Abstract

This study addresses a fundamental question in music psychology: which specific, dynamic acoustic features predict human listeners’ emotional responses along the dimensions of valence and arousal. Our primary objective was to develop and validate an interpretable computational model that can serve as a tool for testing and advancing theories of music cognition. Using the publicly available DEAM dataset, containing 1,802 music excerpts with continuous valence-arousal ratings, we developed a novel, theory-guided neural network. This proposed model integrates a convolutional pathway for local spectral analysis with a Transformer pathway for capturing long-range temporal dependencies. Critically, its learning process is constrained by established principles from music psychology to enhance its plausibility. A core finding from an analysis of the model’s attention mechanisms was that distinct acoustic patterns drive the two emotional dimensions: rhythmic regularity and spectral flux emerged as strong predictors of arousal, whereas harmonic complexity and musical mode were key predictors of valence. To validate our analytical tool, we confirmed that the model significantly outperformed standard baselines in predictive accuracy, achieving a Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) of 0.67 for valence and 0.73 for arousal. Furthermore, an ablation study demonstrated that the theory-guided constraints were essential for this superior performance. Together, these findings provide robust computational evidence for the distinct roles of temporal and spectral features in shaping emotional perception. This work demonstrates the utility of interpretable machine learning as a powerful methodology for testing and refining psychological theories of music and emotion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Music is a universal and profoundly influential feature of human culture, with a well-documented capacity to evoke affective experiences and express emotional meaning1,2,3,4. From the joyous anthems of celebration to the somber melodies of remembrance, the power of music to shape our inner world is undeniable. Yet, a fundamental scientific question persists: what are the precise underlying mechanisms that map complex, dynamic acoustic signals onto our subjective emotional experiences? Understanding this mapping process is not only a central goal of music psychology but also holds significant implications for the broader fields of affective science, neuroscience, and potential clinical applications2,5.

To systematically investigate this phenomenon, contemporary psychological science often conceptualizes emotion using dimensional models, with Russell’s circumplex model being a dominant framework in this domain6. Crucially, when modeling these dimensions, a theoretical distinction must be drawn between perceived emotion—the emotion recognized in the musical structure by the listener—and induced emotion—the subjective affective state felt by the listener7. While these two processes are often correlated, they are distinct psychological mechanisms. The present study, utilizing the DEAM dataset, specifically focuses on modeling perceived emotion. As detailed in the dataset’s benchmarking protocol, annotators were instructed to identify the emotion expressed by the music (“What do you think the overall arousal of this song is?“) rather than their own physiological or subjective state8. This framework has proven particularly valuable for computational research, as it provides a continuous and quantifiable target space for modeling the nuanced variations in emotional responses to music9,10. Building on this model, decades of music cognition research have established foundational links between specific acoustic features and these emotional dimensions. For instance, fast tempi and bright timbres are reliably associated with high arousal and positive valence, while slow tempi and minor modes are linked to low arousal and negative valence11,12,13.

While these findings provide an essential theoretical bedrock, the correlational methods often used to obtain them struggle to capture the non-linear, dynamic, and hierarchical nature of the music-emotion relationship10,14. Music is not a static collection of features but a structured process that unfolds over time, and our emotional responses are similarly dynamic, evolving as the piece progresses. The advent of deep learning offers a new kind of “computational microscope” capable of learning directly from complex acoustic representations and discovering patterns inaccessible to traditional methods. Within psychology, such models should be viewed not merely as engineering tools but as a methodological revolution, enabling researchers to analyze complex stimuli with unprecedented granularity and thus drive theoretical development15,16.

However, the power of these deep learning models is accompanied by a significant challenge for scientific inquiry: their “black box” nature, a well-recognized challenge in the field of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) that hinders trust and scientific progress17,18,19. A model that accurately predicts an emotional response but offers no insight into its decision-making process is of limited value for theory building. This “interpretability gap” is a fundamental barrier, as science progresses by constructing and testing falsifiable theories about underlying mechanisms. An unexplainable model is an untestable one; we cannot know if it operates on psychologically realistic principles or simply exploits statistical artifacts. For a computational model to contribute meaningfully to psychology, it must be interpretable, transforming it from a prediction engine into a computational instantiation of a psychological theory15,20. Only when a model can reveal which acoustic features influence emotion in what way can it be used to validate, refine, or challenge our existing scientific understanding.

