Abstract

This study aimed to examine the associations between personality traits, structural features of borderline personality organization, and depressive symptoms, and to test whether borderline organization dimensions mediate the links between healthy personality traits and depressive symptoms. An online survey was conducted with 709 participants (M age = 29.6; 67.6% female) who completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the Borderline Personality Inventory (BPI), and the Big Five Markers Questionnaire (IPIP-BFM-50). Data were analyzed using Pearson’s correlations and a generalized linear model (GLM) approach for multiple mediation analysis, controlling for gender. Level of depressive symptoms was strongly associated with lower levels of adaptive personality traits and higher levels of structural features of borderline personality organization. Mediation analyses revealed that primitive defenses and fear of fusion consistently mediated the relationships between most personality traits (especially emotional stability) and depressive symptoms, underscoring their central role as indirect pathways of vulnerability. These findings highlight the central role of low emotional stability and associated structural features of borderline personality organization—particularly primitive defenses and fear of fusion—in shaping depressive symptoms, emphasizing key clinical targets for intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A growing body of research has examined the links between personality traits—both normal and maladaptive—and various forms of psychopathology. While many studies have focused on associations between traits and personality disorders (PDs)1, others have investigated their relationship with such disorders as depression, anxiety, and substance use2,3,4. Importantly, the association between PDs and emotional disorders is well established and reflects not only the high rates of comorbidity between these conditions but also the growing recognition of the importance of routinely assessing personality functioning in individuals with symptom disorders, given its known impact on treatment outcomes5,6,7. However, the directionality of the relationship between PDs and symptom disorders remains complex. Research on the association between PDs and depressive symptoms has shown that individuals with PDs frequently experience mood-related symptoms, including depression8, while patients diagnosed with depression often meet criteria for a comorbid PD—most commonly borderline personality disorder9,10,11. Some studies suggest that affective disorders—particularly recurrent depressive episodes—may precede or contribute to the development of BPD8,12, while others indicate that BPD itself may predict the onset or exacerbation of depressive symptoms13. These ambiguities may stem from shared etiological mechanisms. Beatson and Rao14 argue that the episodic nature of depression in individuals with borderline PD, combined with overlapping risk factors—such as emotional dysregulation, neuroticism, and early trauma15,16,17,18—may blur diagnostic boundaries and complicate differential diagnosis.

Personality traits and their relation to psychopathology

The introduction of the Five-Factor Model (FFM) enabled the description of personality through five broad domains: neuroticism (vs. emotional stability), extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. These traits are considered relatively stable across time19, with their developmental course generally predictable and shaped by both genetic and environmental influences20,21,22. These traits are not only key determinants of psychological functioning across various life domains23 but are also closely linked to mental health conditions, including personality disorders and symptom disorders (emotional disorders). Notably, neuroticism has been proposed as a transdiagnostic factor24, positively associated with a wide range of psychiatric disorders3, and regarded as a general vulnerability marker for psychopathology, including depressive disorders (e.g., 4,25). In personality disorders, a typical trait configuration often includes elevated neuroticism and reduced conscientiousness and agreeableness26. The clinical relevance of personality traits is further emphasized in dimensional diagnostic systems such as the Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (AMPD), where Criterion B—maladaptive traits—is conceptualized as a pathological variant of the Big Five domains.

Empirical research supports the clinical relevance of personality traits in emotional disorders, especially depression. Cuijpers et al. 2, in a large study of 640 outpatients, found that while personality traits significantly differentiated individuals with mood and anxiety disorders from the general population, differences between specific diagnoses were minimal; instead, neuroticism and agreeableness were most strongly associated with the level of comorbidity, suggesting that personality traits may reflect a general vulnerability rather than disorder-specific patterns. Additional studies on the Five-Factor Model confirm the robust link between high neuroticism and depressive symptoms3,27. Complementing this, research on maladaptive traits has further clarified these associations. Gioletti and Bornstein’s28 meta-analysis confirmed that they significantly predict symptom disorders, with the strongest associations observed for Negative Affectivity and Detachment. Other studies have demonstrated that maladaptive traits mediate the relationship between early adversity and internalizing symptoms29 and are linked to cognitive vulnerabilities for depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms30. Further findings indicate strong associations between depressive symptoms and internalizing traits—especially elevated Negative Affectivity (or Neuroticism) and Detachment—while other traits like Disinhibition (or low Conscientiousness), Psychoticism, and Antagonism show weaker but noteworthy links to emotional disorders31,32.

While trait-based models of personality have advanced our understanding of psychopathology and clinical assessment, several limitations of this approach have been highlighted33. Clinical interventions typically do not focus on traits in isolation, but rather on the triggers and contextual factors that cause a predisposition to manifest as maladaptive behavior. This highlights the importance of evaluating not only the intensity of a trait itself but also the mediating factors that may shape its potential clinical manifestation. This principle is emphasized in the ICD-11 model of personality disorders34, where the assessment of maladaptive traits is only diagnostically meaningful if the individual meets the threshold for impaired personality functioning.

