Abstract

Recently, it has been shown that sugar‑conditioned honey bees can be biased towards a nectarless dioecious crop as kiwifruit. The challenges for an efficient pollination service in this crop species are its nectarless flowers and its short blooming period. It is known that combined non-sugar compounds (NSCs) present in the floral products of different plants, such as caffeine and arginine, enhance olfactory memory retention in honey bees. Additionally, these NSCs presented in combination with scented food improve pollination activity in nectar crops. Here, we evaluated the effect of kiwifruit mimic-scented sugar solution (KM) on colonies located in this crop by supplementing them either with these NSCs individually (KM + CAF, KM + ARG), or combined (KM + MIX). Our results show an increase in colonies’ activity after feeding for all treatments. However, the colonies supplemented with the combined mixture (KM + MIX) collected heavier kiwifruit pollen loads and showed an increasing pollen stored area in their hives compared to the KM-treated control colonies. Unexpectedly, the caffeine-treated colonies showed a decrease in the pollen foraging related responses. These results show a combined effect of NSCs that improves honey bee pollen foraging in a nectarless crop, however this activity is impaired when caffeine is used alone for a nectarless crop.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well established that most of the main monocultures of fruits, vegetables and seeds globally increase their production through animal pollination and many of them depend on the pollination service provided by the management of the honey bee Apis mellifera1,2. However, the demand for managed pollinators has increased3,4, which forces a reevaluation of techniques to improve honey bee pollination efficiency in commercial crops.

Targeted pollination strategy, based on in-hive social learning, has been shown to be successful in various pollinator-dependent crops, such as sunflower, pear, apple and almond5. This consists of conditioning bees to sugar-rewarded mixtures of odorants that imitate the floral scent of target crops, thus biasing their foraging preferences towards them, increasing their yields. The mentioned crops have flowers that offer pollen along with nectar as a reward, a factor that promotes foragers to continue visiting these flowers.

Interestingly, the targeted pollination procedure was successful in guiding honey bees to crops with nectarless flowers as well, such as the case of kiwifruit Actinidia chinensis var. delicious6. This functionally dioecious species presents staminate (male) and pistilate (female) flowers offering pollen and pseudopollen (non-viable7), respectively, as reward8. In this agroecosystem, bees are essential to ensure pollination, transferring pollen from staminate flowers to pistillate flowers9,10. However, their lack of nectar decreases the attraction of honey bees to kiwifruit flowers compared to alternative nectariferous flora in the surrounding11,12. Nevertheless, it has been reported that beehives supplied with a synthetic mixture of kiwifruit mimetic odorants diluted in sugar syrup, collected more kiwifruit pollen than control hives6 suggesting a potential biased foraging preference towards this crop.

Additionally, it is known that a wide variety of non-sugar chemical compounds are present in the nectar and pollen of many plant species13, and some of these non-sugar compounds (NSCs) present potentially beneficial effects for both plants and pollinators14. This is the case of the alkaloid caffeine (CAF) and the aminoacid arginine, in its left-handed form “L-arginine” (ARG) which are present in the nectar and pollen of flowers of different angiosperm species15,16,17. CAF is present in fruits, seeds and leaves of many plant species18, protecting these structures against insect attack and preventing the germination of adjacent seeds19. However, at trace concentrations, its aversive effect in Apis mellifera disappears, and it can enhance the establishment of long-term olfactory memories (LTM) by potentiating responses of high-order neurons involved in olfactory learning and memory of the honey bee brain15. CAF has also been proposed as an enhancer of the appetitive behavior of the honey bee, which is manifested in greater foraging activity and recruitment of conspecifics towards new food sources through intensifying honey bee dances in active foragers20. ARG, on the other hand, is an aminoacid that participates in the synthesis of nitric oxide, which is involved in the formation of LTM in Apis mellifera21,22,23. Additionally, this compound has a positive effect on the formation of short-term memory, if administered at low concentrations24,25. This essential aminoacid also acts by preventing the presence of parasites in insects26. and improves the immune response at the cellular level27.

