Abstract

This study introduces a hybrid data assimilation method that significantly improves the predictive accuracy of the time-dependent Susceptible-Exposed-Asymptomatic-Infected-Quarantined-Removed (SEAIQR) model for epidemic forecasting. The approach integrates real-time Ensemble Kalman Filtering (EnKF) with the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm, combining dynamic real-time adjustments with pattern recognition techniques tailored to the specific dynamics of epidemics. This hybrid methodology overcomes the limitations of single-model predictions in the face of increasingly complex transmission pathways in modern society. Numerical experiments conducted using COVID-19 case data from Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China (December 9, 2021, to January 8, 2022) demonstrate a marked improvement in forecasting accuracy relative to traditional models and other data assimilation approaches. These findings underscore the potential of the proposed method to enhance the accuracy and reliability of predictive models, providing valuable insights for future epidemic forecasting and disease control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid global spread of the novel coronavirus in 2019 triggered significant social and economic crises, prompting countries worldwide to implement emergency measures to contain the virus. This situation underscored the urgent need to establish a robust and quantifiable analytical system to mitigate the adverse impacts of future infectious diseases on society. Early investigations into the COVID-19 outbreak in China addressed this need by analyzing initial data1,2,3. As the pandemic progressed, Philip Nadler et al. first identified the limitations of single-model epidemiological frameworks4, which subsequently led to the application of data assimilation techniques to enhance the study of COVID-19 transmission.

The integration of data assimilation methods into infectious disease modeling has become increasingly crucial. Even with more flexible forecasting models, limitations in their predictive capabilities persist due to a lack of dynamism. The time-dependent Susceptible-Exposed-Asymptomatic-Infected-Quarantined-Removed (SEAIQR) model, an extension of the Susceptible-Infective-Removed (SIR) model5, incorporates temporal trends into epidemic progression by categorizing the population into multiple compartments to capture disease transmission dynamics. Although the inclusion of dynamic contact rate parameters improves predictive accuracy over traditional models, real-world scenarios often involve complex patterns of population interactions and stochastic epidemic control measures, resulting in more intricate and nonlinear disease evolution, thereby compromising predictive accuracy. Data assimilation techniques can rectify such issues by adjusting predictive data. Rhodes CJ et al. were pioneers in applying data assimilation methods to the SIR model for the study of influenza and other diseases6,7. Nonetheless, these methods are typically constrained to assimilating one-dimensional observational data, such as daily trend shifts, into the model. This limitation necessitates a more sophisticated data assimilation approach that can incorporate temporal trend variations over extended periods into predictive models.

The Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF) method has demonstrated superior performance in assimilating data for nonlinear systems8. It represents the system state distribution through a set of samples, and classical EnKF approximates the covariance matrix using ensemble-based stochastic updating methods. While this random update mechanism is effective for certain problems, it falls short of meeting the higher accuracy requirements in high-dimensional nonlinear scenarios. To address this shortcoming, Papadakis9proposed the Weighted Ensemble Kalman Filter (WENKF) method, which, in the context of infectious disease forecasting, has not sufficiently aligned with dynamic real-world conditions. In contrast, Lal R10introduced time-varying elements into epidemic prediction models and employed a Kalman filter with damping coefficients for data assimilation. This approach, while innovative, lacks the flexibility and stability necessary for handling complex epidemic dynamics. In this study, we propose a novel modification: a flexible weighting function designed to enhance the stability and fidelity of the data assimilation process to a greater extent. This work integrates WENKF with a hybrid data assimilation framework, combining real-time EnKF with the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) method. Unlike previous time-varying data assimilation approaches in infectious disease models4, this study is the first to explore real-time EnKF for data assimilation in such models, leveraging the high coupling between EnKF and the time-varying data assimilation framework. Furthermore, by incorporating KNN, the hybrid approach addresses issues related to ensemble divergence and sample validity during stochastic updates. The resampling of the weighting function improves the alignment of the ensemble with actual epidemic dynamics. In doing so, the study introduces epidemic dynamic adjustment patterns into the ensemble updating process of the EnKF, proposing a data assimilation method informed by dynamic adjustments based on empirical data.