Personality organization as a mediator of the relationship between personality traits and depression

Personality organization is a psychodynamic construct used to conceptualize the level of personality functioning within dimensional models of personality disorders, rooted in Kernberg’s object relations theory35,36. Previous work has highlighted the close theoretical and clinical connections between object relations theory and the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders, noting considerable overlap between the domains of functioning defined in Criterion A of the AMPD and those emphasized in the concept of personality organization35. While the AMPD and other dimensional models of PD, such as ICD-1134, provide a descriptive trait-based dimensional framework, the object relations approach offers a structural theoretical context for understanding and assessing personality disorders. In object relations theory, personality is seen as a dynamic integration of behavioral patterns and internal experiences, shaped by internalized representations of self–object relations37,38. Central to this model is the concept of personality organization, which spans a continuum from healthy to severely impaired structural functioning. This framework conceptualizes personality structure along key dimensions: identity integration, predominant defense mechanisms, reality testing, object relations, and moral functioning. Each level of personality organization is associated with a distinct style of emotional regulation and specific symptom expression. Higher levels, characterized by neurotic defenses such as repression, tend to produce rigid but stable functioning that may be linked with persistent depressive or anxiety symptoms37. In contrast, lower levels rely on primitive defenses (e.g., splitting), which distort internal and external reality, contributing to more severe affective instability and depressive episodes, especially under stress or decompensation that may be followed by self-harm, suicidal ideation, or acting-out behaviors37,39. Thus, personality organization dimensions are critical factors in understanding the severity and phenomenology of depressive symptoms across individuals. Indeed, research supports the clinical relevance of this model not only in the context of personality disorders but also in emotional disorders: structural aspects of borderline personality organization have been shown to correlate with the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals with PDs39,40,41,42, anxiety in general and clinical populations5,6,7, as well as with general psychological distress and level of mentalizing43,44.

Within contemporary personality psychology, adaptive trait models offer a descriptive account of stable dispositional tendencies, while psychodynamic theories—particularly Kernberg’s model of personality organization—provide a structural framework for understanding the underlying mechanisms that shape personality functioning and psychopathology. Empirical studies directly examining the relationship between adaptive FFM traits and structural features of personality organization remain scarce. Available findings indicate a coherent pattern of associations: lower identity integration, poorer object relations, and a greater reliance on primitive defenses are linked with higher Neuroticism and lower Agreeableness and Conscientiousness, whereas Extraversion and Openness show little to no association45. These relationships, typically of low to moderate strength, suggest that adaptive traits covary with structural functioning but remain conceptually distinct constructs. Parallel lines of research have examined maladaptive trait domains (as defined in the DSM-5 AMPD and ICD-11 models) in relation to personality organization; however, these studies are few and have yielded weak and heterogeneous correlations46 This gap underscores the need to investigate how adaptive personality traits may contribute to vulnerability toward psychopathological outcomes through their links with structural aspects of personality functioning.

In Kernberg’s extension of object relations theory, emotional reactivity is viewed as part of a broader temperamental disposition that constitutes a biological foundation of personality organization47. From this perspective, variations in affective reactivity influence how individuals respond to internal and external stimuli, including their emotional thresholds38. High emotional reactivity may contribute directly to depressive symptoms, but it may also hinder the development of integrated personality structures. For instance, it can prevent the resolution of primitive defenses such as splitting and obstruct the formation of stable, positive internal object relations, both of which are protective against depressive vulnerability. This suggests that depressive symptoms may arise not only from personality traits but also through impaired personality organization. Individuals with lower levels of personality organization may be more vulnerable to depression due to structural deficits shaped by emotional reactivity. This psychodynamic view highlights the need to assess both traits and personality organization when understanding depressive symptoms and supports the hypothesis that structural deficits in personality organization may serve as a pathway through which low emotional stability and other adaptive traits translate into depressive symptomatology.

