Abstract

The nasal cavity plays a critical role in respiration and olfaction, functions supported by its turbinate architecture and epithelial distribution. The turbinates—primarily composed of the maxilloturbinate and ethmoturbinate—expand the intranasal surface area and provide a structural foundation for epithelial types. Although the common marmoset(Callithrix jacchus) is widely used as a nonhuman primate model in translational research, postnatal nasal turbinate structure and epithelial zonation have not been fully characterized. In this study, we compared turbinate morphology and epithelial zonation between infant (≤ postnatal day 28) and adult (> 1 year) marmosets using high-resolution micro-computed tomography and histological analysis. In infancy, the maxilloturbinate lacks the scroll-like structure of adults, and The ethmoturbinate is limited in anterior extension and shows no evident branching, indicating immaturity. Epithelial zonation is already characterized in infancy, resembling the adult pattern. The nasal cavity epithelia comprise squamous epithelium (SE), nasal transitional epithelium (TE), respiratory epithelium (RE), and olfactory epithelium (OE) in anterior-to-posterior order. In contrast to adults, infant SE shows high proliferative activity, while RE exhibits sparse goblet cells, reflecting functional immaturity. These findings provide the first developmental map of turbinate architecture and epithelial distribution in the marmoset and serve as a reference for future studies of primate nasal biology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nasal cavity plays an essential role in air humidification, filtration, and olfaction1. These physiological functions are intricately linked to the anatomical complexity of the nasal turbinate and the regionally distinct distribution of epithelial types, including squamous epithelium (SE), nasal transitional epithelium (TE), respiratory epithelium (RE), and olfactory epithelium (OE)2. In mammals, the distribution and development of this epithelial zonation and turbinate structure are species-specific and undergo dynamic changes during early postnatal growth3,4,5. Understanding these developmental processes is fundamental for modeling respiratory function.

The common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) is a Platyrrhine that is increasingly utilized in developmental biology due to its short gestation, rapid maturation, and phylogenetic proximity to humans6. Its nasal cavity is primarily composed of two major turbinates: the maxilloturbinate and ethmoturbinate7. The ethmoturbinate is located in the posterior region adjacent to the cranium and contains both OE and RE, while the maxilloturbinate lies ventrally and is predominantly covered by RE7,8,9. These turbinate structures regulate airflow and increase the mucosal surface area, enhancing mucous secretion and particle capture2,10. Previous anatomical and comparative studies have described the turbinate morphology and epithelial distribution of adult marmosets6,9,10,11. These studies consistently report that marmosets possess simple, planar turbinate structures, characterized by limited branching of the maxilloturbinate and only modest ethmoturbinate development6. This simplified architecture corresponds to a reduced olfactory recess and a relatively small OE surface area compared with other primates9,10. Furthermore, marmosets show reduction of the OE that is confined to the posterior nasal cavity, defining a distinctive nasal epithelial organization11.

Building on these anatomical findings, the present study aims to characterize the turbinate morphology and epithelial zonation in infant marmosets, providing insights into how adult nasal patterns emerge during early postnatal development. To achieve this, we employed high-resolution micro-CT imaging together with histochemical and immunohistochemical staining. We also conducted comparative analyses with cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) to examine interspecies differences in nasal structure and epithelial distribution. Based on these results, we propose standardized coronal sectioning landmarks that capture all four epithelial types (SE, TE, RE, and OE) and establish essential anatomical criteria for the marmoset nasal cavity as a reference for future studies in respiratory biology and comparative anatomy.

Results

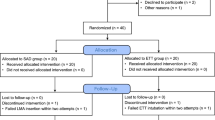

Postnatal maturation of turbinate architecture in the marmoset nasal cavity

To elucidate the postnatal development of turbinate structures in the common marmoset, high-resolution micro-CT imaging was performed on individuals at three age stages: neonatal (< 14 days), infant (2–3 weeks), and adult (> 1 year)—with three individuals examined in each group (n = 9 total; Fig. 1A–C). Three marmosets were examined in each group. No sex-related differences were observed, and representative coronal planes from each age group were selected to illustrate the anatomical features. Coronal sections were acquired at five anatomical levels, beginning between the second incisor and the canine (I2/C) and ending between the fourth premolar and the first molar (P4/M1). In the early postnatal period, the maxilloturbinate lacks a well-developed scroll-like structure, showing sufficient anterior extension but limited posterior extension (Fig. 1A-B, D), Whereas the ethmoturbinate is smaller, unbranched, and does not extend far anteriorly (Fig. 1A–B, D). As development progresses into adulthood, the maxilloturbinate acquires a more pronounced scroll-like morphology and extends further posteriorly, while the ethmoturbinate becomes larger, shows visible branching, and extends further anteriorly (Fig. 1C, D).

