Abstract

A Lyapunov-stability-guaranteed local model adaptive RBF neural network control algorithm is proposed for industrial robots. This algorithm eliminates the need for an exact plant mathematical model, enabling real-time learning and compensation of system nonlinearities and uncertainties. An adaptive control law adjusts neural network parameters online to achieve high-precision tracking control of robot manipulators. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is employed to optimize the RBF basis width parameters. Validation was performed using the ABB IRB1600 industrial robot, modeled and simulated in MATLAB Simscape. Real-time trajectory tracking was demonstrated, with ADAMS co-simulation used for further verification. Results demonstrate the algorithm’s effectiveness in reducing tracking errors and enhancing robustness and adaptability, while maintaining stability within the Lyapunov framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Industrial robots play a crucial role in modern manufacturing by enhancing production efficiency, reducing labor costs, and improving product quality and consistency. They operate in challenging environments to ensure worker safety. However, their control technology faces various challenges such as achieving precise positioning, enhancing intelligence, adapting to complex scenarios, and ensuring safety and reliability. These challenges necessitate continuous technological innovation to fully unleash the potential of industrial robots and drive the industry towards more efficient, intelligent, and safe development.

In the realm of robot control, traditional methods encompass strategies based on classical or modern control theories, widely applied in robotics and automatic control domains. PID control, a prevalent traditional method, calculates the control signal based on proportional, integral, and derivative components of the error, allowing for straightforward implementation and suitability for linear or approximately linear systems.

Sliding Mode Control (SMC) stands out as a distinctive nonlinear method enabling robust system control through a designed control law that ensures state sliding on a designated surface. While SMC demonstrates robustness to parameter variations and external disturbances, it may encounter chattering issues, often mitigated through the use of saturation functions. Model Predictive Control (MPC) represents a model-based optimization approach predicting future system behavior based on current states and the prediction model. By solving an optimization problem, MPC generates optimal control inputs, offering the capability to handle multiple variables, constraints, and uncertainties. However, MPC’s computational intensity and high hardware requirements pose notable considerations. Linear control is grounded on the linear model of the system, with controllers like state feedback controllers and output feedback controllers tailored for this purpose. It is assumed in linear control methods that the system’s dynamic behavior is linear or can be approximated through linearization. On the other hand, inverse dynamic control is rooted in the robot’s dynamics model, employing robot dynamics equations to compute necessary joint torques or forces for achieving desired motion. These calculated values are used as control inputs to drive the robot’s motion effectively, benefiting from the robot’s dynamic characteristics to enhance control accuracy and efficiency.

Numerous scholars have extensively researched and discussed these concepts. Mojtaba Ahmadieh Khanesar1 proposed an industrial robot control method using static and nearly static speed sliding mode fuzzy control. Joint angles are obtained from Cartesian coordinates using the extended Kalman filter. A sliding mode fuzzy controller is then applied to control the robot dynamics. The control algorithm is tested on UR5. Thanh Nguyen Truong2 investigated the neural network-based SMC for robotic manipulation, discussing technical challenges, applications, and future prospects. Yong Gao3 studied the trajectory tracking problem of upper limb rehabilitation robot using model predictive control, establishing a pseudo-linearized extended state space model and designing a model predictive controller based on Laguerre model to reduce computational complexity. The stability of the controller was proven, and a disturbance observer was introduced for compensation. Joint space sliding mode variable was utilized for synchronous tracking. Y Xu4 proposed a robust sliding mode control law for industrial robots, combining linear sliding mode manifold and double power reaching law based on Udwadia-Kalaba theory to address flexibility, load changes, and unknown disturbances. Dongliang Wang5 proposed a Sliding Mode Observer-based Model Predictive Tracking Control for Mecanum-wheeled mobile robot. The method addresses trajectory tracking in the presence of disturbances and uncertainties. It involves a model predictive controller based on Adaptive Variable Power sliding mode Observer (AVPSMO-MPC) to handle physical constraints, solve optimal control input online, and design a feedforward compensation controller for disturbance and uncertainty suppression during robot movement. The stability of AVPSMO is demonstrated using Lyapunov theory. Teng Zhang6 discuss the challenges faced by space robots, such as modeling uncertainty, measurement noise, and large sampling interval, which can impact tracking performance and control safety. They propose a robust adaptive trajectory tracking method for space manipulators, integrating extended Kalman filtering, high-order disturbance observer, and discrete nonsingular terminal sliding mode control techniques. The method enhances state estimation accuracy by introducing auxiliary variables into the filter and designs an improved terminal sliding mode controller based on equivalent control to ensure tracking stability and mitigate adverse effects of long sampling times. David Cruz-Ortiz7 proposed an adaptive controller for trajectory tracking in master-slave robot systems. The controller is based on sliding mode theory and considers state constraints using state-dependent adaptive gains. The design ensures finite-time convergence and asymptotic convergence of the tracking error through Lyapunov stability analysis.

Traditional control methods have demonstrated significant success in practical applications. However, achieving optimal control effects for complex systems like multi-joint industrial robots, characterized by high non-linearity, strong coupling, and uncertainty, remains challenging. Scholars are actively exploring the integration of traditional control algorithms with neural networks to enhance control performance. This approach involves dividing the control model into precise and imprecise components, with neural networks employed to compensate for inaccuracies.

