Abstract

Fatigue can cause human error, which is the main cause of accidents. In this study, the dynamic fatigue recognition of unmanned electric locomotive operators under high-altitude, cold and low oxygen conditions was studied by combining physiological signals and multi-index information. The characteristic data from the physiological signals (ECG, EMG and EM) of 15 driverless electric locomotive operators were tracked and tested continuously in the field for 2 h, and a dynamic fatigue state evaluation model based on a first-order hidden Markov (HMM) dynamic Bayesian network was established. The model combines contextual information (sleep quality, working environment and circadian rhythm) and physiological signals (ECG, EMG and EM) to estimate the fatigue state of plateau mine operators. The simulation results of the dynamic fatigue recognition model and subjective synchronous fatigue reports were compared with the field-measured signal data. The verification results show that the synchronous subjective fatigue and simulated fatigue estimation results are highly consistent (correlation coefficient r = 0.971**), which confirms that the model is reliable for long-term dynamic fatigue evaluation. The results show that the established fatigue evaluation model is effective and provides a new model and concept for dynamic fatigue state estimation for remote mine operators in plateau deep mining. Moreover, this study provides a reference for clinical medical research and human fatigue identification under high-altitude, cold and low-oxygen conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mineral resources are the pillar of the national economy in China and play a key role in sustainable development. The mining industry is recognized as a high-risk industry, with multiple accidents annually. According to statistics, from 2001 to 2016, a total of 21,053 noncoal mine accidents occurred in China, resulting in 25,214 deaths1. From 1950 to 2018, a total of 188 major coal mine accidents occurred, resulting in 11,526 deaths2. Studies have shown that unsafe human behavior accounts for 97.67% of the direct causes of fatal coal mine accidents in China3.

Obviously, human error is an important factor that can cause accidents. Working in underground mines, poor working conditions and natural environmental conditions have enormous impacts on people’s cognition, perception, physiology and psychology3. These factors easily cause workers to experience physiological, psychological and physical fatigue and can result in human error. Thus, fatigue is a major cause of human error. Over time, the technical, physiological and psychological requirements of mine operators have increased, and many tasks involving human‒machine interactions are particularly prominent. When the brain must concentrate on controlling precision mining equipment for a long time, the brain load can be intense, and operator fatigue easily occurs, which reduces the attention span, judgment ability and coordination ability of remote operators; affects the performance and accuracy of operator control; and thus can lead to serious accidents4. In particular, under high-altitude, cold and low-oxygen working conditions, operators can experience high physiological and psychological pressures, and the probability of remote operator fatigue is high in plateau environments5,6. Therefore, to effectively prevent and reduce the risk of safety accidents caused by human errors, it is necessary to study the physiological characteristics of fatigue and establish dynamic fatigue recognition models for miners working in extreme environments involving deep mining on plateaus.

In recent years, many scholars have predicted and evaluated driver fatigue based on physiological and psychological signal characteristics, such as electrocardiogram (ECG), electromyography (EMG), electro-ophthalmogram (EOG) and electroencephalogram (EEG)7,8,9 signals. Driver fatigue recognition models include linear discriminant recognition, decision tree, logistic regression, random forest, neural network (NN), convolutional neural network recognition, support vector machine, Bayesian network and dynamic Bayesian network models10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30.

Among the above methods, dynamic Bayesian networks (DBNs) are the most promising for future work because they explicitly simulate the continuous development of driver fatigue over time and incorporate contextual information, such as environmental factors that affect tired driving; moreover, the DBN graph structure can be used to simulate the interrelationships among potential problems. The dynamic components of the model specify dependencies across time31. For example, a sleepy driver may stay sleepy, while an awake driver tends to stay awake. The specification of a DBN must include information regarding the probability or probability distribution of each relationship in the representation model32. However, to our knowledge, very few studies have investigated fatigue evaluation for miners living at high altitudes and in cold areas. This research team combined the above research techniques to carry out field test analyses and fatigue classification recognition model research for the first time in China. This work fills a gap in the mining research field.

This paper is based on physiological fatigue, psychological fatigue, physical fatigue, information fusion and machine learning theory. The ECG, EMG and eye movement (EM) signals of operators in plateau deep mining areas were measured continuously for 120 min. Feature fusion and an optimization analysis of field test data are carried out based on gray relational degree analysis. A dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model based on contextual information and ECG, EMG and EM signals was constructed, the performance of the model was verified via subjective–objective fatigue comparison, and the dynamic trends of remote operator fatigue in high-altitude, low-temperature and low-oxygen environments were summarized. The purpose of this study was to provide support for dynamic fatigue detection and recognition for miners and to provide a reference for clinical research and studies of the altitude acclimation ability of plateau workers in high-altitude, low-temperature and hypoxic environments.

The structure of this study is organized as follows. Section “Experiments and data analysis methods” introduces the test site environment, data acquisition and processing steps, and data signal fusion analysis method. Section “DBN-based fatigue recognition model” describes in detail the process of establishing a dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model. The results of the field test data analysis and fatigue model recognition performance analysis are given in detail in Sect. “Data analysis and results”. In Sect. “Discussion”, the results are analyzed and discussed, and the findings are compared with those of previous scholars. Moreover, the limitations and shortcomings of this study are noted. Part 6 summarizes the main results of this study.

Experiments and data analysis methods

Subject details

Fifteen male driverless electric locomotive operators (referred to as operators) from the Pulang Copper Mine in China were randomly selected as the research objects, and the data were extracted through long-term (2 h) field measurements. The average age of the subjects was 27.3 ± 5.7 years, the average height was 165.2 ± 7.8 cm, and the mean weight was 62.7 ± 8.7 kg. The subjects had no history of cardiovascular disease and were in good health. There was no alcohol consumption for 24 h, and no caffeinated beverages were consumed for 12 h prior to the trial. Before the experiment, the participants got more than 8 h of continuous sleep. All the subjects were familiar with the experimental procedure and signed informed consent forms.

Experimental environment

In this study, the fatigue characteristics of driverless electric locomotive operators were measured in the field, and a fatigue recognition model was applied. The environmental conditions were as follows: altitude 3200 ~ 4000 m, atmospheric pressure 67.9 ~ 62.4 kPa, temperature -5 ~ -20 ℃, and oxygen level 19 ~ 20%.