Although existing methods have shown promise in specific contexts, they are generally limited by the imprecision in selecting time-varying parameters and their inability to adapt to the complexities of real-world conditions. The hybrid approach presented in this study overcomes these limitations by offering a more flexible and dynamic data assimilation framework. Future research should explore its adaptability across different regions or infectious diseases, particularly under conditions of initial parameter fluctuation.

In the data analysis section of this study, a comparative evaluation was conducted between the fundamental time-dependent SEAIQR model and traditional data assimilation techniques. The results demonstrate that integrating real-time EnKF with KNN significantly improves the predictive accuracy of the assimilation model, highlighting the efficacy of the hybrid approach in epidemic forecasting.

Data sources

The epidemic data was sourced from the Infectious Disease Surveillance System within the “China Disease Control and Prevention Information System,” covering the real time epidemic monitoring in Xi’an from December 9, 2021, to January 8, 2022.

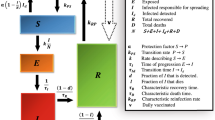

Time-dependent SEAIQR model

The time-dependent SEAIQR model11,12,13 incorporates multiple state categories, allowing for a more precise representation of the disease transmission dynamics.This model is an extension of the SEIR model, known as the time-dependent SEAIQR model, which includes two additional compartments: asymptomatic infected individuals (A) and quarantined (Q). This model incorporates improvements such as isolation and recovery states, as well as time-varying factors related to actual epidemic control measures. The system of differential equations for this model is given by Equations 1:

Eqs.1 simulates the evolution of key parameters using a time-series model. The initial conditions and parameter settings of the key parameters in Eqs. 1 are provided in Table 1.

Data assimilation scheme for the time-dependent SEAIQR model

Initial data processing

To account for errors in epidemic observations and to better simulate real epidemic data, reasonable perturbations are introduced to the initial epidemic observation data set W to reflect factors such as nucleic acid testing errors, thereby aligning the data more closely with actual values. The processed observation data is then used as the true values. The false positive rate of nucleic acid testing in China during this timeframe was \(0.23\%\)12.In this study, nucleic acid testing errors are incorporated into the observation error covariance matrix \(R_{w}\) and the observation operator H. The initial forecast error covariance matrix Pis based on the initial error parameters derived from using only the SEAIQR model13 during this epidemic period.

EnKF and KNN methods

Ensemble Kalman Filtering (EnKF) is a data assimilation technique used to estimate the state of a dynamic system from noisy and incomplete observations. Unlike traditional Kalman filters, which rely on a single estimate of the system state, EnKF uses an ensemble of model states to represent the uncertainty in the system. The method updates the ensemble by incorporating real-time observational data, thereby improving the model predictions. EnKF is widely used in fields such as weather forecasting, climate modeling, and epidemiology, where the system is governed by complex, nonlinear dynamics, and real-time observations are available.The process of classical EnKF is described by the following equations

The Eq. 2 represents the data prediction process, while Eqs. 3 to 6 describe the data update process. The EnKF achieves optimized prediction by alternately iterating through prediction and update steps, coupling the observations with the predicted values.

K-Nearest Neighbors is a simple yet effective machine learning algorithm commonly used for classification and regression tasks. Its fundamental idea is to make predictions or classifications based on the proximity of samples in the feature space. Specifically, if a sample’s nearest neighbors in the feature space predominantly belong to a particular class, then the sample is likely to belong to that class as well. The basic procedure is as follows, with the training and testing sets remaining in standard format:

Here, D represents the training set, and \(X^l\) denotes the test set. By selecting k nearest points near the test set, the degree of association is assessed using the following formula:

In this study, the classification conditions of the KNN method are integrated with actual epidemic trends, using metrics such as the number of close contacts and the scope of isolation as classification indicators. The classification indicator \(\alpha\)is derived from studies on the actual number of contacts and isolated individuals within the same social context14,15,16. \(\alpha\) is an empirical function encompassing response attributes, which is further derived from \(\alpha _0,\alpha _1,\dots ,\alpha _{t_{days}}\). Here, \(\alpha _i\) represents response indicators observed under similar social contexts, it follows that

Using the number of days in the empirical observation period as the independent variable for the time-varying function \(\alpha\), and use empirical observation days as interpolation nodes, the Newton interpolation method is applied to interpolate \(\alpha _i\), resulting in the empirical function of the indicator parameters.

