Abstract

Middle ear cholesteatoma (cholesteatoma), also known as a cholesteatomatous chronic otitis media, is concerning because it expands into the middle ear with bone destruction and causes irreversible hearing loss. Surgical resection is currently the only curative treatment, but the high recurrence rate remains a major problem, necessitating the development of novel therapies. In our previous study, we demonstrated that histone modifications are involved in the pathogenesis of cholesteatoma and that keratinocyte growth factor (KGF)-induced murine cholesteatoma is suppressed by administration of MI-503, a menin-MLL inhibitor. This study was designed to assess the therapeutic potential of menin-MLL inhibitors for the non-surgical management of cholesteatoma and to elucidate their mechanism of action. For the in vitro study, a growth inhibition assay was performed by administering menin-MLL inhibitors to mouse-derived primary tympanic membrane epithelial cells. For the in vivo study, menin-MLL inhibitors were topically administered into a KGF-induced murine cholesteatoma for seven consecutive days. The therapeutic effects on cholesteatoma were analyzed using micro-computed tomography imaging. The menin-MLL inhibitors reduced KGF-induced cholesteatoma in vivo (3/3, 100%). Among the menin-MLL inhibitors, BMF-219 (50 µM), a covalent menin inhibitor, showed the strongest inhibitory effect against cholesteatoma, with a 70.75 ± 8.92% rate of residual lesion. These findings show promising results for the therapeutic use of menin-MLL inhibitors in the non-surgical management of cholesteatoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Middle ear cholesteatoma (cholesteatoma) is classified as a form of chronic otitis media, but its tissue consists of p63-positive tympanic membrane epithelial cells (TMECs) and displays a unique pathogenesis distinct from that of benign or malignant tumors1,2. Cholesteatoma accounts for approximately 25% of all cases of hearing loss, with an estimated prevalence of 500,000 individuals in the United States and an incidence of 3 per 100,000 in children and 9.2 per 100,000 in adults3. On the other hand, a recent report from the UK, based on an examination of the overall prevalence of cholesteatoma in the UK Biobank, indicates a cholesteatoma incidence rate of 0.22%, equivalent to approximately 1 in 500 individuals4. It is a progressive and intractable disease that damages both the middle and inner ear, resulting in hearing loss and dizziness, thus requiring timely therapeutic intervention5.

Currently, surgical removal is the only available treatment. However, postoperative complications such as hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, facial nerve palsy, and intracranial involvement, along with a high recurrence rate (up to 37% for children, 15% for adults at 5-year follow-up6), remain significant challenges. These limitations highlight the urgent need for a novel and effective therapeutic approach.

We previously demonstrated that induction of trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and the promotion of proliferation of p63-positive epithelial stem/progenitor cells in a keratinocyte growth factor (KGF)-induced mouse cholesteatoma in vivo2,7,8. As an epigenetic regulator, menin associates with mixed lineage leukemia 1 (MLL), which catalyzes H3K4me3 at promoter regions of target genes9,10,11. This complex is crucial for transcriptional regulation in stem/progenitor cells12. Based on this mechanism, we hypothesized that inhibiting menin-MLL interaction could suppress disease-specific gene expression by reducing H3K4 methylation. In fact, our previous studies have demonstrated that MI-503, a menin-MLL inhibitor, significantly suppresses the proliferation of p63-positive epithelial cells and reduces cholesteatoma tissue in vivo8.

Moreover, menin has been shown to interact with the myelocytomatosis (MYC) family of transcription factors, which bind to enhancer elements13,14. MYC overexpression has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of cholesteatoma15. Thus, we hypothesized that inhibitors targeting the menin-MLL interaction with dual effects, blocking both the trimethylation of H3K4 and the interaction with the MYC family, may represent an effective therapeutic strategy. Menin-MLL inhibitors such as MI-216, MI-46317, VTP5046918, and BMF-21919 were primarily developed to block the interaction between menin and MLL1, inhibiting the transcription of oncogenic target genes in MLL-rearranged leukemia. Specifically, MI-2 belongs to the first-generation class of small-molecule inhibitors that target the menin-MLL interaction, acting as a thienopyrimidine compound that blocks the protein–protein interaction of menin and MLL16. MI-463 and VTP50469 are MI-2 analogs; they are more potent inhibitors of the menin-MLL interaction and possess favorable properties in terms of oral bioavailability17,18. VTP50469 works by displacing menin from chromatin and inhibiting the occupancy of MLL at specific gene loci, which leads to changes in gene expression, differentiation, and apoptosis18. BMF-219 is distinguished as a highly selective and irreversible menin inhibitor19. It is also designed to target MYC activity, which is significantly dependent on its interaction with menin19.

