Abstract

To investigate the failure mechanism and establish stability control methods for surrounding rock in high geo-stress roadways, this study incorporated the brittle failure characteristics of the surrounding rock mass into a unified strength criterion, developing an elastic-plastic theoretical model to represent rock damage and fracture. Using this model, analytical expressions for the damage rupture radius and stress field distribution are derived, leading to the proposal of a grading control method. The analysis of calculation examples reveals that an increase in stress, damage degree, and the brittleness coefficient of the rock mass results in the expansion of both the plastic damage and damage residual zones. Conversely, an increase in the intermediate principal stress coefficient and support resistance reduces the extent of these zones. The proposed grading control strategy includes three levels: Level I focus on preventing cracks through initial support, Level II involves reinforcing anchor injections to reduce cracks, and Level III applies local borehole pressure relief. Implementing this strategy can significantly reduce stress concentration and deformation in the surrounding rock, providing valuable insights for roadway support control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Roadway excavation, as the cornerstone of underground engineering construction and the lifeline of mine safety, inevitably disrupts the stress field, necessitating gradual adjustment to achieve a new equilibrium state1. During this adjustment, the pressure on the surrounding rock in the excavation area decreases, while axial stress becomes concentrated2. This stress state often causes the rock to exhibit brittle failure characteristics, leading to nonlinear degradation of mechanical properties such as peak strength3,4, which ultimately results in roadway surrounding rock failure. Therefore, accurately determining the extent of surrounding rock failure and developing targeted control methods are essential for ensuring the stability of the roadway surrounding rock5.

Currently, many scholars have investigated the damage range and stress field distribution of surrounding rock by considering various factors based on the Fenner and Kastner theory6,7. For instance, Jing et al.8. considered the rheological properties of rock, explored the zonal deformation and formation mechanism in deep buried high-stress soft rock roadways, and calculated the elastic-plastic solution for surrounding rock using the Mohr-Coulomb (M-C) and Drucker-Prager (D-P) strength criteria. Yao et al.9. divided the surrounding rock into residual, plastic softening, and elastic zones, analyzing the influence of parameters such as seepage and strain softening. They found that when the intermediate principal stress effect is not considered, the calculations tend to be conservative, preventing effective utilization of the surrounding rock strength. Jiang et al.10. applied elastic-plastic theory and the Mogi-Coulomb strength criterion, incorporating factors like lining support force and the intermediate principal stress coefficient to establish a mechanical solution for surrounding rock. Li et al.11. proposed a finite element analysis method that accounts for intermediate principal stress and shear dilatancy, introducing six types of interaction between surrounding rock and support along with their corresponding failure judgment theorems. Su et al.12. utilized the D-P criterion to describe the yield characteristics of roadways, calculating the impact of support structure and rock mechanics parameters on the plastic zone. They also identified the influence of the Lode parameter on surrounding rock failure. Zhu et al.13. analyzed the elastic-plastic mechanical characteristics of the roadway using the unified strength criterion and bilinear constitutive relationship, and solved the radius of the plastic zone. Dong et al.14. derived an equation involving soft rock mechanical parameters based on experimental data and established a roadway elastic-plastic equation to assess the effects of stress, support force, and excavation radius on roadway stress and deformation. Zhang et al.15. differentiated between elastic and plastic states, deriving an analytical solution for elastic-plastic coupling using the M-C and H-B criteria. Zhou et al.16. studied the impact of burial depth on the shape, radius, and stress distribution of the plastic zone based on the M-C failure criterion, also considering the effect of gravity. These studies comprehensively address various influencing factors, providing a more precise method for calculating stress distribution in roadway surrounding rock.

In response to specific conditions following surrounding rock failure, various adaptable control technologies have been proposed17,18. Kang et al.19. proposed the concept that surrounding rock control should be carried out in terms of in-channel support and reinforcing support after excavation. Xie et al.20,21 suggested a multi-level support strategy for deep wells with high stress, including primary support, auxiliary support, and filling walls, along with high-stress concentration transfer via large-diameter holes and shallow anchor support. Engineering practices have validated the effectiveness of these methods. Yu et al.22. investigated the support challenges of deep-buried large-span roadways, identifying six key points and proposing a comprehensive support and repair scheme incorporating anchor rods, anchor cables, and grouting. Zhang et al.23. introduced a step-by-step combined support technology to address the large deformation problem of soft rock surrounding rocks, prioritizing primary and secondary support for enhanced cost-effectiveness and efficiency. Li et al.24. developed an instability model based on mutation theory and energy transfer law, enabling the determination of support parameters and timing for surrounding rock control. Jiang et al.25. proposed a combined unloading and anchoring control method to address damage in high-stress roadways, significantly reducing roadway surrounding rock deformation. Wu et al.26. introduced a staged collaborative control method based on the distribution characteristics of the plastic zone and the stress distribution law of the surrounding rock. Practical applications have demonstrated its effectiveness in controlling surrounding rock stability.

