Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is a complex, polygenic, and heterogeneous disease influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. Several genetic polymorphisms, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), have been implicated in BC susceptibility and prognosis across diverse populations. This study aimed to assess the association between genetic variants in the MMP-2, TYMS, and eNOS genes and breast cancer risk in the Jordanian population. A case–control study was conducted involving 300 BC patients and 321 healthy controls. Genotyping was performed using conventional PCR and PCR–RFLP techniques to analyze one SNV in MMP-2 (rs2285053) and two VNTRs in TYMS (rs45445694) and eNOS. The MMP-2 SNV (rs2285053) and TYMS VNTR (rs45445694) showed significant associations with increased BC risk, whereas the eNOS VNTR exhibited no significant correlation. Significant genetic associations were identified under the co-dominant and recessive models, particularly for the T/T and C/T genotypes compared with C/C. No significant relationship was found between these variants and patient survival; however, TYMS mRNA expression was significantly associated with survival probability (p = 0.0185). Overall, these findings suggest that MMP-2 and TYMS variants contribute to breast cancer susceptibility among Jordanians, with TYMS expression serving as a potential prognostic biomarker.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

By the 20th century, cancer had emerged as one of the most devastating and widespread diseases, with nearly one in four individuals projected to develop it at some point in their lives1. It is defined by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells that can arise in various organs throughout the human body. These cells bypass normal growth-regulatory mechanisms and aggressively invade surrounding tissues, depriving neighboring cells of essential nutrients1. In Jordan, cancer ranks as the second leading cause of death, following cardiovascular diseases. With increased exposure to environmental risk factors and the presence of inherited genetic mutations, cancer incidence is expected to rise further, particularly among the aging population2.

Breast cancer (BC) remains the most prevalent malignancy among women worldwide. Despite significant advances in diagnostics and treatment, it continues to pose a formidable challenge, with no definitive cure to date—a dilemma largely rooted in its biological complexity and heterogeneity3.Through large-scale gene expression profiling, researchers have identified five major molecular subtypes: basal-like, luminal A, luminal B, HER2-positive/ER-negative, and normal breast-like. Each subtype carries a unique clinical fingerprint, with markedly different prognoses. Basal-like tumors are often the most aggressive and difficult to treat, whereas luminal A tumors are typically associated with more favorable outcomes4. Breast cancer risk arises from a convergence of factors. Lifestyle and reproductive patterns—such as delayed first pregnancy, early onset of menstruation, and late menopause—contribute significantly. Family history also plays a pivotal role, especially when multiple relatives are affected. However, the most universal factor is aging, which not only increases susceptibility but also raises the likelihood of accumulating genetic mutations over time5.

Family history is a factor that increases the odds of a woman being diagnosed with breast cancer (BC); numerous studies have reported that women with first-degree relatives affected by BC are more likely to develop the disease themselves6. Around 25% of hereditary cases are due to a pathogenic variant in one of the few genes proven to play a causal relationship to BC, including BRCA1, BRCA2, PTEN, TP53, CDH1, and STK11. Patients suspected to have a family history will be screened for polymorphism in these genes and advised on the appropriate treatment modality7. Although heredity in BC is a factor in the onset of malignancy, most cases are believed to be sporadic events. There are two primary classes of genes which, when harboring a mutation, breast carcinoma will develop: cancer-promoting genes, “oncogenes”, and “tumor suppressor genes”. The first class is activated, while the second is inactivated in cancer cells8. Heritable variants are composed of low penetrance genes like CASP8 (around 5%), moderate penetrance genes like CHEK2 (less than 3%), and high penetrance genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2 (approximately 22%)9.

Tandem repeats (TRs) are highly variable DNA elements that contribute substantially to genome diversity and have been shaped by evolution, playing important roles in human-specific traits, particularly in neural function and susceptibility to neurological and psychiatric disorders10. When TR copy numbers vary between individuals, they are termed variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), which make up a notable portion of the human genome and can influence disease risk through repeat length variation, sequence instability, and population-specific distributions10. VNTRs are originally used as genetic markers that are now recognized to influence gene regulation, mRNA function, protein activity, and disease susceptibility, highlighting their important biological and physiological roles11. Despite extensive research on rare and common genetic variants, much of the inherited risk for many diseases remains unexplained. A retrospective study suggested that variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) may account for part of this missing genetic risk, showing that several VNTRs were significantly associated with increased breast cancer risk and earlier age at diagnosis among BRCA1 mutation carriers, supporting a potential modifying role of VNTRs in breast cancer susceptibility12.