Furthermore, the oral administration of these combined two NSCs in field-realistic doses improves olfactory memory retention in honey bees subjected to classical olfactory conditioning laboratory assays28. Differential effects were obtained when the compounds were administered separately or combined, being the latter one that showed the best learning performances in harnessed bees. The use of NSCs was also evaluated under field conditions, in which food (sugar solution) scented with a synthetic mixture that mimics the sunflower inflorescence odor and supplemented with these compounds (CAF and ARG), showed an increase in foraging activity by honey bees in the sunflower crop and even in yield29.

However, whether the use of NSCs under field conditions might enhance foraging related activity in a nectarless dioicous crop is still an open question. In the present field study, we report the effect of offering KM-scented food supplemented with NSCs on the pollination service provided by honey bees in a kiwifruit crop. We fed colonies with KM-scented food (as a control group), and KM-scented food supplemented with either CAF, ARG, or a mixture of both, in field realistic doses13,15, and assessed foraging related activity on the crop. It is proposed that the joint administration of synthetic mimic odors of the target crop in combination with these NSCs, which act as memory enhancers, could further improve bee pollination efficiency in this nectarless crop.

Results

Colony activity and kiwifruit pollen collection

The effect of the kiwifruit mimic-scented sugar solution on colony activity was analyzed within the experimental period (Fig. 1). Thus, the number of incoming bees at the hive entrance per unit time, showed no signiticant differences among treatments within the measuring time (Fig. 1A, Table S1, Wald Chi-square statistic = 5.5263, p-value = 0.13707), but increased significantly after feeding the colonies irrespective of the treatment offered (Fig. 1B, Table S2, p-value < 0.0001). Focussing on pollen foraging, we analyzed the amount of white pollen loads collected, corresponding to kiwifruit (see “Materials and Methods”), both in absolute and relative terms, and found significant differences among treatments (Fig. 2A,B, Table S1, Wald statistics = 37.6867; 30.1284 respectively, p-values < 0.0001). The number and proportion of kiwifruit pollen loads did not differ between the control group KM and the colonies treated with KM + ARG and KM + MIX; however, those colonies treated with the synthetic odorant mixture plus CAF (KM + CAF) collected significantly lower amounts of white pollen loads (Fig. 2A,B; Table S3A,B, p-values < 0.05). When the weight of each corbicular load of kiwifruit pollen was estimated, significant differences were obtained among treatments (Fig. 2C, Table S1, Wald statistic = 8.0033, p-value = 0.045943). The size of the pollen loads for those colonies treated with KM + MIX resulted larger than those from the KM-control group. In contrast, treatments with only CAF or ARG resulted in lower outcomes compared to their combination (see Table S3C).

Effect of kiwifruit mimic-scented food on colony activity. Colonies were stimulated with kiwifruit mimic scented sucrose solution (KM) or KM-scented sucrose solution plus nectar nonsugar compounds presented individually (caffeine or l-arginine; KM + CAF, KM + ARG, respectivelly) or both combined (KM + MIX). (A) The number of incoming bees per minute was monitored per treatment. Boxplots show the median and interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers showing the maximum value within 1.5 IQR, and individual points mark values outside this range. (B) The number of incoming bees per minute was monitored up to 3 days post-stimulation. Circles indicate the mean values and bars show the 95% confidence intervals. The number of colonies evaluated is shown in parentheses. Letters indicate significant differences between measurement days (Supplementary Table S2). Green arrow indicates the moment of colony stimulation.

Effect of kiwifruit mimic odor and nectar nonsugar compounds on the collection of kiwifruit pollen. The number and proportion of trapped kiwifruit (white) pollen loads were monitored up to three days after feeding colonies with kiwifruit mimic scented sucrose solution (KM) or KM-scented food containing individually nectar non-sugar compounds, caffeine or l-arginine, or combined (KM + CAF, KM + ARG, KM + MIX; A, B). The weight of each kiwifruit pollen load was also estimated (C). Letters indicate significant differences between treatments (see Table S3). Squares indicate the mean values and bars show the 95% confidence intervals. The number of colonies evaluated is shown in parentheses.

