Abstract

Lymphedema is characterized by persistent swelling due to impaired lymphatic function and presents significant challenges in both research and clinical settings. Traditional contact-based measurement techniques such as paw thickness and circumferential measurements using calipers or silk thread are useful but limited by observer variability and measurement accuracy. Non-contact methods, including various imaging techniques, offer improvements but often at higher cost and complexity. In this study, we address the need for a more reliable, cost-effective, and non-invasive method for assessing lymphedema in mouse models. Here we show that 3D scanning technology can enhance the measurement of lymphedema in a mouse hindlimb model. Our results indicate that 3D scanners provide more consistent measurements with lower variability compared with conventional methods and without the need for direct contact, which could potentially alter the measurement outcomes. The findings of this study suggest that 3D scanning could replace traditional methods, offering a more standardized and less subjective tool for lymphedema research in the near future. This technology would not only improve upon conventional methods but also extend the capabilities for detailed anatomical analyses in small animal models, which could have implications for other areas of biomedical research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Secondary lymphedema is a condition marked by persistent swelling and inflammation due to impaired lymphatic function resulting from trauma, surgery, parasitic infection, radiation therapy, and so on1,2,3. This condition often leads to physical disfigurement and hinders the natural process of wound healing4. Because an effective cure has yet to be discovered, it is imperative to delve into the underlying mechanisms of this disease. Research involving animal models is indispensable and provides a foundational platform for biomedical research aimed at uncovering new insights and treatments5.

The mouse is a cost-effective and manageable animal model utilized extensively in lymphedema research6,7. Its diminutive size presents both challenges and opportunities in medical modeling, and proficient microsurgical skills are essential, given the intricacy of the structures involved. A critical aspect of evaluating the severity and progression of lymphedema is the gross assessment of affected areas, which are often so minute that accurate measurement becomes a delicate task8. Common sites selected for inducing lymphedema include the forelimb, hindlimb, and tail, for which the small scale requires precise and sensitive assessment techniques5. These techniques are broadly classified into contact and non-contact methods. Contact methods, such as caliper-assessed paw thickness and limb circumference measurement, are straightforward but have drawbacks such as measurer dependency and the risk of altering results due to the deformability of swollen limbs9. In contrast, non-contact methods, predominantly computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), provide highly precise surface anatomy and measurer-independence but both have the disadvantage of higher cost while CT additionally involves radiation exposure10.

Three-dimensional (3D) body imaging techniques were developed for the clothing and apparel industries11 but have recently become widely used in the medical field. Commercially available 3D body scanners are used to monitor obesity, while 3D face scanners aid in facial cosmetic planning and maxillofacial surgery and can even capture motion and expressions12. Using these techniques, lymphedema assessments are now being performed in the clinical setting, such as for parasite-induced lymphedema or post-operative lymphedema13,14,15. These examples indicate that 3D scanning is now recognized as a valuable tool for precise and reproducible measurements in lymphedema management.

Our study builds on this well-established clinical concept, bringing it back to the laboratory setting to evaluate lymphedema in experimental models using a recently released consumer-grade 3D scanner.

Materials and methods

Ethical considerations

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Japanese Act on Welfare and Management of Animals. Our animal use protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hokkaido University (Approval No. 23–0133). Additionally, we confirm that all methods are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines, which supports the transparent and comprehensive reporting of research findings.

Lymphedema model

Eight-week-old male C57BL/6 N mice (SLC, Tokyo, Japan) were acclimatized in a controlled environment at 24 °C with a 12-h light/dark cycle and were given free access to food and water. They underwent a 1-week adaptation period before the commencement of the study. Our team developed the murine hindlimb lymphedema model with reference to an established procedure16. Briefly, the procedure involved a circumferential incision in the left inguinal region, ligation of the efferent and afferent lymphatic vessels, and removal of the popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes along with the adjacent fat tissue. A silicone splint (Tigers Polymer, Osaka, Japan) was placed into the wound and subsequently secured to both the skin and the underlying muscle, using 6 − 0 nylon sutures.