Experimental apparatus

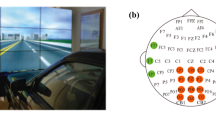

The MP160 physiological recording and analysis system developed by the American company BIOPAC was used for simultaneous acquisition, preliminary processing and analysis of ECG and EMG signals. The equipment is mainly used for the collection of physiological signals, such as EEG, ECG and EMG signals. The transmission mode is a 2.4 GHz two-way digital RF transmitter with a sampling rate of 2000 Hz. The ECG signal was obtained with a chest connection method and preprocessed, and the ECG index was extracted through filter denoising, wavelet change detection and a slip window. Moreover, we used the analysis software Tobii Glasses 2 produced in Sweden to conduct a synchronous tracking test and analyze the relevant data regarding operator eye movements. The relevant experimental equipment and field test setup are shown in Fig. 1.

Experimental process

The subjects were allowed to rest for 10 min before the test. Then, an Ag/AgCl electrode was placed on the subjects as required and connected to the MP160 analysis system via a wire. An eye movement test instrument was worn for synchronous data acquisition. The results were stored in a computer for further processing, and the subjects spoke as little as possible throughout the trial. The specific test process and precautions were as follows.

-

(1) To accurately assess the physiological rhythm changes associated with operator fatigue at altitude, the experimental phase of this study included physiological rhythm changes from 14:00 to 16:00, a high-incidence period of operator fatigue, for a total of more than 2 h of synchronous testing.

-

(2) First, the participants were asked to explain the experimental tasks to ensure that they correctly understood the experimental steps and significance. Then, the formal experiment began. Before the experiment, personal information such as height and weight was recorded, and a subjective fatigue scale was used. The subjective fatigue questionnaire was based on the results of fatigue research by Japanese scholar Masatsu Oshima33. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire have been verified. At the same time, seven-point Likert scale has been widely used in market research, social science, psychology, education and other fields, and its reliability and validity have been verified and recognized. Therefore, this paper chooses the questionnaire and scale. There were 24 items in the questionnaire, and the fatigue scale was a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”, which was applicable to all the variables. In the experiment, data were synchronously recorded for 2 h, and a subjective fatigue score was given every 10 min. The real-time monitoring data were divided into 13 portions (the data from period 0 were the reference data from a pretest). Thus, according to the operator’s feelings, this approach was used to determine whether a state of controlled fatigue was achieved, and subjective and objective fatigue results were compared.

-

(3) The ECG signal was acquired by surface electrodes attached to collect ECG signals, positive electrodes attached to the fourth intercostal space of the left margin of the sternum, negative electrodes attached to the fourth intercostal space of the right margin of the sternum, and reference electrodes attached to the lower margin of the clavicle. After preparing the ECG leads, the formal experiment started, and the heart rate variability signals were obtained following signal preprocessing, such as denoising, filtering, sliding windowing application and R-wave detection34. The EMG module uses a differential input, with the corresponding measurement electrode placed on the brachioradialis of the forearm. The real-time test setup is shown in Fig. 2.

-

(4) Tobii Glasses 2 analysis software was used to conduct a synchronous tracking test and obtain relevant data regarding each operator’s eye movements. The real-time test setup is shown in Fig. 2.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Northeastern University (23–2019-0105). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects following a detailed explanation of the study objectives and protocol to each subject. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to being monitored.

Feature fusion and optimization

In this study, ECG, EMG and EM data were used as the main observations input into the dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model, and the corresponding observation indices were LF/HF, mean F and pupil diameter, respectively. Gray correlation analysis was used to carry out feature optimization for these features (the gray correlation analysis is explained in reference35).

DBN-based fatigue recognition model

Dynamic Bayesian estimation

The traditional static Bayesian network model often has limitations when analyzing the characteristics of complex systems, such as multistage changes and event correlations, while a dynamic Bayesian network can describe the system state space, failure correlations and dynamic evolution process based on the form of the local state and conditional probability. Bayesian networks fuse information in the temporal dimension to form probability-based mathematical models with bidirectional information reasoning ability36. The “dynamic” nature of dynamic Bayesian networks does not mean that the model framework changes with time. Generally, topological dynamic Bayesian networks are static over time. However, the conditional probability at each node, based on the observed value and inference algorithm, changes with time. In this paper, according to the fatigue characteristics of personnel, based on a 3-layer first-order hidden Markov model (see Fig. 3), the transfer probability between fatigue states at the previous time slice is considered, and the information is transferred to the next time slice in turn. Specifically, we use a graphical model (Fig. 3) for fatigue state assessment to illustrate our fatigue detection approach. The joint distribution of the first-order HMM can be expressed as36,37

where C is the context variable and Y is the fatigue potential variable. O is the observed variable. The establishment of the dynamic Bayesian recognition model is described in detail in Sect. “Establishment of the dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model”.

According to the dynamic Bayesian structural model based on the first-order HMM (as shown in Fig. 3), the Bayesian measurement model, as shown in Fig. 4, is established in combination with the actual operations performed by miners at high-altitude mines. However, in this study, the structural model used is a typical three-layer hidden Markov model composed of contextual information, hidden variables (fatigue states) and observed variables. This structural model is used to estimate the fatigue probability of the operator. The fatigue recognition structure model combines the current context information, the observed value information (observed variable evidence) and the fatigue state information from the previous time slice to dynamically evaluate the current fatigue state of the operator.

Main nodes of the dynamic Bayes network

In this study, ECG, EMG and EM signals were selected as the observed variables of the dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model. According to the above description and analysis of the dynamic Bayes principle, this study preliminarily summarizes the main nodes that affect fatigue according to the characteristics of plateau miners operating unmanned equipment (as shown in Fig. 5), and the relevant nodes are introduced in detail in the following section.

Circadian rhythm (CR) analysis

Lal et al.38 noted that CR is an important factor to consider in the study of operator fatigue. They found that sleep intention is strongest at 3:00–5:00 AM and 15:00–17:00 PM every day; that is, fatigue may reach the highest level at these times. Moreover, CR is the main factor affecting operator alertness39. Therefore, this study chooses CR as the context variable corresponding to the DBN nodes. Moreover, CR analysis is highly depended on the time interval selected.

Work environment (WE) analysis

Obviously, the indoor working environment has an important impact on remote operator fatigue. Notably, noise and temperature are important factors in the working environment. Therefore, these factors are treated as two contextual features corresponding to DBN nodes.

Sleep quality (SQ) analysis

Sleep quality is an important contextual characteristic that affects the degree of fatigue and is directly related to fatigue40. The sleep quality of an operator is related to several factors, such as the sleep environment, duration and conditions. Among these factors, the effects of light, noise and temperature on sleep quality are dominant13.