Although the above studies have enriched the mechanical analysis and control strategies of roadway surrounding rock, the current surrounding rock mechanical analysis often ignores the nonlinear characteristics of brittle rock. In light of the considerations above, this study initially examines the nonlinear brittle damage characteristics of rock. To this end, the unified strength criterion and continuous damage mechanics method are employed to derive analytical expressions of the damage range and stress experienced by surrounding rock. Furthermore, the influence of surrounding rock mechanical distribution characteristics and parameters is analyzed. Finally, a grading control method for surrounding rock was proposed, and the effectiveness of the control method was verified through numerical analysis. The research findings offer significant value in both theoretical and practical applications.

Theoretical analysis of surrounding rock failure in high stress roadway

Distribution pattern of damage to the roadway surrounding rock

To prevent changes in damage angle and area due to variations in the principal stress direction within a circular roadway cross-section, a safer approach is to apply a uniformly distributed load equal to the maximum value of the original rock stress field27. The following assumptions are made: the burial depth H ≥ 20R0, the roadway is infinitely long and flat, the surrounding rock mass is isotropic, the spatial effect of the excavation surface is negligible, and external boundary conditions are parallel to the rectangular coordinate axes. The mechanical model of the surrounding rock of a circular roadway is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Damage constitutive model and unified strength criterion

The surrounding rock mass, subjected to external load, initiates internal crack development. As microscopic damage accumulates, the mechanical properties of the rock degrade. According to the nonlinear brittle damage constitutive model proposed by Zhang et al.28. , the stress-strain curve under uniaxial compression is simplified, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Ignoring the initial damage before the peak strength of the rock, the one-dimensional damage evolution equation under uniaxial compression is:

where \({D_1}\) is the damage variable of rock, \(\varepsilon\) is the strain during rock compression, \({\varepsilon _c}\) and \({\varepsilon _s}\) are the strain and constant corresponding to the peak stress respectively, i is the parameter representing the brittleness of rock. The larger the value of i, the stronger the brittleness of rock.

The surrounding rock subjected to tangential, radial, and axial loads. Assuming the volume strain of the damaged surrounding rock is zero, the constitutive relationship under uniaxial stress can be extended to the complex stress state. Accordingly, the stress-strain relationship under triaxial stress conditions is expressed as follows28:

where \({\sigma _j}\) and \({\varepsilon _j}\) are the equivalent stress and equivalent strain, respectively, which can be estimated using the following formula:

where \({\sigma _\theta }\) and \({\varepsilon _\theta }\) are the tangential stress and strain respectively; \({\sigma _r}\) and \({\varepsilon _r}\) are the radial stress and strain respectively; \({\sigma _z}\)and \({\varepsilon _z}\) are the axial stress and strain respectively.

By substituting Eq. (3) into Eq. (2), the resulting expression represents the relationship between stress and strain in all directions within the surrounding rock. The corresponding stress-strain curve is similar to the one shown in Fig. 2.

According to the corresponding relationship of damage variables, we have:

where \({D_2}\) is the damage variable under triaxial compression.

From the geometric conditions, the following expression can be derived:

The deformation continuity condition at the interface between the elastic zone and the damage zone is given by:

By integrating Eq. (5) and substituting it into Eq. (3), then combining with Eq. (6), the equivalent strain in the damaged area is expressed as:

By combining Eq. (7) with the corresponding relationship, the three-dimensional nonlinear continuous damage evolution equation is obtained as:

The unified strength criterion can be expressed in various forms. In geotechnical engineering, compressive stress is typically considered positive, while tensile stress is regarded as negative. When compressive strength is utilized as the material parameter, the principal stress expression of the unified strength criterion is:

where A represents the ratio of the uniaxial tensile strength to the uniaxial compressive strength of the rock. B is the unified strength theory parameter, reflecting the influence of the intermediate principal shear stress and normal stress on the material’s yield failure response surface. The effect of intermediate principal stress increases with increasing B values. When B equals zero, the unified strength criterion simplifies to the Mohr-Coulomb (MC) strength criterion.

In the plane strain case:

The intermediate principal stress coefficient is denoted as B1. As the material approaches the plastic state, B1 approaches 1. Substituting Eq. (10) into Eq. (9), and considering the stress state of the surrounding rock after excavation, we have \({\sigma _1}={\sigma _\theta }\), \({\sigma _2}={\sigma _z}\), \({\sigma _3}={\sigma _r}\). Thus, the new form of the unified strength criterion can be expressed as:

where \({M_1} = \frac{{2+2B-AB}}{{A\left( {2+B} \right)}}\), \({M_2}=\frac{{2A\left( {1+B} \right)}}{{A\left({2+B} \right)}}{\sigma _c}\).