Differentiating the empirical Eq. 12 yields the response indicators:

This yields \(\alpha\),

Real time data is classified based on the indicator \(\alpha\) with the first category having the following interval:

In Eqs. 14 and 15, \(p_{1\min }\) and \(p_{1\max }\) represent the time-varying weight ranges. This interval is used to generate a normal distribution for the training set \(X_1\) that satisfies the EnKF requirements.

Similarly, the training set \(X_{2}\) the second group of exclusion intervals is generated as follows in Eqs. 18 to 21.

In this context, the return value for the first category data is denoted as 1, while the return value for the second category data is denoted as 0. The values of \(c_1\) , \(c_2\) , \(c_3\) and \(c_4\) can be optimized through iterative experimentation. This approach facilitates the classification function for the real-time EnKF’s random update component.In this subsection, KNN and time-varying parameter \(\alpha\) are used to obtain the real-time classification interval of the updated part of the real-time EnKF, so that the data assimilation process is preliminarily coupled with the KNN method.

A hybrid data assimilation method based on real-time Ensemble Kalman filtering and KNN

In practical scenarios, the number of individuals in isolation varies with changes in the number of close contacts and newly confirmed cases. At the analysis value update juncture, This inquiry introduces an ensemble processing component that adapts to this background, affecting both the forecast and analysis values according to their time-varying proportions. This adjustment makes the assimilation process more aligned with the actual problem context. In real-time EnKF, the random updates of the ensemble are replaced by time-varying updates.We obtained N ensembles in the stochastic update step of the EnKF

In Eq. 22, \(S_{i,k+1}\) denotes the number of susceptible individuals, \(Sq_{i,k+1}\) represents the isolated susceptible individuals, \(E_{i,k+1}\) corresponds to the exposed individuals, and \(Eq_{i,k+1}\) indicates the isolated exposed individuals. \(A_{i,k+1}\) refers to the asymptomatic cases, \(I_{i,k+1}\) accounts for the confirmed cases, \(H_{i,k+1}\) represents the hospitalized patients, and \(R_{i,k+1}\) signifies the recovered individuals. All these quantities are assessed at the time point \(k+1\) .

Within the context of social networks, changes in the number of confirmed cases and asymptomatic individuals can significantly affect isolation strategies. This impact is proportional to local response efficiency and public attention. In this analysis, the extent of government and societal response is embodied in parameter \(\lambda _{i,k+1}\) , which encompasses both computational and observational errors

To more appropriately integrate time-varying characteristics17 into the data assimilation process, a time-varying parameter \(\beta _{k+1}\)11 is introduced. In the following expression, \(\beta _{0}\) is the initial infection rate at the onset of the epidemic. t denotes the number of days since the onset of the epidemic, and r signifies the response rate, their variation is proportional to the number of days since the outbreak of the epidemic

By coupling parameter \(\lambda _{i,k+1}\) with parameter \(\beta _{k+1}\) as a weighting function in the real-time EnKF, the computational error of the latter is mitigated, and its time-varying properties are enhanced

In the random update step, each random update \(X_{i,k+1}^a\) is assigned a specific weight \(W_{i,k+1}\), which serves to evaluate the correlation between the random sets and the actual control measures. The weights of the N random sets are dynamically categorized. Sets falling into the first category are retained, with the number of retained sets denoted as \(N_{new}\), while those in the second category are discarded. As a result, the updated sets are as follows

Subsequently, the retained set undergoes resampling, initiated by calculating the cumulative weight of the \(X_{N_{new},k+1}^a\)

We generate an array containing \(N_{new}\) elements, such that each element \(u_{N_{new}}\) satisfies the following conditions

By incrementing m , replace the element at the first position in \(u_{N_{new}}\) that is not greater than \(CDF_m\) but is greater than \(CDF_{m-1}\) with the corresponding element from the original array. Repeat this process until all elements are replaced. Subsequently, perform averaging on the resulting final array set to obtain the optimized array \(\overline{X}^a_{k+1}\) and the prediction error covariance matrix \(P^{new}_{k+1}\) :

and

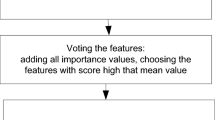

Figs. 1 and 2 illustrate the overall process of the hybrid method. The data from the predictive model is first output and simultaneously fed into the EnKF. Key information such as the number of infections and isolations is used to extract weights. These extracted weights are then classified using a KNN model trained with periodic parameters, resulting in weighted sets. Resampling methods are then applied to generate an optimized ensemble by combining high-weight sets with low-weight ones. Finally, the optimized ensemble is used to update the parameters in the EnKF, providing an updated prediction covariance matrix and refined forecast data. This process enables more accurate real-time predictions of key information, such as the number of infections.

