Abstract

Percutaneous transthoracic puncture of small pulmonary nodules is technically challenging. We developed a novel electromagnetic navigation puncture system for the puncture of sub-centimeter lung nodules by combining multiple deep learning models with electromagnetic and spatial localization technologies. We compared the performance of DL-EMNS and conventional CT-guided methods in percutaneous lung punctures using phantom and animal models. In the phantom study, the DL-EMNS group showed a higher technical success rate (95.6% vs. 77.8%, p = 0.027), smaller error (1.47 ± 1.62 mm vs. 3.98 ± 2.58 mm, p < 0.001), shorter procedure duration (291.56 ± 150.30 vs. 676.44 ± 246.12 s, p < 0.001), and fewer number of CT acquisitions (1.2 ± 0.66 vs. 2.93 ± 0.98, p < 0.001) compared to the traditional CT-guided group. In the animal study, DL-EMNS significantly improved technical success rate (100% vs. 84.0%, p = 0.015), reduced operation time (121.36 ± 38.87 s vs. 321.60 ± 129.12 s, p < 0.001), number of CT acquisitions (1.09 ± 0.29 vs. 2.96 ± 0.73, p < 0.001) and complication rate (0% vs. 20%, p = 0.002). In conclusion, with the assistance of DL-EMNS, the operators got better performance in the percutaneous puncture of small pulmonary nodules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amidst the rising utilization of computed tomography (CT) for lung cancer screening, a noteworthy surge in the identification of pulmonary nodules has occurred1. Small pulmonary nodules with a diameter ≤ 10 mm (sub-centimeter pulmonary nodules, SCPNs) are observed in approximately 14.5% of the screened population, of which 55.5% of the detected lung cancers were SCPNs2. The utilization of CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsies (PCNB) and CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic thermal ablation has become widespread for the diagnostic and therapeutic management of pulmonary nodules3,4,5. Nonetheless, the percutaneous transthoracic puncturing of small pulmonary nodules remains a challenging endeavor, even with the integration of advanced CT technology. The inherent limitations in the orientation of imaging planes for needle trajectory, compounded by the confined gantry bore dimensions of CT systems and the absence of real-time imaging capabilities, collectively contribute to the technical intricacies of CT-guided percutaneous lung punctures for small pulmonary nodules. Consequently, the diagnostic precision of CT-guided PCNB for small pulmonary nodules exhibits significant variability, with reported accuracies ranging from 52–90%6,7,8,9.

Electromagnetic guidance system has been developed to provide guidance for percutaneous pulmonary nodule puncture10. By establishing a comprehensive magnetic field around the patient, this system precisely delineates the sensor’s spatial coordinates within it. These coordinates are seamlessly integrated into existing CT images, providing a clear visual correlation between the sensor’s position and the surrounding anatomy. This technology is validated as secure, feasible, and time-efficient. Nonetheless, the current system, optimized for electromagnetic navigational bronchoscopy, presents certain operational complexities. It solely visualizes needle position and orientation in two-dimensional CT slices, lacking three-dimensional anatomical representation11. Consequently, a more streamlined and intuitive guidance approach for transthoracic percutaneous puncture of small pulmonary nodules is urgently needed.

Deep learning algorithms have shown great potential in medical image analysis tasks, including pulmonary nodule detection12, breast cancer diagnosis13, cerebral hemorrhage segmentation14, and medical image reconstruction and registration15,16. Previous studies have also demonstrated the ability of deep learning algorithms to automate the segmentation of anatomical structures and assist in surgical planning17. Combining deep learning algorithms and electromagnetic needle tracking techniques has great potential in providing very accurate needle targeting of small pulmonary nodules. However, the application of deep learning algorithms to facilitate percutaneous lung puncture remains unclear.

In this study, we developed a novel deep-learning based electromagnetic navigation system (DL-EMNS) to assist percutaneous transthoracic puncture for small pulmonary nodules. The technical reliability and effectiveness of the proposed DL-EMNS were evaluated through phantom and animal experiments.

