Abstract

Background: Environmental metal exposure has been implicated in the development of digestive tract cancers, although the specific associations remain poorly defined. This study aimed to investigate the relationship between blood metal levels and the risk of digestive tract cancers among U.S. adults. Methods: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018, including 13,467 participants aged 20 years and older, were analyzed. Nine blood metals were measured. Multivariable logistic regression, restricted cubic spline models, and subgroup analyses were employed to assess the associations between metal levels and cancer risk. Additionally, a Random Forest (RF) model was used for cancer risk prediction. Results: Among the participants, 9 had esophagus cancer (EC), 11 had gastric cancer (GC), and 83 had colorectal cancer (CRC). Compared to healthy controls, EC patients exhibited significantly higher blood levels of potassium (K, 4.40 vs. 4.00 mmol/L), cadmium (Cd, 12.46 vs. 2.49 µg/L), and lead (Pb, 0.09 vs. 0.05 µg/L). GC patients had elevated Pb levels (0.08 vs. 0.05 µg/L), while CRC patients showed higher concentrations of Cd (3.11 vs. 2.49 µg/L) and Pb (0.06 vs. 0.04 µg/L). Logistic regression analysis revealed significant associations between higher K (odds ratio [OR] = 7.58, 95% CI: 3.48–16.48, P < 0.0001), Cd (OR = 1.06, 95% CI: 1.04–1.08, P < 0.0001), and Pb (OR = 7.60, 95% CI: 3.26–17.72, P < 0.0001) levels and EC risk. Pb was also significantly associated with GC (OR = 5.26, 95% CI: 2.11–13.10, P < 0.001). The RF model showed an accuracy of 76% in predicting cancer risk, with SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis highlighting Cd and iron (Fe) as key contributors. Conclusions: The study reveals a positive association between certain blood metals and digestive tract cancer risk, suggesting that limiting exposure to these metals may serve as a potential preventive measure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digestive tract cancers, encompassing esophageal cancer (EC), gastric cancer (GC), and colorectal cancer (CRC), remain among the leading causes of cancer-related mortality globally1. Despite advances in endoscopic techniques and surgical interventions, which have improved early detection and treatment outcomes, the prognosis for patients with advanced-stage digestive tract cancers remains poor. This highlights the urgent need for breakthroughs in both prevention and treatment strategies to mitigate the growing global burden posed by these malignancies2,3,4. Therefore, the early identification of high-risk factors and prompt intervention are essential to improve patient outcomes and reduce mortality.

Environmental metals, derived from food, water, and air, have been recognized as potential contributors to adverse human health outcomes5. Chronic exposure to environmental metals has been implicated in the dysfunction of various organ systems. For instance, research has linked heavy metal exposure to increased risks of cardiovascular diseases, such as stroke and coronary artery disease6. Additionally, neurotoxic metals, including cadmium, lead, mercury, and manganese, have been associated with neurodevelopmental delays, cognitive impairment, and the onset of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease7,8. Long-term exposure to heavy metals also induces oxidative stress, resulting in renal damage9,10. Importantly, certain environmental metals have been found to play a role in carcinogenesis, with elevated levels detected in various cancers, including those of the digestive tract11,12. Given the pervasive nature of environmental contamination, particularly in urban centers and developing countries, understanding the relationship between metal exposure and the risk of digestive tract cancers is critical.

Recent advancements in machine learning (ML) offer new opportunities for cancer research by facilitating the analysis of complex datasets and uncovering hidden patterns. In this study, we employ ML techniques, including Random Forest, to investigate the association between environmental metal exposure and the risk of digestive tract cancer. ML allows for the identification of non-linear relationships and provides a ranking of the most influential metals involved in cancer risk prediction. Utilizing SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), we aim to pinpoint the key metals driving this association, offering valuable insights for targeted public health interventions.

The objective of this study is to examine the relationship between blood levels of nine metals and digestive tract cancer risk among adults in the United States, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Our goal is to contribute to the growing body of evidence on environmental risk factors and to support public health initiatives aimed at the prevention of digestive tract cancers.