ECG analysis

ECG signal analysis, which includes time-domain analysis and frequency-domain analysis, is considered the gold standard for evaluating fatigue. In general, frequency-domain analysis is most popular, mainly including low-frequency (LF), ultralow-frequency, high-frequency (HF) and ultrahigh-frequency features. Among these frequency features, the LF/HF ratio displays a strong relationship with operator fatigue. Chen et al.41 noted that the LF/HF ratio gradually and significantly increases during the transition from wakefulness to fatigue. Therefore, the LF/HF of the operator fatigue state is selected as the observable variable at the DBN nodes in this study.

Eye movement (EM) analysis

Pupil diameter and eye fixation, blinking and closure durations are different manifestations of EM42. When an operator is fatigued, their pupil diameter significantly changes43; thus, pupil diameter is a reliable and effective metric for assessing operator fatigue27 and is selected as the observable variable corresponding to the DBN nodes in this study.

EMG analysis

EMG signals reflect the electrical activity on the skin surface during muscle contraction. In recent years, noninvasive EMG has been widely used in muscle fatigue analysis. In this study, the EMG signal was measured, the time–frequency characteristics were analyzed, and the median frequency (median F) was selected as the observable variable corresponding to the nodes of the DBN graph.

Establishment of the dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model

Wylie et al.44 noted that fatigue is cumulative over time. The fatigue state at the previous moment affects the current fatigue state. Therefore, to effectively monitor human fatigue, it is necessary to establish a dynamic fatigue recognition model28. A DBN can be used to represent continuous and discrete random processes, and time nodes are introduced into the static BN structure to represent the time-dependent dynamics of modeled processes29 (see Fig. 6). In this study, only discrete random processes are considered (see Fig. 7). That is, context variables, hidden variables, and observed variables are used in a discrete DBN, and a fatigue recognition model based on a discrete DBN is constructed (Fig. 7). The first step is to specify the nodes of the discrete DBN are determined. The second step is to determine the value of each discrete variable. The third step is to configure the initial state of the variable (calculate the SBN at t = 1). The last step is to establish a dynamic Bayesian network (DBN)45. These steps are described in detail below.

Step 1: Determining the nodes of the discrete Bayesian network

According to the working characteristics of the operators, the main nodes of the fatigue model are determined in this paper, as shown in Fig. 5. The Bayesian structure is established based on the 3-layer HMM principle of contextual, latent and observation variables (see Fig. 5). Each identified discrete node is described in Sect. “Main nodes of the dynamic Bayes network”.

Step 2: Specifying discrete values for each node

Figure 6 summarizes each variable of the Bayesian model and the corresponding state values. \(Y = [Y_{t}^{1} ,Y_{t}^{2} ]\) represents the fatigued and nonfatigue states, respectively. The contextual feature nodes \(C = [C_{t}^{1} ,C_{t}^{2} ,C_{t}^{3} ]\) represent CR, SQ and WE, respectively. However, the observation feature nodes \(O = [O_{t}^{1} ,O_{t}^{2} ,O_{t}^{3} ]\) represent the ECG, EM and EMG signals, encompassing contact and contactless physiological features.

In particular, in Fig. 6, \(y_{t}^{k}\), \(c_{t}^{i,m}\), and \(o_{t}^{j,n}\)(\(k, \, m = 1,{ 2; }i = 1, \, 2, \cdots 10; \, j, \, n = 1,{ 2, 3}\)) denote the specific values of \(Y = [Y_{t}^{1} ,Y_{t}^{2} ]\), \(C = [C_{t}^{1} ,C_{t}^{2} ,C_{t}^{3} ,C_{t}^{4} ,C_{t}^{5} ,C_{t}^{6} ,C_{t}^{7} ,C_{t}^{8} ,C_{t}^{9} ,C_{t}^{10} ]\), and \(O = [O_{t}^{1} ,O_{t}^{2} ,O_{t}^{3} ]\), respectively. As shown in Fig. 6, \(P(c_{t}^{i,j} )\) represents the probability of CR node states, SQ node states and WE node states being observed, such as {\(c_{t}^{1,1} = drowsy\),\(c_{t}^{1,2} = active\)}, {\(c_{t}^{2,1} = bad\), \(c_{t}^{2,2} = good\)}, and {\(c_{t}^{3,1} = bad\),\(c_{t}^{3,2} = good\)}. \(P(o_{t}^{i,j} )\) represents the probability set for the contact physiological node states (ECG and EMG nodes) and contactless physiological node states (EM nodes).

Step 3: Calculations with a static Bayesian network (SBN)

We can define the static Bayes algorithm at the moment fragment of \(t = 1\), as shown in Fig. 6. It is assumed that the evidence at time slice \(t = 1\) is represented as \(e_{1}^{c} = \{ e_{c,1}^{i,j} \}\) at a contextual node. Here, \(e_{c,1}^{i,j}\) represents the evidence at the \(i\) th contextual node with the \(j\) th state value, and \(e_{1}^{o} = \{ e_{o,1}^{i,j} \}\) it the set of observable nodes, where \(e_{o,1}^{i,j}\) represents the evidence at the \(i\) th observable node with the \(j\) th state value. \(e_{1} = \{ e_{1}^{c} ,e_{1}^{o} \}\) denotes the evidence from the contextual factors and observable feature nodes at time \(t = 1\). Then, the conditional probability at \(Y\) given the occurrence of \(e_{1}^{c}\) can be expressed as29,46,47

and the conditional probability of \(e_{1}^{o}\) given the information at node \(Y\) can be written as29,46,47

where \(k = 1, \, 2{\text{ and }}j = 1, \, 2, \, 3.\) However, according to Bayes’ theorem, the conditional probability at node \(Y\) (given the occurrence of \(e_{1}\) at time \(t = 1\)) can be obtained by combining Eqns. (2) and (3) as follows:

where \(\sum\limits_{j = 1}^{2} {P(Y = y_{1}^{j} \left| {e_{1}^{c} } \right.)P(e_{1}^{o} \left| {Y = y_{1}^{j} } \right.)}\) is the marginal probability, which is the prior probability based on all possible hypotheses for fatigue Y. Thus, Eqs. (2)-(4) are representative of the initial case, i.e., the SBN at time \(t = 1\).

