Abstract

In the digital age, patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are exposed to extensive health information, leading to information overload (IO). This overload results in decision-making difficulties, increased cognitive burden, and reduced health literacy (HL). This study investigates the complex relationship among IO, cognitive fusion (CF), and HL, emphasizing the moderating role of CF. A cross-sectional survey was conducted involving 233 patients with T2DM. Participants completed a general information questionnaire, the Information Overload Scale (IOS), the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ), and the Diabetes Health Literacy Scale (DHLS). A moderated network analysis was used to explore the bidirectional associations between IO and HL and to verify the moderating effect of CF. Network analysis revealed several significant bidirectional relationships between IO and HL, with CF showing a significant moderating effect. Reduced CF strengthened the positive effects of “perceived diabetes information overload” and “multi-channel diabetes information stress” on “functional health literacy”, as well as the effect of “increased diabetes information device maintenance” on “interactive health literacy”. “perceived diabetes information overload” had the highest centrality index in the network model, which demonstrated overall good stability. This study advances understanding of the relationships among IO, CF, and HL in patients with T2DM. The findings suggest that interventions aimed at alleviating cognitive rigidity should adopt comprehensive strategies targeting the IO symptom network to enhance HL in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic metabolic disease with high global prevalence. Approximately 536.6 million adults worldwide currently have T2DM, and this number is projected to increase to 783.2 million by 20451. With the increasing prevalence of T2DM, morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes and its complications remain high, imposing a significant economic burden2. With the increasing prevalence of T2DM, morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes and its complications remain high, imposing a significant economic burden. And effective management largely depends on patients’ health literacy (HL)3. HL refers to an individual’s ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate healthcare decisions4. However, studies have shown that HL levels among T2DM patients are generally low5, leading to decreased treatment adherence, poor blood glucose control, and increased complication risk. In addition, increasing evidence indicates a positive correlation between HL and quality of life in patients with T2DM6. Given that diabetes self-care relies predominantly on printed materials and oral instructions, patients with T2DM undoubtedly require sufficient HL.

T2DM management relies on patients’ long-term understanding and application of complex medical information, including drug therapy, blood glucose monitoring, dietary control, and complication prevention7. The digital age exposes patients to massive amounts of health information, often exceeding their processing capacity and resulting in information overload (IO)8. IO refers to a phenomenon wherein patients encounter health information exceeding their processing capacity, increasing cognitive burden and impairing decision-making ability. IO is a subjective perception influenced not only by information characteristics but also by individuals’ maladaptive information-use behaviors. IO may prompt patients to question the authenticity of health information and selectively attend to key details, causing cognitive difficulties and information avoidance behaviors9. Studies have demonstrated that excessively high IO levels diminish patients’ confidence, motivation, and ability to manage their health effectively10. HL encompasses functional, interactive, and critical literacy, with information discernment being a crucial factor in enhancing HL11. In addition, research confirms that T2DM patients with low HL experience greater difficulty and IO during health information acquisition12. Therefore, a complex and multifaceted intrinsic relationship exists between IO and HL, warranting a more comprehensive understanding to provide new intervention perspectives for improving HL among patients with T2DM.

Cognitive fusion (CF) refers to excessive identification with one’s thoughts, leading to behavioral restriction and reduced awareness of reality13. Systematic reviews and meta analyses consistently show a close association between T2DM and poorer cognitive ability14. At the same time, the continuous fluctuation of blood glucose can directly damage the cognitive function of the brain15. CF can promote negative behaviors and thinking patterns, such as ineffective actions, excessive attention, and feeling of demoralization. A longitudinal study confirmed a positive correlation between CF and social anxiety, while social support networks serve as a critical protective factor in accessing health information16. Therefore, we speculate that psychological rigidity may negatively impact HL in T2DM patients. Furthermore, studies have indicated that excessive disease-related information, when coupled with anxiety and depression, can deplete the cognitive resources of patients with type 2 diabetes, exceeding their cognitive capacity and leading to cognitive rigidity17. Research also suggests that improving cognitive flexibility serves as a key strategy to mitigate information overload18. Although there is evidence indicating a strong interrelationship among IO, CF, and HL in T2DM, these analyses have mainly adopted macro-level correlation methods. The micro-level interactions and node-specific dynamics within these relationships have rarely been explored. In particular, studies targeting the T2DM population are notably lacking. Therefore, this study employs moderated network analysis to explore the association among these three variables at the symptom level. This analytical method differs from traditional mediation models and is particularly suitable for clarifying the interrelationships between symptoms19. We use moderated network analysis to examine the moderating effect of CF on the relationship between IO and HL.

Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses: (1) H1: There is a bidirectional association between IO and HL in patients with T2DM; (2) H2: CF moderates the association between IO and HL.

Theoretical framework

According to Bandura’s social cognitive theory20, which centers on triadic reciprocal determinism, an individual’s cognition, behavior, and environment interact continuously and collectively shape human development. This framework offers a unified cognitive‑behavioral mechanism through which research hypotheses can be examined. Within this model, HL is conceptualized as the behavioral capacity to efficiently process health information; IO represents an environmental factor in which external informational demands exceed an individual’s available cognitive resources; and CF functions as a maladaptive personal cognitive factor that undermines individual agency. The core risk posed by CF lies in its persistent erosion of patients’ self‑efficacy.

Under conditions of IO, individuals with high CF may catastrophize the objective situation of excessive information, interpreting it as evidence of personal incompetence. This perception may trigger intense anxiety, deplete cognitive resources, and significantly intensify the negative impact of IO on HL21.

Methods

Design

This single-center, cross-sectional study was conducted at Panyu Health Management Center in Guangzhou, China. Ethical approval for this study was secured from the Medical Ethics Committee of the Panyu District Health Management Center, in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (Approval No. PYJKZX-LY-202512, dated August 17, 2024). Informed consent was provided by all participants.

Study setting and sample

The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cross-sectional studies. Valid questionnaires were returned by 233 participants, yielding a response rate of 90.6%. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥ 18 years and a confirmed T2DM diagnosis. Exclusion criteria included previous mental disorders that precluded cooperative treatment and concurrent severe organic diseases affecting vital organs. Network parameters were estimated using Pairwise Markov Random Fields (PMRF)22. There are 12 nodes in our network model (including 8 items of IOS, 3 dimensions of DHLS, and single-dimensional CFQ), requiring the estimation of 12 threshold parameters and 66 pairwise association parameters ([12 × (12 − 1)]/2), totaling 78 parameters. In addition, the sample size required for network analysis is based on 5–6 samples per node22. Given that the current network includes 12 nodes, at least 45 participants are needed. Considering a 20% attrition rate, the recommended minimum sample size is 83 participants. Our sample (n = 233) provides sufficient power for stable network estimation.

Instruments

Demographic characteristics

Demographic and clinical data relevant to the study objectives were collected, including age, sex, marital status, fasting blood glucose, and disease duration.

Measurement of IO

The IO Scale (IOS), developed by Yang et al.23, was employed to measure IO. This unidimensional scale consists of 8 items scored on a five-point scale from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater IO. In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.89.

Measurement of CF

CF was measured using the CFQ, originally developed by Gillanders et al.24 and adapted into Chinese by Zhang et al. The CFQ consists of 9 items scored from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Higher scores indicate greater CF and psychological inflexibility. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.95.

Measurement of HL

The Diabetes HL Scale (DHLS) developed by Zhu et al.25 was used to assess HL. The DHLS consists of three dimensions (functional, interactive, and critical HL) comprising 19 items in total. Each item is scored using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all possible”) to 5 (“completely possible”), with total scores ranging from 19 to 95 points. Higher scores indicate better HL. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93.

Data analysis

Moderated network analysis pertains to the influence of an external variable on the intensity of inter-variable connections within a network. Conversely, mediation network analysis addresses the mechanisms underlying indirect effects through causal pathways26. Given this distinction, our methodology entailed the construction of a moderated network analysis model. The network estimates conditional dependence relationships among variables through a partial correlation graphical model, which inherently controls for all included variables, thus rendering the control for demographic variables unnecessary27. Based on the symptom network approach, all outcome variables (nodes, questionnaire items) were assumed to follow multivariate or univariate normal distributions. Model parameters were jointly estimated using the standardized inverse covariance matrix (partial correlation matrix). The extended Bayesian information criterion (EBIC)28 and graphical least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)29,30 were used to identify the optimal penalty coefficient for shrinkage, resulting in a sparse network model based on inter-node correlations.