Methods

Study design and population

Data for current study were collected from NHANES database, a multistage stratified composite design survey that aims to depict the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population. A total of 13,467 participants over 20 years old, who had sufficient demographic and medical data, were included in this cross-sectional study. These participants were representative of 150,440,432 individuals after applying the appropriate weighting. To ensure a robust analysis, 4 consecutive NHANES surveys conducted between 2011 and 2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016 and 2017–2018 were consolidated into a single analytic sample. Individuals with missing or incomplete information were excluded from the study population. The sample collection and pre-processing process is shown in Figure S1 in the Supplementary Information.

Variable selection

In our study, the diagnoses of digestive tract cancer (EC, GC or CRC) were defined based on responses obtained from the Medical Status Questionnaire: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or malignancy?” and “What kind of cancer was it?”. Those participants who indicated solely “Esophagus (Esophageal) Cancer,” “Stomach Cancer,” or “Colon/Rectum (Rectal) Cancer” were classified as the outcome variables for our analysis.

We assessed demographic covariates including age, gender, race, education state, poverty-income ratio (PIR) which indicated the poverty status and smoke history as the baseline information.

Measurement of blood metals

In our study, blood metals were used to reflect metal exposure. The blood of participants was collected at the mobile examination center (MEC) and the detailed test methods and quality control of blood metal were available on the NHANES website (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes). The following 9 blood metals were including in current study: Sodium (Na, \(\:mmol\)), Calcium (Ca, \(\:mmol\)), Potassium (K, \(\:mmol\)), Iron (Fe, \(\:\upmu\:mol\)), Cadmium (Cd, \(\:\upmu\:mol\)), Lead (Pb, \(\:\upmu\:mol\)), Mercury (Hg, \(\:\upmu\:mol\)), Manganese (Mn, \(\:\upmu\:mol\)) and Selenium (Se, \(\:\upmu\:mol\)).

Statistical analysis

The study population was divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of self-reported EC, GC, or CRC. Characteristics were analyzed for comparison between the groups. Continuous variables, which did not follow a normal distribution, were expressed as the median with interquartile range (IQR). The significance of differences between the two groups was assessed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were described using frequency and percent. The distribution of categorical variables was evaluated using the Pearson chi-squared test. Statistical evaluation of the data was conducted using R 4.1.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).

“Survey” package was used to adjust complex sampling weights for current study for the stratified, multi-stage probabilistic sampling approach of NHANES. Two-year cycle weights were divided by 4 to reflect 8 survey years. Weighted quantile sum (WQS) regression was applied by using “gWQS” package to explore the overall effects of metals on digestive tract cancers. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was performed to identify the sensitivity and specificity of different blood metal to predict the risk of digestive tract cancers. We used “rms” package to conduct restricted cubic splines (RCS) logistic analysis and calculate p value for nonlinearity. Weighted logistic multivariate analysis was utilized to explore the association between blood metal and digestive tract cancers. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to assess the association. Three different models were used to decrease the influence of potential confounders. Model 1 was the crude model. Model 2 was adjusted for age and gender. Model 3: adjusted for age, gender, race, PIR and education state.

Machine learning analysis

To further explore the response mechanism of cancer patients to blood metals, this study extracted all positive samples as the dataset for training the ML model. The input features included gender (1 for male, 0 for female), ethnicity (0 for Other Race - Including Multi-Racial, 1 for Other Hispanic, 2 for Non-Hispanic White, 3 for Non-Hispanic Black, and 4 for Mexican American), education (0 for Less than high school, 1 for High school graduate, 2 for Some college, and 3 for College graduate or above), and smoke (0 for no, 1 for yes). The output target was the type of digestive tract cancer (0 for Esophagus Cancer, 1 for Gastric Cancer, and 2 for Colorectal Cancer). The Spearman correlation matrix was used to preliminarily analyze the correlation between the parameters in the dataset.

This study constructed a Random Forest (RF) model to predict the types of digestive tract cancer, with the open-source code of the model obtained from Scikit-Learn (version 1.0.2). The dataset was divided into a training set and a testing set at a ratio of 80:20. Furthermore, to further enhance the predictive performance of the model, two hyperparameters of the RF (the number of trees and the maximum depth) were optimized using the grid search method. The predictive accuracy of the model was evaluated using accuracy, and the prediction results were visualized using a confusion matrix. The formula for calculating accuracy is as follows:

Finally, the relationships between input features and the output target were analyzed using SHAP, a method based on cooperative game theory that quantifies each feature’s contribution to the model’s prediction. SHAP offers transparent, consistent, and interpretable insights into how input features influence the output, providing a reliable way to explain complex models. In this study, SHAP was used to assess feature importance and partial dependence, helping to identify key blood metal concentrations affecting gastrointestinal cancer risk.

