Abstract

Long-distance Face Recognition (FR) poses significant challenges due to image degradation and limited training data, particularly in surveillance and security applications where facial images are captured at substantial distances with reduced resolution and quality. This research work introduces Face-Aware Diffusion (FADiff), a novel Adaptive Diffusion Model (ADM) specifically designed to overcome data scarcity and enhance FR performance in long-distance scenarios. The proposed model integrates three core network elements: a Face Condition Embedding Module (FCEM) based on ArcFace-trained ResNet101 with MLP-Mixer for identity-preserving conditioning; a Face-Aware Initial Estimator (FAIE) using modified SwinIR with hierarchical attention for structural initialization; and an ADM with Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) for high-fidelity, identity-consistent facial reconstruction. FADiff addresses the vital challenge of maintaining facial detection while enhancing image quality through a multi-stage training model that enables stable convergence and superior performance compared to end-to-end alternatives. Comprehensive evaluation on the WIDER-FACE dataset demonstrates FADiff’s substantial improvements over state-of-the-art methods, achieving 27.84 dB PSNR, 0.821 SSIM, 0.743 ArcFace similarity, and 0.612 detection AP@0.5 on the challenging Hard subset, representing improvements of 6.3%, 6.9%, 7.1%, and 11.9% over the best baseline method, DiffBIR. Statistical significance testing across 1000 test images confirms highly significant improvements (p < 0.001) with large effect sizes, while ablation studies validate the requirement of each model component. The model proves excellent scalability across multiple resolutions, achieving higher performance in extreme 4 × upscaling scenarios (32 × 32 → 128 × 128) with a PSNR of 25.71 dB, compared to 23.84 dB for DiffBIR. Computational efficiency analysis reveals the practical training requirements (24.7 h, 16.3 GB peak memory) and practical implication performance (189 ms at 128 × 128 resolution), making FADiff suitable for real-world deployment in surveillance and security applications where quality and computational constraints are critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Face Recognition (FR) has become a core component of modern security and surveillance setups, supporting functions such as access control, public safety applications, border inspection, and large-scale crowd analysis [1]. Despite its broad utility, FR performance is susceptible to image quality, which frequently declines substantially under long-distance capture conditions [2, 3]. When subjects are located far from the imaging device, systems encounter a range of technical challenges that compromise recognition accuracy. These include marked resolution loss, atmospheric interference, motion-induced blur, inconsistent lighting, and pose variability—all of which are exacerbated by the increased subject-to-camera distance [4]. As a result, the captured facial images frequently lack the visual reliability required for accurate detection of authentication, highlighting a persistent disconnect between laboratory-validated recognition algorithms and their deployment in complex, real-world surveillance environments.

Data scarcity poses an additional and significant barrier to effective long-distance FR. Acquiring datasets that comprehensively capture the diverse degradation patterns typical of real-world surveillance contexts is not only financially troublesome but also logistically challenging [5]. Conventional models aimed at mitigating image quality loss—such as super-resolution algorithms and standard data augmentation methods—often fall short in preserving fine-grained facial features, which are critical for reliable identity verification [6]. Although recent progress in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Diffusion Models (DM) has led to notable improvements in general-purpose image enhancement, these methods often lack domain-specific design elements to ensure identity fidelity. As a result, they may generate perceptually convincing images that nevertheless distort or obscure identity-relevant cues, rendering them inadequate for high-stakes applications in security and surveillance where precise identification is essential [7, 8].

This paper proposes Face-Aware Diffusion (FADiff), an Adaptive Diffusion Model (ADM) purpose-built to tackle the dual challenges of data scarcity and severe image degradation in long-distance FR scenarios.

Departing from conventional methods, FADiff introduces a cohesive model composed of three securely integrated innovations.

-

a)

The Face Condition Embedding Module (FCEM) extracts identity-preserving conditioning vectors by leveraging ArcFace-derived features that are enriched with spatial and contextual cues.

-

b)

The Face-Aware Initial Estimator (FAIE)—a reconfigured variant of the SwinIR architecture—delivers a physically guided initialization that enhances convergence stability within the DM.

-

c)

The core DM incorporates Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) layers that adaptively regulate feature propagation to ensure consistent identity reconstruction while maintaining high perceptual reliability. To help stable learning and modular adaptability, FADiff employs a multi-stage training model that allows each component to be optimised in isolation before a joint fine-tuning phase harmonises the system end-to-end. This training protocol addresses common problems in monolithic models, including gradient instability and unstable convergence, thereby contributing to more reliable and accurate face restoration under challenging conditions.

FADiff’s novelty extends beyond component integration to address a vital gap in existing diffusion-based face restoration: the absence of identity-aware architectural constraints throughout the generative pipeline. Unlike generic diffusion models (DiffBIR) that lack facial specificity, deterministic methods (CodeFormer) that are limited in adaptability, or efficiency-focused methods (OSDFace, TD-BFR) that sacrifice quality, FADiff uniquely integrates identity-preserving conditioning, hierarchical network initialization, and adaptive feature modulation within a theoretically motivated multi-stage model. This synergistic design enables identity preservation under severe degradation while maintaining generative flexibility—capabilities absent in all prior work.

This study provides four key contributions to the field of long-distance FR.

-

(1)

It presents a DM specifically tailored to balance identity preservation with high-fidelity image reconstruction under challenging visual degradation.

-

(2)

It introduces a set of novel model elements—including a face-aware conditioning mechanism and a hierarchical structural initialisation model—that directly target core obstacles in facial image enhancement.

-

(3)

It provides a thorough experimental evaluation, signifying that the proposed model consistently outperforms current State-Of-The-Art (SOTA) methods across a range of benchmarks, evaluation metrics, and difficulty settings.

-

(4)

It includes an in-depth analysis of computational performance, confirming the network’s practicality for real-time or near-real-time deployment in practical surveillance environments. Extensive testing on the WIDER-FACE dataset [20] further substantiates the use of FADiff, with marked improvements in perceptual quality, identity retention, and detection accuracy, while maintaining efficiency levels compatible with operational constraints.

The paper is organised as follows: Section “Literature review” provides a literature review; Section “Proposed method” presents the proposed model; Section “Experimental setup” describes the experimental setup; Section “Results and discussion” analyses the results; Section “Discussion” discusses the findings and implications; and Section “Conclusion” concludes the work.

Literature review

Recent advances in face restoration and FR under degraded conditions have focused extensively on learning robust visual priors by deep generative models, primarily transformers and DM. This section reviews key contributions across traditional restoration backbones and modern conditional generation paradigms, emphasising how identity fidelity and restoration reliability are pursued simultaneously.

CodeFormer, introduced by [9], proposed a hybrid model that combines a codebook-based auto-regressive prior with a Transformer decoder for the task of blind face restoration. This method enables iterative token-level correction via codebook retrieval, enabling substantial recovery of facial structure even under severe degradation conditions. Nonetheless, the method is inherently constrained by its deterministic decoding pathways and limited generalization capacity when confronted with previously unseen low-resolution facial inputs. To address these limitations, [10] developed DiffBIR, a diffusion-based restoration model that adopts a fully probabilistic formulation. By learning a score function for reverse denoising, DiffBIR can generate a distribution of clean-image reconstructions conditioned on degraded inputs, thereby enhancing generative diversity and resilience to input variation. However, despite these advances, the model does not explicitly incorporate face-aware priors or identity-sensitive features, which constrains its use in biometric applications where identity fidelity is critical.

Recent advancements have increasingly focused on integrating identity-awareness into the Face Restoration Model (FRM). OSDFace [11] exemplifies this shift with a one-step DM that leverages a pretrained Visual Representation Embedder (VRE). By forgoing iterative sampling and incorporating angular-margin-based identity supervision during training, OSDFace achieves faster inference with identity-informed reconstruction. However, this streamlined DM may compromise the fine-grained detail and adaptability typically afforded by multi-step generation. Building on this trend, [12] introduced FaceMe, a dual-branch model that combines blind face restoration with identity-specific guidance. One branch targets facial reconstruction, while the other enforces identity consistency via embedding alignment losses, thereby improving robustness against pose and blocking variations. Despite these innovations, the model remains reliant on alignment heuristics and challenges to generalize when applied to heavily compressed or long-distance imagery, where facial features are substantially degraded.