Analysis of stress field of roadway surrounding rock

During roadway excavation, the original stress equilibrium state of the rock mass is disrupted, leading to varying degrees of damage in the surrounding rock, from shallow to deep layers. To better understand this process, two critical stress thresholds are introduced: P1 and P2. P1 signifies the critical stress at which the surrounding rock transitions from a completely elastic state to the onset of damage, while P2 denotes the limit stress at which the surrounding rock reaches a residual damage state. When the actual stress P0 is less than P1, the surrounding rock remains elastic and undamaged. Once P0 exceeds P1 but remains below P2, the surrounding rock enters a complex state, with some areas exhibiting plastic damage while others remain elastic. If P0 further increases and surpasses P2, the degree of damage intensifies, resulting in three distinct zones: the residual damage zone, the plastic damage zone, and the unaffected elastic zone. Notably, elastic rock generally maintains stability without additional support. Therefore, studying roadway surrounding rock stability necessitates an in-depth investigation of the mechanical behavior and damage state of the rock beyond the elastic limit.

Damage residual zone stress

When the stress reaches the elastic limit of the surrounding rock, the mechanical properties of the surrounding rock are damaged and degraded. According to the equivalence assumption of loads in damage mechanics, the effective stress is defined as:

where \(\left[ \hat \sigma \right]\)is the effective stress matrix, \(\left[ \sigma \right]\)is the nominal stress matrix, and D is the rock damage variable.

Therefore, the effective stress of the surrounding rock is:

By combining Eq. (11), the unified strength criterion function that accounts for damage can be expressed as:

If a complete damage zone occurs in the surrounding rock of the roadway, the damage variable of the rock mass is D = 1. From Eq. (14), we can derive:

Any point in the surrounding rock satisfies the equilibrium differential equation given by:

By combining Eqs. (15) and (16) along with the boundary condition \({\sigma _{\left. r \right|r=R}}={P_{\text{s}}}{\text{ }}\), we can derive the surrounding rock stress in the complete damage zone as:

From Eq. (17), it is evident that when the roadway is unsupported, i.e., \({P_s}=0\), the stress in the completely damaged zone of the surrounding rock becomes zero. This implies that the surrounding rock mass has no bearing capacity, which is inconsistent with actual roadway project conditions. Engineering practice indicates that after excavation, even with deformation and damage leading to a damaged zone, the rock mass retains a certain bearing capacity, maintaining some residual strength. To address this, we propose the concept of a damaged residual zone, analogous to the plastic residual strength zone in elastic-plastic mechanics analysis. In this zone, despite the deterioration of material mechanical properties, the rock mass still exhibits bearing capacity. The strength of the surrounding rock in the residual damage zone corresponds to the residual strength value, satisfying the following strength conditions:

where \(M_{2}^{\prime }=\frac{{2A\left( {1+B} \right)}}{{A\left( {2+B} \right)}}\sigma _{c}^{\prime }\), \(\sigma _{c}^{\prime }\) is the residual strength of rock.

By combining Eqs. (16) and (18) along with the boundary condition \({\sigma _{\left. r \right|r=R}}={P_{\text{s}}}{\text{ }}\), we can derive the surrounding rock stress in the damage residual zone as:

where \({M_3}=\frac{{M_{2}^{\prime }}}{{1 - {M_1}}}\).

Plastic damage zone stress

By combining Eqs. (8), (14), and (16), we obtain:

Integrating Eq. (20), we get:

where \({M_4}=\frac{{{M_2}}}{{1 - {M_1}}}\), \({M_5}=\frac{{{M_2}}}{{1 - 2i - {M_1}}}\), and \({K_i}\) is the integration constant.

At the interface between the residual damage zone and the plastic damage zone, the radial stress \({\sigma _{bs}}\)at \(r={r_b}\)can be derived using Eq. (19):

By combining Eqs. (14) and (16), and applying the boundary condition from Eq. (22), the stress in the plastic damage zone is obtained as:

Elastic zone stress

Boundary conditions in the elastic zone:

When \(r={r_s}\), we have:

The surrounding rock is in the limit state of the unified strength criterion, which can be calculated using Eq. (11):

According to elastic mechanics, the surrounding rock stress in the elastic zone is:

Damage residual zone radius and plastic damage zone radius

In the damage residual zone, it is assumed that the damage strength of the surrounding rock mass is uniform. Thus, the strength of the surrounding rock mass in this zone is reduced to the residual strength \(\sigma _{c}^{\prime }\), with the damage coefficient denoted as \({D_3}\), which can be expressed as:

From formula (28), we observe that when \(\sigma _{c}^{\prime }={\sigma _c}\), \({D_3}\)= 0, indicating that the surrounding rock is undamaged. Conversely, when \(\sigma _{c}^{\prime }\)= 0, \({D_3}\)=1, signifying that the surrounding rock is completely damaged. It is important to note that \(\sigma _{c}^{\prime }\) represents the residual strength, while \({\sigma _c}\)denotes the peak strength.