Results

Characteristics of included participants

The flow chart for the selection of participants was shown in Fig. 1. Among 13,467 participants, there were 9 individuals with EC (represented 60,495 people after weighting), 11 individuals with GC (represented 75,369 people after weighting) and 83 individuals with CRC (represented 829,948 people after weighting). A summary of the characteristics of these individuals, stratified by the presence or absence of digestive tract cancer was shown in Table 1. Compared to those without digestive tract cancers, people with EC had an older age (65 vs. 47, P < 0.0001), more smoke rate (69.84% vs. 18.37%, P < 0.001) and lower PIR (1.22 vs. 2.95, P < 0.0001). Individuals with GC had an older age (48 vs. 47, P = 0.04) and lower PIR (2.12 vs. 2.95, P < 0.0001). As for individuals with CRC, an older age (68 vs. 47, P < 0.0001) and a higher proportion of white population (p = 0.003) was observed.

Blood metal and digestive tract cancers

The blood metal levels of participants with and without digestive tract cancer were compared and presented in Table 2. Individuals diagnosed with EC exhibited significantly higher blood K (4.40 vs. 4.00, P < 0.0001), Cd (12.46 vs. 2.49, P < 0.0001) and Pb (0.09 vs. 0.05, P = 0.001) levels compared to those without EC. Likewise, individuals with GC demonstrated higher blood Pb levels (0.08 vs. 0.05, P < 0.001). Comparatively, participants with CRC were found to have elevated blood Cd (3.11 vs. 2.49, P = 0.01) and Pb (0.06 vs. 0.04, P = 0.002). In contrast, blood Na, Ca, Fe, Hg, Mn, and Se levels showed no significant differences between groups with and without digestive tract cancers. Furthermore, given the relationship between metal metabolism and kidney function, the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was assessed as an indicator of renal health. Compared to health controls, patients with EC (76.77 vs. 95.81, P = 0.002), GC (91.60 vs. 95.81, P = 0.03) and CRC (79.65 vs. 95.89, P < 0.0001) had significant lower eGFR. These findings suggested a deterioration in kidney function among cancer patients relative to healthy individuals.

The WQS index of mixed metals was positively associated with EC risk (OR = 12.58, 95%CI: 1.56-101.18, p = 0.003) and the highest weighted metals in WQS models was Cd, K and Se. However, for GC, the WQS index of mixed metals showed no significant associations (OR = 2.79, 95%CI: 0.63–12.25, p = 0.172). Additionally, positive linkage between the WQS index of mixed metals and CRC risk was (OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.17–3.27, p = 0.009) observed, the leading weighted metals were Cd, Na and Pb (Fig. 2).