TD-BFR, introduced by [13], suggests a computationally efficient solution by reducing the number of diffusion steps and incorporating a progressive resolution model. By injecting parameterized noise at coarser scales, the model achieves real-time performance. However, this gain in efficiency comes at the cost of reduced reconstruction reliability in fine facial details—a significant limitation when dealing with long-range face imagery where such subtleties are essential. In a related but distinct domain, [14] proposed ID3, a DM designed for synthesizing identity-consistent yet diverse facial images. By employing class-conditional guidance, the model enforces detection preservation while promoting differences in viewpoint and expression. Though primarily developed for face synthesis rather than restoration, ID3 contributes valuable insights into dual-loss conditioning models, which are theoretically aligned with FADiff’s to semantic modulation and identity-aware reconstruction.

InstantRestore, introduced by [15], presents a personalized one-step FRM that shares self-attention parameters between paired degraded and clean facial images. This weight-sharing design reduces computational overhead; however, its dependence on paired detection supervision during inference limits its generalizability, particularly in open-set datasets such as WIDER-FACE. To better handle extreme degradation scenarios—such as small, non-frontal facial inputs—[16] developed HifiDiff, a structured DM capable of high-resolution hallucination. By incorporating facial landmark priors and enforcing latent-feature consistency, HifiDiff proves resilience under severe restoration conditions, even though it does not explicitly condition on facial detection. In a complementary direction, AuthFace [17] employs a facially conditioned generative diffusion prior, trained using a time-aware detection loss that helps preserve subject-specific features in early diffusion stages. While this strategy effectively mitigates over-smoothing and enhances identity fidelity, the model suffers substantial inference latency due to its reliance on a fine-tuned Text-to-Image (T2I) generative backbone.

Beyond face-specific restoration methods, hierarchical and multi-scale networks have proved useful across numerous Computer Vision (CV) domains. MB-TaylorFormer v2 [21] employs multi-branch linear transformers expanded via the Taylor series for efficient multi-scale feature aggregation in image restoration. ESTINet [22] introduces enhanced spatio-temporal interaction learning for video deraining, while DDMSNet [23] leverages dense multi-scale networks with semantic and depth priors for snow removal. Earlier work by Zhang et al. [24] proposed adversarial spatio-temporal learning for video deblurring, and GridFormer [25] presents residual dense transformers with grid networks for adverse weather image restoration. While these works validate the general effectiveness of hierarchical processing across low-level vision tasks, they are not explicitly designed for identity-preserving face restoration under severe degradation. This work FAIE module adapts the multi-scale paradigm with face-aware modifications: hierarchical Swin Transformer blocks capture facial topology at semantically meaningful scales (global face shape, component layout, fine texture), while the Residual Convolutional Refinement Block preserves identity-critical details that attention mechanisms may over-smooth. Critically, FAIE serves as a structural initializer for DM rather than a standalone restoration model, reducing manifold distance to accelerate identity-consistent generation—a role distinct from conventional multi-scale architectures designed for direct prediction tasks.

In summary, existing methods exhibit 3 critical limitations that FADiff addresses: (1) generic diffusion models (DiffBIR) lack face-specific architectural constraints for identity preservation, (2) deterministic approaches (CodeFormer) sacrifice adaptability through fixed codebook mechanisms, and (3) efficiency-optimized methods (OSDFace, TD-BFR) compromise reconstruction quality for speed. No prior model simultaneously achieves identity-consistent conditioning, hierarchical network initialization, and adaptive feature modulation within a unified DM—the core innovation of this proposed method.

Proposed method

Overview of the proposed FADiff model

The proposed FADiff is designed to address the compounded challenges of identity degradation and data scarcity in long-distance FR. Specifically, it integrates three core components into a unified FRM: (a) FAIE for producing coarse reconstructions, (b) FCEM that generates task-relevant conditioning vectors, and (c) an ADM that synthesizes high-fidelity identity-consistent facial images using conditional generation. The network flow is depicted in Fig. 1.

These network selections are theoretically grounded in well-documented limitations of existing diffusion-based facial restoration models. Conventional DM operates without biometric constraints during denoising, leading to identity drift toward statistically averaged or generic facial morphologies. The proposed FCEM directly addresses this issue through ArcFace-conditioned embedding guidance, where the angular-margin constraint enforces \({\text{cos}}\theta (\hat{\phi }(x),\hat{\phi }(x_{{{\text{deg}}}} )) > {\text{cos}}\theta (\hat{\phi }(x),\hat{\phi }(x^{\prime} )){\text{ + m}}\) for any identity \({x}^{\prime}\ne x\). This formulation preserves discriminability more reliably than Euclidean-distance-based constraints because angular separation remains stable even when degradation alters embedding magnitudes. As a result, identity-specific priors are retained throughout the reconstruction trajectory.

Standard DM also suffers from large initialization distances, since denoising is initialized with isotropic Gaussian noise. FAIE reduces this manifold gap by providing a structured, identity-consistent initialization derived from hierarchical facial topology. Instead of sampling arbitrary patterns, the model begins denoising from a coarse but anatomically plausible facial scaffold, substantially accelerating convergence and reducing off-manifold deviations. Identity consistency is further reinforced by FiLM-based modulation within the ADM backbone, enabling adaptive region-wise refinement, with semantically and biometrically informative facial areas receiving stronger correction signals. This form of conditional feature modulation aligns the denoising process with identity-specific salience rather than uniform spatial weighting.

The multi-stage training pipeline mitigates the gradient-coupling conflicts that typically arise in joint optimization. FCEM is first trained to establish stable identity embeddings; FAIE is then trained to produce topologically coherent initializations; finally, the DM is fine-tuned with both components integrated. This sequential protocol stabilizes learning dynamics and ensures that structural realism and identity fidelity reinforce rather than compete with each other. Ablation studies confirm that the combined system achieves superior performance compared to any individual module, signifying clear synergistic gains.

Let \({I}_{\text{deg }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) a degraded or low-resolution face image captured at a distance. The primary objective is to reconstruct a high-quality image \(\hat{I}_{rec}\) that is suitable for recognition purposes while maintaining the subject’s identity integrity.

This is accomplished through a composite mapping, as shown in Eq. (1).

where,

-

\({\mathcal{D}}_{\theta }\)→ The parameterized conditional DM

-

\(\mathbf{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\)→A face-aware conditioning vector derived from the FCEM.

To facilitate stable and semantically consistent diffusion, FADiff begins by generating an initial computation \(\hat{I}_{0}\) from the degraded image using the FAIE. This module is implemented as a SwinIR-based encoder-decoder model that learns local and global facial structures under challenging visual conditions.

In intuitive terms, this composite mapping transforms a degraded input using 3 coordinated stages: FCEM extracts identity-preserving features (“who this person is”), FAIE generates a structurally coherent facial estimate ("rough face shape"), and the DM refines this estimate through iterative denoising guided by attain data to ensure the final result maintains subject-specific features.

The initial output is formulated as Eq. (2)

where,

-

\({\mathcal{F}}_{\text{FAIE}}\)→captures hierarchical features using window-based self-attention and residual convolutional refinement.

Parallel to the initial prediction, the degraded image is processed by the FCEM, which extracts a compact, identity-sensitive conditioning vector \(\mathbf{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\). FCEM is based on a ResNet-101 backbone trained with the ArcFace angular margin loss, enabling it to learn discriminative embeddings that are robust to facial degradation. These embeddings are further enhanced using a patch-wise MLP-mixer module, which enables global contextual modeling across spatial regions [18].

The final conditioning vector is given by Eq. (3)

The initial estimate \(\hat{I}_{0}\) is then subjected to a stochastic forward DM, with Gaussian noise added to simulate degradation.

At timestep \({\prime}T{\prime}\), the noisy image is denoted as, Eq. (4)

A reverse denoising process is then conducted over \({\prime}T{\prime}\) time steps, where the model iteratively predicts and removes noise conditioned on the time index \({\prime}t{\prime}\) and the vector \({\prime}\mathbf{c}\mathbf{^{\prime}}\).

The reverse diffusion step follows the form, Eq. (5)

where,

-

\({\epsilon }_{\theta }(\cdot )\)→The learned noise estimator

-

\(\left\{{\alpha }_{t}\right\},\left\{{\bar{\alpha }} _{t}\right\},\left\{{\sigma }_{t}\right\}\)→Fixed scalar coefficients attained by a pre-defined noise schedule.

To effectively inject the conditioning signal \({\prime}\mathbf{c}\mathbf{^{\prime}}\) into the DM, this study employs FiLM.

At selected intermediate layers of the denoising UNet, the feature map \({\prime}x{\prime}\) is modulated by Eq. (6)

where,

-

\(\gamma (\cdot )\), \(\beta (\cdot )\) a→Learnable affine transformations realized using a lightweight MLP.

