Abstract

The rapid expansion of edge-cloud infrastructures and latency-sensitive Internet of Things (IoT) applications has intensified the challenge of intelligent task offloading in dynamic and resource-constrained environments. This paper presents an Adaptive and Intelligent Customized Deep Q-Network (AICDQN), a novel reinforcement learning-based framework for real-time, priority-aware task scheduling in mobile edge computing systems. The proposed model formulates task offloading as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and integrates a hybrid Gated Recurrent Unit-Long Short-Term Memory (GRU-LSTM) load prediction module to forecast workload fluctuations and task urgency trends. This foresight enables a Dynamic Dueling Double Deep Q-Network \((\text {D}^{4}\text {QN})\) agent to make informed offloading decisions across local, edge, and cloud tiers. The system models compute nodes using priority-aware M/M/1, M/M/c and M/M/\(\infty\) queuing systems, enabling delay-sensitive and queue-aware decision-making. A dynamic priority scoring function integrates task urgency, deadline proximity, and node-level queue saturation, ensuring real-time tasks are prioritized effectively. Furthermore, an energy-aware scheduling policy proactively transitions underutilized servers into low-power states without compromising performance. Extensive simulations demonstrate that AICDQN achieves up to 33.39% reduction in delay, 57.74% improvement in energy efficiency, and 81.25% reduction in task drop rate compared with existing offloading algorithms, including Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), Distributed Dynamic Task Offloading (DDTO-DRL), Potential Game based Offloading Algorithm (PGOA), and the User-Level Online Offloading Framework (ULOOF). These results validate AICDQN as a scalable and adaptive solution for next-generation edge-cloud systems requiring efficient, intelligent, and energy-constrained task offloading.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid proliferation of intelligent and latency-sensitive applications, such as augmented reality, autonomous vehicles, and real-time video analytics, has imposed stringent computational and latency requirements on mobile and IoT devices. These devices, often constrained by limited battery life, processing power, and memory, are unable to meet the real-time processing demands of modern workloads1. Although cloud servers offer strong computing capabilities, task offloading to the cloud incurs high transmission overhead and delays, especially under bandwidth constraints or network fluctuations, making cloud-only models unsuitable for real-time, delay-sensitive applications2.

To bridge this capability gap, Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) and edge-cloud collaborative architectures have emerged as promising paradigms that bring computational resources closer to the data source. By enabling computational offload of user equipment (UE) to nearby edge servers or remote cloud infrastructures, these architectures help reduce application latency and improve energy efficiency3. As illustrated in Fig. 1, this hierarchical architecture comprises three layers: the device layer, which includes user endpoints and IoT sensors; the edge layer, which handles local processing, caching and response; and the cloud layer, which is responsible for large-scale data analytics and storage. This structure supports distributed intelligence, allowing efficient and scalable computation throughout the network4.

Despite these advantages, task offloading in heterogeneous edge-cloud environments remains challenging due to dynamically changing workload patterns, network uncertainties, resource scarcity at the edge, and the diverse priority needs of tasks. Inefficient or static task allocation strategies can cause resource underutilization, increased latency, and higher energy consumption5. Moreover, unpredictable task arrivals and limited computational resources may lead to queue buildup, task failure, or deadline violations-especially for edge servers operating under constrained conditions6.

In addition to these challenges, existing studies such as7,8 consider simplified MEC settings where non-divisible tasks are processed without incorporating realistic queueing behavior at edge nodes. These approaches assume that each task must be processed within a single time slot, overlooking the fact that task execution frequently spans multiple slots due to varying load levels. Consequently, task delay can be significantly affected by previously queued jobs, especially in high traffic conditions. Furthermore, while7,8 primarily addresses delay-tolerant workloads, modern real-time applications require strict deadline guaranties, making such simplifications unsuitable for practical latency-critical MEC deployments. Another largely overlooked but critical aspect is priority sensitivity. In real-world scenarios, tasks exhibit varying urgency: real-time applications (e.g., emergency alerts, healthcare monitoring) demand strict deadlines, while delay-tolerant tasks (e.g., backups, updates) can tolerate longer wait times. Conventional resource allocation mechanisms and heuristic-based offloading approaches treat all tasks equally or apply static policies, resulting in degraded QoS for high-priority workloads under peak demand9.

These challenges require intelligent and adaptive task scheduling frameworks capable of responding to dynamic environmental changes while minimizing latency and energy consumption. In this context, DRL has gained significant attention for its ability to learn optimal offloading policies through continuous interaction with the environment10,11. Among DRL techniques, the Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) provides superior training stability by separating action selection from value evaluation, thus reducing the overestimation bias present in conventional DQN frameworks12.Furthermore, the Dueling Double Deep Q-Network (D3QN) introduces a separate advantage stream to evaluate the relative importance of actions, improving convergence efficiency and robustness of decision in dynamic environments13. However, many existing DRL-based solutions still lack integrated workload prediction, queue-aware decision-making, and energy-constrained optimization, limiting their deployment in real-time operational environments.

To address these limitations, we propose AICDQN (Adaptive and Intelligent Customized Deep Q-Network), a unified DRL-based framework for proactive, priority-aware, and energy-efficient task offloading in hierarchical edge-cloud systems. AICDQN employs a Dynamic Dueling Double Deep Q-Network (D4QN) to stabilize value estimation and enable robust learning under varying network conditions. A hybrid GRU–LSTM module forecasts the future system load, enabling anticipatory scheduling and queue regulation. Task offloading decisions are modeled as an MDP using M/M/1 queues for local devices, M/M/c for edge servers, and \(M/M/\infty\) for cloud computing to balance delay, energy consumption, and priority fulfillment. Additionally, an energy-aware policy regulates server activity for power savings without compromising Quality of Service (QoS).

The primary contributions are summarized as follows.

-

Priority-aware task offloading in heterogeneous edge-cloud environments: We formulate a realistic multi-tier MEC offloading model incorporating heterogeneous queueing delay, task urgency levels, and deadline constraints to jointly minimize latency, energy usage, and task drop rate.

-

AICDQN-based intelligent decision-making: A customized D4QN agent enhanced with GRU-LSTM workload prediction enables stable, foresight-driven, and resource-aware scheduling decisions based on local system observations such as task size, queue state, and predicted load.

-

Queue-aware MDP with energy constraints: We model system dynamics using queue theory and propose an energy-aware server state control strategy to activate, idle, or sleep servers according to forecasted workload.

-

Extensive simulation and comparative evaluation: Evaluating AICDQN against existing benchmark algorithms based on average task delay, task drop ratio, and energy consumption under varying workload conditions.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows. Section “Related works” provides a comprehensive review of related work in task offloading and deep reinforcement learning based scheduling within edge-cloud environments. Section “System architecture and proposed methodology” presents the overall system architecture, including the task model, queuing theory formulations, and resource characterization across computational tiers. Section “Problem formulation” presents the formal problem formulation, detailing the hybrid GRU-LSTM-based workload predictor and the Markov Decision Process representation of the offloading strategy. Section “Proposed AICDQN framework” describes the proposed AICDQN learning framework, including the network architecture, energy-aware task scheduler, and the training workflow. Section “Simulation and performance evaluation” outlines the experimental setup, including the simulation environment, evaluation metrics, and benchmark algorithms. This section also provides a comparative performance analysis, showing the improvements in delay, energy consumption, task completion ratio, and system stability achieved by AICDQN. Finally, section “Conclusion and future work” concludes the paper, summarizing key contributions and suggesting future enhancements including multi-agent cooperation and transfer learning for further scalability.

Related works

Task offloading and intelligent scheduling in edge-cloud environments have become vital for achieving low-latency, energy-efficient computing in modern IoT systems. The distributed and heterogeneous nature of these systems, coupled with dynamic task arrivals and limited processing capacity, presents a significant challenge for conventional static or heuristic-based offloading schemes. Traditional rule-based or queue-threshold approaches often lack adaptability to workload fluctuations, leading to resource underutilization or task failures. Recent research has explored DRL for adaptive task scheduling; however, many models lack predictive capability and fail to incorporate queue-aware or urgency-based task prioritization. Furthermore, energy efficiency remains underexplored in these DRL-based solutions. This work addresses these gaps by introducing AICDQN, an intelligent and predictive framework that integrates GRU-LSTM-based workload forecasting, real-time priority scoring, and energy-aware offloading decisions using a D3QN architecture, optimized for edge-cloud systems under uncertainty.