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3 or eNOS) is an isoform of the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) family, along with NOS1 and NOS2. It is located on chromosome 7 at locus 7q35–36 and encodes an mRNA of 4,052 nucleotides and a protein of approximately 1,200 amino acids that is responsible for nitric oxide production13. eNOS (NOS3) is a physiological vasodilator that can also provide vaso-protection in various ways. eNOS inhibits platelet aggregation and adherence to the vascular wall after being released into the vascular lumen, thus helping prevent thrombosis. It also hinders the release of platelet-derived growth factors, which stimulates smooth muscle proliferation and the production of its matrix molecules14. Although the 4b/4a VNTR polymorphism has been reported to be associated with a higher risk of hypertension in the Asian population, this variant is also linked to siRNA production. Endothelial cells carrying the 4b allele (5 copies) produce higher amounts of siRNA, resulting in reduced NOS3 expression compared with cells carrying the 4a allele (4 copies)15,16. It was speculated that the action of eNOS through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) might amplify the solidity of tumor cells and enhance their invasiveness and metastatic ability17. The 4b/4a VNTR polymorphism has been shown to be associated with breast cancer occurrence in the Mexican population, suggesting that it may contribute to angiogenesis within tumor tissue, which could ultimately promote tumor cell growth and migration13.

MMP-2, also known as gelatinase A or type IV collagenase, is encoded by a highly polymorphic gene located on chromosome 16 and consists of 13 exons. The resulting protein has a molecular weight of approximately 72 kDa. In addition to its role in degrading collagen and its various types, MMP-2 exerts both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory effects on different tissues. Polymorphisms in this gene may be associated with an increased risk of cancer due to reduced enzymatic activity18. The MMP-2 rs2285053, Genomic location (NC_000016.10–55478465), (g. -735 C > T) mutation has previously been shown to influence MMP-2 transcription by preventing specificity protein (Sp) 1 transcription factor binding19. A meta-analysis study on MMP-2 mutation suggested that it may increase breast cancer susceptibility20.

TYMS is a gene located on chromosome 18 that contains 8 exons and encodes a 74 kDa protein that forms a homodimer. Using 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate (methylene-THF) as a cofactor, thymidylate synthase (TS) catalyzes the reductive methylation of dUMP to dTMP. This activity maintains a stable dTMP (thymidine-5′-monophosphate) pool, which is essential for DNA replication and repair. The enzyme has attracted interest as a potential target for cancer chemotherapy drugs21. Increased TYMS gene expression has been associated with enhanced invasive and metastatic potential of damaged cells. Human thymidylate synthase (TS) undergoes conformational changes to bind and properly orient substrates for the catalysis of dUMP to dTMP. During this process, the active site residues must realign, a phenomenon well documented in prokaryotic TS, leading to domain closure around the substrate and cofactor22. In some cases, TS binds to its mRNA with significant affinity, causing inhibition of its translation23.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have investigated the association between MMP-2, TYMS, and eNOS gene variants and breast cancer (BC) in the Jordanian population of Arab descent. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the genetic susceptibility of these genes to BC by analyzing variable-number tandem repeats (VNTRs) in the eNOS and TYMS genes, as well as a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP rs2285053) in the MMP-2 gene, in both BC patients and healthy control individuals.

Materials and methods

Sample population

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Jordan University of Science and Technology. Additional approval for patient recruitment, including the collection of blood samples and clinical data, was granted by the Human Ethics Committee. Peripheral blood samples (3 mL) were aseptically collected in EDTA-coated tubes from breast cancer patients who were randomly recruited from the Chemotherapy Clinics at King Abdullah University Hospital and King Hussein Medical Center.

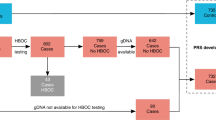

In this case–control study, a total of 300 unrelated Jordanian breast cancer patients were included after excluding individuals who did not meet the inclusion criteria. Eligibility required histopathological confirmation of breast cancer, availability of clinical data in the King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH) registry system, and an age of 28 years or older. Patients undergoing or who had received chemotherapy or radiotherapy were also included. Additionally, blood samples were collected from 321 unrelated, ethnically homogeneous, healthy Jordanian female controls. Both patient and control groups were matched by ethnicity, gender, and age. Clinical, demographic, lifestyle, diagnostic, and treatment-related data were extracted from electronic medical records in accordance with KAUH protocols. Exclusion criteria included individuals unwilling to provide written informed consent, those with incomplete clinical data, and participants related up to the second degree to others enrolled in the study.

Sample analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 621 blood samples using the Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA), which is commercially available. The kit follows the manufacturer’s protocol.

The candidate gene and SNVs selection

In our study, we concentrated on three specific polymorphisms within the candidate genes MMP-2, TYMS, and eNOS, all of which are crucial to breast cancer susceptibility. These polymorphisms were chosen based on their significant functional and biological roles, as well as their location within the selected genes. The selection process utilized public databases, such as the SNV database from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP/) and the Ensemble database (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html), alongside previous literature that underscored the importance of these polymorphisms in various diseases, including breast cancer. Additionally, we examined the functional annotations of the variants studied using HaploReg v4.2 (https://pubs.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php) and RegulomeDB version 2.2 (https://regulomedb.org/regulome-search/).