Postnatal maturation of turbinate architecture in the marmoset nasal cavity. (A–C) Representative coronal micro-CT images of the marmoset nasal cavity at three stages: neonatal (< 14 days; A), infant (2–3 weeks; B), and adult (> 1 year; C). Coronal sections were obtained at five anatomical levels defined by interdental region: I2/C (between the second incisor and canine), C/P2 (between the canine and second premolar), P2/P3 (between the second and third premolars), P3/P4 (between the third and fourth premolars), and P4/M1 (between the fourth premolar and first molar). Yellow and green lines indicate the maxilloturbinate and ethmoturbinate, respectively. A red arrowhead in the P3/P4 section denotes the presence of a paranasal sinus. Scale bars = 2 mm. (D) Sagittal views of dissected nasal cavities from infant (female, PND4) and adult (male, 1 year old) marmosets, with the maxilloturbinate and ethmoturbinate labeled. Black arrows indicate the approximate coronal sectioning planes shown in A–C. Scale bars = 0.5 cm.

Notably, when sections are taken at equivalent interdental regions, adults exhibit more elaborate turbinate structures extending into the posterior nasal cavity than early postnatal individuals, likely reflecting growth-associated expansion of nasal cavity volume and length during craniofacial development (Fig. 1A–C). Additionally, the nasal sinuses—visible as air-filled spaces within the maxilla and observed at the P3/P4 levels—are more expanded in adults, reflecting greater paranasal cavity development at later stages (Fig. 1A–C). The nasal cavity undergoes continuous remodeling throughout infancy, with progressive increases in turbinate size and internal complexity. These findings suggest that both the maxilloturbinate and ethmoturbinate in marmosets undergo postnatal structural maturation.

Postnatal maturation and zonation of nasal epithelium in the marmoset

To assess postnatal epithelial maturation in the marmoset nasal cavity, we performed coronal micro-CT imaging and histological analysis from early neonatal to adult periods (Figs. 2, 3, 4). Distinct epithelial types—stratified SE, RE, TE and OE—were identified based on anatomical location and histological characteristics. SE was observed in Sect. 1, which corresponds to the region between I1 and I2 in neonates and between I2 and C in infants and adults, and is composed of basal cells aligned along the basement membrane, an intermediate layer of spinous cells, and multiple layers of squamous cells. (Fig. 2A-C, Sect. 1). TE was observed in Sect. 1 at the interface between SE and RE (Fig. 2A–C). It consisted of nonciliated low cuboidal to columnar cells with occasional goblet cells, consistent with the typical features of TE. RE appeared in Sect. 1 and in Sect. 2, which corresponds to C–P2 in neonates and P2–P3 in infants and adults, lining the turbinate surfaces. It is a pseudostratified, cuboidal to columnar, ciliated epithelium with scattered goblet cells (Fig. 2A-C). The OE was confined to Sect. 2. It is a pseudostratified, columnar neuroepithelium containing three principal epithelial cell types: olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs), basal cells, and sustentacular cells (Fig. 2A-C, Sect. 2).

Epithelium in the marmoset nasal cavity across postnatal period. (A–C) Coronal views of the nasal cavity at two anatomical levels in neonatal (< 14 days), infant (2–3 weeks), and adult (> 1 year) marmosets. Section 1 corresponds to the I1/I2 level in neonates and the I2/C level in infants and adults, whereas Sect. 2 corresponds to the C/P2 level in neonates and the P2/P3 level in infants and adults. Micro-CT, schematic illustrations, and H&E staining depict the spatial distribution of stratified squamous epithelium (SE, orange arrow), transitional epithelium (TE, green arrow), respiratory epithelium (RE, blue arrow), and olfactory epithelium (OE, red arrow). Scale bars = 2 mm (CT images in A-C), 1 mm (low-magnification), 20 µm (high-magnification).