The network structure was estimated using the fitNetwork function, which applies nodewise regression, a sequential method employing univariate regression models for structure estimation31. Interactions and their effect coefficients in the moderated network were visualized using the plotCoefs and intsPlot functions. This enabled the identification and interpretation of significant interactions. Network visualizations were generated using the PlotNet function following the “AND” rule, drawing edges only when variables mutually predicted each other with significant regression coefficients. Network stability was assessed using case-dropping bootstrap procedures32. Analysis progressed from micro-level moderated network analysis to macro-level response surface analysis. All analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and R (v4.3.2).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants

The study cohort comprised 233 participants with heterogeneous demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics (in Table 1). The mean age was 38.58 years (SD = 13.74), and males slightly outnumbered females (57.5%). More than half of the participants were married with children (55.4%). In terms of occupation, the majority were farmers (60.5%), followed by retirees (24.9%). Regarding educational attainment, high school education was most common (50.6%), followed by junior high school (19.3%) and a bachelor’s degree or higher (14.6%). The predominant medical payment method was the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (68.7%), followed by self-payment (17.6%). Clinically, nearly half of the patients had a disease duration of less than 6 months (46.4%). The majority presented with chronic diabetic complications (69.5%), and the mean fasting blood glucose level was 6.48 mmol/L (SD = 1.00). The most frequently reported treatment regimen was monotherapy with oral hypoglycemic agents (35.2%).

Network estimation

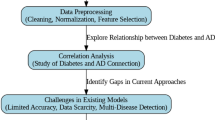

A hierarchical LASSO approach was utilized to select variables and estimate a sparse network, effectively reducing the risk of false positives and minimizing spurious connections. The resulting network structure is illustrated in Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. S1 (Fig. 1). Following this, the nodewise adjacency matrix (Table S2) and the interaction term matrix (Table S3) were computed to facilitate further network analyses involving MNMs. Regression coefficients, including their 95% confidence intervals, for CIO, HL, and CF items, are presented in Fig. 2 (five symptom panels) and Fig. 1 (CI plots). Figure 3 demonstrates the MNMs generated from the nodewise adjacency and interaction term matrices.

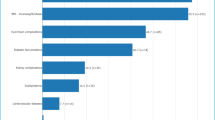

Estimated model coefficients and confidence intervals. (1) The horizontal axis indicates the effect coefficient (β), and the vertical axis lists all potential interactions. Effects are statistically significant when their confidence intervals do not include zero. (2) HL1: functional health literacy, HL2: interactive health literacy, HL3: critical health literacy, IO1: diabetes info overload perception, IO2: excessive diabetes info burden, IO3: multi-channel diabetes info stress, IO4: diabetes info overwhelm, IO5: diabetes info device maintenance increase, IO6: diabetes info checking tendency, IO7: critical diabetes info omission, IO8: diabetes info browsing reduction.

Conditional network models at values of the mean ± SD of CF. (1) Variables are displayed as circle nodes, pairwise interactions are presented as edges between pairs of nodes (circles). (2) The green edges represent positive linear relations, the red edges represent negative linear relations. (3) The widths of edges are proportional to the absolute value of the parameter.

Table S2 indicated significant reciprocal associations between HL and IO. Node regression analyses identified three notably robust relationships: “perceived diabetes information overload” with “functional health literacy”, “multi-channel diabetes info stress” with “interactive health literacy”, and “diabetes info browsing reduction” with “functional health literacy”. Additionally, Table S3 underscored variables forming significant interactions with the moderator (M), specifically social capital, including combinations of “perceived diabetes information overload” with “functional health literacy”, “multi-channel diabetes info stress” with “functional health literacy”, “diabetes info device maintenance increase” with “interactive health literacy”, “functional health literacy” with “multi-channel diabetes info stress”, and “interactive health literacy” with “diabetes info device maintenance increase”. Consistent with expectations, reductions in CF amplified the positive influences of “diabetes info overload perception” and “multi-channel diabetes info stress” on “functional health literacy”, as well as the impact of “diabetes info device maintenance increase” on “interactive health literacy”.