Assessment of limb circumference (silk method)

The circumferential measurement technique for the hindlimb, as reported by Yoshida et al., involves positioning a 5 − 0 moistened silk thread 5 mm above the heel (point A), ensuring that it lies flat against the skin without any gaps under a surgical microscope (S100/OPMI® pico; Carl Zeiss Surgical GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany) (Fig. 1a). After tying, the thread is cut and affixed to tape (Transpore white; 3 M, Maplewood, MN) (Fig. 1b) and then meticulously measured using a vernier micrometer (Digital Caliper Mini 2 100 mm; Shinwa Rules Co., Ltd., Niigata, Japan) for precise accuracy17 (Fig. 1c).

Assessment of paw thickness (caliper method)

The paw thickness measurement is performed 9 mm distal to the heel (point B), using a vernier micrometer, with the measurements observed using a surgical microscope8.

3D scanning procedure (scanner method)

3D scanning was performed using a consumer-grade scanner (Revopoint MINI; Revopoint 3D Technologies Inc., Shenzhen, China), which was chosen for its high accuracy (accuracy ± 0.02 mm), as outlined in the manufacturer’s specifications. To ensure consistency across scans, a custom enclosure was constructed specifically for this study, using a 3D printer (Fig. 2a). This enclosure allowed for the stable placement of the scanner and secure positioning of the animal. The mouse was placed on a specially designed concave plate equipped with hangers to facilitate the positioning of the hindlimb. This plate was mounted on a rotating arm within the enclosure and set to rotate at a consistent speed of 3 to 4 revolutions per minute in order to obtain a complete 360-degree scan. Chalk for rock climbers (Setouchi Magnesio Climbing; Sanyou Clay Industry Co., Ltd., Okayama, Japan) was applied to the skin surface of the mouse as necessary to increase the brightness and enhance the capture sensitivity of the scanner. The resulting point cloud data were then carefully reviewed by each rater to identify and document any instances of incomplete data capture. If the gaps were determined to significantly distort the shape or contour of the object, corrective measures were implemented. These measures involved either re-scanning the object or acquiring additional data for the missing regions to ensure that the final point cloud data accurately reflected the true geometry of the object.

3D scanning workflow, (a) 3D scanner enclosure system for mouse lower limb lymphedema assessment, White arrowhead: motor, Gray arrowhead: Control for adjusting revolutions per minute, Black arrow: 3D scanner, White arrow: Sockets for the 3D scanner, located around the circle at 0 degrees, − 30 degrees, − 45 degrees, and − 60 degrees (worm’s eye view). Gray arrow: Mouse set on a plate hanging from the motor with a concave groove for the trunk of the mouse, which is 13 cm from the 3D scanner, Scale bar: 15 cm, (b) Collection of raw data (point cloud). Point clouds of both sides of the hindlimb were successfully collected. Note that the point clouds on the splint, which are an obvious landmark for volume assessment, and the distal toe with the nail are missing. (c) Measurement of a 3D object in virtual space using 3D Slicer, The length, area, and volume of the object are easily assessed using the software.

Mesh model generation and parameter measurement

Raw data were converted into mesh models using Revo Scan 5 (ver. 5.0; Revopoint 3D Technologies Inc.), the proprietary software of the scanner manufacturer (Fig. 2b). To streamline and simplify the processing workflow, we utilized the “one-click edit” feature of the software, which automates the key point cloud processing steps, including isolation, overlap detection, smoothing, and simplification. Next, we routinely executed the “isolation” and “fill holes” operations, employing the “plane” method to render the object as a solid, continuous mesh. After the STL file was generated by Revo Scan 5, the mesh model was imported into 3D Slicer (ver. 5.6.1; The Slicer Community) with a defined spacing of 0.04 mm18,19. Measurement parameters, mirroring conventional techniques, were manually defined using the markup tools available in 3D Slicer. The cross-sectional area at Point A and the volume distal to the splint were calculated (Fig. 2c). Mice in the non-operated group, which lacked clear landmarks for volume assessment, were excluded from the volumetric study.