Substituting Eq. (28) into Eq. (8), we have:

At the boundary between the elastic zone and the plastic damage zone, the stress continuity condition provides:

By combining Eq. (27) and Eq. (23), we can get:

By combining Eq. (22), Eq. (28) to Eq. (31), we obtain:

where \({M_6}=\frac{1}{{{P_s} - {M_3}}}\), \({M_7}={M_5}\frac{{\varepsilon _{c}^{i}}}{{\varepsilon _{s}^{i}}} - {M_4}+\frac{{2{P_0} - {M_2}}}{{1+{M_1}}}\), \({M_8}=\frac{{{\varepsilon _s}}}{{{\varepsilon _c}}}{\left( {1 - \frac{{\sigma _{c}^{\prime }}}{{{\sigma _c}}}} \right)^{\frac{1}{i}}}\), \({M_9}={M_4} - {M_5}{\left( {1 - \frac{{\sigma _{c}^{\prime }}}{{{\sigma _c}}}} \right)^{\frac{1}{i}}} - {M_3}\).

Calculation examples and parameter analysis

The derived analytical solution reveals that the extent and stress within the damage residual zone and plastic damage zone in the surrounding rock are influenced by several factors, including support strength, rock properties, and intermediate principal stress. This section will analyze the effect of these factors.

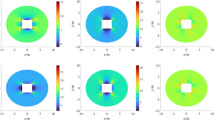

Influence of surrounding rock stress state on fracture distribution evolution

In the analysis of the stress state of surrounding rock, the original rock stress \({P_{\text{0}}}\) and the intermediate principal stress coefficient B are critical parameters. When the original rock stress \({P_{\text{0}}}\) is low, the surrounding rock typically remains intact, without deterioration or failure. However, when the original rock stress \({P_{\text{0}}}\) exceeds the elastic limit of the surrounding rock, both plastic damage and residual damage zones form. To understand the influence of original rock stress \({P_{\text{0}}}\) and intermediate principal stress coefficient B on the surrounding rock stress and failure range of the roadway, a calculation and analysis were carried out taking the circular roadway as an example. The roadway has a radius of \({R_0}\)= 3.18 m, and the compressive peak strength of the surrounding rock is \({\sigma _c}\)= 25 MPa. The rock damage coefficient is D = 95%, and the brittleness parameter is i = 5. For this analysis, support resistance is not considered, meaning \({P_S}\)= 0 MPa. Based on the findings of Zhang et al.28, when the brittleness coefficient i takes values of 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8, the corresponding ratios of \({{{\varepsilon _c}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\varepsilon _c}} {{\varepsilon _s}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\varepsilon _s}}}\)are 0.674, 0.705, 0.727, 0.744, and 0.763, respectively. Substituting these parameters into Eq. (32) allows for the calculation of the relationship between the original rock stress \({P_{\text{0}}}\), the intermediate principal stress coefficient B, and the extent of both the plastic damage zone and the damage residual zone, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The results in Fig. 3 indicate that as the original rock stress increases, both the damage residual zone and the plastic damage zone expand nonlinearly. However, the rate of increase gradually diminishes, suggesting that the influence of original rock stress on surrounding rock damage becomes less pronounced with higher stress levels. This implies that as the original rock stress continues to rise, its impact on the degree of rock damage stabilizes. Additionally, an analysis of the intermediate principal stress parameters reveals a nonlinear decreasing trend in the extent of both the residual damage zone and the plastic damage zone as these parameters increase. The rate of this decrease also gradually slows. This indicates that by adjusting the intermediate principal stress parameters, the extent of surrounding rock damage can be effectively minimized, contributing to the stabilization of the roadway structure.

Figure 4 illustrates the influence of the original rock stress and the intermediate principal stress coefficient on the stress distribution within the damaged residual zone. The results demonstrate that higher original rock stress leads to a greater peak tangential stress \({\sigma _\theta }\) in this zone. At a certain distance from the roadway, the difference between tangential and radial stresses becomes more pronounced with increasing original rock stress. This disparity may render the surrounding rock more susceptible to instability, hindering the stability of the roadway. However, as the distance from the roadway surface increases, the influence of original rock stress on the tangential and radial stress distribution diminishes. Furthermore, as the intermediate principal stress coefficient B rises from 0 to 1, the peak tangential stress in the damaged residual zone also increases, drawing closer to the surface of the surrounding rock. This pattern indicates that the intermediate principal stress coefficient significantly affects the stability of the surrounding rock. Therefore, in practical engineering, it is crucial to monitor changes in the intermediate principal stress coefficient and implement appropriate measures to ensure roadway stability.

Influence of surrounding rock properties on fracture distribution evolution

This section examines the influence of the rock damage coefficient \({D_3}\) and the brittle characteristic parameter i on the stress distribution and extent of failure in the surrounding rock of the roadway. In the analysis, the circular roadway has a radius of \({R_0}\)= 3.18, the peak strength of the surrounding rock is \({\sigma _c}\)= 25 MPa, and the original rock stress is \({P_0}\)= 40 MPa. The intermediate principal stress coefficient is set to B = 0.5, and support resistance is disregarded, meaning \({P_S}\)= 0 MPa. By substituting these parameters into Eq. (32), the relationship between the rock damage coefficient \({D_3}\), the brittle characteristic parameter i, the extent of the damage residual zone \({r_b}\), and the range of the plastic damage zone \({r_s}\) is derived, as shown in Fig. 5.