This section surveys key approaches in task scheduling, multi-objective optimization, machine learning-based algorithms, and task offloading strategies, emphasizing their contributions and limitations in the context of AICDQN. Classical optimization and evolutionary approaches remain relevant in cloud and large-scale scheduling. For example, genetic-algorithm (GA) based schedulers have been applied to jointly reduce makespan and energy consumption, showing good performance on small to medium-scale cloud workloads but suffering from high computational overhead while scaling3. Supervised learning has also been used to predict edge load and trigger offloading to cloud resources, improving latency by avoiding overloads on edge nodes, yet such methods depend heavily on the availability of accurate and up-to-date training data and struggle under rapidly changing conditions14.

A large body of recent work focuses on (Reinforcement Learning) RL and DRL to provide automated, adaptive offloading policies. Several algorithmic contributions propose RL variants tailored to MEC orchestration: an reinforcement-learning-based state-action-reward-state-action (RL-SARSA) scheme tackles resource management in multi-access MEC networks with the goal of minimizing combined energy and delay costs15; collaborative DRL approaches target heterogeneous edge environments to improve offloading efficiency16; enhanced DQN methods with modified replay mechanisms have been proposed for more effective resource allocation in IoT-edge systems17; Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS)-based frameworks (e.g., iRAF) have been used to autonomously learn service allocation under delay-sensitive demands18; and orchestrated DRL solutions optimize device-edge-cloud allocations to reduce system energy19. Complementary research has explored different families of DRL techniques. Discrete-action models, such as DQN, have been employed to address joint task offloading and resource allocation problems, whereas continuous-action approaches, exemplified by the DDPG, have been investigated to optimize power control and offloading strategies in multi-user environments20. Collectively, these works demonstrate the potential of DRL’s, but often assume simplified traffic models and do not always incorporate queue-aware state features or explicit urgency scoring into the decision process.

Accurate modeling of task arrivals and queueing behavior is central to meaningful performance assessment and to state design for learning agents. Traditional analytical models represent mobile devices as M/M/1 queues, fog servers as M/M/\(c\) systems, and cloud datacenters as M/M/\(\infty\) queues to analyze latency, energy, and cost under Poisson arrivals34,35. In particular, studies of MEC-enabled vehicular networks illustrate how buffering and sequential service lead to non-negligible queueing delays that cannot be ignored when evaluating offloading strategies36. Because Poisson assumptions may fail to capture correlated or bursty arrivals observed in practice, researchers have extended arrival models to Markovian Arrival Processes (MAP) and Marked MAP (MMAP) formulations to account for correlation and categorization of tasks37,38. These modeling efforts indicate that arrival correlation and queue saturation significantly influence delay and energy metrics and therefore should inform the design of RL state representations and reward functions.

Despite these advances in algorithmic and modeling, several persistent gaps remain. First, many DRL-based proposals rely on stationarity assumptions or single-type user models, limiting adaptability to heterogeneous and time-varying workloads. Second, while energy-aware methods exist, few approaches jointly optimize energy, latency, and queueing constraints at scale; achieving this balance in real time is still challenging. Third, simplified traffic models (e.g., Poisson) can lead to biased policy learning under correlated traffic, and RL agents trained under such assumptions may perform poorly in practice. Finally, training and retraining DRL agents can be data-intensive and compute-intensive, creating practical deployment barriers. These limitations motivate a combined solution that (i) anticipates correlated arrivals, (ii) encodes queueing and urgency into state and reward design, (iii) stabilizes learning under large action/state spaces, and (iv) enforces energy constraints during decision making.

The proposed AICDQN framework directly addresses these gaps. It augments the RL state with short-term load forecasts produced by a GRU-LSTM predictor to capture correlated and bursty arrivals, integrates queue-aware features and adaptive dynamic priority score \(\psi _i(t)\) that captures deadline proximity and node saturation, employs a dynamic Dueling Double DQN architecture to reduce Q-value bias and improve convergence, and implements an energy-aware scheduler with action masking to enforce runtime energy constraints. By explicitly combining predictive modeling, queue-aware state design, priority evaluation, and energy constraints within a single DRL pipeline, AICDQN aims to provide adaptive, scalable, and energy-efficient offloading policies suitable for heterogeneous multi-tier IoT-edge-cloud systems. Table 1 summarizes the strengths and limitations of existing approaches.

System architecture and proposed methodology

To enable intelligent and energy-efficient task offloading in dynamic edge-cloud environments, we propose a comprehensive system model comprising four key components: system architecture, task model, queueing behavior, and energy model. This integrated structure captures the complex dynamics of task execution and offloading decisions across distributed and heterogeneous computing resources.

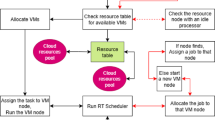

The proposed system architecture of the AICDQN framework (Fig. 2) is enhanced from39 and integrates GRU-LSTM-based workload prediction with dynamic priority scoring to proactively estimate the system load and assess task urgency. using these predictive insights, the D4QN agent makes real-time, context-aware offloading decisions, dynamically selecting the most suitable computation layer-local device (HW), edge server (ES), or cloud-based on the current system state. By combining queue-aware scheduling, proactive load forecasting, and feedback-driven task allocation, the framework minimizes task delay, reduces the drop ratio, and achieves balanced resource utilization across tiers. Furthermore, energy efficiency is enhanced through selective server activation guided by workload forecasts and by adopting offloading strategies that lower energy consumption without compromising service quality. Together, these mechanisms operate in synergy to improve resource utilization, maintain quality QoS for high-priority tasks, and ensure scalable and sustainable operation in modern edge-cloud computing environments.

System architecture

The proposed AICDQN framework enables intelligent and priority-aware task offloading in a heterogeneous hierarchical computing environment comprising IoT devices, edge servers, and cloud infrastructure. Using predictive deep reinforcement learning, the system dynamically adapts to fluctuating workloads, varying task urgencies, and changing network conditions. Its primary objectives are to minimize average task delay and energy consumption, ensure timely execution of delay-sensitive tasks, and achieve adaptive load balancing across local, edge, and cloud resources.

Architectural overview

The AICDQN framework comprises five integrated modules that form a decision making pipeline, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

-

IoT layer: task generator and dynamic priority evaluator—Handles task arrivals and assigns urgency-based priority scores.

-

System state encoder and representation layer—Integrates predicted load, resource availability, and task priority into the state vector.

-

GRU-LSTM-based load predictor—Forecasts future workloads from past queue statistics.

-

Dynamic dueling double deep Q-network (AICDQN agent)—An enhanced reinforcement learning model that extends the standard D3QN by incorporating dynamic, context and priority-aware decision making, allowing the learning of optimal offloading and scheduling policies under delay-energy-priority trade-offs.

-

Energy-constrained task scheduler—Executes final scheduling/offloading decisions while managing active, idle, and sleep states of resources.

The overall architecture, as shown in Fig. 3, illustrates the interaction among the five functional modules. In the IoT devices layer, tasks are generated and prioritized based on urgency through the Adaptive Dynamic Priority Evaluator. These tasks, together with queue states, are processed by the System State Encoder, where expedited load buffers and available resources are consolidated into a state vector. Historical workload information and past queue lengths are then passed to the Prediction Module, where the GRU-LSTM forecaster anticipates future arrivals. This predicted load, along with the encoded system state, is used by the AICDQN agent, which leverages a Dynamic Dueling Double Deep Q-Network. Unlike conventional D3QN , this dynamic variant incorporates adaptive state representations and priority-aware decomposition to derive more responsive offloading and scheduling decisions.

The Execution Layer distributes tasks hierarchically across local hardware, edge servers, or cloud resources, while the Energy-Aware Scheduler ensures efficient power utilization by dynamically switching resources between active, idle, and sleep states. Execution feedback loops continuously refine decision-making, achieving predictive, adaptive, and energy-efficient task scheduling across the IoT-Edge-Cloud continuum.

This integrated design provides the conceptual foundation for the AICDQN framework. The next section formally introduces the Task Model, which mathematically defines task arrival patterns, deadlines, computation requirements, and queue dynamics to support the subsequent problem formulation.