A Hybrid Data Assimilation Method Based on Real-Time EnKF and KNN. (The classified target data, obtained through the introduction of classification criteria, is updated via resampling. This process selects high-weight particles while ensuring coverage of low-weight particles, thereby improving the performance of the new ensemble. The updated ensemble is then used as the input for the filtering update, facilitating the prediction process.).

Results

Data assimilation results

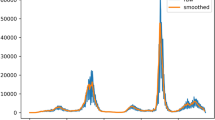

Denote the real-time EnKF assimilation method mentioned in this paper as R_EnKF. The assimilation results using the real-time EnKF and the KNN-based hybrid data assimilation method for Xi’an from December 9, 2021, to January 8, 2022, are shown in Fig. 3. Figs. 4 and 5 present the data assimilation results of the real-time EnKF and the EnKF under the same conditions.

In this context, \(u\_analysis\) represents the analysis values from the hybrid data assimilation, \(u\_pred\) represents the predicted values from the SEAIQR model, \(u\_w\) represents the real-time epidemic observation data, and \(u\_real\) represents the “true values” constructed by incorporating observation data and accounting for observational errors, including nucleic acid testing inaccuracies. The experimental results demonstrate that data assimilation methods incorporating time-varying attributes achieve superior accuracy compared to conventional EnKF methods. Additionally, this hybrid approach outperforms the singular real-time EnKF method, with its accuracy being contingent upon the precise selection of key parameters, which enhances its potential for application in contexts with ample statistical samples.

Comparison of errors under different time-varying parameters

To assess the impact of the accuracy of time-varying parameters on data assimilation performance, experiments were conducted in this section on \(\alpha\) under varying perturbation trends. During the data assimilation process, the classification intervals of its weight vectors are influenced by the time-varying parameter \(\alpha\) . Different control intensities applied to the time-varying parameter can affect the error in data assimilation. The most realistic time-varying parameter yields the best processing results. When using the parameter \(\alpha\) that most accurately reflects practical control conditions, the errors of the updated array \(X^{a}_{N_{new},k+1}\) under high and low weights during the active control phase are shown in Fig. 6.

When the time-varying parameter \(\alpha\) is increased, the weight classification will be disrupted, resulting in a weakened correlation between the errors carried by array \(X^{a}_{N_{new},k+1}\) and the time-varying weights. The errors will gradually detach from the context of social control, and the results will increasingly resemble those of the classical EnKF. This effect is illustrated in Fig. 7.

Reducing \(\alpha\) will cause the initial experience parameters \(c_1\) , \(c_2\) , \(c_3\) and \(c_4\) to dominate the classification metrics. If the initial metrics are selected ambiguously, it will severely impact the data assimilation results, similarly causing the data update process to lose real-time filtering effectiveness and leading to increased errors, as shown in Fig. 8.

In summary, the selection of \(\alpha\) is critical values that are excessively high or low will lead to increased errors and reduced accuracy of this hybrid data assimilation method.

Sensitivity analysis

Evaluation metrics are the mean absolute error (MAE) and the root mean squared error (RMSE), used to compare the assimilation effects of various data assimilation methods. The formulas for calculating MAE and RMSE are as follows

In this regard, \(y_i\) represents the actual values, \(\hat{y}_{i}\) represents the predicted values, and n represents the number of forecast days.

In practical applications, both MAE and RMSE quantify the discrepancy between predicted and actual values, and parameters can be systematically adjusted through methods such as gradient descent or the construction of inversion neural networks. MAE and RMSE provide quantitative guidance for optimizing model parameters, and through hyperparameter tuning techniques, they enable a focus on those parameters that significantly reduce error metrics. By evaluating the impact of different parameter configurations on model performance, key parameters can be adjusted to enhance predictive accuracy.