The results depicted in Fig. 5 illustrate the relationship between the rock damage coefficient, brittle characteristic parameters, and the extent of failure in the surrounding rock. When the brittle characteristic parameter remains constant, an increase in the damage coefficient \({D_3}\) leads to an accelerated expansion of both the damage residual zone \({r_b}\) and the plastic damage zone \({r_s}\). Notably, when \({D_3}\) exceeds 0.9, the expansion of the damage range follows an almost exponential trend. Specifically, when the brittle characteristic parameter i is 5, an increase in the damage coefficient from 0.5 to 0.9 causes the damage residual zone \({r_b}\) and the plastic damage zone \({r_s}\) to expand by 1.67 and 1.37 times, respectively. As the damage coefficient rises from 0.9 to 0.99, these zones expand by 3.18 and 2.38 times, respectively. Additionally, as the brittle characteristic parameter i increases, the failure range also expands. The residual damage zone \({r_b}\) is more sensitive to increases in the brittle characteristic parameter than the plastic damage zone \({r_s}\), though the overall influence of the brittle characteristic parameter is less significant compared to that of the damage coefficient.

The analysis of Fig. 6 reveals that both the damage coefficient \({D_3}\) and the brittle characteristic parameters i significantly influence the stress distribution within the surrounding rock. As the damage coefficient \({D_3}\) increases, the radial stress \({\sigma _r}\) at the same depth in the surrounding rock decreases, and the peak tangential stress \({\sigma _\theta }\) shifts deeper into the rock mass. However, the magnitude of the peak stress remains relatively constant. In contrast, the brittle characteristic parameters i have minimal impact on the peak stress itself. At different values of i, the stress distribution within the damaged residual zone remains consistent, but stress variations are observed in the plastic damage zone and elastic zone. In the plastic damage zone, both radial and tangential stresses decrease with increasing depth. In the elastic zone, radial stress continues to decrease, while tangential stress exhibits a slight increase. However, this increase is not substantial. Overall, the brittle characteristic parameters exert a limited influence on the stress distribution compared to the damage coefficient, especially within the plastic damage and elastic zones.

Influence of support strength on fracture distribution evolution

This section analyzes the influence of support strength on the stress distribution and failure range of the surrounding rock in a roadway. In the analysis, the circular roadway is assumed to have a radius of \({R_0}\)= 3.18 m, a peak surrounding rock strength of \({\sigma _c}\)= 25 MPa, an intermediate principal stress coefficient B = 0.5, a rock damage coefficient \({D_3}\) = 95%, and a brittle characteristic parameter i = 5. By substituting these parameters into Eq. (32), the relationship between the support strength \({P_S}\), the original rock stress \({P_0}\), the extent of the damaged residual zone, and the plastic damage zone is derived, as depicted in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 demonstrates that as the support resistance increases, the range of both the damaged residual zone and the plastic damage zone in the surrounding rock decreases progressively, although the rate of reduction slows over time. In the absence of support, the damaged residual zone and the plastic damage zone extend to 3.30 m and 4.46 m, respectively. When the support resistance reaches 1.0 MPa, the extent of these two zones is reduced by 63.26% and 54.59%, respectively. This indicates that support resistance plays a crucial role in controlling the deformation and failure of the surrounding rock in roadways, significantly limiting the extent of damage.

As depicted in Fig. 8, an increase in support resistance leads to a gradual reduction in the disparity between the damaged residual zone and the plastic damage zone. Additionally, both tangential and radial stresses near the surface of the surrounding rock increase, thereby enhancing the stability of the rock mass. Furthermore, with increased support resistance, the location of peak tangential stress shifts closer to the surface of the surrounding rock. However, the results suggest that support resistance does not significantly influence the peak value of the tangential stress. Therefore, by appropriately increasing support resistance and optimizing the stress distribution within the surrounding rock, the load-bearing capacity of the roadway’s structural system can be effectively improved.

Grading control technology of surrounding rock in high geo-stress roadway

Grading control method for the surrounding rock in roadways

From the analysis in the previous section and past studies, it is evident that the destruction process of the surrounding rock progresses through the gradual formation of a damaged residual zone, a plastic damaged zone, and an elastic zone, extending from shallow to deeper layers. In managing high-stress surrounding rock, it is vital to enhance the strength and stability of the damaged residual zone. Moreover, stress within the surrounding rock may increase sharply due to stress redistribution during mining operations. Considering the trends in influencing factors for the cracking and destruction of surrounding rock, as previously discussed, and incorporating our research on the spatiotemporal evolution of rock failure instability29, we propose a grading control method called “crack prevention, crack reduction, and pressure relief,” as illustrated in Fig. 9.