The main objective of this study was to qualify the most effective menin-MLL inhibitor for suppressing cholesteatoma growth in vitro and in vivo. The secondary objective was to elucidate the mechanism of action by which menin-MLL inhibitors reduce cholesteatoma tissue. To explore these, we used the following experimental models: an in vitro model utilizing mouse-derived primary TMECs20, and an in vivo model of KGF-induced cholesteatoma in mice21.

Results

Menin-MLL inhibitors reduced cell growth

To determine the effects of covalent menin-MLL inhibitor (BMF-219) or reversible menin-MLL inhibitors (VTP50469, MI-463, and MI-2) against the growth rate of TMECs, cell growth inhibition experiments were done in the presence of menin-MLL inhibitors at the concentrations of 1.0 μM and 0.5 μM. The results of cell growth inhibition experiments using TMECs showed that some of the menin-MLL inhibitors, BMF-219 and VTP50469, demonstrated a growth-inhibitory effect at concentrations of 0.5 μM or 1.0 μM as early as Day 1 after administration (Fig. 1a). MI-463 and MI-2 demonstrated a growth-inhibitory effect at concentrations of 1.0 μM at Day 3 after administration (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, the covalent menin inhibitor, BMF-219, exhibited higher efficacy compared to other menin-MLL inhibitors. The growth-inhibitory effect of BMF-219 was shown to be both dose-dependent and time-dependent (Fig. 1a, Table 1).

The menin-MLL inhibitors inhibit the growth rate and the expression level of cyclin D1 (CCND1) of mouse-derived primary tympanic membrane epithelial cells (TMECs) in vitro. (a) Growth rate of the TMECs in CnT-PR media for 1, 3, and 5 days in the absence (PBS, circle, line) or presence of 0.5 µM (triangle, dashed line) or 1.0 µM (square, dotted line) menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2). The cells were used at passage 3. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 3). ***, p < 0.001, **, p < 0.01, *, p < 0.05, ns, non-significant (one-way analysis of variance test, followed by Dunnett’s tests for normally distributed data). d0, Day 0, d1, Day 1, d3, Day 3, d5, Day 5. (b) Western blot analysis using antibodies against cyclin D1 (CCND1). The expression level of CCND1 in the TMECs was reduced after administration of the 0.5 µM or 1.0 µM menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2). β-actin was used as a loading control. The full blots are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 3). ****, p < 0.0001 (one-way analysis of variance test, followed by Dunnett’s tests for normally distributed data).

Menin-MLL inhibitors reduced c-MYC signaling

According to the results of Western blot analysis, after treatment with covalent (BMF-219) or reversible menin-MLL inhibitors (VTP50469, MI-463, and MI-2) at concentrations of 1.0 μM and 0.5 μM, expression of cyclin D1 (CCND1), a downstream target of c-MYC, was reduced (Fig. 1b). β-actin, used as a control, showed almost the same protein levels across all samples (Fig. 1b). After adjusting CCND1 expression levels based on β-actin expression levels in all samples, a significant difference was observed between the menin-MLL inhibitor group (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, and MI-2) and the control group (PBS) (p < 0.0001, Fig. 1b).