We then performed analyses to confirm the stability of the correlation between blood levels of K, Cd, and Pb and the risk of digestive tract cancers across various populations (Tables 3 and 4, Table S1). In the case of EC, analyses that stratified by age showed that blood K (< 60: OR = 18.06, 95%CI: 3.61–90.28, p < 0.001; ≥60: OR = 3.72, 95%CI: 1.21–11.41, p = 0.02), Cd (< 60: OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 1.05–1.09, p < 0.0001; ≥60: OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02–1.08, p < 0.001) and Pb (< 60: OR = 7.00, 95%CI: 2.90-16.91, p < 0.0001; ≥60: OR = 125.73, 95%CI: 4.23-3732.79, p = 0.01) were associated higher EC risk in both population whether they were younger or older than 60. Moreover, the positive association of blood Cd (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.06–1.10, p < 0.0001) and Pb (OR = 7.03, 95%CI: 3.13–15.82, p < 0.0001) was found in male and K (OR = 9.48, 95%CI: 4.80-18.73, p < 0.0001) in female. In terms of race, our analyses indicated that blood Cd (OR = 1.09, 95%CI: 1.05–1.12, p < 0.0001) and Pb (OR = 24.23, 95%CI: 11.22–52.35, p < 0.0001) was associated with higher EC risk in black population. And the positive relationship between blood K (OR = 11.84, 95%CI: 5.46–25.66, p < 0.0001), Cd (OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 1.04–1.09, p < 0.0001) and Pb (OR = 30.99, 95%CI: 5.12-187.37, p < 0.001) and EC was found significant strong in white population. The smokers showed a significant association between blood K (OR = 6.91, 95%CI: 1.28–37.36, p = 0.03), Cd (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 1.01–1.04, p = 0.004) and Pb (OR = 15.14, 95%CI: 7.00-32.71, p < 0.0001) and EC. For non-smokers, only blood K (OR = 11.07, 95%CI: 6.11–20.06, p < 0.0001) was found to be associated with higher EC risk. For individuals with GC, our analysis showed that blood Pb showed significant strong association with GC risk in people younger (OR = 3.49, 95%CI: 1.66–7.35, p = 0.001) and older (OR = 115.27, 95%CI: 2.03-6560.70, p = 0.02) than 60, both males (OR = 6.35, 95%CI: 2.38–16.92, p < 0.001) and females (OR = 35.97, 95%CI: 4.96-260.96, p < 0.001), black (OR = 17.88, 95%CI: 9.67–33.04, p < 0.0001), white (OR = 6.21, 95%CI: 1.38–28.06, p = 0.02) and other Hispanic (OR = 15.96, 95%CI: 4.44–57.35, p < 0.0001) populations, both smokers (OR = 15.74, 95%CI: 5.28–46.92, p < 0.0001) and non-smokers (OR = 3.25, 95%CI: 1.65–6.41, p < 0.001). As for individuals with CRC, the association between blood Cd and CRC was only found in other race population (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02–1.07, p < 0.001) and non-smokers (OR = 1.13, 95%CI: 1.06–1.20, p < 0.001). And blood Pb was associated with higher CRC risk in those younger than 60 (OR = 4.21, 95%CI: 1.87–9.50, p < 0.001), females (OR = 164.13, 95%CI: 10.08-2673.69, p < 0.001), black (OR = 10.69, 95%CI: 2.43–47.04, p = 0.002), white (OR = 9.53, 95%CI: 1.32–68.95, p = 0.03), other Hispanic (OR = 7.47, 95%CI: 1.84–30.22, p = 0.01) and other race (OR = 30.82, 95%CI: 7.30-130.10, p < 0.0001) populations, both smokers (OR = 6.66, 95%CI: 2.87–15.45, p < 0.0001) and non-smokers (OR = 3.89, 95%CI: 1.42–10.68, p = 0.01). These findings provide valuable insights into the potential role of blood metal levels in the development of digestive tract cancers among diverse population groups.

Blood potassium, cadmium and lead with digestive tract cancers

We conducted logistic regression analysis to evaluate the OR of three different kinds of digestive tract cancers across blood metal levels by adjusting potential confounders. Across all three models, blood K, Cd, and Pb showed significant positive associations with EC risk. Specifically, for blood K, the OR was 7.58 (95% CI: 3.48–16.48, p < 0.0001) in model 1, 4.30 (95% CI: 1.58–11.72, p = 0.01) in model 2, and 3.91 (95% CI: 1.36–11.27, p = 0.01) in model 3. Similarly, Cd had OR of 1.06, 1.06, and 1.09 in the respective models (all p < 0.0001). For Pb, the OR were 7.60, 10.13, and 15.21 in models 1, 2, and 3, respectively (all p < 0.0001). In the case of GC, blood Pb was found to be significantly associated with GC risk in all three models, with OR of 5.26, 7.06, and 6.09 (p < 0.001; p < 0.001; p = 0.002). However, no significant association was observed between blood Cd and CRC. Blood Pb was found to be significantly associated with higher CRC risk only in the crude model, with an OR of 4.17 (95% CI: 1.66–10.49, p = 0.003) (Table 5). These results suggest that individuals with elevated levels of blood Pb have a higher risk of developing both EC and GC, while those with higher levels of blood K and Cd are more likely to develop EC.