Materials and methods

All current research methods were carried out under guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. All experimental procedures involving animals were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the IACUC of The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No. 2021842).

Development of DL-EMNS

By combining multiple deep learning models with spatial localization technologies, the proposed DL-EMNS provides operators with the detailed information of patient’s three-dimensional (3D) anatomy structures, the real-time position of the needle, and the virtual puncture trajectory.

The DL-EMNS system consists of a control system, a magnetic field generator, three patches, a sensor, and a monitor (Fig. 1). The performance of DL-EMNS mainly contains two steps: pre-operative preparation step and intra-operative navigation step, as shown in Fig. 2A. The first includes segmentation of thoracic organs and puncture trajectory planning based on multiple deep learning models. The second includes localization of positioning patches and real-time tracking based on electromagnetic technology. The whole navigation system is shown in Fig. 2B.

Preparation step

(A) 3D reconstruction of thoracic structures. Lung nodules and thoracic structures, including lobes, bronchus, vessels, chest wall, and bones, were automatically segmented and reconstructed using deep learning-based networks. The algorithm has been proven effective in assisting lung segmentectomy in a short time frame18. The 3D models can directly display the thoracic structures and the target lesion. Supplemental Materials Methods-1 provides more detailed information.

(B) Puncture trajectory planning. Once the puncture point on the body’s surface is chosen, the system will automatically create a virtual puncture path by connecting the selected puncture point with the nodule. This allows real-time visualization to determine if there are obstructions such as ribs or scapulae along the puncture path, as well as important blood vessels, trachea, etc., thereby avoiding puncture failure or complications. It will also continuously provide real-time distance feedback between the puncture needle and the nodule throughout the entire puncture procedure.

Navigation step

In the prior art, manual marking of internal or external feature points is generally required for registering preoperative images and intraoperative patient coordinates, resulting in inadequate puncture accuracy19. We novelly adopt positioning patches with distinct characteristics to establish the coordinate mapping relationship in real-time. Positioning patches are sensors fixed on the patient’s surface for real-time tracking of the patient’s posture. Three positioning patches with different shapes were involved in the system. An efficient and accurate localization algorithm of positioning patches was developed to rapidly align the image coordinate system with the patient’s physical coordinate system. The localization of positioning patches was predicted from coarse to fine. A ResUnet model was introduced to coarsely segment and detect the patch centers. The coarse center coordinates were then input to a fine segmentation model, returning the final center coordinates and segmentation labels of the positioning patches. The segmentation results were used for location confirmation and graphic visualization, and the fine patch center positions served as the fixed image reference coordinate system (Fig. 2C). More information was provided in Supplemental Materials Methods-2.

Operation process

At the beginning of the operation, the subject is placed on a magnetic field generator, and three patch sensors were fixed on its skin in a triangle shape covering the nodule. The subject is subsequently positioned on a CT scanner (Siemens SOMATOM Perspective), then its CT images were acquired to reconstruct and visualize the nodules, ribs, bronchus, and vessels. The puncture trajectories were automatically planned in the 3D model as descripted before.

During the procedure, the physical space of the subject was mapped to the preoperative image space based on the relationship of the three fixed sensors on both coordinate systems under the positioning of the electromagnetic device. The puncture site was decided with the assistance of the guidance system. When the operator positioned the needle tip at the surface of the phantom or animal’s thorax, the system automatically provided a simulated puncture path, indicating whether there were ribs or major blood vessels along the path and showing the distance from the needle tip to the target. As the operator moved the needle tip across the surface of the phantom or animal’s thorax, the simulated puncture path was updated in real-time. This allowed the operator to choose the puncture site based on factors such as distance to the target and the presence of obstacles.

