Abstract

To identify risk factors for blood transfusion during cesarean section in women with major placenta previa. We conducted a retrospective single-center cohort study of 110 women with major placenta previa who underwent cesarean section at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Karlsruhe Municipal Hospital, between 2014 and 2021. We grouped patients by whether they received a perioperative blood transfusion. Maternal characteristics and clinical factors were compared to identify risk factors. Twenty women (18.2%) required a blood transfusion. No significant differences were observed between groups for maternal age, gestational age at delivery, elective versus urgent cesarean section, antepartum bleeding, use of assisted reproductive technology, or history of curettage. Prior cesarean section was associated with higher odds of perioperative transfusion (OR 4.63, 95% CI 1.65–12.95; Holm-adjusted p = 0.049). Major placenta previa itself is a recognized risk factor for obstetric hemorrhage and transfusion. Our study shows that a history of previous cesarean section is associated with an additional increase in transfusion risk. These findings emphasize the importance of careful preoperative planning and counseling in this high-risk population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major placenta previa is one of the most challenging obstetric conditions and can have devastating consequences for both mother and fetus. It can result in catastrophic hemorrhage that may require cesarean hysterectomy and massive blood transfusion. The prevalence of placenta previa is estimated at 0.4–0.5%, with substantial regional variation worldwide1,2. Its frequency has increased in recent decades, largely paralleling the global rise in cesarean deliveries. In a prospective study spanning 19 years, Kollmann et al. reported a 50% increase in the incidence of placenta previa3.

Placenta previa is defined as the presence of placental tissue covering or reaching the internal cervical os beyond 20 weeks of gestation4. Nearly 90% of low-lying placentas diagnosed in the second trimester resolve before term through the phenomenon of placental “migration” or trophotropism5. Persistent placenta previa at term, however, is strongly associated with severe maternal morbidity.

Previous studies have identified several risk factors for major placenta previa, including advanced maternal age, multiparity, assisted reproductive techniques, previous curettage, and particularly a history of cesarean delivery6,7,8,9. The rising global cesarean rate has therefore been recognized as a major contributor to the increasing incidence of placenta previa10.

Major placenta previa is also strongly associated with life-threatening maternal hemorrhage and the need for blood transfusion. Several studies have attempted to identify risk factors for transfusion among women with placenta previa11,12,13,14. However, many of these studies combined major and minor placenta previa, despite evidence that the risk profile differs significantly between these groups15,16.

To address this gap, our study focused exclusively on women with major placenta previa, defined according to the updated AIUM classification17. We aimed to identify clinical risk factors for perioperative blood transfusion in this high-risk population.

Methods

Patient selection

Most previous studies of hemorrhage in women with placenta previa have included heterogeneous patient populations, often combining minor and major forms according to older classification systems. To provide a more refined assessment, we excluded cases of low-lying and marginal placenta previa, as defined by the updated AIUM criteria6,7. Our analysis focused exclusively on women with major placenta previa in order to evaluate maternal hemorrhage and the need for blood transfusion in a homogeneous cohort.

A total of 110 patients with major placenta previa were eligible for inclusion. According to AIUM (2018) criteria, 94 women (85.5%) had placenta previa totalis (full coverage of the internal cervical os), and 16 (14.5%) had placenta previa partialis (partial coverage of the internal cervical os).

Inclusion criteria were: confirmed diagnosis of major placenta previa (totalis or partialis) by ultrasound after 20 weeks of gestation; cesarean section performed at our institution between 2014 and 2021; and availability of complete medical records. Exclusion criteria were: low-lying placenta or marginal placenta previa; multiple gestation; congenital fetal anomalies; and missing or incomplete data.

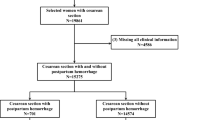

Patient selection is illustrated in Fig. 1, which outlines the stepwise inclusion and exclusion process.