The results from RegulomeDB revealed that MMP-2 (rs2285053) received a score of 4 with a rating of 0.60906, while TYMS (rs45445694) also scored 4 with a rating of 0.74401. These findings suggest that these polymorphisms are likely to impact binding and may be associated with gene expression regulation. Furthermore, functional annotation via HaploReg v4.2 indicated that rs2285053, located within the intronic region of the MMP-2 gene, is a synonymous coding SNV that could potentially influence promoter and enhancer histone marks and alter transcription factor binding motifs. As a result, these markers might indirectly contribute to breast cancer pathogenesis by modulating the corresponding transcription factors of MMP-2.

DNA genotyping

Genetic polymorphisms in the eNOS, TYMS, and MMP-2 genes were analyzed using classical PCR and PCR-RFLP techniques. The targeted gene regions were first amplified by PCR using specific forward and reverse primers, which are listed in Supplementary Table S113,24,25. For eNOS and TYMS, the amplified products were visualized using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. In the case of MMP-2, PCR amplification was followed by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. The digested PCR products were then separated on a 3% agarose gel, with 8 µL of each sample loaded alongside 7 µL of 50 bp and 100 bp DNA ladders for fragment size estimation. Supplementary Table S2 provides detailed PCR conditions and expected fragment sizes for each gene.

Statistical analysis

The Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) was assessed for all polymorphisms in both breast cancer (BC) patients and control groups using the Chi-square (χ2) goodness-of-fit test, based on the equation (p2 + 2pq + q2 = 1). Allele frequencies and genotype distributions for each polymorphism investigated were compared between the two groups using the Chi-square test. For polymorphisms showing significant associations, four genetic inheritance models—co-dominant, dominant, over-dominant, and recessive—were applied to further analyze genotypic effects.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to assess the impact of MMP-2, eNOS, and TYMS variants on overall survival (OS) in breast cancer patients. Overall survival was defined as the time from diagnosis to death or to the last recorded follow-up for patients who were alive at the time of analysis. Follow-up data were obtained from the Chemotherapy Clinics at King Abdullah University Hospital and King Hussein Medical Center. In addition, mRNA expression data from 1,905 breast cancer patients available in the cBioPortal database26were analyzed to evaluate the association between gene expression levels (high vs. low) and survival outcomes. Survival curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 9 software.

To address multiple testing corrections, the effective number of SNVs was determined using the method described in the previous study27. Furthermore, the Bonferroni correction was applied, setting the significance threshold at α/n, where α is 0.05 and n represents the number of tests28. This correction ensures that the overall p-value remains at a significance level of 0.01667 or less. Through these thorough statistical analyses, our goal was to comprehensively assess the genetic factors linked to disease susceptibility and phenotype expression, while also reducing the likelihood of Type I errors.

Results

Sample characteristics

The Current study consists of 300 unrelated Jordanian Arabs Female BC patients and 321 unrelated healthy Female control individuals. The mean age (± SD) of the patients was (52.32 ± 11.38) years, with a median of 51 and a range of 25–85 years (Supplementary Table S2). A control group of 321 healthy individuals was recruited with an average age of (52.55 ± 11.27), a median of 52, and a range of 23–83 years. Moreover, all of the participants in this study have met the inclusion criteria and agreed to be included in the research. The patient description, including demographic and clinical data and the demographic data for healthy controls, are summarized in Supplementary Table S3 and Table 1.

Allelic and genotypic frequencies of the studied polymorphisms among Jordanians

Table 2 presents the allelic and genotypic frequencies of the SNVs/VNTRs in the TYMS, eNOS, and MMP-2 genes among 621 Jordanians of Arab descent. Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) testing was performed for each variant. The HWE p-values were acceptable for TYMS in cases (p = 0.73) and for eNOS in both controls (p = 0.68) and cases (p = 1.0). In contrast, MMP-2 and TYMS in the control group deviated from HWE, showing significant p-values (p < 0.0001), and were therefore not accepted.

Genetic association between breast cancer patients and healthy individuals

The frequency distribution of the TYMS, eNOS, and MMP-2 and their correlation with breast cancer was studied among both BC patients and control groups in the Jordanian population. Case-control genetic analysis was applied to investigate whether TYMS, eNOS, and MMP-2 are responsible for breast cancer susceptibility. A difference in the genotype and allele frequencies in the BC patients was observed when compared to the healthy individuals in both TYMS and MMP-2, shown in Table 3 and Supplementary Table S4.

