Abstract

This study evaluates water quality and human health risks at the Betwa–Yamuna confluence in Hamirpur District, India, using monthly data collected from June 2023 to May 2024. Physicochemical parameters (pH, EC, TDS, temperature) and trace metals (As, Pb, Cd, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni, Zn) were assessed against WHO and USEPA standards. Arsenic ranged from 0.001–0.011 mg/L and exceeded the WHO limit (0.01 mg/L) in several samples, while Pb (0.0004–0.012 mg/L) occasionally exceeded its guideline. EC exceeded 1200 µS/cm and TDS surpassed 500 mg/L during pre-monsoon months, indicating strong solute enrichment under low-flow conditions. Non-carcinogenic risk assessment showed median HQ values for arsenic of 0.98 for children and 0.42 for adults, with 95th percentiles reaching 2.28 and 0.97, respectively. Children’s HI values exceeded 1.0 in all seasons and surpassed 2.0 during pre-monsoon. Carcinogenic risk for arsenic exceeded the USEPA threshold (1 × 10⁻4) in 38% of adult and 9% of child Monte Carlo simulations. Probabilistic analysis (10,000 iterations) indicated HI > 1 in 67% of child runs and 23% of adult runs. The results demonstrate substantial health risks, particularly for children, and highlight the urgent need for arsenic and lead source control, seasonal water quality monitoring, and community-level drinking water treatment, with priority given to child-focused risk protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rivers in India are lifelines for domestic, agricultural, and industrial needs, but they are increasingly threatened by pollution arising from rapid urbanisation, agricultural intensification and industrial expansion. Among the most serious contaminants are metals such as arsenic (As), lead (Pb), and cadmium (Cd), which are toxic even at trace levels and pose serious risks to human health1,2,3,4. These metals originate from both natural processes, such as weathering and sediment mobilisation, and anthropogenic activities, including mining, fertilizer use, untreated sewage and industrial discharges5,6,7,8,9,10. Once introduced into river systems, metals are persistent, bio-accumulative, and capable of causing long-term health effects ranging from neurological and developmental damage to kidney dysfunction and cancer1,3,4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. In India, seasonal variability linked to the monsoon further complicates pollution dynamics, with high flows diluting contaminants and low flows amplifying their concentrations. Consequently, rivers often alternate between periods of apparent safety and episodes of severe health risk, exposing millions of people who rely directly on untreated water for drinking and domestic use.

Despite the recognised importance of rivers as a resource and the well-established toxicity of heavy metals, risk-focused assessments at river confluences remain limited. Confluences are hydrologically dynamic zones where contaminants from different catchments interact, mix, and sometimes intensify, potentially creating hotspots of contamination18,19,20. Yet, much of the existing research in India has focused either on individual rivers or on general water quality indices, often overlooking the combined risks posed by multiple metals at strategic mixing points8,10,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. This gap in knowledge means that communities depending on confluence waters for drinking or irrigation may be exposed to risks that remain poorly characterised and underestimated. The lack of detailed risk-based studies not only hinders scientific understanding of pollutant behaviour at confluences but also limits the development of effective water management and public health interventions specifically designed for such critical locations.

The present study addresses this gap by conducting a year-long, systematic water quality assessment at the Betwa–Yamuna confluence in Hamirpur District, India28,29,30. The specific objectives of this study are to:

-

Evaluate the compliance of key physicochemical parameters and dissolved metals against the World Health Organization (WHO) drinking water standards35;

-

Quantify non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks for both adults and children using established United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)/WHO frameworks36,37;

-

Model uncertainty and variability in exposure and risk estimates using Monte Carlo simulations, providing probabilistic insights beyond conventional deterministic approaches38,39,40.

Together, these three objectives establish a comprehensive baseline for water safety at one of northern India’s important river confluences. The results highlight seasonal and site-specific vulnerabilities and provide evidence-based guidance for targeted monitoring, treatment interventions, and long-term risk management strategies.

Materials and methods

Study area and data

Parameters used in this study reflect both general water quality indicators and contaminants of recognised health concern. Physicochemical variables such as pH, electrical conductivity (EC), total dissolved solids (TDS) and temperature provide baseline information on the ionic strength, solute concentration and stability of the aquatic environment, which are critical for understanding seasonal changes in dilution and evaporation. Trace metals, including arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb), were prioritised due to their toxicity and frequent exceedance of drinking water standards in South Asian River systems1,2,16,41,42,43,44. Additional elements such as Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni and Zn were included to capture broader geochemical variability and to assess potential contributions from both natural sources, e.g., weathering, sediment mobilisation, and anthropogenic inputs, e.g. industrial discharges and agricultural runoff.

Sample collection and analysis

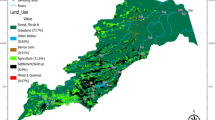

Surface water samples were collected monthly from June 2023 to May 2024 at a depth of approximately 20 cm from three monitoring locations: Betwa River (25°56′43″ N, 80°09′14″ E), Yamuna River before confluence (25°57′29″ N, 80°09′23″ E) and Yamuna River after confluence (25°55′34″ N, 80°14′23″ E) (Fig. 1). These locations were selected to monitor seasonal water quality variations and mixing behaviour before and after the confluence point in the Hamirpur district, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Study area maps: (a) India with an inset of the Ganga plains; (b) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of the Ganga plain highlighting the study area DEM image was downloaded from https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/. and modified using CorelDraw 2023; (c) Sampling locations along the Betwa and Yamuna rivers, both upstream and downstream of their confluence, in Hamirpur District, Uttar Pradesh, India (Map created using ArcGis 10.8.2).

