Abstract

This study reports the synthesis and characterization of a novel CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 hybrid material through the state-of-the-art in-situ growth of the lead-free and non-toxic CsCu2I3 perovskite within the porous UiO-66(Ce)-NH2. The composite exhibits a high surface area with the CsCu2I3 nanostructures uniformly dispersed within the UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 framework. The host-guest CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 was considered as an effective and stable catalyst for the one-pot three-component copper(I)-catalyzed intermolecular alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) or click reaction. Under optimized conditions, utilizing water at room temperature, the nominal catalyst exhibited superior activity, outperforming its individual components. Remarkably, the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 catalyst demonstrated good recyclability and reusability over several catalytic runs. Mechanistic studies unveiled a synergistic cooperation between the CsCu2I3 and MOF, leading to the enhanced catalytic performance and improved stability of the perovskite. The developed multifunctional porous solid offers potential applications in catalysis and related fields, paving the way for innovative and sustainable organic synthesis and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Perovskites with the general formula ABX3 have garnered significant attention in recent years as semiconductors due to their remarkable performance in photovoltaic cells and other optoelectronic devices. This is attributed to their unique physical and chemical properties, their simple manufacturing and the ability to tune their characteristics. The most commonly studied perovskites, lead halide perovskites (APbX3), were first reported in the 20th century. However, the materials have limited use due to their poor stability and high toxicity1,2,3. Consequently, extensive research has focused on developing alternative perovskites with lower toxicity and/or higher efficiency.

Cu-based low-dimensional perovskites have shown promise as intrinsic earth-abundant scintillators, exhibiting high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY), high thermal stability, and lower toxicity4,5. However, the preparation of Cu perovskites faces several challenges, such as the need for capping or stabilizing agents. Additionally, the applications of Cu perovskites have been continuously emerging, but their catalytic performance has not been extensively explored6,7,8.

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are another class of heavily studied micro-/mesoporous crystalline materials9,10,11. MOFs are formed by metal ion units or clusters as nodes and organic linkers as connectors. These materials are characterized by their high crystallinity, high specific surface areas (up to 10,000 m2/g), large internal pore volumes (up to 90% free volume), and low density12. Due to these key features, MOFs have been extensively investigated for applications in gas storage/separation13,14, sensors15,16, catalysis17,18,19,20, photocatalysis21, and other areas.

UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 is an amino-functionalized analog of the well-known UiO-66 MOF22,23,24. This material exhibits several attractive properties, such as exceptional thermal and chemical stability, high porosity, high BET surface area, a relatively simple and mild preparation method, and versatile functionalization capabilities, making it a favorable candidate for various applications25,26,27. The amino groups can serve as anchoring/supporting sites for various functional groups, catalysts, or guest molecules, enabling diverse applications such as catalysis, gas storage/separation, and analytical processes25,28. Moreover, the incorporation of cerium as the most abundant rare-earth element renders this material a compelling candidate for practical applications29.

The integration of perovskite and MOF crystals through rational design can result in the formation of a new class of porous composite materials with enhanced structural features, improved stability, higher efficiency and activity rather than using the primary components6,30,31,32,33,34. CuAAC or “click” reaction, has been extensively studied for the synthesis of heterocycles used in various field of chemistry, biology, and material science35,36. Up to now, CuSO4·5H2O/β-cyclodextrin/sodium ascorbate37, Cu-metallopolymer38, Cu@UiO-67-IM (IM = imidazolium salt)39, saCu-x@mpgC3N440, MOF-derived Cu@N-C41, and Cu(I) complexes immobilized on multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNT)42 have been investigated as CuAAC catalysts. Nevertheless, despite the successful achievements, these systems often suffer from the need for additives or organic solvents, the use of high catalyst amounts, lack of reusability, and long reaction times, which limit their practical applications.