Genotype versus phenotype correlation among brest cancer patients

The association between genotypes and clinical phenotypes related to breast cancer (BC) was evaluated to explore potential genotype–phenotype correlations. Pearson’s Chi-square test and one-way ANOVA were employed to assess the statistical significance of these associations. The TYMS genotypes demonstrated significant correlations with several clinical parameters, including breastfeeding status (p = 0.0353), axillary lymph node metastasis (p = 0.0132), lymphovascular invasion (p = 0.0192), and a history of benign breast tumors (p = 0.0171). Similarly, MMP-2 genotypes were significantly associated with age (p = 0.0253), polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (p = 0.0203), and uterine fibroids (p = 0.0256). In contrast, no significant associations were observed between eNOS genotypes and any clinical phenotypes examined. Following Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, the threshold for statistical significance was adjusted to p = 0.01667. After correction, the association between TYMS genotypes and axillary lymph node metastasis remained statistically significant (p = 0.0132). A summary of these findings is presented in Table 4.

Association of MMP-2, eNOS, and TYMS genotypes and the survival rate of BC

All 300 breast cancer (BC) patients were included in the survival analysis, which was conducted using Kaplan–Meier survival curves and the log-rank test. No statistically significant associations were found between the polymorphisms of the three studied genes (MMP-2, TYMS, and eNOS) and overall survival in BC patients. These findings are illustrated in Fig. 1.

Association of MMP-2, eNOS, and TYMS mRNA expression and the survival rate of BC

mRNA expression profiles were collected for 1905 patients diagnosed with BC from the (cBioportal) database21. All the overall status (OS) information has been analyzed; high and low expressions for the three genes (MMP-2, eNOS, and TYMS) were calculated and exported to Graph Pad Prism 9 software to obtain the survival curves and the probability of survival. Only one mRNA expression for the TYMS gene was found to be significant. Log-rank p values were reported as (p = 0.4209), (p = 0.0734) and (p = 0.0185) for MMP-2 ,eNOS, and TYMS respectively as shown in Fig. 2 .

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide and a major cause of cancer-related death. Although improved diagnosis and treatment have reduced mortality, the number of new cases continues to increase, creating a need for better treatments and reliable biomarkers29. Genetic factors play an important role in breast cancer risk. While mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 explain only a small number of familial cases, low-penetrance genetic variants likely account for a larger part of inherited risk. Studying these variants together may improve risk prediction and support targeted prevention strategies30. This study is the first in Jordan to investigate the association between MMP-2, TYMS, and eNOS gene polymorphisms and breast cancer risk. It included 300 breast cancer patients and 321 age- and gender-matched healthy controls.

After testing for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in all examined polymorphisms within both case and control groups, only variants that met HWE criteria were included in the genetic analysis. Two exceptions were noted: the SNV rs2285053 in the MMP-2 gene, which was non-polymorphic, and the VNTR in the TYMS gene within the control group. These variants were therefore excluded from further analysis.

HWE is a fundamental principle in population genetics that describes the expected distribution of alleles and genotypes in a population under ideal conditions, including large population size and random mating, and in the absence of mutation, selection, genetic drift, or gene flow31. When these conditions are met, allele and genotype frequencies are expected to remain stable across generations. Deviations from HWE indicate that one or more of these assumptions may have been violated. In this study, deviations from HWE (p < 0.05) suggest non-random mating as the most likely contributing factor, although other influences such as mutation, selection, or gene flow cannot be excluded32,33. HWE testing is commonly used to evaluate genotype data, as departures from equilibrium may reflect biological or population-specific factors, including purifying selection, copy number variation, inbreeding, or population structure32. Notably, consanguineous marriage is relatively common in Arab populations, including Jordan. A Jordanian study reported that approximately 35% of marriages were consanguineous in 2012, although the prevalence has declined with increased education, urbanization, and greater awareness of the health consequences of such unions34. Consanguinity leads to non-random mating, which reduces genetic diversity and increases the frequency of homozygous genotypes, thereby disrupting HWE assumptions35.

Thymidylate synthase is closely associated with DNA repair and synthesis, and mutations in its gene have been reported to significantly affect patient prognosis. High expression of this enzyme can function as an oncogene, disrupting normal cell regulation and division, thereby promoting cancer development. Increased TYMS gene expression has also been linked to enhanced invasive and metastatic potential of damaged cells. Studies in transgenic mice have demonstrated that overexpression of TYMS results in pancreatic islet hyperplasia and islet cell malignancies36.

