Abstract

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) image object detection plays a crucial role in various fields. However, compared with natural images, UAV images are characterized by significant target scale variations, complex backgrounds, dense small targets, and clustered target distributions, which pose serious challenges to object detection tasks. To address these issues, this study proposes an improved object detection algorithm named MFRA-YOLO, which combines multi-scale feature fusion and receptive-field attention-based convolution, built upon the baseline YOLOv8n algorithm. First, Monte Carlo attention is integrated into receptive-field attention-based convolution to enhance cross-scale information interaction capability, thereby forming a novel convolutional module for downsampling operations. Second, a multi-scale selective fusion module is incorporated into the feature fusion network to enable adaptive cross-scale integration of features. When coupled with the scale sequence feature fusion module, this integration significantly enhances the detection performance for small targets. Finally, the Focaler-PIoUv2 loss function is designed to replace the CIoU in the baseline algorithm. This replacement allows the algorithm to better balance hard and easy samples and improve detection accuracy. Experimental results on the public dataset VisDrone2019 show that MFRA-YOLO achieves superior accuracy-efficiency tradeoffs compared to the baseline YOLOv8n and other YOLO variants. Compared to YOLOv8n, MFRA-YOLO improves mAP50 by 3.5% and mAP50:95 by 2.3%, respectively. These performance gains are accompanied by only modest increases in parameter count and computational cost. Notably, while maintaining performance at 143 FPS, thereby satisfying the real-time deployment requirements for UAVs. Furthermore, compared with several state-of-the-art algorithms designed for UAV scenarios, MFRA-YOLO also offers distinct advantages. To verify the generalization ability and stability of MFRA-YOLO, comparative experiments are carried out on the RSOD dataset, where our algorithm consistently demonstrates excellent detection performance. Overall, these results confirm that MFRA-YOLO not only improves the detection performance for UAV imagery substantially but also achieves an excellent balance between detection accuracy and efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of object detection and UAV technologies, UAV image object detection has been increasingly applied across multiple domains. Compared with conventional object detection methods, UAV image object detection not only requires high detection accuracy, but also requires lightweight deployment and real-time processing capabilities, which have significant application value in disaster rescue1, environmental monitoring2, and traffic surveillance3. Compared to two-stage detection algorithms, one-stage algorithms (e.g., YOLO series4,5,6,7,8,9 and SSD10 eliminate the need for region proposal generation by directly performing classification and localization through anchor boxes. Although this approach sacrifices some detection accuracy, it achieves faster inference speed and lower computational demands, thereby better satisfying the real-time requirements of UAV image object detection.

However, UAV image object detection faces challenges unique to aerial imagery scenarios, with three key issues requiring particular attention. First, extreme scale variations are ubiquitous: targets within a single UAV frame span from minute distant objects to large nearby objects. Small objects often fail in feature extraction due to insufficient pixel density, while large targets may fail in feature extraction due to incomplete feature coverage. Second, densely clustered small objects consistently pose bottlenecks, particularly in scenarios like crowd monitoring, traffic surveillance, and crop detection. Such targets often cluster tightly, causing severe occlusion and feature blurring. Their limited pixel size further risks weak target signals being overwhelmed by complex backgrounds, increasing the likelihood of missed or false detections. Finally, real-time processing capability is critical for most UAV-based applications. Whether rapidly locating trapped individuals in emergency search-and-rescue operations, issuing risk alerts during dynamic threat detection, or enabling environmental awareness for autonomous navigation, low-latency detection results are essential for decision support. Therefore, balancing detection efficiency with accuracy remains the core trade-off for improving such technologies.

For the challenges of object detection in UAV images, researchers have proposed various innovative solutions. Wang et al.11 developed an enhanced feature extraction method based on FasterNet, which integrates shallow and deep features to minimize small target omission. However, this method relies on simple feature concatenation, resulting in insufficient interaction between cross-scale features and failure to fully exploit the correlation between shallow detailed information and deep semantic information. Wang et al.12 introduced an efficient multi-scale attention mechanism into the C2f structure of YOLOv8, explicitly addressing scale variations through cross-level feature enhancement. Qing et al.13 redesigned the RepVGG to construct RepVGG-YOLO, where the improved backbone network aggregates multi-scale features through parallel structural reparameterization. While this strengthens hierarchical representation, the fixed reparameterization structure lacks adaptability to dynamic scale variations in UAV images, and the computational cost increases linearly with the number of parallel branches. All of the above studies have enhanced shallow feature extraction through multi-scale feature fusion, thereby effectively reducing the miss detection rate of small targets, but they either suffer from inadequate cross-scale interaction or excessive computational overhead that conflicts with UAVs’ real-time deployment needs.

To address the challenges posed by high-density distributions of small targets in UAV imagery, researchers have put forward several key improvements. Zhang et al.14 enhanced YOLOv8 by integrating the RepVGG and PAFPN, supplemented with a dedicated small-target detection layer, achieving improved accuracy for densely distributed small objects. Nevertheless, the introduction of an additional detection layer significantly increases the number of parameters and computational complexity, making it difficult to meet the real-time requirements of UAV on-board deployment. Meng et al.15 improved the accuracy of small target detection by combining multi-scale attention mechanisms and deep convolution to aggregate local information, but their method overemphasizes local features while ignoring the global contextual relationships between dense small targets, leading to increased false positive rates in cluttered scenes. Lai et al.16 modified YOLOv5 through reduced downsampling ratios and additional detection layers to mitigate information loss during downsampling. They further introduced an enhanced feature extraction module to expand the receptive field, enhancing contextual feature extraction. Although this preserves more small-target details, the reduced downsampling ratio leads to a sharp increase in feature map size, which drastically raises computational cost and hinders real-time inference. The above researches have enhanced small-target detection accuracy through the introduction of dedicated small-target detection layers. However, they simultaneously lead to a significant increase in both computational complexity and parameter count, posing challenges to the real-time requirements of the detection algorithm.