Age-related changes in turbinate structure and epithelial distribution in the marmoset nasal cavity. (A, C, E) Color-coded epithelial maps generated from coronal micro-CT images of marmoset nasal cavities at three postnatal stages—neonatal (< 14 days), infant (2–3 weeks), and adult (> 1 year)—across five representative anatomical levels (I2/C to P4/M1). Epithelial types are color-coded as follows: squamous epithelium (SE, orange), transitional epithelium (TE, Green), respiratory epithelium (RE, blue), and olfactory epithelium (OE, red). Scale bars = 2 mm. (B, D, F) Diagram of the epithelial population corresponding to each age group. Orange lines indicate the approximate coronal sectioning planes shown in A, C, and E.

Even at the neonatal stage (< 14 days), when the turbinate structures remained simple and immature, distinct epithelial zonation was already spatially established (Fig. 3A). The anterior region of the nasal vestibule was lined with stratified SE, which gradually transitioned into TE and then into RE along the turbinate surfaces (Fig. 3A–C). The OE was confined to the dorsoposterior region of the nasal cavity from birth, and this restricted zonation persisted throughout development (Fig. 3A–C). This early epithelial zonation in neonatal marmoset was visualized through a color-coded diagram based on five anatomical levels defined by dental positions, ranging from I2/C to P4/M1 (Fig. 3A–C). Turbinate structures—particularly within the ethmoturbinate region—became increasingly branched and folded, resulting in greater structural complexity and an expanded epithelial surface area exposed to airflow (Fig. 3A, C, E). As the marmosets progressed to the infant (2–3 weeks) and adult (> 1 year) stages, the nasal sinus became increasingly developed (Fig. 3A-C). In adults, it appeared as a prominent air-filled cavity on coronal sections, reflecting structural maturation and expansion of the upper airway (Fig. 3A-C). Diagrams of the turbinate and epithelial distribution, along with serial H&E sections, further confirmed that despite increased turbinate complexity with age, the relative spatial positioning of SE, TE, RE, and OE remained consistent (Fig. 2, 3).

However, at the cellular level, neonatal marmosets showed the highest number of Ki67-positive cells in SE, moderate levels in TE, and low levels in both RE and OE (Fig. 4A–C, Supplementary Figure S1A–C). Ki67-positive cells decreased further in infants, and in adults they were rarely detected across all epithelial types (Fig. 4A–C, Supplementary Figure S1A–C). In RE, Alcian blue–PAS staining revealed that goblet cells were sparsely distributed and weakly stained in neonates but became more abundant in infants and adults (Fig. 4A–C). Collectively, these findings indicate that in infant marmosets, epithelial zonation is already established; however, the epithelium is not fully differentiated and is characterized by persistent cell proliferation and fewer goblet cells.

Species-specific patterns of nasal epithelial zonation in adult primates

To assess interspecies variation in nasal epithelial organization, we compared adult common marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys using a multimodal approach combining sagittal and coronal micro-CT, histology, and a diagram of the epithelial population (Fig. 5). In cynomolgus monkeys, seven coronal sectioning levels (#1–7) are evaluated based on interdental regions from incisors to molars—ranging from the region between the central incisor and first premolar (IC/P1) to the region between the first and second molars (M1/M2)—on sagittal CT images (Fig. 5A). Histological analysis revealed that cynomolgus monkeys, like marmosets, exhibit four major epithelial types within the nasal cavity: stratified SE, TE, RE, and OE (Fig. 5B). SE is located in the anterior vestibular region and consists of basal cells aligned along the basal lamina and multiple layers of squamous cells (Fig. 5B). TE formed a narrow transitional zone between SE and RE (Fig. 5B). RE, a pseudostratified, ciliated epithelium with cuboidal to columnar morphology, lined both anterior and posterior turbinate surfaces (Fig. 5B). OE was confined to the dorsal-posterior nasal cavity and is characterized as a pseudostratified, columnar neuroepithelium containing OSNs, basal cells, and sustentacular cells (Fig. 5B). In anterior sections (#2), only SE, TE, and RE are observed, whereas OE is absent (Fig. 5B–C). In section #4, RE is the only epithelial type present. In contrast, posterior sections (#5–7) exhibit both RE and OE (Fig. 5C). Epithelial zonation revealed differences in the relative proportions of each epithelial type between common marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys, primarily due to differences in nasal cavity size and cranial morphology (Fig. 5C–D). In addition to differences in craniofacial morphology, the cynomolgus monkey, unlike the common marmoset, exhibited no branching structures in the ethmoturbinate, and the maxilloturbinate also displayed a simpler morphology with less developed scroll-like structures (Fig. 5C–D). However, the sequential organization of epithelial types—from SE anteriorly to OE posteriorly—is conserved across species, indicating that common spatial zonation is a shared feature among primates. These findings demonstrate that the fundamental pattern of nasal epithelial zonation is preserved between marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys, despite interspecies anatomical variations.