Task model

Mobile devices continuously generate tasks with varying urgency levels, arrival rates, and execution deadlines. Time is considered in discrete slots of fixed duration \(\delta\), and tasks arrive dynamically at the beginning of each time slot \(t \in \mathcal {T} = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots , T\}\). Let \(\mathcal {U} = \{1, 2, \ldots , U\}\) represent the set of mobile users or IoT devices, where each user \(u \in \mathcal {U}\) may generate a computational task \(\tau _i(t)\) at time \(t\). Each task \(\tau _i\) is defined as a tuple:

Where:

-

\(S_i \in \Phi = \{\phi _1, \phi _2, \ldots , \phi _N\}\) represents the set of task size in bits, where the set \(\Phi\) denotes the discrete data size domain,

-

\(\rho _i\): CPU cycles required per bit (processing density),

-

\(D_i(t) = T^{\text {deadline}}_i - T^{\text {arr}}_i\): Deadline slack in time slots (i.e., available processing window),

-

\(p_i \in \{0,1\}\): is the urgency level of the task (\(1\) for urgent/real-time, \(0\) for normal),

-

\(T^{\text {arr}}_i\): Arrival time of the task,

-

\(T^{\text {deadline}}_i\): Hard deadline by which the task must be completed.

The total computational workload of task \(i\) in CPU cycles is defined as:

where \(S_i\) denotes the task size and \(\rho _i\) is the required CPU cycles per bit.

Given a computing node \(r\) with CPU frequency \(f_r\), the execution time is:

To account for real-time execution contexts and system dynamics, an adaptive dynamic priority score \(\psi _i(t)\) is computed for each task \(\tau _i\), which combines task urgency, local queue congestion, and static priority level:

Here, \(D_i(t)\) denotes the remaining deadline slack as defined in Eq. (1), now contributing directly to the urgency component in \(\psi _i(t)\).

Where:

-

\(Q_r(t)\): Current queue length at node \(r \in \{\text {HW}, ES_1, ES_2, \dots , ES_n, \text {Cloud}\}\),

-

\(Q_r^{\max }\): Maximum allowable queue size at node \(r\),

-

\(\omega _1, \omega _2, \omega _3\): Tunable weights that adjust the influence of deadline urgency, queue load, and static priority.

Here, the term \(\dfrac{Q_r(t)}{Q_r^{\max }}\) represents the normalized congestion level at node \(r\), such that queue saturation directly increases the urgency of the task \(\tau _i\). Consequently, the AICDQN agent prioritizes the execution or offloading of tasks with higher \(\psi _i(t)\), ensuring responsiveness to the dynamics of the real-time queue.

This dynamic priority score \(\psi _i(t)\) is essential for intelligent scheduling in resource-constrained multi-tier environments, allowing the framework to reactively prioritize delay-sensitive tasks while maintaining system stability. Tasks with high static priority \(p_i = 1\), short remaining slack \(D_i(t)\), or greater \(\psi _i(t)\) values are preferentially executed on local devices or edge servers when resources permit. In contrast, less urgent tasks can be queued or directed to cloud execution depending on current congestion, predicted delay conditions, and communication overhead.

This cohesive prioritization model empowers AICDQN with intelligent situational awareness, ensuring timely and efficient task allocation across heterogeneous computing layers.

Queueing models

To capture realistic delays during task processing at different computational tiers (local hardware, edge servers, and cloud server), standard queueing theory is adopted. The queueing behavior directly impacts task scheduling decisions and is integrated into the AICDQN framework’s state representation.

Local hardware: M/M/1 queue

Each IoT device is modeled as a single-server queue with Poisson arrivals \(\lambda _{\text {HW}}\) and an exponential service rate \(\mu _{\text {HW}}\). The server utilization and queueing metrics are expressed as follows:

The expected number of tasks in the queue and the corresponding expected waiting time before a task starts execution are given by:

These expressions determine whether a task should remain local or be offloaded to avoid excessive queuing delays under high congestion.

Edge servers: M/M/c queue

Edge servers typically consist of multiple parallel processing units, and thus are modeled using the M/M/c queue. Let \(\lambda _{\text {ES}}\) be the task arrival rate, \(\mu _{\text {ES}}\) the service rate per server, and \(c\) the number of servers at the edge node.

The system utilization is defined as:

The probability that an incoming task must wait is given by the Erlang-C formula:

The average queueing delay becomes:

This delay term is directly reflected in the MDP reward design to discourage edge overloading.

Cloud delay model

This queueing model helps the AICDQN agent assess congestion and delay at the edge, enabling informed offloading decisions when both local and edge resources are saturated. Although the cloud is modeled as a \(M/M/\infty\) queue with virtually unlimited resources and negligible queuing delay, it introduces significant communication latency \(\delta _{\text {Cloud}}\), making it less suitable for delay-sensitive tasks. The total cloud processing delay is modeled as

where \(\mu _{CL}\) is the cloud service rate and the end-to-end WAN latency component \(\delta _{\text {Cloud}} = L_{\text {trans}}^{CL} + L_{\text {net}}^{CL}\) - comprising transmission delay \(L_{\text {trans}}^{CL}\) and network propagation delay \(L_{\text {net}}^{CL}\), is explicitly embedded in the reward formulation.

Resource model

The system consists of heterogeneous computing tiers including one local hardware device (HW), a multi-server edge server, and a remote cloud. The edge tier contains \(n\) parallel edge servers denoted as \(ES_j \in \{1,2,\dots ,n\}\). Each computing node \(r \in \{\text {HW}, ES_1, ES_2, \dots , ES_n, \text {Cloud}\}\) is defined by the following resource characteristics that influence offloading and scheduling performance:

-

CPU frequency \(f_r\): Processing speed of node \(r\), measured in cycles per second.

-

Maximum queue length \(Q_{max}\): The capacity of the task buffer at node \(r\). If the queue is full, new tasks can be rejected or rerouted.

-

Available energy budget \(E_r\): The remaining energy at the node, especially relevant for mobile or edge nodes with limited power.

-

Communication delay \(\delta _r\): Network delay from the task-generating IoT device to node \(r\), incorporating wireless transmission, routing, and propagation times.

-

Execution time \(T_{exec,i}^r\) from Eq. (3).

The AICDQN agent uses these parameters to learn optimal task assignment strategies. During each time interval \(t\), the agent evaluates the current system load, energy status, communication latency, and queue statistics to make intelligent real-time offloading and scheduling decisions. This ensures that both urgent and delay-tolerant tasks are handled optimally across heterogeneous resources.

Problem formulation

In this section, we formulate the task offloading and scheduling problem in the proposed AICDQN framework as a MDP to enable intelligent decision-making in a multi-tier computing architecture comprising local IoT devices, edge servers, and the cloud. The objective is to learn adaptive offloading policies that minimize execution delay, reduce energy consumption, and ensure timely processing of high-priority tasks. By modeling the environment as an MDP, we capture the spatio-temporal dynamics and heterogeneity of edge-cloud systems, allowing the agent to make sequential decisions based on observable system states and learned rewards. The subsequent subsections define the MDP components, including state and action spaces, transition dynamics, reward formulation, and analytical expressions for delay, energy cost, and priority penalties.

Load Forecaster (GRU-LSTM Module)

To ensure intelligent and proactive task scheduling, it is essential to anticipate future workload fluctuations across local, edge, and cloud layers. Static or reactive models fail to adapt to time-varying traffic patterns in IoT applications. To address this, we propose a hybrid deep learning model combining GRU and LSTM networks for accurate and robust queue load prediction. Real-time system decisions benefit significantly from foresight into upcoming computational and communication loads. Traditional heuristics or moving average techniques struggle with bursty, nonlinear, or seasonal traffic typically found in edge-assisted IoT systems. The GRU-LSTM module, integrated within the proposed AICDQN framework, generates predictive signals that directly influence offloading and scheduling behavior, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The GRU-LSTM predictive model enables:

-

Proactive offloading decisions: Anticipating congestion helps prevent task offloading or local processing bottlenecks.

-

Priority-aware adjustment: Predicted congestion influences dynamic recalibration of task urgency scores.

-

Energy optimization: Load-aware decisions help conserve battery by avoiding unnecessary offloading.

Forecasting objective

To proactively estimate the incoming workload and avoid bottlenecks, the load forecaster predicts future queue dynamics.