Water samples were collected using pre-cleaned 50 mL narrow mouth high-density polyethylene bottles, each sealed with an inner cap and secured using waterproof tape to prevent evaporation and atmospheric exchange. After collection, all samples were stored at room temperature in dark conditions until laboratory analysis.

Prior to sampling, all bottles were acid-washed with 10% nitric acid, rinsed thoroughly with deionised water, and air-dried to prevent metal contamination. Field blanks and duplicate samples were collected periodically to verify sampling precision and contamination control. Physicochemical parameters (pH, EC, TDS and temperature) were measured following standard APHA procedures using calibrated portable meters45. Trace metal analysis (As, Cd, Pb, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Ni and Zn) was performed at the Geochemistry lab of Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP) after acid digestion using standard laboratory protocols. Instrument calibration was verified using multi-element standard solutions, and analytical accuracy was assessed using procedural blanks and replicate measurements, with relative standard deviations maintained within ± 5%.

Sampling at monthly intervals across all hydrological seasons allowed for the detection of temporal trends, including low-flow enrichment during pre-monsoon periods and dilution during the monsoon. The inclusion of three strategically positioned sites, Betwa, Yamuna upstream and the confluence, enabled comparative assessments of tributary contributions and downstream mixing effects. This spatial and temporal coverage ensured a robust dataset for subsequent health risk modelling, statistical interpretation and Monte Carlo simulations, providing a comprehensive view of water quality dynamics at this critical river junction.

WHO and USEPA standards

Although national regulatory limits exist under the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS), this study adopts WHO and USEPA guideline values to ensure international comparability and robust toxicological interpretation. Notably, the second revision of the BIS drinking water requirements has been upgraded to closely align with internationally recognised benchmarks, including WHO guidelines, USEPA standards, EU Directives, and the Indian Manual on Water Supply and Treatment. This regulatory harmonisation supports the application of WHO and USEPA frameworks for risk assessment in the Indian context.

The water quality parameters measured in this study were systematically evaluated against benchmark guideline values established by the World Health Organization (WHO)35 and, where appropriate, by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA)36,37. These international standards are widely recognised as the most authoritative references for defining safe limits of contaminants in drinking water and serve as the foundation for assessing potential human health risks. The WHO guidelines provide maximum permissible concentrations for critical trace metals such as – As (0.01 mg/L), Cd (0.003 mg/L) and Pb (0.01 mg/L) (Table 1), all of which are classified as priority pollutants due to their chronic toxicity and well documented impacts on human health, including cancer, kidney dysfunction, and neurological disorders1,11,13,14,15,16,17,41,42,43,44,46. Similarly, physicochemical parameters such as pH, EC and TDS are also compared against WHO thresholds to assess the overall suitability of the water for consumption, as deviations from the recommended ranges can affect both palatability and long-term health outcomes. It should be noted that the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS: IS 10,500:2012, revised 2015) does not prescribe a direct guideline value for EC in drinking water. Instead, BIS regulates TDS with an acceptable limit of 500 mg/L and a permissible limit of 2000 mg/L in the absence of an alternative source47. Because EC is strongly and empirically related to TDS, it is widely used as a supporting proxy indicator of salinity and mineralization rather than a regulated toxicological parameter. Therefore, in this study, EC is interpreted in conjunction with TDS and WHO guideline ranges to assess overall mineral load, aesthetic quality, and seasonal salinity variation rather than as a parameter with a direct health-based regulatory limit. The USEPA standards were incorporated where supplementary toxicological data or slope factors for carcinogenic risk assessment were required, ensuring that both non-carcinogenic (HQ, HI) and carcinogenic (CR) health risk indices were calculated within a robust and internationally accepted framework. This approach ensures that the evaluation of the Betwa-Yamuna water quality not only reflects local environmental conditions but also meets the standards necessary for international comparability, thereby highlighting the extent to which water in this system poses risks to public health under current usage conditions.

Health risk assessment (standard USEPA/WHO framework)

Health risk assessment in this study was conducted following the standard methodology prescribed by the USEPA and WHO, distinguishing between non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks. Four main indices were used to quantify risk: the Average Daily Dose (ADD), Hazard Quotient (HQ), Hazard Index (HI) and Carcinogenic Risk (CR). The ADD represents the estimated daily intake of a contaminant through water ingestion and was calculated using Eq. (1):

where C is the contaminant concentration (mg/L), IR is ingestion rate (L/day), EF is exposure frequency (days/year), ED is exposure duration (years), BW is body weight (kg) and AT is averaging time (days) (Table 2). Non-carcinogenic risks were determined using Eq. (2)

with HQ < 1 indicating negligible risk and HQ > 1 suggesting possible adverse health effects. Table 3 presents the reference doses (RfDs) for each contaminant. Cumulative risks from multiple contaminants were captured using the Hazard Index (HI = ΣHQ). Carcinogenic risks were estimated using Eq. (3)

where SF is the slope factor (mg/kg/day)⁻1—Table 4 lists the SFs used for carcinogenic metals. CR values within the range of 1 × 10⁻⁶ to 1 × 10⁻4 were considered acceptable, while values above 1 × 10⁻4 were interpreted as indicative of high concern. This dual framework allows for a comprehensive evaluation of both chronic non-cancer outcomes and long-term cancer risks associated with exposure to contaminated drinking water.