To address this critical gap, the present study aimed to develop and test a theory-inspired, interpretable computational model to identify the specific, dynamic spectro-temporal features that predict listeners’ perceived valence and arousal in music. The core purpose was not merely to improve predictive accuracy, but to leverage the model’s interpretability to gain psychological insights into the mechanisms of the music-emotion map. Based on this objective, we formulated and tested three primary hypotheses:

-

1.

Predictive Validity (Hypothesis 1): We hypothesized that a hybrid model integrating local spectral features with long-range temporal dependencies would predict listeners’ valence and arousal ratings more accurately than baseline models relying on a single feature type.

-

2.

Interpretability and Psychological Plausibility (Hypothesis 2): We hypothesized that the model’s interpretability mechanisms would reveal distinct patterns of acoustic cues for valence and arousal, and that these patterns would be consistent with established findings in music psychology.

-

3.

Value of Theoretical Constraints (Hypothesis 3): We hypothesized that explicitly guiding the model’s learning process with a priori psychological knowledge would simultaneously improve its predictive accuracy and the psychological plausibility of its interpretations, compared to an unconstrained counterpart.

By testing these hypotheses, this study ultimately sought to determine if the emotional dimensions of valence and arousal are driven by distinct and acoustically separable sets of musical features, a proposition central to dimensional theories of emotion yet challenging to verify with traditional methods.

Materials and methods

Participants

The data for this study were sourced from the publicly available MediaEval Database for Emotional Analysis in Music (DEAM)8. The emotion ratings were originally collected from participants recruited via the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform21. According to the dataset’s documentation, the annotation density varied across the collection phases. For the 2013 and 2014 subsets, each excerpt was annotated by a minimum of 10 workers. However, for the 2015 subset, the number of annotators per song was reduced to five, although these workers were specifically recruited based on their performance consistency in previous tasks. While this recruitment strategy aimed to ensure data quality, the relatively low number of annotators per item—particularly in the 2015 set—represents a limitation. In affective computing, larger annotator pools are typically preferred to stabilize the high subjective variance inherent in emotional perception; thus, the “ground truth” values derived from these smaller groups may be more susceptible to individual biases than those in datasets with higher annotator density. Specific demographic information for the annotators, such as age, gender, or cultural background, was not provided with the dataset. The potential implications of this limitation, particularly regarding the sample’s generalizability, are addressed in the Discussion section.

Materials and apparatus

Musical stimuli

All musical stimuli were taken from the DEAM dataset, which comprises 1,802 music tracks in MP3 format (44.1 kHz sampling rate). The collection includes 1,744 45-second excerpts and 58 full-length songs, covering a diverse range of Western popular music genres (e.g., rock, pop, electronic, jazz), thus providing varied acoustic input for the model8.

Emotion annotation apparatus

The original emotion annotations were collected using a two-dimensional graphical interface where participants continuously rated the emotional content perceived in the music on the dimensions of valence and arousal while listening to the music8.

Procedure

The experimental procedure described here follows the protocol of the original DEAM dataset collection. Participants, recruited via MTurk, were presented with the musical stimuli through the online interface. They were instructed to move a cursor on a 2D grid to continuously report the perceived valence (x-axis) and arousal (y-axis) of the music in real-time. The annotation sampling rate was subsequently normalized to a uniform 2 Hz. To account for initial response latency and stabilization, the annotations corresponding to the first 15 s of each excerpt were excluded from the final analysis by the dataset’s creators. The resulting continuous time-series data for valence and arousal, scaled from − 1 to + 1, served as the dependent variables for our modeling task8,22.

Data analysis

Our data analysis strategy was designed to test the study’s three primary hypotheses. This involved (a) converting raw audio into a psychoacoustically plausible input representation, (b) developing and training our primary computational model (PVAN) along with several baseline models, and (c) evaluating the models based on both predictive performance and interpretability.

Audio feature representation

To prepare the audio for model input, raw waveforms were first converted into a time-frequency representation using the Constant-Q Transform (CQT)23. The CQT was chosen over the more common Short-Time Fourier Transform due to its logarithmic frequency resolution, which more closely aligns with human auditory perception and the tonotopic organization of the auditory cortex, making it a more psychologically grounded choice24.