Comparative analysis of nasal cavity structure and epithelial distribution between marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys. (A) Sagittal CT image of an adult cynomolgus monkey head showing seven coronal section levels (#1–7) based on the interdental region. (B) Coronal CT and H&E images at two levels (between C1 and P1 = #2, between M1 and M2 = #5) showing SE (red arrowhead), TE (green arrow), RE (blue arrow), and limited OE (orange arrowhead) distribution in the dorsal-posterior nasal cavity. Scale bars = 2 mm (micro-CT image), 500 µm (low-magnification), 20 µm (high-magnification). (C) Epithelial maps (sections #1–7) showing the distribution of SE (orange), TE (Green), RE (blue), and OE (red). Scale bars = 5 mm. (D) Diagram of the epithelial population in adult cynomolgus (left) and marmoset (right). Numbers above each diagram indicate the relative proportion of each epithelial type (SE, RE, TE, OE). Scale bars = 1 cm.

Establishment of a standardized trimming protocol for comparative nasal histology

To enhance the consistency and reproducibility of the histological evaluation of the nasal cavities across individuals and species, we have established a standardized trimming protocol based on interdental regions. This approach enables consistent inclusion of all four epithelial types—SE, TE, RE, and OE—as well as both the maxilloturbinate and ethmoturbinate within a limited number of coronal sections. In cynomolgus monkeys, two sectioning planes were defined between the canine (C) and the first premolar (P1) based on gross anatomical inspection (Fig. 6A). Section 1 captured the nasal vestibule and anterior turbinate containing SE, TE, and RE, whereas Sect. 2 corresponded to the region between the molar (M) and second molar (M2), targeting the dorsal turbinate and posterior septum where RE and OE were distributed. Paraffin blocks and corresponding histological sections confirmed that this two-level section included all representative epithelial types—SE, TE, RE, and OE—within the nasal cavity (Fig. 5C, E). For marmosets, trimming levels were adapted to the smaller craniofacial proportions of the species (Fig. 6B). Section 1 was placed between the second incisor (I2) and the canine (C), and Sect. 2 was placed between the second and third premolars (P2–P3). These trimming levels effectively captured SE, TE, and RE at the anterior level and RE and OE at the posterior level, as verified by paraffin sections and epithelial distribution maps (Fig. 6D, F). This two-plane trimming strategy reduced the number of sections required for full epithelial assessment while ensuring the inclusion of all epithelial types—SE, TE, RE, and OE. This two-plane trimming strategy is particularly advantageous for studies in comparative anatomy involving high sample throughput. Moreover, the protocol accommodates interspecies morphological differences while maintaining the consistent inclusion of representative epithelial regions. Collectively, these results establish a practical trimming guideline for standardized nasal cavity histology in nonhuman primates, facilitating reproducibility in both developmental and cross-species comparative studies.

