Abstract

While renal replacement therapy (RRT) allows for precise fluid management as well as addressing electrolyte imbalances and the removal of other necessary compounds, its early initiation has not shown benefit in the general critically ill population. Moreover, the effects of early RRT initiation specifically in patients on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) also remain unclear. This retrospective study investigated adult patients who underwent VA-ECMO between April 2018 and March 2022 and used the clone-censor-weight method to emulate a hypothetical target trial and compare two groups: patients who initiated RRT within 2 days of VA-ECMO initiation (Early) and those who did not (Late). The primary outcomes were 28-day and 90-day hospital mortality analyzed by Cox proportional hazards models and the secondary outcome was 90-day RRT dependence by pooled logistic regression models. Inverse probability censoring weights were applied to adjust the models. A total of 2,513 VA-ECMO patients were cloned into both groups. The 28-day and 90-day mortalities were lower in the Early group (HR 0.59 [95% CI 0.53–0.68] and 0.67 [0.61–0.75]). However, the early group experienced greater RRT dependence at 90 days than the late group (OR 2.58 [1.94–3.46]). In conclusion, early initiation of RRT (within 2 days of VA-ECMO) was associated with lower hospital mortality but with a higher likelihood of 90-day RRT dependence in adult patients on VA-ECMO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a lifesaving intervention and venoarterial ECMO (VA-ECMO) is used for patients with severe cardiovascular failure. Patients requiring ECMO are critically ill, frequently presenting with multiple organ failure, and are at high risk of developing acute kidney injury (AKI), which occurs in up to 85% of ECMO patients1,2,3,4. AKI is a recognized risk factor for mortality in patients receiving ECMO4,5, and renal replacement therapy (RRT) is required in 40 to 50% of these patients5,6.

Patients with VA-ECMO may develop AKI due to severe cardiogenic shock as well as other factors, including hypotension, insufficient renal perfusion, renal congestion due to fluid overload or congestive heart failure, the presence of inflammatory mediators, ischemia-reperfusion injury, and/or hemolysis7,8,9,10. Patients on VA-ECMO also face risks of transfusion overload because of volume resuscitation and coagulation disorders, with renal congestion from excessive transfusion during shock potentially exacerbating the AKI11. In fact, fluid management is a common indication of RRT initiation in patients on ECMO. According to a previous worldwide survey, the management (43%) or prevention (16%) of fluid overload were the main reasons for initiating RRT during ECMO12. Furthermore, a retrospective cohort study has shown that fluid accumulation during ECMO is associated with worse prognosis, suggesting that RRT to remove excess fluid may improve clinical outcomes13.

Previous studies examining the optimal timing of RRT initiation in general ICU populations have suggested that early initiation may not improve mortality14,15,16. However, patients on ECMO were either underrepresented or not adequately reported in these studies, and clinical outcomes of early versus delayed initiation of RRT during ECMO have not been specifically explored. The Target Trial Emulation is a novel causal inference method in observational studies that addresses not only confounding bias but also immortal time and selection bias17. Dynamic clinical parameters can be incorporated into the modeling of treatment strategies to account for their influence18. Based on the above, the goal of our study was to determine whether early RRT initiation during VA-ECMO improves mortality and other clinical outcomes using the novel Target Trial Emulation method.

Methods

Study design and data source

This is a retrospective analysis of the Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) database as a comprehensive and nationwide health claims data source to conduct a hypothetical target trial. The DPC database is an administrative health claims database in Japan, involving more than 1,700 hospitals, most of which are acute care hospitals with 92% (244/266) coverage of tertiary medical institutions in Japan19. The database includes patient demographic data, diagnostic information based on ICD-10 codes, patient dispositions, treatments, surgeries, medications, and the use of medical devices and supplies. From this database, we extracted hospital admission information from April 2018 to March 2022 for our study patients, and acquired outpatient and inpatient information up to five years prior to each admission as pre-admission data. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Review Board of Institute of Science Tokyo (M2000-788), which also waived the requirement for informed consent from patients due to the anonymization of the data.