To address the challenges posed by complex backgrounds in UAV image analysis, researchers have employed attention-driven strategies. Jiang et al.17 redesigned CenterNet by replacing its backbone with ResNet50 and incorporating channel-spatial attention mechanisms. This modification enables selective focus on salient regions, significantly improving small target detection amidst cluttered backgrounds. However, the ResNet50 backbone is relatively heavy, leading to high computational latency that is incompatible with UAV real-time tasks. Liu et al.18 proposed an enhanced YOLOv5 algorithm, which synergizes coordinate attention mechanism with hybrid dilated convolutional residuals. This dual enhancement strengthens both local feature discrimination and receptive field adaptability, particularly effective for targets obscured by intricate backgrounds. Yet, hybrid dilated convolutions exhibit sparse sampling of small targets due to their high dilation rates, thereby reducing the localization accuracy of small objects in complex backgrounds. Cao et al.19 integrated Swin Transformer with CSPDarknet53, leveraging global context preservation through self-attention mechanism. They further embedded coordinate attention into the neck network to enhance spatial-aware feature refinement for small objects in remote sensing imagery. However, the self-attention operation in Swin Transformer has a quadratic computational complexity relative to the input size, making it difficult to balance global context capture and computational efficiency. In response to diverse application scenarios, the above studies incorporated appropriate attention mechanisms, enabling algorithms to selectively focus on salient regions within feature maps. This adaptation significantly improves detection accuracy by enhancing feature discriminability, but they either suffer from high computational cost or inadequate balance between local and global features.

Additionally, research on object detection in UAV imagery has made significant strides in balancing efficiency and performance. Shen et al.20 proposed an anchor-free lightweight UAV object detection algorithm that leverages channel stacking to enhance feature extraction capabilities in lightweight networks. They further incorporated an attention mechanism to improve the algorithm’s ability to focus on relevant features. Xiao et al.21 integrated dynamic convolutions and ghost modules to achieve a more lightweight network architecture while enhancing feature extraction. Furthermore, they fused multi-scale ghost convolution with multi-scale generalized feature pyramid network to strengthen feature fusion capabilities. Inspired by eagle vision, Wang et al.22 combined the YOLOv5 detection framework with super-resolution networks and image reconstruction techniques. They proposed an adaptive feature fusion method to dynamically integrate multi-scale features: during training, super-resolution networks enhance small target details, while the super-resolution module is omitted during inference to balance real-time performance. Xiao et al.23 restructured the C3k2 module using the efficient convolution module to enhance multi-scale feature extraction. Additionally, a spatial bidirectional attention module was introduced to achieve mutual fusion of semantic and detail information. This module effectively suppresses the interference from complex backgrounds, enabling the network to focus on small objects in images.

Although the previous challenges in UAV-based image object detection have been alleviated, most existing approaches still compromise substantial computational resources in exchange for detection accuracy. In this study, built upon the YOLOv8 algorithm, we propose an improved algorithm combining Multi-scale Feature fusion and Receptive-field Attention-based convolution (MFRA-YOLO for short). The main contributions and innovations are as follows:

-

(1)

By integrating Monte Carlo attention into Receptive-field Attention-based convolution, we propose MCRAConv, a novel downsampling convolution module that replaces its counterpart in the baseline algorithm. Targeting the gap of insufficient cross-scale interaction and high computational cost in existing methods, MCRAConv enhances inter-channel local information interaction and mitigates target information loss during downsampling, thereby preserving feature richness while improving discriminability with negligible computational overhead.

-

(2)

A Multi-scale Selective Fusion (MSF) module and a Scale Sequence Feature Fusion (SSFF) module are integrated to form a novel module, MSSFF for short, which is then embedded into the feature fusion network. Addressing the gap of excessive computational cost in small-target detection, this integration enables MSSFF to effectively fuse multi-scale features without additional detection layers, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s detection performance for small targets by improving the consistency of feature representation across scales.

-

(3)

Focaler-IoU is introduced on the basis of Powerful-IoUv2, and Focaler-PIoUv2 is developed to replace the CIoU loss function. To tackle the imbalance of hard and easy samples in complex backgrounds, this loss function better solves the problem of sample imbalance, accelerates the convergence speed and improves the detection accuracy without increasing computational burden.

The synergistic effect of the above innovations is not only reflected in the design logic but also verified by quantitative experimental results on benchmark datasets. Compared with the baseline algorithm, our MFRA-YOLO yields a 3.5% improvement in mAP50 and a 2.3% gain in mAP50:95 on the public VisDrone2019 dataset, while maintaining a frame rate of 143 FPS. This performance gain not only substantially enhances detection accuracy but also fully satisfies the real-time demands of UAV image object detection, thus clearly validating the advanced performance and high efficiency of our proposed algorithm.

The subsequent sections will elaborate as follows: Sect. 2 introduces the architecture of the baseline algorithm. Section 3 details the improvements of the proposed algorithm, including the convolution module integrating receptive-field attention-based convolution and multi-scale attention, the neck network incorporating a multi-scale feature fusion strategy, and the novel Focaler-PIoUv2 loss function. Section 4 first establishes the experimental setup, encompassing hardware configurations and hyperparameter tuning. It then presents ablation and comparative experiments on both the VisDrone2019 and RSOD datasets to validate the effectiveness of each component and the generalization capability of the proposed algorithm. Finally, the experimental results are analyzed, and visualized detection results are provided. Section 5 summarizes the key contributions and limitations of this work, while outlining promising directions for future research.

Baseline algorithm

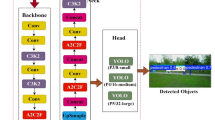

The YOLOv8 algorithm, a state-of-the-art framework introduced by Ultralytics in 2023, has an architecture as shown in Fig. 1. YOLOv8 offers five model variants, with their sizes ascending as n, s, m, l, and x. Considering the requirements for real-time in UAV image object detection tasks, this study selected YOLOv8n as the baseline algorithm, which comprises three main components: Backbone, Neck, and Head.

In the Backbone network, the C2f module is introduced to replace the CSP block. It employs five downsampling layers to hierarchically extract feature information at different scales. As described in detail in Fig. 1, C2f incorporates a residual structure with a gradient shunting connection, which facilitates more effective gradient propagation and feature representation. Second, the complete downsampling convolution operation comprises a 3 × 3 2D convolution, batch normalization, and a SiLU activation function. This systematic design stabilizes the downsampling process, thereby significantly improving the algorithm’s detection performance. Finally, the backbone includes the SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast) module. This converts feature maps into fixed-size representations through pooling operations, followed by concatenation and convolution to capture multi-scale features, which enhances detection performance while reducing computational complexity.