Variables

We focused on maternal characteristics, reproductive history, and antepartum factors relevant to modern obstetric populations in Western Europe. Particular attention was given to advancing maternal age, the increasing use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), a history of curettage, and previous cesarean delivery. We also examined the presence or absence of antepartum bleeding and the timing of cesarean section, recognizing that these nonmodifiable factors must be considered when counseling women with major placenta previa facing life-threatening hemorrhage.

This retrospective cohort study analyzed all women with major placenta previa who underwent cesarean section at Karlsruhe Municipal Hospital between 2014 and 2021. Patients were identified using ICD-10 diagnostic codes O44.00 and O44.01 (placenta previa without bleeding) and O44.10 and O44.11 (placenta previa with bleeding).

According to the updated AIUM classification, we excluded women with low-lying or marginal placenta previa (“minor placenta previa”) and included only those with major placenta previa (totalis and partialis) to achieve a more refined and homogenous assessment. Women were divided into two groups: those who received transfusions of packed red blood cells during cesarean section or before hospital discharge, and those who did not. Preoperative ultrasound findings and full clinical records were reviewed to identify risk factors for transfusion. Specifically, we recorded maternal age, gestational age at delivery, parity, and prior obstetric history (including the number of previous cesarean deliveries).

We also documented key perioperative outcomes such as estimated blood loss, need for cesarean hysterectomy, placenta accreta spectrum involvement, and pre- and postoperative hemoglobin levels. The hemoglobin values were used descriptively to gauge hemorrhage severity and recovery, but were not included as independent variables in the risk factor analysis. The patient selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

This retrospective study used anonymized data and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), which granted a waiver of informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviation, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The primary aim was to identify risk factors for blood transfusion in women with major placenta previa (totalis or partialis). We compared baseline characteristics between the transfusion and no-transfusion groups.

For continuous variables (maternal age, gestational age at cesarean), Student’s t-tests were applied. For categorical variables (elective cesarean, antepartum bleeding, previous caesarean section, ART, previous curettage), chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used, depending on expected frequencies.

P values were corrected for multiple testing using the Bonferroni–Holm method. A corrected p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Effect estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3.0 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2023).

Outcome definition

The primary outcome was the need for perioperative blood transfusion. Transfusion was defined as the administration of at least one unit of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) during the cesarean procedure or before hospital discharge. At our institution, transfusion decisions followed a standardized protocol: transfusion was indicated for hemoglobin < 8 g/dL or in the presence of hemodynamic instability. An institutional massive transfusion protocol (MTP) was available; activation was considered for > 1500 mL blood loss with ongoing bleeding or for rapid blood loss approaching ≥ 2000 mL, even when vital signs were initially stable. Decisions were made in accordance with these institutional guidelines and clinical judgment. Because formal MTP activations were not consistently documented in the retrospective record, activation frequency was not analyzed.

Results

The study included 110 women with major placenta previa, as defined by the updated classification, who underwent cesarean section. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Overall, 20 women required a blood transfusion and 90 did not (transfusion rate 18.2%).

Median estimated blood loss was 1,750 mL (IQR 1,500–3,250) in the transfused group (n = 20) versus 700 mL (IQR 500–1,000) in the non-transfused group (n = 90). The median hemoglobin decrease (ΔHb) was 2.4 g/dL (IQR 1.5–3.5) among transfused patients and 2.3 g/dL (IQR 1.4–2.8) among non-transfused patients (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 2 compares women who required transfusion with those who did not, according to potential risk factors. No significant differences were found for nonmodifiable clinical factors such as maternal age, gestational age at delivery, type of cesarean section (elective or urgent), occurrence of antepartum bleeding, prior curettage, or use of assisted reproductive technology (ART).

A history of previous cesarean section was significantly more common among women who required transfusion (10 of 20; 50%) compared with those who did not (16 of 90; 17.8%). This factor remained significant after adjustment for multiple testing. In absolute terms, perioperative transfusion occurred in 10/26 (38.5%) women with prior cesarean section versus 10/84 (11.9%) without prior cesarean section. The risk ratio was 3.23 (95% CI 1.51–6.90) and the risk difference was + 26.6% points (95% CI + 6.7 to + 46.5). These estimates complement the odds ratio and communicate the clinical magnitude of the association (Supplementary Table S2).