Colony pollen storage

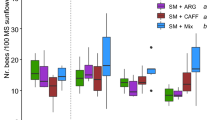

The amount of stored pollen in each hive was measured the day before the administration of the treatments (initial area) and 8 days later (final area). Despite an initial lack of pollen reserves in all hives, the applied treatments showed a significant change on the stored pollen area after stimulation depending on the treatment (Kruskal–Wallis test: p-value < 0.05, Fig. 3). Increasing stored pollen areas within the experimental period were observed for all colony groups, although those treated with NSCs (i.e., KM + ARG, KM + CAF and KM + MIX), showed higher values compared with the control colonies (KM). However, such increment resulted significant only in the case of colonies treated with the mixture of NSCs (KM + MIX, Table S4, p-value < 0.05).

Effect of kiwifruit mimic odor and nectar nonsugar compounds on the amount of stored pollen in honey bee colonies. Colonies were stimulated with kiwifruit mimic scented sucrose solution (KM) or KM-scented sucrose solution containing individually nectar non-sugar compounds, caffeine or l-arginine, or combined (KM + CAF, KM + ARG, KM + MIX). The total pollen area of beehives was assessed the day before applying the treatments and 8 days afterwards. Boxplots show the median and interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers showing the maximum value within 1.5 IQR, and individual points mark values outside this range. Letters indicates significant differences between treatments obtained by performing post-hoc comparisons (Table S2).

Discussion

Our study supports the potential use of NSCs as supplements for a targeted pollination strategy in kiwifruit with the aim to improve honey bee pollination services in a nectarless dioecious crop, evinced by an increase in the weight of kiwifruit pollen loads collected and in the total hive-stored pollen during the experimental period.

Firstly, when assessing the impact of offering colonies KM-scented food supplemented with NSCs on their activity at their hive entrances, no significant differences were detected among the treatments. However, a significant increase was observed in the number of incoming bees following the stimulation event for all treated colonies. These results align with those reported in field assays conducted on sunflower crops29, where, similar to this study, honey bee colonies exhibited increased foraging related activity after being stimulated with scented-food supplemented with NSC. Similar foraging patterns were also recently observed for honey bee colonies supplemented with KM-scented food in a kiwifruit crop6.

The first unexpected result was that the colonies supplied with KM + CAF showed a decrease in pollen collection, which was reflected in significantly lower quantities and proportions of kiwifruit pollen loads collected. This finding contrasts with previous studies on nectar collection in bees when exposed to CAF (honey bees20, bumble bees30). On the other hand, the KM + MIX treated colonies showed an increase in the weight of the collected kiwifruit pollen loads, being the only treated group that showed significant differences compared to the control group KM. Additionally, significant changes in the area of stored pollen were also recorded for the KM + MIX treated colonies, being once again the ones that presented a greater amount of reserves in their hives after the experimental period.

The result that honey bees treated with KM + CAF collected significant lower amounts of kiwifruit pollen is surprising, given the well-known boosting effects of this alkaloid at field-realistic concentrations, in terms of resource collection20,30, cognitive abilities15,28, benefits on vitality of honey bees31 and their conditions as an antioxidant32,33,34. Hence, considering these factors, it is expected that following CAF administration, inactive foragers would be stimulated to begin searching for immediate energy resources, such as nectar. However, no studies to date have linked boosting compounds like CAF, at the dose used here, to resources other than carbohydrates.

Based on the palynological analysis carried out in this work and prior research on this crop9,35, only the white loads collected were considered as kiwifruit pollen loads, although some works mention that pollen loads from male flowers are white, while those from female flowers are a white-yellowishshade, reporting an increase in the number of mixed loads as flowering progresses12. Due to the challenge of differentiating between white and white-yellowish shades, despite having perfomed a microscopic palynological study of flowers and pollen loads, there may have been an underestimation of the amounts of kiwifruit pollen collected by bees from the crop. Additional studies to distinguish the type of pollen collected, as well as monitoring the bees in the crop, would allow us to elucidate accurately the origin of the pollen loads and additionally determine if the activity of honey bees presents a bias towards one of the two floral types of kiwifruit (female or male) after KM stimulation.