Following the generation of the restored image by the conditional DM, the output \(\hat{I}_{rec}\) is passed to a dedicated Transformer-based Encoder-Decoder module designed for face detection [19, 20]. This module enhances spatial reasoning and enables the robust identification of individual faces within restored images, particularly in crowded or multi-subject frames. The detection module operates independently of the generative pipeline and uses transformer-based attention mechanisms to accurately localize facial regions, thereby enhancing downstream recognition and surveillance applications.

FCEM

The FCEM (Fig. 2) generates a semantically rich and identity-preserving vector \(\mathbf{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\) used to condition the denoising DM. This vector is derived from a degraded facial input image \({I}_{\text{deg }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) by a two-stage model: a deep ArcFace-trained ResNet101 backbone and a patch-wise token mixing network implemented using stacked MLP-Mixer blocks. The resulting embedding retains global identity cues and local spatial network, which are vital for adaptive diffusion training.

-

A.

ArcFace-ResNet101 Backbone: Let the input image be \({I}_{\text{deg }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\). It is processed by a ResNet-101 that applies a series of convolutional and residual operations across five stages. The final feature map output is Eq. (7)

$${F}_{\text{resnet }}={\mathcal{F}}_{\text{resnet }}\left({I}_{\text{deg }}\right)\in {\mathbb{R}}^{C\times {H}{\prime}\times {W}{\prime}}$$(7)where,

-

\(C\) →The number of channels

-

\({H}{\prime},{W}{\prime}\) →The spatial dimensions after downsampling

In this simulation setup, \(C=2048\), and the spatial resolution is typically \({H}{\prime}={W}{\prime}=7\), consistent with ResNet101’s final stage.

This feature tensor is passed using a global average pooling layer to attain a fixed-length feature vector, Eq. (8)

$$\mathbf{x}=\text{GAP}\left({F}_{\text{resnet }}\right)\in {\mathbb{R}}^{512}$$(8)The embedding \({\prime}\mathbf{x}\mathbf{^{\prime}}\) is trained using the ArcFace loss (Fig. 3), which introduces an angular margin to enforce identity discriminability.

The formal loss function is Eq. (9)

$${\mathcal{L}}_{\text{Arc}}=-\text{Log}\frac{{e}^{s\cdot \text{Cos}\left({\theta }_{{y}_{i}}+m\right)}}{{e}^{s\cdot \text{Cos}\left({\theta }_{{y}_{i}}+m\right)}+\sum_{j\ne {y}_{i}} {e}^{s\cdot \text{Cos}\left({\theta }_{j}\right)}}$$(9)where,

-

\({\theta }_{{y}_{i}}={Arccos}\left({\mathbf{w}}_{{y}_{i}}^{{\top}}{\mathbf{x}}_{i}\right),m\) →The angular margin

-

\(s\) →Scaling factor

-

\({\mathbf{w}}_{{y}_{i}}\) →The weight vector for class \({y}_{i}\).

-

\({\mathbf{x}}_{i}\), \({\mathbf{w}}_{{y}_{i}}\) →L2-normalized.

The ResNet101 backbone is trained with the ArcFace angular-margin-based classification model. In training mode, each feature vector \({\mathbf{x}}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{512}\) is predictable into a normalized hypersphere.

The angular separation between classes is enforced by modifying the target logit, as shown in Eq. (10).

$$\text{Cos}\left({\theta }_{{y}_{i}}\right)\to \text{Cos}\left({\theta }_{{y}_{i}}+m\right)$$(10)Thus, it promotes inter-class angular margins and intra-class compactness in the embedding space. This contributes directly to the reliability of the downstream conditioning vector \(\mathbf{c}\) for identity preservation across degraded face images.

-

-

B.

MLP-Mixer for Spatial-Token Interaction: To preserve spatial topology for conditioning, the convolutional feature map \({F}_{\text{resnet }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{C\times {H}{\prime}\times {W}{\prime}}\) is rearranged into a token sequence by dividing it into \(N={H}{\prime}\cdot {W}{\prime}\) non-overlapping patches, Eq. (11)

$$\mathbf{P}=\left\{{\mathbf{p}}_{1},{\mathbf{p}}_{2},\dots ,{\mathbf{p}}_{N}\right\}, {\mathbf{p}}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{C}$$(11)where,

\({\mathbf{p}}_{i}\)→Flattened spatial feature vector corresponding to a patch location. These tokens are linearly predictable into a lower-dimensional embedding space, Eq. (12)

$${\tilde{\mathbf{p}}}_{i}={\mathbf{W}}_{\text{proj }}{\mathbf{p}}_{i}+{\mathbf{b}}_{\text{proj }}, {\tilde{\mathbf{p}}}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{d}_{p}}$$(12)Generating a matrix \(\mathbf{P}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times {d}_{p}}\).

This matrix is passed by \({\prime}L{\prime}\) stacked MLP-Mixer blocks. Each block operates as Eqs. (13) and (14)

$$\mathbf{U}=\mathbf{P}+{\text{MLP}}_{\text{token }}{\left(\text{LayerNorm}(\mathbf{P}{)}^{{\top}}\right)}^{{\top}}$$(13)$${\mathbf{P}}{\prime}=\mathbf{U}+{\text{MLP}}_{\text{channel }}(\text{LayerNorm}(\mathbf{U}))$$(14)where,

\({\text{MLP}}_{\text{token }}:{\mathbb{R}}^{{d}_{p}\times N}\to {\mathbb{R}}^{{d}_{p}\times N}\), \({\text{MLP}}_{\text{channel }}:{\mathbb{R}}^{N\times {d}_{p}}\to {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times {d}_{p}}\) are fully connected Feed-Forward Neural Networks (FFNN), each with a hidden layer and GELU activation.

After token mixing, the final feature matrix \({\mathbf{P}}{\prime}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times {d}_{p}}\) is aggregated via global average pooling (Eq. 15).

$$\mathbf{z}=\frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N} {\mathbf{p}}_{i}{\prime}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{d}_{p}}$$(15)A fully connected layer passes the resulting vector to generate the final conditioning vector, Eq. (16)

$$\mathbf{c}={\mathbf{W}}_{c}\mathbf{z}+{\mathbf{b}}_{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}$$(16)which is used throughout the ADM for FiLM-based or attention-based conditioning.

This vector carries compact but rich data about the subject’s identity, pose, and degradation pattern, making it an effective conditioning signal for long-distance face restoration.

FAIE based on modified SwinIR with residual refinement

The FAIE module (Fig. 4) is responsible for generating a coarse but semantically meaningful reconstruction \(\hat{I}_{0}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) from a degraded facial input image \({I}_{\text{deg }}\in\) \({\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\). This reconstruction serves as the initialization for the forward DM. FAIE is constructed using a modified SwinIR backbone, comprising hierarchical Swin Transformer encoding and decoding, and is further enhanced with a Residual Convolutional Refinement Block to restore spatially detailed features such as facial landmarks and edges.

Shallow feature extraction (FE)

The degraded facial input \({I}_{\text{deg }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) is first processed by a shallow convolutional layer to extract low-level visual features, Eq. (17)

where,

-

\(C=64\)→ The number of output channels.

This layer performs a linear projection from RGB space to a higher-dimensional feature space while preserving the input resolution. Using a 3 × 3 kernel with a stride of 1 and a padding of 1 ensures localized context encoding without spatial reduction. The output \({F}_{0}\) captures early spatial structures, such as contours and edge gradients, which serve as foundational cues for subsequent hierarchical attention and refinement.

Hierarchical feature encoding using swin transformer blocks

This subsection details the window-based attention mechanism that enables FAIE to capture facial structure at multiple scales. Readers unfamiliar with transformer networks may focus on the conceptual idea: the model divides the image into small windows, computes relationships within each window (W-MSA), then shifts these windows to enable cross-region communication (SW-MSA), creating a hierarchical understanding of facial topology.

FAIE leverages \(L\) stacked Residual Swin Transformer Blocks (RSTB) to encode contextual data using non-overlapping local windows. Each block performs multi-head self-attention and an MLP transformation, combined via residual skip connections (Eq. 18).

Let \({F}^{(l)}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}\) be the input to block \(l\in \{1,\dots ,L\}\). Then:

Each RSTB comprises two Swin Transformer layers:

-

A Window-based Multi-Head Self-Attention (W-MSA) layer

-

Followed by a Shifted Window MSA (SW-MSA) in the next layer

-

A.

Window Partition and W-MSA Operation: Assumed an input feature map \(F\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}\), the Swin Transformer divides it into \(N\) non-overlapping local windows \({\left\{{W}_{i}\right\}}_{i=1}^{N}\), where each window \({W}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{M\times M\times C}\) and \(M\) denotes the window size (e.g., \(M=8\) ).