Current study

This study has two main aims: (a) to replicate the well-established associations between personality traits (trait-level dispositions) and depressive symptoms, and (b) to test whether structural features of borderline personality organization (reflecting personality-structure functioning rather than symptoms) mediate the relationships between adaptive personality traits and depressive symptoms. To date, no studies have comprehensively examined these variables together as a unified set of factors linked to depressive symptoms within the object relations clinical framework, which suggests that core personality traits, especially emotional instability (neuroticism), lay the foundation for the development of structural impairments that elevate depression risk. This integrated perspective provides a more complete picture of personality-based risk factors for depressive symptoms. We hypothesize that lower levels of adaptive personality traits (emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, intellect, extraversion) and higher levels of structural features of borderline personality organization (primitive defenses, identity diffusion, fear of fusion, impaired reality testing) will be associated with increased depressive symptoms. We also expect that the link between adaptive personality traits, particularly emotional (un)stability, and depressive symptoms will be mediated by these structural mediators (BPI dimensions reflecting borderline personality organization; see Fig. 1). This mediation hypothesis reflects the idea that borderline personality structures, shaped by constitutional predispositions and environmental influences, act as key mechanisms through which personality traits translate into depressive symptoms. Testing these unique mediating roles of Kernberg’s structural dimensions of borderline personality organization is a novel and exploratory aspect of this study. It clarifies which aspects of structural features of borderline personality organization, rooted in core traits, pose the greatest risk for heightened levels of depressive symptoms and thus merit targeted psychotherapeutic interventions.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study involved 709 participants (gender: n = 479 women, n = 215 men, n = 15 others) from the general population, aged between 18 and 81 years (M = 29.6, SD = 12.1, Md = 24) (see more in Table 1). Participants were recruited between December 2024 and April 2025 as part of a broader research project focused on the validation of The Splitting Index. Recruitment was conducted through publicly available online announcements and social media posts published on the official websites of the university faculty and the research laboratory leading the project. The recruitment posts and study materials were prepared and distributed by the research team members. The study link was shared in local community groups and national online forums for individuals who self-identified as experiencing psychological difficulties. Examples of such groups included city-based community networks and online forums dedicated to mental health and psychological well-being. In addition, participants were encouraged to share the link further using a snowball sampling approach. The sample was voluntary and based on convenience sampling. Participation began with providing informed consent, followed by completing a short demographic questionnaire and a set of self-report measures, which took approximately 20 min. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant institutional guidelines. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland (Opinion No. 4/12/2024, issued on 10 December 2024). All participants provided informed consent prior to taking part in the study. All research activities described in this manuscript were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable ethical guidelines and regulations for research involving human participants.

Measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-948; Polish adaptation49 was used to assess the level of depressive symptoms (the experience of symptoms characteristic of depression that interfere with daily functioning). The PHQ-9 consists of nine items that correspond to DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for depression. Participants rated the frequency of each symptom over the past two weeks on a four-point scale (0 = not at all, 1 = Several days, 2 = More than half the days, 3 = nearly every day). In both the Polish validation study and the current study, the internal consistency was high (α = 0.87). Example items include: “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless” and “Feeling tired or having little energy.”

The Borderline Personality Inventory (BPI50; Polish adaptation51; Soroko et al.52) was used to assess the structural dimensions of borderline personality organization reflecting Kernberg’s object relations theory37. The BPI includes subscales that correspond to core structural domains—identity diffusion, primitive defenses, reality testing, and fear of fusion (fear of intimacy). It consists of 53 yes/no statements. Example items include: “My feelings towards other people quickly change into opposite extremes (e.g., from love and admiration to hate and disappointment)”, „If a relationship gets close, I feel trapped.”, „People often appear to me to be hostile.” The Borderline Personality Inventory (BPI) assesses intrapsychic structural features of borderline personality organization (e.g., identity diffusion, primitive defenses, and reality testing). Although some items refer to psychopathological experiences, the instrument does not measure clinical symptomatology but rather structural aspects of personality functioning. In this study, the full scale showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90), with subscale alphas ranging from 0.68 (fear of fusion) to 0.78 (identity diffusion). The questionnaire has demonstrated high validity in previous studies.

The Big Five Markers Questionnaire from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP-BFM-50;53; Polish adaptation:54) was used to assess five personality factors: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability (conceptually analogous to neuroticism in the NEO-PI-R), and intellect (comparable to openness to experience). Cronbach’s α coefficients for the subscales ranged from .77 to .88 in prior studies, and from .79 to .91 in the present study. The questionnaire comprises 50 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = very inaccurate, 5 = very accurate). Example items include: “I change my mood a lot”, "I get chores done right away" and “I don’t mind being the center of attention”.

Data analysis

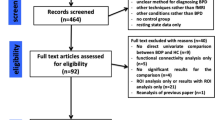

The distribution of variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, skewness values, and visual inspection of histograms. Most variables approached normality, with Shapiro–Wilk statistics ranging from 0.90 to 0.99. An exception was the BPI IRT score (SW = 0.50), although the absolute values of skewness for all variables remained within acceptable limits (below |1.0|). Five univariate outliers were identified but retained, as they did not substantially affect the results. The data were analyzed using a correlational-regression framework. To examine general associations, pairwise Pearson’s r correlations were calculated for all variables, using a large sample size and bootstrap resampling (5000 iterations) to address potential skewness and to provide confidence intervals for the correlation coefficients. Gender differences were assessed with Student’s t-tests for independent samples, accompanied by Cohen’s d effect size estimates and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (5000 trials), addressing potential imbalances due to the overrepresentation of women. Because men and women significantly differed in all study variables, except for extraversion (IPIP) and the reality testing (BPI) dimension of personality pathology, multiple mediation analyses (GLM Mediation Model) were conducted to examine the hypothesized pathways from personality traits to depressive symptoms. In these models, depressive symptoms (PHQ_9) served as the dependent variable; personality traits (IPIP) as independent variables; and structural features of borderline personality organization (identity diffusion, primitive defenses, reality testing, and fear of fusion) as simultaneous mediators. Potential common method bias was evaluated using both Harman’s single-factor test and the full collinearity VIF approach55,56. No substantial bias was detected. Moreover, gender (male vs. female) was included as a binary control variable. Accordingly, fifteen participants who identified as non-binary were excluded from all analyses involving gender, resulting in a final analytic sample of 694 cases. Furthermore, although the cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inferences, this analytic approach was justified by the theoretical assumption that core personality traits precede the development of personality pathology, which in turn contributes to the development of depressive symptoms. This framework is consistent with object relations clinical theory, which posits that maladaptive personality structure (e.g., primitive defenses, identity diffusion) emerges in interaction with emotional reactivity-based personality traits and shapes vulnerability to depressive symptomatology. All analyses were conducted using Jamovi version 2.4.8.