Jakobsen et al. reported that TYMS is a polymorphic gene, with mutations that contribute to the development of various malignancies. The most significant mutation is a VNTR located in the promoter region (5′-UTR), which consists of 2 or 3 repeats differing by 28 base pairs37.Another study reported that cells with the 3R/3R genotype had elevated expression of the TYMS gene when compared with the 2R/2R genotype in BC patients25. Another insertion–deletion (indel) mutation within the 3′-UTR has also been associated with multiple diseases. For example, Silva et al. reported that this polymorphism increased the likelihood of cervical abnormalities. Therefore, it may serve as a useful marker for monitoring women with persistent pre-neoplastic cervical lesions38.Furthermore, the TYMS 5’-UTR VNTR and 3’UTR 6-bp indel were strongly related to an elevated risk of non-syndromic cleft lip39. A common variant in the intronic region, involving a C-to-T substitution (rs1059394), has been studied. The TT genotype was strongly associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer40. In studies of brain cancer, one report revealed that the former variant decreased the risk of glioma, whereas the rs2847153 G > A mutation increased susceptibility41.

In our study, the 2R/3R genotype was the most prevalent among Jordanian women, representing 69% of the control group and 50% of breast cancer patients—a difference that was highly significant (p < 0.00001). This pattern closely aligns with findings from Fujishima et al., who reported a similar predominance of the heterozygous 2R/3R genotype (74%) in a Japanese cohort42. Similarly, in Brazil, the heterozygous 2R/3R genotype was the most common, observed in 37% of the population, with the 3R allele being the most frequent at 54%, mirroring our results43.likewise, a Sicilian study documented a 51% incidence of the 2R/3R genotype in their population44.An Argentinean investigation also echoed these trends, with heterozygous genotypes accounting for 52.3% of individuals studied45.However, a recent American study offered a contrasting view, identifying the 2R/2R genotype—not 2R/3R—as the most frequent, accounting for 24.6% of their patients46.

In our study, the most common eNOS genotype was 5R/5R, observed in 71% of the control group and 29% of breast cancer cases, with the 5R allele being the most frequent at 84%. This finding is consistent with research from the South Indian population, where 5R/5R was also the predominant genotype (48.1%), accompanied by a 5R allele frequency of 69%47. Similarly, a study involving the Turkish population reported the homozygous 5R/5R genotype as the most frequent, accounting for 77.3% of individuals48. However, results from Southern Turkey presented a contrasting pattern, identifying the 4R/5R genotype as the most common at 35.3%49. In line with our findings, research on the Mexican population showed 5R/5R as the leading genotype, present in 77% of cases and 87% of controls13.

In the current study, the most frequent genotype was CC in the BC group and TT in the control group, observed in 48% and 47%, respectively. The CC genotype is thought to be associated with increased susceptibility to BC. However, a Tunisian study by Habel et al. contradicted our findings, reporting that the SNV rs2285053 (− 735 C/T) was negatively associated with BC50. A study in the Iranian population found the CC genotype to be more frequent than the other genotypes in both BC cases and controls (59.3% and 71%, respectively). The study reported that the presence of the C allele of MMP-2 increased the risk of BC by 1.64-fold51. A study in the Chinese population by Beeghly-Fadiel et al. found a marginally significant increase in BC risk associated with the heterozygous genotype compared to the homozygous genotype, which did not confer a substantial risk of the disease52. A study reported an association between the rs12285053 C/T polymorphism and reduced susceptibility to digestive cancers, including gastric and lung cancer. The study suggested that populations such as Caucasians and East Asians are more likely to exhibit a significant correlation between the prevalence of this SNV and increased susceptibility to gastric and lung cancer53. Another study had similar findings, confirming an association between MMP-2 (rs2285053) variants and susceptibility to gallbladder cancer (GBC)54.

After analyzing the genotypes of the targeted genes and their polymorphisms alongside the clinical and phenotypic outcomes in breast cancer, significant associations were found between TYMS genotypes and breastfeeding status (p = 0.0353), as well as with axillary lymph node metastasis (p = 0.0132) and lymph vascular invasion (p = 0.0192). These findings align with a Chinese study that reported TYMS polymorphisms to be significantly linked with lymph node metastasis and suggested their potential use as predictive markers in colorectal cancer patients55. Supporting this, another Chinese study found a similar association between TYMS polymorphisms and lymph node metastasis in low-grade glioma56. Additionally, MMP-2 genotypes showed significant correlations with age (p = 0.0253), polycystic ovary syndrome (p = 0.0203), and uterine fibroids (p = 0.0256). This echoes recent research from the Chinese population reporting significant associations between MMP-2 polymorphisms and polycystic ovary syndrome57. Conversely, eNOS genotypes in our study did not display any significant associations with clinical phenotypes, although a study from the Mexican population reported a possible link between eNOS and tumor progression and metastasis13.