Step 4: Calculations with dynamic Bayesian networks (DBNs)

In this paper, according to the working conditions for a driverless operator (as shown in Fig. 2), combined with the context and observation variables affecting fatigue, we construct a DBN structure for fatigue measurement at time \(t\) (shown in Fig. 7). However, a DBN can be seen as an SBN with interconnected time slices and that shifts over time. Based on a first-order hidden Markov model, the relationship between the adjacent time slice \(t{ - }1\) and t can be established via a dynamic interaction model. The correspondence between \(t{ - }1\) and t is shown in Fig. 7. The random fatigue variable at the current time slice t is affected by the context variable and the observable variable at the current time slice \(t\). At the same time, the random fatigue variable is affected by information from the previous time point \(t{ - }1\).

where \(P(y_{t - 1}^{m} )\), m = 1, 2 denotes the conditional probability at node Y for time slice \(t{ - }1\) (with different state values). The conditional probability at \(Y\) given that the occurrence of \(e_{t}^{c}\) at time slice \(t\) can be obtained using Eq. (2). The conditional probability of \(e_{t}^{o}\) at time slice \(t\) given the information at node \(Y\) can be calculated using Eq. (3).

However, given the occurrence information for \(Y\) at time t, the conditional probability of \(e_{t} = \{ e_{t}^{c} ,e_{t}^{o} \}\) is obtained by combining Eqns. (5) and (6), as shown in Eq. (7).

Equations (5)-(7) can be used to obtain the conditional fatigue probability over time slice t.

Data analysis and results

In this section, the dynamic fatigue state response of operators in high-altitude mining areas is introduced. Physiological indicators (EM, ECG and EMG) tested for a long period (120 min) in the field were used as evidence in the dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model, and the probabilities at each parent node and child node in the dynamic Bayesian fatigue recognition model were calculated. The variation in the operator fatigue state over time was obtained by combining the results. Likewise, the results of the fatigue recognition model were verified with a questionnaire survey and subjective and objective comparisons of the physiological characteristics of the subjects.

Dynamic subjective evaluation of the fatigue degree

(1) Results of the subjective evaluation of dynamic fatigue severity throughout the day.

In this study, the subjective evaluations of fatigue throughout the whole day by 59 miners were investigated via a field questionnaire. The results of the investigation are shown in Fig. 8. The survey results show that the peak fatigue for miners throughout the day is mainly concentrated from 1:00–3:00 P.M. and 3:00–5:00 A.M.

(2) Dynamic subjective evaluation results of the 2-h field tracking and testing of fatigue degrees in this study, 15 operators were tracked and tested (among them, 5 subjects were excluded because they did not complete the whole test or because some data were missing, leaving 10 valid subjects). The follow-up test time was longer than 2 h, and the fatigue questionnaire was subjectively administered every 10 min during real-time monitoring. The results obtained through a mathematical analysis of the questionnaire results and the normalization of fatigue severity degrees are shown in Fig. 9. The results of the investigation and analysis showed that the peak 2-h fatigue probability was mainly concentrated between 70 and 100 min. The fatigue degree increased linearly before 90 min of work, plateaued slightly after 100 min, and then increased after a certain period of time.

Calculation results and analysis of the correlation probability of the fatigue state evaluation model based on the dynamic Bayes method

After the dynamic Bayesian structure model was established (as shown in Fig. 10), the next key process was to determine the prior probability of the parent nodes and the conditional probabilities of the connected child nodes. GeNIe 2.3 software was used for modeling, and the specific modeling results are shown in Fig. 10. In general, these probabilities were obtained by a statistical analysis of large amounts of training data. This study references probabilistic information from several confirmed published papers13,27,28,29,40,45,48,49,50,51,52,53. Through Bayesian network calculations and analysis, the following prior probability and conditional probability values used in the DBN model were obtained.

(1) The prior probability of the outermost node causing fatigue

As shown in Fig. 10, the outermost nodes of the dynamic Bayesian fatigue structure model include those associated with light, random noise, heat, working environment noise, ambient temperature and working period. The prior probabilities for the outermost nodes obtained from the literature13,28,29 are shown in Table 1.

(2) Intermediate node probability calculation results

An intermediate node could be a parent node, a child node, or a dual parent–child node, as shown in Fig. 10. The sleep environment encompasses the light, random noise, heat and sleep quality child nodes. However, the corresponding probability for the sleeping environment based on the original probability is also a prior probability in other cases. Therefore, the probability of each intermediate node can be calculated with the total probability formula based on the prior probability and conditional probability of the parent node. The probability calculation results for each intermediate node are shown in the table below.

Sleep environment probability calculation results

The conditional probabilities of the parent nodes related to the sleeping environment are given in Table 2. According to the prior and conditional probabilities given in Table 1 and Table 2, the original probability (prior probability) of a sleep environment node can be calculated with the total probability formula and GeNIe software, as shown in Fig. 11. The calculation results are as follows: P(sleep environment = poor) = 0.2302, and P (sleep environment = normal) = 0.7698.

Calculation results for sleep quality probability

Table 3 shows the conditional probabilities for the parent nodes of sleep quality. According to the prior and conditional probabilities given in Table 1 and Table 3, as well as the calculated prior probability of the sleep environment, the original probability (prior probability) for a sleep quality node can be calculated based on the total probability formula and GeNIe software, as shown in Fig. 12. The calculation results are as follows: P(SQ = bad) = 0.1168, and P(SQ = good) = 0.8832.

Circadian rhythm probability calculation results

The conditional probabilities for the parent nodes of the circadian rhythm are given in Table 4. Moreover, according to the prior probabilities in Table 1, the original probabilities (prior probabilities) of the circadian rhythm nodes can be calculated based on the total probability formula and GeNie software, as shown in Fig. 13. The calculation results are P (CR = drowsy) = 0.1930 and P(CR = active) = 0.8070.

Calculation results for working environment probability

Table 5 shows the conditional probabilities of parent nodes in the working environment. Moreover, according to the prior probabilities in Table 1, the original probabilities (prior probabilities) of the working environment nodes can be calculated based on the total probability formula and GeNIe software, as shown in Fig. 14. The calculation results are P(WE = bad) = 0.2885 and P(WE = good) = 0.7115.

Calculation of fatigue probability results

The conditional probabilities of fatigue-related parent nodes are given in Table 6. Moreover, the prior probabilities associated with the context information (CR, SQ, and WE) obtained above are shown in Fig. 15. The original probabilities of the fatigue nodes can be calculated based on the total probability formula and GeNIe software, and the calculation results are P(fatigue = fatigue) = 0.2205 and P(fatigue = no fatigue) = 0.7795.

According to the prior and conditional probabilities calculated above, the original probabilities of the intermediate nodes in the Bayesian structure model can be calculated, and each probability result is shown in Table 7.

Dynamic estimation results and analysis of the fatigue evaluation model based on the dynamic Bayes method

(1) Fatigue dynamic node conditional probability and transition probability results.