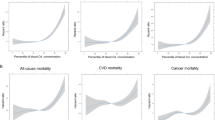

The ROC curve analysis revealed the predictive capabilities of blood K (AUC = 0.7952), Cd (AUC = 0.8273) and Pb (AUC = 0.7603) in assessing the risk of EC. Additionally, in the case of GC, the ROC curve analysis indicated that blood Pb could be a predictor for GC risk with a moderate AUC value of 0.6853 (Fig. 3, Figure S1). Subsequently, utilizing RCS logistic analysis, a linear relationship was observed between blood K (p for nonlinearity = 0.6507), Cd (p for nonlinearity = 0.0774) and Pb (p for nonlinearity = 0.1210) and the risk of EC (Fig. 4A-C). Similarly, for GC, blood Pb exhibited a linear relationship with the risk of the disease (p for nonlinearity = 0.1356) (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that elevated levels of specific blood metals are associated with increased risks of both EC and GC, highlighting the significance of metal exposure in the development of these cancers.

Machine learning-based deep analysis of the response to blood metals in cancer-affected populations

The Spearman correlation matrix between the dataset parameters is shown in Fig. 5A. Gender was negatively correlated with Ca concentration (r = -0.36, p < 0.001). Smoke was positively correlated with Cd (r = 0.59, p < 0.001) and Pb (r = 0.30, p < 0.01). These results indicated that gender and smoking status may influence the concentration of blood metals in cancer patients. Further analysis also revealed that smoking rate and K concentration are negatively correlated with cancer type (EC = 0, GC = 1, CRC = 2) (r = -0.40, p < 0.001; r = -0.23, p < 0.05). PIR was positively correlated with cancer type (r = 0.27, p < 0.01). This suggested that among cancer patients, those with smoking habits and higher blood K concentrations may be more prone to EC, while individuals with higher PIR were more susceptible to CRC.

In-depth analysis of cancer-affected individuals based on machine learning models. (A) Spearman correlation matrix of input parameters; (B) optimization of hyperparameters for the Random Forest (RF) model based on accuracy; (C) confusion matrix of the RF model; (D) feature importance analysis based on SHAP.

In the process of building a ML model, optimizing the hyperparameters of the model is essential. This study utilized grid search to simultaneously optimize the number of trees and the maximum depth in the RF. The setting of the hyperparameter range depends on the number of features and data samples in the dataset. Referring to previous research13, this study set the number of RF trees to range from 2 to 50 and the maximum number of features to range from 1 to 30. The hyperparameters that could achieve the highest accuracy were selected as the optimal hyperparameters for the model. Figure 5B illustrates the process of hyperparameter optimization. The results indicated that the optimal hyperparameters for RF are a tree count of 12 and a maximum depth of 4. After obtaining the optimal hyperparameters for RF, this study continued to train and test the model. Figure 5C displays the results of RF predictions for gastrointestinal cancer. For three different types of gastrointestinal cancer (EC, GC, and CRC), the prediction accuracy of RF reached 0.76. This result indicated that the predictive performance of RF was relatively good, warranting further analysis of RF.

This study analyzed the feature importance and partial dependence of RF using SHAP (Figs. 5D and 6). Through feature importance analysis, it was found that Cd (ranked first) had the greatest impact on gastrointestinal cancer (Fig. 5D). Its total SHAP value was 0.098, accounting for 16.5% of all features. This indicated that the concentration of Cd in the blood was the primary feature affecting gastrointestinal cancer. Additionally, an interesting observation is that Fe (ranked second) had a total SHAP value of 0.097, suggesting that it is also a feature with high impact, which was not identified in previous models. However, Pb (ranked tenth) had a total SHAP value of only 0.025. This may be due to the high correlation between Pb and Cd (r = 0.40, p < 0.001), with Cd sharing some of Pb’s SHAP value. Furthermore, for EC and CRC, Cd had the highest SHAP values, which were 0.046 and 0.047, respectively. For GC, Fe had the highest SHAP value, which was 0.046. This indicated that Cd had a greater impact on EC and CRC, while Fe had a greater impact on GC.