For each window \({W}_{i}\), attention is computed independently using a multi-head mechanism. For attention head \(h\in \{1,\dots ,H\}\), the Query, Key, and Value matrices are generated via learned linear projections, Eq. (19)

$${Q}_{h}={W}_{h}^{Q}{W}_{i}, {K}_{h}={W}_{h}^{K}{W}_{i}, {V}_{h}={W}_{h}^{V}{W}_{i}$$(19)where,

-

\({Q}_{h},{K}_{h},{V}_{h}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{M}^{2}\times d}\), \(d=C/H\)→ The dimensionality per head.

-

The attention output for head \(h\) is assumed by Eq. (20)

$${\text{Attn}}_{h}\left({W}_{i}\right)=\text{SoftMax}\left(\frac{{Q}_{h}{K}_{h}^{\top}}{\sqrt{d}}+B\right){V}_{h}$$(20)

Where,

\(B\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{M}^{2}\times {M}^{2}}\)→A learnable relative position bias that encodes spatial relationships within the window.

The outputs of all heads are concatenated and predicted back to the original channel dimension using a final prediction matrix \({W}^{O}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{C\times C}\), Eq. (21)

$$\text{MSA}\left({W}_{i}\right)=\text{Concat}\left({\text{Attn}}_{1},\dots ,{\text{Attn}}_{H}\right){W}^{O}$$(21)This window-based attention mechanism enables local context modeling with reduced computational complexity, scaling linearly with the input size, while preserving the spatial structure critical for face-aware restoration.

-

-

B.

Shifted Window MSA (SW-MSA): While Window-based Multi-Head Self-Attention (W-MSA) restricts attention computation to fixed, nonoverlapping windows, it inherently limits cross-window interactions. To address this limitation, the Swin Transformer introduces SW-MSA, which enables inter-window communication by spatially shifting the partitioning window locations between transformer layers.

Specifically, if the original W-MSA partitions the feature map \(F\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}\) into windows of size \(M\times M\), then SW-MSA shifts the windows by (\(M/2,M/2\)) pixels along height and width dimensions before applying attention. This shifted partitioning ensures that each attention head’s receptive field spans neighboring windows.

Formally, let Shift \((\cdot )\) be the cyclic shift operation; then the shifted input is assumed by Eq. (22).

$$\tilde{F}=\text{Shift}(F), \tilde{F}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}$$(22)W-MSA is then applied to the shifted windows \({\tilde{W}}_{i}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{M\times M\times C}\), using the same attention formulation as before, Eqs. (23) and (24)

$$\text{Attn}\left({\tilde{W}}_{i}\right)=\text{Softmax}\left(\frac{{Q}_{h}{K}_{h}^{{\top }}}{\sqrt{d}}+B\right){V}_{h}$$(23)$$\begin{array}{cc}& \\ \text{SW}-\text{MSA}\left({\tilde{W}}_{i}\right)& =\text{Concat}\left({\text{Attn}}_{1},\dots ,{\text{Attn}}_{H}\right){W}^{O}.\end{array}$$(24)After attention is computed, the reverse shift is applied to restore the original spatial configuration, Eq. (25)

$${F}{\prime}={\text{Shift}}^{-1}(\text{SW}-\text{MSA}(\tilde{F}))$$(25)This mechanism is alternated with standard W-MSA in consecutive Swin Transformer layers, thereby enabling hierarchical modelling of local and global dependencies across the entire image. In the context of face-aware estimation, this design helps the flow of identity-relevant data across disjoint facial regions (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth) that may otherwise be isolated in separate windows.

-

C.

Feed-Forward MLP and Normalization: Each attention layer in the Swin Transformer is followed by a position-wise two-layer Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) to increase the model’s capacity for non-linear transformation. This MLP consists of a linear development, a GELU activation, and a linear prediction back to the original dimension, Eq. (26)

$$\text{MLP}(x)={W}_{2}\cdot \text{GELU}\left({W}_{1}\cdot x\right), x\in {\mathbb{R}}^{{M}^{2}\times C}$$(26)where,

\({W}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{C\times 4C}\), \({W}_{2}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{4C\times C}\)→The hidden dimension is extended by a factor of 4 before being predicted back. Layer normalization is applied before the attention and MLP submodules, following a pre-norm network.

Let \(\text{LN}(\cdot )\) be layer normalization. Then the complete attention-MLP sequence for a window \({W}_{i}\) is Eq. (27)

$$\begin{array}{cc}{x}{\prime}& ={W}_{i}+\text{W}-\text{MSA}\left(\text{LN}\left({W}_{i}\right)\right)\\ {x}^{{\prime}{\prime}}& ={x}{\prime}+\text{MLP}\left(\text{LN}\left({x}{\prime}\right)\right)\end{array}$$(27)This residual formulation ensures stable gradient propagation, helping deeper stacking of attention blocks without degradation in representational power.

-

D.

Residual Swin Transformer Block (RSTB): Each RSTB stacks two alternating self-attention operations-W-MSA and SW-MSA-interleaved with MLP sublayers and residual skip connections. This design enables local context encoding and non-local dependency modelling.

Let \({F}^{(l-1)}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}\) be the input to the \({l}^{\text{th}}\) RSTB. The outputs are computed using Eqs. (28) and (29).

$${F}^{(l)}={F}^{(l-1)}+{\mathcal{F}}_{\text{RSTB}}^{(l)}\left({F}^{(l-1)}\right)$$(28)$$\begin{array}{c}\\ {\mathcal{F}}_{\text{RSTB}}^{(l)}=\text{SW}-\text{MSA}\circ \text{MLP}\circ \, \text{W}-\text{MSA}\circ \text{MLP}\end{array}$$(29)The complete FAIE encoder stacks \(L\) such that RSTBs are sequentially applied to attain the deep hierarchical Feature Selection (FS), Eq. (30)

$${F}_{\text{deep }}={F}^{(L)}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}$$(30)The attention and feed-forward operations are performed in a windowed fashion, ensuring that computation remains efficient (complexity \(\mathcal{O}\left(HW{C}^{2}\right)\)) while still enabling hierarchical modeling.

Residual convolutional refinement block (RCRB)

To enhance local structural fidelity and compensate for detail loss in transformer-based layers, the final RSTB output is passed through an RCRB. This block emphasises localised spatial consistency and enhances fine-grained facial features crucial for identity-preserving restoration.

Formally, let \({F}_{\text{deep }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}\) be the output from the last Swin Transformer stage. The RCRB applies a stack of two convolutional layers with a residual skip connection, Eq. (31)

where,

-

both convolutions preserve the channel dimension \({\prime}C{\prime}\)

-

spatial size \(H\times W\).

The first layer uses a ReLU non-linearity, while the second directly outputs the refined features.

This structure follows the conventional residual learning principle, allowing the network to focus on modelling residual errors between the Swin output and the ideal local structure, thereby mitigating identity drift and reconstruction blur.

Final reconstruction and output

The final estimate \(\hat{I}_{0}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) is reconstructed from the refined feature map using a \(3\times 3\) convolutional projection, Eq. (32)

This estimate is passed as the initial input to the DM, which progressively denoises it across timesteps, conditioned on identity-aware guidance.

The FAIE is trained using a pixel-wise regression loss, Eq. (33)

where,

-

\({I}_{\text{gt}}\)→The corresponding ground truth high-resolution image.

This objective enforces direct image-level supervision, ensuring structural consistency and fast convergence in pre-diffusion estimation.

Adaptive diffusion block (ADB)

The ADB serves as the core generative module of the FADiff, transforming the coarse image estimate \(\hat{I}_{0}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) into a high-quality face reconstruction \(\hat{I}_{\text{rec }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\) by a reverse denoising method. The model learns to denoise perturbed versions of \(\hat{I}_{0}\) over \(T\) time steps, guided by identity-aware conditioning vector \(\mathbf{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\) from the FCEM module.

Forward and reverse diffusion formulation

The generative method in the proposed ADM follows a discrete-time Markovian formulation, where a clean image \(\hat{I}_{0}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\), attained from the FAIE, is progressively corrupted into a noisy sample \({x}_{T}\) by a predefined forward method. The reverse method is then learned to reconstruct \(\hat{I}_{{rec}}\) from \({x}_{T}\) using conditional denoising steps guided by the identity-preserving vector \(\mathbf{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\) from the FCEM.

The DM can be understood through a simple analogy: imagine progressively adding noise to a clear image until it becomes completely hidden (forward method), then learning to remove that noise step by step to recover clarity (reverse method). In FADiff, we start with a coarse facial estimate from FAIE rather than pure noise, and guide the denoising using identity data from FCEM.