In the genetic model analysis, significant associations were observed within the co-dominant model (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.67–1.65, P < 0.0001). This model reflects how each allele of a genetic variant independently contributes to the phenotype or disease risk, with heterozygous individuals typically displaying an intermediate effect compared to either homozygous genotype. Conversely, in the recessive genetic model, no significant associations were found when comparing homozygous T/T and heterozygous C/T genotypes against the common homozygous C/C genotype (OR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.36–0.70, P < 0.0001). This suggests that possessing two copies of the T allele may be necessary to increase breast cancer risk in the Jordanian population.

Our study revealed that the three genes and their polymorphisms were not significantly associated with improved overall survival (OS) in breast cancer patients. However, Kaplan–Meier analysis indicated that patients with higher TYMS expression experienced better OS, with a log-rank p-value of 0.0185. In contrast, previous research has associated positive MMP-2 expression with poorer survival outcomes in breast carcinoma58. Another study highlighted that both MMP-2 and MMP-9 are highly expressed in breast cancer tissues, contributing to lymph node metastasis and thus correlating with poor prognosis; conversely, lower expression levels were associated with better patient outcomes59. Beyond breast cancer, TYMS expression has also been associated with survival outcomes in other cancers; it is closely linked to both overall and disease-free survival in patients with malignant low-grade gliomas56. and in prostate cancer, high TYMS expression has been identified as a strong, independent prognostic marker predictive of overall survival60.

To deepen our understanding of how genetic polymorphisms influence breast cancer susceptibility and treatment efficacy, future research should also consider patients’ lifestyles and habits. This is crucial, as lifestyle factors can interact with genetic profiles, potentially affecting treatment responses and disease progression. Integrating genetic data with lifestyle information brings us closer to truly personalized medicine in breast cancer care.

This study contributes to this evolving field by highlighting the genetic factors that influence breast cancer risk and treatment outcomes in Jordanian patients. By focusing on the unique genetic landscape of this population, our findings aim to lay the foundation for more precise, targeted therapies. Adopting an integrated approach that combines genetics with lifestyle insights promises to enhance our understanding of breast cancer and improve personalized treatment strategies in oncology.

Conclusion

Our study is pioneering in its focus on Jordanian Arab descendants, exploring the impact of specific genetic polymorphisms and ethnicity on breast cancer risk. It provides evidence that genetic variants in MMP-2 and TYMS contribute to breast cancer development in this population and are significantly associated with susceptibility, while higher TYMS expression may be linked to improved overall survival. This research is significant because it addresses the role of genetic factors in an understudied ethnic group, contributing to the advancement of personalized medicine for breast cancer. By expanding scientific inquiry into diverse populations, our work underscores the importance of understanding disease risk factors across different ethnicities. Through genetic association studies in various populations, we aim to validate our findings and reveal the broader implications of genetic influences on breast cancer susceptibility. Overall, this study not only enhances our understanding of breast cancer in the Jordanian context but also provides a foundation for broader insights into its genetic underpinnings across populations.

Limitations

Despite the insights provided by this study, few limitations should be acknowledged. First, the participants sample size, while sufficient for initial analysis, may limit the statistical power to detect associations with less common genotypes or subtle effects, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the lack of duplicate genotyping analysis represents another limitation that should be addressed in subsequent research.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Roy, P. S. & Saikia, B. J. Cancer and cure: A critical analysis. Indian J. Cancer. 53 (3), 441–442. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509X.200658 (2016).

Abdel-Razeq, H., Attiga, F. & Mansour, A. Cancer care in Jordan. Hematol. Oncol. Stem Cell. Ther. 8 (2), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hemonc.2015.02.001 (2015).

Anastasiadi, Z. et al. Breast cancer in young women: an overview. Updates Surg. 69 (3), 313–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-017-0424-1 (2017).

Polyak, K. Breast cancer: origins and evolution. J. Clin. Invest. 117 (11), 3155–3163. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI33295 (2007).

Sun, Y. S. et al. Risk factors and preventions of breast cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 13 (11), 1387–1397 (2017).

Thompson, D. & Easton, D. The genetic epidemiology of breast cancer genes. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 9 (3), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOMG.0000048770.90334.3b (2004).

Shiovitz, S. & Korde, L. A. Genetics of breast cancer: a topic in evolution. Ann. Oncol. 26 (7), 1291–1299. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv022 (2015). Epub 2015 Jan 20.

Liew, M. et al. Closed-tube SNP genotyping without labeled probes/a comparison between unlabeled probe and amplicon melting. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 127 (3), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1309/N7RARXH3623AVKDV (2007).

Ellsworth, R. E. et al. Breast cancer in the personal genomics era. Curr. Genom.. 11 (3), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920210791110951 (2010).

Marshall, J. N. et al. Variable number tandem repeats - Their emerging role in sickness and health. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 246 (12), 1368–1376 (2021).