Among women without PAS (n = 100), transfusion occurred in 6/22 (27.3%) with prior cesarean delivery versus 6/78 (7.7%) without (RR 3.55, 95% CI 1.27–9.91). Among those with PAS (n = 10), transfusion occurred in 4/4 (100%) with prior cesarean section versus 4/6 (66.7%) without (RR 1.40, 95% CI 0.75–2.62). A Mantel–Haenszel pooled estimate adjusting for PAS was OR 4.6 (95% CI 1.4–14.8), similar to the crude association. (Supplementary Table S3).

Cesarean hysterectomy was performed in 11 women, 10 of whom had histologically confirmed placenta increta. Eight of these 10 women received transfusions, corresponding to a transfusion rate of 80%, while two did not require blood products. Overall, the transfusion rate was 18.2% (20/110). Among women with prior cesarean, the absolute transfusion risk was 38.5% (10/26), and among those with placenta increta undergoing cesarean hysterectomy, 8/10 (80.0%) required transfusion.

Table 3 provides an overview of additional perioperative outcomes stratified by transfusion status. Of the 110 women, 84 (76.4%) had no prior cesarean deliveries, 19 (17.3%) had one prior cesarean, and 7 (6.4%) had two or more. Consistent with our main finding, a higher proportion of the transfusion group had a history of cesarean delivery. Women who required transfusion also experienced substantially greater blood loss (median estimated blood loss 1.7 L vs. 0.7 L) and were more likely to undergo cesarean hysterectomy compared to those not transfused. Placenta accreta spectrum (typically placenta increta) was present in 40% of transfused patients versus 2% of non-transfused patients. Preoperative hemoglobin levels were slightly lower in the transfusion group, and postoperative hemoglobin was markedly lower in the transfusion group, reflecting the greater hemorrhage and hemodilution despite transfusions (Table 3). Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) was strongly associated with perioperative transfusion: 8/10 (80.0%) with PAS were transfused versus 12/100 (12.0%) without PAS, corresponding to a crude OR 29.3 (95% CI 5.6–154.3).

Discussion

Our study evaluated risk factors for blood transfusion in women with major placenta previa who underwent cesarean section. We observed that a previous cesarean delivery was significantly associated with an increased need for perioperative blood transfusion. This result aligns with earlier studies that reported an elevated hemorrhage risk in women with uterine scarring and abnormal placentation12,13,14,15. Additionally, prior research indicates a dose-dependent increase in hemorrhagic complications with each additional cesarean delivery. In placenta previa cases, multiple previous cesareans confer a progressively higher risk of placenta accreta spectrum and massive hemorrhage18,19. Although our cohort included only seven women with two or more prior cesareans, the trend in transfusion rates supports this escalation of risk.

Other factors such as maternal age, gestational age at delivery, antepartum bleeding, assisted reproductive techniques, and previous curettage showed associations in univariate analysis, but these did not remain significant after correction for multiple testing. This loss of significance may be related to the limited sample size. Our findings are consistent with some previous studies16,17, but differ from others that identified these variables as independent predictors of transfusion18,20.

Placenta increta was present in several cases and contributed to the transfusion burden. Its inclusion in the analysis was clinically justified, but it may also represent a confounder. Because multivariable logistic regression was not feasible due to the small sample size, residual confounding cannot be excluded. The potential influence of abnormal placental invasion on transfusion risk has been highlighted in prior studies19,21,22.

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. The retrospective single-center design carries an inherent risk of selection bias. Data collection was limited to available records, and surgical approaches varied among operators, potentially influencing blood loss and transfusion rates. Differences in surgical management decisions (for example, the threshold for proceeding to cesarean hysterectomy or other hemostatic interventions) could have impacted hemorrhage outcomes independently of patient factors. Moreover, unmeasured variables such as the presence of placenta accreta spectrum in varying degrees could confound the association between prior cesarean and transfusion. Therefore, our ability to draw causal inferences is limited, the observed link between previous cesarean and transfusion may reflect, in part, residual confounding by these factors. While the prior-cesarean association persisted after PAS stratification, precision was limited, particularly in the PAS stratum, and we could not perform stable multivariable adjustment. Additionally, intraoperative blood loss may vary with surgeon experience, surgical technique, and the availability of multidisciplinary support, which we could not fully account for in this retrospective design.