According to the operating conditions, operator fatigue level, and contextual and observed variables that affect fatigue, the DBN for fatigue measurement at time t was established, as shown in Fig. 7. However, the DBN can be seen as an interconnected time slice of the SBN that changes over time and used to construct a dynamic Bayesian fatigue assessment model. That is, based on a first-order hidden Markov model, a dynamic interaction model between the adjacent time slices \(t{ - }1\) and \(t\) can be established. The corresponding relationship between \(t{ - }1\) and \(t\) is shown in Fig. 7. The random fatigue variable at the current time slice \(t\) is affected by the contextual information variable and the observation variable at the current time slice. It is also affected by the random fatigue variable at the previous time point \(t{ - }1\). The mathematical expression of the dynamic Bayesian model is as follows:

where \(P(y_{t - 1}^{m} )\) (m = 1 and 2) represents the conditional probability at node Y (fatigue) at time slice \(t{ - }1\) (with different state values). \(Y = [Y_{t}^{1} ,Y_{t}^{2} ]\) indicates fatigue or no fatigue. \(C = [C_{t}^{1} ,C_{t}^{2} ,C_{t}^{3} ]\) reflects the status values of the CR, SQ and WE context information nodes.

(1) According to the calculations in the previous section, the posterior probabilities of fatigue and nonfatigue at the initial time (denoted as \(t{ - }1\)) are P(fatigue = fatigue) = 0.2205 and P(fatigue = no fatigue) = 0.7795, respectively. Moreover, the conditional probability that the observed variable given in reference29 is associated with a fatigue node is shown in Table 8, and the probability for each node in the model is obtained. According to the original and conditional probabilities for each node, the original probability values in the fatigue recognition model can be obtained. It is assumed that the fatigue state at time \(t\) is affected not only by the contextual information in the current period but also by the state at the previous time step (\(t{ - }1\)). That is, the transition probability of fatigue at time \(t\) is expressed as shown in Fig. 1613. Figure 16 summarizes the fatigue transfer probability at a fatigue node from the previous time step \(t{ - }1\) to the next time t and the conditional probability of the connection of the fatigue node at time \(t\).

(2) The dynamic observed variables at fatigue nodes and the probability calculation results with the corresponding evidence

Fatigue is a hidden variable, and the fatigue degree is affected by contextual information; moreover, fatigue is a relatively cumulative process over time. Thus, there are limitations when predicting fatigue based solely on contextual information. In this study, a comprehensive fatigue evaluation model is established by comprehensively considering contextual information and the characteristics (observed variables) of fatigue, thus overcoming the need for an evaluation model that considers only the impact of contextual information on fatigue. However, the degree of fatigue is expressed through numerous physical and psychological characteristics. In this study, several gold-standard indicators of fatigue characterization (ECG-, EMG-, and EM-based indicators) were selected as the observational variables related to fatigue probability. Generally, the prediction of fatigue probability based on fatigue observation variables is based on the construction of a prediction model with temporal changes by using past and present observations similar to the predicted event in a time series; in this approach, the prediction trend for a future event is obtained considering certain rules. The probability of the observed variables in the prediction model being used as predictive evidence is a key factor in dynamic Bayesian network prediction. Next, the observational evidence and calculation of fatigue are described in detail.

The specific observed ECG, EMG and EM signals are fuzzy and quantified within given ranges. The quantified results are used as the inputs of the dynamic Bayesian fatigue assessment model. For example, the value of EM is EM = (small, medium, large), and a triangular membership function is used for the fuzzy subset of eye movement, as shown in Fig. 17, where the \(x\)-axis gives the pupil diameter as an eye movement index.

However, the EM membership functions are as follows54:

For different variables and application scopes, parameters \(a_{1}\), \(a_{2}\), \(a_{3}\) and \(b\) in the formula should be selected with different values.

In the field test in this study, 10 subjects were fully tracked and tested in real time over 2 h. The collected data were divided into 12 segments (every 10 min was considered an observation time segment), and a total of 13 time segments were considered, including 1 before the start of the experiment. The results were obtained based on statistics and are shown in Table 9. Through analysis and selection, \(a_{1}\) = 1.2, \(a_{2}\) = 1.5, \(a_{3}\) = 1.8, and \(b\) = 0.3 were selected for the ECG observation variables. For the EMG observation variables, \(a_{1}\) = 40 ms2, \(a_{2}\) = 60 ms2, \(a_{3}\) = 80 ms2, and \(b\) = 20 ms2. For the EM observation variables, \(a_{1}\) = 3.5 mm, \(a_{2}\) = 3.75 mm, \(a_{3}\) = 4.00 mm, and \(b\) = 0.25 mm. The corresponding nodes were assumed to be independent of each other, and Table 9 gives the results and evidence for each observation node at different times.

(3) Dynamic recognition results and analysis of the dynamic Bayes fatigue assessment model

In this study, information fusion was used to identify fatigue while comprehensively considering contextual information and physiological indicators. The physiological indices of the operators were tracked and measured in the field. In the field work scenario, the fatigue recognition model was run by using test data. However, the evidence of observed variables obtained from the test (see Fig. 18) was input into the constructed fatigue recognition model, and the dynamic simulation fatigue assessment results obtained with GeNIe software are shown in Fig. 19. Specifically, Fig. 19 displays an analysis diagram of the dynamic simulation results of the fatigue state. As shown in Fig. 19, ① the fatigue of the subjects increased from 3 P.M. (P (fatigue) > 0.5) onward and displayed a sharp increasing trend. ② The total duration of sleepiness of the subjects spanned from approximately 3:10 P.M. to 3:40 P.M., which was consistent with the results of the field fatigue questionnaire (Fig. 20). ③ According to the overall fatigue assessment probability trend, operator fatigue continuously accumulates and increases. According to the results for test segments 5–13, the fatigue probability sharply increases and then stably decreases before increasing again. This result suggests that over time, when an operator reaches complete fatigue, the human body undergoes a certain adaptive process, and the degree of fatigue becomes relatively weakened; however, the operator is also in a state of fatigue. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 20, the variation trends and values of the subjective questionnaire survey results and the simulation results are generally consistent (correlation coefficient r = 0.971**), which confirms that the fatigue evaluation model established in this study yields good evaluation ability and effectiveness and provides a new model and concept for dynamic fatigue state estimation for miners in high-altitude and cold areas.