Operators then conducted the transthoracic percutaneous lung puncture under the guidance of virtual insertion planning. When the needle reaches the nodule on the real-time guided image, a CT scan was then conducted for evaluation. If the needle tip reached the nodule, the operation was completed. If the needle tip did not reach the nodule, another deep-learning based 3D reconstruction, localization of positioning patches and puncture trajectory planning was conducted again according to the latest CT images. The procedure process is shown in Fig. 2D.

Technical flow chart of the DL-EMNS. (A) The technical flow chart of pre-operative preparation step and the intra-operative navigation step. In the first step, after a CT scan, images were segmented and reconstructed by deep learning-based approaches. In the second step, the real coordinate system in the magnetic field is fused with the three-dimensional reconstructed image, enabling the real-time display of the puncture needle, thoracic structures, and target nodules in the virtual image, thereby indicating the position of the puncture needle within the thoracic cavity. (B) Schematic diagram of DL-EMNS. (C) Schematic diagram of magnetic navigation system and coordinate matching. (D) schematic diagram of the operation process.

Phantom study

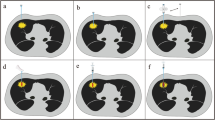

Three customized thoracic phantoms were used to validate the accuracy of the DL-EMNS, as shown in Fig. 3A-C. The “skin”, “ribs”, “vessels”, “bronchus”, and “nodules” of the phantoms were made from different materials, which could be distinguished on CT images (Fig. 3D). Each side of the “chest cavity” of each phantom is equipped with 3 nodules. The nodule sizes of the three phantoms are 6, 8, and 10 millimeters, respectively. Five doctors used DL-EMNS and traditional methods to simulate puncture on the nodules of these three phantoms respectively, with a wash period of 2 weeks (Fig. 3E). After more than five unsuccessful attempts at reaching the target, the operator’s confidence is often lost, and the procedure is then considered a failure. More information was provided in Figure S1.

In vivo animal study

An animal study was conducted to further evaluate the performance of the DL-EMNS in vivo, as shown in Fig. 3F and Figure S2. Nine Bama pigs, including four boars and five sows, with weights ranging from 19.5 kg to 35 kg, were used in the animal experiment. All experimental animals were obtained from qualified suppliers, ensuring compliance with ethical standards and regulatory requirements. The sex of the animals had no effect on the test results.

The animals were randomly assigned to either the DL-EMNS group (n = 6) or the traditional CT-guided group (n = 3). The Bama pigs were intubated after the induction of anesthesia, and maintained with orotracheal intubation during the operation. To mimic a small lung nodule, 0.1 ml of tissue adhesive (B. Braun Surgical SA) mixed with 0.1 ml of iohexol was randomly injected into the pig’s lung parenchyma under CT guidance, as we described before20. Three doctors used traditional methods and DL-EMNS to simulate puncture on the nodules of these nine pigs respectively (Fig. 3G). Six pigs underwent four punctures per side of the thoracic cavity. Two pigs, due to their smaller body weight (and consequently smaller thoracic cavities), received three punctures per side. One pig had four punctures on the left side and five punctures on the right side. After the experiments were completed, the pigs were sacrificed by injecting 2 mmol/kg of potassium chloride to induce asystole.

The phantom study and animal study. (A) The appearance of the customized thoracic phantom. (B) The customized phantom after removing the “skin”. (C) The internal structure and stimulated nodules (blue arrow). (D) The CT cross-sectional view of the simulated nodules (blue arrow) during puncture. (E) Design of the phantom study. Five doctors used traditional CT guidance way and DL-EMNS to simulate puncture on three models, respectively. (F) The process of animal study. After general anesthesia and tracheal intubation, the experimental animals lay on their side on the CT bed with magnetic navigation coil. The doctors performed percutaneous punctures of the nodules under the guidance of DL-EMNS or traditional CT. (G) Shows the schematic diagram of animal experiment. Three doctors performed traditional and DL-EMNS punctures on nine pigs, respectively.