Zahra8 proposed a PSO-optimized RBFNN and STSMC hybrid control scheme for 2-degree-of-freedom robotic arm path tracking. STSMC suppresses jitter and ensures finite-time convergence, RBFNN estimates the system nonlinearity, and PSO optimizes key parameters to minimize tracking errors. Through Lyapunov stability analysis and simulation verification, this scheme reduces tracking errors compared to traditional SMC, but it has limitations such as modular design resulting in insufficient coupling between adaptive learning and stability mechanisms, failure to consider control energy efficiency, and verification limited to low-degree-of-freedom systems. Arents J9 believes that robotic systems with artificial intelligence are strongly emerging as one of the main areas of concern, as flexibility and a deep understanding of complex manufacturing processes are emerging as key advantages to increase competitiveness. Zhihao Liu10 believes that imitation learning, policy gradient learning, value function learning, actor-critic learning and model-based learning are the four mainstream techniques of robot learning. For robots that do not have open torque or voltage interfaces, GULAM DASTAGIR KHAN11 introduced a framework that is independent of the dynamics, internal controller configuration, and control gain structure of the robot, using adaptive neural networks to address the challenges of controlling closed-structure industrial manipulators. Zeqi Yang12 proposed an adaptive neural network force-tracking impedance control scheme based on nonlinear observer for robotic systems with uncertainties and external disturbances. Jiabin Hu13 proposed a neural network-based second-order sliding mode control method for trajectory tracking of manipulators with dynamic uncertainties, external disturbances, and input saturation. In this paper, a new fuzzy wavelet neural network (FWNN) is designed to estimate these unknown uncertainties by combining these unknown uncertainties into a composite uncertainty. Fuli Zhang14 used fuzzy neural network sliding mode control and designed the rigid subsystem controller to suppress the system jitter caused by parameter mutation. The robust tracking of space robot trajectory is realized. At the same time, a weighted average fuzzy controller is designed to control the deformation of the link. MATLABand ADAMS are also used to validate the dynamic IC and control model. Qiong Liu15 introduced two adaptive bias Radial Basis Function Neural Network (RBFNN) control strategies, namely the local bias scheme and global bias scheme, to address the bias in manipulator dynamics equations affected by gravity and constant load. These schemes aim to mitigate the adverse impact of bias and enhance the approximation accuracy of RBFNN for dynamics with significant deviations, consequently enhancing control performance. Additionally, the authors utilized Lyapunov stability theory to demonstrate the uniform ultimate boundedness of the closed-loop system. Xinle Yan16 studied adaptive and intelligent control of a dual-arm space robot for target manipulation after capture. They used two manipulators, developed a system model considering closed-loop constraints, and proposed self-tuning control strategy (STC) and Radial basis function neural network control strategy (RBF) for trajectory tracking. Simulation and experimental results demonstrated the superiority of RBF and STC strategies in terms of control accuracy and robustness, with RBF showing better control accuracy and STC being more energy efficient than traditional Computational torque control (CTC) strategy. Ningyu Zhu17 proposed a method for visual servoing of a 6-RSS parallel robot using adaptive sliding mode control. A robust sliding mode controller was designed to handle system uncertainty, and an RBF neural network was employed for self-tuning control gain to enable effective trajectory tracking under time-varying conditions. To enhance excavator performance, Hao Feng18 proposed an adaptive sliding mode control method based on RBF neural network (SMC-RBF). The RBF neural network is used to approximate and compensate the model uncertainties and load disturbances of the electro-hydraulic servo system. An adaptive mechanism is designed to adjust the connection weights of RBF neural network in real time to ensure the stability of the network. Pei Jiang19 proposed a data-driven approach using LSTM to predict and optimize energy consumption of industrial robots when dynamic and electrical parameters are unavailable due to commercial constraints. They analyzed the causal relationship between robot EC and joint motion variables, such as position, velocity, and acceleration, considering the drive system’s capacitance and sensing element influence. Their deep neural network based on LSTM can predict EC without requiring specific robot parameters.

XU Zheng20 addressed the issue of significant errors in predicted torque of collaborative robots by utilizing a deep recurrent neural network with a long short-term memory model. The study focused on compensating for errors in the dynamics model of a self-developed 6-DOF collaborative robot, considering various forces. The experiment involved using an optimized excitation trajectory based on Fourier series for robot motion, estimating joint torque using motor current, and training a Long Short-Term Memory Model (LSTM) compensation network with original data. The network’s training results were evaluated based on the root mean square error of predicted torque compared to actual torque. Both the computational and experimental outcomes demonstrated improved predictive accuracy of the compensated dynamic model for the collaborative robot’s torque. Sichao Liu21 developed accurate dynamic models of the robot in pre-sliding and sliding states to estimate external forces/torques, while also exploring friction models. Adaptive admittance control is used to support human-machine collaborative assembly, which naturally and easily achieves precise positioning and smooth motion control. Yu X22 proposed an adaptive impedance trajectory tracking control strategy based on neural networks to compensate for uncertainties in robot dynamics. This method realizes the motion synchronization of human-robot, achieves stable and efficient interaction behavior, and reduces the control workload of humans. Alejandra Hernandez-Sanchez23 summarized a comprehensive technical design of an adaptive state feedback controller for a multi-link manipulator aiming at the influence of position and velocity constraints on the tracking trajectory control method. The sufficient condition based on the Riccati equation simplifies the implementation of the adaptive controller. Sai24 provides useful references for the application of RBFNN in robotic arm control, but its framework still has three aspects that need to be improved: Firstly, it adopts a modular design, but does not incorporate local approximation and adaptive learning processes into a unified stability analysis framework, lacking an integrated guarantee for the stability of the closed-loop system; Secondly, by optimizing all hyperparameters through EPSO, it does not consider control energy efficiency, and static parameter optimization is difficult to adapt to the time-varying nonlinear characteristics of industrial scenarios; Thirdly, the verification object does not focus on industrial-grade robotic arms, and does not provide parameter tuning criteria that can directly guide engineering applications.