In the Neck network, FPN (Feature Pyramid Network)24 and PANet (Path Aggregation Network)25 are utilized to enhance feature fusion and representation. They employ top-down and bottom-up pathways, respectively, to integrate shallow and deep features.

The detection head of YOLOv8 adopts a decoupled structure, performing classification and bounding box regression tasks through two separate branches. For classification, BCE loss is used, while the bounding box regression task employs a combination of DFL and CIoU losses.

Although the YOLOv8 algorithm has achieved relatively good performance in object detection, particularly for small targets, it does not address the issue of parameter sharing in the downsampling convolution process. This oversight leads to incomplete utilization of the image’s feature information. Additionally, during feature fusion, the detailed information in high-resolution feature maps is overlooked, and the correlations among feature maps are not effectively exploited.

Proposed algorithm

In this study, we propose an improved algorithm that combines a novel downsampling and multi-scale sequence feature fusion. Its architecture is shown in Fig. 2.

First, this study designs a novel MCRAConv module for downsampling operation. MCRAConv dynamically generates receptive field spatial features based on different convolutional kernel sizes to address the issue of convolutional kernel parameter sharing, thereby emphasizing the importance of each feature within the receptive field space. Additionally, MCRAConv generates scale-variant attention maps through adaptive pooling operations, which enhances cross-scale feature map correlations and reduces the algorithm’s computational complexity.

Second, this study introduces the MSF module, which enables effective capture of contextual information from multi-scale feature maps and their comprehensive fusion. Furthermore, the MSF module is integrated with the SSFF module, allowing the algorithm to better leverage the correlations between multi-scale feature maps and thereby improve the detection accuracy for small targets.

Finally, this study proposes a novel Focaler-PIoUv2 loss function, which is composed of Focaler-IoU and Powerful-IoUv2. Designed to improve the algorithm’s detection accuracy and accelerate its convergence, this loss function replaces the CIoU loss function in the baseline algorithm.

Downsampling module integrating receptive-field attention-based convolution and multi-scale attention

Most existing downsampling methods rely heavily on convolutional operations. While convolutional operations expand the receptive field of images and reduce computational load, they suffer from parameter sharing limitations that result in inefficient utilization of image features. For UAV images characterized by large target scale differences and densely distributed small objects, we propose the MCRAConv module, which integrates Monte Carlo attention (MCA)26 with receptive-field attention-based convolutions27. The architecture of this module is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Most existing convolutional operations adopt fixed-parameter sliding windows for feature extraction, leading to partial feature overlap across distinct receptive fields for a given kernel. However, objects at different image locations exhibit significant variations in shape, color, and distribution. Shared parameters are unable to capture such variations, resulting in low feature utilization during the extraction process. Receptive-field attention-based convolutions address this issue by aggregating convolutional kernels of varying sizes and adjusting channel counts and spatial dimensions. This maps the input image to new receptive field features, comprehensively considering the importance of each feature within the receptive field. Taking a 3 × 3 convolutional kernel as an example: the C×H×W input feature map is expanded 9-fold along the channel dimension and then resized to a spatial dimension of C×3H×3W. Specifically, group convolutions are first employed to extract spatial features within the receptive field, thereby preserving channel-specific feature characteristics. The extracted features are then redistributed, mapping the original features to a new receptive field space to ensure feature independence in subsequent computations.

Given the abundance of small targets and substantial scale variations in UAV imagery, most existing algorithms demonstrate inadequate detection performance. Furthermore, while receptive-field convolutions expand the original receptive field, they also increase the distance to the contextual information surrounding targets. Traditional attention mechanisms (e.g., Squeeze-and-Excitation, SE) focus exclusively on channel-wise dependencies while overlooking spatial and scale variations. To address this limitation, we incorporate the MCA into receptive-field attention-based convolutions. By randomly selecting one of three pooling layers with distinct scales (1 × 1, 2 × 2, and 3 × 3 in this study) via a random seed to downsample the input feature map, we overcome the constraints of conventional fixed-scale pooling. Specifically, the 1 × 1 pooling layer captures global channel-wise dependencies to acquire contextual information surrounding the target, while the 2 × 2 and 3 × 3 pooling layers preserve local spatial details to enhance small target detection. Combining these three pooling strategies effectively mitigates the challenge of significant target scale variations in UAV imagery.

Subsequently, an attention map is generated via the Sigmoid activation function. This map is then element-wise multiplied with the features from the expanded receptive field, strengthening the algorithm’s focus on small objects and those with substantial scale variations. Randomly selecting different pooling scales through random seeds balances the algorithm’s dependence on both local and global information. If the input image is denoted as Fi, the feature map generated by the MCA module is computed as shown in Eq. (1):

where Fo denotes the output size of the feature map and \(\:\text{f}\text{}\text{(}{\text{F}}_{\text{i}\text{}}\text{,}{\text{F}}_{\text{o}}\text{)}\) denotes the average pooling function; \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{r}}\text{(}{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}\text{,}{\text{F}}_{\text{o}}\text{)}\) is the association probability. To guarantee a rational distribution of scale weights, \(\:{\text{P}}_{\text{r}}\text{(}{\text{F}}_{\text{i}}\text{,}{\text{F}}_{\text{o}}\text{)}\) must satisfy condition \(\:\sum\:_{\text{}\text{i}\text{=}\text{1}}^{\text{}\text{n}}{\text{P}}_{\text{r}}\left({\text{F}}_{\text{i}\text{}}\text{,\:}{\text{F}}_{\text{o}}\right)\text{=1}\). Meanwhile, condition \(\:\prod\:_{\text{}\text{i}\text{=}\text{1}}^{\text{}\text{n}}{\text{P}}_{\text{r}}\left({\text{F}}_{\text{i}\text{}}\text{,\:}{\text{F}}_{\text{o}}\right)\text{=0}\) ensures that only one scale is selected, thus mitigating feature confusion.