Monte Carlo simulation setup

Monte Carlo simulations were carried out to incorporate uncertainty and variability in both contaminant concentrations and human exposure parameters, providing a probabilistic complement to the deterministic risk assessment38,39,40,48,49. Contaminant concentrations were represented using lognormal distributions, consistent with their typically skewed environmental behaviour, while exposure parameters such as ingestion rate, exposure frequency and body weight were modelled as normal or lognormal distributions depending on their variability reported in literature.

All stochastic simulations were implemented using Python (version 3.10), with numerical computation handled using the NumPy and SciPy libraries, and data processing performed using Pandas. Random sampling from prescribed distributions was conducted using pseudo-random number generators with fixed seeds to ensure reproducibility. Each simulation was iterated 10,000 times to generate stable probability distributions for risk indices. The iteration count (N = 10,000) was selected based on convergence testing, which showed that percentile estimates (P50 and P95) stabilised beyond 8,000 iterations.

The outputs included central tendency measures such as medians, upper-bound estimates such as the 95th percentiles (P95), and exceedance probabilities for key thresholds, specifically HQ > 1 and HI > 1 for non-carcinogenic risk, and CR > 1 × 10⁻4 for carcinogenic risk as recommended by WHO and USEPA guidelines. For each contaminant and population group (adults and children), ADD, HQ, HI, and CR were recalculated within each iteration using randomly sampled exposure parameters and concentration values, producing full probabilistic risk distributions rather than single-point estimates. Simulation outputs were visualised using probability density functions, cumulative distribution functions, and exceedance probability plots, allowing direct interpretation of uncertainty, tail-risk behaviour, and threshold exceedance likelihood.

Results

Water quality

Table 5 presents the WHO guideline values alongside the observed ranges of physicochemical and metal concentrations in the Betwa-Yamuna confluence dataset. Across the 12-month monitoring period, several core parameters remained within acceptable levels, such as pH, which largely respected the WHO recommended range of 6.5–8.5. However, other indicators sometimes exceeded safe limits; EC and TDS, for example, sometimes rose above thresholds during the pre-monsoon months, reflecting the concentration of solutes under conditions of high evaporation and reduced discharge. These exceedances signal that even though the rivers receive substantial dilution during the monsoon, water quality stress returns in drier months, when anthropogenic and geogenic inputs accumulate within the reduced flow volume.

The most concerning findings relate to As, Pb and Cd, given their well-documented toxicity and strict WHO drinking water guidelines (0.01 mg/L for As and Pb, 0.003 mg/L for Cd). Arsenic concentrations in this dataset ranged from 0.0006 to 0.0112 mg/L, with several samples approaching or slightly exceeding the 0.01 mg/L limit. Lead values were mostly below 0.005 mg/L, but occasional peaks reached 0.0108 – 0.0124 mg/L, going over the WHO threshold. In contrast, cadmium remained comparatively low, with concentrations as low as 0.0003 mg/L, consistently below the 0.003 mg/L guideline. Spatially, exceedances of As and Pb were more prevalent at the Yamuna and confluence sites than at the Betwa, suggesting cumulative contamination from upstream activities. These results point to a combination of natural mobilisation from sediments and anthropogenic inputs, including agricultural runoff, untreated effluents and industrial discharges. Importantly, the recurrence of values near or above guideline levels highlights chronic pollution risks that, if untreated, could compromise drinking water safety.

Descriptive statistics for all parameters (Table 6) highlight pronounced variability in the dataset, reflecting both natural hydrological fluctuations and localised pollution events. Mean EC values exceeded 900 µS/cm at the Yamuna and confluence sites, approaching the guideline threshold, highlighting persistent solute enrichment during periods of reduced flow. TDS followed a similar pattern, with high interquartile ranges suggesting variability across months rather than uniform exceedance. Metals such as As and Pb displayed strongly skewed distributions, where most samples clustered near lower values, but occasional sharp peaks indicated episodic contamination. These spikes may result from stormwater flushing of contaminated sediments, untreated sewage releases or seasonal agricultural runoff entering the rivers. The temporal dynamics are further illustrated in Fig. 2, which presents time series trends for selected parameters. EC and TDS increased steadily in the pre-monsoon months, consistent with evaporative concentration and reduced dilution capacity. In contrast, metals such as As, Pb, and Cd peaked intermittently during dry seasons, but dropped significantly with the onset of the monsoon when high rainfall and discharge diluted contaminant loads. These patterns confirm the dual influence of hydroclimatic cycles and anthropogenic pressures on water quality: natural seasonal variability controls baseline concentration shifts, while human inputs drive episodic exceedances. The concurrent rise in EC, TDS, and dissolved metals during the pre-monsoon season indicates strong evaporative concentration effects under high temperature and low-flow conditions, which intensify solute accumulation in the river water. Together, the statistical summaries and time series plots provide a clear picture of fluctuating water quality that intermittently breaches safe thresholds, with implications for drinking water safety.

WHO standards and exceedance frequencies

Compliance with WHO standards, summarised in Table 7, highlights the persistent and widespread contamination of the Betwa-Yamuna confluence system. Exceedance analysis showed that iron surpassed guideline values in 100% of the samples, arsenic and lead in approximately 6%. These levels of non-compliance are alarming, given the well documented health risks of chronic exposure to these metals13,50, including carcinogenic and neurological impacts5,11. Even parameters such as EC and TDS, which are not toxic but reflect salinity and mineral loading51, exceeded thresholds in a significant fraction of samples, indicating broader water quality stress that can affect domestic and agricultural use. Overall, exceedances were most pronounced during the pre-monsoon season, decreased sharply during the monsoon due to dilution, and re-emerged at moderate levels during the post-monsoon and winter periods.