Results

Associations between personality traits, personality organization dimensions, and depressive symptoms

Pearson’s r correlation coefficients (see Table 2 for the full matrix) showed that the level of depressive symptoms was associated in line with the proposed hypotheses: it was positively correlated with all dimensions of (pathological) personality structure and negatively correlated with each of the adaptive personality traits. The strongest observed correlations were between depressive symptoms and emotional stability (IPIP_ES) (r = − .68, p < .001), primitive defenses (BPI_PD) (r = .68, p < .001), identity diffusion (BPI_ID) (r = .59, p < .001), and fear of fusion (BPI_FF) (r = .57, p < .001). A moderate positive association was also observed between depressive symptoms and reality testing (BPI-RT) (r = .33, p < .001). In contrast, the weakest significant association was found between depressive symptoms and intellect (IPIP_I) (r = − .12, p < .05). Furthermore, moderate negative correlations were observed between depressive symptoms and both agreeableness (IPIP_A) (r = − .21, p < .001) and conscientiousness (IPIP_C) (r = − .27, p < .001). Overall, these results underscore a consistent pattern in which higher levels of depressive symptoms are linked to lower levels of adaptive personality traits and higher levels of structural features of borderline personality organization. The structural features themselves showed low to strong positive correlations with each other, while the personality traits also demonstrated generally low to moderate intercorrelations, reflecting the interconnectedness of these constructs within the broader spectrum of personality and psychopathology.

Differences between male and female participants in personality traits, structural features of borderline personality organization, and depressive symptoms

Gender differences were examined in the intensity of personality traits, structural features of borderline personality organization, and depressive symptoms. Only participants identifying as male or female were included in these analyses, and percentile bootstrapping (5000 trials) was used to account for the unequal group sizes. Results revealed small yet consistent gender differences in depressive symptoms, personality functioning, and trait dimensions, as shown in Table 3.

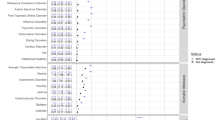

Structural features of borderline personality organization as mediators of the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms

To examine how structural features of borderline personality organization (identity diffusion, primitive defenses, reality testing, and fear of fusion – BPI_ID, BPI_PD, BPI_RT, BPI_FF) mediate the relationship between personality traits and depressive symptoms (PHQ_9), multiple mediation models were tested while controlling for gender (see Table 4). Significant indirect effects were observed for most personality traits, with primitive defenses (BPI_PD) and fear of fusion (BPI_FF) serving as consistent mediators. For example, emotional stability (IPIP_ES) demonstrated strong indirect effects through primitive defenses (BPI_PD) (β = − 0.13, p < .001) and fear of fusion (BPI_FF) (β = − 0.07, p < .001), alongside a robust direct effect (β = − 0.36, p < .001) and the strongest total effect (β = − 0.60, p < .001). Conscientiousness (IPIP_C) showed significant indirect effects via primitive defenses (BPI_PD) (β = − 0.02, p = .004) and fear of fusion (BPI_FF) (β = − 0.03, p < .001), as well as a significant total effect (β = − 0.12, p < .001). Extraversion (IPIP_E) also exhibited significant indirect effects through BPI_PD (β = − 0.02, p = .010) and BPI_FF (β = − 0.02, p = .008), a significant direct effect (β = − 0.09, p = .001), and a significant total effect (β = − 0.14, p < .001). Agreeableness (IPIP_A) had significant indirect effects via BPI_PD (β = − 0.03, p = .001) and BPI_FF (β = − 0.03, p < .001), although no significant direct or total effects were observed. Interestingly, intellect (IPIP_I) showed a significant indirect effect through BPI_FF (β = 0.02, p = .019) but no significant total or direct effects.