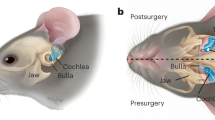

Menin-MLL inhibitors reduced mouse cholesteatoma in vivo

To evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of menin-MLL Inhibitors in suppressing mouse cholesteatoma in vivo, we examined the ears by otoendoscopy and micro–computed tomography (micro-CT), as described previously22 (Fig. 2a). As in previous reports8, otoendoscopic examination revealed the cholesteatoma formations in all ears transfected with the KGF-expression vector (Fig. 2b, Pre, dotted circle). At Day 7 after treatment with BMF-219 (5 µM or 50 µM) in the ears, a significant reduction of the cholesteatoma was observed in all ears (Fig. 2b, Post Day 7, arrows). After administration of 5 µM or 50 µM VTP50469 against the mouse cholesteatoma, the volume of cholesteatoma was reduced (Fig. 2b, Post Day 7, arrows). The results of micro-CT analysis indicated that the volume of soft-tissue density (STD) decreased in all mouse cholesteatoma after the treatment with BMF-219, VTP50469, and MI-463 compared to the PBS group (Fig. 2b). Quantitative analysis of the STD area showed a significant reduction in cholesteatoma volume in mice treated with BMF-219 (50 µM, p < 0.01; 5 µM, p < 0.05, Fig. 2c, Table 2). These results indicated that the covalent menin inhibitor BMF-219 demonstrated a suppressive effect on murine cholesteatoma with a lower concentration (5.0 μM) and shorter duration (7 consecutive days of administration) (Fig. 2b, c, Table 2).

Effects of menin-MLL inhibitors against cholesteatoma in vivo. (a) Schematic description of the method for administration of menin-MLL inhibitors in vivo. The menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2, 5 μM or 50 μM each) were administered by topical administration on seven consecutive days against KGF-induced cholesteatoma. Before and after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors, otoendoscopic examination (Otoendoscopic Exam) and micro-computed tomography (CT) scanning were performed. (b) Otoendoscopic view of the tympanic membrane in the KGF-expression vector-transfected ears before (Pre) and after (Post Day 7) administration of menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2). Before menin-MLL inhibitors are administered, cholesteatoma (dashed circle) forms in the ears of a mouse (Pre). After administration of menin-MLL inhibitors in the ear, the reduction of cholesteatoma (arrows) was indicated (Post Day 7). Horizontal sections of micro-CT images of the temporal bones of the mouse in the KGF-expression vector-transfected ears before (Pre) and after (Post Day 7) administration of menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2). The soft tissue density area is shown in gray, and the aeration area is shown in black. Red square, left ear; Blue square, right ear. (c) Results of the calculation of the volume of soft tissue density area of the red or blue squares. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 3). **, p < 0.01, *, p < 0.05, ns, not significant (one-way analysis of variance test, followed by Dunnett’s tests for normally distributed data). Pre, before administration of menin-MLL inhibitors, Post, Day 7 after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors.

Immunohistochemical analysis in vivo

The results of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed that BMF-219 (50 µM) administered ears were just like a normal tympanic membrane (Fig. 3a, Fig. S2). To analyze the effects of menin-MLL inhibitors on the methylation of H3K4 in mouse cholesteatoma cells, we performed immunohistochemical analysis using an anti-H3K4me3 antibody (Fig. 3a, Fig. S2). As a result, the number of H3K4me3-positive cells in the epithelium and subepithelium significantly decreased in the BMF-219 (50 µM, 5 µM), VTP50469 (50 µM, 5 µM), and MI-463 (50 µM, 5 µM) administered ears than in PBS-administered ears (Fig. 3b, Table 3). To analyze the effects of menin-MLL inhibitors on the proliferative activity of epithelial cells in mouse cholesteatoma, we performed immunohistochemical analysis using an anti-Ki67 antibody (Fig. 3a, Fig. S2). The Ki67-positive cells were shown in the epithelium and subepithelium. As a result, in the menin-MLL inhibitors-administered ears (BMF-219 [50 µM, 5 µM], VTP50469 [50 µM, 5 µM], and MI-463 [50 µM]), a significant reduction in the number of Ki67-positive cells was observed compared with PBS-administered ears (Fig. 3c, Table 3). To analyze the effects of menin-MLL inhibitors against the c-MYC signaling in mouse cholesteatoma cells, we performed immunohistochemical analysis by using an anti-CCND1 antibody, a downstream target of c-MYC (Fig. 3a, Fig. S2). The CCND1-positive cells were shown in the epithelium and subepithelium. As a result, in the menin-MLL inhibitors-administered ears (BMF-219 [50 µM, 5 µM], VTP50469 [50 µM], and MI-463 [50 µM]), the CCND1-positive cell number was significantly lower than in PBS-administered ears (Fig. 3d, Table 3).