The Level I control strategy is predicated on preventing crack propagation through the timely implementation of support measures, with the objective of arresting further deterioration of the damaged residual and plastic damage zones. Post-excavation, the fractured residual damage zone tends to extend deeper into the surrounding rock. Consequently, the immediate deployment of anchor mesh and cable beam support systems is crucial to delay the onset of nonlinear acceleration in rock damage and inhibit the rapid expansion of the damaged residual zone. High preload anchor cables, steel belts, and steel beams are utilized to restore radial stress within the anchoring area, thereby augmenting the ultimate bearing capacity of the surrounding rock.

The Level II control strategy emphasizes the reduction of cracks through the reinforcement of the rock mass via anchor injection, with the aim of modifying the mechanical properties of the damaged residual zone. Stress concentration induced by mining activities exacerbates cracking in the surrounding rock, diminishing its cohesion and frictional resistance. This intensifies tensile and shear forces on the anchors and cables, potentially leading to the failure of anchoring systems. Following the achievement of stress equilibrium through Level I control, if rock deterioration persists, it becomes imperative to increase confining pressure to enhance the strength of the surrounding rock within the damaged residual zone.

Level III control is intended to alleviate pressure through localized drilling, with the primary aim of preventing further stress concentration across the three zones: elastic, plastic damage, and residual damage. By modifying the stress environment, the stability of the surrounding rock can be preserved. After the implementation of Level I and II controls, the stiffness of the surrounding rock increases, thereby limiting deformation and storing substantial elastic strain energy. Pressure relief holes are subsequently drilled to accommodate the expansion of the surrounding rock, permitting controlled deformation. This process releases a portion of the stored energy, thereby reducing concentrated stress impacts on support structures, ultimately ensuring the stability of the surrounding rock.

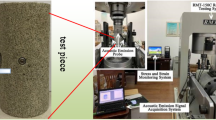

Numerical scheme for effectiveness analysis of surrounding rock grading control

According to Eq. (9), when the parameter B associated with the intermediate principal stress is zero, the model simplifies to the Mohr-Coulomb (M-C) criterion. As discussed in Sect. 3.1, the radius of the plastic damage zone increases as this parameter decreases. Therefore, in numerical simulations, the M-C criterion is employed as a conservative failure criterion to elucidate the stress and deformation characteristics of the surrounding rock following roadway excavation .

To validate the effectiveness of the grading control method, a FLAC3D numerical model was developed to compare and analyze the stress and deformation distribution of the surrounding rock under various scenarios. In the simulations, an initial stress field of 16.2 MPa was applied. Upon reaching equilibrium, roadway excavation and support control were executed, followed by an increase in stress to 32.4 MPa (representing twice the stress concentration state) to continue the analysis.

The PRU grading stability control method comprises three levels: Level I (anchor rods and anchor cables), Level II (extended anchor cables with grouting), and Level III (drilling for pressure relief). Four simulation scenarios were designed: Scheme 1 involves no support; Scheme 2 includes no support with Level I control; Scheme 3 incorporates no support with Level I and Level II controls; Scheme 4 integrates no support with Level I, Level II, and Level III controls. To assess the grading control method’s effectiveness, an equivalent circular radius of 3.18 m was selected, reflecting the conditions of a mine in Shaanxi, China. The physical parameters for the numerical simulation were validated using laboratory-obtained coal parameters: density of 1310 kg/m3, bulk modulus of 1.521 GPa, shear modulus of 1.415 GPa, tensile strength of 0.8 MPa, cohesion of 1.26 MPa, and an internal friction angle of 32º. Anchor rods were spaced at 800 × 800 mm, while anchor cables were spaced at 1600 × 1600 mm, with full-length anchoring for grouted anchor cables. The anchor rod length was 2.4 m, the anchor cable length was 6.2 m, and the extended anchor cable length was 8.6 m. The equivalent layer method was utilized to simulate the grouting effect30. The reinforcement range was set to 2.28 m, based on the theoretically calculated damage residual zone, to demonstrate the grouting reinforcement effect. Pressure relief holes, 153 mm in diameter, were drilled at 0° and 90° within the roadway, extending beyond the plastic zone into the surrounding rock, with a length of 17 m and spaced at 2 m intervals.

Analysis of effectiveness of grading control

A detailed analysis of the stress and deformation distribution in the surrounding rock was conducted for each support scheme. Figure 10 illustrates the stress distribution cloud diagrams for the different schemes. As expected, roadway excavation induced stress concentration within the surrounding rock, forming a high-stress zone. Notably, the extent of this high-stress zone progressively decreased from Scheme 1 to Scheme 3. However, Scheme 4 exhibited a stress diffusion phenomenon around the pressure relief boreholes.