In this work, the hybridization of the cerium-based MOF, UiO-66(Ce)-NH2, with the lead-free, earth-abundant, and non-toxic CsCu2I3 perovskite43,44,45 to form the CsCu2I3@ UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 composite is reported. Using an in-situ growth method, the CsCu2I3 units are uniformly incorporated within the UiO-66-NH2 framework, with strong contact between the two components without pore blocking. The UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 can serve as a nanoscale scaffold, effectively stabilizing and spatially confining the growth of CsCu2I3 nanostructures, leading to precise control over their size and morphology.

The resulting CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 composite material was studied as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst for three-component click reaction. The catalytic performance of CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 surpassed that of its individual components and most reported catalysts. Notably, the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 catalyst demonstrated exceptional stability, allowing for facile recovery from the reaction media and efficient reuse without significant loss in catalytic activity. The enhanced catalytic performance was due to a combination effect between the CsCu2I3 and UiO-66(Ce)-NH2.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Chemical materials such as ammonium cerium(IV) nitrate ((NH4)Ce(NO3)6), terephthalic acid (BDC), 2-aminoterephthalic acid (BDC-NH2), N,Nʹ-dimethylformamide (DMF), cesium iodide, copper iodide, acetonitrile, sodium azide, benzyl halides, and phenylacetylenes were purchased from Merck and Sigma-Aldrich with high purity. UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 was prepared according to the previous procedures22. Synthesis of individual CsCu2I3 was adjusted from the literature43, as mentioned below.

Synthesis of CsCu2I3

In a glass vial, CuI (1.4 mmol) and CsI (0.70 mmol) were added to anhydrous acetonitrile (5 mL) and stirred for 4 h at 60 °C. The resulting yellow solution underwent controlled cooling to ambient temperature and subsequent filtration through a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) syringe filter (0.45 μm). Subsequently, diethyl ether (approximately 2 mL) was added dropwise as an antisolvent to the filtrate, leading to the formation of a white precipitate of CsCu2I3. Finally, the crystals were isolated by centrifugation.

Synthesis of UiO-66(Ce)-NH2

To synthesize UiO-66(Ce)-NH2, briefly, the process begins by dissolving BDC (70.8 mg, 0.426 mmol) in 2.5 mL of DMF (~ 10 mL glass vial). Then, 800 µL of a 0.533 M solution of (NH4)Ce(NO3)6 is added. The vial is sealed, and the mixture is stirred for 30 min at 100 °C. Thee sample is collected via centrifugation and washed three times with DMF and ethanol. After the final ethanol wash, the sample is left to soak in ethanol overnight. The solid is then collected by centrifugation, dried under vacuum at 70 °C for 1 h, and activated at 90 °C for 12 h to give UiO-66(Ce). For the solvent-assisted linker exchange (SALE) process, 32.63 mg of UiO-66(Ce), 72.46 mg of BDC-NH2 (0.4 mmol), and 10 mL of methanol are combined together. The solution is vortexed to ensure thorough mixing, and then sonicated for 5 min, with occasional checks to ensure no sample has settled to the bottom. The sample is then centrifuged and washed with DMF and ethanol, allowing it to soak in the fresh solvent for 30 min during each washing step. The collected sample is then dried under vacuum at 80 °C for 1 h and activated at 40 °C for 24 h.

CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2

The nanostructure was synthesized via antisolvent/inverse solvent infiltration method, following these steps: Copper iodide (CuI, 1.4 mmol) and cesium iodide (CsI, 0.70 mmol) were added to acetonitrile (5 mL) and stirred for 4 h at 60 °C. After cooling the mixture to room temperature, it was filtered through a PTFE filter. The filtered solution was then transferred to a glass vial containing activated UiO-66-NH2(Ce) (50 mg). The vial was capped and heated at 60 °C for 24 h. Then, the CsCu2I3 crystals were formed at room temperature by dropwise adding diethyl ether. The reaction was done to get the CsCu2I3@ UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 composite. As-synthesized CsCu2I3@ UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 composite was filtered and washed by acetonitrile and acetone. The collected crystals were dried in vacuum at 70 °C for 12 h to afford the light brown solid.