Input: Time-series window \(\{Q_{t-k}, \dots , Q_t\}\) , Output: Predicted arrival rate \(\hat{\lambda }_{t+1}\)

Hybrid GRU-LSTM architecture

The GRU-LSTM architecture is designed to capture both short-term fluctuations and long-term dependencies in task arrival sequences. The model receives a sequence of observed task arrival rates or queue lengths and produces a prediction for the next time step:

Where:

-

\(\hat{\lambda }_{t+1}\): Predicted arrival rate at time \(t+1\),

-

\(Q_t\): Observed task arrival or queue length at time t,

-

\(h_t\): Hidden state representing the learned load and dynamics of the system,

-

\(W_o, b_o\): Trainable parameters of the output layer,

-

\(\sigma (\cdot )\): Activation function (typically sigmoid or ReLU).

Motivation and role in AICDQN framework

The predicted task arrival rate \(\hat{\lambda }_{t+1}\) provides crucial insight into the upcoming system state, allowing the AICDQN agent to dynamically adjust its offload and scheduling strategies. Instead of reacting to congestion, the agent can proactively:

-

Redirect tasks before overloads occur,

-

Select energy-efficient computation nodes,

-

Prevent task drops due to deadline violations.

As shown in Fig. 4, the forecasted workload is fused with real-time system state inputs-such as task size, edge resource status, energy levels, and task priorities-and passed through fully connected layers for feature extraction. The architecture employs a D4QN , where the Q-value is calculated using both the value and advantage streams. The Double DQN mechanism further stabilizes learning by decoupling target value estimation. This joint architecture enables adaptive and intelligent task offloading decisions that are both priority-aware and energy-aware.

Training and optimization

The model is trained using the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss between predicted and actual arrival rates:

The optimizer (e.g., Adam) minimizes this loss over historical data collected from task generation patterns in the system.

Markov Decision Process (MDP) representation

The edge-cloud task offloading environment is modeled as a Markov Decision Process \(\textbf{M} = (\textbf{S}, \textbf{A}, \textbf{P}, \textbf{R}, \gamma )\), where \(\textbf{S}\) denotes the state space, \(\textbf{A}\) the action space, \(\textbf{P}\) the transition probability distribution, \(\textbf{R}\) the reward function, and \(\gamma \in [0,1)\) the discount factor for future rewards. The agent interacts with the environment in discrete time steps to learn an optimal policy \(\pi : \textbf{S} \rightarrow \textbf{A}\), aiming to maximize the expected cumulative reward by mapping observed states to optimal actions.

State space \(\textbf{S}\)

At each time step \(t\), the AICDQN agent observes a multidimensional system state \(S_t \in \textbf{S}\), capturing the operational context between local devices, heterogeneous edge servers, and cloud resources. The enhanced state vector is defined as:

Here, \(Q_t^{HW}, Q_t^{ES_j}, Q_t^{Cloud}\) and \(R_t^{HW}, R_t^{ES_j}, R_t^{Cloud}\) represent the queue lengths and available computational resources on the local device (HW), each edge server \(ES_j \in \{1,2,\dots ,n\}\), and the cloud, respectively. The predicted workload \(\hat{\lambda }_{t+1}\) from the GRU-LSTM model enables proactive congestion mitigation, while the dynamic priority score \(\psi _i(t)\) incorporates deadline urgency and queue saturation to emphasize real-time task handling. The remaining energy state \(E_t^r\) supports energy-aware scheduling. This comprehensive state representation ensures full visibility into system dynamics, enabling intelligent, latency-aware, and resource-efficient decision making in the MEC environment.

Action space \(\textbf{A}\)

The agent selects an action \(A_t \in \textbf{A}\) to determine the execution location of an incoming task:

-

Execute at HW: Minimum network delay but constrained computation and battery capacity,

-

Offload to \(ES_j\): \(j = 1,2,\dots ,n\); balanced transmission delay with heterogeneous edge resource capabilities,

-

Offload to Cloud: Highest communication delay due to WAN propagation but abundant processing capability.

This enhancement improves resource selection clarity in multi-edge environments and remains fully consistent with the state representation in Eq. (13), where queue and resource statuses are tracked individually for HW, each \(ES_j\), and the cloud server.

Transition dynamics \(\textbf{P}\)

The system evolves stochastically due to dynamic task arrivals, queueing behavior, wireless channel variability, and energy fluctuations. The next state is determined by:

Since explicitly modeling state transition probabilities is computationally intractable in such a complex and highly non-stationary MEC environment, a model-free reinforcement learning approach is adopted. Thus, AICDQN learns optimal policies through continuous interaction and reward feedback rather than requiring prior knowledge of the transition model.

Reward function \(\textbf{R}\)

In reinforcement learning-driven task offloading systems, the reward function serves as the primary mechanism by which the agent evaluates the quality of its actions over time. In the proposed AICDQN framework, the reward is formulated to reflect three critical objectives of edge-cloud task management: (i) minimizing execution delay, (ii) reducing energy consumption, and (iii) preserving task-level QoS by meeting the deadlines of high-priority tasks.

The delay term \(D_t\) captures both communication and computation latency, which is crucial in latency-sensitive edge applications such as real-time monitoring, autonomous control, and industrial automation. The energy term \(E_t\) penalizes actions that unnecessarily burden power-constrained IoT devices or result in excessive transmission overhead. Meanwhile, the priority penalty term \(P_t\) introduces urgency-awareness by assigning additional cost to decisions that cause deadline misses for critical tasks.

To maintain adaptive decision-making in dynamic environments, AICDQN introduces time-varying weights \(\alpha _t, \beta _t, \gamma _t\) that adjust based on current performance feedback. These weights enable the agent to learn context-sensitive priorities, such as giving greater emphasis on minimizing delay during peak load periods or prioritizing energy savings when battery levels are low. This adaptive formulation transforms the static reward model into a dynamic reward-shaping mechanism, improving learning convergence and generalization across heterogeneous conditions.

To guide agent learning, we define a scalar reward function that penalizes system inefficiencies.

Where:

-

\(D_t\): Total task delay (including queuing, transmission, and execution),

-

\(E_t\): Combined energy consumption for data transmission and computation,

-

\(P_t\): Priority penalty incurred for violating the urgency of high-priority tasks (e.g., due to deadline violations or task drops),

-

\(\alpha _t, \beta _t, \gamma _t\): Tunable weight parameters (Eqs. 17–19) used to control the influence of delay, energy, and priority penalty in the learning process.

The weights of the reward function in AICDQN are dynamically adjusted at each time step based on real-time performance feedback to reflect the relative importance of delay, energy, and priority violations.

Adaptive delay weight

The delay weight \(\alpha _t\) increases when the observed task delay \(D_t\) exceeds the acceptable delay threshold \(D_{\text {target}}\), guiding the agent to take more delay-sensitive actions during congestion.

Adaptive energy weight

The energy weight \(\beta _t\) is elevated when current energy consumption \(E_t\) exceeds the desired energy threshold \(E_{\text {target}}\), encouraging energy-efficient offloading behavior.

Adaptive priority penalty weight

\(\gamma _t\) increases proportionally to the urgency penalty \(P_t\), reinforcing the importance of meeting the deadlines for high-priority tasks, especially when violations occur frequently. This dynamic adjustment enables the AICDQN agent to remain sensitive to workload spikes and critical task demands while optimizing resource utilization and responsiveness.

Energy cost formulations \(E_t\)

The energy consumption for executing a task \(\tau _i\) depends on the selected processing tier. When a task is computed locally, energy is consumed for CPU execution. In contrast, offloading incurs wireless transmission and reception energy at the device but no local processing energy. Accordingly, the energy cost at time \(t\) is expressed as:

-

Local execution (HW tier):

$$\begin{aligned} E_t^{HW} = P_{cpu} \cdot T_{exec,i}^{HW} \end{aligned}$$(20) -

Offloading to Edge or Cloud:

$$\begin{aligned} E_t^{off} = P_{tx} \cdot T_{tx}(t) + P_{rx} \cdot T_{ack}(t) \end{aligned}$$(21)

where \(P_{cpu}\), \(P_{tx}\), and \(P_{rx}\) denote the CPU, transmission, and reception power, respectively; \(T_{exec,i}^{HW}\) is the local execution time, and \(T_{tx}(t)\) and \(T_{ack}(t)\) represent the packet transmission and acknowledgment durations. When the AICDQN agent selects an offloading action (\(A_t = 1\) or \(A_t = 2\)), the device consumes only wireless communication energy, while task execution energy is entirely handled by the edge or cloud infrastructure.