Centrality, stability, and accuracy

Figure S2 illustrated that within the moderated network models (MNMs), “Diabetes info overload perception” displayed the highest measures of betweenness, closeness, and strength. Stability assessments of edge weights and centrality metrics were performed using case-dropping subset bootstrapping, as presented in Fig. 4.

Discussion

This study employs the regulatory network method, innovatively integrating information behavior and psychological factors from both total-score and item-level perspectives. Our findings indicate that CF significantly moderates the relationship between IO and HL in patients with T2DM. Patients exhibiting low CF and low IO levels possess better HL. Moreover, lower CF may partially alleviate the adverse effects of IO on HL.

The moderated network analysis approach was utilized to examine the association between IO and HL levels in T2DM patients. Results confirmed the H1, indicating a significant bidirectional relationship between IO and HL, aligning with previous findings33,34. Specifically, “diabetes info overload perception” and “ diabetes info browsing reduction” were strongly linked with “functional health literacy”. As a fundamental skill for accessing and comprehending health information, functional HL often diminishes due to the depletion of individual cognitive resources caused by massive information35. Individuals with low functional HL struggle to efficiently screen and integrate information, become easily frustrated by complex guidelines or medical terminology, and consequently experience higher perceptions of IO, leading them to actively limit information exposure36. Additionally, the association between “multi-channel diabetes info stress” and “interactive health literacy” was the strongest observed. Unlike other chronic conditions, self-management decisions in T2DM often involve complex scenarios37. For instance, patients may struggle with dietary choices at social gatherings or responses to hypoglycemic episodes. Cognitive load theory38 suggests that exposure to multi-channel information often conveys contradictory or excessive messages, further impairing executive functions and self-regulation, and subsequently reducing an individual’s willingness to engage in health interactions. Therefore, healthcare providers should prioritize enhancing patients’ health information management by delivering streamlined and consolidated health education. This approach mitigates cognitive load from conflicting multi-channel information. For patients with limited functional health literacy, clear and simplified instructions should be provided, coupled with guidance on effective information screening strategies, to alleviate perceptions of information overload and promote proactive health engagement.

The present study also identified cognitive fusion plays a significant moderating role in the relationship between IO and HL, thus supporting H2. This finding indicated that reduced cognitive rigidity could mitigate the negative effects of IO on HL, consistent with previous studies16. Notably, as cognitive integration decreased, the positive effects of “diabetes info overload perception” and “multi-channel diabetes info stress” on “functional health literacy” as well as “diabetes info device maintenance increase” on “interactive health literacy” were significantly enhanced, suggesting that low cognitive fusion attenuates the unfavorable effects of IO. The social cognitive theory20 highlights that individuals’ cognitive functions can mitigate environmental stimuli, which precisely supports the aforementioned research findings. CF causes individuals to automatically extract negative events and conflate them with negative thoughts, self-assessment, and cognition, thereby weakening self-management capabilities39. T2DM patients may exhibit catastrophic thinking or excessive fixation on individual blood sugar values, resulting in rigid cognitive patterns40. Prior research has shown that CF weakens prefrontal-limbic system connections, triggering experiential avoidance, reducing stress resilience, and even leading to social withdrawal41. Furthermore, reduced cognitive load enables patients to focus more effectively on behavioral tasks. Meanwhile, device-maintenance behaviors passively promote interactions with health information by enforcing exposure to healthcare tools, enhancing the practical application of HL. Therefore, Healthcare professionals should attach importance to the assessment and intervention of patients’ cognitive fusion levels, incorporate mindfulness, cognitive defusion and other psychological flexibility training methods into daily health education42, help patients reduce rigid fixation on negative health information, thereby alleviating the negative impact of information overload on health literacy and improving their self-management ability. In conclusion, moving beyond generic health education, a combined focus on environmental simplification and cognitive flexibility training can create a more supportive ecosystem for patients with T2DM.

Limitations

Several limitations exist in this study. First, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships; future research should employ longitudinal designs. Second, this research only included hospitals from Guangdong Province, limiting its generalizability. Future validation should incorporate multicenter studies involving larger populations.