Some existing model-based approaches may require precise dynamic models, increasing algorithmic complexity. In certain scenarios, this can lead to extended response times or robustness challenges under specific disturbances. By contrast, this paper proposes an adaptive RBF neural network control strategy based on local model approximation. The proposed strategy reduces dependency on precise prior model knowledge. In simulation studies, it achieves improved tracking accuracy and maintains stability under tested disturbances. The effectiveness of the algorithm is demonstrated through tracking control experiments conducted on the ABB IRB1600 manipulator.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Designing and synthesizing an adaptive controller that effectively combines local model approximation via RBF networks, Lyapunov-based adaptive laws, and sliding mode control. The key engineering challenge of ensuring closed-loop stability within this combination is formally addressed.

-

(2)

Employing Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) specifically for the critical yet often empirically-tuned basis width parameters of the RBF networks, enhancing model approximation capability in a reproducible manner.

-

(3)

The proposed framework is rigorously evaluated through high-fidelity, cross-validated simulations (MATLAB/Simscape and ADAMS), demonstrating its advantages in tracking accuracy and robustness over conventional methods like SMC-PID under tested uncertainties.

Control strategy design

RBF neural network theory

An RBF neural network comprises an input layer, a hidden layer utilizing radial basis functions, and an output layer for generating control signals. Radial basis functions like Gaussian functions and multi-aperture functions are commonly employed to capture local characteristics of input signals.

The RBF neural network demonstrates robust nonlinear approximation capabilities, making it suitable for addressing complex control problems effectively. It is characterized by a three-layer feed-forward structure consisting of an input layer, a hidden layer with radial basis functions as activation functions, and an output layer. This network offers rapid learning speed, high approximation accuracy, and excellent generalization abilities. Its applications span function approximation, pattern recognition, signal processing, and other domains, with the added advantage of fast training suitable for real-time control scenarios. Furthermore, its ease of implementation and adjustment without complicated mathematical derivations contribute to its practical appeal.

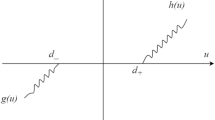

The RBF network structure with three hidden layers is shown in Fig. 1.

In RBF network, \({\mathbf{x}}={\left[ {{x_i}} \right]^T}\) is the input of the network, and the output of the hidden layer of the network is \({\mathbf{h}}={\left[ {{{\text{h}}_{\text{j}}}} \right]^T}\). \({{\text{h}}_{\text{j}}}\) is the output of the first neuron in the hidden layer.

Where\({\mathbf{c}}=\left[ {{c_{ij}}} \right]=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{c_{11}}}& \cdots &{{c_{1m}}} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {{c_{n1}}}& \cdots &{{c_{nm}}} \end{array}} \right]\) is the coordinate vector of the center point of the Gaussian basis function of the j-th neuron in the hidden layer, \(i=1,2, \cdots n,j=1,2, \cdots m;{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\mathbf{b}}={\left[ {{b_1}, \cdots ,{b_m}} \right]^T}\), \({b_j}\)is the width of the Gaussian basis function of the j-th neuron in the hidden layer.

The weights of RBF network are:

The output is:

The RBF neural network training process comprises two key stages: offline training and online tuning. During the offline training phase, the focus lies on establishing the position and scope of the hidden layer neurons. This stage also involves refining the connection weights between the hidden layer and the output layer by minimizing the error function. On the other hand, in the online adjustment stage, real-time weight adjustments are made to the output layer to precisely meet the specific control needs.

Research on adaptive neural network algorithm with local model approximation

Accurate mathematical modeling of industrial robot control systems is challenging due to their complexity, nonlinearity, and time-varying dynamics. The local model approximation is a control strategy that does not require prior knowledge of the precise mathematical model of the controlled object. By utilizing input and output data from the robot dynamic system or employing techniques such as neural networks and fuzzy logic to approximate system dynamics, effective control can be achieved. Combining local model approximation with RBF neural network enables high-precision tracking control of manipulators.

In the context of local model approximation, the RBF neural network is employed to approximate the dynamic characteristics of the manipulator system. The joint angle and angular velocity serve as inputs to the RBF neural network, while the joint torque is the output. Through training the network, the forward and inverse dynamics models of the manipulator are approximated. Consequently, the RBF neural network model can predict the joint torques required for the desired motion without the need for precise knowledge of the robot’s inertial parameters.

To enhance control accuracy and performance, the parameters of the RBF neural network are optimized. A combination of sliding mode control and adaptive control is then applied to further improve the system’s control effectiveness. An adaptive law is developed to adjust the RBF neural network parameters in real-time. The sliding mode surface is designed based on the stability and tracking capabilities of the manipulator system. Subsequently, a sliding mode control law is formulated using the sliding mode surface and the output of the RBF neural network. This control law ensures the system state remains on the sliding mode surface, effectively suppressing chattering phenomena.

Problem description

Consider dynamic equation of n- link manipulator as.

Where,\({\mathbf{M}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)is the order\(n \times n\)positive definite inertia matrix,\({\mathbf{C}}\left( {{\mathbf{q,\dot {q}}}} \right)\)is the order\(n \times n\)inertia matrix, is the centrifugal and Coriolan force term,\({\mathbf{G}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)is the order\(n \times 1\)inertia vector,\({{\mathbf{\tau }}_d}\)is the unknown applied disturbance,\({\mathbf{\tau }}\)is the control input.\({{\mathbf{\tau }}_f}={{\mathbf{F}}_C} \cdot {\text{sgn}}({\mathbf{\dot {q}}})+{{\mathbf{F}}_V} \cdot {\mathbf{\dot {q}}}\)is dedicated friction torque term, where\({{\mathbf{F}}_C}\)and\({{\mathbf{F}}_V}\)represent the Coulomb and viscous friction coefficients, respectively.

\({\mathbf{M}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right),{\mathbf{C}}\left( {{\mathbf{q,\dot {q}}}} \right),{\mathbf{G}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)are often unknown in practical engineering. Three RBF neural networks can be used to approximate\({\mathbf{M}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right),{\mathbf{C}}\left( {{\mathbf{q,\dot {q}}}} \right),{\mathbf{G}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)respectively. Denote the outputs of the RBF neural network as\({{\mathbf{M}}_{{\text{SNN}}}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right),{{\mathbf{C}}_{{\text{DNN}}}}\left( {{\mathbf{q,\dot {q}}}} \right),{{\mathbf{G}}_{{\text{SNN}}}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\), i.e.