Recently, it has been observed that honey bee colonies feed with KM-scented sugar solution showed enhanced kiwifruit pollen collection, suggesting a biased preference towards the target crop6. In the present study, we built upon this previous work by adding a mixture of CAF and ARG to the mimic odor KM. We observed that this additional supplementation increases the amount of kiwifruit pollen collected in terms of the pollen load size produced by the foragers. Regarding this aspect, colonies treated with KM + MIX showed the highest weights of the unit load of kiwifruit pollen, unlike what was obtained for the colonies supplemented with each NSC separately. This effect due to the NSCs mixture, which was not visualized with the individual compounds, was also reported for learning assays under controlled experimental conditions28 and when evaluating the foraging activity of honey bees stimulated with such NSCs together with scented food in a sunflower crop29, indicating a possible additive effect in the responses observed when the combination of both is present. This phenomenon could be linked to the positive effects that these compounds simultaneously have on the formation of long-term and stable memories through different pathways in the bee brain.

It has already been described that the weight of the unit loads of pollen collected by pollinators increases during the flowering period (bumble bees36, honey bees37), proposing in these reports that learning would be involved in motor skills related to the extraction and collection of pollen from flowers by pollinating insects36,38,39. The results found in this study could indicate that the mixture of CAF and ARG, supplied together with the KM-scented food, would have a positive effect on associative learning, manifesting itself in a more efficient kiwifruit pollen collecting activity, and therefore, in an increase in the weight of the pollen loads collected.

Regarding the variation in the stored pollen area, the colonies treated with KM + MIX significantly increased their pollen reserves during the experimental period compared to the control colonies. In contrast, pollen reserves of the groups treated with the non-sugar compounds offered individually did not differ from the control group KM. It was expected that both CAF, as a booster of collecting behaviors20,30 and ARG, due to its role as a precursor in the synthesis of compounds that promote the development of long-term memories such as nitric oxide21,22, could have a positive impact on the pollen reserve level of the treated hives. However, Couvillon and collaborators20 have also reported, when feeding with sugar solution supplemented with CAF traces, decreases in honey reserves levels in the hives, as a result of an overestimation of the resource offered under these experimental conditions. On the other hand, previous works highlight the positive effect of ARG on the formation of short-term rather than long-term memories24,25, so it is likely that the colonies fed with this non-sugar compound by itself did not show high levels of pollen reserves at the end of the experimental period, due to the short duration of the effect that the supplement may have had on the retention of learned information in bees. Once again, a differential effect was observed between non-sugar compounds when offered individually or together, being the latter the only one that seems to show a positive effect on pollen reserves, suggesting a possible combined effect of CAF and ARG on the neural network system that links the incorporated associative memories, which causes greater storage of this resource.

In addition, new evidence was obtained indicating that honey bee colonies treated with CAF decrease their pollen collecting activity, proving not to be a boosting factor in that activity as reported in previous studies20,30. It is worth noting that the CAF dose used in this study is considered field-realistic and has been already used in laboratory and field related studies with honey bees15,20,28,29. Future research should explore how CAF, when provided alongside a mixture of odors mimicking the floral scent of kiwifruit, affects the appetitive behaviors of bees in contexts where the primary available resource is not carbohydrates. When supplied simultaneously, these NSCs once again demonstrated differential and additive effects compared to their individual presentation on bee behavior. These effects were observed in activities conducted both inside and outside the hive, since an increase in the efficiency of pollen collection by these pollinators in the crop was obtained, which was reflected in the increase in the size of the kiwifruit pollen loads collected, and on the other hand, an increase in the storage of this resource within the hives was observed. The latter is particulary interesting, taking into account that these insects process, in addition to information based on individual experiences, resulting from informational exchange among conspecifics within their colonies40. Hence, collective-scale effects could be observed when these combined NSCs are offered. However, more studies are needed to address this aspect.

In conclusion, the present results represent an advance in the development of tools that increase pollination efficiency in nectarless crops, and open new questions for future research addressing the effect of these NSCs on the neural networks related to honey bee learning and memory.