The temporal pattern of exceedances shows that risks are not evenly distributed throughout the year but are strongly linked to hydrological cycles. The pre-monsoon and winter months, when flows are reduced and dilution capacity is limited, showed the highest frequency of non-compliance. In these periods, pollutant concentrations became more influential due to both evaporative enrichment and sustained anthropogenic inputs. By contrast, the monsoon months provided partial relief, as high discharge diluted contaminants and temporarily lowered exceedance rates. However, the persistence of high concentrations outside the wet season highlights a chronic exposure risk for downstream populations, emphasising the need for continuous monitoring and interventions targeting both point and diffuse pollution sources.

The patterns confirm that the study area faces chronic water quality challenges, with implications for drinking water safety and ecosystem health. Importantly, the fact that exceedances were recorded for As and Pb aligns with previous findings in north Indian rivers, where untreated effluents, agricultural inputs and geogenic release from sediments contribute to contamination8,21,25,26,52,53. The elevated As concentrations observed during low-flow and pre-monsoon conditions likely reflect enhanced desorption of As from iron oxide phases under increasingly reducing conditions, combined with limited dilution during periods of reduced discharge.

Non-Carcinogenic health risk assessment

Hazard quotients

Hazard quotients for individual metals are summarised in Table 8, with corresponding scatterplots shown in Fig. 3. The analysis indicates that arsenic presents the most consistent risk, with median HQ values of 0.42 for adults and 0.98 for children, and maxima exceeding 1.0 in both groups. Lead produced lower HQ values overall, with means well below unity, though children’s upper range approached 0.24. Cadmium showed very low HQs across all metrics, remaining two orders of magnitude below the threshold of 1.0. Other metals such as Fe and Mn displayed sporadic high values (child maximum HQs of ~ 2.0 for Fe and ~ 0.43 for Mn), but these were occasional rather than persistent exceedances. These findings suggest that non-carcinogenic risks in this system are dominated by arsenic exposure, with secondary but less consistent contributions from Fe and Mn, while Pb and Cd remain below critical thresholds. This pattern is broadly consistent with South Asian River studies that identify arsenic as the most significant chronic waterborne contaminant16,27,41,43,44.

Children’s HQs were systematically higher than adults’ across nearly all metals, with mean HQs roughly double for As and Fe. For instance, the 95th percentile HQ for As in children reached 2.28 compared to 0.98 in adults, indicating a substantially higher risk burden for younger age groups. These differences reflect children’s higher water intake relative to body mass and their increased physiological sensitivity to toxic exposures. The results emphasise the necessity of age-stratified risk assessments, as children may experience significant health effects even when adult HQs remain below critical thresholds. This disproportionate vulnerability highlights the urgency of interventions targeted at communities with high child exposure, particularly where river water is consumed untreated.

The results collectively demonstrate that ingestion of untreated river water poses non-carcinogenic health risks, most critically from arsenic. While Pb and Cd remain below guideline thresholds in this dataset, arsenic exceeded the HQ = 1.0 benchmark in a significant proportion of child cases, with maximum values approaching 2.5. High HQs for Fe and Mn, though less frequent, point to additional stressors that may compound risk under low-flow or polluted conditions. These findings align with global evidence linking arsenic exposure to skin lesions, cardiovascular problems and increased risk of chronic diseases14,15,17,44,46, while also reinforcing the heightened susceptibility of children to such contaminants. The persistence of arsenic exceedances highlights the chronic nature of exposure, pointing to a combination of natural geogenic sources and anthropogenic inputs in the Betwa-Yamuna system. Without targeted monitoring and treatment, the risks identified here suggest long-term health issues for communities reliant on river water for drinking and domestic use. Seasonally, the highest HQ values occurred during the pre-monsoon low-flow period, while monsoon months consistently showed the lowest risk levels, confirming strong hydrological control on exposure intensity.

Hazard index

Table 9 shows cumulative HI values by site and season, and Fig. 4 summarises their distributions for adults and children. The data show that cumulative, non-carcinogenic risk is site- and season-dependent. For adults, HI medians were well below 1.0 at the Betwa River across all seasons (median 0.19–0.39), but approached or exceeded unity at the Yamuna River and the confluence during pre-monsoon (Yamuna median 1.05; confluence median 1.45). For children, HI medians were consistently > 1.0 at Yamuna (1.28–2.44) and the confluence (1.64–3.38) in every season, while Betwa remained < 1.0 (0.44–0.92). These patterns indicate that cumulative exposures are most severe where upstream inputs converge and during seasons of reduced flow, when concentration effects are strongest.

The dominance of the Yamuna and confluence sites in driving HI exceedances reflects the additive contributions of multiple metals rather than a single contaminant. Although arsenic is the most consistent driver of high HQs, higher values for Fe and Mn also contribute to seasonal spikes in HI, particularly under pre-monsoon and winter low-flow conditions. Figure 4 shows that children’s HI values are typically about twofold higher than adults’ at the same site/season, e.g. confluence pre-monsoon: adult mean 1.43 vs child mean 3.34, highlighting disproportionate vulnerability. The persistence of HI > 1 for children at the Yamuna and confluence throughout the year suggests a chronic exposure risk that cannot be attributed to episodic pulses alone.

The high and persistent HI values show that people who use untreated river water face serious health risks from multiple metals at the same time. For children, HI values of 2 or more in several seasons mean the risks are even greater because contaminants add up. Unlike single-metal HQs, the HI highlights the full risk of exposure and shows that overall risk is much higher. The cumulative risk expression followed the same seasonal structure, with maximum HI during pre-monsoon, minimum values during monsoon dilution, and partial risk recovery during post-monsoon conditions. These results point to the need for targeted action at the Yamuna and confluence sites, especially in the pre-monsoon and winter months, and for special protection of children through focused monitoring and treatment strategies.