Finally, feature extraction is implemented via a k×k convolution operation with a stride = k, which ensures that the importance of each feature is maintained throughout the feature extraction workflow.

Neck network incorporating multi-scale feature fusion modules

The overall structure of the MSSFF incorporates a feature pyramid and a path aggregation architecture. Features from the backbone network are first fused across scales by the multi-scale selective fusion module28, whose activation function adjusts the weights of critical image information to enhance the algorithm’s focus on effective image features, thereby alleviating the problem of low detection accuracy caused by significant target scale variations. The scale sequence feature fusion module29 then combines the detailed spatial information in shallow feature maps with the semantic information in deep feature maps of the backbone network, constructing new feature maps that prioritize shallow-level details to improve small-target detection accuracy.

Specifically, the MSF module selectively fuses the features of P2, P3, P4, and P5 in Fig. 2. The SSFF module then performs cross-scale feature fusion for P3, P4, and P5, summing the results with the feature maps generated by the MSF module to obtain 80 × 80 feature maps optimized for small-target detection. Following the FPN-PANet structure, the remaining feature maps suitable for medium-sized and large-sized targets are generated in sizes of 40 × 40 and 20 × 20, respectively.

Multi-scale selective fusion module

The original algorithm’s feature pyramid structure only performs upsampling on small-scale feature maps and splices them with features extracted from the previous layer in the backbone network, but it ignores the more detailed information contained in large-scale feature maps. This oversight makes the algorithm less effective in detecting small targets in UAV images. To address this, this study introduces a multi-scale selective feature fusion module, which fuses features from large, medium, and small scales. This allows for a full combination of the richer detailed information in shallow feature maps with the high-level semantic information in deep feature maps, thereby improving the algorithm’s detection accuracy for small targets. The structure of the multi-scale selective fusion module is shown in Fig. 4.

Before feature fusion in the MSF module, it is necessary to adjust the channel dimensions and spatial sizes of feature maps by performing down-sampling on large-size features and upsampling on small-size features. This ensures that feature maps have identical spatial dimensions and channel counts. These aligned feature maps are then subjected to global average pooling to compute channel-wise average weights, followed by splicing along the height dimension to form new feature maps. The weights are subsequently normalized between 0 and 1 using the Sigmoid activation function. Next, channel-wise weights at the same spatial positions are further normalized via the Softmax function to emphasize critical information within the multi-scale averaged weights. Finally, the normalized weights are element-wise multiplied with their corresponding features, and the weighted features are summed to generate the fused output features.

Scale sequence feature fusion module

The traditional feature pyramid structure employed in the neck network of YOLOv8 simply fuses pyramid features by concatenating them along the channel dimension, failing to effectively utilize the correlations among all pyramid feature maps. Aiming at the challenges of significant target scale variations and dense small-target distributions in UAV images, this study introduces the SSFF module. Taking large-scale feature maps as the foundation, the module fuses multi-scale features while prioritizing the detailed information in shallow feature maps. This design addresses the algorithm’s issues of missed detections and false positives for small targets, significantly enhancing the information interaction among its multi-scale feature maps. The structure of the scale sequence feature fusion module is shown in Fig. 5.

The SSFF module takes the P3 feature map as its base. Prior to upsampling, the channel dimensions of P3, P4, and P5 feature maps are first unified using 1 × 1 convolutions. P4 and P5 are then upsampled to the resolution of P3 via nearest-neighbor interpolation, as the high-resolution P3 map contains richer detailed information about small targets. Next, an unsqueeze operation converts the 3D feature maps (Channel, Width, Height) into 4D tensors (Depth, Channel, Width, Height), which are concatenated along the depth dimension. Finally, scale sequence features are extracted using 3D convolutions, followed by 3D pooling to reduce the dimensionality and generate the fused 3D feature maps.

Loss function combining powful-IOUV2 and focaler-IOU

The bounding box regression loss function enhances target localization by optimizing the discrepancies between predicted and ground-truth box parameters, playing a crucial role in object detection tasks. The IoU-based loss function calculates the intersection over union (IoU) of the predicted and ground-truth boxes, which measures their overlap, aiming to achieve accurate target localization. However, when the predicted boxes and ground-truth boxes do not overlap, the performance of IoU-based loss functions degrades significantly. To address this, numerous improved IoU variants have been proposed in recent years. YOLOv8 employs the CIoU loss, which incorporates the distance between box centers and aspect ratio differences, thereby enhancing the algorithm’s target localization capability. The formula for CIoU is shown in Eq. (2):

where \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{Intersection}}\text{}\)and \(\:{\text{S}}_{\text{Union}}\:\)denote the intersection and union between predicted and ground-truth boxes, respectively; d is the distance between the centroid of the predicted boxes and the ground-truth boxes; \(\:c\) is the length of the diagonals of the minimum enclosing rectangle, as shown in Fig. 6. \(\:\alpha\:\) is the weight factor, \(\:\nu\:\) is the parameter used to measure the similarity of aspect ratios, and wg, hg, wp, and hp are the widths and heights of the ground-truth and predicted boxes, respectively.

The CIoU loss function also exhibits the following shortcomings: (1) CIoU fails to address the imbalance between easy and hard samples in object detection. When samples of one type (easy or hard) vastly outnumber those of the other, the loss generated by the dominant sample type will dominate the total loss, leading to insufficient learning of the minority sample type. (2) Although CIoU incorporates the aspect ratio as a penalty term in its loss function, it cannot effectively distinguish the actual geometric differences between predicted boxes and ground truth boxes when the width and height of the two are swapped while the aspect ratio remains unchanged. To address these limitations, this study proposes a novel loss function, Focaler-PIoUv2, which synergistically integrates the strengths of Powerful-IoUv230 and Focaler-IoU31.

