenic, VUS, likely benign, and benign.

Detection of parent-of-origin

When a fetal test shows a VUS, the clinician would advise the biological parents of the fetuses to undergo a CNV-seq test in order to identify the source of the fetal VUS. In some cases, there may be multiple CNVs in different regions of the genome. If the fetal VUS was inherited from parents with normal phenotype, the VUS was considered to be likely benign. In this study, CNV-seq was the sole method performed. The CNVs identified, especially those VUS classified as de novo, were not validated by independent techniques like qPCR or array CGH. Current guidelines do not recommend further testing to confirm de novo VUS findings6.

Follow-up of pregnancy outcome

Parents were followed up by telephone within 10 months after the birth of their children, and the follow-up continued until the children were 1–2 years old. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The questions asked during this follow-up included: any pregnancy complications, whether there was an abortion or termination of pregnancy (TOP) and the reason for it, the delivery date, method of delivery, newborn weight, and other developmental issues with the baby.

Results

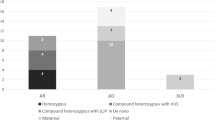

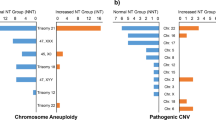

CNV analysis

Out of 3657 fetal samples, 303(8.29%)VUS CNVs and 120 (3.28%) P/LP CNVs were identified. In 132 cases (3.61%) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1), both parents were willing to undergo a parents-origin test to determine whether the fetal CNV was inherited from parents or was de novo. The gains (duplications) and losses (deletions) for the group of 132 VUS analyzed in this study are shown diagrammatically (Fig. 2). Of these cases, 116 (87.88%) were found to be inherited (52 maternal, 54 paternal, 10 paternal and maternal), 14 were de novo (10.61%), and 2 were both de novo and maternal (1.52%). The majority of pregnant women with inherited VUS chose to continue their pregnancy (105/118, 88.98%), while the remaining pregnancy outcomes were unknown due to the loss of follow-up. In the meanwhile, a small number (2/14, 14.29%) of pregnant women with de novo VUS chose to terminate their pregnancy, while the majority (10/14, 71.43%) chose to continue it. The details are as follows: In the first case, the pregnant woman was of advanced age and a 650 kb deletion was detected in the fetal 7q35 region (chr7: g.146625001_147275000del). Upon querying the DECIPHER database, one relevant case was matched [Decipher ID: 363535], the location was 7:146648785–147114287, with a segment size of 465.50 kb. The clinical manifestations included autism, with an unknown genetic origin. The classification of this CNV was VUS. In the second case, the pregnant woman was of advanced age and the abnormal non-invasive prenatal testing. A 5 Mb deletion was identified in the 1p21.1p13.3 region (chr1: g.104310001_109310000del). This CNV was classified as VUS, and it matched one related case [Decipher ID: 881] with unknown clinical manifestations and unknown genetic origin.

Characteristics of 132 VUS cases. Dot plots illustrate the size and type (gain or loss) of inherited or de novo VUS. Red dots represent VUS pregnancies that were terminated, while blue dots represent those with fetal ultrasound soft markers abnormalities. Orange dots indicate VUS pregnancies with loss of contact, and yellow dots represent those with abnormal birth. Black dots indicate VUS pregnancies with normal birth.

Pregnancy management decisions for inherited VUS fetuses

A clinical survey of 118 parents with fetal VUS revealed phenotypic characteristics that may indicate potential genetic disease. These characteristics suggest either subtle or variable disease penetrance, or no disease association at all for the VUS. Out of the 118 pregnancies included in the survey, the main clinical indications were 30 ultrasound soft markers abnormalities, 44 high-risk maternal serum screenings, 7 non-invasive high-risk procedures, 28 advanced maternal age (≥ 35 years), 4 maternal chromosomal abnormalities, and 5 adverse pregnancies (Fig. 3).

Results for 118 pregnancies with an inherited VUS are presented. (a) Outcomes for paternally inherited VUS pregnancies (n = 59), (b) Outcomes for maternally inherited VUS pregnancies (n = 59). (G) = gains; (L) = losses. The number of disrupted disease and non-disease genes for each VUS is also noted. The primary clinical indications for CNV-seq and the corresponding pregnancy outcomes are color-coded (see legend for reference).