Micro-CT

CT images were acquired using the IVIS Spectrum CT imaging system (PerkinElmer, Inc., Hopkinton, MA) under isoflurane anesthesia, with the mice placed in a prone position. The scanning parameters included a voxel size of 75 μm, field of view of 6 × 6 × 3 cm, aluminum filter thickness of 440 μm, binning set at 2, and estimated radiation dose of 13.2 mGy. The acquired images were segmented using 3D Slicer, after which the parameters were consistently measured (Fig. 3). We evaluated the precision and consistency of limb measurement techniques across a cohort of 27 mice, categorized by edema severity into three distinct groups: one without edema (comprising three mice), one with severe edema observed at post-operative days (PODs) 3 to 4 (comprising three mice), and a third with moderate edema at PODs 9 to 11 (comprising three mice). To ensure a comprehensive assessment, three raters performed three evaluations each on different individuals within these groups, employing both conventional methods and the novel 3D scanning technique to measure circumference and paw thickness, as well as to assess cross-sectional area and volume. Micro-CT scans, performed once for each limb, served as the high-precision gold standard for comparison.

Rater training and time efficiency

The three raters involved in the comparative analysis, who are not listed as authors, had no prior experience with the assessment processes. For training purposes, they each performed 10 practice measurements on limbs not included in the study, using the conventional techniques. They also completed three trial scans to familiarize themselves with the scanning process. The first author demonstrated the process once and provided feedback throughout the training period to ensure consistency and accuracy. Both the measurement techniques and the scanning process were recorded on video for time analysis, which was performed on a second-by-second basis. The measurement time was defined as follows. For the silk method, the starting time was the moment the rater aligned their eyes with the microscope lens, and the endpoint was when the silk string was straightened and attached to the surgical tape. The measurement time for paw thickness began when the rater picked up the caliper and ended when the value was recorded on the chart. Scanning time commenced with the press of the start button in the application and concluded after the rater briefly checked the point cloud data for any missing parts and labeled the raw data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed to evaluate the reliability and accuracy of limb measurement techniques against the micro-CT reference standard. Employing the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) model, we assessed intrarater reliability for all measurement methods and analyzed accuracy through inter-rater comparisons with micro-CT. Additionally, the novel 3D scanning method measurements of cross-sectional area and volume were evaluated against the micro-CT reference using Bland–Altman plots and the ICC to provide insights into the agreement and consistency of these new parameters. The training effect was analyzed by linear regression in terms of time efficiency and measurement differences compared with CT. Each parameter was analyzed using linear regression. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP ver. 17 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Intrarater reliability

Table 1 displays the ICC values for intrarater reliability, illustrating the consistency with which three raters performed limb measurements over three evaluations. Measurements were taken using both the conventional methods and the novel 3D scanning technique to assess circumference, paw thickness, cross-sectional area, and volume. The reported ICC values ranged from 0.75 to 0.99, except for Rater 2’s measurement using the silk method, reflecting a spectrum of reliability from good to excellent across the different methods and parameters measured. These values not only provide insight into the precision of each method but also underscore the potential for their application in consistent data collection for lymphedema research.

Rater-specific characteristics in measurement method applications

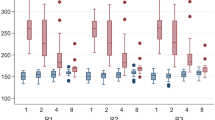

Given that measurements were performed on different individuals, we could not assess direct inter-rater reliability. However, analyzing the differences in limb measurements between the conventional and scanner methods compared with the micro-CT reference provided insights into rater-specific characteristics and their impact on measurement accuracy. Discrepancies in circumference measurements were observed. Using the silk method, Raters 1 and 2 manifested slight overestimations compared with the micro-CT standard, with mean differences of 0.51 mm and 0.45 mm, respectively. The confidence intervals ranged from 0.14 mm to 0.87 mm for Rater 1 and from 0.08 mm to 0.81 mm for Rater 2. In contrast, Rater 3’s approach resulted in an underestimation, as evidenced by a mean difference of − 0.55 mm and a confidence interval ranging from − 0.92 mm to − 0.19 mm (Fig. 4a).

Comparative analysis of measurement discrepancies across raters. (a) Silk and scanner methods compared with the micro-CT reference in terms of circumference: Boxplots compare the variability of the silk and scanner methods with the micro-CT reference across the three raters. The plots highlight the significantly lower variability of the scanner method, showcasing its superior consistency and reliability in measuring limb dimensions. This makes the scanner method a preferable choice for accurate limb assessments. (b) Caliper and scanner methods compared with the micro-CT reference in terms of paw thickness: This figure illustrates the comparison of paw thickness measurements using the caliper and scanner methods compared with the CT reference across three raters. The analysis shows that the scanner method measurements are notably closer to the CT values, as evidenced by the lower variability and tighter confidence intervals compared with the caliper method. This indicates the enhanced precision and reliability of the scanner method for paw thickness assessments, Silk: Circumference measured using the silk method. Scanner: Circumference measured using the scanner method.