To tackle the imbalance between easy and hard samples in detection tasks, Focaler-IoU reconstructs the IoU loss via linear region mapping and dynamically assigns weights to hard samples. This design prioritizes attention to hard cases (e.g., occluded objects, small targets, and targets in low-light environments), preventing easy samples from dominating the loss calculation. Consequently, it resolves CIoU’s limitation of insufficient learning for a small number of hard samples. To overcome CIoU’s focus on aspect ratios while ignoring the explicit width and height of boxes, Powerful-IoUv2 introduces an adaptive penalty factor based on the dimensions of ground truth boxes. Unlike CIoU, which relies on aspect ratios, Powerful-IoUv2 calculates this penalty factor using the explicit width and height values of ground truth boxes, enabling it to effectively distinguish scenarios where predicted boxes and ground truth boxes swap width and height while maintaining the same aspect ratio. Additionally, by integrating a gradient adjustment function based on anchor quality, Powerful-IoUv2 guides anchor boxes to regress toward ground truth boxes along a more direct path. This avoids excessive expansion of anchor box areas and thereby accelerates algorithm convergence.

Most existing bounding box regression loss functions, due to their penalty factor design strategies, lead to excessive expansion of the bounding box area during regression. Furthermore, this area growth slows down convergence, and CIoU is no exception. To address this, this study adopts PIoUv2 to replace CIoU as the loss function. PIoU introduces an adaptive target-size penalty factor β to solve the issue of bounding box area expansion, with its calculation detailed in Eq. (6):

where dw1, dw2, dh1, dh2 are the absolute values of the distances between the predicted bounding boxes and the ground-truth bounding boxes; wgt and hgt are the width and height of the ground-truth boxes.

Using β as the penalty factor prevents the bounding boxes from expanding in size during regression. This is because the denominator of β depends solely on the size of the ground-truth boxes, rather than the smallest enclosing bounding boxes of the ground-truth and predicted boxes. By combining penalty factor β with a gradient-adjusting function that leverages anchor-box quality, PIoU is derived. This allows anchor boxes to converge toward ground-truth boxes along a more direct path during bounding box regression, avoiding area expansion and accelerating convergence. The formulation is presented in Eq. (7):

A nonmonotonic attention layer governed by a single hyperparameter is subsequently integrated into PIoU, yielding PIoUv2. This enhancement improves the algorithm’s capability to focus on medium-to-high-quality anchor boxes. The formulation for PIoUv2 is presented in Eq. (8):

where \(\:u\left(\lambda\:q\right)\) denotes the attention function, and \(\:q\) is employed instead of the penalty factor β. When \(\:q=1\), β = 0, implying that the ground-truth bounding boxes fully overlaps completely with the anchor boxes. In the function, \(\:q\) decreases as β keeps increasing, representing a gradual decrease in the overall anchor box mass. \(\:\lambda\:\) is the hyperparameter that controls the attention function.

In object detection tasks, the imbalance between hard and easy samples significantly impacts the algorithm’s detection accuracy. From the perspective of target scale, common detection targets in images are typically classified as easy samples, while extremely small targets are regarded as hard samples due to the challenge of accurate localization. For object detection tasks with a high proportion of easy samples, the algorithm should prioritize easy samples during the bounding box regression process to enhance detection performance. By contrast, in tasks where hard samples dominate, the algorithm needs to focus on hard samples during the bounding box regression process.

Given the dense distribution of small targets in UAV images, UAV image object detection can be characterized as a task with a high proportion of hard samples. Therefore, this study introduces the Focaler-IoU loss function into the bounding box regression loss function, reconstructing the IoU loss through linear interval mapping. The computational formula is presented in Eq. (11):

where \(\:{IoU}^{focaler}\) is the reconstructed Focaler-IoU, \(\:\left[d,u\right]\in\:\left[\text{0,1}\right]\), The bounding box regression loss function can be made to focus on different regression samples by adjusting the values of \(\:d\) and \(\:u\) in formulas.

The Focaler-IoU and PIoUv2 will be combined to obtain a new bounding box regression loss function, Focaler-PIoUv2, with the formula is presented in Eq. (13):

To verify the effectiveness of the improved loss function, we conduct comparative experiments among our proposed Focaler-PIoUv2, CIoU (the baseline loss function), and other mainstream loss function alternatives. The experimental results are presented in Table 1. As indicated in the table, Focaler-PIoUv2 consistently delivers superior average detection accuracy compared to both CIoU and the other mainstream loss functions (e.g., MPDIoU and SIoU).

Experiments and discussion

This section first presents the experimental environment and training strategy, then describes the datasets employed in the experiments, followed by an introduction to the evaluation metrics for the algorithm, and finally reports the experimental results along with their analysis.

Environment of the experiment

The parameters of the experimental environment are presented in Table 2.

The number of experimental training epochs is set to 300. the input image size is set to 640 × 640, the number of random seeds is set to 0, and batch size is set to 16, respectively, as a way to ensure efficient memory utilization and training stability. The initial learning rate is set to 0.01, and the final learning rate is one hundredth of that. Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) is chosen as the optimizer with a momentum of 0.937. A weight decay of 0.0005 is also applied to prevent overfitting and enhance algorithm’s generalization ability.

Datasets

The datasets employed in this study are the public datasets VisDrone201932 and RSOD33. VisDrone2019 stands as one of the prominent UAV-based image datasets for contemporary computer vision tasks. Jointly collected by the Machine Learning and Data Mining Laboratory of Tianjin University and the ASKYEYE Data Mining Team, the dataset was acquired using various types of UAVs across 14 cities in China, encompassing diverse geographical and environmental scenarios. Specifically, it covers both urban and rural settings, which exhibit distinct characteristics: urban environments are characterized by dense buildings, crowded traffic, and complex man-made structures, leading to high target density and overlapping objects; in contrast, rural environments feature sparse settlements, open natural landscapes, and relatively scattered targets with simpler background interference. Data collection was conducted across multiple seasons and diverse weather conditions (e.g., sunny, cloudy and foggy), with lighting conditions ranging from bright daytime to low-light nighttime environments. The dataset comprises 288 video clips and 10,209 static images.

VisDrone2019 encompasses 10 target categories: People, Bicycle, Car, Van, Awning-Tricycle, Truck, Pedestrian, Tricycle, Bus, and Motor. Its key distinguishing features are significant target scale variation and dense small-target distribution, which render it particularly well-suited for evaluating algorithm improvements in small-target object detection tasks relative to other computer vision datasets.