Study participants

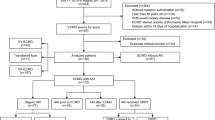

Our study targeted adult patients aged 18 and over who were admitted to the ICU and used VA-ECMO during the specified period. Since information on the specific type of ECMO support was not available in the DPC database during the study period, we identified VA-ECMO cases based on ICD codes, following a previous DPC study with modifications20, and included patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, pulmonary embolism, hypothermia, poisoning, or trauma (a list of ICD codes is available in Supplementary Table 2). Cases where ECMO charges were considered as temporary use of cardiopulmonary bypass during cardiac surgery were excluded. We also excluded patients who did not have ECMO initiated on the day of or the day after ICU admission, patients who used RRT before the initiation of ECMO, patients with a diagnosis of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) either during the current hospital stay or in outpatient/inpatient data from the past five years (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, we excluded patients diagnosed with viral pneumonia to preclude patients on venovenous ECMO (Supplementary Table 2). A design diagram visualizing the above is available in the Supplementary Materials (Supplementary Fig. 1)21.

Treatment strategies (intervention and comparison)

We defined the two treatment strategies compared in the hypothetical target trial based on the timing of initiating RRT. The patient cohort that initiated RRT on the day of or the day after starting VA-ECMO was classified as the Early group, and the cohort that did not was classified as the Late group. The implementation of RRT was defined as the presence of recorded charges both for the RRT procedure itself and for the use of dialysis fluid or replacement fluid.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes were hospital mortality at 28 days and 90 days from the initiation of VA-ECMO (Supplementary Fig. 2). The secondary outcome was RRT dependence at 90 days from the initiation of VA-ECMO. RRT dependence was defined as follows: (1) In patients hospitalized for more than 90 days, if RRT is undergone at 90 days; (2) For periods of 90 days or less, if RRT is undergone in the 3 days prior to discharge or death. Additionally, death was considered as a competing risk for RRT dependence (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Covariates

We included factors that could affect treatment selection and outcomes as model covariates, including: age, sex, smoking status (never smoker vs. current/past smoker), admission due to cardiovascular disease, presence of obesity (defined as a body mass index of ≥ 30 or not), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)22,23, presence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) based on ICD-10 codes, emergency admission status, ICU type (1 to 4, according to Japanese health system), each component of the SOFA score at the initiation of ECMO, concurrent use of intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), use of Impella, use of ventricular assist device (VAD), administration of antibiotics, implementation of targeted temperature management, use of vasopressors, use of inotropes, volume of intravenous fluid administration (adjusted for days and body weight, and categorized by tertile), execution of cardiac surgery, execution of aortic aneurysm surgery, execution of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), use of loop diuretics, and exposure to nephrotoxins. Detailed definitions for each covariate are described in the Supplementary Table 3. Of note, there were missing values for smoking status, height, weight, and each component of SOFA score, which were imputed using Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE)24. The missing rates for these variables are available in Supplementary Table 5.

Statistical analysis

We employed a novel causal inference concept known as the Target Trial Emulation using the clone-censor-weight method to address confounding, selection, and immortal time bias in observational studies17,25. Initially, cloning involved copying the entire cohort data to create two identical cohorts. One was designated as the arm to assign to the Early group, and the other to the Late group. Next, we processed artificial censoring for patients who deviated from the protocols of their respective treatment strategies (Supplementary Fig. 3). Specifically, in the Early group, if RRT was not initiated by the day following the start of ECMO, it was considered as a deviation from the emulated protocol. Similarly, patients in the Late group who started RRT on the day of or the day after starting ECMO were also considered deviations and thus censored. While cloning ensures both groups have the same baseline characteristics, the introduction of artificial censoring presents a potential source of bias as treatment strategies were not randomly assigned. To address this, we utilized inverse probability of censoring weighting (IPCW), which is essential for adjusting the bias introduced by artificial censoring. This adjustment makes the comparison between the groups fair, enhancing the validity of our analysis despite the non-random assignment of treatment strategies. IPCW was calculated as the probability of remaining uncensored at each event, employing a Cox regression model that included the aforementioned covariates. Utilizing this weighting to analyze mortality as the primary outcome, we applied the Cox proportional hazards model. We calculated the adjusted survival from this model and plotted the adjusted survival curve up to 90 days from the initiation of ECMO. For secondary outcomes of RRT dependence, we used pooled logistic regression, considering death as a competing risk event. Estimation of hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) was achieved through nonparametric bootstrapping, with the process repeated 1,000 times. Furthermore, we conducted analyses for primary and secondary outcomes in the crude cohort without cloning. Similar to the analysis in the Target Trial Emulation, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models for mortality and logistic regression for RRT dependence were used in the crude cohort analysis. Covariates in these multivariate models were the same ones used in the IPCW for the Target Trial Emulation.