The histological analysis of temporal bones after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors in vivo. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, 5 µM or 50 μM) or PBS. Immunohistochemical detection of H3K4me3, Ki67, and cyclin D1(CCND1) in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors or PBS. Immunostaining shows a higher magnification of the boxed area in the H&E staining column. The positive cells were stained in brawn (arrows). Nuclei were counterstained with Hematoxylin (blue). Scale bars, 100 µm. (b) Linear columns indicate the labeling index of positive cells of H3K4me3 in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2, 5 μM or 50 μM each). Closed columns indicate the labeling index of H3K4me3 in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of PBS. (c) Linear columns indicate the labeling index of positive cells of Ki67 in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2, 5 μM or 50 μM each). Closed columns indicate the labeling index of Ki67 in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of PBS. (d) Linear columns indicate the labeling index of positive cells of CCND1 in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, MI-2, 5 μM or 50 μM each). Closed columns indicate the labeling index of CCND1 in the sections of mouse cholesteatoma after administration of PBS. Data shown are mean ± SD (n = 3). Quantitative analysis of the labeling index of positive cells between the cholesteatoma with the administration of menin-MLL inhibitors and PBS administration. ****, p < 0.0001, ***, p < 0.001, **, p < 0.01, *, p < 0.05, ns, not significant (one-way analysis of variance test, followed by Dunnett’s tests for normally distributed data).

Discussion

These results suggest that menin-MLL inhibitors are promising candidate drugs for the treatment of cholesteatoma. In both in vitro and in vivo models, cell proliferation, c-MYC signaling, and cholesteatoma formation were reduced in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Notably, the covalent inhibitor BMF-219 demonstrated greater inhibitory effects than other reversible menin-MLL binding inhibitors.

Menin-MLL inhibitors act on both menin and the histone methyltransferase MLL. Methylation of histone H3K4 at the promoter region of target genes, promoted by the menin and MLL complex, is associated with gene activation and disease onset8,9,10,23. In other words, suppression of H3K4 methylation reduces the expression of target genes24.

Specifically, the covalent menin inhibitor BMF-219 has a higher binding affinity than other menin-MLL inhibitors and acts by forming an irreversible bond with the cysteine residue (Cys329) on menin, thereby preventing menin from interacting with MLL and inhibiting the expression of cell cycle-related proteins such as KMT2A and JunD25,26,27. In addition, this mechanism is linked to the suppression of the MYC signaling pathway, which further contributes to the inhibition of tumor cell growth and disease progression19,28. Suppression of c-MYC signaling has been recognized as a key strategy for controlling hyperproliferative diseases29. The results of the Western blot analysis demonstrated that all menin-MLL inhibitors effectively suppress the expression of CCND1, a downstream factor of c-MYC, suggesting potential therapeutic efficacy against hyperproliferative diseases such as cholesteatoma. Immunohistochemical analysis also showed a significant decrease in the expression of proliferation markers in the treatment groups, supporting a mechanism of action involving cell cycle regulation. These findings would support the potential development of menin-MLL inhibitors as a new therapeutic approach for cholesteatoma and related diseases30. However, the causal relationship between H3K4me3 downregulation, reduced c-MYC levels, and cholesteatoma suppression remains incompletely elucidated, necessitating further investigation into the mechanism by which menin-MLL inhibitors suppress cholesteatoma.

The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and the short duration of the evaluation period for the inhibitory drug effect. And more, to generalize the results of this study, a multi-center study is necessary. Comparing results from different facilities will improve the reliability of the results. Further research is needed to overcome these limitations. In particular, studies with larger sample sizes, long-term follow-up, and multi-center studies are important. While this study demonstrated promising results in animal models, extrapolating findings from animal experiments to humans presents significant limitations due to inherent challenges. The translation of these findings into clinical success requires rigorous validation in human-relevant systems. Regarding safety, although previous reports have confirmed the absence of middle ear mucosal or inner ear damage with a specific menin-MLL inhibitor22, comprehensive ototoxicity evaluations are still necessary for the various inhibitors used in the current study.