Standardized trimming protocol for histological analysis of the nasal cavity in Cynomolgus monkey and Marmoset. (A, B) Sagittal gross images of the nasal cavity in Cynomolgus monkey (Female, 5.5 years) and Marmoset (Male, 1 year old), showing two trimming planes indicated by orange dashed boxes based on the external interdental region. For histological processing, the nasal cavity is trimmed along these planes, with the posterior surface oriented downward. Scale bars = 1 cm (C, D) Representative paraffin blocks and trimmed coronal sections at each level (#1 and #2) in Cynomolgus (C) and Marmoset (D). (E, F) Schematic diagrams of epithelial distribution in each section of Cynomolgus (E) and Marmoset (F), color-coded as follows: stratified squamous epithelium (SE, orange), transitional epithelium (TE, yellow), respiratory epithelium (RE, blue), and olfactory epithelium (OE, orange).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to establish a histological criterion for nasal research by characterizing the postnatal maturation of the turbinate architecture and epithelial zonation in the common marmoset. High-resolution micro-CT analysis revealed that neonatal marmosets possessed short turbinate lacking the characteristic scroll-like morphology, indicating structural immaturity. In adult marmosets, the ethmoturbinate extends anteriorly with prominent branching, and the maxilloturbinate develops a clearly defined scroll-like morphology. This indicates that turbinate structures are considerably simpler in infancy than in adulthood, a pattern that parallels observations in humans, where neonates and infants also exhibit less complex turbinate morphology than children and adults12.

Histological analysis revealed differences between the nasal epithelium of infant and adult marmosets. In adult marmosets, the anterior nasal vestibule is lined by stratified SE, followed by a narrow band of nasal transitional epithelium (TE) and then pseudostratified RE covering the turbinate and septum7,13. The OE is located in the dorsoposterior nasal cavity in all species examined, including marmosets, cynomolgus monkeys, and rodents13,14. Adult marmosets also showed an increase in the density of well-developed goblet cells within RE, resembling the epithelial features of juvenile rats aged 1–7 days4. Proliferation patterns further distinguished the two age groups: neonates demonstrated strong Ki67 positivity in SE, moderate levels in TE, and similarly low activity in both RE and OE, whereas adults showed minimal Ki67 expression across all epithelial types.

Comparative anatomical analysis indicates that adult cynomolgus monkeys, like marmosets, possess only an maxilloturbinate and an ethmoturbinate in each nasal cavity, arranged dorsoventrally in a simplified human-like configuration. In both adult marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys, turbinates are flat and lack complex branching structures, indicating a shared pattern of simplified turbinate morphology in the primate species10. In contrast, rodents exhibit highly elaborate turbinate structures, including multiple nasoturbinates and maxilloturbinates with extensive folding and branching13. Despite species-specific differences in turbinate complexity, the overall pattern of epithelial zonation is conserved across marmosets, cynomolgus monkeys, and rodents6,14. However, in rodents, the OE covered a broader area, extending across multiple ethmoturbinates6,14. This broader distribution in rodents is thought to reflect evolutionary adaptation for acute olfaction, as their nasal cavity is dominated by highly complex ethmoturbinates lined predominantly by olfactory neuroepithelium, unlike the relatively simple turbinate structures in primates14.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that epithelial zonation in the marmoset nasal cavity is spatially established at birth and undergoes progressive structural and cellular maturation postnatally. In addition, although histological trimming approaches for the nasal cavities of marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys have been described in previous studies, the need for practical and standardized trimming guidelines prompted us to propose two additional coronal trimming levels based on interdental anatomical landmarks. These trimming levels consistently include all four major epithelial types—SE, TE, RE, and OE—and can enhance their applicability in developmental and comparative studies. These findings highlight the utility of the common marmoset as a reliable primate model for studying nasal development and support its application in future anatomical investigations.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH-IACUC; Approval Nos.: 22–0250, 24–0226, and 23–0029-S1A2). Animals were housed and cared for in facilities accredited by AAALAC International (Accreditation No.: 001169) in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 8th edition.