CT: Circumference measured using micro-CT. X: Average.

The analysis of paw thickness measurements revealed distinct patterns between the caliper and scanner methods. With the caliper method, Rater 1 displayed a notable underestimation tendency, with a mean difference of − 0.58 mm and a confidence interval ranging from − 0.67 mm to − 0.48 mm, whereas Rater 3 showed a slight overestimation, with a mean difference of 0.18 and a confidence interval ranging from 0.08 mm to 0.27 mm. In contrast, the scanner method demonstrated heightened consistency, particularly highlighted by Rater 3’s approximately zero mean difference, which precisely mirrored the micro-CT standard with confidence intervals reflecting tighter agreement, ranging from − 0.19 mm to − 0.06 mm for Rater 1, − 0.22 mm to − 0.09 mm for Rater 2, and − 0.06 mm to 0.06 mm for Rater 3 (Fig. 4b).

Rater dependency was reduced by utilizing 3D scanners in both circumference and paw thickness assessments.

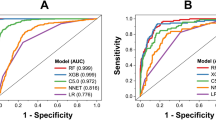

Inter-method analysis

Bland–Altman analysis revealed notable performance variations among the limb measurement techniques compared to the CT reference (Fig. 5). For circumference measurements, the silk method exhibited a mean difference of 0.14 mm and wide limits of agreement (LoAs) ranging from − 1.95 mm to 2.22 mm, indicating significant variability and reduced estimation accuracy (Fig. 5a). In contrast, the scanner method achieved a similar mean difference of 0.16 mm but with much tighter LoAs (− 0.90 mm to 1.23 mm), reflecting greater consistency and fewer deviations from the CT standard (Fig. 5b). The accuracy differences were likely influenced by postural changes required during measurement, particularly with the silk method. These results highlight the superior reliability of the scanner method over the silk method. For paw thickness measurements, the caliper method demonstrated a mean difference of − 0.18 mm, with LoAs from − 0.97 mm to 0.06 mm, indicative of a substantial underestimation and high variability (Fig. 6a). By comparison, the scanner method showed a smaller mean difference of − 0.09 mm and narrower LoA range (− 0.46 mm to 0.26 mm), suggesting reduced variability and a subtler bias relative to the CT standard (Fig. 6b). Although both methods tended to underestimate measurements compared to CT, the scanner method consistently demonstrated lower variability and smaller bias for both circumference and paw thickness.

Assessment of agreement for circumference measurements, (a) Silk method compared with the CT reference: The Bland–Altman plot visualizes the agreement between circumference measurements obtained using the silk method and those from the CT reference. The plot displays the mean difference and the limits of agreement, illustrating the variability of the silk method compared with the CT standard. This analysis provides a detailed view of the accuracy of the method in capturing circumference measurements. (b) Scanner method compared with the CT reference: The Bland–Altman plot illustrates the consistency of circumference measurements between the scanner method and the CT reference and shows the mean difference and the narrower limits of agreement, highlighting the more consistent performance of the scanner method relative to the CT standard. This plot emphasizes the improved precision of the method across various measurements. Silk: Circumference measured using the silk method.

Scanner: Circumference measured using the scanner method.

CT: Circumference measured using micro-CT.

Assessment of agreement for paw thickness measurements, (a) Caliper method compared with the CT reference: The Bland–Altman plot contrasts the paw thickness measurements obtained with the caliper method against those from the CT reference. This plot reveals a consistent trend of underestimation and illustrates the broad limits of agreement, highlighting significant variability in these measurements. This analysis underscores the range of consistency within the caliper method measurements. (b) Scanner method compared with the CT reference: The Bland–Altman plot compares paw thickness measurements taken by the scanner method with the CT reference. This plot shows a lesser degree of underestimation and features narrower limits of agreement, suggesting greater consistency and enhanced reliability in the measurements provided by the scanner method. Caliper: Circumference measured using the silk method.