Nakamura, Y., Koyama, K. & Matsushima, M. VNTR (variable number of tandem repeat) sequences as transcriptional, translational, or functional regulators. J. Hum. Genet. 43 (3), 149–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s100380050059 (1998).

Ding, Y. C. et al. Variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs) as modifiers of breast cancer risk in carriers of BRCA1 185delAG. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 31 (2), 216–222 (2023).

Ramirez-Patino, R. et al. Intron 4 VNTR (4a/b) polymorphism of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with breast cancer in Mexican women. J. Korean Med. Sci. 28 (11), 1587–1594 (2013).

Li, H. & Förstermann, U. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. J. Pathol. 190 (3), 244–254 (2000).

Uwabo, J. et al. Association of a variable number of tandem repeats in the endothelial constitutive nitric oxide synthase gene with essential hypertension in Japanese. Am. J. Hypertens. 11 (1 Pt 1), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00419-6 (1998).

Hyndman, M. E. et al. The T-786–>C mutation in endothelial nitric oxide synthase is associated with hypertension. Hypertension 39 (4), 919–922 (2002).

Xu, W. et al. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell. Res. 12 (5–6), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cr.7290133 (2002).

Tacheva, T. et al. Frequency of the common promoter polymorphism MMP2 -1306 C > T in a population from central Bulgaria. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 29 (2), 351–356 (2015).

Price, S. J., Greaves, D. R. & Watkins, H. Identification of novel, functional genetic variants in the human matrix metalloproteinase-2 gene: role of Sp1 in allele-specific transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 276 (10), 7549–7558 (2001).

Zhou, P. et al. Current evidence on the relationship between four polymorphisms in the matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) gene and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 127 (3), 813–818 (2011).

Sharp, L. & Little, J. Polymorphisms in genes involved in folate metabolism and colorectal neoplasia: a huge review. Am. J. Epidemiol. 159 (5), 423–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh066 (2004).

Schiffer, C. A. et al. Crystal structure of human thymidylate synthase: a structural mechanism for guiding substrates into the active site. Biochemistry 34 (50), 16279–16287. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi00050a007 (1995).

Chu, E. & Allegra, C. J. The role of thymidylate synthase in cellular regulation. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 36, 143–163 (1996).

Liu, J. W. & Chen, D. Q. Correlations of MMP-2 and MMP-9 gene polymorphisms with the risk of hepatopulmonary syndrome in cirrhotic patients: A case-control study. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 34 (11), 634–642 (2018). Epub 2018 Jul 25.

Henríquez, H. Gene polymorphisms in TYMS, MTHFR, p53 and MDR1 as risk factors for breast cancer: A case-control study. Oncol. Rep., 22(06). (2009).

cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics. (n.d.). https://www.cbioportal.org/. (2023).

Nyholt, D. R. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74 (4), 765–769. https://doi.org/10.1086/383251 (2004). Epub 2004 Mar 2.

Li, J. & Ji, L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb). 95 (3), 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717 (2005).

Smolarz, B., Nowak, A. Z. & Romanowicz, H. Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Classification, pathogenesis and treatment (Review of Literature). Cancers (Basel). 14 (10), 2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14102569 (2022).

Zavala, V. A. et al. Genetic epidemiology of breast cancer in Latin America. Genes (Basel), 10(2). (2019).

Edwards, A. W. F. Hardy (1908) and Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Genetics 179 (3), 1143–1150. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.104.92940 (2008).

Chen, B., Cole, J. W. & Grond-Ginsbach, C. Departure from Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium and Genotyping Error. Front Genet, 8, 167. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2017.00167. (2017).

Sunyaev, S. et al. Impact of selection, mutation rate and genetic drift on human genetic variation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 (24), 3325–3330. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddg359 (2003).

Islam, M., Ababneh, F. M. & Khan, M. H. R. Consanguineous marriage in jordan: an updatem J. Biosoc. sci., 50(4):573–578. (2018).

Abramovs, N., Brass, A. & Tassabehji, M. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium in the Large Scale Genomic Sequencing Era. Front Genet., 11:210. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.00210. (2020).

Chen, M. et al. Transgenic expression of human thymidylate synthase accelerates the development of hyperplasia and tumors in the endocrine pancreas. Oncogene 26 (33), 4817–4824 (2007).

Jakobsen, A. et al. Thymidylate synthase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism in normal tissue as predictors of fluorouracil sensitivity. J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (7), 1365–1369 (2005).

Silva, N. N. T. et al. 3’UTR polymorphism of thymidylate synthase gene increased the risk of persistence of pre-neoplastic cervical lesions. BMC Cancer. 20 (1), 323 (2020).

Murthy, J., Venkatesh Babu, G. & Bhaskar, L. V. TYMS gene 5’- and 3’-untranslated region polymorphisms and risk of non-syndromic cleft lip and palate in an Indian population. J. Biomed. Res. 29 (4), 337–339 (2015).