This study is reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Animal models

Craniofacial tissues from common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) and a cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) were provided by Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH). A total of nine marmosets were included in this study, consisting of three neonates (PND4–PND6; 2 females, 1 male), three infants (PND15–PND22; 2 females, 1 male), and three adults (1–3 years; 1 female, 2 males). Common marmosets were originally sourced from CLEA Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). Adult tissues were collected from animals used in a previously IACUC-approved study at SNUH (Approval No.: 22–0250). Infant tissues were obtained from naturally culled animals with low viability, a frequent occurrence in marmoset litters, under IACUC-approved husbandry protocols (Approval No.: 24–0226). One cynomolgus monkey (67-month-old female) was obtained from Orient Bio Inc. (Seongnam, Korea), and its tissues were collected under a separate IACUC-approved study at SNUH (Approval No.: 23–0029-S1A2). The present study exclusively used previously collected tissues, with no additional animal procedures performed.

Anesthesia and euthanasia

Animals were anesthetized with inhalation of isoflurane (1–5%) in oxygen (1–4%) via a face mask until surgical depth of anesthesia was achieved. Following anesthesia, euthanasia was performed by exsanguination through the caudal vena cava under deep isoflurane anesthesia.

Micro-computed tomography

Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) was performed using the Quantum GX II Micro-CT imaging system (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) located at the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Seoul National University (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Heads from postmortem common marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, were scanned to visualize the nasal cavity and turbinate structures in situ. Each specimen was positioned in the scanner chamber with the nasal region aligned along the imaging axis. Scans were acquired under the following parameters optimized for high-resolution anatomical imaging of fixed tissue, with a tube voltage of 90 kV and a tube current of 88 μA. Each projection was exposed for 15 min, producing voxel sizes ranging from 25 to 72 μm isotropic. Images were collected with a rotation step of 0.5°, and the total scan time was approximately 30 min per specimen. Acquired projection images were reconstructed into 3D volumetric datasets using PerkinElmer’s reconstruction software with beam hardening correction. Reconstructed volumes were analyzed using 3D Slicer (v5.2.2) and Dragonfly (Object Research Systems) to segment the turbinate structures and identify epithelial boundaries. Coronal planes were extracted to guide subsequent histological sectioning and epithelial zonation analysis.

Histopathology

Heads from common marmosets and cynomolgus monkeys were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF) immediately after necropsy. Samples were subsequently decalcified using 10% formic acid—1–2 days for marmoset specimens and 5–10 days for cynomolgus specimens—depending on skull thickness. Following decalcification, the tissues were processed for routine paraffin embedding. Serial 3 μm-thick paraffin sections were obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Alcian blue–periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS), and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining, using standard protocols. The slides were mounted with resinous mounting media. Histological images were examined using light microscopy, and epithelial zonation was analyzed along standardized coronal trimming levels.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Paraffin-embedded nasal tissue Sects. (3 μm thick) were first baked at 60 °C for 30 min, deparaffinized with xylene, and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 90%, 70%). Sections were then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard protocols. After staining, slides were mounted with resinous mounting medium and examined using SlideViewer (3DHISTECH, Budapest, Hungary) to evaluate overall tissue morphology.

Immunohistochemistry staining

For immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, heat-induced antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6.0, C9999, Sigma-Aldrich), followed by endogenous peroxidase blocking with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide (H325-500-AL, Fisher Chemical, Waltham, MA, USA). Sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody against Ki-67 (1:400, ab16667, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in a humidified chamber. The next day, slides were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (ImmPRESS® HRP polymer detection kit, MP-7402, Vector Laboratories, Newark, CA, USA). Immunoreactivity was visualized using 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB; SK-4105, Vector Laboratories), followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin (H-3404–100, Vector Laboratories). The slides were mounted with resinous mounting media. The number and distribution of Ki-67–positive nuclei were assessed to evaluate epithelial proliferation across developmental stages. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibody.

Alcian blue–PAS

To visualize neutral and acidic mucins in the respiratory epithelium, Alcian blue–Periodic acid–Schiff (AB–PAS) staining was performed on paraffin-embedded nasal Sects. (3 μm thick). Sections were baked at 60 °C for 30 min, deparaffinized with xylene, and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%–70%). Tissues were stained with 1% Alcian blue (in 3% acetic acid; Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min, rinsed, and oxidized in 0.5% periodic acid for 5 min. After washing, the sections were treated with Schiff’s reagent (PAS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min. Nuclear counterstaining was performed using Gill’s hematoxylin (1:1 dilution), followed by differentiation in 0.02% ammonia water. The slides were dehydrated, cleared in xylene, and mounted. Acidic mucins stained blue, neutral mucins magenta, and mixed mucins purple. Goblet cell distribution and mucin composition were evaluated using light microscopy.