Scanner: Circumference measured using the scanner method.

CT: Circumference measured using micro-CT.

The results highlight differences in the performance of measurement methods across edema severities (Tables 2 and 3). The silk method showed smaller absolute bias under no edema and severe edema conditions, suggesting an occasional advantage in accuracy. However, it exhibited higher bias in moderate edema, along with greater variability reflected in larger standard deviations and wider LoAs, particularly in severe cases, leading to reduced repeatability and precision. The caliper method showed higher absolute bias compared to the scanner method, with increased bias under severe edema. Additionally, the caliper method demonstrated larger standard deviations and wider LoAs, indicating reduced repeatability and precision as edema severity increased. In contrast, the scanner method displayed consistently lower standard deviations and narrower LoAs, indicating repeatability across all severities. While not always achieving the lowest bias, its overall performance was more consistent and robust, minimizing variability and operator dependency and suggesting superior reliability, making it a more practical option for edema assessment.

Cross-sectional area and hindlimb volume for new parameters

Bland–Altman analysis of cross-sectional area measurements using the novel method against CT scans showed a mean bias of 0.55, suggesting a slight overestimation. The variability was notable, with a standard deviation of 1.03 and LoAs ranging from − 1.48 to 2.57. However, the novel method maintained high reliability, as evidenced by an ICC of 0.977, indicating excellent consistency despite the presence of systematic bias and wide variability (Fig. 7a). The analysis of hindlimb volume using the novel method compared with the CT scan revealed a significant underestimation, with a mean bias of − 15.85 and high variability, as shown by a standard deviation of 47.58. The LoAs ranged broadly from − 109.11 to 77.40, highlighting the potential of the method for both underestimation and overestimation. Nevertheless, the method demonstrated very high reliability, with an ICC of 0.982, suggesting consistent reproducibility despite its tendency to underestimate volume. Calibration adjustments are recommended to improve accuracy while preserving reliability (Fig. 7b).

New parameters in lymphedema assessment, (a) Cross-sectional area compared with the CT reference: The Bland–Altman plot contrasts the measurements of cross-sectional area against the CT reference, revealing a trend of systematic overestimation. Despite this overestimation, the limits of agreement of the plot show significant variability, which points to underestimation in some cases. This indicates a range of consistency in the scanner method measurements. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for this assessment is 0.977, reflecting high reliability. (b) Hindlimb volume compared with the CT reference: The Bland–Altman plot contrasts hindlimb volume measurements against the CT reference, also revealing a trend of systematic overestimation. Similarly, the limits of agreement show significant variability, suggesting underestimation at times, which indicates variability in the scanner method measurements. The ICC for this assessment is 0.984, demonstrating very high reliability.

Time and training effects

The time taken to perform measurements varied significantly among methods (Figure S1). For the silk method, the average time was 68 s, with a minimum of 32 s and a maximum of 146 s. The caliper method was quicker, averaging 18 s, with a range from 8 to 42 s. The scanner method’s times ranged from 27 to 83 s, with an average of 45 s.

The training effect for each rater and method was analyzed based on two aspects: the time required for measurement and the absolute difference from the true value (Table 4).

In the time analysis, although not all raters showed statistical significance, the silk method demonstrated a trend of reduced measurement time across the trials. All raters showed a consistent trend of approximately 1 s per trial, which may indicate the inherent difficulty of this method among three methods. For the caliper method, the results were more variable, but the training effect was minimal, with a time reduction of less than 1 s per trial, suggesting it is the easiest method to learn. Similarly, for the scanner method, the slope was also less than 1 s per trial, indicating that performance reached a plateau starting from the first trial (Figure S2). In terms of accuracy, the conventional technique revealed a decline in accuracy for some raters as the trial number increased, highlighting the challenge of maintaining precision over multiple trials. Conversely, the scanner method exhibited relatively stable performance from the first across trials for most raters. However, for Rater 2, the first 10 trials showed relatively high variability, but thereafter, accuracy stabilized, consistently falling well within the limits of agreement throughout the remaining evaluations. Overall, we conclude that the training effect is minimal across all methods, with no substantial improvements in time or accuracy observed over repeated trials, suggesting that all methods are relatively easy to perform.