As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted the same analysis on the primary outcomes for a cohort excluding patients with CKD, encompassing analyses in both the crude cohort and the Target Trial Emulation. This is because we incorporated CKD as a covariate in the models without considering the severity levels of the condition, which could lead to misclassification of ESKD or the underestimation of patients at high risk for RRT. Additionally, as a supplemental analysis, we conducted the same analysis on the secondary outcome (RRT dependence), limiting the cohort to survivors only.

Results

Characteristics of the crude cohort

Among 52,820 adult patients who underwent VA-ECMO, 2,513 were selected for analysis based on pre-defined eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Across the entire cohort, the median age was 69 years (interquartile range [IQR] 56–77), 35.4% were female, and 98.3% were admitted for cardiovascular disease (Table 1). The prevalence of CKD was 5.4%, and the median CCI was 2 (IQR 0–2). The median SOFA score and its renal component were 10 (IQR 8–12) and 0 (IQR 0–2), respectively. 516 patients (20.5%) started RRT within 2 days of ECMO initiation, while 1,997 (79.5%) did not. A total of 1,560 patients (62.0%) did not undergo RRT during hospitalization. The overall mortality rate of the cohort was 61.7%, and the median duration of VA-ECMO was 2 days (IQR 2–4) (Supplementary Table 6).

Hospital mortality

In both the unadjusted models and the models adjusted for covariates of the crude cohort, as well as in the models in the Target Trial Emulation, a reduction in risk for hospital mortality was observed with the Early vs. Late strategy (Fig. 2; Table 2). In the Target Trial Emulation, the HR for 28-day mortality was 0.59 (95% CI 0.53–0.68), and for 90-day mortality, the HR was 0.67 (95% CI 0.61–0.75). The results from the sensitivity analysis using the cohort excluding CKD patients were consistent in all models except for the model adjusted for covariates in the crude cohort for 90-day mortality (HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.76–1.01) (Supplementary Table 7). In the sensitivity analysis, the HR in the Target Trial Emulation models in the sensitivity analysis was 0.58 for 28-day mortality (95% CI 0.52–0.67) and 0.65 for 90-day mortality (95% CI 0.58–0.74).

Adjusted survival curve in patients on VA-ECMO stratified by RRT strategy. VA-ECMO venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. The Y-axis displays the adjusted survival based on the Cox proportional hazards model weighted by IPCW obtained in the Target Trial Emulation. The X-axis represents the number of days from ECMO initiation.

RRT dependence

For 90-day RRT dependence, both models using the crude cohort and those employing the Target Trial Emulation consistently showed increased odds in the Early group (Table 3). The OR for 90-day RRT dependence in the Early group in the Target Trial Emulation model was 2.58 (95% CI 1.04–3.46). In the analysis of survivors only, increased odds in the Early group were observed in all models (Supplementary Table 8). In the Target Trial Emulation model for survivors only, the OR was 3.77 (95% CI 1.66–9.86).