To ensure the learned model preserves the fundamental structural properties of the manipulator dynamics, the RBF networks are structured as follows:

The network approximating\({\mathbf{M}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)is constrained to output a symmetric, positive definite matrix.

The network for\({\mathbf{M}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)is constructed such that the matrix\({\mathbf{\dot {M}-2C}}\)satisfies the skew-symmetry property.

The network for\({\mathbf{G}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)is designed to represent the gradient of a potential field.

These constraints are critical for maintaining the passivity of the system and ensuring the validity of the subsequent Lyapunov stability analysis.

Here,\({{\mathbf{E}}_M}\)\({{\mathbf{E}}_C}\)\({{\mathbf{E}}_G}\)is the approximation error of\({\mathbf{M}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right),{\mathbf{C}}\left( {{\mathbf{q,\dot {q}}}} \right),{\mathbf{G}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)respectively.

Substituting (2), (3) and (4) into (1), we obtain the following.

Where\({{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{M}}}\),\({{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{C}}}\),\({{\mathbf{W}}_G}\)are ideal weight of RBF and\({{\mathbf{\Psi }}_M}\)\({{\mathbf{\Psi }}_C}\)\({{\mathbf{\Psi }}_G}\)are output of hidden layer. \({\mathbf{E}}={{\mathbf{E}}_{\text{M}}}{{\mathbf{\ddot {q}}}_{\text{r}}}{\mathbf{+}}{{\mathbf{E}}_{\text{C}}}{{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}_{\text{r}}}{\mathbf{+}}{{\mathbf{E}}_{\text{G}}}\)。.

The estimation of\({{\mathbf{M}}_{{\text{SNN}}}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right),{{\mathbf{C}}_{{\text{DNN}}}}\left( {{\mathbf{q,\dot {q}}}} \right),{{\mathbf{G}}_{{\text{SNN}}}}\left( {\mathbf{q}} \right)\)is expressed by RBF neural network as follows.

Here,\({{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_M}\),\({{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_C}\),\({{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_G}\)is the respective estimate of\({{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{M}}}\),\({{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{C}}}\),\({{\mathbf{W}}_G}\).\({\mathbf{z=}}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\mathbf{q}}^{\text{T}}}}&{{{{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}}^{\text{T}}}} \end{array}} \right]{\kern 1pt}\),

Principle of control design

Define:

Where\({{\mathbf{q}}_{\text{d}}}\left( {\mathbf{t}} \right)\)is the ideal angle and\({\mathbf{q}}\left( {\mathbf{t}} \right)\)is the actual angle.

Define the sliding surface:

Then have:\({{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}_{\text{r}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}_{\text{d}}}{\mathbf{+\Lambda e}},{{\mathbf{\ddot {q}}}_{\text{r}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{\ddot {q}}}_{\text{d}}}{\mathbf{+\Lambda \dot {e}}},{\mathbf{\Lambda }}>{\mathbf{0}}\)

Submitting Eqs. (10) and (11) into Eq. (1), we have

The control law is composed of four components: a feedforward term based on the neural network approximation\({{\mathbf{\tau }}_{\text{m}}}\), a proportional feedback term\({{\mathbf{K}}_{\text{p}}}{\mathbf{r}}\), an integral term\({{\mathbf{K}}_{\text{i}}}\int {{\mathbf{rdt}}}\)to eliminate steady-state error, and a robust term\({{\mathbf{\tau }}_{\text{r}}}\)to counteract approximation errors and disturbances.

For the n-joint robot control system, the controller is proposed as follows:

Where\({{\mathbf{K}}_{\text{p}}}>{\mathbf{0}}, {{\mathbf{K}}_{\text{i}}}>{\mathbf{0}}\).

The nominal model control law is designed as

The robust term is designed as

Where\({{\mathbf{K}}_r}={\text{diag}}\left[ {{k_{rii}}} \right];{k_{rii}} \geqslant \left| {{E_i}} \right|\).

From (13) to (16), it can be obtained:

In which\({{\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}_{\text{M}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{M}}}{\mathbf{-}}{{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{\text{M}}}{\mathbf{,}}{{\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}_{\text{C}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{C}}}{\mathbf{-}}{{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{\text{C}}}{\mathbf{,}}{{\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}_{\text{G}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{G}}}{\mathbf{-}}{{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{\text{G}}}\). Due to the inclusion of the discontinuous sign function in the control law, we employ the Filippov theory to define the generalized solution of the system. The closed-loop error dynamics is given by Eq. (18):

The adaptive law is designed as:

Where \(k=1,2, \cdots n\),.Among them, \({{\mathbf{\Gamma }}_{M{\text{k}}}}\),\({{\mathbf{\Gamma }}_{{\text{Ck}}}}\),\({{\mathbf{\Gamma }}_{{\text{Gk}}}}\)are small positive numbers, which are referred to as correction coefficients.

Stability analysis of Lyapunov

For the designed control law, an integral Lyapunov function is designed.

Where\({{\mathbf{\Gamma }}_{Mk}}\)\({{\mathbf{\Gamma }}_{{\text{Ck}}}}\)\({{\mathbf{\Gamma }}_{Gk}}\)are symmetric positive-definite constant matrices.