Materials and methods

Study site, animals and chemical compounds

Field activities were carried out in a commercial kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa (A. Chev.) A. Chev.) 10-ha orchard, ‘Dos Abriles’, near Navarro, province of Buenos Aires, Argentina (33°47′48″S, 59°44′13″W), during the blooming season of 2021. The producers of this orchard interplanted vines of female cultivar Hayward with vines of male cultivars Chico malo, Matua, Tomuri and Chieftain. During the experimental period, wild flora such as Fabaceae and Asteraceae were present in the surrounding area. Crop under study consisted of 3 plots planted with female and male vines mentioned above intermixed within a 5-ha area. The measurements and sampling described below were carried out for four consecutive days between 10 am and 6 pm. Sixty Langstroth-type honey bee (Apis mellifera) hives located at the edges of the crop to provide pollination services (Fig. S1). Each hive had 10 frames, a fertilized queen, between 4 and 6 brood frames, a limited food reserve and had similar population level (around 20,000 individuals). They were entered into the culture between 1 and 4 days prior to the beginning of the measurements (this fact was considered in the statistical analyses performed as late and early arrival respectively, see “Hive arrival” variable in Table S1). The hives were divided into 4 equal groups, 1 for each treatment provided (see below “Hives stimulation”), located at approximately 100 m from each other to avoid the drift of individuals belonging to different experimental groups. They were located within the crop in such a way as to guarantee similar floral availability between groups. The level of flowering in the crop during the measurement days post-stimulation (Fig. S2) was estimated as the percentage of open flowers (number of open flowers per branch / total number of flowers per branch). This was done once per day, on 30 randomly selected plants per batch (15 males and 15 females).

The palynological analyses and sample processing were carried out during December 2021 in the Social Insects Laboratory located in the Experimental Field of the Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences of the UBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina. The chemical compounds used in the preparation of the treatments to be applied to the hives were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany. A kiwifruit formulation developed in our laboratory was used41. The concentrations of CAF and ARG used (see the section below) are within the range of values present in the nectars of different floral species13,15. Additionally, they improved learning performance, facilitated stable and long-term olfactory memory processes and enhanced survival under controlled experimental conditions28. These concentrations were also applied in a related field study with positive effects both on honey bee foraging and on crop yield29.

Hives stimulation

Scented food was prepared by diluting 50 μl of the synthetic kiwifruit mixture (KM) per liter of 50% w/w sucrose solution. From this solution, 4 treatments were prepared: KM (control group), KM + Caffeine [0.15 mM] (KM + CAF), KM + L-Arginine [0.03 mM] (KM + ARG) and KM + Mixture of Caffeine and L-Arginine (KM + MIX). Twelve honey bee colonies per treatment were fed at the end of the first day of the experimental period by pouring 500 ml of one of these scented sugar solutions over the frames of the hives.

Colony activity and kiwifruit pollen collection

In order to study the effect of providing colonies with KM scented food supplemented with NSCs on their activity, the total number of incoming bees on each hive entrance was quantified over a 1-min period, twice daily throughout the 4-day experimental period (1 day pre-stimulation and 3 days post-stimulation).

On the other hand, to assess the impact on their pollen foraging, 8 conventional frontal pollen traps per treatment were placed at the entrance of the experimental hives, so as to be able to access the type and amount of pollen collected by each one. These traps consist of a wooden structure that is assembled at the entrance of the hive, a metal mesh through which the foraging bees must necessarily enter tightly, releasing their loads of pollen, which fall into a container. Pollen sampling was carried out once a day, during 3 h, on the 4 days of field work. Samples were stored in a freezer at − 20 °C and were subsequently analyzed in the laboratory. The total number of loads collected per hive was quantified, weighed and separated according to their color. The proportion of white loads collected (defined as the number of white loads/total number of loads) and the weight per unit white load (as the total weight of white loads/number of white loads) were stimated (i.e., the number of white loads for each treatment was: KM, 1288; KM + CAF, 96; KM + ARG, 372; KM + MIX, 1393). Identity of white pollen samples was verified under microscope by comparing them with pollen preparations from kiwifruit flower anthers, taken in the field6,9,42.

Colony pollen storage

In order to analyze the effect of feeding colonies KM-scented food supplemented with NSCs on nest pollen reserves, we estimated the amount of stored pollen in each hive the day before the administration of the treatments (initial area) and 8 days later (final area). Using a millimeter ruler, this area was measured on both sides of each frame of 8 hives per treatment.