During the telephone follow-up, 13 cases of inherited VUS were disconnected, and the remaining 105 pregnant women chose to continue the pregnancies. Of these, 3 cases of inherited VUS fetuses were found to have abnormalities after birth, while no association was observed between their clinical presentations and the inherited VUS they carried. In the first cases, ultrasonography revealed a choroid plexus cyst in the left lateral ventricle of the fetuses. After birth, the child was found to have nephroblastoma. In the second cases, the pregnant woman had a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Postnatal examination revealed abnormalities in the ocular fundus of the child. In the third case, the pregnant woman was of advanced age and had a history of poor pregnancy outcomes. The child was born prematurely and presented with conditions such as atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale. This lack of association may be attributed to two principal considerations: Firstly, some VUS likely represent polymorphic genetic variants unrelated to the primary clinical indication, particularly the major ultrasound abnormalities. In such cases, clinical counselors typically recommend further genetic testing, such as WES, to investigate other potential genetic causes. Secondly, although neither parent exhibited a disease phenotype, certain inherited VUS may display variable penetrance in the fetus, potentially leading to phenotypic expression after birth. Consequently, follow-up monitoring of these children remains advisable. The remaining 102 live births did not exhibit any detectable disease phenotypes or symptoms during the first 10 months of life.

Pregnancy management decisions for fetuses with de Novo VUS

14 fetuses with de novo VUS, 2 pairs of parents were disconnected and 2 pairs of parents chose to terminate the pregnancy (Fig. 4). In one case, fetal CNV-seq indicated a microdeletion of chromosome 7, with clinical manifestations including autism, and the family decided to terminate the pregnancy. In another case, the fetus CNV-seq results showed a 5 Mb deletion in the 1p21.1p13.3 region. The clinical manifestations were unknown, but the parents eventually chose to terminate the pregnancy. For de novo VUS, we integrate the primary clinical indications of the fetus with available clinical data to assess whether they exhibit strong, weak, or no correlation with the principal clinical manifestations of the pregnancy. When variants show no association with the observed phenotype, genetic counselors recommend that the couple undergo prenatal whole-genome or WES to identify other potential genetic causes. This approach, combined with the initial clinical indications such as abnormal ultrasound findings, facilitates a more informed final discussion of pregnancy management. The remaining 10 parents chose to continue the pregnancy, and the infants showed no detectable disease phenotypes or symptoms within the first 10 months after birth.

Discussion

According to the ACGM guidelines, the clinical significance of CNVs is divided into five levels: (1) pathogenic, (2) likely pathogenic, (3) VUS, (4) likely benign, and (5) benign. However, defining VUS poses difficulties for laboratory technicians and clinical genetic counselors, as these variants are influenced by new mutations, gene expression levels, and penetrance6. This study analyzed 3657 amniotic fluid specimens, identifying 303 (8.29%) with VUS, predominantly genetic duplications or deletions. Among the 132 cases with informed consent, the vast majority of fetuses (118 cases, 89.39%) inherited these CNVs from their parents, while 14 fetuses (10.61%) exhibited de novo VUS. Only a small number of pregnancies were terminated due to de novo VUS, and among those that continued, merely 2.27% of live births exhibited signs of disease within 1–2 years. However, a clear clinical phenotype for these VUS has not been reported. Therefore, parental verification of fetal VUS, identification of its origin, and further comprehensive family analysis combined with clinical auxiliary examinations could improve the interpretation of VUS reports, enhance clinical counseling, and support better pregnancy management decisions.

CNV-seq effectively detects chromosomal abnormalities, including microdeletions and microduplications that are often missed by traditional chromosome analysis13. This capability renders it a practical and reliable tool for diagnosing genetic disorders. A large prospective clinical study further confirmed the high reliability and accuracy of CNV-seq in identifying clinically significant fetal abnormalities within prenatal samples. Furthermore, CNV-seq increased the detection of pathogenic, likely pathogenic, or VUS findings by 1% over the expected yield from karyotyping2. In a separate analysis of 505 fetal samples, the incidence of chromosomal abnormalities was significantly higher in pregnant women aged ≥ 35 years than in younger individuals. The highest rate of pathogenic CNVs occurred in fetuses at ≤ 6 weeks of gestation (5.26%), whereas the incidence of VUS CNVs declined progressively with advancing gestational age14. It has also been observed that an increase in positive family history could predict the likelihood of VUS reclassification15. Although most VUS were ultimately reclassified as benign, one quarter were reclassified as pathogenic15. Consequently, regular assessment of VUS-associated risk based on family history and periodic reclassification checks are essential. All fetuses were followed up, and 88.98% (105/118) of those carrying a hereditary VUS were healthy and clinically asymptomatic after birth. However, clinical outcomes were unavailable for 13 fetuses. This indicates that the clinical outcomes of fetuses inheriting VUS from phenotypically normal parents are generally benign. Therefore, Parental validation provides critical evidence for interpreting VUS and substantially improves clinical counseling. Testing both parental and fetal samples later in gestation could clarify the clinical significance of fetal VUS and significantly shorten the validation timeline. These findings also expand existing genotype-phenotype databases, and we recommend further studies to directly assess the pathogenicity of these CNVs.