From the control law (14) and the manipulator dynamics (1), the closed-loop error dynamics can be derived as:

Taking the derivative of the Lyapunov function, we have

Considering the skew-symmetric characteristics of the dynamic equation of the manipulator, \({{\mathbf{r}}^{\text{T}}}\left( {{\mathbf{\dot {M}-2C}}} \right){\mathbf{r}}=0\), we have

In the presence of the discontinuous term\({{\mathbf{K}}_{\text{r}}}{\text{sgn(}}{\mathbf{r}}{\text{)}}\), the stability analysis is conducted within the framework of Filippov’s theory for differential inclusions. The time derivative of the Lyapunov function is evaluated in a set-valued sense. Submitting (18) into above, we have

Since

Similarly, we have.

Thus.

Since.

The adaptation law is brought into the above equation and combined with \({k_{rii}} \geqslant \left| {{E_i}} \right|\). we have.

Because\({{\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}_{\text{M}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{M}}}{\mathbf{-}}{{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{\text{M}}}{\mathbf{,}}{{\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}_{\text{C}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{C}}}{\mathbf{-}}{{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{\text{C}}}{\mathbf{,}}{{\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}_{\text{G}}}{\mathbf{=}}{{\mathbf{W}}_{\text{G}}}{\mathbf{-}}{{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{\text{G}}}\). Therefore, it can be derived that:

Thus:

Choosing a larger\({{\mathbf{K}}_r}\)value is an appropriate choice to ensure that the robust controller can overcome uncertainties, that is,\({{\mathbf{K}}_r} \geqslant \left| {\mathbf{E}} \right|\), thereby providing a sufficient condition for ensuring the stability of the entire closed-loop system.Therefore,\({{\mathbf{r}}^{\mathbf{T}}}{\mathbf{E-}}{{\mathbf{r}}^{\mathbf{T}}}{{\mathbf{K}}_{\mathbf{r}}}\operatorname{sgn} \left( {\mathbf{r}} \right) \leqslant 0\)

Assuming:

\({{\mathbf{J}}_0}\)is a constant, and the following formula can be obtained:

Therefore,\({\mathbf{\dot {V}}}\)is negative definite, provided that the norms of\({\mathbf{r}}\)and\({\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}\)are sufficiently large. According to the Lyapunov theory,\({\mathbf{r}}\)and\({\mathbf{\tilde {W}}}\)are uniformly ultimately bounded. Moreover, by adjusting \({{\mathbf{K}}_{\mathbf{p}}}\), the tracking error and the weight estimation error can be reduced.

Hence.

Where\({{\mathbf{\lambda }}_{\hbox{min} }}({{\mathbf{K}}_p})\)is the smallest characteristic root of\({{\mathbf{K}}_{\mathbf{p}}}\).

Since\({\mathbf{V}}\left( 0 \right)\)and\({{\mathbf{\lambda }}_{\hbox{min} }}({{\mathbf{K}}_p})\) are positive constants, it follows that\({\mathbf{r}} \in {\mathbf{L}}_{2}^{n}\). Consequently,\({\mathbf{e}} \in {\mathbf{L}}_{2}^{n} \cap {\mathbf{L}}_{\infty }^{n}\), \({\mathbf{e}}\)is continuous and \({\mathbf{e}} \to 0\)as\({\mathbf{t}} \to \infty\), and\({\mathbf{\dot {e}}} \in {\mathbf{L}}_{2}^{n}\).

Furthermore, since\({\mathbf{\dot {V}}} \leqslant - {{\mathbf{r}}^T}{K_{\text{p}}}{\mathbf{r}} \leqslant 0\), it follows that\(0 \leqslant {\mathbf{V}} \leqslant {\mathbf{V}}\left( 0 \right)\),\(\forall t \geqslant 0\), Hence\({\mathbf{V}}\left( {\mathbf{t}} \right) \in {\mathbf{L}}_{\infty }^{{}}\)implies that \({{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{Mk}}\),\({{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{Ck}}\),\({{\mathbf{\hat {W}}}_{G{\text{k}}}}\)are bounded.

From\({\mathbf{e}} \in L_{2}^{n} \cap L_{\infty }^{n}\),\({\mathbf{\dot {e}}} \in L_{2}^{n}\),\({{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}_d} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\)and\({{\mathbf{\ddot {q}}}_{\text{d}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\)we can conclude that\({{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}_{\text{r}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\)and\({{\mathbf{\ddot {q}}}_{\text{r}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\), by observing that\({\mathbf{r}} \in L_{2}^{n}\),\({{\mathbf{q}}_{\text{d}}},{{\mathbf{\tau }}_{\text{r}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\), we can conclude that\({\mathbf{\dot {r}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\)from (18) and\({\mathbf{\tau }} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\)from (14). Using the fact that \({\mathbf{r}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\)and\({\mathbf{\dot {r}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\), and from Barbalat’s lemma, since\({\mathbf{r}} \in L_{2}^{n}\), and\({\mathbf{\dot {r}}} \in L_{\infty }^{n}\), it follows that\({\mathbf{r}} \to 0\)as\(t \to \infty\). Hence from the sliding surface definition\({\mathbf{r=\dot {e}+\Lambda e}}\), we have \({\mathbf{\dot {e}}} \to 0,{\mathbf{e}} \to 0\)as\(t \to \infty\).

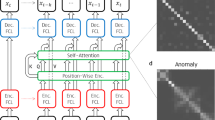

The algorithm flow chart is shown in the Fig. 2 below.

PSO-Optimized basis width parameters for RBF neural networks

The approximation capability of Radial Basis Function Neural Networks (RBFNNs) is influenced by the parameter settings of the hidden layer, particularly the width coefficient, which determines the input response characteristics-increasing its value can enhance generalization performance. Therefore, the autonomous optimization of the width coefficient becomes a key research focus. Existing training methods, such as the least squares method, gradient descent method, and intelligent algorithms, optimize the center points and widths of the intermediate layer as well as the weights of the output layer to minimize the mean squared error between the network output and the target function. This section focuses on optimizing the width coefficient. The Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm offers advantages including rapid convergence, strong global search capability, and resistance to becoming trapped in local optima, while also being insensitive to initial values. It is therefore employed.