Shen, R. et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the MicroRNA binding-sites of the thymidylate synthase gene predict risk and survival in gastric cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 54 (9), 880–888 (2015).

Yao, L. et al. Association between genetic polymorphisms in TYMS and glioma risk in Chinese patients: A Case-Control study. Onco Targets Ther. 12, p8241–8247 (2019).

Fujishima, M. et al. Relationship between thymidylate synthase (TYMS) gene polymorphism and TYMS protein levels in patients with high-risk breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 30 (10), 4373–4379 (2010).

Jr, J. S. N., Marson, F. A. L. & Bertuzzo, C. S. Thymidylate synthase gene (TYMS) polymorphisms in sporadic and hereditary breast cancer. BMC Res. Notes. 5, 676. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-676 (2012).

Vitello, S. et al. Correlation between polymorphism of TYMS gene and toxicity response to treatment with 5-fluoruracil and capecitabine. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 30 (3), 8970 (2020).

Vazquez, C. et al. Prevalence of thymidylate synthase gene 5’-untranslated region variants in an Argentinean sample. Genet. Mol. Res., 16(1). (2017).

Khushman, M. et al. The prevalence and clinical relevance of 2R/2R TYMS genotype in patients with Gastrointestinal malignancies treated with fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy regimens. Pharmacogenomics J. 21 (3), 308–317 (2021).

Munshi, A. et al. VNTR polymorphism in intron 4 of the eNOS gene and the risk of ischemic stroke in a South Indian population. Brain Res. Bull. 82 (5–6), 247–250 (2010).

DÜZenlİ, M. A. et al. Investigation of eNOS Gene Intron 4 A/B VNTR and Intron 23 Polymorphisms in Patients with Essential Hypertension (Turkish Journal of Medical Sciences, 2010).

Matyar, S. et al. eNOS gene intron 4 a/b VNTR polymorphism is a risk factor for coronary artery disease in Southern Turkey. Clin. Chim. Acta. 354 (1–2), 153–158 (2005).

Habel, A. F. et al. Common matrix metalloproteinase-2 gene variants and altered susceptibility to breast cancer and associated features in Tunisian women. Tumour Biol. 41 (4), (2019).

Yari, K. et al. The MMP-2 -735 C allele is a risk factor for susceptibility to breast cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 15 (15), 6199–6203 (2014).

Beeghly-Fadiel, A. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 polymorphisms and breast cancer susceptibility. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18 (6), 1770–1776 (2009).

L, G. & Shi, Z. L. Z. L, and X MMP2 gene polymorphism and tumor susceptibility study,. Europe PMC, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2568821/v1. (2023).

Sharma, K. L. et al. Higher risk of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2, 7, 9) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP-2) genetic variants to gallbladder cancer. Liver Int. 32 (8), 1278–1286 (2012).

Lu, Y. et al. TYMS serves as a prognostic indicator to predict the lymph node metastasis in Chinese patients with colorectal cancer. Clin. Biochem. 46 (15), 1478–1483 (2013).

Ding, B. et al. Expression of TYMS in lymph node metastasis from low-grade glioma. Oncol. Lett. 10 (3), 1569–1574 (2015).

Li, J. et al. Two MMP2 gene polymorphisms significantly associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: A case-control analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 271, 204–209 (2022).

Talvensaari-Mattila, A., Paakko, P. & Turpeenniemi-Hujanen, T. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) is associated with survival in breast carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 89 (7), 1270–1275 (2003).

Li, H. et al. The relationship between MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression levels with breast cancer incidence and prognosis. Oncol. Lett. 14 (5), 5865–5870 (2017).

Burdelski, C. et al. Overexpression of thymidylate synthase (TYMS) is associated with aggressive tumor features and early PSA recurrence in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 6, 10 (2015).

Funding

The Deanship of Research at the Jordan University of Science and Technology funded the study under grant number RN: 20210403.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.A.-E. designed the study. L.A.-E. and M.A. collected the data and supervised this study. L.A.-E., M.A., H.A. and M.G. conducted the experimental work. All authors analyzed the data and interpreted the results. L.A.-E., M.A., and H.A. wrote the original draft. All authors reviewed the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board of KAUH, Jordan, approved the study. All the clinical investigations were conducted according to the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki (Date: 8 September 2021, No: 9/143/2021).

Consent to participate

All the control subjects were voluntarily involved, and a written informed consent form was signed.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alorjani, M., AL-Eitan, L., Ali, H. et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in breast cancer susceptibility: evaluating MMP-2, TYMS, and eNOS variants in the Jordanian population. Sci Rep 16, 4391 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34531-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34531-0