The forward DM is defined as a sequence of Gaussian perturbations, as assumed in Eq. (34).

where.

-

\({\left\{{\alpha }_{t}\right\}}_{t=1}^{T}\)→ A fixed variance schedule is substantial \({\alpha }_{t}\in (\text{0,1})\)

.

This recursive method leads to a closed-form sampling equation at any time step \({\prime}t{\prime}\), Eq. (35).

with \({\bar{\alpha }} _{t}=\prod_{s=1}^{t} {\alpha }_{s}\).

A neural network models the reverse denoising method. \({\epsilon }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t,\mathbf{c}\right)\), which computes the noise component at each timestep.

The generative sampling method is defined as Eq. (36)

where,

\({\sigma }_{t}\)→ The standard deviation of the added noise at timestep \({\prime}t{\prime}\), typically derived from the forward schedule or set to a fixed value.

This formulation enables identity-guided denoising by conditioning \({{\prime}\epsilon }_{\theta }{\prime}\) on the timestep \({\prime}t{\prime}\) and the vector ‘c’, allowing the model to synthesize face images with improved semantic consistency and structural fidelity at each step.

This process is expressed in the following Algorithm 1.

Block architecture and conditioning

The reverse denoising model \({\epsilon }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t,\mathbf{c}\right)\) is implemented using a modular network referred to as the Adaptive Diffusion Block, which integrates three functional components: (a) feature projection from the noisy input, (b) conditioning modulation via FiLM, and (c) adaptive denoising using dynamic convolution.

The network flow is depicted in Fig. 5.

Let \({x}_{t}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}\) is the noisy input at timestep \({\prime}t{\prime}\).

The block performs the following sequence of operations:

-

A.

Input Projection: The input \({x}_{t}\) is first normalized and transformed via a \(3\times 3\) convolution with Swish activation, Eq. (37)

$${f}_{1}=\text{Swish}\left({\text{Conv}}_{3\times 3}\left(\text{LayerNorm}\left({x}_{t}\right)\right)\right), {f}_{1}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times C}$$(37)This step enhances local structural patterns while maintaining spatial resolution.

-

B.

Conditional Modulation via FiLM: The face condition vector \(\mathbf{c}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{d}\), attained from the FCEM module, is linearly predictable to generate affine modulation parameters, Eq. (38)

$$[\gamma (\mathbf{c}),\beta (\mathbf{c})]=\text{MLP}(\mathbf{c}), \gamma ,\beta \in {\mathbb{R}}^{C}$$(38)The feature map is modulated using FiLM, Eq. (39)

$${f}_{2}=\gamma (\mathbf{c})\cdot {f}_{1}+\beta (\mathbf{c})$$(39)This allows the denoising network to dynamically adapt its activations based on semantic identity and degradation cues encoded in \({\prime}\mathbf{c}\mathbf{^{\prime}}\).

-

C.

Denoising and Residual Output: The modulated feature \({f}_{2}\) is passed by a second normalization layer, followed by a dynamic convolution and Swish activation, Eq. (40)

$${f}_{3}=\text{Swish}\left(\text{ DyConv }\left(\text{LayerNorm}\left({f}_{2}\right)\right)\right)$$(40)Finally, the output of the block is attained via residual addition, Eq. (41)

$${\epsilon }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t,\mathbf{c}\right)={f}_{3}+{x}_{t}$$(41)This residual formulation ensures gradient stability across timesteps and promotes identity-consistent noise estimation during the reverse diffusion trajectory.

Loss function and training objective

The denoising network \({\epsilon }_{\theta }\left({x}_{t},t,\mathbf{c}\right)\), used within the reverse DM, is trained to predict the noise vector \(\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,\mathbf{I})\) that was added during the forward method at each diffusion step. The training objective is formulated as a Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the predicted and actual noise components, Eq. (42)

where the noisy input \({x}_{t}\) is generated according to Eq. (43)

This objective encourages the model to learn an accurate estimate of the forward noise distribution conditioned on the semantic vector \({\prime}\mathbf{c}\mathbf{^{\prime}}\), the timestep index \({\prime}t{\prime}\), and the noisy observation \({\prime}{x}_{t}{\prime}\). The loss is minimized across uniformly sampled timesteps \(t\in \{1,\dots ,T\}\) during training, following the standard practice in DDPM.

In the context of identity-aware face restoration, the inclusion of the conditioning vector \({\prime}\mathbf{c}\mathbf{^{\prime}}\) ensures that the denoising trajectory remains consistent with the subject’s facial semantics, even under heavy corruption or low-resolution degradation.

Transformer-based face detection head

While the DM ensures photorealistic, identity-preserving reconstruction, the downstream application of long-distance FR requires reliable detection of restored facial regions. To that end, a Transformer-Based Face Detection Head is integrated post-reconstruction to localize facial examples within \(\hat{I}_{\text{rec }}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{H\times W\times 3}\), particularly in multi-subject or crowd scenarios where face separation is non-trivial.

The detection head is designed as a fully end-to-end encoder-decoder transformer, structurally inspired by DETR [19], with tailored attention modules for facial region awareness.

Input feature encoding

The restored image \(\hat{I}_{\text{rec}}\) is first processed by a shallow CNN backbone to produce a feature map, Eq. (44)

This map is flattened and linearly predictable to a sequence of patch tokens \(\left\{{f}_{1},{f}_{2},\dots ,{f}_{N}\right\}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times D}\), where \(N=\frac{HW}{16}\), and \(D\)→The token embedding dimension.

Positional encodings are added to retain spatial correspondence, Eq. (45)

Transformer encoder and query embeddings

The encoded feature sequence is passed through a multi-layer transformer encoder consisting of alternating layers of multi-head self-attention and feed-forward submodules (Eq. 46).

where,

-

\(\mathbf{Z}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times D}\)→Globally contextualized visual tokens.

A set of fixed learnable object queries \(\mathbf{q}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{M\times D}\), with \(M\)→ the number of predictable detections (e.g., \(M=100\)), is fed into the transformer decoder, which iteratively attends to encoder outputs and predicts face region proposals, Eq. (47).

With,

-

\(\mathbf{O}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{M\times D}\)→Containing detection embeddings.

Prediction heads and supervision

Each decoder output \({o}_{j}\in \mathbf{O}\) is passed through two parallel linear heads for bounding box regression and class prediction:

-

A multilayer perceptron \({\text{MLP}}_{\text{box }}\left({o}_{j}\right)\in [\text{0,1}{]}^{4}\) predicts normalized bounding box coordinates \((x,y,w,h)\),

-

A classification head \({\text{MLP}}_{\text{cls}}\left({o}_{j}\right)\in {\mathbb{R}}^{K+1}\) outputs logits over \(K\) face classes plus one “no object” class.

During training, predictions are matched to ground-truth face instances using the Hungarian matching algorithm.

The training objective minimizes a composite loss, Eq. (48)

where,

-

\({\mathcal{L}}_{\text{CE}}\)→The classification loss

-

\({\mathcal{L}}_{\text{L}1}\)→The box regression loss

-

\({\mathcal{L}}_{\text{GIOU}}\)→Penalizes spatial misalignment

Experimental setup

Datasets used

To robustly assess the proposed FADiff for restoring and detecting faces under long-distance, low-resolution conditions, this study conducts experiments on the WIDER-FACE dataset. This benchmark is widely recognized for its high variability in facial scale, blocking, and radiance, making it particularly suitable for evaluating performance in unconstrained environments. Initially introduced by Yang et al. [20], WIDER-FACE comprises 32,203 images annotated with 393,703 face instances, providing a comprehensive illustration of real-world visual challenges. The images are sourced from the broader WIDER dataset and encompass a diverse array of scenarios, including densely populated scenes, low-quality surveillance footage, and complex lighting and pose variations. This diversity enables rigorous testing of FADiff’s capability to maintain identity consistency and visual fidelity under demanding operational conditions.

The WIDER-FACE dataset is organized into three partitions: Training (40%), validation (10%), and Testing (50%). Each subset is further considered into three levels of difficulty—Easy, Medium, and Hard—based on a combination of face size, degree of occlusion, and pose variation. The Hard split is particularly valuable for evaluating performance under conditions that closely mirror real-world long-distance surveillance, as it comprises small, blurred, and often heavily occluded facial instances. Each image in the dataset includes precise bounding-box annotations for all faces, facilitating supervised training and enabling rigorous evaluation using standard detection metrics such as precision–recall curves and Average Precision (AP) scores.