In conclusion, this study shows that menin-MLL inhibitors can reduce cholesteatoma induced in specimens by repeated KGF-expression vector transfection. Residual and recurrent cholesteatoma remains a problem, but menin-MLL inhibitor can be considered safe and may be effective in reducing recurrence. Modulation of histone modifications may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for the non-surgical management of cholesteatoma. Further multicenter, prospective studies with larger patient cohorts are warranted to confirm these preliminary findings.

Materials and methods

Animals

The ICR mice (6 weeks, male, n = 15, or 3 weeks, male, n = 3) with normal ears were obtained from CLER Japan Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the protocols approved by the Guidelines for Animal Experimentation of Jikei University with approval guidelines (No. 2022-084C1). The findings of this study were reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for experimental reporting31,32.

Cell culture

The mouse TMECs were prepared by primary explant culture, as described previously20. The cells were seeded at a density of 4 × 104 cells per well in 12-well plates, grown in CnT-PR basal media (Cellntec, Bern, Switzerland) in the presence or absence of 0.5 or 1.0 μM menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, or MI-2) (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX) in 2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)(SigmaAldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS (n = 3), and culture media was replaced every 24 to 48 h (h). All primary cell cultures were performed in a humidified chamber at 37 °C with 5% CO2. To determine the cell numbers, the growing cells in the plates were incubated in 0.25% trypsin in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 10 min, neutralized with fetal bovine serum (Lot 08020002, 35-0790CV, Corning, Corning, NY) and washed in PBS, followed by cell counting in a hemocytometer (DHC-N01, NanoEntek, Seoul, Korea) using the T1-SM Nikon Microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) at Day1, 3, and 5 (n = 3, each).

Western blot analysis

Cells (4.0 × 105) were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed directly in 2 × Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) supplemented with 2-mercaptoethanol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp., Osaka, Japan) and a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA)33. The lysates were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min to achieve complete protein denaturation, followed by brief centrifugation to remove debris. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% gradient polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the iBlot dry transfer apparatus (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% skim milk prepared in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T). After rinsing the blocking three times in TBS-T, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After additional washes, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) and captured with the LAS-4000 imaging platform (GE Healthcare). Densitometric analysis was conducted using ImageJ software (version 1.51, NIH, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/), and signal intensity was normalized to β-actin. Antibody information is summarized in Table 4.

Administration of menin-MLL inhibitors in the mouse cholesteatoma model

A KGF-expression vector was transfected into the epithelial region of the external auditory canal of mice every four days, for a total of five times, following the previously established protocol (Fig. 2a)21. After confirming cholesteatoma formation in vivo by otoendoscopic observation using a 0° rigid endoscope (AVS Co., Tokyo, Japan), menin-MLL inhibitors (BMF-219, VTP50469, MI-463, and MI-2; 5.0 µM or 50 µM dissolved in DMSO/PBS; n = 3 per group) were applied topically to the ear canal once daily for seven consecutive days. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was administered in the same manner to the control group. Otoendoscopic evaluations were performed one day after the final inhibitor application, as previously described8.

Micro-computed tomography analysis

The volume of the cholesteatoma lesion in each mouse was quantified using a micro-CT imaging system for small animals (LaTheta LCT-200; Hitachi Aloka Medical Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), as described previously22. Micro-CT scanning of the temporal bone was conducted under general anesthesia, induced with ketamine, xylazine, and acepromazine, on Day 4 following the final KGF-expression vector transfection and Day 1 after the last administration of the menin-MLL inhibitors. Reconstructed CT images were generated using the instrument’s built-in software, applying an empirically defined bone threshold (gray scale range, 400–2000). The images were subsequently processed in Adobe Photoshop to delineate STD regions within the middle ear cavity. Quantitative assessment of the STD area was performed on coronal CT slices intersecting the mid-cochlear level, using ImageJ software version 15.1 (NIH, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Histological analysis