To further explore the relationship between blood metals and the risk of gastrointestinal cancer, this study conducted additional investigations using partial dependence plots (Fig. 6, Figure S2). The x-axis represents the feature values, and the y-axis represents the probability of developing a certain type of gastrointestinal cancer given that feature value. Each point represents a sample, and the aggregation of multiple points reveals the overall trend of influence. Cd, as the feature with the greatest impact on gastrointestinal cancer (Fig. 5D), when its concentration exceeded 10 µmol, significantly increased the risk of EC (Fig. 6A-a), but decreased the risk of CRC (Fig. 6A-c). However, its impact on the risk of GC did not show a clear trend (Fig. 6A-b), which may be due to the lower SHAP value of Cd for GC (Fig. 5D). Fe, also a feature with a relatively high impact (Fig. 5D), was found to sharply increase the risk of CRC when its concentration exceeds 7.5 µmol (Fig. 6B-c). Additionally, when K was above 4.0 mmol, the risk of EC and GC was higher, peaking at 4.3 mmol for K. At this point, the risk of CRC was lower (Fig. 6C). This was consistent with the results of the aforementioned Spearman correlation matrix (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the study also found that when Se was above 2.1 µmol, the probability of developing EC and CRC was higher compared to GC (Fig. 6D). When Mn was above 150 µmol, the probability of developing EC and GC was higher compared to CRC (Fig. 6E).

Discussion

With the rapid industrial development and modernization contributing to the global issue of environmental pollution by heavy metal pollutants in soil, water, and air, the study was conducted to investigate the potential impact of environmental metal exposure on the risk of digestive tract cancer. This NHANES-based cross-sectional study aimed to elucidate the relationships between 9 different blood metals and the incidence of digestive tract cancer. These blood metals were selected based on their relevance to human health and prevalence in the body. Included in this selection are common serum electrolytes, such as K, which are essential for cellular function and physiological processes like nerve conduction and muscle function. Additionally, the selection includes widely studied heavy metals, such as Cd, Pb and As, known for their toxic effects and potential links to carcinogenesis, particularly in digestive tract cancers. These metals are frequently measured in both clinical and environmental studies, facilitating their testing and analysis.

Our analysis revealed positive associations between blood K, Cd, Pb and EC risk, as well as a link between blood Pb and GC risk. However, no significant association was observed between blood metals and CRC risk. A deeper analysis of cancer-affected populations using machine learning indicated that higher iron (Fe) concentrations (> 7.5 µmol) in the blood may increase CRC risk (Fig. 6B-c). Subgroup analysis indicated that blood K showed a consistent association with EC across both age groups, female participants, individuals of white ethnicity, both smokers and non-smokers. Meanwhile, the association between blood Cd and Pb with EC was particularly strong across both age groups, male participants, and individuals of black and white ethnicities, as well as smokers. Regarding GC, a positive association was found between blood Pb and GC risk across both age groups, genders, individuals of black, white and other Hispanic ethnicities, both smokers and non-smokers. Our study results suggest that certain environmental metal exposures may elevate the risks of digestive tract cancer development.

In our study, we made an intriguing discovery that K, not traditionally considered as a heavy metal, demonstrated a positive association with EC. Moreover, the machine learning analysis also found that the risk of developing EC was highest when the K concentration was 4.3 mmol (Fig. 6C-a). Physiologically, K plays an essential role in maintain the function of ion channels. Neoplastic transformation, a hallmark of cancer development, is characterized by disruptions in K transport across cell membranes14. K channels, critical for the maintenance of cancer stemness and the modulation of the tumor microenvironment, have been identified as being upregulated in various tumor types, contributing significantly to cancer initiation, progression and therapy resistance15. These channels also play a key role in regulating membrane potential and cell volume, crucial for the rapid proliferation of tumor cells, which rely on K channels to maintain depolarized membrane potentials16,17. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that K channels aid tumors in adapting to hypoxic conditions and facilitate metastasis18. Despite the absence of direct evidence supporting K as a risk factor for EC, the potential carcinogenicity of K suggests the need for more comprehensive investigation and research.