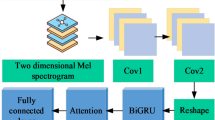

The PVAN computational model

To test our hypotheses, we developed the Psychologically Validated Attention Network (PVAN), an interpretable neural network designed for time-series analysis of music emotion. The overall architecture of the PVAN model is illustrated in Fig. 1. The model’s architecture consists of three key components:

-

Dual-Pathway Encoder: The model processes the CQT input through two parallel encoders. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) pathway captures local spectro-temporal patterns, which are analogous to perceptual features like timbre and texture25. A Transformer-based self-attention pathway models long-range temporal dependencies, analogous to the perception of musical form and narrative26.

-

Theory-Guided Constraint: A central innovation of the model is a regularization loss term, \(\:{L}_{\text{sensitivity\:}}\), designed to inject prior knowledge from music psychology into the training process. This “soft constraint” guides the model’s attention to align with theoretically important acoustic events without requiring manual annotations. This was operationalized by encouraging a positive correlation between the model’s attention weights, \(\:A\left(t\right)\), and the time-series of a pre-computed, theoretically relevant acoustic feature, \(\:{F}_{\text{guide\:}}\left(t\right)\). The selection of these guidance features adheres to the paradigm of Theory-Guided Data Science (TGDS), which advocates integrating established scientific knowledge into machine learning models to improve generalizability and interpretability27. Specifically, for the arousal dimension, we utilized rhythmic energy as the guidance feature. This choice is grounded in the “energy-arousal” link derived from physiological entrainment, and is empirically supported by Husain et al. (2002), who demonstrated a double dissociation where tempo manipulations selectively altered perceived arousal but not valence28. For the valence dimension, we utilized harmonic stability (chroma feature variance) to guide attention. This aligns with psychoacoustic theories positing that harmonic uncertainty and root ambiguity (characteristics of minor/complex chords) are the primary drivers of negative valence29. By embedding these robust psychological priors as inductive biases, the constraint effectively prunes the search space of biologically implausible solutions and mitigates the risk of the model learning spurious correlations from the limited training data. The loss is defined as: \(\:{L}_{\text{sensitivity\:}}=1-\text{c}\text{o}\text{r}\text{r}(A\left(t\right),{F}_{\text{guide\:}}\left(t\right))\).

-

Prediction Head: The features from both pathways are fused and fed into a final set of layers that output continuous predictions for valence and arousal over time.

Training and evaluation

A 5-fold cross-validation protocol was used for all model training and evaluation, with artist-level stratification to prevent data leakage. Model performance was primarily assessed using the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC)30, a stringent metric for continuous data agreement, defined as: \(\:\text{C}\text{C}\text{C}=\frac{2\rho\:{\sigma\:}_{x}{\sigma\:}_{y}}{{\sigma\:}_{x}^{2}+{\sigma\:}_{y}^{2}+{\left({\mu\:}_{x}-{\mu\:}_{y}\right)}^{2}}\). To test Hypothesis 1, the PVAN model was compared against three baseline models representing traditional (OpenSMILE feature-set)31, spectral-based (DeepSpectrum CNN)32, and temporal-based (Music Transformer) approaches33. To test Hypothesis 2 and 3, the trained PVAN model was subjected to interpretability analysis (via Grad-CAM) and a systematic ablation study34.

Results

This section presents the research findings objectively and concisely. All results are presented in the context of the research hypotheses, without subjective interpretation.

Hypothesis 1: predictive performance of PVAN

To test the first hypothesis (H1)—that a hybrid spectro-temporal model would outperform unimodal baseline models—the predictive performance of PVAN was compared with the three baseline models. As shown in Table 1, the PVAN model achieved the highest Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) scores for both valence and arousal prediction. The proposed model demonstrates a clear and statistically significant improvement over all baseline approaches (all paired t-tests, p <.001). Notably, the performance gain is more pronounced compared to the traditional hand-crafted feature model, highlighting the advantage of deep feature learning.

These results provide strong support for Hypothesis 1, indicating that an architecture integrating both local spectral information and long-range temporal dependencies is superior for modeling the music-emotion relationship.

Hypothesis 2: interpretable feature analysis

To test our second hypothesis (H2)—that the model would identify distinct and psychologically plausible acoustic drivers for valence and arousal—we employed Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to visualize the model’s internal feature importance.