Discussion

The methods used to assess mouse hindlimb lymphedema can be categorized into contact and non-contact techniques depending on whether or not there is direct contact with the object. Conventional techniques are contact methods, while non-contact methods involve the use of planimetry and plethysmometers8,20.

Contact methods are less costly and do not require specific instruments except for a microscope. However, these methods have obvious limitations in terms of observer dependency as well as sample bias, given that these parameters reflect only one landmark of an entire limb. As shown in Table 1; Fig. 4, these issues not only highlight the individual measurement tendencies and habitual techniques of each rater but also illustrate the distinct reliability and unique tendencies of their measuring techniques. These observations confirm that the methods employed are dependent on the rater’s skill and consistency, emphasizing their inherent rater dependency. Procedural factors include the risk of measuring in an oblique setting and the tightness of the knot due to improper stringing technique and inconsistent application of caliper pressure. To mitigate variability, it is necessary to perform repeated measurements, conventionally in triplicate, to achieve a reliable estimate21. Object-related factors include the posture of the subject and the softness of the tissue, as well as heterogeneous swelling patterns that may present as localized contractions or a cone-shaped swelling rather than uniform swelling. In addition, when measuring at the level of the ankle, there are grooves, medially and laterally, between the Achilles tendon and the lateral and medial malleolus22. A measurement of circumference does not reflect these grooves.

Non-contact methods are considered more ideal for lymphedema evaluation because they assess the entire limb. Photography-based planimetry can be affected by the photo angle, the posture of the mouse, and the landmark setting. Volume assessment techniques such as plethysmometry in tiny objects have limitations, including difficulty in landmark setting and sensitivity to even tiny amounts of water that adhered to the object during the previous measurement, despite being the most ideal parameter for assessing lymphedema20. Radiological evaluations can overcome the above-mentioned limitations, but the cost and radiation exposure are the main issues.

3D scanners can be roughly categorized into contact and non-contact types, similar to conventional measurement techniques. The non-contact scanners include time-of-flight scanners, which calculate the distance to various points on an object by measuring the time it takes for a light source, such as a laser, to hit the object and reflect back to the sensor23. Structured light scanners project a pattern onto the object and use multiple optical cameras to detect the deformation of this pattern24. The photogrammetry technique involves taking photographs from multiple angles around the object and merging these images to construct a 3D model25.

3D scanners are less rater-dependent and offer higher repeatability than conventional techniques. Conventional methods are more prone to rater dependency, which may be influenced by factors such as the rater’s level of professional training and practical experience, personal habits such as adjustments or the tension applied to silk strings or caliper pressure, and a predisposition to bias from prior measurements. These aspects are reflected in Fig. 4, which highlights the variability among raters and the influence of their individual characteristics on measurement consistency. The intrarater reliability, as evaluated through ICC ranges, also varied, indicating the rater dependency of the conventional techniques (Table 1). This variability further supports the advantages of scanner methods in minimizing rater dependency and achieving more consistent measurements across operators. As shown in Table 4, these methods require minimal training, making them accessible to a wider range of operators with varying levels of expertise. Additionally, scanner methods appear to be relatively unaffected by the severity of edema (Tables 2 and 3). In contrast, conventional methods exhibit increasing variability as edema severity rises, likely due to the difficulty in maintaining consistent string tension or caliper pressure when measuring soft, swollen tissue. This limitation underscores the challenges of conventional techniques in ensuring accuracy under varying edema conditions.

As shown in Table 4, scanner methods require minimal training, making them accessible to a wider range of operators with varying levels of expertise. Additionally, they do not require microscopic techniques and allow multiple parameters to be recorded in a single scan. Consequently, they are considered less time-consuming and require less effort. As demonstrated in Figs. 3D and 7 scanners show potential in providing precise measurements of the volume and cross-sectional area. Their most significant advantage is the ability to accurately assess limb volume, which is deemed the ideal parameter for lymphedema evaluation. This is achieved without radiation exposure and at a lower cost than traditional methods such as plethysmometers and micro-CT.