Data availability

Representative micro-CT datasets from each developmental stage (Neonatal, < 14 days; Infant, 2–3 weeks; Adult, > 1 year) have been deposited in the Figshare repository [https://figshare.com/articles/figure/Marmoset_micro-CT_scan_data/30189844]. The remaining datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Newsome, H., L. Lin, E., Poetker, D. M. & Garcia, G. J. Clinical importance of nasal air conditioning: a review of the literature. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 33, 763–769. (2019).

Harkema, J. R., Carey, S. A. & Wagner, J. G. The nose revisited: a brief review of the comparative structure, function, and toxicologic pathology of the nasal epithelium. Toxicol. Pathol. 34, 252–269 (2006).

Yamagiwa, Y., Kurata, M. & Satoh, H. Histological Features of the Nasal Passage in Juvenile Japanese White Rabbits. Toxicol. Pathol. 50, 218–231 (2022).

Parker, G. A. & Picut, C. A. Atlas of histology of the juvenile rat (Academic Press, 2016).

Kim, B.-R., Rha, M.-S., Cho, H.-J., Yoon, J.-H. & Kim, C.-H. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the development of mouse olfactory system from prenatal to postnatal period. Front. Neuroanat. 17, 1157224 (2023).

Inoue, T., Yurimoto, T., Seki, F., Sato, K. & Sasaki, E. The common marmoset in biomedical research: experimental disease models and veterinary management. Exp. Anim. 72, 140–150 (2023).

Wako, K., Hiratsuka, H., Katsuta, O. & Tsuchitani, M. Anatomical structure and surface epithelial distribution in the nasal cavity of the common cotton-eared marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Exp. Anim. 48, 31–36 (1999).

Chamanza, R. et al. Normal anatomy, histology, and spontaneous pathology of the nasal cavity of the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Toxicol. Pathol. 44, 636–654 (2016).

Smith, T. D., Bhatnagar, K. P., Tuladhar, P. & Burrows, A. M. Distribution of olfactory epithelium in the primate nasal cavity: are microsmia and macrosmia valid morphological concepts?. Anatomical Record Part A: Discov. Mol. Cell. Evolut. Biol. 281, 1173–1181 (2004).

Smith, T. D., Eiting, T. P., Bonar, C. J. & Craven, B. A. Nasal morphometry in marmosets: loss and redistribution of olfactory surface area. Anat. Rec. 297, 2093–2104 (2014).

Smith, T. D. et al. Comparative microcomputed tomography and histological study of maxillary pneumatization in four species of new world monkeys: the perinatal period. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 144, 392–410 (2011).

Xi, J., Berlinski, A., Zhou, Y., Greenberg, B. & Ou, X. Breathing resistance and ultrafine particle deposition in nasal–laryngeal airways of a newborn, an infant, a child, and an adult. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40, 2579–2595 (2012).

Treuting, P. M., Dintzis, S. M. & Montine, K. S. Comparative anatomy and histology: a mouse, rat, and human atlas (Academic Press, 2017).

Rouquier, S., Blancher, A. & Giorgi, D. The olfactory receptor gene repertoire in primates and mouse: evidence for reduction of the functional fraction in primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 97, 2870–2874 (2000).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant (23214MFDS256) from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety and by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2024–00443008, No. 2021M3H9A1030260, and No. RS-2024–00443043).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M.Y. and N.Y.L. performed histological staining, micro-computed tomography, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript; J.K. and H.J.C. provided marmoset and cynomolgus samples; H.A.K., S.H.S., Y.J.L., and N.Y.L. performed micro-computed tomography imaging; S.H.L. and D.Y.K. provided critical comments and suggestions; and J.W.P. and B.C.K. conceived and supervised the study as corresponding authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, G.M., Lee, N.Y., Kwak, J. et al. Nasal epithelial zonation and turbinate morphology in infant common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus). Sci Rep 16, 4561 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34599-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34599-8