Figure 2 provides a qualitative visualization of these learned patterns for two illustrative musical excerpts. As depicted in Fig. 2a, for a high-arousal prediction on a rock excerpt, the model’s attention (indicated by the heatmap) is concentrated on the sharp, vertical spectro-temporal transients. These visual patterns correspond to the acoustic impact of drum hits, which are proxies for features like high Tempo and Spectral Flux. Conversely, as shown in Fig. 2b, when making a low-valence prediction for a classical excerpt, the model focuses its attention on the stable, horizontal harmonic structures of the sustained cello and piano notes. These patterns are acoustic representations of low Harmonic Complexity.

These visualizations provide initial qualitative support for H2, suggesting that the model indeed learns to focus on different types of acoustic events for arousal and valence predictions. To formally quantify these observations, we conducted a multiple regression analysis. For each musical excerpt, we regressed the model’s aggregated attention weights for a given prediction (e.g., high arousal) onto a set of standard, interpretable acoustic features extracted using the librosa library35.

Table 2 presents the standardized beta coefficients (β) from this analysis. The quantitative results reveal a clear dissociation in the feature patterns, corroborating our qualitative observations from Fig. 2. As hypothesized, arousal was most strongly predicted by features related to time and energy, such as Tempo (β = 0.55, p <.001) and Spectral Flux (β = 0.48, p <.001). This statistically confirms the pattern observed in Fig. 2a. In contrast, valence was most strongly and negatively predicted by Harmonic Complexity (β = − 0.43, p <.001), which aligns with the model’s focus on stable harmonic structures for the low-valence excerpt in Fig. 2b. These findings are highly consistent with the established music psychology literature and provide strong quantitative support for Hypothesis 211,12.

Hypothesis 3: ablation study of model components

To test the third hypothesis (H3)—the importance of theoretical constraints—an ablation study was conducted by systematically removing key components from the full PVAN model and evaluating the resulting performance degradation. The results are shown in Table 3.

The results clearly demonstrate the contribution of each component. Removing the psychological constraint resulted in the most substantial performance degradation for both valence (ΔCCC = −0.09) and arousal (ΔCCC = −0.11), underscoring its critical role. This finding strongly supports Hypothesis 3. Furthermore, removing either the temporal or spectral pathway also significantly impaired performance, confirming their complementary importance and justifying the hybrid dual-pathway design.

Discussion

This study sought to deconstruct the complex mapping between music’s acoustic features and human emotional perception by developing and validating an interpretable computational model. Our results successfully demonstrated that a hybrid neural network, guided by principles from music psychology, can accurately predict dynamic emotional responses in terms of valence and arousal. The central finding of this research is the clear dissociation of acoustic cues driving these two emotional dimensions: the model’s interpretable analysis revealed that temporal and timbral-flux features (e.g., tempo, spectral flux) are primary drivers of arousal, while harmonic and tonal features (e.g., harmonic complexity, modality) are the principal drivers of valence. As hypothesized, the model’s hybrid architecture outperformed simpler baselines (H1), its interpretations were consistent with established psychological theory (H2), and the inclusion of a theory-guided constraint was critical to its success (H3). These findings offer not only a robust predictive model but also significant theoretical and methodological contributions to the study of music and emotion.

Theoretical implications for music psychology

The findings of this study are not merely about the performance of a computational model; more importantly, they provide computational evidence for psychological theories, which is the core contribution of this research to the field of psychology.

First, the results of the ablation study (Table 3) provide strong computational evidence for multi-pathway processing theories in music perception. The finding that removing either the spectral pathway (CNN) or the temporal pathway (Transformer) leads to a significant drop in performance suggests that emotion perception is not a monolithic process. It appears to depend on the parallel processing of timbre/texture (captured by the spectral pathway) and musical structure/form (captured by the temporal pathway). This finding resonates with theories that advocate for music cognition as a multifaceted, multi-level process and provides a computational instantiation for these theories36,37.

Second, one of the most significant findings of this study is that constraining the model with our proposed Theory-Guided Feature Sensitivity Constraint (Hypothesis 3) greatly enhances its performance. This result has profound theoretical implications. It provides strong computational evidence for the “theory-driven” nature of human music perception. The results show that a purely data-driven model (the unconstrained version) performs poorly, whereas the model’s overall performance improves significantly when it is guided to focus on acoustically relevant cues that are already known to be psychologically important (like rhythmic energy). This provides a computational instantiation of ‘top-down processing’ in cognitive psychology38,39. Our model does not passively receive acoustic information; rather, it more effectively parses emotion-related structures from the complex signal stream under the guidance of a “prior expectation.” This offers a novel, operationalized computational validation pathway for frameworks like Predictive Coding and Expectation Theory in the music domain40,41,42,43.