Discussion

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the Japanese nationwide health claims data to investigate the effects of early RRT initiation on mortality risk and RRT dependence among patients on VA-ECMO. We employed a novel causal inference method known as the Target Trial Emulation, which effectively addresses not only confounding and selection biases but also the immortal time bias17,18. Using this method, we found that early initiation of RRT in adult VA-ECMO patients reduced the risk of hospital mortality at both 28 and 90 days, with consistent risk reduction observed in both conventional analyses and those with the Target Trial Emulation. However, for 90-day RRT dependence, the risk was consistently higher with early initiation of RRT.

Numerous studies have explored the timing of RRT initiation in overall critical care populations, with multiple Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) failing to show a mortality benefit from early RRT initiation strategies14,15,16. However, these studies mostly excluded patients with high disease severity or did not specify ECMO usage. As a result, the effects on the most severe cohort of patients who are most likely to benefit from meticulous fluid management were removed or diluted in the analyses. In line with this, our study demonstrated a potential mortality benefit from the early RRT initiation strategy in ECMO patients, highlighting that trials involving heterogeneous ICU populations may not represent all ICU patients.

To date, few studies have explored the optimal timing for RRT initiation in ECMO patients, and none are as large-scale as this study. A retrospective cohort study in Korea involving 296 patients, including 210 cases of VA-ECMO and 86 cases of Venovenous ECMO, reported no significant difference in 30-day mortality between ECMO patients who started RRT within 72 h of ECMO initiation and those who did not26. Similarly, a single-center pilot RCT in China, which compared an early initiation of RRT within 12 h of starting ECMO (n = 21) with standard care (n = 20), found no significant difference in 30-day mortality. In these studies, immortal bias in the late group complicates the interpretation, and the Target Trial Emulation used in our study effectively demonstrated the mortality benefit of early RRT initiation that was not proven in the previous study27.

Although this study lacks detailed information on how fluid management through RRT was conducted, the observed reduction in mortality risk with early RRT initiation may suggest that early RRT may break the vicious cycle consisting of circulatory failure, venous congestion including renal congestion, renal impairment, and fluid overload in VA-ECMO patients28. Previous studies have reported that VA-ECMO patients have a higher risk of developing AKI compared to non-ECMO patients, and it is generally known that AKI increases mortality, and brings more challenges in fluid management1,29,30. The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization guideline recommends initiating RRT for ECMO patients if fluid overload by AKI is unresponsive to diuretics, or AKI impedes the recovery from circulatory/respiratory failure31. Our study indicates that proactive use of RRT from the early days of VA-ECMO management improves patient outcomes.

It is intriguing to find that RRT dependence at 90 days was greater in the Early group in this study. This result is consistent with the STARRT AKI trial, but not with a past meta-analysis published before the STARRT AKI trial14,32. One possible reason is the hemodynamic changes associated with RRT. Intermittent hemodialysis and continuous RRT have been suggested to reduce renal perfusion33, induce myocardial stunning34, and alter hemodynamics35, which may subsequently contribute to decreased urine output and impaired kidney function36,37. It is also uncertain whether these changes occur in the severely critical condition of VA-ECMO. In addition to hemodynamic changes, inflammation due to exposure to RRT may also contribute. Intensive RRT use has been associated with inflammatory markers and apoptosis markers, such as TNFR1, and this inflammatory environment has been associated with poor renal prognosis38,39,40,41. This potential impact may have been more pronounced in the Early group, which had longer exposure to RRT.

However, we must acknowledge the limitations to our work. As a retrospective analysis of data recorded in the database, we could not account for unknown or unmeasured confounders, including the detailed indications for VA-ECMO. Additionally, owing to the nature of Japanese health claims data, the method of selecting the target population of VA-ECMO patients based on ICD codes, while used in previous studies20, may have caused misclassification and selection bias. Moreover, detailed clinical information, such as laboratory data and fluid balance, was unavailable, making it challenging to consider specific parameters related to the indication for RRT as well as the assessment of AKI stages. Furthermore, the lack of detailed data on CKD stage and pre-admission baseline kidney function means that the results cannot be generalized to CKD patients. Finally, the absence of information on not initiating or discontinuing RRT due to futility before death may have introduced potential indication bias and affected the results. However, the strength of our study lies in enhanced validity of our findings due to utilization of nationwide large-scale data and minimization biases through the application of the Target Trial Emulation approach, including cloning and adjustment using IPCW with 28 covariates, as well as conducting sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions

Initiating RRT within 2 days of starting VA-ECMO was associated with improved hospital mortality but also with an increased risk of 90-day RRT dependence. Further investigation is needed to explore causal inferences using a wider variety of data sources and to conduct evaluations of long-term outcomes, impacts on patient quality of life, and cost-effectiveness.