Conclusion

This study constructed a MNM to examine cognitive integration as a buffer against the adverse effects of IO on HL in patients with T2DM. Specifically, it identified positive effects of IO1 and IO3 on HL1, as well as the influence of IO5 on HL2. Additionally, IO1 exhibited the highest centrality index, and the overall model demonstrated robust stability. These results suggest that healthcare providers should target cognitive integration interventions in long-term T2DM management to prevent psychological rigidity and mitigate the negative effects of IO.

Data availability

Data and materials are available to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yan, Y. et al. Prevalence, awareness and control of type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk factors in Chinese elderly population. BMC Public. Health. 22, 1382. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13759-9 (2022).

Murea, M., Ma, L. & Freedman, B. I. Genetic and environmental factors associated with type 2 diabetes and diabetic vascular complications. Rev. Diabet. Stud: RDS. 9, 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1900/RDS.2012.9.6 (2012).

Tb, E. L. & Jw, H. Lifestyle factors, self-management and patient empowerment in diabetes care. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319885455 (2019). 26 2_suppl.

What is health literacy? | health literacy | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/health-literacy/php/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/index.html. Accessed 21 Aug 2025.

Kelly, A., Noctor, E., Ryan, L. & van de Ven, P. The effectiveness of a custom AI chatbot for type 2 diabetes mellitus health literacy: Development and evaluation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 27, e70131. https://doi.org/10.2196/70131 (2025).

Schillinger, D. et al. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA 288, 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.4.475 (2002).

Sen, A. et al. Advancement of artificial intelligence based treatment strategy in type 2 diabetes: A critical update. J. Pharm. Anal. 15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2025.101305 (2025).

Bai, X., Lian, S., Sun, X., Niu, G. & Liu, J. The relationship between information hoarding and selective exposure: The role of information overload, identity bubble reinforcement, and intolerance of uncertainty. BMC Psychol. 13, 736. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03062-8 (2025).

Ramírez, A. S. & Arellano Carmona, K. Beyond fatalism: Information overload as a mechanism to understand health disparities. Soc. Sci. Med. 219, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.006 (2018).

Crook, B., Stephens, K. K., Pastorek, A. E., Mackert, M. & Donovan, E. E. Sharing health information and influencing behavioral intentions: The role of health literacy, information overload, and the internet in the diffusion of healthy heart information. Health Commun. 31, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.936336 (2016).

Nutbeam, D. & Lloyd, J. E. Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public. Health. 42, 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529 (2021).

Khaleel, I. et al. Health information overload among health consumers: A scoping review. Patient Educ. Couns. 103, 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.008 (2020).

Mastin-Purcell, L., Richdale, A. L., Lawson, L. P. & Morris, E. M. J. Associations between psychological inflexibility processes, pre‐sleep arousal and sleep quality. Psychol. Psychother. 98, 606. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12584 (2025).

Cozza, A. et al. Effects of antidiabetic medications on the relationship between type 2 diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairment. Ageing Res. Rev. 112, 102834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2025.102834 (2025).

Chi, H., Song, M., Zhang, J., Zhou, J. & Liu, D. Relationship between acute glucose variability and cognitive decline in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 18, e0289782. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289782 (2023).

Tao, Z., Wang, Z., Lan, Y., Zhang, W. & Qiu, B. Socioeconomic status impacts Chinese late adolescents’ internalizing problems: Risk role of psychological insecurity and cognitive fusion. BMC Public Health. 25, 1427. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22628-0 (2025).

Information need as trigger. And driver of information seeking: A conceptual analysis. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 69, 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-08-2016-0139 (2017).

Meyerhoff, H. S., Grinschgl, S., Papenmeier, F. & Gilbert, S. J. Individual differences in cognitive offloading: A comparison of intention offloading, pattern copy, and short-term memory capacity. Cognit Res: Princ Implic. 6, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00298-x (2021).

Borsboom, D. & Cramer, A. O. J. Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608 (2013).

Ruyang, L. & Hedi, Y. Wellness misinformation on social media: A systematic review using social cognitive theory. Health Commun. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2025.2555614 (2025).

Shi, J-Y. et al. Effect of a group-based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) intervention on self-esteem and psychological flexibility in patients with schizophrenia in remission. Schizophr Res. 255, 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.03.042 (2023).