Finally, the analysis of interpretable features (Table 2) provides quantitative support for many long-standing but often qualitative observations in music theory. For example, the model found that rhythm is a primary driver of arousal, while harmonic complexity and minor-mode characteristics strongly influence valence. These findings not only validate the psychological plausibility of the model but also precisely describe the relative importance of these features through quantitative measures (such as specific regression coefficients), providing an empirical basis for the future refinement of theory.

Methodological contribution: interpretable AI as a tool for theory Building

In addition to its theoretical implications, this study provides a methodological paradigm for how interpretable artificial intelligence (AI) can be used for theory building and testing in psychology15,44. Traditionally, computational models in psychology have been used either as simplified “simulations” or as purely predictive tools. This study demonstrates a third way: designing complex AI models as testable, formalized systems to instantiate and test psychological theories.

By linking the model’s architecture to psychological processes (like parallel processing) and its constraints to theoretical knowledge (like prior expectations), this study transforms an engineering tool into a scientific instrument. Its value is no longer just in the accuracy of its predictions (“what”), but in the explanations it provides (“how” and “why”). This methodology holds promise for application in other areas of psychology where research involves complex stimuli and dynamic responses, which could benefit from this interpretable modeling approach.

Limitations and future directions

Scope of emotional modeling

It is important to acknowledge the distinction between the acoustic encoding of emotion and the subjective experience of the listener. The ground truth labels in the DEAM dataset reflect perceived emotion—the consensus on what the music expresses—rather than induced emotion (what the listener feels). While prior research suggests a strong link between the two, particularly for basic emotions, they can dissociate due to individual differences in personality, mood, or listening context7. Therefore, the “drivers” identified by our model (e.g., rhythmic regularity for arousal) should be interpreted as the acoustic cues that convey emotional expression in the signal, which act as the stimulus for, but are not identical to, the felt emotional response. This distinction is particularly relevant given the nature of the musical stimuli used in this study.

Dataset and stimuli limitations

Although the DEAM dataset is large, its composition imposes specific constraints on generalizability. The musical stimuli were primarily harvested from royalty-free repositories (e.g., Jamendo, Free Music Archive) and research-oriented multitrack collections (MedleyDB), which are frequently used as background music for video content or commercial environments8. This functional nature differs from commercially produced popular music designed for active engagement and strong emotional induction. Furthermore, the data collection protocol necessitated a highly unusual mode of listening: participants were required to actively self-monitor and continuously report their emotional perception. This dual-task paradigm imposes a cognitive load that diverges from the holistic nature of naturalistic music consumption, potentially prioritizing analytical processing over immersive emotional experience14. Consequently, the resulting annotations may be biased towards salient, bottom-up acoustic features (such as sudden rhythmic changes or loudness) that are easier to track in real-time. Another critical factor is the obscurity of the artists in the DEAM dataset. While using unknown music offers the methodological advantage of minimizing confounding effects from prior exposure or specific autobiographical associations, it simultaneously eliminates a potent mechanism of emotional induction: familiarity. Research in music neuroscience has established that familiarity enhances emotional engagement through predictive processing and episodic memory45. By relying on unfamiliar stimuli, our model effectively isolates bottom-up, acoustic-driven emotional perception but may overlook the top-down, memory-driven affect that characterizes real-world listening experiences. Beyond familiarity, the temporal integrity of the musical stimuli is also compromised by the dataset’s construction. The excerpts were randomly cropped, often removing natural onsets (introductions) and cadences (endings)8. In music cognition, these structural boundaries are critical for establishing expectation and providing resolution—key mechanisms of emotional induction41,46. The absence of complete narrative arcs presents a challenge for the Transformer pathway, which is designed to model long-range dependencies, and potentially limits the model’s ability to capture emotion driven by macro-structural form47. Finally, the annotations rely on MTurk crowdsourced participants who may lack demographic diversity. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be directly generalizable to other cultures or musical traditions. It is a well-known fact that the emotional perception of music is heavily influenced by cultural background48,49.