Figure 7 presents the label information of the VisDrone2019 dataset. Specifically, it illustrates the label types, quantities, and distribution characteristics of the dataset. Following the order from left to right and top to bottom: The first subfigure shows the category distribution of object instances, revealing that vehicles and pedestrians predominate. The second subfigure presents the distribution of bounding box dimensions, confirming the prevalence of small targets and notable variations in target scales. The third subfigure presents the spatial distribution of bounding box centers, indicating that they are primarily concentrated in the central and lower regions of the image. The fourth subfigure illustrates the aspect ratio distribution relative to image dimensions, demonstrating higher object density in the lower-left quadrant, further confirming that the dataset contains abundant small targets.

To further validate the robustness and generalization ability of the proposed algorithm, experiments comparing the proposed method with other algorithms are conducted using the RSOD dataset. Unlike VisDrone2019, RSOD is typically used for remote sensing image object detection and contains 4,993 aircraft, 1,586 oil tanks, 180 overpasses, and 191 playgrounds. The data was acquired via satellite remote sensing and high-altitude UAVs under predominantly sunny and cloudy weather conditions, with minimal precipitation to ensure image clarity. This dataset also exhibits substantial target scale variation and a dense distribution of small targets, complementing VisDrone2019 by covering more large-scale and remote sensing-specific scenarios.

Evaluation metrics

To evaluate the algorithm’s detection performance, this study employs several evaluation metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), and Mean Average Precision (mAP). The formulas for these metrics are presented in this section:

Precision

Precision is defined as the ratio of true positive samples to the total number of predicted positive samples, and its calculation is provided in Eq. (14):

here, TP (True Positive) denotes that the algorithm predicts a sample as positive and the sample is actually positive; FP (False Positive) denotes that the algorithm predicts a sample as positive while the sample is actually negative.

Recall

Recall is defined as the ratio of true positive samples to the total number of actual positive samples, and its calculation is provided in Eq. (15):

where FN (False Negative) denotes that the algorithm predicts a sample as negative while the actual label is positive.

Mean average precision

mAP is defined as the average of the AP (Average Precision) values across all categories, which measures the algorithm’s overall detection performance across all classes. Its calculation is provided in Eq. (16):

where \(\:A{P}_{i}\) denotes the AP value with category index value i, and N denotes the number of categories of samples in the training dataset. mAP50 denotes the average accuracy when the IoU of the detection algorithm is set to 0.5, and mAP50:95 denotes the average accuracy when the IoU of the detection algorithm is set from 0.5 to 0.95.

In practical deployment, object detection tasks require not only high accuracy but also explicitly evaluating computational cost, parameter count, and inference speed. Computational cost is typically measured in floating-point operations (FLOPs), parameter count in total parameters (Params), and inference speed in frames per second (FPS).

Results and analysis of the experiment

Ablation experiments on the VisDrone2019 dataset

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm improvements, this study applies MCRAConv, Focaler-PIoUv2, MSSFF, and their combinations to the baseline algorithm for ablation experiments on the validation set.

As shown in Table 3, algorithm A denotes the baseline algorithm YOLOv8n. Algorithms B, C, and D respectively denote the variants with the individual introduction of MCRAConv, MSSFF, and Focaler-PIoUv2. Algorithm E incorporates both MCRAConv and MSSFF. Algorithm F integrates MCRAConv with Focaler-PIoUv2. Algorithm G combines MSSFF and Focaler-PIoUv2.

In the validation set, Algorithm B outperforms the baseline by achieving 1.1% and 0.6% improvements in mAP50 and mAP50:95, respectively. This demonstrates that MCRAConv can more effectively leverage convolution kernel parameters via receptive field attention. Notably, by introducing random feature map sampling, the algorithm incurs negligible increases in computational cost. Algorithm C achieves more significant improvements of 1.6% and 1.0% in the above metrics, verifying that the MSSFF module effectively fuses multi-scale feature information to enhance detection accuracy. Although Algorithm C inevitably increases in computational load and parameter count, it still satisfies real-time inference requirements. Algorithm D obtains 0.6% and 0.2% gains in mAP50 and mAP50:95, respectively, indicating that Focaler-PIoUv2 effectively balances hard and easy samples while suppressing bounding box expansion during regression. Importantly, this loss function introduces no additional computational overhead or parameters, thus preserving the algorithm’s real-time performance. Algorithms E, F, and G demonstrate improvements of 3%, 1.8%, and 1.6% in mAP50, and 1.8%, 1.1%, and 1.2% in mAP50:95, respectively. Finally, the proposed algorithm outperforms the baseline algorithm A by 3.5% in mAP50, and 2.3% in mAP50:95, while still satisfying the requirements for real-time detection.

After validating the effectiveness of algorithm improvements on the validation set, this study further evaluates the model’s generalization ability via ablation experiments on the test set. As shown in Table 4, MFRA-YOLO outperforms the baseline by 3.6% in mAP50 and 2.1% in mAP50:95, confirming the proposed algorithm’s generalization capability and overall effectiveness. Additionally, by comparing the mAP50, mAP50:95, and PR curves shown in Fig. 8, it is evident that the performance of the proposed algorithm surpasses that of the baseline algorithm.

Experimental comparison with other classic algorithms

To validate the MFRA-YOLO’s detection performance for each category, this study evaluates it against the baseline on a category-by-category basis using two metrics mAP50 and mAP50:95 on the datasets of VisDrone2019 and RSOD, respectively.

As demonstrated in Table 5, MFRA-YOLO achieves more substantial improvements in per-category detection accuracy on the VisDrone2019 dataset compared to the baseline algorithm. On the validation set, the most significant improvements in mAP50 are observed in the Truck and Tricycle categories, with both achieving a 4.2% enhancement. For the mAP50:95 metric, the most significant improvement (3.2%) is observed in the Bus category. Notable enhancements are also evident in detecting Pedestrian, People, and Motor, with mAP50 improvements of 3.7%, 3.4%, and 3.4% respectively. On the test set, the Bus category exhibits the highest accuracy improvement, with mAP50 and mAP50:95 increasing by 5.3% and 4.5% respectively.