Data availability

Data will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DPC:

-

Diagnosis procedure combination

- ECMO:

-

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- ESKD:

-

End stage kidney disease

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IABP:

-

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IPCW:

-

Inverse probability censoring weighting

- MICE:

-

Multivariate imputation by chained equations

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- RRT:

-

Renal replacement therapy

- SOFA:

-

Sequential organ failure assessment

- VA-ECMO:

-

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- VAD:

-

Ventricular assist device

References

Yan, X. et al. Acute kidney injury in adult postcardiotomy patients with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: evaluation of the RIFLE classification and the acute kidney injury network criteria. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 37, 334–338 (2010).

Han, S. S. et al. Effects of renal replacement therapy in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a meta-analysis. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 100, 1485–1495 (2015).

Chen, H., Yu, R. G., Yin, N. N. & Zhou, J. X. Combination of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and continuous renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients: a systematic review. Crit. Care 18, 675 (2014).

Lin, C. Y. et al. RIFLE classification is predictive of short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with acute renal failure supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Nephrol. Dial Transplant. 21, 2867–2873 (2006).

Thongprayoon, C. et al. Incidence and impact of acute kidney injury in patients receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 8, 981 (2019).

Rajsic, S. et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock: a meta-analysis of mortality and complications. Ann. Intens. Care 12, 93 (2022).

Ostermann, M. & Lumlertgul, N. Acute kidney injury in ECMO patients. Crit. Care 25, 313 (2021).

Chen, Y. C., Tsai, F. C., Fang, J. T. & Yang, C. W. Acute kidney injury in adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 113, 778–785 (2014).

Schrier, R. W. & Abraham, W. T. Hormones and hemodynamics in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 577–585 (1999).

Metra, M. et al. Worsening renal function in patients hospitalised for acute heart failure: clinical implications and prognostic significance. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 10, 188–195 (2008).

Chen, L. et al. Intraoperative venous congestion rather than hypotension is associated with acute adverse kidney events after cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 128, 785–795 (2022).

Fleming, G. M. et al. A multicenter international survey of renal supportive therapy during ECMO: the kidney intervention during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (KIDMO) group. ASAIO J. 58, 407–414 (2012).

Kim, H. et al. Permissive fluid volume in adult patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation treatment. Crit. Care 22, 270 (2018).

STARRT-AKI Investigators. Timing of initiation of renal-replacement therapy in acute kidney injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 240–251 (2020).

Gaudry, S. et al. Initiation strategies for renal-replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 122–133 (2016).

Barbar, S. D. et al. Timing of renal-replacement therapy in patients with acute kidney injury and sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1431–1442 (2018).

Hernán, M. A. & Robins, J. M. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am. J. Epidemiol. 183, 758–764 (2016).

Fu, E. L. et al. Timing of dialysis initiation to reduce mortality and cardiovascular events in advanced chronic kidney disease: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 375, e066306 (2021).

Aso, S., Matsui, H., Fushimi, K. & Yasunaga, H. In-hospital mortality and successful weaning from venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: analysis of 5,263 patients using a national inpatient database in Japan. Crit. Care. 20, 80 (2016).

Aso, S., Matsui, H., Fushimi, K. & Yasunaga, H. The effect of intraaortic balloon pumping under venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on mortality of cardiogenic patients: an analysis using a nationwide inpatient database. Crit. Care Med. 44, 1974–1979 (2016).

Schneeweiss, S. et al. Graphical depiction of longitudinal study designs in health care databases. Ann. Intern. Med. 170, 398–406 (2019).