Statistic analysis

All statistical analyzes were carried out using R v3.6.3 program43. Generalized linear models (GLM), generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) and statistical tests of the different analyzes were performed with the glmmTMB44, MASS45 and car46 packages. In each case, data´s good fit to the probability distribution chosen for the response variable was verified, as well as the absence of over- or under-dispersion in the data and patterns in the distribution of the residuals using the DHARMa package47. Non-significant variables were removed by comparing different models using the Drop1 function48, which uses the Akaike criterion (AIC) to make a balance between the goodness of fit of the model and its complexity49. The means of the different treatments were compared using an analysis of their variances (ANOVA50) and the relevant post hoc contrasts were carried out using the emmeans package51 following the Tukey method for multiple comparisons52. The effect of the treatment on colony activity was analyzed using a GLMM53 with a negative binomial error structure (due to overdispersion in the data). Pollen influx to the hives was analyzed using a GLMM with negative binomial (overdispersion) error structures for the number of white pollen loads collected, quasibinomial (overdispersion) for the proportion of kiwi fruit pollen collected and beta for the weight per unit load of pollen. Treatment applied (4 level factor), blooming level available (Fig. S2), absence or presence of traps in the measured hives and the day on which the measurement were considered as explanatory variables. In turn, the hive identifiers were added as a random factor and, for pollen influx, the trap collection time was incorporated into the models using the offset function to declare differences in sampling effort. Finally, after several transformations of the data, it did not fit a normal probability distribution for the response variable “Stored pollen post-stimulation”, which is why the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test was performed54 as analogous to ANOVA for non-normal data.

Statement on the experimental research and field studies

The producers of the studied kiwifruit orchard granted permission for plant measurements, which were done in situ. All methods and assays performed in this field study comply with national legislation and guidelines of the University of Buenos Aires and CONICET-Argentina.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

References

Klein, A. M. et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 274(1608), 303–313 (2007).

IPBES. Summary for policymakers of the assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services on pollinators, pollination and food production (eds Potts, S. G., Imperatriz-Fonseca, V. L., Ngo, H. T., Biesmeijer, J. C., Breeze, T. D., Dicks, L. V., Garibaldi, L. A., Hill, R., Settele, J., Vanbergen, A. J., Aizen, M. A., Cunningham, S. A. C.) (2016).

Aizen, M. A. & Harder, L. D. The global stock of domesticated honey bees is growing slower than agricultural demand for pollination. Curr. Biol. 19, 915–918 (2009).

Aizen, M. A. et al. Global agricultural productivity is threatened by increasing pollinator dependence without a parallel increase in crop diversification. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 3516–3527 (2019).

Farina, W. M., Arenas, A., Estravis-Barcala, M. C. & Palottini, F. Targeted crop pollination by training honey bees: Advances and perspectives. Front. Bee Sci. 1, 1253157 (2023).

Estravis-Barcala, M. C., Palottini, F., Verellen, F., González, A. & Farina, W. M. Sugar-conditioned honey bees can be biased towards a nectarless dioecious crop. Sci. Rep. 14, 18263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67917-7 (2024).

Schmid, R. Reproductive anatomy of Actinidia chinensis (Actinidiaceae). Bot. Jahrb. Syst. 100, 149–195 (1978).

Ferguson, A. R. Botanical description. In: The Kiwifruit Genome, Compendium of Plant Genomes (eds Testolin, R., Huang, H. W.) 1–13 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32274-2_1

Goodwin, R. M. Kiwifruit flowers: Anther dehiscence and daily collection of pollen by honey bees. New Zeal. J. Exp. Agric. 14(4), 449–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/03015521.1986.10423064 (1986).

Goodwin, R. M. Pollination of Crops in New Zealand and Australia (Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation, 2012).

Palmer-Jones, T. & Clinch, P. G. Observations on the pollination of Chinese gooseberries variety ‘Hayward’. New Zeal. J. Exp. Agric. 2(4), 455–458 (1974).

Jay, D. & Jay, C. Observations of honeybees on Chinese gooseberries (‘kiwifruit’) in New Zealand. Bee World 65(4), 155–166 (1984).