The relatively small sample size restricted the ability to build a multivariable model and may explain why some associations reported by others were not confirmed here14,15,17. Despite these limitations, our analysis focused strictly on cases of major placenta previa according to the updated AIUM classification, thereby improving internal validity by reducing heterogeneity compared with earlier studies that combined major and minor forms10,11.

Clinically, the association between previous cesarean section and transfusion risk emphasizes the importance of careful preoperative planning in women with placenta previa. Major placenta previa itself is a recognized risk factor for massive obstetric hemorrhage and transfusion2,6,8, and our findings highlight that this risk is further increased in women with a history of cesarean delivery. This includes ensuring the availability of adequate blood products, consultation with experienced surgical teams, and comprehensive counseling of patients regarding hemorrhage risk. These considerations are particularly relevant given the rising global rates of cesarean deliveries and the corresponding increase in abnormal placentation2,6,8.

Future research should include larger multicenter prospective studies to validate our findings and to identify additional risk factors. Incorporating multivariable models would allow adjustment for confounding factors, including abnormal placental invasion, and could lead to more accurate prediction of transfusion needs in this high-risk population.

Conclusions

In this exploratory, retrospective cohort of women with major placenta previa, prior cesarean section was associated with an increased risk of perioperative red-cell transfusion. Patients with major placenta previa plus prior cesarean merit enhanced perioperative planning (readily available blood products and an experienced multidisciplinary team).

In women with major placenta previa, the condition itself is a well-established risk factor for significant bleeding and the need for blood transfusion during delivery2,6,8. Our study further demonstrates that a history of previous cesarean section is associated with an additional increased risk of perioperative transfusion. This observation is consistent with earlier research linking uterine scarring to abnormal placentation and hemorrhage12,13,14,15. Other potential risk factors, such as maternal age, gestational week at delivery, antepartum bleeding, previous curettage, and assisted reproductive techniques, did not remain significant after correction for multiple testing.

The findings should be interpreted with caution given the retrospective single-center design, limited sample size, and the absence of multivariable analysis. Placenta increta, while included in the analysis, may have confounded results. These limitations prevent us from drawing firm causal conclusions.

Nevertheless, our results underscore the clinical importance of considering both major placenta previa itself and a history of cesarean delivery when assessing transfusion risk. Women with major placenta previa and a prior cesarean delivery should receive enhanced perioperative planning, including preparation of blood products and management by an experienced multidisciplinary team. For these patients, the availability of blood products, and counseling about hemorrhage risk are essential. Future large-scale prospective studies are required to confirm these associations and to support the development of robust prediction models for transfusion risk.

Data availability

The anonymized dataset generated and analyzed during the current study has been deposited in the Zenodo repository and is publicly available: Baev E, Roth K, Nagel J, Krämer J, Dittrich R, Häberle L, Müller A. Dataset for Risk factors for blood transfusion during cesarean section in women with major placenta previa. Zenodo; 2025. doi:10.5281/zenodo.16933211. A brief STROBE checklist is provided in the Supplement.

References

Cresswell, J. A., Ronsmans, C., Calvert, C. & Filippi, V. Prevalence of placenta Praevia by world region: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 18 (6), 712–724 (2013).

Faiz, A. S. & Ananth, C. V. Etiology and risk factors for placenta previa: an overview and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 13 (3), 175–190 (2003).

Kollmann, M., Gaulhofer, J., Lang, U. & Klaritsch, P. Placenta praevia: incidence, risk factors and outcome. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 29 (9), 1395–1398 (2016).

Anderson-Bagga, F. M. & Sze, A. Placenta Previa. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) (2025).

Oyelese, Y. Placenta previa: the evolving role of ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 34 (2), 123–126 (2009).