Click transformation

Benzyl halide (0.5 mmol), sodium azide (1 mmol), terminal alkyne (1 mmol), and catalyst (10 mg) were combined and stirred in aqueous medium (2 mL). After the completion of the reaction as monitored by TLC (n-hexane/ethyl acetate (4:1)), the catalyst was removed by centrifugation. With ethyl acetate the organic phase was extracted. The Na2SO4 removes water from the organic extract. Finally, recrystallization from a mixture of ethyl acetate and hexane yielded the pure product.

Reusability of the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 catalyst

Subsequent to the first run, the catalyst underwent thorough washing with ethyl acetate and acetone. Following the washing step, the catalyst was subjected to drying in an oven maintained at a temperature of 70 °C. Then, the catalyst was reused for the next cycle of the process.

Result and discussion

CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 characterization

Characterization of the CsCu2I3@Ce-UiO-66-NH2 composite was carried out using various techniques. PXRD patterns of CsCu2I3 (Figure S1), UiO-66(Ce) (Figure S2), UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 and CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 crystal structures are shown in Fig. 1. As shown in the Fig. 1, the crystallinity of UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 was remained intact after the growth of CsCu2I3 crystals. In the hybrid case, the two key peaks at 2θ values of ~ 7.2° and ~ 8.3° were observed, matching to (111) and (200) UiO-66 crystal facets22. The other characteristic peaks at approximately 12.1°, 17.1°, 22.3°, 25.4°, 25.8°, 29.9°, 34.6°, 35.6°, 43.4°, 43.7°, and 49.7o are respectively assigned to Miller indices of (220), (400), (511), (531), (600), (444), (800), (644), (933), (1000), and (880) of the UiO-66 structure. Notably, the PXRD pattern of the composite exhibits a strong characteristic peak of CsCu2I3 (PDF#45–0076) at about 43o (440 plan)46, which overlaps with the 1000 plan of the MOF. This provides a strong evidence for the formation of CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2. The absence of other characteristic peaks of CsCu2I3 is likely due to its small particle size and low loading amount within the UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 framework.

Figure 1. PXRD patterns of UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (bottom) and CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (top). The asterisk corresponds to (440) crystal plane of CsCu2I3.

In order to check the porosity of the sample, low pressure N2 adsorption-desorption experiments at 77 K were achieved (Fig. 2a). As depicted in Fig. 2, the N2 isotherms show a characteristic type I (IUPAC classification), which is an assigned feature of microporous MOFs47. The measured Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas and pore volume for UiO-66(Ce), UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 and CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 samples were calculated to be 850 m2 g− 1 (0.41 cm³/g), 440 m2 g− 1 (0.15 cm³/g) and ~ 200 m2 g− 1 (0.07 cm³/g), respectively. The observed decreases in surface area and pore volume are attributed to the incorporation of the amino linker and CsCu2I3, respectively. Additionally, nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) pore size distribution (PSD) analysis indicated smaller pore sizes (~ 0.9 nm) for the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 material compared to the parent MOFs (Fig. 2b), further confirming the growth of CsCu2I3 within the framework.

Figure 2a N2 sorption isotherms of UiO-66(Ce), UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 and CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2, and (b) pore size distribution of the different samples.

As shown in Fig. 3, the morphology of the materials was evaluated by FESEM. Accordingly, the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 retained the irregular octahedral morphology of the parent UiO-66 interconnected particles, with a size range of 80–300 nm22. As a result, the pristine framework is stable as remained undamaged during the composite synthesis.

Figure 3. SEM images of UiO-66(Ce) (a-c), UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (d-f), and CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (g-i).

Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDS) spectroscopy of CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (Figure S3) revealed the following elemental composition (wt%): C (21.68), N (5.33), O (18.37), Cu (0.87), Cs (1.03), and Ce (52.68). The EDS analysis confirmed the formation of CsCu2I3, showing a Cu/Cs molar ratio of approximately 2:1, consistent with the nominal structure. EDS mapping demonstrated uniform distribution of elements within the framework (Figure S4). Based on the characterization data, CsCu2I3 primarily forms within the MOF pores rather than as a core-shell structure on the exterior.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed to confirm the composite formation and to identify the Cu oxidation state in the composite (Figure S5). High-resolution Cu 2p3/2 spectra of as-synthesized CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 showed two contributions at 931.2 eV and 933.3 eV, both assigned to Cu(I)46. These results suggest that the MOF effectively protects Cu(I) from oxidation to Cu(II) under reaction conditions.

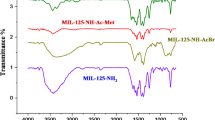

The FT-IR spectra of UiO-66(Ce), UiO-66(Ce)-NH2, and CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 provided information about the functional groups present in each material. UiO-66(Ce) is a material with Ce atoms coordinated with BDC organic ligands. Its FT-IR spectrum shows bands corresponding to carboxylate-Ce vibrations at 1547 and 1389 cm− 1 (Figure S6). UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 is obtained through a linker exchange method where amine groups as active sites are introduced into the material. The FT-IR spectrum of UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 shows characteristic bands related to N-H (3420 and 3360 cm− 1) and C-N (1259 cm− 1) vibrations, indicating the presence of amine groups in the material (Figure S7) 1. 1H NMR of the digested UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 approved the linker replacement (Figure S8). For CsCu2I3, the FT-IR spectrum reveals bands corresponding to the Cs/Cu-I at ~ 1500–1629 cm− 1 (Figure S9)48. The FT-IR spectrum of CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 shows a grouping of the characteristic bands of the individual components in the composite material, although with some peak shifts (Figure S10). Significantly, the amino-related peaks of UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 show reduced intensity and altered positions, suggesting strong interactions with metal ions. These changes provide compelling evidence that the amino groups serve as nucleation sites for the in situ growth of CsCu2I3 within the MOF structure.

Through careful analysis and comparison with reference spectra of the individual components, one can determine the presence and interactions of the different functional groups and components within the composite material. Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) in air demonstrated that the composite exhibits higher thermal stability than both UiO-66(Ce) and UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (Figure S11). Mass loss observed below 200 °C is attributed to the removal of solvent trapped in the framework. The data are consistent with the expected characteristics of such a composite, where the porous UiO-66 provides a high surface area support and the perovskite component contributes to the overall structure and functionality.

Evolution of catalytic activity

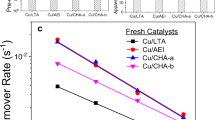

To examine the catalytic activity of the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2, the one-pot three-component CuAAC reaction was investigated. The reaction conditions were optimized using benzyl chloride, sodium azide, and phenylacetylene as the model substrates (Table 1). Table 1 shows the effect of different catalysts, solvents, and temperatures on the CuAAC reaction. The results indicate that water was the most suitable reaction medium as the green solvent, affording the highest yield (90%) of the product in 45 min at room temperature using the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 (Table 1, entry 1). The reaction could be also completed within 40 min in water at 50 °C, reaching that of 90% product yield (entry 2). Other solvents, such as ethyl acetate, ethanol, acetonitrile, and ethanol/water resulted in lower yields and longer reaction times (entries 3–6). When the pristine UiO-66-NH2 was used as the catalyst (entry 7), no desired product was observed. The CsCu2I3 (entry 8 versus entry 1) also gave a high yield of 80% under the optimum condition, but the catalyst could not be reused effectively. In comparison, the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 revealed good recyclability and stability, as evident from entry 1, where the catalyst was reused with only a minimal loss in its catalytic activity after 5 cycles. CuI as catalyst afforded only 46% of product yield (entry 9). BDC-NH2 and (NH4)Ce(NO3)6 precursors as catalysts gave negligible product yield (entries 10 and 11). The composite catalyst demonstrated superior performance compared to individual components, likely due to synergistic effects and improved stability. The composite contains well-dispersed and stable Cu(I) species in the form of CsCu2I3.