Priority penalty function \(P_t\)

Penalty is applied when urgent tasks miss deadlines or are dropped:

Here, \(\delta\) is a large penalty constant.

Cost model and objective

The reward signal is directly shaped from the cost function \(C_t\), which captures the joint effect of delay, energy usage, and urgency for each task. By minimizing the discounted sum of these per-task costs over time, the AICDQN agent learns optimal long-term scheduling behavior that balances responsiveness, efficiency, and deadline sensitivity across local, edge, and cloud computing layers.

We define the instantaneous task cost as:

where:

-

\(\alpha _t\): emphasizes delay when congestion increases,

-

\(\beta _t\): emphasizes energy when the device battery is low,

-

\(\gamma _t\): emphasizes urgency when task-drop likelihood increases.

-

\(D_t\), \(E_t\), and \(P_t\) follow the definitions provided earlier in Eq. (15).

The task scheduling objective is then formulated as minimizing the expected cumulative discounted cost:

where \(\gamma \in (0,1)\) is the discount factor ensuring future tasks contribute less than immediate ones.

Subject to:

Reinforcement learning reformulation

Using the cost structure in Eq. (23), the reward is defined as:

Thus, maximizing the reward is equivalent to minimizing long-term system cost. The optimal policy is defined as:

This ensures that the AICDQN agent learns a stable and adaptive strategy capable of prioritizing real-time tasks, reducing energy consumption, and preventing queue saturation under dynamic workload fluctuations.

The AICDQN system is designed to minimize end-to-end task delay, reduce average energy consumption without violating task deadlines, maximize the success rate of urgent tasks through dynamic priority handling, and ensure balanced workload distribution across local devices, edge servers, and the cloud. At each decision epoch \(t\), the system observes the current state \(S_t\), integrates GRU-LSTM-based predictions of future load, computes the task priority score \(\psi _i(t)\), and selects an energy-feasible action \(A_t\) through the Dueling Double DQN agent. This unified architecture empowers AICDQN to adapt effectively to real-time system dynamics and learn long-term optimal task offloading policies.

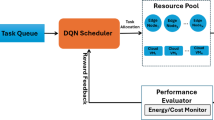

Proposed AICDQN framework

Building upon the formal MDP formulation and component-level modeling, this section presents the complete integration of the Adaptive and Intelligent Customized Deep Q-Network (AICDQN) framework, as illustrated in Fig. 5. This framework refines and extends the design presented in40. AICDQN is designed to enable intelligent, real-time, and energy-aware task offloading decisions in a multi-tier computing architecture comprising local IoT devices, edge servers, and cloud resources. The framework integrates predictive modeling, dynamic prioritization, and deep reinforcement learning with a dueling double DQN to optimize performance under dynamic workload and energy constraints. The following subsections detail the functional assembly of the core modules, focusing on how they interact to enable dynamic and intelligent scheduling under varying system dynamics.

System state encoder

As previously defined in the MDP formulation (Eq. 13), the system state \(S_t\) is a unified representation incorporating: (i) queue lengths at all computing layers, (ii) available compute and energy resources, (iii) predicted workload, and (iv) Specific urgency of the task represented by the dynamic priority score \(\psi _i(t)\). To interface with the AICDQN agent, this canonical state is transformed into an encoded feature vector \(\tilde{S}_t\) that preserves the same informational content while ensuring numerical stability and compatibility with neural network processing.

State representation

The encoded state used as input to the learning agent is derived directly from the canonical \(S_t\) of Eq. (13) by rearranging and normalizing its elements:

Where, \(E_t^{\text {avail}}\): Local energy available obtained from \(E^r_t\) in Eq. (13). This representation maintains seamless consistency with the MDP state while structuring features for efficient feature extraction and network learning.

Normalization and preprocessing

All input features are normalized using min-max scaling to facilitate training convergence and stability. Each element in \(\tilde{S}_t\) is normalized to [0, 1] using min-max scaling:

where \(S_{\min }\) and \(S_{\max }\) denote the minimum and maximum admissible limits of each feature. This preprocessing ensures balanced feature contributions, improves convergence speed, and enhances the stability of the \(\hbox {D}^4\)QN training process.

Dynamic dueling double DQN agent \((\text {D}^{4}\text {QN})\)

The proposed AICDQN agent adopts a Dynamic Dueling Double Deep Q-Network, which extends the conventional D3QN by incorporating dynamic task urgency and workload prediction into the advantage estimation process. This enhancement allows the learning agent to adapt its decisions to real-time variations in queue congestion and QoS requirements, making it more suitable for highly dynamic MEC environments compared to static D3QN and other RL baselines. The end-to-end decision workflow of the proposed D4QN-based AICDQN system is illustrated in Fig. 6.

The encoded system state \(\tilde{S}_t\), enriched with dynamic features such as task urgency, load forecasts, and energy availability, is processed by the D4QN agent. This architecture improves learning adaptability under fluctuating workloads by decomposing the Q-value into two components: a context-aware state-value function \(V(\tilde{S}_t, C_t)\) and a task-aware advantage function \(A(\tilde{S}_t, A_t, \psi _t)\), where \(C_t\) denotes environmental context (e.g., queue status, resource availability) and \(\psi _t\) indicates task-level dynamics such as urgency and deadline slack.The complete Q-value is expressed as:

This dueling architecture enables a more accurate estimation of state values, even when actions differ minimally, while the double Q-learning mechanism mitigates overestimation bias by separating action selection and evaluation. Action selection follows a masked \(\epsilon\)-greedy exploration strategy:

where \(\epsilon _t\) gradually decays to balance exploration and exploitation over time.

Algorithm 1 presents the proposed Dynamic Dueling Double DQN-Based Offloading and Scheduling (AICDQN) framework. The algorithm operates on the canonical MDP state \(S_t\) defined in Eq. (13), which embeds queue status, resource availability, predicted arrival rate, energy profile, and task urgency. Before making decisions, this state is rearranged and feature-normalized in the encoded form \(\tilde{S}_t\) following Eqs. (32, 33), ensuring stable learning dynamics.

At each decision step, the GRU-LSTM module predicts future task arrivals to capture temporal correlations in workload variation. The encoded state is partitioned into queue-related features, a context vector \(C_t\) containing resource availability and predicted load, and the dynamic priority score \(\psi _t\), allowing both congestion-awareness and QoS differentiation.

The AICDQN agent selects actions through a masked \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy, where the action feasibility mask prevents selection of energy-violating offloading choices. Interaction with the environment provides delay- and energy-aware rewards, which are stored in a replay buffer for minibatch learning. Double Q-learning mitigates Q-value overestimation, while the dueling network architecture separates state-value and action-advantage estimations, allowing the agent to distinguish between inherently beneficial states and urgency-driven action preferences. Target network updates and exploration decay progressively stabilize the learning process, ensuring convergence toward an optimal policy that yields predictive, energy-efficient, and priority-aware task offloading decisions in multi-tier edge-cloud environments.

Energy-aware task scheduler

Once an action is selected, the Energy-Aware Task Scheduler verifies its feasibility by considering the remaining battery budget and the power consumption of the selected execution destination. If a task is predicted to violate energy thresholds or face resource saturation, the scheduler may defer or locally buffer tasks to prevent battery drain while still preserving priority ordering. Thus, the scheduling policy dynamically prioritizes high-urgency tasks under constrained energy availability.

Energy models

A hardware and location-based energy model is integrated to quantify the execution cost of each task \(\tau _i\) based on its selected offload path:

Local Execution (HW):

Edge Execution (ES):

Cloud Execution (CL):

Here, the model parameters include CPU frequency f, switching capacitance \(\kappa\), transmission power \(P_{tx}^{HW}\), network power \(P_{net}\), and associated execution and transmission times.

Energy-constrained policy masking:

To avoid energy-inefficient decisions, the AICDQN agent applies a binary feasibility mask during action selection:

This mask is applied during exploration and policy evaluation to ensure that the selected actions comply with the energy constraints at the device level.

