Abstract

Commercially available cannulation phantoms are expensive and primarily intended for adults. We designed and produced a neonatal cannulation phantom using three-dimensional printing. Different operators of varying clinical expertise successfully cannulated the phantom and inserted central catheter under ultrasound guidance. This is a reusable, realistic and valuable resource which can be used for training clinicians to gain practice, thereby improving hand-eye coordination, dexterity, confidence and safety during vascular access cannulation in newborn infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ultrasound (US) is a highly valuable and portable tool with wide applications in intensive care. Gaining vascular access using US improved first attempt insertions, overall procedural success and reduced complications1,2. US guided vascular access is increasingly used and recommended in the neonatal intensive care setting3,4,5. Umbilical venous catheters are increasingly inserted under US guidance6. Traditional methods of obtaining vascular access with percutaneously inserted central catheter (PICC) using anatomical landmarks has limitations. These limitations can vary depending on body habitus, skin tone and gestational age. There is growing evidence on best practice for US use in central line cannulation including guidance on safety and recommended techniques to reduce potential complications7,8,9. One of the recommendations is to use simulators for training9,10. Practicing with the phantom helps in estimating the depth of insertion, visualising the vessel and needle using US. Consequently, indirect benefits to the operator include improved dexterity, hand eye coordination, confidence and procedural safety11.

Commercially available vascular access simulators target the older children and adult patient and there is a distinct lack of cannulation phantoms and simulators replicating the vascular anatomy of newborn infants. The difference in the vessel dimensions, vessel depth and surrounding tissue in newborn infants is different from adults and this unique newborn architecture cannot be replicated in adult cannulation phantoms. Commercial neonatal phantoms may not perfectly replicate the complex anatomical properties such as vessel diameter in neonates with limited customization and durability. In addition, the high cost of commercially available cannulation phantoms limits the wider acceptance of this resource for training especially in resource limited settings. These shortcomings of commercial phantoms can be overcome to an extent with phantoms that have been customized specifically for neonatal use.

Three-dimensional printing is a commonly used resource that has applications in different industries including healthcare12,13,14. It is routinely applied in education and training15,16,17. We produced a reusable neonatal cannulation phantom for ultrasound-guided vascular access training using three-dimensional printed materials for neonatal clinicians to build PICC insertion skills. Our aim was to evaluate clinician experience and the performance of a prototype phantom to multiple US guided cannulation attempts by clinicians of varying expertise.

Materials and methods

The phantom was designed and produced in the Clinical Physics Department ofl Barts Health NHS Trust, London.

Cannulation Phantom production

All 3D printed components were developed using SolidWorks 3D CAD drawing software (Standard, SP0.0, 2022: Waltham, MA, USA) and printed on an Objet 260 Connex 3D printer (Stratasys, Eden Prairie, MN, USA).

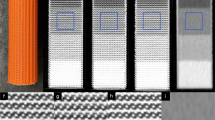

The phantom model encasement was 3D printed using VeroWhitePlus, which is a rigid general-purpose material. The dimensions of the phantom (175 × 132 mm, 72 mm height) were compatible with typical transducers used in neonatal intensive care. Vessel supports protruded from either side of the chambers, with a central channel to hold the 3D printed neonatal vein. These supports maintained the vessels at the correct position, relative to the phantom surface. The internal base of the phantom, consisted of an angled and soft surface made from Agilus30Black (soft rubber like material), to minimise reflections of the ultrasound energy back to the transducer. The phantom held 6 vessels (3 × 1.3 mm lumen and 3 × 1.4 mm lumen bore), with a wall thickness of 0.4 mm. The vessels were positioned 12 mm below the phantom surface. Each vessel was 3D printed using FLXA9895-DM, which is digital material mixture of VeroWhitePlus and Agilus30Black, with a Shore-A: 95 hardness value on the Durometer Shore hardness scale. The vessels were encased in an agar and glycerol-based tissue mimicking material (TMM)18 and covered with seam seal tape of 0.1 mm thickness (T3040: Ardmel Automation, Fife, UK), to protect the phantom surface and minimise desiccation (Fig. 1).