Similarly, Table 6 shows that the proposed algorithm delivers pronounced improvements on the RSOD dataset, particularly in the Overpass category, which achieves a more than 20% gain in mAP50 on the test set. These results indicate that the proposed algorithm effectively boosts detection accuracy for small targets and objects with large scale variations, enhancing overall detection performance. This further validates the algorithm’s effectiveness in remote sensing image object detection and its robust generalization capability.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm in this study, comparative experiments are conducted where the proposed algorithm is compared with algorithms from the YOLO series and other classic algorithms.

As presented in Table 7, various algorithms exhibit notable trade-offs between detection accuracy and inference efficiency, whereas our MFRA-YOLO achieves an excellent balance and thus demonstrates prominent overall performance advantages. In comparison with traditional object detection algorithms (e.g., SSD and Faster-RCNN), MFRA-YOLO delivers comprehensive superiority in detection performance. When benchmarked against the baseline YOLOv8n and other YOLO variants: YOLOv5n and YOLOv9t attain optimal results in FPS and parameter count, respectively, yet MFRA-YOLO showcases substantial advantages in detection accuracy; while the Transformer-based RT-DETR achieves the highest detection accuracy, its excessive parameter count, heavy computational load, and low frame rate render it incompatible with the real-time and resource-constrained requirements of UAV-based object detection. Furthermore, MFRA-YOLO achieves 37.1% mAP50 and 21.9% mAP50:95 with only a marginal increase in computational load and parameter count, while maintaining a frame rate of 143 FPS—sufficient to meet the demands of real-time UAV image target detection. Even when compared with state-of-the-art UAV-specific detection algorithms (UAV-YOLO and YOLO-RACE), MFRA-YOLO retains leading overall performance.

Similarly, comparative experiments are conducted on the RSOD dataset, with results detailed in Table 8. The results reveal that our MFRA-YOLO achieves 96.8% mAP50 and 67.4% mAP50:95, demonstrating a remarkable detection capability. When compared with all non-Transformer-based algorithms, MFRA-YOLO delivers comprehensive superiority in detection performance. Even against Transformer-based algorithms, its detection accuracy remains highly competitive. These findings further validate the effectiveness and robustness of our improved algorithm.

Visualization of detection results

To visually validate the effectiveness of the innovative modules in MFRA-YOLO, this study selects six representative UAV image scenarios, as illustrated in Fig. 9. From top to bottom, these scenarios are: scenes with significant target scale variations, dense target scenes, low-light night scenes, sparse target scenes in open areas, scenes with severe target occlusion, and scenes under strong illumination. A comparative visualization analysis is performed. Specifically: (a) denotes the original input image; (b) to (d) represent the detection outputs of YOLOv8n, YOLOv9, and YOLOv10, respectively; (e) denotes the detection results of MFRA-YOLO.

In scenes with significant target scale variations, the comparison results in the first row of Fig. 9 demonstrate that MFRA-YOLO effectively detects objects with large scale differences, whereas other comparative algorithms fail to identify such objects. This clearly illustrates that the MCRAConv module enhances the algorithm’s cross-scale correlation capability, while the integration of MSSFF further improves the network’s multi-scale feature fusion performance. In dense target scenes, the comparative results in the second row of Fig. 9 reveal that the baseline YOLOv8n algorithm fails to detect the motorcycle in the lower-left corner and suffers from severe missed detections among the numerous dense objects on the right. While other comparative algorithms successfully detect the lower-left motorcycle, they still exhibit varying degrees of missed detections for the dense small targets on the right. In contrast, MFRA-YOLO specifically optimizes small-object feature fusion through the SSFF module embedded in the MSSFF. Consequently, its detection performance for densely packed objects on the right is markedly superior to that of other comparative algorithms, as clearly illustrated in the figure.

In low-light night scenes and strong illumination environments, comparative algorithms exhibit misdetections and missed detections due to lighting interference. Particularly in low-light conditions, insufficient illumination complicates object contour extraction, leading to severe missed detections. The proposed MFRA-YOLO effectively alleviates such interference by strengthening detail extraction in low-light scenarios, thereby reducing missed detections significantly. In sparse target scenes in open areas, comparative algorithms perform poorly on edge-located objects (e.g., those in the upper-right corner of the image). In contrast, MFRA-YOLO achieves relatively comprehensive and accurate detection of these easily overlooked edge targets. In scenes with severe target occlusion, comparative algorithms show substantial missed detections for small objects (e.g., motorcycles) with severe mutual occlusion overhead, as clearly presented in the figure. Although MFRA-YOLO cannot perfectly detect all such occluded instances, it significantly mitigates this issue.

Overall, MFRA-YOLO consistently outperforms YOLOv8n, YOLOv9, and YOLOv10 across all six representative scenarios. This fully demonstrates that its innovative design effectively addresses the core challenges of UAV image object detection.

Conclusion and future work

In this study, we propose MFRA-YOLO, an object detection algorithm for UAV images that balances real-time detection requirements with improved small-target detection accuracy. First, addressing the challenge of complex backgrounds in UAV imagery, we propose the MCRAConv module. By enhancing cross-channel local information interaction, this module mitigates target information loss during downsampling and addresses the limitation of parameter sharing in convolutional kernels, thereby emphasizing the importance of each feature. Second, to handle the significant scale variations in UAV targets, we design a multi-scale selective feature fusion module combined with a scale sequence feature fusion mechanism. This enables effective integration of multi-scale features, fully fusing deep high-level semantic information with shallow low-level detailed information. Finally, we propose the Focaler-PIoUv2 loss function, which better addresses class imbalance between hard and easy samples, accelerates algorithm convergence, and boosts detection accuracy. Experimental results on the VisDrone2019 and RSOD datasets demonstrate that the proposed algorithm achieves substantial improvements across all evaluation metrics compared to the baseline, with only marginal increases in algorithm parameter count and computational cost. Comparative experiments with other algorithms show that MFRA-YOLO not only achieves higher detection accuracy but also meets the real-time requirements of UAV image object detection. Visualization results further confirm that the algorithm performs robustly across diverse UAV-captured scenarios, significantly reducing instances of missed or false detections.

Notably, while the algorithm’s computational complexity and parameter count have increased to varying degrees during the optimization process, these trade-offs are acknowledged as areas for future exploration.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Lei, T., Li, C. & He, X. Application of aerial remote sensing of pilotless aircraft to disaster emergency rescue. J. Nat. Disasters. 20 (1), 178–183 (2021).