Learning workflow and convergence

The AICDQN agent is trained using an episodic reinforcement learning framework, in which it interacts with a dynamic edge-cloud environment to learn optimal task offloading strategies. In each episode, the agent observes the current canonical system state \(S_t\) (Eq. 13), encodes and normalizes it into \(\tilde{S}_t\) (Eqs. 32, 33), selects an offloading action based on the D4QN policy, receives a reward, and updates its Q-values accordingly. The reward function penalizes undesirable behaviors such as excessive task delay, high energy consumption, and dropped or violated high-priority tasks, thus guiding the agent toward latency-aware, energy-efficient, and priority-sensitive policies.

The training loop can be summarized as:

-

1.

Observe the current canonical system state \(S_t\) and construct its encoded form \(\tilde{S}_t\).

-

2.

Forecast the upcoming workload \(\hat{\lambda }_{t+1}\) using the GRU-LSTM module and update the dynamic task urgency score \(\psi _i(t)\).

-

3.

Select an offloading action \(A_t\) using a masked, priority-aware \(\epsilon\)-greedy strategy based on \(Q(\tilde{S}_t, a; \theta )\).

-

4.

Execute \(A_t\) in the environment, obtain the immediate reward \(R_t\), and observe the next canonical state \(S_{t+1}\).

-

5.

Encode and normalize \(S_{t+1}\) to obtain \(\tilde{S}_{t+1}\).

-

6.

Store the transition tuple \((\tilde{S}_t, A_t, R_t, \tilde{S}_{t+1})\) in the replay buffer \(\mathcal {B}\) and periodically update the network parameters \(\theta\) via minibatch training.

To stabilize training and avoid divergence, AICDQN incorporates two standard deep Q-learning components:

Replay buffer: A memory module that stores past experience tuples \((\tilde{S}_t, A_t, R_t, \tilde{S}_{t+1})\). By sampling training data randomly from \(\mathcal {B}\), temporal correlations are reduced, leading to improved sample efficiency and better generalization.

Target network: A separate Q-network with parameters \(\theta ^-\) is maintained and updated periodically to follow the online network parameters \(\theta\). The target network is used to compute a stable temporal-difference (TD) target:

where \(\gamma \in [0,1)\) is the discount factor that regulates long-term reward sensitivity, and t denotes the real environment timestep during interaction.

Experience replay and minibatch training: At each update step, a minibatch of size B is sampled from \(\mathcal {B}\), indexed by \(j \in \{1,\dots ,B\}\). Unlike the temporal index t, which reflects the sequential evolution of the environment, the index j denotes randomly sampled past transitions, thereby breaking temporal correlations. The mean squared TD loss for training the online Q-network is:

To further improve learning responsiveness and stability in highly dynamic environments, AICDQN incorporates adaptive parameter mechanisms. The exploration rate \(\epsilon _t\) decays with time, allowing extensive exploration during the early training stages and more focused exploitation as learning progresses. The learning rate \(\eta _t\) can also be decayed gradually to ensure smoother convergence and prevent overshooting. Additionally, the reward weights \((\alpha _t, \beta _t, \gamma _t)\)-which respectively penalize delay, energy consumption, and dropped urgent tasks-are dynamically adjusted based on deviation from desired thresholds (e.g., target delay, energy budget, or drop ratio). This adaptive feedback mechanism keeps the agent sensitive to task criticality and system performance while accelerating convergence in variable edge-cloud conditions.

Convergence and policy quality: Convergence is monitored through episode-level performance indicators such as average task delay, average energy consumption, and task drop ratio, as well as cumulative episode reward. Under standard conditions of bounded rewards, adequate exploration, and decaying learning rates, the learned policy empirically converges to a stable solution that maximizes the expected long-term return:

By jointly integrating predictive task modeling, queue-aware state encoding, dynamic dueling Double DQN updates, replay-buffer-based minibatch training, and adaptive parameter feedback, the AICDQN framework promotes robust learning behavior and produces intelligent, scalable, and context-aware task offloading decisions in heterogeneous edge–cloud environments.

Simulation and performance evaluation

This section rigorously evaluates the effectiveness of the proposed AICDQN framework under diverse operational scenarios using a realistic MEC environment. The simulation investigates the impact of AICDQN on task delay, energy efficiency, task drop ratio, and real-time task satisfaction compared to several state-of-the-art baseline algorithms.

Simulation setup

The simulation is conducted using a Python-based environment that integrates SimPy for discrete-event modeling, PyTorch for implementing the Dynamic Dueling Double DQN core of the AICDQN agent, and auxiliary libraries such as NumPy and Pandas for workload modeling and performance evaluation. The system emulates a three-tier hierarchical edge-cloud computing architecture consisting of 50 mobile devices, 5 edge servers, and a centralized cloud server.

Each mobile device generates computational tasks based on a Poisson arrival model, with urgency and resource requirements varying dynamically over time. These devices periodically transmit system state features, including current queue lengths, urgency scores, energy availability, and GRU-LSTM-based arrival forecasts, to the AICDQN agent. The agent processes this global state representation and executes a customized D4QN policy to determine delay-aware and priority-sensitive offloading actions across local, edge, and cloud layers.

The second tier, consisting of edge servers, provides low-latency processing with moderate resources and serves as the preferred execution target. The cloud server forms the third tier with significantly higher capacity but at the expense of higher transmission and propagation delay, making it suitable for overflow or low-urgency tasks. This three-tier structure allows the AICDQN agent to intelligently balance execution delay, energy consumption, and deadline violations.

The neural network model is trained using a batch size of 16, a learning rate of 0.001, and a discount factor of 0.9. An RMSProp optimizer is employed, and the \(\epsilon\)-greedy exploration rate decays gradually from 1 to 0.01, allowing efficient exploitation of the learned policies while retaining sufficient exploration. A replay buffer facilitates decorrelated minibatch updates, and a target network updated every 50 steps ensures training stability. All methods are trained and evaluated under identical stationary conditions, where the transition and cost functions remain time-invariant, ensuring a fair comparison across baselines. The training spans 1000 episodes, each with 100 time slots, providing sufficient interaction with the dynamic environment for stable convergence. The parameters used in the simulation-including task generation settings, hardware and network configurations, and learning hyperparameters-are detailed in Tables 2, 3, and 4, respectively13.

Task and scheduling parameters

Hardware and network configuration

Learning and algorithm settings

Each device uses a Dueling Double DQN agent, updated with feedback from its closest edge server. The state includes the predicted queue load (via GRU-LSTM), task priority, and available resources.

Evaluation metrics

We assess performance based on the following metrics:

-

Average task execution delay: Time from task arrival to completion.

$$\begin{aligned} \bar{D} = \frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^{N} \left( T_{\text {exec}}^i + T_{\text {queue}}^i + T_{\text {tx}}^i \right) \end{aligned}$$(43)where \(T_{\text {exec}}^i\) is the execution time, \(T_{\text {queue}}^i\) is the queueing delay, and \(T_{\text {tx}}^i\) is the transmission delay for the task i.

-

Task drop ratio: The task drop ratio \(R_{\text {drop}}\) represents the percentage of tasks that fail to meet their deadlines:

$$\begin{aligned} R_{\text {drop}} = \frac{N_{\text {drop}}}{N_{\text {total}}} \times 100\% \end{aligned}$$(44)Where:

-

\(N_{\text {drop}}\) is the number of tasks dropped due to deadline violations,

-

\(N_{\text {total}}\) is the total number of tasks generated.

-

-

Average energy consumption: The average energy consumption per successfully completed task is denoted by \(\bar{E}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \bar{E} = \frac{1}{N_{\text {succ}}} \sum _{i=1}^{N_{\text {succ}}} E_i \end{aligned}$$(45)Where:

-

\(N_{\text {succ}}\) is the number of tasks completed successfully ,

-

\(E_i\) is the energy consumed for the task i, calculated based on the offloading location (local, edge, or cloud).

-

Compared algorithms

We compare AICDQN with the following baselines:

-

DDTO-DRL 13: DDTO-DRL integrates GRU-based workload forecasting with centralized Q-network training to support delay-sensitive task offloading across edge clients, but lacks adaptive reward tuning, continuous action support, and real-time priority awareness.

-

IDDPG 41: IDDPG extends the classical DDPG for continuous task offloading decisions in MEC environments with improved stability through dual-critic learning, but lacks native support for task urgency and suffers from sensitivity to hyper parameters and sparse reward conditions.

-

PGOA 7: Employs game-theoretic utility negotiation among distributed agents to reach an offloading consensus, but coordination overhead and limited adaptability hinder its performance in real-time edge scenarios.