Testing the cannulation Phantom

The flow phantom was set up in the neonatal unit where the ultrasound scanner was housed. Uncoloured water was run through the model. The flow was kept constant by maintaining the height of the reservoir containing water. This produced continuous flow through the circuit (Fig. 2).

Ultrasound image acquisition and insertion technique

After placing water-based ultrasound jelly on the cannulation phantom, the operator placed a linear array probe (8-18 MHz GE, Vivid S70N, Bedfordshire, UK) held in the non-dominant hand to obtain optimal short axis (cross-sectional, out of plane view) and long axis (longitudinal, in plane) views of the vessel. Using the dominant hand, a 22G needle with a length of 40 mm was inserted at an angle of about 30–45 degrees, at a point 5–10 mm proximal to the middle marker of the probe on to the surface of the phantom, while keeping an optimal cross-sectional view. The needle was inserted until it reached the anterior wall of the vessel. The needle was then cautiously advanced at a shallower angle with ultrasound imaging of the indentation and penetration of the anterior wall of the vessel. The puncture of the vessel was also felt by the operator mimicking what one may expect in clinical practice. Extreme care was taken to ensure that the tip of the needle was maintained in the middle of the vessel lumen giving the appearance of a bullseye while gradually advancing the needle and the probe in short < 1 mm increments. This was to ensure that the needle did not breach the posterior vessel wall and the entire length of the needle tip was inserted. Once the needle was confirmed to be in the centre of the vessel lumen using US, a metal guidewire was inserted through the needle for insertion of a PICC using a Seldinger technique (Figs. 3 and 4). A metal guidewire was used as it could easily go through the caliber of the needle that was used and could readily be visualized using US. Non-ultrasound confirmation of the correct placement was also achieved by continued advancement of the guide wire which resulted in the guide wire being physically visible at the exit end of the vessel outside the phantom.

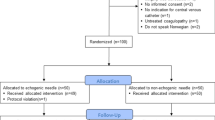

Operators carrying out the cannulation

Clinicians of varying expertise carried out the cannulation using US imaging. Prior experience in US and US guided PICC placement was noted.

Operator questionnaire

All operators were given a questionnaire (supplemental file 1) prior to cannulation which captured their experience before and after using the phantom.

Results

Two rounds of testing were performed. The first round was performed by clinicians (SP and AKS) to test the proof of concept design. The overall performance of the phantom was deemed satisfactory. During the initial measurement series, approximately 25 cannulation attempts were performed. The guidewire was seen to clearly pass through the vessel lumen (Figs. 3 and 4) with US. Non-ultrasound confirmation included continued advancement of the guide wire which resulted in it coming out through the exit end of the vessel. Perforation of the plastic covering of the phantom resulted in exposure of the tissue-mimicking material to environmental conditions, which could lead to desiccation and subsequent alteration of the phantom’s physical properties. To mitigate these effects and preserve the integrity of the phantom, the plastic covering was replaced (Fig. 5), thereby enhancing its durability and extending its functional lifespan.

During the second round of testing, approximately 50 phantom surface / skin perforations were recorded on vessel one, and 20 on vessel two. Minimal leakage of phantom fluid was observed upon reapplication of the skin after the initial cannulation series. Despite multiple use and some leakage around the cannulation sites, the image quality was minimally affected and was comparable to our prior work using the same 3D printed materials19.

A questionnaire (supplemental file 1) was administered to clinicians prior to cannulation. Ten neonatal clinicians of varying expertise (junior clinical fellow, six neonatal registrars, three neonatal consultants and an interventional radiology consultant) carried out cannulation of the phantom in a single session after receiving a short period of training on acquiring images and inserting the line. The minimum neonatal experience for the clinicians ranged from just under a year to more than 2 years for the majority of clinicians. All the neonatal clinicians have had experience with inserting PICC in patients without using ultrasound in clinical practice.

Half of operators had received some form of US guided PICC placement training, from other providers, prior to the session, although only one third had used US on patients. Following our training, all operators were successful in identifying the vessel, reporting the US image appeared true to life; 60% were able to successfully cannulate and insert the guidewire through the needle by the end of the first session. The median score (on a scale of 1–5) for usefulness of the session on improving cannulation skills was 4.5 among the clinicians.