Following the final treatment, animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal administration of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). The temporal bones were dissected, immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde prepared in PBS (pH 7.4) for approximately 17 h, and subsequently rinsed in PBS. Decalcification was performed using 10% EDTA (pH 7.4) at 4 °C for seven days. After decalcification, specimens were embedded in paraffin, and serial sections of five µm thickness were cut for histological examination. Sections were stained with H&E using standard histological procedures and evaluated microscopically34.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining based on enzyme labeling was carried out following previously described protocols34,35. Paraffin-embedded temporal bone sections (5 µm thick) were prepared as reported previously34,35. For antigen retrieval, the slides were autoclaved in HistoVT One solution (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) at 90 °C for 20 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the sections with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol. To minimize nonspecific antibody binding, sections were pretreated with 500 µg/ml normal goat IgG in 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Primary antibodies were then applied and incubated, followed by washing and incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Antigen-antibody complexes were visualized using a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The nuclei were counterstained with Hematoxylin. For negative controls, normal mouse IgG (1:100) or normal rabbit IgG (1:100) was used in place of the primary antibody. Antibody information is summarized in Table 4.

Image analysis

Images of H&E and enzyme-based immunohistochemical staining were acquired using an AxioCam digital camera coupled with AxioVision software version 4.8 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) under a light microscope. For quantification of H3K4me3-, Ki67-, and CCND1-positive cells, three to five randomly selected microscopic fields per sample were imaged, and the acquired images were processed using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Hematoxylin counterstaining was performed to determine the total number of nuclei, allowing calculation of the proportion of positively stained cells. The enzyme-immunohistochemistry results were graded as positive or negative compared with the negative control, and the number of cell nuclei was counted at more than 1000 nuclei in three equal epithelial regions at 400× magnification.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed as described above, and labeling indices were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical differences among groups were assessed using a one-way analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test for comparisons with the control group. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP software version 13 (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Kuo, C. L. Etiopathogenesis of acquired cholesteatoma: Prominent theories and recent advances in biomolecular research. Laryngoscope 125, 234–240 (2015).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T., Akiyama, N., Takahashi, M. & Kojima, H. Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) modulates epidermal progenitor cell kinetics through activation of p63 in middle ear cholesteatoma. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 19, 223–241 (2018).

Kemppainen, H. O. et al. Epidemiology and aetiology of middle ear cholesteatoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 119, 568–572 (1999).

Wilson, E. et al. Epidemiology of cholesteatoma in the UK Biobank. Clin. Otolaryngol. 50, 316–329 (2025).

Castle, J. T. Cholesteatoma pearls: Practical points and update. Head Neck Pathol. 12, 419–429 (2018).

Møller, P. R. et al. Recurrence of cholesteatoma: A retrospective study including 1,006 patients for more than 33 years. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 24, e18–e23 (2020).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T. & Akiyama, N. Keratinocyte growth factor signaling promotes stem/progenitor cell proliferation under p63 expression during middle ear cholesteatoma formation. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 28, 291–295 (2020).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T., Akiyama, N., Tatsumi, N., Okabe, M. & Kojima, H. Menin-MLL inhibitor blocks progression of middle ear cholesteatoma in vivo. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 140, 110545 (2021).

Schuettengruber, B., Chourrout, D., Vervoort, M., Leblanc, B. & Cavalli, G. Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell 128, 735–745 (2007).

Malik, R. et al. Targeting the MLL complex in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 21, 344–352 (2015).

Shimoda, H. et al. Inhibition of the H3K4 methyltransferase MLL1/WDR5 complex attenuates renal senescence in ischemia-reperfusion mice by reduction of p16INK4a. Kidney Int. 96, 1162–1175 (2019).

Cui, K. et al. Chromatin signatures in multipotent human hematopoietic stem cells indicate the fate of bivalent genes during differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 4, 80–93 (2009).

Dempke, W. C. M., Desole, M., Chiusolo, P., Sica, S. & Schmidt-Hieber, M. Targeting the undruggable: Menin inhibitors ante portas. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 9451–9459 (2023).

Wu, G. et al. Menin enhances c-Myc-mediated transcription to promote cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 9, 16195 (2018).

Ozturk, K. et al. Evaluation of c-MYC status in primary acquired cholesteatoma by using fluorescence in situ hybridization technique. Otol. Neurotol. 27, 588–591 (2006).