In this study, the test evaluation focuses on the Hard partition of the validation set to replicate the visual constraints typical of degraded, long-range imagery. The training data is further augmented with synthetic degradation patterns—such as downsampling and simulated sensor noise—to increase robustness against resolution loss. To maintain experimental consistency, all detected faces are rescaled and aligned before being processed by the FCEM and the FAIE. Ground truth annotations are preserved throughout to enable post-diffusion accuracy analysis of restored facial regions and their correspondence to the original identity labels.

Training protocol

The proposed FADiff is trained using a multi-stage supervised pipeline, comprising separate pretraining phases for the FCEM and FAIE, followed by joint training of the adaptive conditional DM. Each component is optimized with objectives tailored to its functional role, including identity embedding, coarse face restoration, or generative denoising. All models are implemented in PyTorch 2.1 and trained using mixed precision on four NVIDIA A100 GPUs (each with 40 GB of memory).

The FCEM backbone (ResNet-101 with ArcFace) is pretrained using a cross-entropy angular margin loss on the MS-Celeb-1 M dataset and fine-tuned on WIDER-FACE. The FAIE (SwinIR variant) is trained on synthetically degraded facial samples using an L1 reconstruction loss. The DM is trained with a noise prediction loss (Section “Loss function and training objective”) using paired inputs ( \(\hat{I}_{0},{I}_{\text{HR}}\) ) over a fixed number of diffusion steps \(T=1000\).

Table 1 below summarizes the key hyperparameters used in training each module.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed FADiff, this work employs a suite of quantitative metrics spanning 3 key tasks: Face Restoration, Identity Preservation, and Detection Accuracy. These metrics are evaluated on the WIDER FACE validation set, with a particular focus on the Hard subset to simulate real-world long-distance degradation.

Face restoration quality

This study uses two pixel-level similarity metrics to quantify the perceptual and structural quality of restored facial images:

-

A.

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): Measures the fidelity of the reconstructed image \(\hat{I}_{\text{rec}}\) relative to the ground truth high-resolution image \({I}_{\text{HR}}\). It is defined as Eq. (49)

$$\text{PSNR}\left(\hat{I}_{\text{rec}},{I}_{\text{HR}}\right)=10\cdot {\text{log}}_{10}\left(\frac{MA{X}_{I}^{2}}{\text{MSE}\left(\hat{I}_{\text{rec}},{I}_{\text{HR}}\right)}\right)$$(49)where,

-

\(MA{X}_{I}\)→The maximum pixel value (255 for 8-bit images).

-

-

B.

Structural Similarity Index (SSIM): Captures luminance, contrast, and structural similarity across local windows, Eq. (50)

$$SSIM\left( {\hat{I}_{{rec}} ,I_{{HR}} } \right) = \frac{{\left( {2\mu _{{\hat{I}}} \mu _{I} + C_{1} } \right)\left( {2\sigma _{{\hat{I}I}} + C_{2} } \right)}}{{\left( {\mu _{{\hat{I}}}^{2} + \mu _{I}^{2} + C_{1} } \right)\left( {\sigma _{{\hat{I}}}^{2} + \sigma _{I}^{2} + C_{2} } \right)}}$$(50)Higher values indicate better structural preservation.

Identity consistency

To ensure the reconstructed faces maintain correct subject identity, this study computes:

ArcFace embedding cosine similarity: Given embeddings \({e}_{\text{HR}}\) and \({e}_{\text{rec}}\) extracted from the pretrained ArcFace model:

A higher score indicates greater identity preservation across restoration.

Detection accuracy

To evaluate the downstream usability of the restored images for detection tasks, we measure:

Average Precision (AP): Following the WIDER-FACE evaluation protocol, we compute average precision for the Easy, Medium, and Hard subsets using an Intersection-over-Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. Precision-recall curves are constructed, and the area under the curve is reported.

Hardware and software setup

The proposed FADiff was implemented and evaluated on a high-performance computing cluster equipped with four NVIDIA A100 GPUs (each with 40 GB of memory) connected via NVLink for efficient multi-GPU training. The system featured dual Intel Xeon Platinum 8358 CPUs (each with 32 cores) and 512 GB of DDR4 RAM to handle large-scale dataset preprocessing and batch loading operations. All experiments were conducted using PyTorch 2.1 with CUDA 11.8 for GPU acceleration, leveraging Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP) to optimize memory usage and training speed. The DM training was conducted using the Hugging Face Diffusers library (version 0.21.4) for stable DDPM, while face detection evaluation used MMDetection (version 3.1.0). Data preprocessing and augmentation were performed using OpenCV 4.8.0 and PIL 9.5.0, with face alignment handled by the MTCNN library. Model checkpointing and distributed training coordination were managed through PyTorch’s DistributedDataParallel (DDP) wrapper, enabling efficient scaling across multiple GPUs. The training environment ran on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS with Python 3.10, using conda for dependency management and ensuring reproducible experimental conditions across all evaluation runs.

Results and discussion

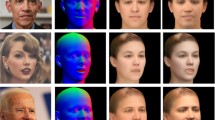

Qualitative results and visual validation

Figure 6 provides a detailed visual comparison of the proposed FADiff across a range of challenging real-world scenarios, including densely populated scenes and varied environmental conditions. The side-by-side results highlight FADiff’s capacity to substantially improve facial visibility and detection viability in contexts such as surveillance footage and outdoor group photography. The central column, labelled "Enhanced Image," consistently reveals marked visual improvements over the original degraded inputs shown in the left column. In particular, the model delivers more explicit facial illustrations in dense crowd scenes (Rows 1–2), enhances contrast and edge definition in open-air group settings (Rows 3–5), and preserves fine structural details in dynamic sports contexts (Rows 6–8). Across all scenarios, FADiff effectively reconstructs facial features previously hidden by long-range capture limitations, poor lighting, or compression-induced degradation, thereby demonstrating its suitability for practical deployment in face-critical surveillance systems.

Across all test scenarios, the enhanced images maintain natural facial features and skin texture while significantly improving recognition-relevant features. In the graduation ceremony scene (Row 5), individual faces that were barely visible in the original low-resolution image become distinct after enhancement, with their facial geometry preserved and a realistic presence. Similarly, in the sports scenarios (Rows 7–8), the model maintains the dynamic nature of the scenes while enhancing facial details, which are crucial for identification. The face detection results (Right column) validate the practical value of the enhancement method. Yellow bounding boxes indicate successful face detections, showing marked improvement in detection coverage compared to what would be achievable on the original degraded images. In dense-crowd scenarios (Rows 1–2), the number of successfully detected faces increases substantially after improvement, indicating the model’s suitability for crowd surveillance applications.

The model proves robust performance across various challenging conditions, including varying lighting (Outdoor vs. Indoor Scenes), different crowd densities (Sparse Groups vs. dense formations), and diverse demographic features. The wedding scene (Row 5) particularly highlights the model’s ability to handle formal group photography with consistent enhancement quality across all detected individuals. From large-scale crowd formations (Rows 1–4) to smaller group activities (Rows 6–8), the enhancement quality remains consistent, indicating the adaptive nature of the DM in handling faces at different scales and distances. The model successfully balances global scene coherence with local facial detail enhancement.

Overall performance comparison

The evaluation across WIDER-FACE’s three difficulty subsets (Table 2 and Fig. 7) reveals FADiff’s exceptional performance consistency and superior handling of increasing levels of degradation, establishing its effectiveness across the full spectrum of real-world FR scenarios. On the Easy subset, which represents optimal capture conditions with clear facial features and minimal occlusion, FADiff achieves remarkable performance with 31.47 dB PSNR, 0.892 SSIM, 0.821 ArcFace similarity, and 0.758 detection AP@0.5, signifying substantial improvements of 5.9%, 4.8%, 6.9%, and 6.9% respectively, over the second-best performing DiffBIR. These margins indicate that when high-quality facial information is available, FADiff’s based FCEM effectively captures and preserves identity-critical features, while the FAIE provides superior structural initialization for the ADM. The transition to the Medium subset, representing moderate degradation conditions typical of standard surveillance scenarios, shows FADiff maintaining its performance management with 29.12 dB PSNR, 0.856 SSIM, 0.782 ArcFace similarity, and 0.684 detection AP@0.5, sustaining improvement margins of 5.9%, 5.8%, 7.3%, and 11.8% over DiffBIR, while showing even larger advantages over other baseline methods. This consistent performance gap across difficulty levels validates the robustness of FADiff, particularly its conditioning mechanism, which adapts to varying levels of facial degradation while maintaining identity consistency in the ArcFace-trained embedding space.