-

ULOOF 8: Relies on historical server utility patterns to guide offloading decisions, reducing responsiveness to real-time load fluctuations, and degrades performance in highly dynamic mobile edge networks.

-

DRL-DQN 42: A conventional Deep Q-Network that learns offloading policies based on observed rewards but lacks predictive foresight and task priority handling, making it less effective in rapidly changing environments.

Results and analysis

Convergence behavior

The convergence behavior of a reinforcement learning algorithm is a key indicator of its learning efficiency and long-term stability. In this study, the learning dynamics of the proposed AICDQN framework is evaluated against those of the traditional DQN baseline. The AICDQN agent is trained online, continuously updating its policy using real-time feedback from the edge-cloud environment. To capture its adaptability and robustness, we analyze convergence trends under different neural network hyperparameters across 1,000 training episodes, where each episode consists of multiple dynamic task arrivals.

Figure 7 presents the discounted cumulative cost per episode, where the x-axis indicates the training episode and the y-axis reflects the total cost incurred within each episode. In all settings, AICDQN consistently converges faster and reaches a lower cost level than the DQN baseline. This improvement stems from its dynamic priority-aware advantage learning and workload prediction capability within the D4QN architecture. Specifically, in Fig. 7a, we examine the effect of the learning rate on the convergence speed. A learning rate of (\(1\times 10^{-3}\)) offers the most balanced trade-off, allowing rapid cost reduction while preserving training stability. In contrast, a lower learning rate (for example, \(1\times 10^{-4}\)) results in slow convergence, while a higher learning rate (for example, \(1\times 10^{-1}\)) leads to unstable learning dynamics and divergence, ultimately increasing the cumulative cost beyond that of the baseline DQN. These observations validate the need for adaptive learning rate control, which is a key feature embedded in the AICDQN model.

Figure 7b illustrates the impact of varying batch sizes on the convergence behavior of AICDQN. As the batch size increases from 2 to 8, the convergence speed improves significantly without sacrificing learning accuracy. However, larger batch sizes (for example 32) yield only marginal benefits while incurring higher computational and memory overhead. Therefore, a moderate batch size of 8 offers an effective trade-off between convergence efficiency and resource consumption, aligning with the lightweight and scalable learning requirements of edge computing systems.

Figure 7c compares different optimizers in terms of cumulative cost. Optimizers are algorithms used to adjust the weights of a neural network during training by minimizing the loss function, thereby influencing both the speed and stability of convergence. Among the tested methods, Gradient Descent (GD), RMSProp, and Adam, the Adam optimizer consistently achieves the lowest cumulative cost and exhibits faster and more stable convergence. This result emphasizes the critical role of the optimizer choice in stabilizing the estimate of the value function within the Dueling Double DQN architecture. Using Adam, AICDQN ensures robust and responsive policy learning, which is essential in highly dynamic and delay-sensitive edge-cloud scenarios.

Finally, Fig. 7d analyzes the effect of parameter update frequency. Interestingly, reducing the update frequency from every time slot to once every 100 slots has only a minor influence on overall learning performance. This resilience is attributed to the experience replay buffer, which enables the agent to benefit from historical transitions rather than relying solely on immediate feedback. As a result, communication overhead between mobile devices and edge servers is significantly reduced, making AICDQN particularly effective in bandwidth-constrained environments.

Overall, the convergence analysis confirms that AICDQN not only learns faster than baseline DQN, but also remains robust across diverse training configurations. By appropriately tuning hyperparameters such as learning rate, batch size, optimizer, and update frequency, AICDQN achieves adaptive, scalable, and resource-efficient task scheduling, making it highly suitable for real-time edge-cloud applications.

Performance evaluation under varying number of mobile devices

To evaluate the adaptability and robustness of the proposed AICDQN framework compared to existing scheduling methods under varying mobile device densities, the number of mobile clients is scaled from 10 to 150. This setup enables a comprehensive evaluation of the task drop ratio, execution delay, and energy consumption as system load intensifies.

As illustrated in Fig. 8, the following three key performance metrics are analyzed:

Ratio of dropped tasks: As shown in Fig. 8a, the task drop ratio increases across all algorithms as the number of mobile devices grows, reflecting the rising competition for edge–cloud resources. AICDQN consistently achieves the lowest average drop ratio of 6.65%, thanks to its predictive offloading and queue-aware decision-making. Compared to DDPG and PGOA, AICDQN reduces the drop ratio by 79.8% and 79.7%, respectively. Against ULOOF and DDTO-DRL, it offers improvements of 79.0% and 62.6%, respectively. Even against DRL, a learning-based method, AICDQN shows a 48.0% improvement, highlighting its superior adaptability in overload conditions.

Average delay analysis: Delay results are illustrated in Fig. 8b. As mobile density increases, average task delay rises due to increased queuing and contention. AICDQN achieves the lowest average delay of 0.536 seconds, leveraging foresight-driven scheduling and dynamic priority scoring. Compared to PGOA and ULOOF, AICDQN reduces delay by 24.2% and 22.2%, respectively. Compared to other RL-based models, delay is reduced by 14.3% over DDPG, 10.4% over DRL, and 7.7% over DDTO-DRL, confirming its efficiency in latency-sensitive edge computing.

Average energy consumption: Energy consumption trends are presented in Fig. 8c. As the device count increases, energy usage rises across all schemes due to higher task arrivals and offloading activity. AICDQN maintains the lowest average energy usage of 0.01043 units, due to its integrated energy-aware task scheduling. This represents a 18.6% reduction in PGOA, 15.3% in ULOOF, 13.2% in DRL, and 5.4% over DDPG. Even compared to highly optimized DDTO-DRL, AICDQN achieves a 0.94% improvement, showcasing its meticulous balance between performance and energy efficiency.

This comprehensive evaluation demonstrates that the proposed AICDQN framework exceeds heuristic and deep reinforcement learning-based baselines under increasing mobile device load. As summarized in Table 5, by integrating GRU-LSTM-based load forecasting, dynamic task prioritization, and Dueling Double Deep Q-Network learning, AICDQN significantly reduces task drops, shortens execution delay, and lowers energy consumption, making it exceptionally well-suited for dynamic, dense IoT-edge environments.

Varying task arrival rates

In mobile edge computing, fluctuating task arrival probabilities significantly impact system performance, especially in terms of task drops, latency, and energy usage. As illustrated in Fig. 9 and summarized in Table 6, the proposed AICDQN (Adaptive and Intelligent Deep Q-Network) model is evaluated against state-of-the-art methods such as PGOA, ULOOF, DRL, DDPG, and DDTO-DRL. Below is a detailed theoretical comparison of AICDQN’s improvement over these methods.

Dropped task ratio analysis: The Dropped Task Ratio is a critical metric indicating how well an algorithm manages task load and prevents system overload. As shown in Fig. 9a , the proposed AICDQN demonstrates a significant advantage over all baseline algorithms in reducing dropped tasks across all arrival probabilities. Specifically, AICDQN achieves an average 72.21% improvement over PGOA, which exhibits the highest drop rates due to its limited adaptability to dynamic traffic. Compared to ULOOF, the drop ratio reduction is 67.52%, showcasing AICDQN’s better queue-aware scheduling and prioritization. Similarly, compared to the reinforcement-based DRL method, AICDQN achieves a 54.89% improvement, reflecting its superior reward design and convergence behavior. Even with more advanced models such as DDPG and DDTO-DRL, AICDQN outperforms them by 60.31% and 57.31% respectively. These improvements underscore AICDQN’s robust learning capability to intelligently offload and schedule tasks in real-time, even under highly dynamic arrival conditions.

Average delay analysis: Delay trends under different arrival probabilities are depicted in Figure 9b, where AICDQN consistently achieves the lowest latency compared to all baseline models, underscoring its suitability for delay-sensitive edge computing scenarios. Specifically, it reduces the delay by 18.75% compared to PGOA, which lacks adaptive decision-making and often overloads a subset of nodes. AICDQN also outperforms ULOOF by 13.76%, and DRL by 9.72%, indicating its more refined policy learning and better state-space awareness. The improvement over DDPG stands at 9.72%, while over DDTO-DRL it achieves 5.28% delay reduction. These results stem from AICDQN’s ability to anticipate system bottlenecks and schedule latency-sensitive tasks to edge resources with the lowest estimated delay. Its adaptive and intelligent design ensures that task prioritization and placement decisions consistently favor low-latency paths, contributing to an overall faster execution time across varying traffic intensities.