Here’s the PSO optimization process for RBF basis width parameters: The PSO process for tuning basis width parameters\({b_M},{b_C},{b_G}\)in RBF neural networks begins with swarm initialization, where particles are randomly positioned in the parameter space with initial velocities. Each particle’s position represents a candidate solution for the basis widths. The algorithm then evaluates fitness by training the RBF network with each particle’s parameters and calculating the multi-objective fitness function J, which combines mean squared error and control input energy (Eq. (26). After fitness evaluation, the algorithm checks termination criteria (fitness improvement threshold or maximum iterations). If not terminated, it updates each particle’s personal best (pBest) when current fitness outperforms historical performance, then identifies the swarm’s global best (gBest). Particles then update their velocities using the PSO Eq. (27) and positions (28). This evaluation-update cycle repeats until termination, when the gBest position containing the optimized\({b_M},{b_C},{b_G}\)parameters is returned for RBF network implementation.

The process efficiently balances exploration and exploitation to minimize tracking error while regulating control energy, yielding robust basis width configurations that enhance RBF network performance.

The optimization process of RBF width coefficient based on particle swarm optimization algorithm is shown in Fig. 3. The optimal solution obtained after optimization using the PSO algorithm is\({b_M}=~13.9784\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_C}=12.2781\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_G}=13.9784\), and the fitness value is 0.1009.

The PSO algorithm parameters for optimizing RBF basis widths are set as follows: swarm size = 30; inertia weight\({\kern 1pt} w=0.6\); acceleration coefficients\({\kern 1pt} {c_1}={c_2}=1.5\); stopping criterion = 100; The optimization is terminated if the fitness improvement is less than 1e-6 for 10 consecutive iterations. A fixed random seed is used for reproducible results.

MATLAB Simscape modeling and simulation

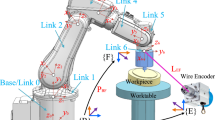

IRB1600 industrial robot

The modified MDH coordinate system and kinematic parameters of the robot are shown in Fig. 4; Table 1. The transformation relationship between two adjacent linkage coordinate systems,\(\left\{ {{O_{i - 1}}} \right\}\) and\(\left\{ {{O_i}} \right\}\), can be expressed by the homogeneous transformation matrix as follows:

That is

Therefore, the forward kinematics equation can be expressed as:

Simscape modeling

The robot model is imported into Solidworks and converted to URDF format using the SW2URDF plug-in, providing a detailed description of the robot’s structure, joints, links, and other parameters. Subsequently, the URDF file is processed by the Robotics System Toolbox in MATLAB to extract the robot model data. The fixed-step ODE4 (Runge-Kutta) solver is used with a step size of 0.001 s. This data is then used in Simscape Multibody to construct the physical model of the robot, incorporating joint actuation and setting physical attributes. The simulation environment is set up, and the simulation is executed to validate the accuracy and performance of the model. The dynamic model created is illustrated in the Fig. 5 below. Joint torque serves as the input, while the output consists of angular velocity and angular position of the joint. And the MATLAB Simscape control block diagram of the RBF control system is shown in Fig. 6. The control algorithm consists of several components including the desired trajectory, the control algorithm, the simulation model of the robot, and the actual trajectory.

Dynamic parameters

To ensure reproducibility, this section provides the complete dynamic parameters and simulation configuration. Dynamic Parameters of ABB IRB1600 Manipulator is shown in Table 2.

Controller integration and simulation

The initial states of the plant is\({q_d}_{1}={\kern 1pt} {q_{d2}}={q_{d3}}={q_{d4}}={q_{d5}}={q_{d6}}=0\),The desired trajectory is\({q_d}_{1}={q_{d2}}={q_{d3}}={q_{d4}}={q_{d5}}={q_{d6}}=0.1 \times cos\left( {2 \times pi \times t} \right)\).

For RBF neural network, the structure is 5–7-3,the input is\({\mathbf{z=}}\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\mathbf{q}}&{{\mathbf{\dot {q}}}}&{{\mathbf{\ddot {q}}}}&{\mathbf{e}}&{{\mathbf{\dot {e}}}} \end{array}} \right]\), the initial weight value is chosen as zero, We use control law(14)-(15)and adaptive law(18)-(20),.the parameters are chosen as \({{\mathbf{K}}_r}=30 \times 0.1 \times {\text{ones}}\left( {6,1} \right),{{\mathbf{K}}_p}=50 \times {\text{ones}}\left( {6,1} \right){\text{ }},{{\mathbf{K}}_i}=50 \times {\text{ones}}\left( {6,1} \right),{\mathbf{\Lambda }}=diag\left( {30,10,20,10,30,30} \right)\), the gain in the adaptive law is\({G_M}=100,{G_C}=100,{G_G}=100\)respectively. The center parameters of the RBF neural network are as follows:

To verify the optimal solution, parameters 2 and 3 are selected for comparison, as shown in Table 3 below.

To evaluate the compensation performance of the RBF neural network in robotic control, this study designed four sets of comparative simulation experiments, including a control group. The first group served as the baseline without any compensation strategy, while the other three groups incorporated the RBF neural network compensation mechanism, each configured with different width parameters for comparative validation.

The comprehensive experimental evaluation, as illustrated in Figs. 7, 8, 9 and 10, validates the efficacy of the parameter-optimized group. A comparative analysis of the tracking errors across all six degrees of freedom-encompassing joint angle, angular velocity, and angular acceleration-reveals a marked performance enhancement. Notably, the optimized controller achieves convergence to the desired trajectory within 0.5 s, concurrently exhibiting superior steady-state performance by maintaining the minimal error magnitudes and thus securing high-precision tracking.