Quan, H. et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am. J. Epidemiol. 173, 676–682 (2011).

Quan, H. et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med. Care 43, 1130–1139 (2005).

van Buuren, S., Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. & Mice Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–67 (2011).

Maringe, C. et al. Reflection on modern methods: trial emulation in the presence of immortal-time bias. Assessing the benefit of major surgery for elderly lung cancer patients using observational data. Int. J. Epidemiol. 49, 1719–1729 (2020).

Paek, J. H. et al. Timing for initiation of sequential continuous renal replacement therapy in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 37, 239–247 (2018).

Li, C., Wang, H., Liu, N., Jia, M. & Hou, X. The effect of simultaneous renal replacement therapy on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for postcardiotomy patients with cardiogenic shock: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc Anesth. 33, 3063–3072 (2019).

Shirakabe, A. et al. Organ dysfunction, injury, and failure in cardiogenic shock. J. Intens. Care Med. 11, 26 (2023).

Mou, Z., He, J., Guan, T. & Chen, L. Acute kidney injury during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: VA ECMO versus VV ECMO. J. Intens. Care Med. 37, 743–752 (2022).

Schmidt, M. et al. Impact of fluid balance on outcome of adult patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Intens. Care Med. 40, 1256–1266 (2014).

Bridges, B. C. et al. Extracorporeal Life Support Organization guidelines for fluid overload, acute kidney injury, and electrolyte management. ASAIO J. 68, 611–618 (2022).

Pasin, L., Boraso, S. & Tiberio, I. Early initiation of renal replacement therapy in critically ill patients: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Anesthesiol. 19, 62 (2019).

Marants, R. et al. Renal perfusion during hemodialysis: intradialytic blood flow decline and effects of dialysate cooling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 30, 1086–1095 (2019).

Slessarev, M. et al. Continuous renal replacement therapy is associated with acute cardiac stunning in critically ill patients. Hemodial. Int. 23, 325–332 (2019).

Silversides, J. A. et al. Fluid balance, intradialytic hypotension, and outcomes in critically ill patients undergoing renal replacement therapy: a cohort study. Crit. Care 18, 624 (2014).

White, K. C. et al. Impact of continuous renal replacement therapy initiation on urine output and fluid balance: a multicenter study. Blood Purif. 52, 532–540 (2023).

Sansom, B. et al. The relationship between commencement of continuous renal replacement therapy and urine output, fluid balance, mean arterial pressure, and vasopressor dose. Crit. Care Resusc. 24, 259–267 (2022).

Wilson, M. R. et al. Inhibition of TNF receptor p55 by a domain antibody attenuates the initial phase of acid-induced lung injury in mice. Front. Immunol. 8, 128 (2017).

Murugan, R. et al. Associations between intensity of RRT, inflammatory mediators, and outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 926–933 (2015).

Al-Lamki, R. S. et al. TNFR1- and TNFR2-mediated signaling pathways in human kidney are cell type-specific and differentially contribute to renal injury. FASEB J. 19, 1637–1645 (2005).

Niewczas, M. A. et al. Circulating TNF receptors 1 and 2 predict ESRD in type 2 diabetes. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 507–515 (2012).

Funding

This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Research on Policy Planning and Evaluation from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (22AA2003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK and TT, as the first authors, and KW, as the corresponding author, were primarily responsible for the paper and managed the entire process including research design, data collection, data analysis as well as manuscript writing and revision. NI was engaged in research design, data analysis, and contributed to manuscript revision. ACO, DC, AJT and KMW contributed to manuscript writing and revision. KF was involved in research design, data collection, and manuscript revision. JAN contributed to the research design, manuscript writing, and manuscript revision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of Institute of Science Tokyo (M2000-788), which also waived the requirement for informed consent from patients due to the anonymization of the data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kubo, T., Takeuchi, T., Inoue, N. et al. Impact of early initiation of renal replacement therapy in patients on venoarterial ECMO using target trial emulation with Japanese nationwide data. Sci Rep 15, 1074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85109-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85109-9