Discussion

This study had two main aims: to replicate the associations between personality traits and depressive symptoms, and to test whether structural features of borderline personality organization mediate the relationships between adaptive personality traits and depressive symptoms. As expected, our findings showed that lower levels of adaptive personality traits (emotional stability, agreeableness, conscientiousness, intellect, and extraversion) were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with previous studies, which have demonstrated that depressive disorders are characterized by profiles of low emotional stability, low conscientiousness, and low extraversion2,3,57. Emotional stability emerged as a particularly strong correlate of depressive symptoms. Numerous studies have confirmed this link, showing that individuals with low emotional stability (or its inverse, neuroticism, and its maladaptive variant negative affectivity) are more vulnerable to experiencing mood disorder symptoms16,28. These findings underscore the robust and transdiagnostic role of emotional stability (or neuroticism) as a central personality-based risk factor for depressive symptoms. From a clinical perspective, they support the growing emphasis on integrating trait-level assessment into the diagnostic and therapeutic process—not only for identifying vulnerability to depression, but also for tailoring interventions to individual personality profiles. For example, individuals with low emotional stability may benefit from therapeutic strategies targeting affect regulation, stress tolerance, and cognitive reframing of negative experiences. Moreover, these results validate the utility of the Five-Factor Model in capturing dimensions of personality that are both empirically linked to psychopathology and clinically meaningful. The consistent associations between certain trait configurations—especially low emotional stability, low conscientiousness, and low extraversion—and depressive symptoms suggest that personality traits can serve as important indicators of emotional disorders.

We also found that higher levels of structural features of borderline personality organization –primitive defenses, identity diffusion, fear of fusion, and impaired reality testing—were positively associated with depressive symptoms, in line with previous research indicating that the level of depressive symptoms is linked to lower levels of personality organization39,40,41,42. This finding aligns with contemporary psychodynamic theories, which posit that the tendency to develop depressive reactions reflects an interplay between constitutional vulnerabilities (e.g., genetic and neurobiological predispositions) and environmental factors shaping personality structure58.

Among the structural features of borderline personality organization, identity diffusion, primitive defenses, and fear of fusion were linked to depressive symptoms. These findings are theoretically consistent with Kernberg’s model of personality organization, in which identity diffusion—defined as a lack of a coherent and stable sense of self and others—is considered a central structural deficit in more severe personality pathology37. When individuals cannot maintain stable internal representations, they are more vulnerable to experiencing dysregulated affect, especially in response to interpersonal stress, loss, or perceived rejection—common triggers for depressive episodes38. Primitive defenses such as splitting, idealization, and projective identification also contribute to this vulnerability by disrupting emotional integration and distorting perceptions of self and others37. Building on the work of Freud, Klein, and Jacobson, Kernberg59 conceptualized depression as a manifestation of aggression turned inward after the loss or devaluation of an idealized object—an emotional process often sustained and intensified by the operation of primitive defenses. In individuals who feel isolated, helpless, and perceive the world as overwhelmingly negative, these defenses—coupled with intense relational anxieties—may exacerbate depressive symptoms and hinder the recovery process. Such patterns often sustain fantasies of an idealized, perfectly gratifying world that remains perpetually out of reach, leading to profound disappointment and self-directed hostility—hallmarks of depressive reactions in psychodynamic theory. These may hinder adaptive coping and increase the likelihood of intense and unstable emotional experiences, which may manifest as chronic dysphoria, despair, or self-directed aggression37. Fear of fusion, although less frequently studied, reflects a specific disturbance in interpersonal boundaries and autonomy, often rooted in early attachment disruptions and unresolved dependency needs38. Individuals with a heightened fear of fusion may struggle to maintain a separate, autonomous sense of self in relationships, oscillating between enmeshment and emotional withdrawal—dynamics strongly associated with depressive vulnerability, particularly in the context of interpersonal loss or dependency conflicts38. High fear of fusion may reduce interest in social connections and the possibility of positive reinforcement, which might otherwise counteract depressive isolation. It may also reflect the inability to maintain a close (intrapsychic) relationship with the lost object, experienced as a profound sense of hopelessness or feeling that no one can provide relief.

Taken together, these structural vulnerabilities suggest that the severity of depressive symptoms may stem not only from trait-level emotional instability (e.g., neuroticism or negative affectivity) but also from deeper disruptions in self-coherence, emotion regulation, and interpersonal functioning. This underscores the clinical importance of assessing structural features of personality organization alongside traits, particularly in patients presenting with complex, chronic, or treatment-resistant depressive symptoms.