Average energy consumption analysis: As shown in Figure 9c, AICDQN records the lowest average energy consumption across all load conditions, consistently surpassing both heuristic and reinforcement learning-based baselines. Compared to PGOA, AICDQN reduces energy consumption by 57.74%, a significant savings that reflects its ability to avoid unnecessary computation and redundant offloading. Against ULOOF, the improvement is 55.02%, and against DRL, AICDQN saves 52.74% energy, thanks to its energy-aware reward design that actively penalizes power-intensive actions. Even when benchmarked against advanced deep reinforcement learning algorithms, AICDQN maintains its edge, showing a 6.67% improvement over DDPG, and a 4.27% reduction compared to DDTO-DRL. These gains demonstrate how AICDQN effectively learns to utilize idle server states and reduce execution overhead, ensuring energy-efficient scheduling even under high system loads and fluctuating task arrival rates.

Performance evaluation under varying task deadlines

Performance evaluation under varying task deadlines is a critical component of any task scheduling strategy in edge-cloud environments. As shown in Fig. 10 and summarized in Table 7, it ensures that the system can effectively adapt to real-time constraints, prioritize critical tasks, and make intelligent offloading decisions. By incorporating this evaluation, frameworks like AICDQN can demonstrate not only theoretical soundness but also practical applicability in latency-sensitive and resource-constrained edge environments.

Dropped task ratio analysis: Figure 10a shows that, under stricter task deadlines, AICDQN achieves the lowest drop ratio, resulting in significant improvements compared to all baseline approaches. In particular, AICDQN achieves an impressive 81.25% improvement over PGOA, which struggles with adaptive deadline handling. Similarly, ULOOF is outperformed by 70.83%, reflecting AICDQN’s superior ability to manage task queues and prioritize urgent deadlines. Although traditional DRL provides moderate deadline awareness, AICDQN still reduces dropped tasks by 19.17%, indicating more robust real-time adaptability. More advanced learning models such as DDPG and DDTO-DRL are also outpaced by 59.63% and 25.05% respectively, showing that AICDQN’s integration of deadline-awareness into its reward shaping and task mapping decisions leads to a highly reliable task completion strategy.

Average delay analysis: As illustrated in Fig. 10b, AICDQN consistently achieves the lowest average delay across varying deadline constraints, clearly outperforming conventional models. It shows a 31.35% improvement over PGOA, which lacks intelligent deadline-based resource allocation. Similarly, AICDQN outperforms ULOOF by 25.56%, highlighting the benefits of its adaptive delay-sensitive offloading mechanism. Compared to DDPG, AICDQN achieves the highest improvement in delay-34.32%, showcasing its effective temporal policy learning. Interestingly, AICDQN also shows a 20.44% advantage over DDTO-DRL, which incorporates deadline tolerance, but lacks dynamic attention to critical latency thresholds. However, compared to DRL, AICDQN experiences a 2.44% decrease in delay performance. This slight deviation may result from DRL’s shorter delay in specific deadline conditions, though at the cost of higher task drop ratios or energy inefficiency. Nevertheless, AICDQN maintains an optimal trade-off between delay, success rate, and energy.

Energy consumption analysis: Figure 10c highlights AICDQN’s clear advantage in minimizing energy consumption under strict deadline constraints, reinforcing its efficiency over competing methods. Reduces average energy consumption by 21.97% compared to PGOA, which performs redundant offloading due to its reactive policies. The model also shows a 14.17% improvement over ULOOF, and 14.88% over DDPG, highlighting how AICDQN intelligently leverages energy-aware decisions without compromising task urgency. Additionally, AICDQN exceeds both DRL and DDTO-DRL with a 6.36% improvement each, illustrating its refined trade-off between execution urgency and resource conservation. These gains stem from AICDQN’s adaptive control over resource utilization and its ability to put idle nodes into energy-saving modes when not required, thereby maintaining sustainability under real-time deadline variations.

Discussion and insight

In dynamic and resource-constrained edge computing environments, the proposed AICDQN framework introduces a novel, multidimensional task scheduling strategy tailored for real-time, latency-sensitive applications. At its core, AICDQN integrates hybrid GRU-LSTM-based load forecasting to anticipate future workload trends, enabling proactive task allocation before congestion arises. Coupled with this, a dynamic priority-aware scheduling mechanism evaluates task urgency, deadline proximity, and queue status, ensuring that critical tasks are processed with minimal delay.

The strength of AICDQN’s lies in its queue-aware MDP formulation, which models computing resources at multiple tiers to capture realistic stochastic behavior. Specifically, local devices are represented as \(M/M/1\) systems, edge servers as \(M/M/c\) systems, and the cloud as \(M/M/\infty\) system to reflect its virtually unlimited processing capacity with negligible queuing delay. This hierarchical modeling enables the agent to make latency-sensitive, resource-aware, and energy-conscious offloading decisions. To further optimize decision-making under dynamic workloads, the framework employs an enhanced Dueling Double DQN architecture. By decoupling state and advantage functions, this approach stabilizes the learning process and mitigates Q-value overestimation, a common pitfall in reinforcement learning–based scheduling. Moreover, AICDQN incorporates an energy-aware multi-tier offloading strategy that intelligently balances task distribution across local, edge, and cloud resources. Energy efficiency is achieved by exploiting dynamic low-power state transitions, ensuring minimal consumption when nodes are idle.

Empirical evaluations show that AICDQN substantially outperforms baseline methods under various operating conditions, including varying task arrival rates, deadlines, and mobile device counts. Under varying task arrival probabilities, AICDQN achieves a reduction of up to 72.21% in dropped tasks, an improvement of 18.75% in average delay and a savings of 57.74% in energy, with the largest gains observed against PGOA. In deadline-sensitive experiments, AICDQN attains up to 81.25% fewer dropped tasks compared to PGOA, 36.27% reduced average delay compared to DDPG, and 21.97% lower energy consumption compared to PGOA. With increasing numbers of mobile devices, AICDQN maintains strong robustness, reducing dropped tasks by up to 79.83% compared to DDPG, lowering the average delay by 24.18% compared to PGOA, and achieving energy savings of up to 18.60% compared to PGOA. Improvements are consistently the largest compared to heuristic baselines such as PGOA and ULOOF, while gains against advanced RL-based methods including DRL, DDPG, and DDTO-DRL are more moderate, particularly in energy efficiency.

Overall, the results highlight that AICDQN effectively balances task success, delay, and energy consumption, while demonstrating strong scalability under higher device loads. They further affirm its ability to adaptively manage edge-cloud task scheduling, offering a resilient combination of responsiveness, efficiency, and reliability. With its modular, foresight-driven design and reinforcement learning backbone, AICDQN emerges as a compelling solution for intelligent edge computing applications such as smart cities, industrial IoT, and autonomous systems.

Conclusion and future work

This study presented AICDQN, an Adaptive and Intelligent customized Deep Q-Network framework designed for priority-driven, energy-efficient task offloading in dynamic edge-cloud environments. The framework holistically addresses the challenges of latency, task drop ratio, and energy trade-offs in mobile edge computing by integrating several key innovations. First, a hybrid GRU-LSTM-based load forecasting module was developed to capture temporal variations in task arrivals, enabling anticipatory decision-making by the agent. Second, AICDQN employs a dynamic priority-aware scheduling mechanism that considers urgency, deadline proximity, and queue status, ensuring that critical and real-time tasks are serviced promptly. Furthermore, edge and cloud resources are modeled through a queue-aware Markov Decision Process based on \(M/M/1\), \(M/M/c\), and \(M/M/\infty\) systems, which capture the stochastic dynamics of local devices, parallel edge servers, and virtually unlimited cloud resources. To enhance stability and mitigate Q-value overestimation, the framework employs an enhanced Dueling Double DQN for robust learning under dynamic workloads. Finally, the agent is guided by an energy-aware multi-tier offloading strategy that intelligently distributes tasks across local, edge, and cloud resources, while conserving energy through adaptive idle-state transitions. Collectively, these innovations enable AICDQN to provide scalable, intelligent, and energy-efficient task scheduling in highly variable edge-cloud environments.