We performed a post session feedback questionnaire to evaluate user feedback. 90% agreed that there would be an improvement in accuracy of line placement, a reduction in the complications (failure, multiple attempts, bleeding, damage to local structures), and consequently improved safety for the patient. 80% reported an increase in their ability to use US guided PICC placement; all operators were keen to receive further training to enhance their skills and increase confidence.

Discussion

We designed and produced a reusable neonatal cannulation phantom which can be used for newborn and infant vascular access training for clinicians involved with newborn intensive care including but not limited to medical and nursing students, paediatricians, neonatologists, vascular access nurses and interventional radiologists. We used three-dimensional printing, a technique enabling personalised and cost-effective innovation, to produce this cannulation phantom.

The US imaging produced by the cannulation phantom mimicked what one would expect to see in-vivo. The entire length of the needle was visible and there was a good tactile feel when the needle penetrated the vessel providing the operator with another degree of confirmation in addition to ultrasound imaging. The results from this work demonstrate that clinicians reported easy vessel identification using ultrasound which resembled in-vivo appearance of vessel using ultrasound. They also reported improved confidence similar to other studies20. Randomised trials comparing indigenously developed ultrasound phantoms with commercially available models for ultrasound guided vascular access training have shown to be a comparable alternative in resource-limited setting21. Shrimal et al. compared commercial phantoms with low cost gelatinous phantoms for ultrasound guided needle tracking in their randomised crossover trial and found that this was non-inferior to commercial phantoms in terms of tissue resemblance and overall performance22. Additionally, Sajadi and colleagues compared commercial phantoms with homemade models. They found that the overall score for the homemade models with gelatin was significantly higher and comparable with human anatomy23.

Another advantage of this phantom is that it is reusable, realistic and devoid of infection/ hygiene related concerns which can be an issue where biological materials have been used. During our practice session, two approaches were used. One was visualisation of the long axis (longitudinal, in plane) view first followed by the short axis (cross sectional, out of plane) view to confirm needle tip position and vice-versa. There was no difference in successful cannulation as has been shown in randomised trials comparing these two methods24. We used a needle to insert the guide wire in this study and ensured that the bevel is within the vessel lumen before careful insertion of the guidewire. If operators chose to use a cannula to insert the PICC, it is important that the cannula is inserted all the way to the hub to ensure that the plastic component is well within the lumen and not penetrating the posterior wall. This will provide stability for the cannula to remain in place once the needle is removed.

This is the first iteration of the cannulation phantom and is not without limitations. Studied vessel lumen diameters were either 1.3–1.4 mm with the intention of replicating the basilic, cephalic and long saphenous veins in newborn infants. The vessels were at a depth of 12 mm which can mimic real life scenarios especially with large babies who are more likely to have difficulties with obtaining vascular access due to body habitus. This work represented the initial proof-of-concept phantom and a limited operational lifespan for the phantom was anticipated. We did not explore any other factors such as technical challenges among clinicians with varied experience as our goal was to evaluate clinician performance and phantom performance only. To minimise experimental variability, the vessel depth was fixed at 12 mm. Our next iteration will consider vessels at a range of depths to enhance anatomical realism. We used water to flow through the circuit, which was visible on colour Doppler. We did not colour the water and therefore, this made visualisation of the fluid in the cannula hub/ needle difficult once the vessel was punctured. It is likely that higher viscosity fluid would flow through the vessel. No significant leakage from the multiple perforations to the vessel was encountered, obviating the need for a more viscous material which would remain within the vessel despite several cannulation attempts. This cannulation phantom was designed to mimic venous flow and therefore we only tested it using continuous flow and not pulsatile flow. As the vessels were at a depth of 12 mm, we were unable to use the commonly used 24-gauge cannula (19 mm length, BD Neoflon™) through which a PICC is passed by some practitioners. We therefore had to use a longer 40 mm 22G needle. The protective cover was replaced after the first set of measurements to minimise desiccation. However, we did not have to repeat this and the phantom continued to provide good images despite multiple cannulation attempts. The phantom wall bowed with age prompting us to use thicker walls during our next iteration. We only used qualitative measures to quantify phantom wear from multiple cannulations. Lastly, all the neonatal clinicians were experienced in inserting PICC in patients without the use of ultrasound in clinical practice which made it difficult to compare their experience using ultrasound on the phantom with cannulation in patients.