Carcinogenic risk assessment

Carcinogenic risks were estimated for As, Cd and Pb, which are recognised for their carcinogenic potential through oral pathways2,40,54 (Table 10). The results show that As is the dominant contributor, with adult CR values reaching a median of 8.1 × 10⁻5 and peaking at 2.1 × 10⁻4, thereby exceeding the USEPA benchmark of 1 × 10⁻4 in the upper distribution5,35,36,37,55. For children, the median CR was slightly lower at 3.8 × 10⁻5, but the 95th percentile (8.8 × 10⁻5) and maximum (9.6 × 10⁻5) approach the threshold, highlighting their heightened vulnerability. By contrast, Cd and Pb remained well below the threshold, with maximum values on the order of 10⁻⁶, suggesting that these metals are unlikely to pose significant carcinogenic risks in this system. The systematic decline in metal concentrations and associated HQ, HI, and CR values during the monsoon reflects dilution by high rainfall and increased river discharge, which temporarily reduces contaminant residence time and exposure potential. Arsenic-driven carcinogenic risk peaked during the pre-monsoon and early winter months, whereas monsoon conditions consistently suppressed CR values through hydrological dilution. However, the metal concentration presence signals the need for continued vigilance, especially during low flow months when pollutant concentrations are high. These findings indicate that long-term arsenic exposure presents a chronic cancer risk in the Betwa-Yamuna system, consistent with widespread concerns across South Asia, where as contamination has been linked to increased cancer concerns.

Monte Carlo simulation

Probability distributions

Monte Carlo simulations (10,000 runs) were performed to quantify uncertainty in HQ, HI and CR using empirical (bootstrap) sampling of measured concentrations and variability in exposure factors. Probability density functions for HI are shown in Fig. 5, and percentile summaries for HQ (per metal), HI and CR (As) are reported in Table 11. The children’s HI distribution is right-skewed with a longer tail than adults, confirming greater upper-end risk even when central tendencies are comparable. Consistent with deterministic findings, arsenic dominates carcinogenic risk: the simulated P95 for CR(As) exceeds 1 × 10⁻4 in adults and approaches the benchmark in children, indicating that high exposure scenarios are possible and policy relevant.

Cumulative exceedance probability

Cumulative exceedance curves (Fig. 6) and exceedance summaries (Table 12) provide threshold-focused insights. Simulations indicate HI > 1 in roughly 62–69% of children’s runs and ~ 20–23% of adults’ runs, highlighting both higher central risk and more frequent threshold exceedance in children. For carcinogenic risk, CR(As) shows the highest exceedance probabilities, with children again more vulnerable. Probabilistic outcomes preserved the same seasonal hierarchy observed in deterministic results, with pre-monsoon showing the highest likelihood of exceedance, monsoon the lowest, and post-monsoon transitional behaviour.

Comparative risk between adults and children

Comparative bar plots (Fig. 7) highlight clear and systematic differences between adults and children in both non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks. For non-carcinogenic exposure, children consistently exhibit higher hazard quotients than adults, with median HQ values for As and Pb typically 1.5–2 times higher in children. This difference propagates into the cumulative Hazard Index (HI), where children’s median HI values exceed adult values by a similar factor across seasons. This amplified risk is primarily driven by children’s higher intake-to-body-weight ratio and shorter non-carcinogenic averaging time (AT = ED × 365), which increases effective dose relative to body mass. These results quantitatively confirm that children are the most vulnerable group for cumulative, multi-metal exposure in the Betwa–Yamuna system.

In contrast, arsenic-related carcinogenic risk (CR) is systematically higher in adults than in children, with adult median and upper-percentile CR values exceeding those of children by approximately 2–3 times under the adopted exposure assumptions. This occurs because the cancer averaging time is fixed at 70 years for both groups, while adults experience longer exposure duration and higher ingestion rates, which together outweigh body-mass differences. This dual pattern indicates that children bear the dominant burden of cumulative non-carcinogenic effects (HI), whereas adults carry the larger lifetime cancer risk from arsenic (CR). From a management perspective, child-focused protection should prioritise reducing multi-metal exposure through household and community-scale treatment, while adult risk mitigation should focus specifically on arsenic source control, adsorption-based removal, and routine seasonal monitoring, particularly during low-flow periods.

Discussion

Trace element contamination in the Betwa–Yamuna river system reflects the combined influence of geogenic weathering processes and diverse anthropogenic inputs such as agriculture, thermal power generation, urban sewage, and industrial effluents56,57,58,59. The frequent exceedance of WHO standards for As at the confluence and downstream Yamuna sites highlights cumulative upstream loading and enhanced mobilisation under mixing conditions. The amplified contaminant levels and health risks at the confluence are consistent with cumulative upstream loading and hydraulic mixing of two chemically contrasting river systems, which enhances both metal mobilization and exposure potential. Arsenic concentrations repeatedly exceeded the 0.01 mg/L guideline, consistent with documented arsenic-related cancer and cardiovascular risks across South Asia16,41,42. Lead contamination, previously reported upstream near Delhi60, likely originates from industrial discharges, vehicular emissions, and agricultural inputs. Although Cd and Pb exceedances were less frequent, even low-level exposure is concerning due to their cumulative nephrotoxic and skeletal impacts3,4,12. Elevated metal levels during pre-monsoon and winter further indicate the concentrating effect of low-flow conditions.