In conclusion, a limitation of this study is the insufficient duration of follow-up; extending observations to 2–4 years of age would have provided more informative data. Furthermore, clinical follow-up was incomplete for a subset of newborns due to loss of parental contact. The classification and interpretation of VUS remain challenging, particularly when they are detected during pregnancy. Most CNVs classified as VUS appear to have no clinical impact on newborn health, as demonstrated by follow-up studies of pregnancies carried to term. Determining the parent-of-origin for these variants is nevertheless essential. Parent-of-origin analysis provides valuable evidence for subsequent family testing and recurrence risk assessment, thereby offering more precise clinical guidance for frontline physicians. Additionally, a local CNV database dedicated to fetal VUS cases enables continuous monitoring and follow-up, which helps distinguish benign CNVs and systematically accumulate data on pathogenic and likely pathogenic CNVs. Such a database would offer robust clinical evidence to support pregnancy management decisions when a VUS is identified in the fetus.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Genome Sequence Archive repository in Original Genomics Database of Human Genetic (GSA: HRA010314) that are accessible at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/s/cp8ieIn2.

Abbreviations

- ACMG:

-

American Society for Medical Genetics and Genomics

- AMP:

-

Society for Molecular Pathology

- B:

-

Benign

- CNV-seq:

-

Copy number variation sequencing

- COP:

-

Continuation of pregnancy

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- G:

-

Gains

- LC:

-

Loss of contact

- L:

-

Losses

- LB:

-

Likely benign

- LP:

-

Likely pathogenic

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- P:

-

Pathogenic

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- TOP:

-

Termination of pregnancy

- VUS:

-

Unknown significance

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

References

Ministry of Health, People’s Republic of China. Report on prevention and treatment of birth defects (2012).

Wang, J. et al. Prospective chromosome analysis of 3429 amniocentesis samples in China using copy number variation sequencing. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 219(3), 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.05.030 (2018).

Petrovski, S. et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 393(10173), 758–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32042-7 (2019).

Liang, D. et al. Copy number variation sequencing for comprehensive diagnosis of chromosome disease syndromes. J. Mol. Diagn. 16(5), 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.05.002 (2014).

Lau, K. V., Douglas, N. P. O., Claus, K. H. & Estrid, V. H. Next generation sequencing technology in the clinic and its challenges. Cancers (Basel). 13(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13081751 (2021).

Riggs, E. et al. Technical standards for the interpretation and reporting of constitutional copy-number variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American college of medical genetics and genomics (ACMG) and the clinical genome resource (ClinGen). Genet. Med. 22(2), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0686-8 (2020).

Hillman, S. et al. Use of prenatal chromosomal microarray: prospective cohort study and systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 41(6), 610–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.12464 (2013).

Chen, L. et al. Influence of the detection of parent-of-origin on the pregnancy outcomes of fetuses with copy number variation of unknown significance. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 8864. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65904-2 (2020).

Mardy, A. et al. Variants of uncertain significance in prenatal microarrays: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG 128(2), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16427 (2021).

Panlai, S., Rui, L., Conghui, W. & Xiangdong, K. Influence of validating the parental origin on the clinical interpretation of fetal copy number variations in 141 core family cases. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 7(10). https://doi.org/10.1002/mgg3.944 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. Clinical efficiency of simultaneous CNV-seq and whole-exome sequencing for testing fetal structural anomalies. J. Transl Med. 20(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-021-03202-9 (2022).

Weiqiang, L. et al. [A consensus recommendation for the interpretation and reporting of copy number variation and regions of homozygosity in prenatal genetic diagnosis]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 37(7). https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2020.07.001 (2020).

Zhang, J. et al. Investigation on combined copy number variation sequencing and cytogenetic karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 21(1), 496. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03918-y (2021).

Wu, H., Huang, Q., Zhang, X., Yu, Z. & Zhong, Z. Analysis of genomic copy number variation in miscarriages during early and middle pregnancy. Front. Genet. 12, 732419. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.732419 (2021).

Wright, M. et al. Factors predicting reclassification of unknown significance. Am. J. Surg. 216(6), 1148–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.08.008 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants and the staff for their valuable contribution to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yanan Wang provided counseling to patients and designed the study. Yuqiong Chai, Jieqiong Wang and Yaxin Wang evaluated the CNVs to determine pathogenicity. Zhaohui Wang collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Pai Zhang made significant contributions in revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Luoyang Maternal and Child Health Hospital (LYFY-YCCZ-2020010).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Chai, Y. et al. Influence of copy number variation of unknown significance on the pregnancy outcomes. Sci Rep 16, 4079 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34227-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34227-5