Hu, Y., Jing, W., Yang, C. & Shu, S. Review of coastal ecological environment monitoring based on unmanned aerial vehicle remote sensing. Bull. Surveying Mapp. 1 (6), 18–24 (2022).

Byun, S., Shin, I. K., Moon, J., Kang, J. & Choi, S. I. Road traffic monitoring from UAV images using deep learning networks. Remote Sens. 13 (20), 4027 (2021).

Redmon, J., Divvala, S., Girshick, R. & Farhadi, A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 2016, 779–788 (2016).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: better, faster, stronger. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 2017, 6517–6525 (2017).

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An incremental improvement. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.02767 (2018).

Jocher, G. Ultralytics YOLOv5. https://github.com/ultralytics/YOLOv5/tree/v7.0 (2020).

Wang, C., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 7464–7475 (2023).

Jocher, G., Chaurasia, A. & Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLOv8. https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (2023).

Liu, W. et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. Comput. Vision—ECCV. 9905, 27–31 (2016).

Wang, G. et al. UAV-YOLOv8: a small-object-detection model based on improved YOLOv8 for UAVaerial photography scenarios. Sensors 23 (16), 7190 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. A remote sensing image target detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv8. Appl. Sci. 14 (4), 1557 (2024).

Qing, Y., Liu, W., Feng, L. & Gao, W. Improved YOLO network for free-angle remote sensing target detection. Remote Sens. 13 (11), 2171 (2021).

Zhang, Z. & Drone-YOLO An efficient neural network method for object detection in drone images. Drones 7 (8), 526 (2023).

Meng, X., Yuan, F. & Zhang, D. Improved model MASW YOLO for small target detection in UAV images based on YOLOv8. Sci. Rep. 15, 25027 (2025).

Lai, H., Chen, L., Liu, W., Yan, Z. & Ye, S. STC-YOLO: small object detection network for traffic signs in complex environments. Sensors 23 (11), 5307 (2023).

Jiang, X., Cui, Q. & Wang, C. A model for infrastructure detection along highways based on remote sensing images from UAVs. Sensors 23 (8), 3847 (2023).

Liu, Z., Gao, Y., Du, Q., Chen, M. & Lv, W. YOLO-extract: improved YOLOv5 for aircraft object detection in remote sensing images. IEEE Access. 11, 1742–1751 (2023).

Cao, X., Zhang, Y., Lang, S. & Gong, Y. Swin-transformer-based YOLOv5 for small-object detection in remote sensing images. Sensors 23 (7), 3634 (2023).

Shen, J. et al. An anchor-free lightweight deep convolutional network for vehicle detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (12), 24330–24342 (2022).

Xiao, L., Li, W., Yao, S., Liu, H. & Ren, D. High-precision and lightweight small-target detection algorithm for low-cost edge intelligence. Sci. Rep. 14, 23542 (2024).

Wang, D., Gao, Z., Fang, J., Li, Y. & Xu, Z. Improving UAV aerial imagery detection method via superresolution synergy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 18, 3959–3972 (2025).

Xiao, L. et al. EDet-YOLO: an efficient small object detection algorithm for aerial images. Real-Time Image Proc. 22, 175 (2025).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 2017, 2117–2125 (2017).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, vol. 8759–8768 (2018).

Dai, W. et al. Exploiting scale-variant attention for segmenting small medical objects. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.07720 (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. RFAConv: Innovating spatial attention and standard convolutional operation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03198 (2023).

Xie, L. et al. SHISRCNet: Super-resolution and classification network for low-resolution breast cancer histopathology image. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.14119v1 (2023).

Kang, M., Ting, C., Ting, F. & Phan, R. C. W. ASF-YOLO: A novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image Vis. Comput. 147, 105057 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. Powerful-IoU: more straightforward and faster bounding box regression loss with a nonmonotonic focusing mechanism. Neural Netw. 170, 276–284 (2024).

Zhang, H., Zhang, S. & Focaler-IoU More focused intersection over union loss. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.10525 (2024).

Zhu, P. et al. Detection and tracking Meet drones challenge. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 44 (11), 7380–7399 (2021).

Long, Y., Gong, Y., Xiao, Z. & Liu, Q. Accurate object localization in remote sensing images based on convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 44 (5), 2486–2498 (2017).

Ren, S. et al. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 39 (6), 1137–1149 (2017).

Zhao, Y. et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08069 (2023).

Li, C. et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.02976 (2022).

Wang, C., Yeh, I. H. & Liao, H. YOLOv9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. Comput. Vision—ECCV. 15089, 1–21 (2023).

Wang, A. et al. YOLOv10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.07465 (2024).

Wang, W., Wang, C., Wei, W., Tang, Y. & Zeng, B. A lightweight object detection algorithm for resource-constrained UAVs via multi-module optimization and channel pruning. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 37 (339), 1 (2025).

Bae, M. H., Park, S. W., Park, J., Jung, S. H. & Sim, C. B. YOLO-RACE: reassembly and convolutional block attention for enhanced dense object detection. Pattern Anal. Appl. 28 (90), 1 (2025).

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Jiangxi Provincial Department of Water Resources Science & Technology Program Foundation (Grant NO. 202325ZDKT17, 202426ZDKT13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Fang Dong, Binbin Gui and Wenfeng Wang; methodology, Fang Dong, Binbin Gui and Wenfeng Wang; software, Binbin Gui and Wenjie Fan; validation, Binbin Gui and Qihang Liu; formal analysis, Wenfeng Wang and Fang Dong; investigation, Qihang Liu; data curation, Qihang Liu; writing-original draft preparation, Fang Dong, Binbin Gui and Wenfeng Wang; writing-review and editing, Fang Dong, Binbin Gui and Wenfeng Wang; supervision, Wenfeng Wang; project administration, Fang Dong and Wenfeng Wang; funding acquisition, Wenfeng Wang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, F., Gui, B., Wang, W. et al. An improved UAV image object detection algorithm combining multi-scale feature fusion and receptive-field attention-based convolution. Sci Rep 16, 4579 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34711-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34711-y