There are several benefits of using three-dimensional printing. Vessels can be tailored and manufactured to our needs giving flexibility of producing veins of differing sizes that can be inserted at variable depths that would not necessarily been seen with commercially available vessels. The three-dimensional printed vessels that we produced were soft and realistic mimicking real life cases. The vessels have been validated for continuous and pulsatile flow use with ultrasound25,26. The model that we created worked well with water alone and thus obviating the need for expensive Doppler fluid. The cost of the materials used for producing this bespoke cannulation phantom was approximately £300 which is a lot less than commercially available phantoms that target older children and adults. Lastly, the flow phantom was constructed with 6 vessels to increase usage and longevity.

Having established that the vessels within the phantom can withstand multiple cannulation attempts without significant deterioration, the next phase of development will focus on enhancing the phantom’s clinical relevance by:

-

Positioning the vessels at varying depths within the phantom to better simulate a range of anatomical and clinical scenarios.

-

Investigating the incorporation of ballistic gels to improve the phantom’s biomechanical properties, thereby achieving elasticity and acoustic characteristics that more closely approximate those of human soft tissues.

-

Use of objective markers to measure durability of the phantom following multiple use.

Conclusion

We successfully designed and produced a cannulation phantom for use in newborn infants. Cannulation was successfully performed using US by clinicians with varying levels of experience thus demonstrating versatility, realism and generalizability. This will assist clinicians in gaining practical skills for US guided insertion of PICC in newborn infants.

Data availability

Study data can be made available upon request from Jonathan Reeves, Jas Bansal and Ajay K. Sinha.

References

Cajozzo, M. et al. Comparison of central venous catheterization with and without ultrasound guide. Transfus. Apher Sci. 31, 199–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transci.2004.05.006 (2004).

Agarwal, A., Singh, D. K. & Singh, A. P. Ultrasonography: a novel approach to central venous cannulation. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 13, 213–216. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-5229.60174 (2009).

Thakur, A., Kumar, V., Modi, M., Kler, N. & Garg, P. Use of point of care ultrasound for confirming central line tip position in neonates. Indian Pediatr. 57, 805–807 (2020).

Sharma, D., Farahbakhsh, N. & Tabatabaii, S. A. Role of ultrasound for central catheter tip localization in neonates: a review of the current evidence. J. maternal-fetal Neonatal Medicine: Official J. Eur. Association Perinat. Med. Federation Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 32, 2429–2437. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2018.1437135 (2019).

Singh, Y. et al. International evidence-based guidelines on point of care ultrasound (POCUS) for critically ill neonates and children issued by the POCUS working group of the European society of paediatric and neonatal intensive care (ESPNIC). Crit. Care. 24, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2787-9 (2020).

Polonio, P. L., Tumin, D., Zheng, Y., Gandhi, A. & Bear, K. Implementation of point of care ultrasound to assess umbilical venous catheter position in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. maternal-fetal Neonatal Medicine: Official J. Eur. Association Perinat. Med. Federation Asia Ocean. Perinat. Soc. Int. Soc. Perinat. Obstet. 35, 7207–7209. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2021.1946508 (2022).

NICE. Guidance on the use of ultrasound locating devices for placing central venous catheters, (2002). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta49/resources/guidance-on-the-use-of-ultrasound-locating-devices-for-placing-central-venous-catheters-pdf-2294585518021

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central et al. Practice guidelines for central venous access: a report by the American society of anesthesiologists task force on central venous access. Anesthesiology 116, 539–573. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c9569 (2012).

Franco-Sadud, R. et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for central and peripheral vascular access in adults: A position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J. Hosp. Med. 14, E1–E22. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3287 (2019).

Murphy, P. C. & Arnold, P. Ultrasound-assisted vascular access in children. Continuing Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain. 11, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkq056 (2011).