In Scheme 1, the normalized stress peak in the surrounding rock was 0.95, located 3.49 m from the roadway surface. The stress distribution pattern in Scheme 2 was similar to that of Scheme 1, but the stress peak shifted closer to the surface, occurring at 2.86 m, with a normalized peak stress of 0.98. In Scheme 3, following grouting treatment, the stress peak further increased, reaching the highest value among all four schemes, with the peak position moving to 1.83 m from the roadway surface. Additionally, compared to Scheme 2, the stress in Scheme 3 increased within the depth range of 0 to 1.83 m, indicating that anchor injection enhanced the bearing capacity of the shallow surrounding rock. In Scheme 4, the stress in the roadway side’s surrounding rock was effectively relieved through grading control and the construction of pressure relief holes. Under identical simulation conditions, the high-stress area on the side was segmented by the pressure relief holes, reducing the normalized stress peak to 0.903, which is 9.7% lower than that of Scheme 3, with the peak position slightly shifting to 2.30 m in depth. Scheme 4 successfully mitigated the stress concentration in the surrounding rock, demonstrating the efficacy of the grading control method in alleviating stress concentration.

Figure 11 presents a statistical analysis of the deformation of the surrounding rock at the top of the roadway surface. In Scheme 1, the surrounding rock exhibits the greatest deformation. The implementation of controlled support in Scheme 2 provides additional radial support, reducing the deformation by 18.17%. Scheme 3 further diminishes the deformation compared to Scheme 2, achieving a reduction of 28.02%. Scheme 4 incorporates borehole pressure relief control, which affects the deformation of the surrounding rock. Although there is a slight increase of 2.30% in deformation compared to Scheme 3, it remains within a manageable range. Moreover, Scheme 4 effectively alleviates pressure on the shallow surrounding rock, contributing to the long-term stability of the rock mass.

The numerical simulation results indicate that the plastic damage depth of the surrounding rock decreases under different support schemes, addressing the progressive failure of the damaged residual and plastic zones around the roadway. The Level I and Level II controls of the PRU system primarily target the deep rock mass, inhibiting further damage and enhancing the load-bearing capacity of the surrounding rock. Level III control mitigates stress concentration in the deep rock mass by altering its stress state. This analysis confirms the efficacy of the grading control method in enhancing the stability of the surrounding rock.

Conclusions

To investigate the damage and failure mechanisms of surrounding rock in high-stress roadways and to develop effective control measures, an elastic-plastic theoretical model was established to analyze surrounding rock damage and fracture. This study revealed the variation patterns of damage and fracture zones in the surrounding rock and proposed a grading control method. The effectiveness of this grading control approach was verified through numerical simulation, leading to the following key conclusions:

-

1.

The surrounding rock was divided into four zones from the roadway wall outward: damage residual zone, plastic damage zone, elastic zone, and original rock stress zone. The study clarified the extents of the residual damage and plastic damage zones, highlighting the influence of rock damage on these areas.

-

2.

As the initial stress \({P_0}\)increased, both the damage residual boundary (\({r_b}\)) and the plastic zone radius (\({r_s}\)) showed a nonlinear increase, leading to an increase in the peak load on the surrounding rock. An increase in parameter B resulted in decreases in \({r_b}\) and \({r_s}\), as well as a reduction in peak load. With a higher rock damage degree \({D_3}\), both \({r_b}\) and \({r_s}\)increased, though the peak stress remained relatively unchanged, primarily affecting the stress distribution in the residual zone. An increase in the rock brittle characteristic parameter i expanded the damage range, but the effect was not significant. Increased support resistance \({P_s}\) led to decreases in \({r_b}\) and \({r_s}\), with a slower change rate, mainly affecting stress distribution in the damage residual zone.

-

3.

Based on the control concept aimed at preventing crack initiation, limiting crack development, and reducing stress concentration, a grading control strategy was developed, consisting of three levels: Level I support for crack prevention, Level II reinforcement with anchor injection for crack reduction, and Level III local drilling for pressure relief. When grading control measures are applied to the surrounding rock under the same conditions, the results show a significant reduction in stress concentration and a marked decrease in surrounding rock deformation. This approach effectively enhances the stability of the surrounding rock, ensuring a more controlled and reliable response to excavation and stress redistribution in high-stress environments.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Cai, M. F. & Brown, E. T. Challenges in the mining and utilization of deep mineral resources. Engineering. 34, 432–433 (2017).

Huang, X. et al. Damage assessment of high-stress brittle surrounding rock masses in a deep large-span high-sidewall underground cavern: in situ measurement and numerical simulation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 161, 108273 (2024).

Zhao, G. M. et al. Stress and load-bearing structure analysis of the surrounding rock in a soft broken roadway. Arab. J. Geosci. 13, 1134 (2020).

Liu, C. Y. et al. Experimental study on failure characteristics of single-sided unloading rock under different intermediate principal stress conditions. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 33(3), 275–287 (2023).

Luo, Z. W. et al. Analytical solution and factors influencing the tunnel plastic zone under a nonuniform stress field. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 28, 3016–3032 (2024).

Peng, R. et al. Multi-echelon support method to limit asymmetry instability in different lithology roadways under high ground stress. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 108, 103681 (2021).