In Fig. 9, the vertical axis represents the error between data assimilation analysis values and observed values, while the horizontal axis denotes the days since the epidemic outbreak. Fig. 10 shows the comparison of different data assimilation methods during the period of enhanced government response.

The errors of different data assimilation methods are presented in Table 2, where “EnKF” refers to the EnKF method, “R_EnKF+KNN” denotes the hybrid method of real-time EnKF and KNN, “R_EnKF” represents the real-time EnKF method, “4DVAR+EnKF” is the hybrid method of Four-Dimensional Variational data assimilation and EnKF, “4DVAR+R_EnKF” denotes the hybrid method of Four-Dimensional Variational data assimilation and real-time EnKF, and time-dependent SEAIQR represents the basic predictive model.

To assess the uncertainty associated with the performance metrics of the predictive model, we computed the 95% confidence intervals for the MAE and RMSE values. A confidence interval provides a range within which we expect the true performance metric to lie with 95% probability, offering a more reliable estimate than a single-point value. The inclusion of confidence intervals is particularly important in our study, as it accounts for the inherent variability in model predictions across different parameter settings. Using the chi-squared distribution, we derived the 95% confidence interval for the MAE as [0.971, 2.649] and for the RMSE as [1.310, 2.248]. This statistical measure reinforces the validity of our model’s improvements and helps quantify the uncertainty in the reported performance enhancements.

The analysis results show that the real-time EnKF method proposed in this paper improves the prediction effect of the basic model and the single data assimilation model to a certain extent. On this basis, the hybrid method combined with the KNN algorithm further improves the prediction effect of the model, and the error is smaller than that of other mixed data assimilation methods. Compared with the traditional EnKF method, the hybrid data assimilation method reduces the model prediction error by 7.97%.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of the hybrid EnKF-KNN method in improving the accuracy of epidemic predictions. The hybrid approach significantly outperforms traditional models in forecasting epidemic dynamics. Compared to single-method approaches such as Kalman Filtering (KF) and Ensemble Kalman Filtering (EnKF), the hybrid EnKF-KNN method exhibits superior precision and robustness. When compared to other hybrid methods, such as the combination of 4DVAR and EnKF, the EnKF-KNN method shows similar performance but with enhanced computational efficiency, which is especially critical in dealing with the complex and rapidly changing transmission dynamics observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike traditional models that often rely on static assumptions or simplified transmission hypotheses, the hybrid method leverages real-time adjustments and pattern recognition to more accurately capture the dynamic features of epidemic spread. This makes it a valuable tool for informing public health strategies in dynamic environments and highlights its substantial potential for application in the field of infectious disease forecasting.

In future research, we plan to integrate recent data on population mobility and social behavior to further enhance the accuracy of real-time predictions. Mobility data provides more precise spatiotemporal information, enabling the model to capture more dynamic transmission patterns, thereby improving the timeliness and accuracy of forecasts. Additionally, we aim to apply the hybrid data assimilation method to a variety of epidemic models to improve forecasting performance across different objectives. For instance, in addition to the existing SEAIQR model, we plan to extend it to models such as the SQIR model18and the modified SEIR pandemic fractional-order model19, with the goal of addressing the unique transmission characteristics of different types of epidemics using diverse model structures.

With the increasing availability of multi-source observational data, we will also explore new numerical methods to optimize the coupling of different types of observational data20,21. By more effectively integrating data from multiple sources, we aim to enhance data utilization and generalizability, thus providing more reliable support for epidemic forecasting and control in various contexts. This approach not only improves the predictive accuracy of the models but also strengthens their adaptability to different regions and transmission patterns, further expanding their potential for real-world applications.

Conclusion

The hybrid data assimilation approach that combines real-time EnKF with KNN, as proposed in this study, demonstrates substantial effectiveness in refining data within infectious disease models, thereby enhancing their predictive accuracy to a notable extent. On the basis of these findings, the study provides a statistical projection indicating that the hybrid method is particularly effective in the context of epidemic control strategies tailored to specific regional characteristics, with its efficacy showing a positive correlation to the degree of regional specificity. Nevertheless, the method is not without its limitations, particularly in the precise selection of time-varying parameters. Moreover, there exists considerable potential for further investigation into the methods adaptability across various regions or infectious diseases, especially in scenarios where initial parameter fluctuations are present. It is anticipated that this study will serve as a catalyst for further scholarly research in this area.