Then, the optimal reaction condition was explored for the synthesis of 1,4-diphenyl-1,2,3-triazole derivatives (Table 2), affording the high yields of 87–92% in 25–70 reaction times with turnover frequencies (TOF) of 272–806 h− 1.

The stability of the catalyst was further evaluated by recovering it after being reused through FT-IR (Figure S12), PXRD (Figure S13), SEM (Figure S14), and XPS (Figure S15). The results demonstrated that the recovered catalyst retained its structural, compositional, and morphological features comparable to the fresh catalyst, highlighting its effectiveness and robustness in the reaction. The Cu 2p and Ce 3d XPS results also suggested that Cu(I) and Ce(IV) are predominant in the composite (Figure S15). In addition, leaching experiment was considered to ensure the integrity of our catalyst system. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) of the filtered reaction solution showed negligible Cu content in the filtered solution (< 0.07 ppm). In addition, UV-Vis spectroscopy of the reaction solution showed no characteristic absorbance peaks of the BDC-NH2 linker. Furthermore, a hot filtration test was conducted by removing the solid catalyst once the product yield reached 25%. The reaction mixture was monitored for an additional 2 h after catalyst removal, during which no further product formation was observed, confirming the heterogeneous nature of catalysis.

The proposed reaction mechanism, as illustrated in Fig. 4, has been the subject of numerous studies aimed at explaining its pathways39,40,49,50,51. The process begins with the coordination of the alkyne to the Cu(I) center of the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2, acting as a π-ligand, which consequently enhances the acidity of the C-H bond. After deprotonation, a σ,π-di(copper) acetylide complex (I) is succeeded. Simultaneously, the benzyl halide and sodium azide undergo a reaction, generating a benzyl azide intermediate that binds to the Cu(I) center, resulting in the formation of a dicopper intermediate. The acetylide-azide reaction arises via an oxidative addition step, yielding a six-membered intermediate (II), which subsequently undergoes a reductive elimination process to give the Cu(I)-triazolide intermediate (III). The final triazole product is formed through the protonation process, thereby regenerating the catalyst and completing the catalytic cycle. It should be noted that the catalytic activity predominantly occurs within the pores of the composite rather than on its surface. The employed substrates (with Kinetic diameter ~ 1 nm) can diffuse into pores (please see Fig. 2) based on their size. Also, when 9,10-bis(bromomethyl)anthracene was used as a bulker starting material, the reaction yielded negligible product. This observation can settle the size-selective nature of the catalyst.

Figure 4. Suggested reaction pathways of the click reaction over the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 catalyst.

Table 3 provides a comparison of the current work (entry 9) with the other reported catalytic systems for three-component click reaction of NaN3, phenyl acetylene, and benzyl bromide/chloride. The results reveals clearly that the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 includes some advantages over the previously reported methods, affording a high product yield (90%) under mild conditions (room temperature, water as the green solvent, and shorter reaction time) and the low dosage of the catalyst with an excellent TOF of 438 h− 1.

Conclusion

In this work, a novel CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 composite was successfully synthesized by incorporating the lead-free and non-toxic CsCu2I3 perovskite nanostructures within the porous UiO-66(Ce)-NH2. The catalytic performance of the CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 was investigated in the one-pot three-component click reaction. The composite catalyst revealed superior activity, affording the desired triazole products in 87–92% yields within 25–70 min (TOFs 272–806 h− 1). This catalytic activity outperformed the pristine CsCu2I3 and UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 constituents, as well as the most reported catalytic systems. Remarkably, the catalyst exhibited excellent reusability, with minimal loss of activity over multiple catalytic cycles. The developed CsCu2I3@UiO-66(Ce)-NH2 hybrid material represents a promising reusable and efficient heterogeneous catalyst for organic transformations, particularly three component click reactions. The synergistic effects arising from the integration of perovskite and MOF components offer opportunities for designing advanced and stable materials with tailored properties and functionalities for various applications in catalysis, photocatalysis, energy, and related fields.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mitzi, D. B. & Introduction: Perovskites Chem. Rev. 119, 3033–3035, (2019).