Non-carcinogenic risk metrics (HQ and HI) demonstrate a clear age-dependent vulnerability pattern. Children consistently exhibited HI values exceeding 1.0 across all seasons, while adult risks approached or exceeded unity mainly during low-flow periods. These findings align with observations from contaminated river basins in Egypt and China, where higher intake-to-body-weight ratios drive elevated child risk1,39,61. HI values above 2.0 in several months confirm the importance of multi-metal cumulative exposure assessment rather than reliance on single-contaminant indicators. Carcinogenic risk analysis further identifies As as the dominant driver, with more than 40% of samples exceeding the USEPA benchmark of 1 × 10⁻435,37. Monte Carlo simulations strengthen these findings by revealing a markedly higher probability of unsafe HI exceedance for children (~ 67%) compared to adults (~ 23%), while As also shows the highest likelihood of carcinogenic exceedance. Together, these results support the urgent need for seasonal monitoring, stricter regulation of point and non-point pollution sources, and deployment of community-level treatment technologies to protect public health and advance Sustainable Development Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation)62,63.

Conclusion and recommendations

This study demonstrates that the Betwa–Yamuna confluence is affected by significant water quality degradation, with As persistently exceeding WHO drinking-water guidelines and driving both non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic health risks. Seasonal controls exerted a strong influence on contaminant behaviour, with the highest metal concentrations occurring during pre-monsoon and winter low-flow periods, when dilution capacity is reduced. The HI consistently exceeded the safety threshold (HI > 1) for children in all seasons, while adults showed frequent exceedances during low-flow months, confirming the presence of chronic multi-metal exposure risks. Carcinogenic risk assessment further identified As as the dominant contributor, with a substantial proportion of exposures exceeding the USEPA acceptable cancer risk level. Monte Carlo simulations strengthened these findings by demonstrating wide uncertainty ranges and long-tailed probability distributions, particularly for children, confirming their heightened vulnerability under realistic exposure scenarios. These results collectively show that untreated river water at this confluence presents a persistent and seasonally amplified public-health concern.

Despite the robustness of the dataset and analytical framework, this study has certain limitations. The assessment was based on surface-water concentrations only, and thus does not account for groundwater–surface water interactions, which may influence exposure in adjacent communities. In addition, site-specific exposure parameters were not available, requiring reliance on WHO/USEPA default values, which may introduce uncertainty in absolute risk magnitudes. Furthermore, metals were evaluated as total concentrations, without accounting for speciation or bioavailability, which can influence toxicity. Recent studies increasingly emphasize the importance of coupling surface water, groundwater, and biomonitoring data and integrating real-time sensors and isotope-based tracers to resolve contaminant transport pathways more accurately. Future investigations should therefore include multi-pathway exposure routes, site-specific demographic data, and longer monitoring periods to better quantify chronic exposure dynamics.

From a management perspective, the findings clearly indicate the need for priority control of As, Pb, and Cd at the Betwa–Yamuna confluence. Seasonally resolved monitoring programs should be institutionalized to capture low-flow risk amplification. Community-scale water treatment systems, e.g. adsorption-based filtration, coagulation–flocculation, membrane processes, and decentralized treatment units, are urgently required in settlements dependent on untreated water. Pollution source control, targeting industrial effluents, municipal wastewater discharges, and agricultural runoff, must be enforced simultaneously. Public awareness campaigns and child-focused protection strategies are essential, given the consistently elevated health risks observed in children. These recommendations align directly with Sustainable Development Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and support recent international frameworks advocating risk-based water governance rather than concentration-only compliance monitoring. This study therefore provides a critical health-risk baseline for northern Indian river confluences and offers a scientifically rigorous platform for evidence-driven water safety policy and long-term mitigation planning.

Data availability

The data is available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Pan, S. et al. Effects of lead, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury co-exposure on children’s intelligence quotient in an industrialized area of southern China. Environ. Pollut. 235, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.044 (2018).

Nag, R. & Cummins, E. Human health risk assessment of lead (Pb) through the environmental-food pathway. Sci. Tot. Environ. 810, 151168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151168 (2022).

Johri, N., Jacquillet, G. & Unwin, R. Heavy metal poisoning: The effects of cadmium on the kidney. Biometals 23, 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10534-010-9328-y (2010).

Satarug, S. C., Gobe, G. A., Vesey, D. & Phelps, K. R. Cadmium and lead exposure, nephrotoxicity, and mortality. Toxics 8, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics8040086 (2020).

Budi, H. S. et al. Source, toxicity and carcinogenic health risk assessment of heavy metals. Rev. Environ. Health 39, 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2022-0096 (2024).

Fu, F. & Wang, Q. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 92, 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.011 (2011).

Mavakala, B. K. et al. Leachates draining from controlled municipal solid waste landfill: Detailed geochemical characterization and toxicity tests. Waste Manag. 55, 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.04.028 (2016).

Suthar, S., Sharma, J., Chabukdhara, M. & Nema, A. K. Water quality assessment of river Hindon at Ghaziabad, India: Impact of industrial and urban wastewater. Environ. Monit. Assess. 165, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-009-0930-9 (2010).

Parde, D. & Behera, M. in Sustainable Industrial Wastewater Treatment and Pollution Control (ed Maulin P. Shah) 229–255 (Springer, 2023).https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-2560-5_12

Gaur, N. et al. Evaluation of water quality index and geochemical characteristics of surfacewater from Tawang India. Sci. Rep. 12, 11698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14760-3 (2022).