Evaluation criteria

Technical success is defined as when the needle tip touched the nodule. On the contrary, if there is a technical malfunction or other reason (such as pneumothorax, hemothorax) during the procedure that prevents the operation from being completed, it is defined as a technical failure. Error is defined as the spatial distance between the center of the simulated nodule and the needle tip measured on the CT scan. It is used to evaluate the accuracy of needle placement. Additionally, the procedure duration (time from the start of the puncture until the nodule was reached or the operation ended) and the total number of CT acquisitions were recorded. For the animal study, complications such as hemothorax and pneumothorax were recorded.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 21.0). Continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. A two-sided p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Performance of DL-EMNS in the phantom study

In the phantom study, five physicians performed 90 “transthoracic percutaneous pulmonary punctures” on three phantoms, with 45 punctures using traditional CT guidance, and 45 punctures using DL-EMNS.

The DL-EMNS significantly improved the performance of the punctures, with a higher technical success rate compared to the traditional CT-guided group (95.6% vs. 77.8%, p = 0.027), as shown in Fig. 4A. Puncture success rates showed improvement across all nodule sizes. Particularly noteworthy was the marked enhancement in success rates observed specifically among 6 mm nodules (Fig. 4B). Of the 5 participating physicians, 4 demonstrated an improvement in puncture success rates upon integrating DL-EMNS into their procedures, while one physician (Doctor C) experienced a marginal decrease in success rate (Fig. 4C).

Additionally, as shown in Fig. 4D and E, the error was smaller in the DL-EMNS assisted group (2 mm, [0–2]) than in the traditional CT-guided group (4 mm, [2–4]) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, in the puncture of three nodules, the DL-EMNS system significantly shortened the puncture time (291.6 ± 150.3 s vs. 676.4 ± 246.1 s, p < 0.001) and reduced the number of CT acquisitions (1.2 ± 0.66 for the DL-EMNS vs. 2.93 ± 0.98 scans for the traditional CT-guided group, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4F-I).

Performance of DL-EMNS in the animal study

In the animal study, a total of 69 nodules were prepared with an average size of 9.7 ± 2.8 mm. 25 nodules were punctured under traditional CT guidance, while 44 nodules were punctured under DL-EMNS guidance. There was no significant difference in nodule size between the two groups (9.32 ± 2.78 mm vs. 9.39 ± 2.14 mm, p = 0.912, Fig. 5A).

Compared to the traditional CT-guided group, the DL-EMNS assisted punctures showed a higher success rate (100% vs. 84%, p = 0.015) in all three participated operators (Fig. 5B-C).

Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5D-E, the DL-EMNS system significantly shortened the puncture time (121.40 ± 38.97 s vs. 321.60 ± 129.10 s, p < 0.001) and reduced the number of required CT acquisitions (1 [1, 1] vs. 3 [2, 3], p < 0.001). No pneumothorax or hemothorax were observed in the DL-EMNS assisted group, while in the traditional CT-guided group, the incidence of complications was 20.0% (5/25), with two cases of pneumothorax, two cases of hemothorax, and one case of both pneumothorax and hemothorax (Fig. 5F).

Discussion

In this study, we introduced a novel deep learning based electromagnetic navigation system for percutaneous transthoracic puncture of small pulmonary nodules. Implementation of the DL-EMNS significantly improved the accuracy of needle positioning, reduced the CT acquisitions in a series of phantom and animal studies. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use deep learning algorithms to assist percutaneous pulmonary puncture for small pulmonary nodules.

Accurate needle placement is a vital factor in ensuring the success of CT image-guided percutaneous interventions. Incorrect needle positioning can result in wasted time, unnecessary X-ray exposure, adverse events, and various failures, such as obtaining non-diagnostic biopsy samples or incomplete ablation. The outcome of the CT-guided intervention can be greatly influenced by both its complexity and the individual skill of the physician, especially when the lesion is very small or an out-of-plane trajectory is necessary to achieve the anatomically safest route. Studies have shown that the smaller the nodule, the lower the success rate and the higher the complication rate21,22. As shown in our phantom and animal study, the technical success rate in the traditional group for percutaneous puncture of small pulmonary nodules was 77.8% and 84%, respectively, which is similar in previous studies23. This is because traditional CT-guided percutaneous lung puncture is performed free-handed, and the puncture site is determined by a positioning grid, which relies heavily on the operator’s experience22. Continual adjustment of the needle’s direction and depth can prolong the procedure time and increase the risk of complications, while repeated CT scans increase radiation exposure to patients24,25.