Chowdhury, T. A. et al. Stability of perovskite solar cells: issues and prospects. RSC Adv. 13, 1787–1810 (2023).

Du, F. et al. Improving the stability of halide perovskites for photo-, electro-, photoelectro-chemical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312175 (2024).

Yang, S., Tang, Z., Qu, B., Xiao, L. & Chen, Z. Crown-assisted CsCu2I3 growth and trap passivation for perovskite light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16, 20776–20785 (2024).

Lu, Y., Li, G., Fu, S., Fang, S. & Li, L. CsCu2I3 nanocrystals: growth and structural evolution for tunable light emission. ACS Omega. 6, 544–552 (2021).

Daliran, S., Khajeh, M., Oveisi, A. R., Albero, J. & García, H. CsCu2I3 nanoparticles incorporated within a mesoporous metal–organic porphyrin framework as a catalyst for one-pot click cycloaddition and oxidation/Knoevenagel tandem reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14, 36515–36526 (2022).

Tabari, T., Kobielusz, M., Singh, D., Yu, J. & Macyk, W. Cobalt-/Copper-containing perovskites in oxygen evolution and reduction reactions. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 1, 2207–2216 (2023).

Prašnikar, A., Dasireddy, D. B. C., Likozar, B. & V. & Scalable combustion synthesis of copper-based perovskite catalysts for CO2 reduction to methanol: reaction structure-activity relationships, kinetics, and stability. Chem. Eng. Sci. 250, 117423 (2022).

Xiao, C., Tian, J., Chen, Q. & Hong, M. Water-stable metal–organic frameworks (MOFs): rational construction and carbon dioxide capture. Chem. Sci. 15, 1570–1610 (2024).

Gagliardi, L. & Yaghi, O. M. Three future directions for metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Mater. 35, 5711–5712 (2023).

Daliran, S. et al. Metal–organic framework (MOF)-, covalent-organic framework (COF)-, and porous-organic polymers (POP)-catalyzed selective C–H bond activation and functionalization reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 7810–7882 (2022).

Li, D. et al. Advances and applications of Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) in emerging technologies: a comprehensive review. Glob Chall. 8, 2300244 (2024).

Li, Y., Wang, Y., Fan, W. & Sun, D. Flexible metal–organic frameworks for gas storage and separation. Dalton Trans. 51, 4608–4618 (2022).

Li, H. et al. Porous metal-organic frameworks for gas storage and separation: Status and challenges. EnergyChem 1, 100006, (2019).

Kreno, L. E. et al. Metal–organic framework materials as chemical sensors. Chem. Rev. 112, 1105–1125 (2012).

Sohrabi, H. et al. Metal-organic frameworks (MOF)-based sensors for detection of toxic gases: a review of current status and future prospects. Mater. Chem. Phys. 299, 127512 (2023).

Lee, J. et al. Metal–organic framework materials as catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1450–1459 (2009).

Jiao, L., Wang, J. & Jiang, H. L. Microenvironment modulation in metal–organic framework-based catalysis. Acc. Mater. Res. 2, 327–339 (2021).

Dhakshinamoorthy, A., Navalon, S., Asiri, A. M. & Garcia, H. Metal organic frameworks as solid catalysts for liquid-phase continuous flow reactions. Chem. Commun. 56, 26–45 (2020).