Model limitations

While the model’s architecture is psychologically inspired, it is just one of many possibilities. In particular, the “Theory-Guided Feature Sensitivity Constraint” we employed, while effective, may itself introduce a degree of confirmation bias. By pre-selecting guidance features based on existing theories (e.g., rhythm is important for arousal), we may bias the model to “rediscover” relationships we already know, while ignoring or suppressing novel feature-emotion associations that are not yet fully explained by current theories50. A true breakthrough might lie precisely in those patterns that are “inconsistent” with existing theories.

Future directions

Based on these limitations, future research could proceed in several directions. First, applying this modeling approach to cross-cultural datasets could test the extent to which the acoustic-emotion mappings found in this study are universal. Additionally, to address the ecological validity concerns regarding the musical stimuli, future work should validate the model on datasets comprising commercially released recordings or live performances, ensuring that the identified features generalize to music designed for active emotional engagement. Second, future models could attempt to integrate individual listener difference data (such as personality traits, musical training background, familiarity with the stimuli, and current mood state). Crucially, incorporating these listener-centric variables would allow researchers to move beyond modeling perceived emotion (as in the current study) to predicting the truly subjective induced emotional response of the individual listener. Finally, extending the model to process longer musical excerpts or complete works would overcome the structural fragmentation of the current dataset, allowing for a deeper investigation into the impact of long-range musical narrative on emotion.

Conclusion

This study successfully deconstructed the complex relationship between music’s acoustic properties and human emotion by developing and validating a novel, interpretable computational model. Our primary contribution is the robust computational evidence demonstrating that the core emotional dimensions of valence and arousal are driven by distinct and separable sets of acoustic features. Specifically, we found that temporal and timbral-flux characteristics primarily govern arousal, while harmonic and tonal properties predominantly shape valence. This was achieved by introducing a new methodology where a psychologically-guided neural network serves not as a “black box” predictor, but as a transparent scientific instrument for testing and refining psychological theory. By bridging the gap between data-driven machine learning and theory-driven cognitive science, this work paves the way for a more precise, empirically-grounded understanding of one of humanity’s most profound experiences: the emotional power of music.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the MediaEval Database for Emotional Analysis in Music (DEAM) at https://cvml.unige.ch/databases/DEAM/.

References

Juslin, P. N. & Sloboda, J. Handbook of Music and Emotion: Theory, research, Applications (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Koelsch, S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15 (3), 170–180 (2014).

Hou, J. et al. Review on neural correlates of emotion regulation and music: implications for emotion dysregulation. Front. Psychol. 8, 501 (2017).

Chong, H. J., Kim, H. J. & Kim, B. Scoping review on the use of music for emotion regulation. Behav. Sci. 14 (9), 793 (2024).

Juslin, P. N. Musical Emotions Explained: Unlocking the Secrets of Musical Affect (Oxford University Press, 2019).

Russell, J. A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 39 (6), 1161 (1980).

Gabrielsson, A. Emotion perceived and emotion felt: same or different? Musicae Sci. 5 (1_suppl), 123–147 (2001).

Aljanaki, A., Yang, Y. H. & Soleymani, M. Developing a benchmark for emotional analysis of music. PloS One. 12 (3), e0173392. (2017).

Kim, Y. E. et al. Music emotion recognition: A state of the art review. In Proc. ismir (Vol. 86, pp. 937–952). (2010), August.

Han, D., Kong, Y., Han, J. & Wang, G. A survey of music emotion recognition. Front. Comput. Sci. 16 (6), 166335 (2022).

Eerola, T. & Vuoskoski, J. K. A comparison of the discrete and dimensional models of emotion in music. Psychol. Music. 39 (1), 18–49 (2011).

Juslin, P. N. & Laukka, P. Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: different channels, same code? Psychol. Bull. 129 (5), 770 (2003).

Ilie, G. & Thompson, W. F. A comparison of acoustic cues in music and speech for three dimensions of affect. Music Percept. 23 (4), 319–330 (2006).

Schubert, E. Modeling perceived emotion with continuous musical features. Music Percept. 21 (4), 561–585 (2004).

Guest, O. & Martin, A. E. How computational modeling can force theory Building in psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 16 (4), 789–802 (2021).

Barrett, L. F. The theory of constructed emotion: an active inference account of interoception and categorization. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 12 (1), 1–23 (2017).

Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1 (5), 206–215 (2019).

Adadi, A. & Berrada, M. Peeking inside the black-box: a survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). IEEE access. 6, 52138–52160 (2018).