Several guidance and navigation systems including electromagnetic, optical, or hybrid tracking of devices during interventions have been introduced for more accurate and reproducible puncture results26,27,28. Electromagnetic navigation systems have demonstrated significant potential in facilitating the manipulation of puncture probes with enhanced flexibility and ease. These systems typically consist of a field generator that generates an electromagnetic field, alongside sensors capable of measuring the magnetic field strength, registering their position and orientation relative to the field generator. The sensors are arranged in a tetrahedral configuration of coils. Their compact size allows for integration into various tools, including needles. With a technical accuracy of 1.5 mm for position and 0.4° for orientation, electromagnetic navigation systems offer precise tracking capabilities. The electromagnetic navigation system has been proven to be effective and safe for CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy of peripheral lung lesions29. The system allows users with no prior experience of the system to perform faster and more accurate CT-guided biopsies with out-of-plane trajectories30. Virtual electromagnetic tracking demonstrates a remarkable level of accuracy in needle placement, offering the potential to decrease both time and radiation exposure when compared to conventional CT techniques for small lesion biopsies31.

The highlight of our proposed DL-EMNS is the combination of deep learning models with spatial localization technologies. Automatic detection, segmentation, and reconstruction of lesions and anatomical structures are implemented by the involved deep-learning method, which can greatly shorten the operation time. Real-time tracking of the needle during the entire procedure significantly improves accuracy with the guidance of automatic puncture path planning. Additionally, innovative positioning patches work as sensors to track the real-time position of the patient and serve as external feature points for automatic and efficient registration of preoperative image coordinate system and intraoperative patient spatial coordinate system. The combination of deep learning and electromagnetic technology improves puncture accuracy and reduces the number of CT acquisitions compared to traditional CT-guided approach, especially when the nodule is small or an out-of-plane trajectory is necessary to achieve the anatomically safest route.

Several limitations are evident in this study. Firstly, the reliance on animal and phantom experiments falls short of fully replicating human conditions. Although this study employs nodules with consistent shape and density to isolate the effects of size variations, we recognize that real-world nodules in the human lung exhibit diverse morphologic and density characteristics. Future investigations could expand on this work by incorporating nodules of varied shapes and densities, which would provide additional insights into the robustness of the proposed methodology. Secondly, the absence of breathing artifacts in the phantoms used in our study represents a significant limitation. Puncturing subcentimetric nodules in human lungs is more complex than described in our study due to the patient’s conscious state, physical movements, and intricate respiratory patterns, which can interfere with the needle trajectory and make the puncture technically challenging. Additionally, the need for multiple needle replacements posts initial puncture, such as for biopsy or ablation procedures, introduces heightened risks of displacement, bleeding, and pneumothorax. To address these gaps, our next endeavor will encompass a randomized controlled clinical study, aimed at robustly validating the feasibility of DL-EMNS in pulmonary nodule puncture. Concurrently, we are committed to the development of integrated biopsy and ablation needles equipped with magnetic navigation sensors. We are also in the process of designing a puncture robot based on DL-EMNS, aiming to minimize the impact of hand tremors during the puncture procedure. This design aims to make the puncture process simpler and more precise. Through these strategic advancements, we aspire to enhance the precision and safety of our approach, yielding substantial clinical benefits.