Oudi, S., Oveisi, A. R., Daliran, S., Khajeh, M. & Teymoori, E. Brønsted-Lewis dual acid sites in a chromium-based metal-organic framework for cooperative catalysis: highly efficient synthesis of quinazolin-(4H)-1-one derivatives. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 561, 782–792 (2020).

Oudi, S. et al. Straightforward synthesis of a porous chromium-based porphyrinic metal-organic framework for visible-light triggered selective aerobic oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 611, 117965 (2021).

Son, F. A., Atilgan, A., Idrees, K. B., Islamoglu, T. & Farha, O. K. Solvent-assisted linker exchange enabled preparation of cerium-based metal–organic frameworks constructed from redox active linkers. Inorg. Chem. Front. 7, 984–990 (2020).

Jacobsen, J., Ienco, A., D’Amato, R., Costantino, F. & Stock, N. The chemistry of Ce-based metal–organic frameworks. Dalton Trans. 49, 16551–16586 (2020).

Lammert, M. et al. Cerium-based metal organic frameworks with UiO-66 architecture: synthesis, properties and redox catalytic activity. Chem. Commun. 51, 12578–12581 (2015).

Dai, S. et al. Room temperature design of Ce(IV)-MOFs: from photocatalytic HER and OER to overall water splitting under simulated sunlight irradiation. Chem. Sci. 14, 3451–3461 (2023).

Armoon, A., Khajeh, M., Oveisi, A. R., Ghaffari-Moghaddam, M. & Rakhshanipour, M. Effective adsorption of methyl orange dye from water samples over copper(II) Schiff-base complex-immobilized cerium-based metal-organic framework. J. Mol. Struct. 1304, 137612 (2024).

Ghadim, E. E., Walker, M. & Walton, R. I. Rapid synthesis of cerium-UiO-66 MOF nanoparticles for photocatalytic dye degradation. Dalton Trans. 52, 11143–11157 (2023).

Jalalzaei, F., Khajeh, M., Kargar-Shouroki, F. & Oveisi, A. R. Oxime-functionalized cerium-based metal–organic framework for determination of two pesticides in water and biological samples by HPLC method. J. Nanostructure Chem. 14, 95–112 (2024).

Shen, C. H. et al. Cerium-based metal–organic framework nanocrystals interconnected by carbon nanotubes for boosting electrochemical capacitor performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13, 16418–16426 (2021).

Cao, J., Tang, G. & Yan, F. Applications of emerging metal and covalent organic frameworks in perovskite photovoltaics: materials and devices. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2304027, (2024).

Zhang, J. et al. Zr-metal–organic framework based cross-layer-connection additive for stable halide perovskite solar cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 628, 157339 (2023).

Huang, J. N. et al. Efficient encapsulation of CsPbBr3 and au nanocrystals in mesoporous metal–organic frameworks towards synergetic photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 10, 25212–25219 (2022).

Nie, W. & Tsai, H. Perovskite nanocrystals stabilized in metal–organic frameworks for light emission devices. J. Mater. Chem. A. 10, 19518–19533 (2022).

Qiao, G. Y. et al. Perovskite quantum dots encapsulated in a mesoporous metal–organic framework as synergistic photocathode materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 14253–14260 (2021).

Haldón, E., Nicasio, M. C. & Pérez, P. J. Copper-catalysed azide–alkyne cycloadditions (CuAAC): an update. Org. Biomol. Chem. 13, 9528–9550 (2015).

Héron, J. & Balcells, D. Concerted cycloaddition mechanism in the CuAAC reaction catalyzed by 1,8-naphthyridine dicopper complexes. ACS Catal. 12, 4744–4753 (2022).

Shin, J. A., Lim, Y. G. & Lee, K. H. Copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition reaction in water using cyclodextrin as a phase transfer Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 77, 4117–4122 (2012).

Joshi, S., Yip, Y. J., Türel, T., Verma, S. & Valiyaveettil, S. Cu–tetracatechol metallopolymer catalyst for three component click reactions and β-borylation of α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. Chem. Commun. 56, 13044–13047 (2020).