Tables 4 and 5 present the joint angle RMSE and angular velocity RMSE corresponding to three parameter sets. The data analysis yields the following conclusions:

-

(1)

Parameter Sensitivity and Optimal Configuration: Control accuracy demonstrates significant sensitivity to the configuration of the RBF width parameters. Parameter Set 1 (\({b_M}=13.98\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_C}=12.28\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_G}=13.98\)) is identified as the optimal configuration, achieving superior tracking performance with a mean joint angle RMSE of 0.0107 rad and a mean angular velocity RMSE of 0.2824 rad/s. This suggests that the relatively higher values of\({b_M}\)and\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_G}\)are conducive to a more accurate approximation of the system’s nonlinear dynamics, thereby enhancing overall control performance.

-

(2)

Performance Degradation from Parameter Imbalance: A suboptimal parameter distribution, as exemplified by Set 2 (\({b_M}=3.03\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_C}=13.42\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_G}=10.39\)), leads to a marked degradation in performance. This set resulted in the highest tracking errors (0.0132 rad in angle and 0.4115 rad/s in angular velocity). The primary cause is attributed to an insufficient approximation capability for the inertia matrix due to the excessively low\({b_M}\)value, which weakens the modeling of inertial terms. Concurrently, an overly high\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_C}\)may introduce amplified estimation errors in the Coriolis and centrifugal force components.

-

(3)

Symmetric parameter configuration provides a balanced trade-off. Parameter Set 3 (\({b_M}=10\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_C}=10\),\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_G}=10\)) achieves angle RMSE (0.0111 rad) and angular velocity RMSE (0.2989 rad/s) close to those of Set 1, though Joint 4’s error (0.0124 rad) is slightly higher than in Set 1 (0.0118 rad). This symmetric setup simplifies parameter tuning while maintaining robust performance, making it suitable for scenarios prioritizing stability.

In summary, it is recommended to prioritize\({b_M}\)and\({\kern 1pt} {b_G}\)values within 12–14 while keeping\({\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {b_C}\)between 10–12.5.5 to avoid overfitting. For low-computational-resource scenarios, Set 3 is a viable choice, but attention should be paid to error fluctuations in Joints 4 and 6. Future work could explore adaptive parameter adjustment strategies to further optimize performance

Under identical RBF parameters, the joint errors were compared with traditional SMC-PID. The desired trajectory input for all six joints was set to \(0.1 \times \sin \left( {0.2 \times \pi \times t} \right)\), with the initial states all being zero. A comparison of the angular errors for the six joints is shown in Fig. 11. Observing the changes in the tracking errors of the six joints over time in the figure, RBFNN demonstrates superior performance in error magnitude, stability, and response speed. Although SMC-PID can rapidly reduce errors in certain joints during the initial phase, RBFNN exhibits smaller steady-state errors and lower error fluctuations throughout the entire 10-second test period, indicating its better long-term stability and precision. Furthermore, RBFNN’s response speed enables it to rapidly reach and maintain a smaller error range, whereas SMC-PID exhibits significant overshoot and oscillation. Therefore, RBFNN demonstrates better performance than SMC-PID in terms of initial phase stability, steady-state error, long-term stability, response speed, and error characteristics in all aspects.

Comparison of errors between RBF impedance and SMC-PID control. (a) Angle tracking error comparison errors of Joint 1, (a) Angle tracking error comparison errors of Joint 2, (c) Angle tracking error comparison errors of Joint 3, (d) Angle tracking error comparison errors of Joint 4, (e) Angle tracking error comparison errors of Joint 5, (f) Angle tracking error comparison errors of Joint 6.

Simulation and result analysis

The deterministic model’s input and output variables are established in ADAMS through the co-simulation with MATLAB. These variables facilitate data interaction with MATLAB. Control parameters, such as joint torques, are input from MATLAB Simulink to the robot model in ADAMS. The simulation function is executed within ADAMS. The joint data simulated by ADAMS is output to MATLAB via the mechanical control unit plug-in. Subsequently, the simulated joint data is compared with the expected values and fed into the RBF neural network for further analysis. The overall co-simulation control structure is illustrated in Fig. 12.

The simulation results depicted in Figs. 13, 14 and 15 are presented below. Figure 14 illustrates the schematic diagram of both the ideal trajectory and the tracking trajectory within the end workspace; Fig. 15 displays the tracking performance in the x, y, z direction dimensions and comprehensive displacement of the workspace; while Fig. 16 exhibits the tracking angles within the joint space, aligning with the tracking trajectory in MATLAB. The simulation outcomes suggest that the proposed control strategy achieves real-time workspace tracking under the tested conditions, indicating system stability and supporting its potential efficacy. However, further physical validation is required to confirm these findings.

Angle tracking of joint 1 (b) Angle tracking of joint 2.

The results show that the control algorithm can realize the real-time tracking of the manipulator, improve the robustness and adaptability of the system.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the construction and effectiveness of a complete, stability-guaranteed adaptive control framework. The results confirm that the systematic integration of adaptive RBF and SMC provides a potent solution for handling the nonlinearities and uncertainties inherent in industrial manipulators.

-

(1)

Designing and synthesizing an adaptive controller that effectively combines local model approximation via RBF networks, Lyapunov-based adaptive laws, and sliding mode control. The key engineering challenge of ensuring closed-loop stability within this combination is formally addressed. In simulations, this approach shows improved robustness and adaptability by handling specific uncertainties and nonlinear dynamics, reducing reliance on precise mathematical models.

-

(2)

By introducing the PSO algorithm to optimize the base width parameters of the RBF network, the network’s approximation ability and control performance were enhanced, and the real-time tracking control of the mechanical arm of the ABB IRB1600 industrial robot was achieved.

-

(3)

Through simulation, the optimized adaptive RBF neural network controller achieves real-time tracking control for the ABB IRB1600 manipulator. Results show that the proposed control strategy can reduce tracking errors compared to traditional algorithms.