With respect to the second aim of the study, our mediation results showed that the relationship between low emotional stability and depressive symptoms was mediated by two of the four examined structural features of borderline personality organization: primitive defenses and fear of fusion. This is consistent with Paulus et al. 60, who found that emotional dysregulation and lack of psychological flexibility mediate the link between neuroticism and depression in adolescents. Our findings highlight the specific roles of primitive defenses and fear of fusion as intensifying factors for depressive symptoms, underscoring the clinical relevance of these dimensions. It also supports the hypothesis that biologically rooted personality traits may hinder the development of integrated personality structure (e.g., resolving early developmental splitting during rapprochement phases; see e.g., 37) and adaptive emotional regulation60,61. The most substantial result is the robust indirect and total effects of emotional stability (IPIP_ES) on depressive symptoms (β = −0.60, p < .001), indicating that neuroticism powerfully shapes depressive vulnerability—both directly and through structural features of borderline personality organization. Although the strong association between emotional stability and depressive symptoms aligns with previous research, these are related but conceptually distinct constructs. Neuroticism (the inverse of emotional stability) reflects a broad, trait-like disposition toward negative affectivity, whereas depressive symptoms represent state-dependent emotional experiences typical of clinical conditions24. Therefore, we suggest that the observed relationship reflects a vulnerability mechanism rather than measurement overlap. This suggests that neuroticism not only elevates depression risk but also perpetuates splitting and intensifies negative self/object relations, thus entrenching personality-level patterns of vulnerability. Finally, the consistent mediation effects of primitive defenses and fear of fusion across other personality traits, beyond emotional stability, suggest that these structural features of borderline personality organization act as broad, transdiagnostic mechanisms of risk. Interestingly, impaired reality testing did not emerge as a significant mediator, suggesting that in this general population sample, depressive symptoms may be more strongly tied to defensive functioning and relational anxieties than to reality testing distortions. Importantly, all mediation analyses controlled for gender, ensuring that the observed pathways linking personality traits, structural features of borderline personality organization, and depressive symptoms were not confounded by gender-related variance. This strengthens the validity of our findings and suggests that the identified mechanisms operate consistently across male and female participants.

Viewing these processes as multi-level interactions—where depressive symptoms can arise from structural features of borderline personality organization, themselves shaped by constitutional traits—has important therapeutic implications. While symptom-focused treatments can be effective62, addressing aspects of personality structure and emotional regulation (especially anxiety) may be crucial for long-term recovery. Indeed, personality structural features of borderline personality —particularly splitting—can reinforce the impact of low emotional stability, potentially undermining symptom-focused treatments and leading to symptom recurrence or transformation over time55. These findings underscore the clinical value of assessing aspects of borderline personality structure in patients with depressive symptoms. Given the well-established role of personality functioning in shaping treatment outcomes, its evaluation should be considered an integral component of both diagnostic assessment and treatment planning in individuals presenting with symptomatic disorders6,31.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this multiple mediation approach, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study relied on an online convenience sample drawn from the general population, with an unequal gender distribution that is typical for psychological studies but still limits generalizability. Second, although the theoretical model was grounded in Kernberg’s clinical framework and supported by evolutionary perspectives suggesting that normal personality traits shape an individual’s early ecological niche (e.g.,63), the cross-sectional design precludes causal interpretations of the observed mediation effects64. Third, the inclusion of multiple mediators that were themselves correlated may have introduced multicollinearity, potentially biasing the magnitude or significance of specific indirect paths. Finally, while bootstrapping was employed to address the non-normality of indirect effects, it does not fully resolve the non-normality of residuals within the regression models, although the large sample size in this study partially mitigates this concern. Beyond these methodological considerations, it is important to recognize that the study tested a predisposition model based on clinical object relations theory; however, complementary or competing models, such as those emphasizing reverse or pathoplastic influences, might also account for the associations observed (e.g.,24). Future research should aim to replicate and extend these findings using clinical samples, including individuals diagnosed with depression, personality disorders, or both, and compare them with healthy controls. Moreover, employing a longitudinal design and integrating diverse assessment methods, such as structured clinical interviews (e.g., Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 Alternative Model for Personality Disorders65; or the Structured Interview of Personality Organization–Revised66, would strengthen the clinical validity and theoretical grounding of the tested model.

Conclusions

The present study confirms the central role of emotional stability (and to some extent neuroticism/negative affectivity) as the strongest and most consistent predictor of depressive symptoms, with both direct and indirect pathways through personality pathology dimensions—specifically, primitive defenses and fear of fusion—highlighting its clinical significance. Other personality traits, such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion, also demonstrated significant indirect effects, though to a lesser extent. These findings support the theoretical framework, in which maladaptive personality structures serve as a mediator linking emotional reactivity predispositions to depressive symptoms. Clinically, they underscore the need to address both constitutional vulnerabilities (e.g., low emotional stability) and the associated personality structures (e.g., primitive defenses and fear of fusion) in psychotherapeutic interventions aimed at reducing the level of depressive symptoms.

Data availability

The datasets generated by the survey research during and analyzed during the current study are available in the OSF repository, https://osf.io/hn3aj/.

References

Trull, T. J., Widiger, T. A. & and Dimensional models of personality: the five-factor model and the DSM-5. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 15, 135–146 (2013).

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A. & Donker, M. Personality traits of patients with mood and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 133, 229–237 (2005).

Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F. & Watson, D. Linking big personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 136, 768–821 (2010).

South, S. C., Eaton, N. R. & Krueger, R. F. The connections between personality and psychopathology. in Contemporary Directions in Psychopathology: Scientific Foundations of the DSM-V and ICD-11 242–262 (The Guilford Press, New York, NY, US, (2010).

Doering, S. et al. Personality functioning in anxiety disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 18, 294 (2018).

Gruber, M., Doering, S. & Blüml, V. Personality functioning in anxiety disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 33, 62 (2020).

Górska, D. The role of the level of personality organization in emotional processing in generalized anxiety disorder. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 181, 111020 (2021).