Jedwabny, W. et al. Theoretical models of inhibitory activity for inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: Targeting menin–mixed lineage leukemia with small molecules. MedChemComm 8, 2216–2227 (2017).

Borkin, D. et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the menin-MLL interaction blocks progression of MLL leukemia in vivo. Cancer Cell 27, 589–602 (2015).

Krivtsov, A. V. et al. A menin-MLL inhibitor induces specific chromatin changes and eradicates disease in models of MLL-rearranged leukemia. Cancer Cell 36, 660-673.e11 (2019).

Dempke, W. C. M. et al. Targeting the undruggable: Menin inhibitors ante portas. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 9451–9459 (2023).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T., Pinto, F., Pitt, K. & Senoo, M. Inhibition of TGF-β signaling enables long-term proliferation of mouse primary epithelial stem/progenitor cells of the tympanic membrane and the middle ear mucosa. Sci. Rep. 13, 4532 (2023).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T. et al. In vivo over-expression of KGF mimics human middle ear cholesteatoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 272, 2689–2696 (2014).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T., Akiyama, N., Hirabayashi, M., Shimmura, H. & Kojima, H. Epigenetic regulation as a new therapeutic target for middle ear cholesteatoma. Otol. Neurotol. 44, 273–280 (2023).

Matkar, S., Thiel, A. & Hua, X. Menin: A scaffold protein that controls gene expression and cell signaling. Trends Biochem. Sci. 38, 394–402 (2013).

Bi, L. et al. CPF impedes cell cycle re-entry of quiescent lung cancer cells through transcriptional suppression of FACT and c-MYC. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 24, 2229–2239 (2020).

Thomas, X. Small molecule menin inhibitors: Novel therapeutic agents targeting acute myeloid leukemia with KMT2A rearrangement or NPM1 mutation. Oncol. Ther. 12, 57–72 (2024).

Brown, M. R. & Soto-Feliciano, Y. M. Menin: From molecular insights to clinical impact. Epigenomics 17, 489–505 (2025).

Canichella, M., Papayannidis, C., Mazzone, C. & de Fabritiis, P. Therapeutic implications of menin inhibitors in the treatment of acute leukemia: A critical review. Diseases 13, 227 (2025).

Lourenco, C. et al. MYC protein interactors in gene transcription and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 579–591 (2021).

Shin, M. H. et al. A RUNX2-mediated epigenetic regulation of the survival of p53 defective cancer cells. PLoS Genet. 12, e1005884 (2016).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T. & Akiyama, N. Therapeutic agent for cholesteatoma. WO Patent 2025110175 (2025).

McGrath, J. C., Drummond, G. B., McLachlan, E. M., Kilkenny, C. & Wainwright, C. L. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: The ARRIVE guidelines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 1573–1576 (2010).

Kilkenny, C., Browne, W., Cuthill, I. C., Emerson, M. & Altman, D. G. Animal research: Reporting in vivo experiments—the ARRIVE guidelines. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 1577–1579 (2010).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T. et al. Keratinocyte growth factor stimulates growth of p75+ neural crest lineage cells during middle ear cholesteatoma formation in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 192, 1573–1591 (2022).

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T., Akiyama, N. & Kojima, H. L1CAM–ILK–YAP mechanotransduction drives proliferative activity of epithelial cells in middle ear cholesteatoma. Am. J. Pathol. 190, 1667–1679 (2020).

Akiyama, N., Yamamoto-Fukuda, T. & Kojima, H. Effect of histone acetyltransferase inhibitor against middle ear cholesteatoma in a mouse model. Auris Nasus Larynx 52, 657–663 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The KGF-expression vector was kindly provided by K. Matsumoto.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP25K12821 and JP22K09753 (to T. Y-F).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Y-F. conceived and designed the work, performed the experiments, collected and analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript; N.A. performed the experiments, collected and analyzed data, and proofread the manuscript; H.K. proofread the manuscript. All authors approved the last version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamoto-Fukuda, T., Akiyama, N. & Kojima, H. Menin-MLL inhibitors as a new therapeutic target for middle ear cholesteatoma. Sci Rep 16, 2539 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34922-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34922-3