-

(4)

The co-simulation using Simscape and ADAMS provides preliminary validation of the tracking performance and robustness under simulated conditions, indicating the potential credibility of the control algorithm. Its reliability in practical settings remains to be tested.

While simulation experiments have been conducted, the exclusive reliance on simulated environments (MATLAB/Simscape and ADAMS) without physical hardware validation remains a critical limitation. This gap impedes the assessment of the control strategy’s robustness against real-world disturbances such as sensor noise, mechanical wear, or environmental uncertainties.

Future work will explore the extension of the proposed control strategy to multi-arm collaborative scenarios and its integration with deep learning or reinforcement learning techniques to further enhance intelligent decision-making capabilities for complex industrial tasks.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article or supplementary information files. Furthermore, primary and secondary sources and data supporting the findings of this study were all publicly available at the time of submission.

References

Khanesar, M. A. & Branson, D. Robust sliding mode fuzzy control of industrial robots using an extended Kalman filter inverse kinematic solver. Energies 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/en15051876 (2022).

Truong, T. N., Vo, A. T. & Kang, H. J. Neural network-based sliding mode controllers applied to robot manipulators: A review. Neurocomputing 562, 126896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126896 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. Trajectory tracking control of wearable upper limb rehabilitation robot based on Laguerre model predictive control. Robot. Auton. Syst. 179 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2024.104745 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. A novel constraint tracking control with sliding mode control for industrial robots. Int. J. Adv. Rob. Syst. 18, 5682–5692. https://doi.org/10.1177/17298814211029778 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Sliding mode observer-based model predictive tracking control for Mecanum-wheeled mobile robot. ISA Trans. 151, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2024.05.050 (2024).

Zhang, T. et al. Discrete nonsingular terminal sliding mode control for trajectory tracking of space manipulators with mismatched multiple disturbances and noisy measurements. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 144 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2023.108766 (2024).

Cruz-Ortiz, D., Chairez, I. & Poznyak, A. Adaptive sliding-mode trajectory tracking control for state constraint master-slave manipulator systems. ISA Trans. 127, 273–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.08.023 (2022).

Zahra, A. K. A. & Abdalla, T. Y. A PSO optimized RBFNN and STSMC scheme for path tracking of robot manipulator. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inf. 12, 2733–2744. https://doi.org/10.11591/eei.v12i5.5018 (2023).

Arents, J. & Greitans, M. Smart industrial robot control Trends, challenges and opportunities within manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/app12020937 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Robot learning towards smart robotic manufacturing: A review. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 77 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcim.2022.102360 (2022).

Khan, G. D. Adaptive neural network control framework for industrial robot manipulators. IEEE Access. 12 https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3396782 (2024).

Yang, Z., Peng, J. & Liu, Y. Adaptive neural network force tracking impedance control for uncertain robotic manipulator based on nonlinear velocity observer. Neurocomputing 331, 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2018.11.068 (2019).

Hu, J. et al. Neural network-based adaptive second-order sliding mode control for uncertain manipulator systems with input saturation. ISA Trans. 136, 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2022.11.024 (2023).

Zhang, F., Yuan, Z. & Zhang, F. Research on coupling dynamics modeling and composite control of the multi-flexible space robot. Adv. Space Research: Official J. Comm. Space Research(COSPAR). 74 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2024.05.043 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Adaptive bias RBF neural network control for a robotic manipulator. Neurocomputing 447, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2021.03.033 (2021).

Yan, X. et al. Adaptive and intelligent control of a dual-arm space robot for target manipulation during the post-capture phase. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 142 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2023.108688 (2023).

Zhu, N., Xie, W. F. & Shen, H. Position-based visual servoing of a 6-RSS parallel robot using adaptive sliding mode control. ISA Trans. 144, 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2023.10.029 (2024).

Feng, H. et al. A new adaptive sliding mode controller based on the RBF neural network for an electro-hydraulic servo system. ISA Trans. 129, 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2021.12.044 (2022).

Jiang, P. et al. Energy consumption prediction and optimization of industrial robots based on LSTM. J. Manuf. Syst. 70, 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2023.07.009 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Error compensation of collaborative robot dynamics based on deep recurrent neural network. Chin. J. Eng. 43, 995–1002. https://doi.org/10.13374/j.issn2095-9389.2020.04.30.003 (2021).

Liu, S., Wang, L. & Wang, V. Sensorless haptic control for human-robot collaborative assembly. CIRP J. Manufact. Sci. Technol. 32, 132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2020.11.015 (2021).

Yu, X. et al. Human-Robot Co-Carrying using visual and force sensing. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 68, 8657–8666. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2020.3044792 (2020).

Hernandez-Sanchez, A. et al. Trajectory tracking controller of a robotized arm with joint constraints, a direct adaptive gain with state limitations approach. ISA Trans. 141, 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isatra.2023.07.004 (2023).

Sai, H. et al. Adaptive local approximation neural network control based on extraordinariness particle swarm optimization for robotic manipulators. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 36, 1469–1483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-022-0234-3 (2022).

Funding

This research was Funded by the National Science Foundation of China, grant number 52205536; funded by the Young Talent project of Scientific Research Plan of Education Department of Hubei Province, grant number Q20232301; funded by Wuhan Donghu High-tech Zone “Unveiling the List and Leading the Way” Project, grant number 2024KJB325.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, G.H., Y.P. and X.C.; methodology, G.H.; investigation, G.H.; formal analysis, G.H.; writing-preparation of the original draft, G.H.; writing-review and editing, Y.P., X.C., C.H., W.X. and Z.M.; visualization, C.H.; validation, W.X.; resources, Z.M.; funding acquisition, Y.P. and X.C.; project administration, Y.P. and X.C. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, G., Huang, C., Xiao, W. et al. Tracking control of industrial manipulator based on adaptive RBF neural network with local model approximation. Sci Rep 16, 4928 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34816-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34816-4