Zanarini, M. C. et al. Axis I Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. AJP 155, 1733–1739 (1998).

Corruble, E., Ginestet, D. & Guelfi, J. D. Comorbidity of personality disorders and unipolar major depression: A review. J. Affect. Disord. 37, 157–170 (1996).

Fava, M. et al. Personality disorders and depression. Psychol. Med. 32, 1049–1057 (2002).

McGlashan, T. H. et al. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatry. Scand. 102, 256–264 (2000).

Skodol, A. E. et al. Co-occurrence of mood and personality disorders: a report from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study (CLPS). Depress. Anxiety. 10, 175–182 (1999).

Skodol, A. E. et al. Relationship of personality disorders to the course of major depressive disorder in a nationally representative sample. AJP 168, 257–264 (2011).

Beatson, J. A. & Rao, S. Depression and borderline personality disorder. Med. J. Aust. 199, S24–S27 (2013).

Klein, D. N. & Schwartz, J. E. The relation between depressive symptoms and borderline personality disorder features over time in dysthymic disorder. J. Personal. Disord. 16, 523–535 (2002).

Widiger, T. A. & Costa, P. T. Jr. Five-factor model personality disorder research. in Personality Disorders and the five-factor Model of Personality, 2nd ed 59–87 (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US, doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/10423-005. (2002).

Lizardi, H. et al. Reports of the childhood home environment in early-onset dysthymia and episodic major depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 104, 132–139 (1995).

Zanarini, M. C. et al. Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 154, 1101–1106 (1997).

Debast, I. et al. Personality traits and personality disorders in late middle and old age: do they remain stable? A literature review. Clin. Gerontologist. 37, 253–271 (2014).

Bleidorn, W., Hopwood, C. J. & Lucas, R. E. Life events and personality trait change. J. Pers. 86, 83–96 (2018).

Specht, J., Egloff, B. & Schmukle, S. C. Stability and change of personality across the life course: the impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the big five. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 101, 862–882 (2011).

Ormel, J. et al. The biological and psychological basis of neuroticism: current status and future directions. Neurosci. Biobehavioral Reviews. 37, 59–72 (2013).

Strelau, J. Różnice Indywidualne 2nd edn (Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, 2022). [in Polish].

Klein, D. N., Kotov, R. & Bufferd, S. J. Personality and depression: explanatory models and review of the evidence. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 7, 269–295 (2011).

Trull, T. J., Widiger, T. A., Lynam, D. R. & CostaJr. P. T. Borderline personality disorder from the perspective of general personality functioning. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 112, 193–202 (2003).

Morey, L. C. et al. Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM–5, part II: empirical articulation of a core dimension of personality pathology. J. Pers. Assess. 93, 347–353 (2011).

Ormel, J. et al. Neuroticism and common mental disorders: meaning and utility of a complex relationship. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33, 686–697 (2013).

Gioletti, A. I., Bornstein, R. F. & Do PID-5 trait scores predict symptom disorders? A Meta-analytic review. J. Personal. Disord. 38, 126–137 (2024).

Bach, B., Bo, S. & Simonsen, E. Maladaptive personality traits May link childhood trauma history to current internalizing symptoms. Scand. J. Psychol. 63, 468–475 (2022).

Hong, R. Y. & Tan, Y. L. DSM-5 personality traits and cognitive risks for depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 169, 110041 (2021).

Jańczak, M. O. & Soroko, E. Level of personality functioning and maladaptive personality traits in relation to depression and anxiety symptoms in middle and older adults. Sci. Rep. 15, 11303 (2025).

Vittengl, J. R., Jarrett, R. B., Ro, E. & Clark, L. A. How can the DSM-5 alternative model of personality disorders advance Understanding of depression? J. Affect. Disord. 320, 254–262 (2023).

Meehan, K. B. & Clarkin, J. F. A critical evaluation of moving toward a trait system for personality disorder assessment. in Personality disorders: Toward theoretical and empirical integration in diagnosis and assessment 85–106American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, US, (2015).

World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en. (accessed 24 Jun 2025).

Clarkin, J. F., Caligor, E. & Sowislo, J. F. An object relations model perspective on the alternative model for personality disorders (DSM-5). Psychopathology 53, 141–148 (2020).

Hörz-Sagstetter, S., Ohse, L. & Kampe, L. Three dimensional approaches to personality disorders: a review on personality Functioning, personality Structure, and personality organization. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 23, 45 (2021).

Caligor, E., Kernberg, O. F., Clarkin, J. F. & Yeomans, F. E. Psychodynamic Therapy for Personality Pathology: Treating Self and Interpersonal Functioning (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2018).

Kernberg, O. F. Treatment of Severe Personality Disorders: Resolution of Aggression and Recovery of Eroticism (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2018).

Kovács, L. N., Schmelowszky, Á., Galambos, A. & Kökönyei, G. Rumination mediates the relationship between personality organization and symptoms of borderline personality disorder and depression. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 168, 110339 (2021).