Discussion

Research has shown that under high-altitude and low-oxygen conditions, it is feasible to recognize fatigue in remote operators in mines by using ECG, EMG, and EM physiological indices and contextual information. Based on previous studies, a dynamic Bayesian network fatigue state evaluation model based on a first-order hidden Markov model (HMM) is established in this paper. This model combines contextual information and physiological signal characteristics to dynamically estimate the fatigue state of the operators of unmanned electric locomotives in plateau mining. Moreover, the verification of the model was carried out with actual mine field test data. The results showed that the model is reliable for long-term dynamic fatigue state evaluation. Clear operating procedures to guide operators to use equipment correctly and safely to reduce safety accidents caused by improper operation due to fatigue. Likewise, the probability of accidents is reduced by regularly checking whether the working condition of the operator is at its best. The practical results are obtained considering the dynamic changes in miners’ fatigue levels in extreme plateau environments, and the results verify the effectiveness of the model. The model can accurately predict the change of fatigue according to the physiological characteristics of the operators, and provide a basis for the formulation of mining safety operation rules and the matching of personnel’s working ability.

To our knowledge, there have been few studies of human fatigue in cold and high-altitude areas. Generally, field tests of remote operator fatigue under extreme working conditions remain in the exploratory phase. Therefore, this paper draws on some previous research results regarding driver fatigue and related topics. Table 10 summarizes the relevant studies and comparisons of human fatigue. Zhang et al.55 used an MP425 data acquisition card and LABVIEW acquisition system to collect ECG signals and extract ECG waveform features. A support vector machine was used to classify and identify visual fatigue. The results showed that the ECG signal characteristics changed significantly before and after the VDT fatigue test. The classification accuracy of the ECG single-feature model was more than 80%, and that of the model with combined features was 90%. Patel et al.56 proposed an early fatigue detection system for drivers based on artificial intelligence that adopted the HRV physiological index as a fatigue recognition index. The performance of the neural network fatigue recognition model was verified via laboratory tests. The accuracy of the neural network reached 90%, suggesting that fatigue detection based on HRV information is feasible. Awais et al.57 proposed a driver drowsiness detection method that combines ECG and EEG features and extracted various time-domain and frequency-domain features (HR, HRV, LF, HF and LF/HF) from ECG results. A support vector machine (SVM) classifier was used to evaluate the subjective sleepiness scale, and the accuracy of fatigue classification was 80.9%. Zhang et al.58 detected and identified driver fatigue from recorded ECG, EMG and EOG signals. The peak-to-peak values of entropy-based features, namely, wavelet entropy (WE), approximate entropy (PP-ApEn) and sample entropy (PP-SampEn), were extracted from the collected signals to estimate the driver fatigue state. An artificial neural network was tested and trained with the above features. The estimation accuracy was more than 96.5%. Research has shown that identifying worker fatigue through changes in ECG, EMG and EM physiological indices is feasible.

Several studies have explored the use of DBNs for detecting fatigue. Anthony et al.32 designed an algorithm for detecting driving drowsiness based on DBNs. In the algorithm, the steering wheel angle, pedal use patterns, speed and acceleration are used as inputs. Speed and acceleration are used to measure the driving environment in real time. This approach was verified with data collected from participants using a driving simulator. The findings verified that this algorithm is a promising new method for driver fatigue detection. Yuan et al.45 established a DBN model to measure 3D visual fatigue. A probabilistic framework based on the DBN structure was used to infer the visual fatigue state of 3D viewers. The results showed that as the number of features used in modeling increased, visual fatigue assessment results became more reliable and accurate, and dynamic features were highly important for assessing stereoscopic visual fatigue. Ji et al.27,28 developed an algorithm that combines contextual, face, eye, and head position inputs to predict sleepiness based on reaction time in nondriving alert tasks. Yang et al.29 extended the work by adding heart rate, EEG, and eye measurements as inputs to the previous algorithm. These studies demonstrated the potential effectiveness of DBN frameworks for detecting drowsiness.

Tian et al.59 Collected heart rate and blood oxygen values of drivers in National Highway 214 in Qinghai Province with Kangtai PM-60A car heart rate and blood oxygen meter to conduct driver fatigue test. The driving fatigue thresholds in the altitude range of 3000–3500, 3500–4000, 4000–4500 and 4500–5000 m are 2.86, 3.82, 4.54 and 10.2, respectively. The start time of driving fatigue are 35, 34, 32 and 25 min, respectively. The conclusion that fatigue accumulation is related to operation time is similar to this study. Sun et al.60 studied the fatigue development and change rules of apron controllers during each working process, and the research results showed that the heart rate characteristics were related to the workload of controllers and the change rules of personnel reaction time characteristics. The study can provide valuable reference for controller shift management and personnel status monitoring timing in daily work. This article makes the same point. Mietkiewicz et al.61 research results show that decision support systems (DSS) can improve the working efficiency of operators and reduce the cognitive workload. However, it also reveals trade-offs with situational awareness, which can be reduced when operators rely too heavily on the system’s guidance. David et al.62 proposed a method for analyzing assembly operation fatigue, which took into account the EAR (Eye Aspect Ratio) indicator, operator pose, and elapsed operating time to construct an identification model, and determined the fatigue level by processing multi-modal information obtained from various sources. The method adopted in our paper is similar to this study. Dai et al.63 used trends in eye blink rate, number of frames closed in a specified time (PERCLOS), and operator mouse speed to detect the degree of operator fatigue. At the same time, it is important to detect the fatigue state of operators accurately and quickly for the safety of production.

Fortunately, this study draws on the algorithms of previous scholars and the working characteristics of operators under high-altitude, cold and low oxygen conditions to construct a new DBN evaluation model of the dynamic fatigue state of miners. Through field tracking and testing of 2-h physiological signal (ECG, EMG and EM) data from unmanned electric locomotive operators at a mine site, the fatigue probability in each period was calculated for each time segment via the fuzzy method considering observed evidence. The dynamic fatigue recognition model was subsequently run, and the results were compared with the subjective synchronous fatigue levels based on field-measured data. The verification analysis showed that the synchronous subjective fatigue data strongly agreed with the simulated fatigue estimation results (correlation coefficient r = 0.971**), and the results of this study are highly similar to the results of other studies, further verifying that the model is reliable for long-term dynamic fatigue state evaluation. The fatigue evaluation model established in this study displays good evaluation ability and effectiveness and provides a new approach for the design of dynamic fatigue state estimation models.