In conclusion, our study developed a pulmonary puncture navigation system by applying a deep learning approach. We demonstrated the system’s capability for improving the accuracy of needle positioning, as well as reducing operation time, total number of CT acquisitions and complications. Its effectiveness in clinical practice still requires a large sample randomized controlled trial to verify.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, FL.Y. and XF.C., upon reasonable request.

References

Oudkerk, M., Liu, S., Heuvelmans, M. A., Walter, J. E. & Field, J. K. Lung cancer LDCT screening and mortality reduction - Evidence, pitfalls and future perspectives. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18, 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-00432-6 (2021).

Choo, J. Y. et al. Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of small (= 1 cm) lung nodules under C-arm cone-beam CT virtual navigation guidance</at. Eur. Radiol. 23, 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2644-6 (2013).

Gould, M. K. et al. Evaluation of patients with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 132, 108S-130S (2007). https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.07-1353

Murphy, M. C., Wrobel, M. M., Fisher, D. A., Cahalane, A. M. & Fintelmann, F. J. Update on image-guided thermal lung ablation: Society guidelines, therapeutic alternatives, and postablation imaging findings. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1–15. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.21.27099 (2022).

Rossi, S. et al. Percutaneous computed tomography-guided radiofrequency thermal ablation of small unresectable lung tumours. Eur. Respir J. 27, 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00052905 (2006).

Wiener, R. S., Schwartz, L. M., Woloshin, S. & Welch, H. G. Population-based risk for complications after transthoracic needle lung biopsy of a pulmonary nodule: an analysis of discharge records. Ann. Intern. Med. 155, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00003 (2011).

Tipaldi, M. A. et al. Diagnostic yield of CT-guided lung biopsies: How can we limit negative sampling? Br. J. Radiol. 95 https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20210434 (2022).

Jin, K. N. et al. Initial experience of percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of lung nodules using C-arm cone-beam CT systems. Eur. Radiol. 20, 2108–2115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-010-1783-x (2010).

Ohno, Y. et al. CT-guided transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy of small (< or = 20 mm) solitary pulmonary nodules. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 180, 1665–1669. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801665 (2003).

Arias, S. et al. Use of electromagnetic navigational transthoracic needle aspiration (E-TTNA) for sampling of lung nodules. J. Vis. Exp. e52723 https://doi.org/10.3791/52723 (2015).

Yarmus, L. B. et al. Electromagnetic navigation transthoracic needle aspiration for the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules: A safety and feasibility pilot study. J. Thorac. Dis. 8, 186–194. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.47 (2016).

Lee, J. H., Hwang, E. J., Kim, H. & Park, C. M. A narrative review of deep learning applications in lung cancer research: From screening to prognostication. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 11, 1217–1229. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr-21-1012 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. A deep learning model integrating mammography and clinical factors facilitates the malignancy prediction of BI-RADS 4 microcalcifications in breast cancer screening. Eur. Radiol. 31, 5902–5912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-020-07659-y (2021).

Xu, J. et al. Deep Network for the automatic segmentation and quantification of intracranial hemorrhage on CT. Front. Neurosci. 14, 541817. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.541817 (2020).

Lin, D. J., Johnson, P. M., Knoll, F. & Lui, Y. W. Artificial intelligence for MR image reconstruction: An overview for clinicians. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 53, 1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.27078 (2021).

Egger, J. et al. Medical deep learning-A systematic meta-review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 221, 106874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2022.106874 (2022).

Neves, C. A., Tran, E. D., Blevins, N. H. & Hwang, P. H. Deep learning automated segmentation of middle skull-base structures for enhanced navigation. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 11, 1694–1697. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22856 (2021).

Chen, X. et al. A fully automated noncontrast CT 3-D reconstruction algorithm enabled accurate anatomical demonstration for lung segmentectomy. Thorac. Cancer. 13, 795–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.14322 (2022).

Song, J. W. et al. Electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy-guided dye marking for localization of pulmonary nodules. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 113, 1663–1669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2021.05.004 (2022).