Jakšić, N., Marčinko, D., Bjedov, S., Mustač, F. & Bilić, V. Personality organization and depressive symptoms among psychiatric outpatients: the mediating role of shame. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 210, 590 (2022).

Lowyck, B., Luyten, P., Verhaest, Y., Vandeneede, B. & Vermote, R. Levels of personality functioning and their association with clinical features and interpersonal functioning in patients with personality disorders. J. Personal. Disord. 27, 320–336 (2013).

Sibilla, F., Imperato, C., Mancini, T. & Musetti, A. The association between level of personality organization and problematic gaming: Anxiety, depression, and motivations for playing as mediators. Addict. Behav. 132, 107368 (2022).

Jańczak, M. O., Soroko, E. & Górska, D. Metacognition and defensive activity in response to relational–emotional stimuli in borderline personality organization. J. Psychother. Integr. 33, 86–101 (2023).

Preti, E. et al. The facets of identity: personality pathology assessment through the inventory of personality organization. Personality Disorders: Theory Res. Treat. 6, 129–140 (2015).

Laverdière, O. et al. Personality Organization, Five-Factor Model, and mental health. J. Nerv. Mental Disease. 195, 819–829 (2007).

Laczkovics, C. et al. Assessment of personality disorders in adolescents: a clinical validity and utility study of the structured interview of personality organization (STIPO). Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment Health. 19, 49 (2025).

Kernberg, O. F. What is personality? J. Pers. Disord. 30, 145–156 (2016).

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B. W. & the Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a Self-report version of PRIME-MDThe PHQ primary care study. JAMA 282, 1737–1744 (1999).

Kokoszka, A., Jastrzębski, A. & Obrębski, M. Ocena psychometrycznych właściwości Polskiej Wersji Kwestionariusza Zdrowia Pacjenta-9 Dla osób dorosłych. Psychiatria 13, 187–193 (2016). [in Polish].

Leichsenring, F. Development and first results of the borderline personality inventory: A self-report instrument for assessing borderline personality organization. J. Pers. Assess. 73, 45–63 (1999).

Cierpiałkowska, L. Polish Adaptation of F. Leichsenring’s Borderline Personality Inventory (Unlublished materials at Adam Mickiewicz University, 2001).

Soroko, E., Kleka, P., Cierpiałkowska, L. & Leichsnenring, F. (in review) Internal Structure, reliability, and gender neutrality of the borderline personality inventory.

Goldberg, L. R. et al. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. J. Res. Pers. 40, 84–96 (2006).

Strus, W., Cieciuch, J. & Rowiński, T. Polska Adaptacja Kwestionariusza IPIP-BFM-50 do Pomiaru pięciu Cech osobowości w ujęciu Leksykalnym. Annals Psychol. 17, 327–346 (2014).

Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: a full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 11, 1–10 (2015).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B. & Podsakoff, N. P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 63, 539–569 (2012).

Malouff, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B. & Schutte, N. S. The relationship between the Five-Factor model of personality and symptoms of clinical disorders: A Meta-Analysis. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 27, 101–114 (2005).

Gabbard, G. O. Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 5th Ed. xiv, 639American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., Arlington, VA, US, (2014).

Kernberg, O. F. An integrated theory of depression. Neuropsychoanalysis 11, 76–80 (2009).

Paulus, D. J., Vanwoerden, S., Norton, P. J. & Sharp, C. Emotion dysregulation, psychological inflexibility, and shame as explanatory factors between neuroticism and depression. J. Affect. Disord. 190, 376–385 (2016).

Kokkonen, M. & Pulkkinen, L. Extraversion and neuroticism as antecendents of emotion regulation in adulthood. Eur. J. Pers. 15, 407–425 (2001).

Gunderson, J. G. et al. Major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder revisited: Longitudinal interactions. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 65, 1049–1056 (2004).

Cheli, S. & Brüne, M. When Do Personality Traits Become Pathological? An Epistemological and Evolutionary View. To Appear in Konrad Banicki and Peter Zachar (Eds) (Cambridge University Press, 2025).

Maxwell, S. E., Cole, D. A. & / & Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods. 12, 23–44 (2007).

Bender, D. S., Skodol, A. E., First, M. B., John, M. & Oldham Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5® Alternative Model for Personality Disorders (SCID-5-AMPD) Module I: Level of Personality Functioning Scale (American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2018).

Clarkin, J. F., Caligor, E., Stern, B. L. & Kernberg, O. F. Manual for the Structured Interview of Personality Organization-Revised (STIPO-R) Unpublished manuscript. Unpublished Manuscript (Weill Cornell Medical College, 2019). https://www.borderlinedisorders.com/assets/STIPORmanual.July2021.pdf

Funding

The author received no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S., J.B., A.W., and M.J. wrote the draft of the main manuscript text. MZ prepared calculations. All authors enhanced the manuscript and reviewed its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soroko, E., Bandel, J., Wesołowski, A. et al. Structural features of borderline personality organization mediate the links between personality traits and depressive symptoms. Sci Rep 16, 4473 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34644-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34644-6