Jaffer, U., Normahani, P., Singh, P., Aslam, M. & Standfield, N. J. Randomized study of teaching ultrasound-guided vascular cannulation using a Phantom and the freehand versus needle guide-assisted puncture techniques. J. Clin. Ultrasound: JCU. 43, 469–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.22263 (2015).

Liaw, C. Y. & Guvendiren, M. Current and emerging applications of 3D printing in medicine. Biofabrication 9, 024102. https://doi.org/10.1088/1758-5090/aa7279 (2017).

Li, H., Fan, W. & Zhu, X. Three-dimensional printing: the potential technology widely used in medical fields. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 108, 2217–2229. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.a.36979 (2020).

Maglara, E. et al. Three-Dimensional (3D) printing in orthopedics education. J. Long. Term Eff. Med. Implants. 30, 255–258. https://doi.org/10.1615/JLongTermEffMedImplants.2020036911 (2020).

de Souza, M. A., Bento, R. F., Lopes, P. T., de Pinto Rangel, D. M. & Formighieri, L. Three-dimensional printing in otolaryngology education: a systematic review. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 279, 1709–1719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-07088-7 (2022).

Jones, D. G. Three-dimensional printing in anatomy education: assessing potential ethical dimensions. Anat. Sci. Educ. 12, 435–443. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1851 (2019).

Blohm, J. E. et al. Three-Dimensional printing in neurosurgery residency training: A systematic review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 161, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2021.10.069 (2022).

Teirlinck, C. J. et al. Development of an example flow test object and comparison of five of these test objects, constructed in various laboratories. Ultrasonics 36, 653–660 (1998).

Pereira, S. et al. Three-Dimensional printed flow Phantom model of the carotid artery in preterm Infants- vessel lumen diameter measurements using different printing materials. Br. J. Healthc. Med. Res. 12 https://doi.org/10.14738/bjhmr.121.18129 (2025).

Sabak, M., Al-Hadidi, A., Demashkieh, L., Zengin, S. & Hakmeh, W. Homemade phantoms improve ultrasound-guided vein cannulation confidence and procedural performance on patients. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 28, 1312–1316. https://doi.org/10.14744/tjtes.2022.74712 (2022).

Abraham, S. V. et al. Indigenously developed ultrasound Phantom model versus a commercially available training model: randomized Double-blinded study to assess its utility to teach ultrasound guided vascular access in a controlled setting. J. Med. Ultrasound. 30, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.4103/JMU.JMU_48_21 (2022).

Shrimal, P. et al. Comparing commercial versus low-cost gelatinous phantoms for ultrasound-guided needle tracking: A randomized crossover trial, among emergency medicine residents. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 24, 103–110. https://doi.org/10.4103/tjem.tjem_206_23 (2024).

Sajadi, K. et al. Comparison of commercial versus homemade models for teaching Ultrasound-Guided peripheral I.V. Placement. J. Emerg. Med. 62, 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2022.01.003 (2022).

Erickson, C. S. et al. Ultrasound-guided small vessel cannulation: long-axis approach is equivalent to short-axis in novice sonographers experienced with landmark-based cannulation. West. J. Emerg. Med. 15, 824–830. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2014.9.22404 (2014).

Pereira, S. et al. Three-dimensional printed flow Phantom model of the carotid artery in preterm infants for training and research. J. Biomedical Eng. Med. Imaging. 8, 102–114 (2021).

Pereira, S. S. et al. Inter- and intra-scanner differences in doppler flow measurements using three-dimensional printed flow Phantom model of the carotid artery in preterm infants. J. Biomedical Eng. Med. Imaging. 9 https://doi.org/10.14738/jbemi.91.11679 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all staff at the Clinical Physics Department for their support in this work. We are also thankful to all the neonatal staff for participation in training and feedback on the cannulation phantom.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JS collected feedback from participants. JS & AKS analysed the data. AKS, JR, JS, FS, MB and SK wrote the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pereira, S.S., Reeves, J., Bansal, J. et al. Three-dimensional printed neonatal cannulation phantom for ultrasound-guided vascular access training. Sci Rep 16, 4641 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34863-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34863-x