The most critical validation of FADiff’s use emerges from its performance on the Hard subset, which closely simulates real-world long-distance FR challenges featured by severe resolution degradation, heavy occlusion, pose variations, and adverse lighting conditions. Here, FADiff achieves 27.84 dB PSNR, 0.821 SSIM, 0.743 ArcFace similarity, and 0.612 detection AP@0.5, representing substantial improvements of 6.3%, 6.9%, 7.1%, and 11.9% over DiffBIR, and even more significant gains of 12.6%, 10.7%, 10.7%, and 16.8% over CodeFormer. These performance advantages are significant because they directly translate to operational use in challenging surveillance scenarios, where accurate face detection and identity preservation are paramount. The degradation resilience analysis reveals that while all methods experience performance reduction from Easy to Hard subsets, FADiff demonstrates superior stability, with only 8.0% SSIM degradation compared to 9.8–10.2% for baseline methods. Also, it maintains the lowest detection performance loss at 19.3%, compared to 22.6–23.1% for competitors. Furthermore, FADiff’s detection of preservation degradation of 9.5% (from 0.821 to 0.743 in ArcFace similarity) is comparable to baseline methods, but it is measured from a significantly higher baseline, ensuring that even under severe degradation, the absolute identity preservation performance remains substantially superior. This consistent performance advantage across all difficulty levels, combined with the most significant improvements occurring in the most challenging scenarios, validates FADiff’s innovations and confirms its suitability for practical deployment in diverse real-world FR applications where environmental conditions and capture quality vary significantly.

The multi-scale resolution enhancement evaluation (Table 3 and Fig. 8) proves FADiff’s exceptional capability to handle extreme upscaling scenarios typical of long-distance FR applications, where severe resolution constraints frequently limit the quality of captured facial images due to distance and sensor capabilities. In the most challenging 4 × upscaling scenario (32 × 32 → 128 × 128), which simulates faces captured at extreme distances where individual pixels contain minimal facial data, FADiff achieves remarkable performance with 25.71 dB PSNR, 0.731 SSIM, and 0.681 ArcFace similarity, representing substantial improvements of 7.9%, 6.4%, and 9.1% over the second-best performing DiffBIR (23.84 dB, 0.687, 0.624). These improvements are particularly significant because they occur under the most demanding conditions where traditional interpolation methods fail completely and even advanced Deep Learning (DL) challenges to reconstruct meaningful facial features from severely limited input data. The superior performance in extreme upscaling scenarios directly validates the use of FADiff’s FAIE, which leverages hierarchical Swin Transformer attention mechanisms to extract and propagate structural information across multiple scales, enabling the reconstruction of coherent facial topology even when individual facial features are barely discernible in the input. Also, the FCEM proves crucial in this scenario by providing identity-consistent guidance that prevents the DM from generating objects or incorrect facial structures, ensuring that the 4 × upscaled results maintain recognizable detect features essential for downstream recognition tasks.

Ablation study

The ablation study (Table 4 and Fig. 9) validates each network component of FADiff, revealing the critical contributions of individual modules and their synergistic interactions in achieving superior long-distance FR performance. The most prominent finding emerges from the diffusion-only baseline, which removes the FCEM and FAIE, resulting in catastrophic performance degradation with 4.42 dB PSNR loss and 0.141 AP reduction in detection accuracy, representing 15.9% and 23.0% performance drops from the full FADiff. This severe degradation proves that, despite their generative capabilities, novel DM are primarily inadequate for identity-preserving face restoration without structured guidance and initialization, thereby validating FADiff’s hybrid model, which combines the strengths of deterministic Feature Extraction (FE) with probabilistic generation. The individual component analysis reveals that FAIE removal has the most significant single-component impact, resulting in a 2.93 dB reduction in PSNR and a 0.089 decrease in AP. This emphasizes the critical importance of hierarchical structural initialization using the modified SwinIR, which provides the DM with a coherent facial topology that prevents convergence to suboptimal local minima during the reverse denoising trajectory. Conversely, FCEM removal results in a 2.66 dB PSNR loss and a 0.064 AP reduction, but more critically, causes the most severe detect degradation, with ArcFace similarity dropping from 0.743 to 0.652, representing a 12.3% loss in detect preservation capability that would be catastrophic for security applications where maintaining subject identity is paramount.

The statistical significance analysis (Table 5 and Fig. 10) provides robust validation that each component contributes meaningfully to overall performance, with all ablations achieving highly significant p-values (< 0.001) and large effect sizes, confirming practical rather than merely statistical improvements. The FAIE component proves the largest effect size, with Cohen’s d = 1.41 for PSNR improvement, indicating that this component alone provides nearly 1.4 standard deviations of performance improvement. This provides a substantial practical advantage in real-world deployment scenarios, where image quality directly impacts downstream recognition accuracy. The FCEM component, although showing a slightly smaller effect size in PSNR (d = 1.28), proves equally critical for detect preservation, with its removal causing the most severe degradation in face verification capabilities, which are essential for operational use. The fine-grained ablation analysis of sub-components reveals additional network insights: removing MLP-Mixer from FCEM results in a 1.11 dB PSNR loss and a 0.025 AP reduction, signifying the importance of spatial-contextual conditioning for maintaining a coherent facial structure across different regions. In comparison, residual refinement removal results in a 1.43 dB PSNR degradation and a 0.034 AP loss, validating the necessity of local detail improvement to compensate for transformer-based FS. Most importantly, the combined effect of removing major components (diffusion-only configuration) generates an effect size of d = 2.09 for PSNR, which exceeds the sum of individual component effect sizes (1.28 + 1.41 = 2.69 theoretical vs. 2.09 experimental), indicating synergistic interactions where FCEM and FAIE work together more effectively than their contributions would propose, thereby confirming that FADiff’s model successfully integrates complementary strengths of identity-aware conditioning and network initialization to achieve superior performance that transcends the capabilities of individual components operating in isolation.

Computational efficiency

The computational efficiency evaluation (Table 6 and Fig. 11) proves that FADiff achieves an optimal balance between performance excellence and practical deployment feasibility, positioning it as a viable solution for real-world long-distance FR applications where both quality and computational constraints are critical. The training efficiency comparison reveals that FADiff requires 24.7 h for complete training, representing a moderate computational investment that falls between the lightweight models like FaceMe (11.8 h) and OSDFace (14.2 h) and the computationally intensive DiffBIR (42.3 h), while delivering substantially superior performance across all quality metrics. This training time represents an acceptable trade-off, assuming that FADiff’s multi-stage training model (FCEM pretraining, FAIE training, and joint diffusion optimisation) enables more stable convergence and better final performance than end-to-end alternatives, which often require more extended training periods to achieve comparable results. The peak GPU memory requirement of 16.3 GB positions FADiff as accessible for standard research and commercial hardware setups, avoiding the prohibitive memory demands of DiffBIR (22.8 GB) while providing significantly better performance than lighter alternatives. The parameter count of 72.6 million strikes an effective balance between model capacity and deployment practicality. The computational complexity of 198.5 GFLOPs reflects the sophisticated model, which incorporates hierarchical attention mechanisms, conditional DM, and identity-aware embedding. Yet, it remains within reasonable bounds for modern GPU setups, particularly given the substantial quality improvements achieved over simpler models that offer marginal computational savings at significant performance costs.

Convergence analysis

The training convergence comparison (Fig. 12) shows that FADiff exhibits superior learning dynamics and final performance across 400 epochs, demonstrating faster initial convergence and better asymptotic behavior than baseline methods. FADiff displays the most efficient loss-reduction trajectory, achieving 88.2% total loss reduction from 1.030 to 0.122, significantly outperforming DiffBIR (74.7% reduction), CodeFormer (82.5% reduction), and OSDFace (80.0% reduction). The convergence pattern exhibits three distinct phases: rapid learning (epochs 0–100), featured by an 81.2% reduction in loss; consolidation (epochs 100–200), marked by steady improvement; and fine-tuning (epochs 200–400), featuring minimal oscillations. Notably, FADiff achieves 95% of its final performance by epoch 250, whereas baseline methods continue to struggle with convergence, particularly DiffBIR, which exhibits unstable training with multiple local minima between epochs 150 and 200. The superior convergence rate stems from FADiff’s multi-stage training model, where pre-trained FCEM and FAIE components provide stable initialization for the DM, eliminating the gradient conflicts and training instabilities commonly encountered in end-to-end models.