Hu, Y. H., Wang, J. C., Yang, S., Li, Y. A. & Dong, Y. B. CuI@UiO-67-IM: a MOF-based bifunctional composite triphase-transfer catalyst for sequential one-pot azide–alkyne cycloaddition in water. Inorg. Chem. 56, 8341–8347 (2017).

Vilé, G. et al. Azide-alkyne click chemistry over a heterogeneous copper-based single-atom catalyst. ACS Catal. 12, 2947–2958 (2022).

Wang, Z., Zhou, X., Gong, S. & Xie, J. MOF-derived Cu@N-C catalyst for 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. Nanomaterials 12, 1070 (2022).

Librando, I. L. et al. Synthesis of a bovel series of Cu(I) complexes bearing alkylated 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane as homogeneous and carbon-supported catalysts for the synthesis of 1- and 2-substituted-1,2,3-triazoles. Nanomaterials 11, 2702 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. Solution-processed one-dimensional CsCu2I3 nanowires for polarization-sensitive and flexible ultraviolet photodetectors. Mater. Horiz. 7, 1613–1622 (2020).

Lin, R. et al. All-inorganic CsCu2I3 single crystal with High-PLQY (≈ 15.7%) intrinsic white-light emission via strongly localized 1D excitonic recombination. Adv. Mater. 31, 1905079 (2019).

Yan, S. S. et al. Enhanced optoelectronic performance induced by ion migration in lead-free CsCu2I3 single-crystal microrods. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 14, 49975–49985 (2022).

Mo, X. et al. Highly-efficient all-inorganic lead-free 1D CsCu2I3 single crystal for white-light emitting diodes and UV photodetection. Nano Energy. 81, 105570 (2021).

Oveisi, A. R., Daliran, S. & Peng, Y. in Catalysis in Confined Frameworks (eds Garcia H. & Dhakshinamoorthy A.) Ch. 3, 97–126, Wiley, (2024).

Archana, K. M., Yogalakshmi, D. & Rajagopal, R. Application of green synthesized nanocrystalline CuI in the removal of aqueous Mn(VII) and Cr(VI) ions. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 522, (2019).

Nemati, F., Heravi, M. M. & Elhampour, A. Magnetic nano-Fe3O4@TiO2/Cu2O core–shell composite: an efficient novel catalyst for the regioselective synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles using a click reaction. RSC Adv. 5, 45775–45784 (2015).

Mekhzoum, M. E. M., Benzeid, H., Qaiss, A. E. K., Essassi, E. M. & Bouhfid, R. Copper(I) confined in interlayer space of montmorillonite: a highly efficient and recyclable catalyst for click reaction. Catal. Lett. 146, 136–143 (2016).

Ayouchia, B. E., Bahsis, H., Anane, L., Domingo, H., Stiriba, S. E. & L. R. & Understanding the mechanism and regioselectivity of the copper(I) catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction between azide and alkyne: a systematic DFT study. RSC Adv. 8, 7670–7678 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the University of Zabol (Grant numbers: UOZ-GR-8175, UOZ-GR-9381, and UOZ-GR-4188). Authors also thank the Lorestan University for the support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.R.K., A.R.O., E.S., S.D., and M.K. considered the experiments presented herein. L.R.K. synthesized and characterized the catalyst under supervision of S.D. and E.S. The organic reactions carried out by L.R.K. A.R.O. and E.S. supervised the project. S.D. and M.K. wrote the initial draft of the paper with inputs and corrections from all co-authors. A.R.O. E.S. and S.D. finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kahkhaie, L.R., Oveisi, A.R., Sanchooli, E. et al. Lead free perovskite integrated metal organic framework as heterogeneous catalyst for efficient three component click reaction. Sci Rep 15, 7284 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85204-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85204-x