Zhang, B. et al. A novel technique for preoperative localization of pulmonary nodules using a mixture of tissue adhesive and iohexol under computed tomography guidance: A 140 patient single-center study. Thorac. Cancer. 12, 854–863. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13826 (2021).

Zhao, G. et al. Factors affecting the accuracy and safety of computed tomography-guided biopsy of intrapulmonary solitary nodules =30 mm in a retrospective study of 155 patients. Exp. Ther. Med. 13, 1986–1992. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.4179 (2017).

Huang, M. D. et al. Accuracy and complications of CT-guided pulmonary core biopsy in small nodules: A single-center experience. Cancer Imaging. 19 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40644-019-0240-6 (2019).

Liu, H. et al. Efficacy and safety analysis of multislice spiral CT-guided transthoracic lung biopsy in the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules of different sizes. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 8192832 (2022).

Heerink, W. J. et al. Complication rates of CT-guided transthoracic lung biopsy: Meta-analysis. Eur. Radiol. 27, 138–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-016-4357-8 (2017).

Fior, D. et al. Virtual guidance of percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy with C-arm cone-beam CT: Diagnostic accuracy, risk factors and effective radiation dose. Cardiovasc. Intervent Radiol. 42, 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-019-02163-3 (2019).

Faiella, E. et al. Percutaneous low-dose CT-guided lung biopsy with an augmented reality navigation system: Validation of the technique on 496 suspected lesions. Clin. Imaging. 49, 101–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.11.013 (2018).

Wood, B. J. et al. Navigation with electromagnetic tracking for interventional radiology procedures: A feasibility study. J. Vasc Interv Radiol. 16, 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.RVI.0000148827.62296.B4 (2005).

Khan, M. F. et al. Navigation-based needle puncture of a cadaver using a hybrid tracking navigational system. Invest. Radiol. 41, 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.rli.0000236910.75905.cc (2006).

Zhang, Y. et al. Clinical value of an electromagnetic navigation system for CT-guided percutaneous lung biopsy of peripheral lung lesions. J. Thorac. Dis. 13, 4885–4893. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-21-395 (2021).

Moncharmont, L., Moreau-Gaudry, A., Medici, M. & Bricault, I. Phantom evaluation of a navigation system for out-of-plane CT-guided puncture. Diagn. Intervent. Imaging. 96, 531–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2015.03.002 (2015).

Appelbaum, L., Sosna, J., Nissenbaum, Y., Benshtein, A. & Goldberg, S. N. Electromagnetic navigation system for CT-guided biopsy of small lesions. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 196, 1194–1200. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.10.5151 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged Jie Chen, Weidao Chen, Shuang Wu, Yongfeng Mai, Yi Yang for technical support. We appreciate Dr. Shiyu Chen’s help in the illustrations in this manuscript. Infervision Medical Technology Co., Ltd. provided the electromagnetic navigation system. This study is supported by the Hunan Provincial Key Area R&D Program (2023SK2034) and Health Special Fund Research Project of Hunan province (B2021-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P., X.F., and X.C. wrote the main manuscript text. M.P., X.C, Q.H., X.M., B.W., Z.W., H.H., L.T., X.H., Y.Y. participated in phantom and animal experiments. C.Q., H.Z., Q.L., F.Y developed the system used in the experiment. M.P., X.F. C.Q., and H.Z prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

Animal experiment complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and commenced with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of The Second Xiangya Hospital (No. 2021842).

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT 3.5 in order to correct the English grammar of the first draft. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, M., Fan, X., Hu, Q. et al. Deep-learning based electromagnetic navigation system for transthoracic percutaneous puncture of small pulmonary nodules. Sci Rep 15, 2547 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85209-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85209-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A novel intravascular navigational ultrasound system for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt procedures

CVIR Endovascular (2025)

-

DA3-LUNGNET: a multi-stage deep framework with adaptive attention for early detection of subcentimeter pulmonary nodules

Health Information Science and Systems (2025)