Papachristou, N. et al. Network analysis of the multidimensional symptom experience of oncology. Sci. Rep. 9, 2258. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36973-1 (2019).

Obamiro, K. & Lee, K. Information overload in patients with atrial fibrillation: Can the cancer information overload (CIO) scale be used? Patient Educ. Couns. 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.005 (2019).

Gillanders, D. T. et al. The development and initial validation of the cognitive fusion questionnaire. Behav. Ther. 45, 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.001 (2014).

朱冬梅 张伟, 尹卫, 刘巧艳. 基于分层模型糖尿病健康素养量表的编制. 镇江高专学报. 65–68.

Ls, E. Jr Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.1 (2007). 12.

Epskamp, S., Rhemtulla, M. & Borsboom, D. Generalized network psychometrics: Combining network and latent variable models. Psychometrika 82, 904–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-017-9557-x (2017).

Haslbeck, J. M. B. & Waldorp, L. J. Mgm: Estimating time-varying mixed graphical models in high-dimensional data. J. Stat. Softw. 93, 1–46. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v093.i08 (2020).

Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical Lasso. Biostatics (Oxf Engl). 9, 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045 (2008).

Bien, J., Taylor, J. & Tibshirani, R. A Lasso for hierarchical interactions. Ann. Stat. 41, 1111–1141. https://doi.org/10.1214/13-AOS1096 (2013).

Epskamp, S., Waldorp, L. J., Mõttus, R. & Borsboom, D. The Gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 53, 453–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1454823 (2018).

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D. & Fried, E. I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods. 50, 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1 (2018).

Zhao, B-Y., Chen, M-R., Lin, R., Yan, Y-J. & Li, H. Influence of information anxiety on core competency of registered nurses: Mediating effect of digital health literacy. BMC Nurs. 23, 626. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02275-3 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Linking online health information seeking to cancer information overload among Chinese cancer patients’ family members. Digit. Health 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076251336308 (2025).

von Wagner, C., Knight, K., Steptoe, A. & Wardle, J. Functional health literacy and health-promoting behaviour in a national sample of British adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 61, 1086–1090. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.053967 (2007).

Chen, S., Bai, Q., Zhu, J. & Liu, G. Impact of functional, communicative, critical and distributed health literacy on self-management behaviors in chronic disease patients across socioeconomic groups. BMC Public. Health. 25, 1776. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23003-9 (2025).

Hs, H. L. Moderating effect of health literacy on the relationship between diabetes self-management education and self-care monitoring activities among individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Public Health 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-23765-2 (2025).

Xiao, F. et al. Neural mechanisms underlying intrinsic and extraneous cognitive loads in numerical inductive reasoning. Psychophysiology 62, e70129. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.70129 (2025).

Chung, H. K. S. et al. The validation, reliability, and measurement invariance of the cognitive fusion questionnaire in Chinese community-dwelling adults. BMC Psychol. 13, 629. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-03011-5 (2025).

Kan, W., Qu, M., Wang, Y., Zhang, X. & Xu, L. A review of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cognitive impairment. Front. Endocrinol. 16, 1624472. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2025.1624472 (2025).

Lee, S. W. et al. The neural correlates of thought-action fusion in healthy adults: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Depress. Anxiety. 36, 732–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22933 (2019).

Levin, M. E., Aller, T. B., Klimczak, K. S., Donahue, M. L. & Knudsen, F. M. Digital acceptance and commitment therapy for adults with chronic health conditions: Results from a waitlist-controlled trial. Behav. Res. Ther. 188, 104729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2025.104729 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who completed the questionnaire in this study. We also thank the editors and blind reviewers for their suggestions and comments on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ziqi Ou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-Review &Editing; Jiahao Wei: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-original draft, Writing - Review & Editing; Yanzhi Guo: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing-Review & Editing; Honglang Jiang: Data curation, Formal analysis; Lishi Chen: Software, Visualization, Writing-Review & Editing; Chunli Huang: Project administration, Supervision, Writing-Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ou, Z., Wei, J., Guo, Y. et al. Information overload, cognitive fusion, and health literacy among individuals with type 2 diabetes: a moderated network analysis. Sci Rep 16, 4203 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34279-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34279-7