Data availability

The dataset generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

N, Imai., I, Dorigatti., A, Cori. et al. Report 2: Estimating the potential total number of novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) cases in wuhan city, china. Tech. Rep., Imperial College London (2020).

Q, Li., X, Guan., P, Wu. et al. Early transmission dynamics in wuhan, china, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine 382, 1199–1207 (2020).

Wu, J. T., Leung, K. & Leung, G. M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-ncov outbreak originating in wuhan, china: a modelling study. The Lancet 395, 689–697 (2020).

Nadler, P. et al. An epidemiological modelling approach for covid-19 via data assimilation. European Journal of Epidemiology 35, 749–761 (2020).

Anderson, R. M. Discussion: the kermack-mckendrick epidemic threshold theorem. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 53, 1–32 (1991).

Rhodes, C. J. & Hollingsworth, T. D. Variational data assimilation with epidemic models. Journal of Theoretical Biology 258, 591–602 (2009).

Bettencourt, L. M. A., Ribeiro, R. M., Chowell, G. et al. Zaimis, E. (ed.) Towards real time epidemiology: data assimilation, modeling and anomaly detection of health surveillance data streams. (ed.Zaimis, E.) Neuromuscular junction. Handbook of experimental pharmacology, Vol. 42, 79–90 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Heidelberg, 2007).

Papageorgiou, V. E. & Tsaklidis, G. An improved epidemiological-unscented kalman filter (hybrid seihcrdv-ukf) model for the prediction of covid-19. application on real-time data. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 166, 112914 (2023).

Papadakis, N. et al. Data assimilation with the weighted ensemble kalman filter. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 62, 673–697 (2010).

Lal, R., Huang, W. & Li, Z. An application of the ensemble kalman filter in epidemiological modelling. PLOS ONE 16 (2021).

Ma, Y., Xu, S., Luo, Y. et al. Model-based analysis of the incidence trends and transmission dynamics of covid-19 associated with the omicron variant in representative cities in china. BMC Public Health 23 (2023).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Evaluating the demand for nucleic acid testing in different scenarios of covid-19 transmission: A simulation study. Infectious Diseases and Therapy 13, 813–826 (2024).

Yifei, M. et al. Prediction of covid-19 epidemic trend in xi’an based on seaiqr model and dropout-lstm model. Chinese Journal of Health Statistics 41, 207–212 (2024) ((in Chinese)).

Yi, C., Aihong, W., Bo, Y. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of covid-19 infections among close contacts in ningbo. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology (2020). (in Chinese).

Jing, Z., Luping, Y., Yan, Z. et al. Analysis of close contacts with covid-19 in sichuan province. Chinese Journal of Public Health (2020). (in Chinese).

Yu, M. et al. Analysis of risk factors for covid-19 infection among close contacts in guangzhou. Chinese Journal of Public Health 36, 507–511 (2020) ((in Chinese)).

Ma, Y. et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 epidemic prediction in shanghai under the “dynamic zero-covid policy’’ using time-dependent seaiqr model. Journal of Biosafety and Biosecurity 4, 105–113 (2022).

Shah, K., Abdeljawad, T. & Din, R. U. To study the transmission dynamic of sars-cov-2 using nonlinear saturated incidence rate. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 604, 127915 (2022).

Arfan, M. et al. On nonlinear dynamics of covid-19 disease model corresponding to nonsingular fractional order derivative. Medical Biological Engineering Computing 60, 3169–3185 (2022).

Riaz, M. et al. A comprehensive analysis of covid-19 nonlinear mathematical model by incorporating the environment and social distancing. Scientific Reports 14, 12238 (2024).

Shah, K., Sarwar, M. & Abdeljawad, T. On mathematical model of infectious disease by using fractals fractional analysis. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems-S 0–0 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Yang, L. A hybrid data assimilation method based on real-time Ensemble Kalman filtering and KNN for COVID-19 prediction. Sci Rep 15, 2454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85593-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85593-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Artificial intelligence driven platform for rapid catalytic performance assessment of nanozymes

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

AI-driven techniques for detection and mitigation of SARS-CoV-2 spread: a review, taxonomy, and trends

Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2025)