This study inevitably has several limitations. Because the characteristics of the experimental instruments and the complexity of the mine site conditions have an impact on the experimental data, the sample size is relatively small. Second, when establishing the DBN model, the number of influencing factors considered is insufficient, and the prior probability at leaf nodes and the transition probability of the model need to be further verified. Third, because we are the first research team to carry out field tests of miner fatigue and perform miner fatigue identification in the extreme environment of a plateau in China, limited data are available for reference. Hence, in future research, we will try to increase the number of subjects, conduct multi-index tracking tests, and continue to further study the fatigue characteristics and fatigue recognition model of miners in high-altitude, cold areas.

Conclusion

In this study, the dynamic fatigue assessment of operators under high-altitude, cold and low-oxygen conditions was studied with physiological signals and multi-index information. A dynamic fatigue state evaluation model for miners based on a first-order hidden Markov model (HMM) and DBN was established. The model combines contextual information (SQ, WE and CR) and physiological signals (ECG, EMG and EM signals) to estimate the fatigue state of plateau mine operators. The physiological signal data were tracked and analyzed on site. The results of the dynamic fatigue recognition model and the subjective synchronous fatigue surveys were compared with field-measured data. The verification analysis showed that the synchronous subjective fatigue and simulation fatigue estimates strongly agreed with observed values (correlation coefficient r = 0.971**), which verified that the model is reliable for long-term dynamic fatigue state assessment. The fatigue evaluation model established in this study displayed good evaluation ability and effectiveness and provides a new approach for dynamic fatigue state estimation for remote operators in plateau deep mining.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Luo, Z., Shi, B. & Li, P. Analysis of the law of serious and extra serious accidents in non-coal mines in China during 2001–2016. Gold. 40(1), 67–70 (2019).

Zhang, J., Xu, K., Reniers, G. & You, G. Statistical analysis the characteristics of extraordinarily severe coal mine accidents (ESCMAs) in China from 1950 to 2018. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 133, 332–340 (2020).

Liu, J. & Song, X. Countermeasures of mine safety management based on behavior safety mode. Proced. Eng. 84, 144–150 (2014).

Xu, D. Discussion on the status and development of deep mining in metal mines. World Nonferrous Metals 22, 51–52 (2020).

León-Velarde, F. et al. Consensus statement on chronic and subacute high altitude diseases. High Alt. Med. Biol. 6, 147–157 (2005).

Wu, T. Chronic mountain sickness on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Chin. J. Pract. Intern. Med. 32, 321–323 (2012).

Kar, S., Bhagat, M. & Routray, A. EEG signal analysis for the assessment and quantification of driver’s fatigue. Transp. Res. F. 13(5), 297–306 (2010).

Öberg, T. Muscle fatigue and calibration of EMG measurements. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 5(4), 239–243 (1995).

Bhardwaj, R. & Balasubramanian, V. Viability of cardiac parameters measured unobtrusively using capacitive coupled electrocardiography (cECG) to estimate driver performance. IEEE Sens. J. 19, 4321–4330 (2019).

Khushaba, R. et al. Driver drowsiness classification using fuzzy wavelet-packet based feature extraction algorithm. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 58(1), 121–131 (2011).

Lin, C. et al. Adaptive EEG-based alertness estimation system by using ICA-based fuzzy neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I: Regul. Papers 53(11), 2469–2476 (2006).

Duann, J., Chen, P., et al. Detecting frontal EEG activities with forehead electrodes. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5638, 373-379 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, 2009).

Fu, R., Wang, H. & Zhao, W. Dynamic driver fatigue detection using hidden Markov model in real driving condition. Expert Syst. Appl. 63, 397–411 (2016).

Liu, W. et al. Research on medical data feature extraction and intelligent recognition technology based on convolutional neural network. IEEE Access 7, 150157–150167 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. Psychophysiological data-driven multi-feature information fusion and recognition of miner fatigue in high-altitude and cold areas. Comput. Biol. Med. 133, 104413 (2021).

Kotsiantis, S., Zaharakis, I. & Pintelas, P. Supervised machine learning: a review of classification techniques. Informatica 31(3), 501–520 (2007).

McDonald, A., Lee, J., Schwarz, C. & Brown, T. Steering in a random forest: Ensemble learning for detecting drowsiness-related lane departures. J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 56, 986–998 (2013).

Garcés, C., Orosco, L. & Laciar, E. Automatic detection of drowsiness in EEG records based on multimodal analysis. Med. Eng. Phys. 36(2), 244–249 (2014).

Sandberg, D., Akerstedt, T., Anund, A., Kecklund, G. & Wahde, M. Detecting driver sleepiness using optimized nonlinear combinations of sleepiness indicators. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 12(1), 97–108 (2011).

Awais, M., Badruddin, N. & Drieberg, M. A hybrid approach to detect driver drowsiness utilizing physiological signals to improve system performance and wearability. Sensors 17(9), 1991. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17091991 (2017).

Jo, J., Lee, S., Park, K., Kim, I. & Kim, J. Detecting driver drowsiness using feature-level fusion and user-specific classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 41((4 Part 1)), 1139–1152 (2014).

Lee, B., Lee, B., Chung, W. Smartwatch-based driver alertness monitoring with wearable motion and physiological sensor. In Proc. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. EMBS 11 6126–6129 (2015).

Sun, W., Zhang, X., Peeta, S., He, X., Li, Y. A real-time fatigue driving recognition method incorporating contextual features and two fusion levels, Transportation Research Board, 96th Annual Meeting 1–13 (2017).

Zhao, C., Zhao, M., Liu, J. & Zheng, C. Electroencephalogram and electrocardiograph assessment of mental fatigue in a driving simulator. Accid. Anal. Prev. 45, 83–90 (2012).

Murata, A. Proposal of a method to predict subjective rating on drowsiness using physiological and behavioral measures. IIE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 3, 7323 (2016).

Wang, M. et al. Drowsy behavior detection based on driving information. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 17(1), 165–173 (2016).

Ji, Q., Zhu, Z. & Lan, P. Real-time nonintrusive monitoring and prediction of driver fatigue. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 53, 1052–1068 (2004).

Ji, Q., Lan, P. & Looney, C. A probabilistic framework for modeling and real-time monitoring human fatigue. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. A 36, 862–875 (2006).

Yang, G., Lin, Y. & Bhattacharya, Pr. A driver fatigue recognition model based on information fusion and dynamic Bayesian network. Inf. Sci. 180, 1942–1954 (2010).

Yang, J., Tijerina, L., Pilutti, T., Coughlin, J. & Feron, E. Detection of driver fatigue caused by sleep deprivation. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 39(4), 694–705 (2009).

Murphy, K. Dynamic bayesian networks. In Probabilistic Graphical Models. Retrieved from (ed Jordan, M.) (2002).