Baker, H. G. & Baker, I. Amino-acids in nectar and their evolutionary significance. Nature 241, 543–545 (1973).

Stevenson, P. C., Nicolson, S. W. & Wright, G. A. Plant secondary metabolites in nectar: Impacts on pollinators and ecological functions. Funct. Ecol. 31(1), 65–75 (2017).

Wright, G. A. et al. Caffeine in floral nectar enhances a Pollinator’s memory of reward. Science 339, 1202. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1228806 (2013).

Power, E. F., Stabler, D., Borland, A. M., Barnes, J. & Wright, G. A. Analysis of nectar from low-volume flowers: A comparison of collection methods for free amino acids. Methods Ecol. Evol. 9(3), 734–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12928 (2017).

Taha, E. A., Al-Kahtani, S. & Taha, R. Protein content and amino acids composition of bee-pollens from major floral sources in Al-Ahsa, eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 26(2), 232–237 (2019).

Myers, R. L. The 100 Most Important Chemical Compounds: A Reference Guide 55 (Greenwood Press, 2007). ISBN 978-0-313-33758-1.

Caballero, B., Finglas, P. & Toldrá, F. Encyclopedia of Food and Health (Academic Press, 2015).

Couvillon, M. J. et al. Caffeinated forage tricks honeybees into increasing foraging and recruitment behaviors. Curr. Biol. 25, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.052 (2015).

Müller, U. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase impairs a distinct form of long-term memory in the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Neuron 16, 541–549 (1996).

Müller, U. The nitric oxide system in insects. Prog. Neurobiol. 51, 363–381 (1997).

Müller, U. Prolonged activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase during conditioning induces long-term memory in honeybees. Neuron 27, 159–168 (2000).

Chalisova, N. I. et al. Effect of encoded amino acids on associative learning of honeybee Apis mellifera. Zhurnal Evolyutsionnoi Biokhimii i Fiziologii 47(6), 516–518. https://doi.org/10.1134/S0022093011060135 (2011).

Lopatina, N. G. The influence of combinations of encoded amino acids on associative learning in the honeybee Apis mellifera L. J. Evol. Biochem. Phys. 53(2), 123–128 (2017).

Rivero, A. Nitric oxide: An antiparasitic molecule of invertebrates. Trends Parasitol. 22(5) (2006).

Negri, P. et al. Nitric oxide participates at the first steps of Apis mellifera cellular immune activation in response to non-self recognition. Apidologie https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-013-0207-8 (2013).

Marchi, I. L., Palottini, F. & Farina, W. M. Combined secondary compounds naturally found in nectars enhance honeybee cognitionand survival. J. Exp. Biol. 224(6), jeb239616 (2021).

Estravis-Barcala, M. C., Palottini, F. & Farina, W. M. Learning of a mimic odor combined with nectar nonsugar compounds enhances honeybee pollination of a commercial crop. Sci. Rep. 11, 23918. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-03305-9 (2021).

Arnold, S. E. et al. Bumble bees show an induced preference for flowers when primed with caffeinated nectar and a target floral odor. Curr. Biol. 31, 1–5 (2021).

Strachecka, A. et al. Unexpectedly strong effect of caffeine on the vitality of western honeybees (Apis mellifera). Biochemistry (Moscow) 79(11), 1192–1201. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0006297914110066 (2014).

Lee, C. Antioxidant ability of caffeine and its metabolites based on the study of oxygen radical absorbing capacity and inhibition of LDL peroxidation. Clin. Chim. Acta 295(1–2), 141–154 (2000).

Kriško, A., Kveder, M. & Pifat, G. Effect of caffeine on oxidation susceptibility of human plasma low density lipoproteins. Clin. Chim. Acta 355(1–2), 47–53 (2005).

León-Carmona, J. R. & Galano, A. Is caffeine a good scavenger of oxygenated free radicals?. J. Phys. Chem. B 115(15), 4538–4546 (2011).

Delaplane, K. S. et al. Standard methods for pollination research with Apis mellifera. J. Apicult. Res. 52(4), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.52.4.12 (2013).