Jauniaux, E. et al. Placenta Praevia and placenta accreta: diagnosis and management: Green-top guideline No. 27a. Bjog 126 (1), e1–e48 (2019).

Reddy, U. M., Abuhamad, A. Z., Levine, D. & Saade, G. R. Fetal imaging: executive summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy shriver National Institute of child health and human Development, society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Institute of ultrasound in Medicine, American college of obstetricians and Gynecologists, American college of Radiology, society for pediatric Radiology, and society of radiologists in ultrasound fetal imaging workshop. J. Ultrasound Med. 33 (5), 745–757 (2014).

Thurmond, A. et al. Role of imaging in second and third trimester bleeding. American college of radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria Radiol. 215 Suppl, 895–897 (2000).

Silver, R. M. et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat Cesarean deliveries. Obstet. Gynecol. 107 (6), 1226–1232 (2006).

Downes, K. L., Hinkle, S. N., Sjaarda, L. A., Albert, P. S. & Grantz, K. L. Previous prelabor or intrapartum Cesarean delivery and risk of placenta previa. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 212 (5), 669e1–669e6 (2015).

Ananth, C. V., Smulian, J. C. & Vintzileos, A. M. The association of placenta previa with history of Cesarean delivery and abortion: a metaanalysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 177 (5), 1071–1078 (1997).

Klar, M. & Michels, K. B. Cesarean section and placental disorders in subsequent pregnancies – a meta-analysis. J. Perinat. Med. 42 (5), 571–583 (2014).

Baba, Y. et al. Calculating probability of requiring allogeneic blood transfusion using three preoperative risk factors on Cesarean section for placenta previa. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 291 (2), 281–285 (2015).

Hasegawa, J. et al. Predisposing factors for massive hemorrhage during Cesarean section in patients with placenta previa. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 34 (1), 80–84 (2009).

Boyle, R. K., Waters, B. A. & O’Rourke, P. K. Blood transfusion for caesarean delivery complicated by placenta Praevia. Aust N Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 49 (6), 627–630 (2009).

Titapant, V. & Chongsomboonsuk, T. Associated factors of blood transfusion for caesarean sections in pure placenta Praevia pregnancies. Singap. Med. J. 60 (8), 409–413 (2019).

Oya, A., Nakai, A., Miyake, H., Kawabata, I. & Takeshita, T. Risk factors for peripartum blood transfusion in women with placenta previa: a retrospective analysis. J. Nippon Med. Sch. 75 (3), 146–151 (2008).

Clark, S. L., Koonings, P. P. & Phelan, J. P. Placenta previa/accreta and prior Cesarean section. Obstet. Gynecol. 66 (1), 89–92 (1985).

Gilliam, M., Rosenberg, D. & Davis, F. The likelihood of placenta previa with greater number of Cesarean deliveries and higher parity. Obstet. Gynecol. 99 (6), 976–980 (2002).

Getahun, D., Oyelese, Y., Salihu, H. M. & Ananth, C. V. Previous Cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption. Obstet. Gynecol. 107 (4), 771–778 (2006).

Fox, N. S. et al. 812: risk factors for blood transfusion in patients undergoing high-order Cesarean delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 216 (1), S465 (2017).

Gibbins, K. J., Einerson, B. D., Varner, M. W. & Silver, R. M. Placenta previa and maternal hemorrhagic morbidity. J. Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 31 (4), 494–499 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The present study was performed in fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of ``Dr. med. ``. The research published here has been used for E. Baev`s doctoral thesis in the Medical Faculty of Friedrich Alexander University of Erlangen-Nurrenberg (FAU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EB: data collection, data management, data analysis, manuscript writing, manuscript editing. KR: project development. JN: project development. JK: data management. LH: data analysis. RD: manuscript editing. AM: project development, manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This retrospective study used anonymized data and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), which granted a waiver of informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baev, E., Roth, K., Nagel, J. et al. Risk factors for blood transfusion during cesarean section in women with major placenta previa. Sci Rep 16, 633 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34425-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34425-1