Samek, W., Montavon, G., Lapuschkin, S., Anders, C. J. & Müller, K. R. Explaining deep neural networks and beyond: A review of methods and applications. Proceedings of the IEEE, 109(3), 247–278. (2021).

Mahmoodi, J., Leckelt, M., van Zalk, M. W., Geukes, K. & Back, M. D. Big data approaches in social and behavioral science: four key trade-offs and a call for integration. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 18, 57–62 (2017).

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T. & Gosling, S. D. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality data? (2016).

Soleymani, M., Aljanaki, A. & Yang, Y. DEAM: Mediaeval Database for Emotional Analysis in Music (Geneva, 2016).

Brown, J. C. Calculation of a constant Q spectral transform. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 89 (1), 425–434 (1991).

Schörkhuber, C. & Klapuri, A. Constant-Q transform toolbox for music processing. In 7th sound and music computing conference, Barcelona, Spain (pp. 3–64). SMC. (2010), July.

LeCun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE. 86 (11), 2278–2324 (2002).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems vol. 30. 5998–6008 (2017).

Karpatne, A. et al. Theory-guided data science: A new paradigm for scientific discovery from data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 29 (10), 2318–2331 (2017).

Husain, G., Thompson, W. F. & Schellenberg, E. G. Effects of musical tempo and mode on arousal, mood, and Spatial abilities. Music Percept. 20 (2), 151–171 (2002).

Parncutt, R. The emotional connotations of major versus minor tonality: one or more origins? Musicae Sci. 18 (3), 324–353 (2014).

Lawrence, I. & Lin, K. A Concordance Correlation Coefficient To Evaluate Reproducibility 255–268 (Biometrics, 1989).

Eyben, F., Wöllmer, M. & Schuller, B. Opensmile: the munich versatile and fast open-source audio feature extractor. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 1459–1462). (2010), October.

Cummins, N. et al. An image-based deep spectrum feature representation for the recognition of emotional speech. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 478–484). (2017), October.

Huang, C. Z. A. et al. (2018). Music transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.04281.

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision (pp. 618–626). (2017).

McFee, B. et al. Librosa: audio and music signal analysis in python. SciPy 2015, 18–24 (2015).

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 (5), 393–402 (2007).

Koelsch, S. Toward a neural basis of music perception–a review and updated model. Frontier Psychol. 2, 110 (2011).

Gregory, R. L. The intelligent eye. (1970).

Bar, M. Visual objects in context. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5 (8), 617–629 (2004).

Meyer, L. B. Emotion and Meaning in Music (University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Huron, D. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation (MIT Press, 2008).

Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behav. Brain Sci. 36 (3), 181–204 (2013).

Koelsch, S., Vuust, P. & Friston, K. Predictive processes and the peculiar case of music. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23 (1), 63–77 (2019).

Montague, P. R., Dolan, R. J., Friston, K. J. & Dayan, P. Computational psychiatry. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 (1), 72–80 (2012).

Pereira, C. S. et al. Music and emotions in the brain: familiarity matters. PloS One. 6 (11), e27241. (2011).

Gabrielsson, A. & Lindström, E. The role of structure in the musical expression of emotions. Handbook of music and emotion: Theory, research, applications, 367400, 367 – 44. (2010).

Wingstedt, J. Narrative music: towards an understanding of musical narrative functions in multimedia (Doctoral dissertation, Luleå tekniska universitet). (2005).

Balkwill, L. L. & Thompson, W. F. A cross-cultural investigation of the perception of emotion in music: psychophysical and cultural cues. Music Percept. 17 (1), 43–64 (1999).

Swaminathan, S. & Schellenberg, E. G. Current emotion research in music psychology. Emot. Rev. 7 (2), 189–197 (2015).

Nickerson, R. S. Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2 (2), 175–220 (1998).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G. and C.S. contributed equally to this work. Y.G. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology, implemented the software, and wrote the original draft. C.S. acquired the funding, performed validation of the experimental results, and contributed significantly to the writing, review, and editing of the manuscript. Y.F. assisted with data curation and visualization. J.L. provided supervision, project administration, and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, Y., Shao, C., Li, J. et al. Interpretable deep learning reveals distinct spectral and temporal drivers of perceived musical emotion. Sci Rep 16, 4205 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34238-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34238-2