Despite these benefits, 3D scanners have several limitations. Consumer-level 3D scanners, while increasingly accessible, cost more than USD 1,000, a substantial increase compared with the nominal expenses of conventional circumference measurement methods that only require a silk string and caliper. In addition, the transformation of raw scan data into functional 3D models proved to be computationally demanding. With a consumer-grade laptop (M2 MacBook Air; Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA), the conversion times ranged from 11 s to 59 s. Moreover, each 3D model of a single leg required approximately 10 megabytes of storage space. Proficiency in handling the scanning software was found to be pivotal for the efficacy of the operation. Compared with radiological evaluation, 3D scanners do not contain the internal structure of the reference needed to set a standardized or repeatable landmark, and thus a highly precise setting of landmarks for volumetric assessment is required. Despite the highly controlled environment, scan failures, although rare, were observed. We have no precise definition of scan failure, so the total failure rate cannot be assessed. The reasons for failure varied and can be categorized into the following three types. The first reason was surface brightness, as described in the manufacturer’s instruction manual26. In this study, surface brightness was low due to hyperemia and hair follicles. These issues are easily overcome by applying additional powder to the surface. The second reason was a posture change resulting from shallow anesthesia. Shivering and bucking, which do not affect the angle of major joints, do not influence the scan results but the scan process fails when the mice flex their knees and hips. These drawbacks can be overcome by deepening the anesthesia. The third reason, which is unpredictable, was object recognition failure. Despite proper setting of an object at the proper distance, the scanner sometimes fails to recognize the object. This seems to be the result of instability that is sometimes typical of first-generation products. Although unpredictable, these failures were successfully addressed by simply restarting the scanning process in the software or repositioning the object. The study design also presents limitations regarding inter-rater reliability: each rater measured different individuals, thereby precluding direct assessment of inter-rater reliability. Additionally, this study represents a single time point analysis and does not evaluate changes in parameters over time within the same individuals.

In clinical settings, lymphedema severity is typically assessed using methods such as water displacement, circumference measurements, ultrasound, and other radiological modalities, which are similarly utilized in research environments. Studies by Yahathugoda et al. and White et al. have reported on the clinical application of 3D scanning, highlighting benefits and limitations that align closely with those observed in this research13,15. The major advantages of 3D scanning technology include its high accuracy with repeatability, non-invasiveness, independence from lymphedema severity, and a hygienic nature, as it eliminates the need for direct contact with the patient’s skin. The technology also allows the extraction of multiple parameters from a single scan, requires minimal training, is less dependent on the operator, and ensures consistent results across different evaluators. The limitations of 3D scanning technology include the cost of the scanner and the requirement for additional data processing time. However, these challenges are being progressively addressed through technical advancements, such as integrated “in-device” processing, improved affordability, and the seamless integration of software with medical record systems. As these developments continue, this technology is likely to see broader applications in the near future.

Conclusion

3D scanning technology offers benefits such as high accuracy, superior repeatability, reduced rater dependency, and the ability to record multiple parameters in a single scan. Additionally, these devices are non-invasive, require minimal training, and avoid radiation exposure, making them safer and more accessible than traditional techniques. Their ability to deliver detailed and consistent volumetric measurements across varying edema severities underscores their potential as a reliable and innovative tool in lymphedema research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Grada, A. A., Phillips, T. J. & Lymphedema Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 77, 1009–1020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.03.022 (2017).

Allam, O. et al. The impact of radiation on lymphedema: a review of the literature. Gland Surg. 9, 596–602. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2020.03.20 (2020).

Lammie, P. J., Cuenco, K. T. & Punkosdy, G. A. The pathogenesis of filarial lymphedema: is it the worm or is it the host? Ann N Y Acad Sci 979, 131–142; discussion 188–196 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04874.x

Mallon, E. C. & Ryan, T. J. Lymphedema and wound healing. Clin. Dermatol. 12, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0738-081x(94)90260-7 (1994).

Hsu, J. F., Yu, R. P., Stanton, E. W., Wang, J. & Wong, A. K. Current advancements in animal models of Postsurgical Lymphedema: a systematic review. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle). 11, 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1089/wound.2021.0033 (2022).

Frueh, F. S. et al. Animal models in surgical lymphedema research–a systematic review. J. Surg. Res. 200, 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.07.005 (2016).