Chen, S. J. et al. Stress evolution of deep surrounding rock under characteristics of bi-modulus and strength drop. J. Cent. South. Univ. 29(2), 680–692 (2022).

Wei, J. et al. Deformation and failure mechanism of surrounding rock in deep soft rock tunnels considering rock rheology and different strength criteria. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 57(1), 545–580 (2024).

Yao, Q. C. et al. Analysis of surrounding rock pressure of deep buried tunnel considering the influence of seepage. Geofluids 1, 3644147 (2022).

Jiang, H. B. et al. Stability analysis of the surrounding rock-lining structure in deep-buried hydraulic tunnels having seepage effect. Sustainability 14, 16586 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Analytical Solution for interaction between tunnel surrounding rock and supports in red sandstone stratum. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 27(11), 4993–5007 (2023).

Su, T. M. et al. Mechanical analysis of the circular tunnel considering the interaction between the ground response curve and support response curve. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 7892010. (2018).

Zhu, C. Q. et al. Comparative analysis on elastic-plastic analytical methods for tunnel surrounding rocks. Tehnicki Vjesnik-technical Gaz. 27(2), 374–381 (2020).

Dong, Y. C. et al. Variable model for mechanical parameters of soft rock and elastoplastic solutions for tunnels considering the influence of confining pressure. Front. Earth Sci. 11, 1143003 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Elastoplastic coupling solution of circular openings in strain-softening rock mass considering pressure-dependent effect. Int. J. Geomech. 18, 04017132 (2018).

Zou, J. F., Wei, A. & Yang, T. Elasto-plastic solution for shallow tunnel in semi-infinite space. Appl. Math. Model. 64, 669–687 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. Deformation and failure mechanism of surrounding rocks in crossed-roadway and its support strategy. Eng. Fail. Anal. 116, 104743 (2020).

Zhu, C. et al. Research on the three shells cooperative support technology of largesection chambers in deep mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 31(4), 665–680 (2021).

Kang, H. P. et al. A combined ground support-rock modification-destressing strategy for 1000-m deep roadways in extreme squeezing ground condition. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 142, 104746 (2021).

Xie, Z. Z. et al. Model experiment research on HPTL anchoring technology for coal-rock composite roof in deep roadway. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 2381 (2023).

Xie, S. R. et al. Failure analysis and control mechanism of gob-side entry retention with a 1.7-m flexible-formwork concrete wall: a case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 117, 104816 (2020).

Yu, W. J. & Li, K. Deformation mechanism and control technology of surrounding rock in the deep-buried large-span chamber. Geofluids 1, 881319 (2020).

Zhang, Y. Y. et al. Step by step and combined supporting technique with allowable deformation plus limiting shape for soft rock roadway. Heliyon 10(11), e32200 (2024).

Li, G. et al. Integrated early warning and reinforcement support system for soft rock tunnels: a novel approach utilizing catastrophe theory and energy transfer laws. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 150, 105869 (2024).

Jiang, Z. H. et al. Research on cooperative control method of comprehensive pressure relief and anchor grouting reinforcement in deep mining roadways. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources. 10(1), 79 (2024). .

Wu, X. Y. et al. Failure mechanism and stability control of surrounding rock in mining roadway with gentle slope and close distance. Eng. Fail. Anal. 152, 107489 (2023).

Guo, X. F. et al. Analytical solutions for characteristic radii of circular roadway surrounding rock plastic zone and their application. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 29(2), 263–272 (2018).

Zhang, X. B. et al. Analysis on surrounding rock of circular roadway considering nonlinear brittle dam-age and intermediate principal stress. J. China Coal Soc. 39, 339–346 (2014).

Liu, C. Y. et al. Experimental investigation on failure process and spatio-temporal evolution of rockburst in granite with a prefabricated circular hole. J. Cent. South. Univ. 27(10), 2930–2944 (2020).

Huang, B. X. et al. Large deformation theory of rheology and structural instability of the surrounding rock in deep mining roadway. J. China Coal Soc. 45(3), 911–926 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the discipline innovation team of Anhui University of Science and Technology.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Foundation for High-level Talents of Anhui University of Science and Technology, China (No. 2023yjrc131), the Coal Mine Safety Mining Equipment Innovation Center of Anhui Province, China (No. CMSMEICAP2024006), the Open Research Grant of Joint National-Local Engineering Research Centre for Safe and Precise Coal Mining, China (No. EC2023026), the National Key Research and Development Project of China (No. 2023YFC2907602), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52404068 and 52004006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The overarching research goals were developed by Liu Chongyan, Zhao Guangming. Pan Cheng, Xu Wensong provided the experimental methods, and analyzed the experimental data. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by Liu Chongyan, Zhao Guangming, Pan Cheng. Meng Xiangrui, Liu Wenjie revised and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chongyan, L., Guangming, Z., Cheng, P. et al. Damage analysis and grading control technology of surrounding rock in high geo-stress roadway. Sci Rep 15, 1188 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85647-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85647-2