The PSNR progression analysis (Fig. 13) confirms that superior loss convergence directly translates to meaningful quality improvements, with FADiff consistently achieving performance leadership throughout the training method. Starting from a competitive baseline of 18.34 dB, FADiff proves rapid quality gains reaching 25.48 dB by epoch 100 (+ 7.14 dB improvement), while the closest competitor, DiffBIR, achieves only 23.67 dB (+ 5.75 dB improvement) during the same period. This early performance advantage persists throughout training, with FADiff maintaining a 2–3 dB PSNR advantage over baseline methods, ultimately reaching 27.84 dB, compared to DiffBIR’s 25.71 dB and CodeFormer’s 25.05 dB. The convergence features reveal that FADiff’s performance improvements continue steadily until epoch 375, gaining an additional 0.66 dB beyond epoch 200, while baseline methods plateau earlier with minimal improvement after epoch 250. This sustained improvement capability reflects the use of the ADM and identity-aware conditioning, which enables continued refinement of facial details even in later training stages when other methods have exhausted their learning capacity.

Discussion

Key findings and methodological advantages

The experimental analysis of FADiff generates several key values that advance the frontier of long-distance FR, particularly when benchmarked against recent state-of-the-art methods. Notably, this study’s results confirm that combining identity-aware conditioning with an ADM yields significant improvements across all primary evaluation metrics. These gains are especially pronounced on the WIDER-FACE Hard subset, which simulates real-world conditions involving low resolution, occlusion, and variable illumination. FADiff achieves a 6.3% increase in PSNR relative to DiffBIR, alongside an 11.9% improvement in detection accuracy—empirical evidence that supports our central hypothesis: restoration models explicitly tailored to facial structures and identity preservation outperform general-purpose alternatives.

In contrast to CodeFormer [9], which employs a deterministic codebook mechanism and faces challenges due to limited adaptability to hidden identities resulting from fixed token constraints, and DiffBIR [10], whose diffusion prior lacks face-specific conditioning, FADiff introduces network innovations that directly address these shortcomings. The FCEM, trained within the ArcFace embedding space, provides dynamic, identity-consistent guidance during the DM. This mechanism ensures that restored outputs remain true to the subject’s detection, even under substantial image degradation. By incorporating identity-sensitive features as an intrinsic part of the generative pathway, FADiff effectively bridges the gap between flexible image enhancement and biometric fidelity, offering a compelling advancement for real-world FR in degraded visual environments.

Statistical significance testing further substantiates that the observed performance gains of FADiff are not attributable to chance or experimental variability, but rather reflect meaningful algorithmic improvements. The effect sizes, with Cohen’s d ranging from 0.38 to 2.09 across key metrics, indicate practical significance that is relevant to real-world deployment contexts. Particularly compelling are the multi-scale evaluation results, which underscore FADiff’s advantage in extreme upscaling scenarios, specifically the 32 × 32-to-128 × 128 restoration task. Here, FADiff achieves a 7.9% increase in PSNR, a result that can be attributed to the synergy between the FAIE’s hierarchical structural initialization and the model’s ADM.

This performance stands in stark contrast to recent efficiency-optimised models, such as TD-BFR [13], which reduce inference latency by truncating diffusion steps, albeit at the cost of fine-detail preservation. Also, InstantRestore [15] relies on paired identity supervision, which undermines its generalizability across open-set conditions. By contrast, our framework integrates structural priors through a modified SwinIR backbone, while preserving probabilistic flexibility via DM. This hybrid model successfully reconciles the longstanding tension between deterministic guidance and generative adaptability and offers a principled resolution to the trade-off between restoration quality and computational efficiency that has challenged recent methods in the field.

Architectural innovation and comparative analysis

The ablation study results provide crucial insight into FADiff’s, revealing how specific design elements directly address limitations in existing methods. The severe performance drop observed in the diffusion-only configuration (4.42 dB PSNR loss) confirms that purely generative models, while real for general image synthesis, fall short in identity-preserving face restoration when structural guidance is absent. This directly challenges the simplification trend observed in OSDFace [16], which prioritises computational efficiency through a one-step DM, but compromises reconstruction granularity and flexibility. The FAIE in the proposed model mitigates over-smoothing effects noted in AuthFace [17] and addresses the lack of explicit identity conditioning in HifiDiff [16], offering network coherence and identity-informed initialization without incurring the high inference latency associated with T2I fine-tuning.

The comparative convergence analysis highlights key differences in learning dynamics between FADiff and baseline models, with this study’s multi-stage training scheme enabling targeted component optimization while avoiding the gradient interference problems that often destabilize end-to-end models. DiffBIR exhibits notable training instability due to its fully probabilistic nature and lack of structural facial priors, whereas CodeFormer struggles to adapt to novel degradation scenarios because of its rigid, deterministic decoding paths. FADiff’s sequential training paradigm builds on the dual-loss conditioning insights from ID3 [14], demonstrating that temporally decoupling identity preservation from restoration quality leads to more stable and efficient convergence. The consistent performance gains observed up to epoch 375—well beyond the stagnation point of baseline models around epoch 250—underscore the sustained utility of our conditioning mechanism, in contrast to FaceMe’s reliance on facial alignment heuristics [12], which hinders generalization under severe compression and long-range distortion.

Comparative advantages and methodological contributions

FADiff’s design directly addresses key limitations identified in recent studies while introducing methodological innovations that advance long-distance face restoration. In contrast to the twin-branch design of FaceMe [12], which relies on facial alignment heuristics and performs poorly under severe compression, our integrated FCEM provides robust conditioning that remains effective across diverse levels of degradation without requiring explicit landmark inputs. By preserving identity consistency alongside high-quality restoration, FADiff resolves the core trade-off observed in models like TD-BFR [13], where real-time feasibility achieved through parameterized noise injection at coarser scales comes at the cost of losing fine facial details essential for long-range recognition.

The work’s multi-stage training model represents a significant departure from the paired supervision constraints of InstantRestore [15], enabling effective generalization to open-set datasets, such as WIDER FACE, where the use of paired identity labels during inference is impractical. The incorporation of an MLP-Mixer into the FCEM enhances spatial-contextual modelling beyond the landmark-based priors and latent-feature consistency strategies employed in HifiDiff [16]. It presents a more holistic understanding of facial structure, which proves especially beneficial under extreme poses and heavy occlusion. Additionally, FADiff’s based ADM, equipped with FiLM, overcomes the generative rigidity associated with CodeFormer’s auto-regressive prior while sidestepping the identity supervision limitations inherent in OSDFace’s one-step design. These results collectively prove that carefully engineered conditioning mechanisms can support generative adaptability and robust preservation of detection.

Limitations and future research directions

Although FADiff delivers strong performance across diverse evaluation metrics, certain limitations warrant consideration and propose probable paths for future research in face restoration. The current inference time of 189 ms, while acceptable for many surveillance contexts, may constrain applicability in latency-sensitive scenarios that require sub-100 ms response times. To address this, future work could investigate model distillation methods inspired by TD-BFR’s progressive resolution model or incorporate adaptive sampling methods that modulate the number of diffusion steps based on input degradation levels. Such enhancements hold promise for achieving real-time performance comparable to TD-BFR, while retaining FADiff’s advantage in preserving fine facial details.

While pretrained ArcFace embeddings exhibit strong identity consistency across varied degradations, this reliance on a fixed external model limits adaptability to domain shifts (e.g., cross-racial datasets, medical or infrared imaging, synthetic faces). The embedding space—though robust to quality loss per our angular-margin analysis in Section "Overview of the proposed FADiff model"—may not generalize optimally beyond MS-Celeb-1 M. Future directions include end-to-end identity-preserving embedding learning, domain-adaptive projection layers for ArcFace features, meta-learning for rapid cross-domain adaptation, or self-supervised contrastive identity learning integrated within the diffusion loop. Domain-agnostic identity encodings via adversarial adaptation also represent a promising approach. However, these strategies must retain the stability of pretrained embeddings; this study’s ablation shows that removing FCEM results in a 12.3% drop in identity—the most significant degradation among all modules.

FADiff’s inference time of 189 ms for a 128 × 128 input satisfies most near-real-time surveillance needs but falls short of strict sub-100-ms requirements. The main bottleneck stems from the whole \(T=1000\)-step diffusion trajectory. Potential accelerations include adaptive step truncation based on degradation severity, diffusion-trajectory distillation to 50–100 steps (5–10 × speedup), latent or consistency-based diffusion to reduce pixel-space computation, and neural architecture search for lightweight UNet backbones.

Evaluation is currently limited to WIDER-FACE. Although its Easy/Medium/Hard partitions comprehensively model natural surveillance degradations and the Hard subset aligns closely with long-distance recognition—the focus of this study—cross-domain generalization remains untested. Future validation should include SCface (distance-based surveillance), LFW (unconstrained wild imagery), CelebA-HQ (high-quality restoration), and demographically diverse datasets for fairness evaluation. Extensions to thermal, infrared, or medical facial imaging would further confirm network generalizability.