Agnihotri, S. K. & Kesari, K. K. in Networking of Mutagens in Environmental Toxicology (ed Kavindra Kumar Kesari) 25–47 (Springer International Publishing, 2019).https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96511-6_2

Goyer, R. A. Mechanisms of lead and cadmium nephrotoxicity. Toxicol. Let. 46, 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4274(89)90124-0 (1989).

Gunduz, O. et al. The health risk associated with chronic diseases in villages with high arsenic levels in drinking water supplies. Expo. Health 9, 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12403-016-0238-2 (2017).

Yoshida, T., Yamauchi, H. & Fan Sun, G. Chronic health effects in people exposed to arsenic via the drinking water: Dose–response relationships in review. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 198, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2003.10.022 (2004).

Rahman, M. M., Ng, J. C. & Naidu, R. Chronic exposure of arsenic via drinking water and its adverse health impacts on humans. Environ. Geochem. Health 31, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-008-9235-0 (2009).

Palit, S., Misra, K. & Mishra, J. in Separation Science and Technology Vol. 11 (ed Satinder Ahuja) 113–123 (Academic Press, 2019).https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815730-5.00005-3

Moon, K., Guallar, E. & Navas-Acien, A. Arsenic exposure and cardiovascular disease: An updated systematic review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 14, 542–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-012-0280-x (2012).

Yuan, S.-Y., Xu, L., Tang, H.-W., Xiao, Y. & Gualtieri, C. The dynamics of river confluences and their effects on the ecology of aquatic environment: A review. J. Hydrodyn. 34, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42241-022-0001-z (2022).

Constantinescu, G. & Gualtieri, C. River confluences: A review of recent field and numerical studies. Environ. Fluid Mech. 24, 1143–1191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10652-024-10002-4 (2024).

Bender, J., Wahl, T., Müller, A. & Jensen, J. A multivariate design framework for river confluences. Hydrol. Sci. J. 61, 471–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2015.1052816 (2016).

Girija, T. R., Mahanta, C. & Chandramouli, V. Water quality assessment of an untreated effluent impacted urban stream: The Bharalu tributary of the Brahmaputra River India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 130, 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-006-9391-6 (2007).

Sharma, M. et al. The state of the Yamuna River: A detailed review of water quality assessment across the entire course in India. Appl. Water Sci. 14, 175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-024-02227-x (2024).

Rai, S. P., Noble, J., Singh, D., Rawat, Y. S. & Kumar, B. Spatiotemporal variability in stable isotopes of the Ganga River and factors affecting their distributions. CATENA 204, 105360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105360 (2021).

Kirkels, F. M. S. A., Zwart, H. M., Basu, S., Usman, M. O. & Peterse, F. Seasonal and spatial variability in δ18O and δD values in waters of the Godavari River basin: Insights into hydrological processes. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 30, 100706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2020.100706 (2020).

Bhattacharya, S. K., Gupta, S. K. & Krishnamurthy, R. V. Oxygen and hydrogen isotopic ratios in groundwaters and river waters from India. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Earth Planet Sci.) 94, 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02839206 (1985).

Lambs, L., Balakrishna, K., Brunet, F. & Probst, J.-L. Oxygen and hydrogen isotopic composition of major Indian rivers: A first global assessment. Hydrol. Process. Int. J. 19, 3345–3355. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.5974 (2005).

Chetia, M. et al. Groundwater arsenic contamination in Brahmaputra river basin: A water quality assessment in Golaghat (Assam) India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 173, 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-010-1393-8 (2011).

Akiner, M. E., Chauhan, P. & Singh, S. K. Evaluation of surface water quality in the Betwa river basin through the water quality index model and multivariate statistical techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 31, 18871–18886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-024-32130-6 (2024).

Singh, S., Jain, V. & Goyal, M. K. Evaluating climate shifts and drought regions in the central Indian river basins. Sci. Rep. 15, 29701. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15231-1 (2025).

Palmate, S. S., Pandey, A., Kumar, D., Pandey, R. P. & Mishra, S. K. Climate change impact on forest cover and vegetation in Betwa Basin India. Appl. Water Sci. 7, 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-014-0222-6 (2017).

Maansi, J. & R. & Wats, M.,. Evaluation of surface water quality using water quality indices (WQIs) in Lake Sukhna, Chandigarh. India. Appl. Water Sci. 12, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-021-01534-x (2021).

Singh, P. et al. Assessment of ground and surface water quality along the river Varuna, Varanasi India. Environ. Monit. Assess. 187, 170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-015-4382-0 (2015).

Brindha, K. & Kavitha, R. Hydrochemical assessment of surface water and groundwater quality along Uyyakondan channel, south India. Environ. Earth Sci. 73, 5383–5393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-014-3793-5 (2015).

Sahoo, M. M. & Swain, J. B. Modified heavy metal pollution index (m-HPI) for surface water quality in river basins India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 15350–15364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-08071-1 (2020).

World Health Organization. Guidelines for drinking-water quality. 4th edn, Vol. 1 (World Health Organization, 2022)

Wiltse, J. & Dellarco, V. L. U. S. Environmental protection agency guidelines for carcinogen risk assessment: Past and future. Mutation Res./Rev. Genetic Toxicol. 365, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1110(96)90009-3 (1996).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Guidelines for carcinogen risk assessment. Report No. 7/02/99, (United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington D.C., 1999).

Mikhaĭlov, G. & Medvedev, I. y. N. Optimization of weighted monte carlo methods with respect to auxiliary variables. Sib. Math. J. 45 (2004).

Eid, M. H. et al. Comprehensive approach integrating water quality index and toxic element analysis for environmental and health risk assessment enhanced by simulation techniques. Environ. Geochem. Health 46, 409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-024-02182-1 (2024).