Raine, N. E. & Chittka, L. Pollen foraging: Learning a complex motor skill by bumblebees (Bombus terrestris). Naturwissenschaften 94, 459–464 (2007).

Díaz, P. C. et al. Honeybee cognitive ecology in a fluctuating agricultural setting of apple and pear trees. Behav. Ecol. 24(5), 1058–1067. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/art026 (2013).

Laverty, T. M. & Plowright, R. C. Flower handling by bumblebees: A comparison of specialists and generalists. Anim. Behav. 36(3), 733–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(88)80156-8 (1988).

Woodward, G. L. & Laverty, T. M. Recall of flower handling skills by bumble bees: A test of Darwin’s interference hypothesis. Anim. Behav. 44(6), 1045–1051 (1992).

Arenas, A., Lajad, R. & Farina, W. Selective recruitment for pollen and nectar sources in honeybees. J. Exp. Biol. 224(16), 242683. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.242683 (2021).

Farina, W. M., Palottini, F. & Estravis-Barcala, M. C. Formulation and composition which promote targeted pollination by bees towards kiwifruit crops and related methods. PCT/IB2022/058287. Patents pending. https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/es/detail.jsf?docId=WO2023031882&_cid=P11-M4E25N-43589-1 (2022).

De Piano, F. G., Meroi Arcerito, F. R., De Feudis, L., Basilio, A. M., Galetto, L., Eguaras, M. J., Maggi, M. D. Food supply in honeybee colonies improved kiwifruit ('Actinidia deliciosa Liang & Ferguson) (Actinidiaceae: Theales) pollination services. Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 80(3) (2021).

R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). https://www.R-project.org/(2021) (2021).

Brooks, M. E. et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 9(2), 378–400 (2017).

Venables, W. N. & Ripley, B. D. Modern Applied Statistics with S 4th edn. (Springer, New York, 2002).

Fox, J. & Weisberg, S. An R companion to applied regression 3rd edn. (Sage, 2019).

Hartig Florian. DHARMa: Residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level/mixed) regression models. R package version 0.3.3.0.https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (2020).

Chambers, J. M. Linear models. In Chapter 4 of Statistical Models in S (eds Chambers, J. M. & Hastie, T. J.) (Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole, 1992).

Sakamoto, Y., Ishiguro, M. & Kitagawa, G. Akaike Information Criterion Statistics (D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1986).

Kaufmann, J., & Schering, A. Analysis of variance ANOVA. In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118445112.stat0 (2014).

Lenth, R. Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squared means [accessed 2 February 2020]. Available from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html.

Tukey, J. W. Exploratory Data Analysis (Addison-Wesley Reading, 1977).

Bolker, B. M. et al. Generalized Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide for Ecology and Evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24, 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008 (2009).

Kruskal, W. H. & Wallis, W. A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 47, 583–621 and errata, ibid. 48, 907–911 (1952).

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the commercial orchard ‘Dos Abriles’ for its selfless support at the agricultural setting. Authors also thank the CONICET, the University of Buenos Aires and ANPCYT for financial support. This project received logistical support by Beeflow SAU.

Funding

This study was funded by Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Grant No. PICT 2019 2438), Secretaría de Ciencia y Técnica, Universidad de Buenos Aires (Grant No. UBACYT 2018 20020170100078BA), Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Grant No. PIP 112-201501-00633).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.M.F. conceived the research study and was responsible for the project administration and funding acquisition. All authors designed the experiments. All authors collected the data and supervised data collection. F. V. analysed the data. All authors wrote the manuscript and all authors edited it, and approved the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

National Scientific and Technical Research Council of Argentina (CONICET) and the University of Buenos Aires have filed the patent application (PCT/IB2022/058287) on the commercial use of the kiwifruit formulation to improve honey bee pollination efficiency, in which W.M.F., M.C.E.B. and F.P. are coinventors. W.M.F. is coinventor and shareholder of Beeflow Corporation, the licensee of this technology. F.V. declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Verellen, F., Palottini, F., Estravis-Barcala, M.C. et al. Sugar conditioning combined with nectar nonsugar compounds enhances honey bee pollen foraging in a nectarless diocious crop. Sci Rep 15, 1756 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85494-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85494-1