McDonald, A., Lee, J., Schwarz, C. & Brown, T. A contextual and temporal algorithm for driver drowsiness detection. Accid. Anal. Prev. 113, 25–37 (2018).

Oshima, M. Fatigue Research 2nd edn. (tong fang shu yuan, 1979).

Wu, Q. Study on driving fatigue detection method based on ECG signal 6–31 (Zhejiang University, 2008).

Chen, S. et al. Information fusion and multi-classifier system for miner fatigue recognition in plateau environments based on electrocardiography and electromyography signals. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. 211, 106451 (2021).

Li, X. Research on security risk modeling method and application of space system based on Bayesian Network (National University of Defense Technology, 2016).

Cheng, J., Xu, K., Chen, S. & Xu, X. Risk analysis of leakage and explosion of ammonia refrigeration system based on Fuzzy-DBN. Saf Environ. Eng. 27(5), 147–164 (2020).

Lal, K. & Craig, A. A critical review of the psychophysiology of driver fatigue. Biol. Psychol. 55, 173–194 (2001).

Vysoky, P. Changes in car driver dynamics caused by fatigue. Neural Netw. World 14, 109–117 (2004).

Tal, O. & David, S. Driver fatigue among military truck drivers. Transp. Res. Part F3 3, 195–209 (2000).

Chen, S. et al. Linear and nonlinear analyses of normal and fatigue heart rate variability signals for miners in high-altitude and cold areas. Comput. Methods Progr. Biomed. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105667 (2020).

Lin, Y., Zhang, W. & Watson, L. Using eye movement parameters for evaluating human–machine interface frameworks under normal control operation and fault detection situations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 59, 837–873 (2003).

Wierwille, W., Ellsworth, L., Wreggit, S., Fairbanks, R., Kirn, C. Research on vehicle-based driver status/performance monitoring: development, validation, and refinement of algorithms for detection of driver drowsiness. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Final Report: DOT HS 808247, (1994).

Wylie, C., Shultz, T., Miller, J., Mitler, M., Mackie, R. Commercial motor vehicle driver fatigue and alertness study: Technical summary, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, Washington D.C., Tech. Rep. FHWA-MC-97–001, TC Rep. TP 12876E, Nov. (1996).

Yuan, Z. et al. Probabilistic assessment of visual fatigue caused by stereoscopy using dynamic Bayesian networks. Acta Ophthalmol. 97, 435–441 (2019).

Duda, R., Hart, P. & Stork, D. Pattern Classification 2nd edn. (Wiley, 2001).

Fukunaga, K. Introduction to statistical pattern recognition (Academic Press, 2013).

Picard, R., Vyzas, E. & Healey, J. Toward machine emotional intelligence: analysis of affective physiological state. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 23(10), 1175–1191 (2001).

He, C. & Zhao, C. Evaluation of the critical value of driving fatigue based on the fuzzy sets theory. Environ. Res. 61, 150–156 (1993).

Healey, J. Wearable and Automotive Systems for Affective Recognition from Physiology, Doctoral Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2000).

Li, X. & Ji, Q. Active affective State detection and user assistance with dynamic Bayesian networks. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part A 35, 93–105 (2005).

Pierre, T. & Jacques, B. Monotony of road environment and driver fatigue: a simulator study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 35, 381–391 (2003).

Zhang, Y. & Ji, Q. Active and dynamic information fusion for facial expression understanding from image sequences. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 27, 699–714 (2005).

Li, W. Research on situation estimation Technology in Information Fusion System (University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, 2004).

Zhang, A., Zhao, Z., Wang, Y. Estimating VDT visual fatigue based on the features of ECG waveform, in: International Workshop on Information Security and Application (IWISA), pp.446–449 (2009).

Patel, M. et al. Applying neural network analysis on heart rate variability data to assess driver fatigue. Expert Syst. Appl. 38(6), 7235–7242 (2011).

Awais, M., Badruddin, N. & Drieberg, M. A hybrid approach to detect driver drowsiness utilizing physiological signals to improve system performance and wearability. Sensors 17, 1–16 (2017).

Zhang, C., Wang, H. & Fu, R. Automated detection of driver fatigue based on entropy and complexity measures. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 15, 168–177 (2014).

Tian, L., Li, J. & Li, Y. Analysis of driving fatigue characteristics in cold and hypoxia environment of high-altitude areas. Big Data. 11(4), 255–267 (2023).

Sun, H. & Jia, A. Study on the development process of apron controller’s work fatigue based on heart rate characteristics. Heliyon. 10, e26296 (2024).

Mietkiewicz, J., Abbas, A. & Amazu, C. Enhancing control room operator decision making. Processes. 328(12), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12020328 (2024).

David, A., Mauricio-Andres, Z., Jorge, A. & Jorge, G. Visual analysis of fatigue in Industry 4.0. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 133, 959–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00170-023-12506-7 (2024).

Dai, L., Li, Y. & Zhang, M. Detection of operator fatigue in the main control room of a nuclear power plant based on eye blink rate. PERCLOS Mouse Veloc. Appl. sci. 13, 2718. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042718 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous referee and the editor for their helpful suggestions and insightful comments, which have significantly improved the content and presentation of the paper. The authors wish to express thanks to the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 52364009, 52374118 and 52264005), PhD Fund Project of Guizhou University (Guizhou University Renjihe Zi (2022) No. 63) , Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science) (No. Qian Ke He Ji Chu-ZK [2024] Yi Ban 098) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2018YFC0808406).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China,52364009,52374118,52264005,PhD Fund Project of Guizhou University,Guizhou University Renjihe Zi (2022) No. 63,Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science),Qian Ke He Ji Chu-ZK [2024] Yi Ban 098,National Key Research and Development Program of China,2018YFC0808406.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shoukun Chen: conceived of the study, designed the study and collected the data, performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. Liya Pan: collected the data, analyzed data. Kaili Xu: guided the writing process, designed the study and collected the data, performed the research, analyzed data. Xijian Li: designed the study, performed the research, analyzed data. Yujun Zuo: designed the study, performed the research, analyzed data. Zheng Zhou: collected the data, analyzed data. Bin Li: designed the study, performed the research, analyzed data. Zhangyin Dai: collected the data. Zhengrong Li: collected the data. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki guidelines and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Northeastern University (23–2019-0105).

Consent to participate declaration

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish declaration

Informed consent from all subjects for publication was obtained.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, S., Pan, L., Xu, K. et al. Real-time monitoring and prediction of remote operator fatigue in plateau deep mining based on dynamic Bayesian networks. Sci Rep 15, 1063 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85316-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85316-4