Gupta, S. & Gupta, S. K. Application of Monte Carlo simulation for carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks assessment through multi-exposure pathways of heavy metals of river water and sediment India. Environ. Geochem. Health 45, 3465–3486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-022-01421-7 (2023).

Brammer, H. & Ravenscroft, P. Arsenic in groundwater: A threat to sustainable agriculture in South and South-east Asia. Environ. Int. 35, 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.10.004 (2009).

Benner, S. G. & Fendorf, S. Arsenic in south Asia groundwater. Geogr. Compass 4, 1532–1552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00387.x (2010).

Stanger, G. A palaeo-hydrogeological model for arsenic contamination in southern and south-east Asia. Environ. Geochem. Health 27, 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10653-005-7102-9 (2005).

Wang, C.-H. et al. A review of the epidemiologic literature on the role of environmental arsenic exposure and cardiovascular diseases. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 222, 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2006.12.022 (2007).

APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater (American Public Health Association). (American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation, 2012)

Chen, Y. et al. Arsenic exposure at low-to-moderate levels and skin lesions, arsenic metabolism, neurological functions, and biomarkers for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases: Review of recent findings from the health effects of arsenic longitudinal study (HEALS) in Bangladesh. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 239, 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2009.01.010 (2009).

Bureau of Indian Standards. BIS: IS 10500:2012. (Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2012).

Guo, W. & Xu, T. in Mathematical Modelling and Numerical Simulation of Oil Pollution Problems (ed Matthias Ehrhardt) 127–140 (Springer, 2015).https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16459-5_6

Verma, S. & Sinha, A. Appraisal of groundwater arsenic on opposite banks of River Ganges, West Bengal, India, and quantification of cancer risk using Monte Carlo simulations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 25205–25225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17902-8 (2023).

Rehman, K., Fatima, F., Waheed, I. & Akash, M. S. H. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. J. Cell. Biochem. 119, 157–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.26234 (2018).

Corwin, D. L. & Yemoto, K. Salinity: Electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 84, 1442–1461. https://doi.org/10.1002/saj2.20154 (2020).

Williams, M. et al. Emerging contaminants in a river receiving untreated wastewater from an Indian urban centre. Sci. Tot. Environ. 647, 1256–1265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.084 (2019).

Laskar, A. H., Bhattacharya, S. K., Rao, D. K., Jani, R. A. & Gandhi, N. Seasonal variation in stable isotope compositions of waters from a Himalayan river: Estimation of glacier melt contribution. Hydrologic. Process. 32, 3866–3880. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13295 (2018).

Li, H.-B. et al. Oral bioavailability of As, Pb, and Cd in contaminated soils, dust, and foods based on animal bioassays: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 10545–10559. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b03567 (2019).

Albert, R. E. Carcinogen risk assessment in the U.S. environmental protection agency. Critical Rev. Toxicol. 24, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408449409017920 (1994).

Gaillardet, J., Viers, J. & Dupré, B. in Treatise on geochemistry: second edition Vol. 7 (ed J.I. Drever) 195–235 (2013).https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.00507-6

Salati, S. & Moore, F. Assessment of heavy metal concentration in the Khoshk River water and sediment, Shiraz Southwest Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 164, 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-009-0920-y (2010).

Dubey, C. S. et al. Anthropogenic arsenic menace in Delhi Yamuna flood plains. Environ. Earth Sci. 65, 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-011-1072-2 (2012).

Osuna-Martínez, C. C., Armienta, M. A., Bergés-Tiznado, M. E. & Páez-Osuna, F. Arsenic in waters, soils, sediments, and biota from Mexico: An environmental review. Sci. Total Environ. 752, 142062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142062 (2021).

Sankhla, M. S., Kumar, R. & Prasad, L. Variation of chromium concentration in Yamuna River (Delhi) water due to change in temperature and humidity. J. Seybold Rep. 15, 293–299 (2020).

Elgendy, A. R., El Daba, A. E. M. S., El-Sawy, M. A., Alprol, A. E. & Zaghloul, G. Y. A comparative study of the risk assessment and heavy metal contamination of coastal sediments in the Red sea, Egypt, between the cities of El-Quseir and Safaga. Geochem. Trans. 25, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12932-024-00086-8 (2024).

Sadoff, C. W., Borgomeo, E. & Uhlenbrook, S. Rethinking water for SDG 6. Nat. Sustain. 3, 346–347. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0530-9 (2020).

Carlsen, L. & Bruggemann, R. The 17 United Nations’ sustainable development goals: A status by 2020. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecology 29, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2021.1948456 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Director, Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), Lucknow, India for necessary facilities for carrying out this research work. We are thankful to the technical staff of the BSIP for their assistance in processing the samples. The present manuscript is the outcome of the BSIP in-house Quaternary Lake drilling Project (BSIP/RDCC/90/25-26). The authors are thankful to all the help obtained during the sampling and analysis throughout the project from the project members. Thanks are also due to local villagers of all the sampling sites for their help.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Data Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Data Curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing: **P.K**; Data Curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—review & editing: **AMS**; Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing—review & editing: **AS, AT and R.R**; Software, Data Modelling, Data Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—original: **K.S.M** . The authors declare their consent to publish the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors have reviewed and approved the submission and publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prasanna, K., Amal, M.S., More, K.S. et al. Human health implications of metal pollution in the Betwa-Yamuna river system, India: evidence from Monte Carlo risk modelling. Sci Rep 16, 5058 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34780-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34780-z