Bucan, A., Frendo, M., Ngo, M. T., Sorensen, J. A. & Holmich, L. R. Surgical lymphedema models in the mice hindlimb-A systematic review and quality assessment. Microsurgery 44, e31088. https://doi.org/10.1002/micr.31088 (2024).

Frueh, F. S. et al. High-resolution 3D volumetry versus conventional measuring techniques for the assessment of experimental lymphedema in the mouse hindlimb. Sci. Rep. 6, 34673. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep34673 (2016).

Shejawal, N., Menon, S. & Shailajan, S. A simple, sensitive and accurate method for rat paw volume measurement and its expediency in preclinical animal studies. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 33, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0960327113482594 (2014).

Duce, S. et al. Micro-magnetic resonance imaging and embryological analysis of wild-type and pma mutant mice with clubfoot. J. Anat. 216, 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01163.x (2010).

Bindahman, S., Zakaria, N. & Zakaria, N. in Proceedings Title: International Conference on Cyber Security, Cyber Warfare and Digital Forensic (CyberSec). 150–154. (2012).

Amornvit, P. & Sanohkan, S. The Accuracy of Digital Face Scans obtained from 3D scanners: an in Vitro Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 16 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16245061 (2019).

Yahathugoda, C. et al. Use of a Novel Portable three-dimensional imaging system to measure limb volume and circumference in patients with Filarial Lymphedema. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 97, 1836–1842. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0504 (2017).

Vitali, A., Regazzoni, D., Rizzi, C. & Molinero, G. in Design Tools and Methods in Industrial Engineering Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering Ch. Chapter 16, 177–188 (2020).

White, B. N. et al. An infrared 3D scanning device as a novel limb volume measurement tool in breast cancer patients. World J. Surg. Oncol. 18, 278. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-020-02043-y (2020).

Iwasaki, D. et al. Establishment of an acquired lymphedema model in the mouse hindlimb: technical refinement and molecular characteristics. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 139, 67e–78e. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002887 (2017).

Yoshida, S. et al. Adipose-derived stem cell transplantation for therapeutic lymphangiogenesis in a mouse secondary lymphedema model. Regen Med. 10, 549–562. https://doi.org/10.2217/rme.15.24 (2015).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3D slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001 (2012).

Velazquez, E. R. et al. Volumetric CT-based segmentation of NSCLC using 3D-Slicer. Sci. Rep. 3, 3529. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep03529 (2013).

Bucan, A. et al. Microcomputed tomography versus plethysmometer and electronic caliper in the measurements of lymphedema in the hindlimb of mice. Sci. Rep. 12, 12267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16311-2 (2022).

Institution, B. S. Accuracy (trueness and precision) of measurement methods and results: basic methods for the determination of repeatability and reproducibility of a standard measurement method. ISO 5725 part 2 (1994).

Charles, J. P., Cappellari, O., Spence, A. J., Hutchinson, J. R. & Wells, D. J. Musculoskeletal geometry, muscle Architecture and Functional specialisations of the mouse Hindlimb. PLoS One. 11, e0147669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147669 (2016).

Cui, Y., Schuon, S., Chan, D., Thrun, S. & Theobalt, C. in 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 1173–1180.

Kantaros, A., Ganetsos, T. & Petrescu, F. I. T. Three-Dimensional Printing and 3D scanning: Emerging technologies Exhibiting High potential in the field of Cultural Heritage. Appl. Sci. 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/app13084777 (2023).

Galantucci, L. M., Lavecchia, F., Percoco, G. & Raspatelli, S. New method to calibrate and validate a high-resolution 3D scanner, based on photogrammetry. Precis. Eng. 38, 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.precisioneng.2013.10.002 (2014).

Revopoint 3D Technologies Inc. User Manual for Revopoint MINI 3D Scanner, (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Emi Funayama, Hiroko Ishii, Masahiro Hojo and Riku Ishii for their valuable advice and cooperation throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. collected the data and wrote the manuscript.R.I., T. M., Y.O. and S.N. aided to collect the data.Y. I. and K.F. conducted statistical analysis.K. I., Y.Y. and T. M supervised the throughout research plan. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, D., Ito, R., Ishikawa, K. et al. 3D scanner’s potential as a novel tool for lymphedema measurement in mouse hindlimb models. Sci Rep 15, 3747 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85637-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85637-4