Cd, classified as a human carcinogen, can lead to adverse effects including an elevated risk of malignancy due to its carcinogenic properties19,20. In our study, we found a strong association between higher blood Cd levels and an increased risk of EC. Further analysis of the cancer-affected population by machine learning revealed a rapid increase in EC risk when the concentration of Cd was greater than 10 µmol (Fig. 6A-a). The general population is exposed to Cd primarily through tobacco smoke inhalation, establishing a close link between Cd exposure and the initiation and progression of lung cancer21. Cd has been reported to increase intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and induce cellular oxidative stress in human bronchial epithelial cells, providing a potential mechanism for the development of Cd-induced lung cancer22. Various mechanisms have been identified that contribute to the carcinogenic effects of Cd23. Studies have shown that Cd disrupts crucial cellular responses to DNA damage, including nucleotide excision repair, base excision repair, and mismatch repair processes, ultimately leading to malignancy24. Moreover, Cd promotes cell proliferation and inhibits negative growth signals, with evidence indicating the downregulation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 during Cd exposure25,26,27. Specifically focusing on EC, one study based on China population revealed a positive association between soil Cd level and increased EC mortality28. Yang et al. demonstrated that Cd could upregulate the expression of CDK6 in human esophageal cells, potentially contributing to the development of EC29. Despite these findings, the exact mechanisms underlying Cd-induced carcinogenicity remain inadequately understood, highlighting the necessity for further research to elucidate this area.

Pb exposure has been identified as a significant risk factor for both EC and GC in the current study, highlighting the potential hazards of Pb in the development of digestive tract cancers. Partial dependence also indicated that only low concentrations of Pb (0.02 mmol) were required to result in higher risks of EC and GC (Figure S1). Human activities such as mining, refining and recycling contribute to the release of Pb into the environment, with gasoline, paint, leaded glass and certain types of batteries being key sources of Pb exposure. According to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Pb and its compounds are classified as potential human carcinogens30. A meta-analysis comprising 12 studies suggested that Pb may act as a risk factor for meningiomas and brain cancers31. Additionally, a NHANES-based study indicated a positive correlation between blood Pb levels and lung cancer mortality32. Evidence from a cross-sectional case-control study revealed a positive association between urinary Pb levels and female breast cancer risk after adjusting for potential confounders (OR = 2.16, 95% CI: 1.18–3.95, p < 0.05)33. Despite these findings, no other studies, apart from the present one, have directly linked Pb exposure to the risk of EC or GC. The mechanisms through which Pb induces tumorigenesis remain largely unexplored. Previous research has shown that Pb exposure could suppress the production of crucial immune cells like T cells, B cells and NK cells, which play essential roles in facilitating tumor growth and metastasis34. Furthermore, Pb exposure can induce oxidative stress and enhance the vulnerability of genes to oxidative damage, thereby increasing the risk of various cancers35. It is evident that further research is necessary to unravel the intricate mechanisms behind Pb-induced carcinogenesis and provide a deeper understanding of its potential role in cancer development. Furthermore, this study found that in the deep analysis of cancer patients using machine learning, Cd and Pb not only exhibit a high correlation but also have a significant impact on both CRC and EC (Fig. 5A and D). This phenomenon may be attributed to the simultaneous intake of Pb and Cd during human diet. Studies have shown that Cd and Pb are heavy metals of the same type, which are easily enriched simultaneously during the growth process of food crops such as rice36.

Our study, which integrated a large-population cross-sectional design with advanced ML model, represented a pioneering effort to investigate the relationship between digestive tract cancer risk and 9 blood metals of environmental origin. By combining traditional statistical analysis with a Random Forest, this study not only confirmed significant associations between blood metals and cancer risk but also provided novel insights into the relative importance of each metal in predicting cancer risk through SHAP. These findings offered a deeper understanding of the carcinogenic impacts of environmental metals and highlighted the urgent need to address improper disposal practices, given their potential role in promoting carcinogenesis.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. Firstly, critical factors such as staging, histologic information, surgery history and survival of involved individuals with digestive tract cancer were not available in the current research, thus hindering subgroup analysis based on these aspects. Secondly, the study predominantly concentrated on the western population, where the incidence of EC and GC is relatively lower compared to regions like East Asia. To improve the generalizability of the results, a more diverse dataset, particularly from Asian populations, should be utilized for further analysis. Finally, it is important to note that this study is cross-sectional in nature, making it challenging to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between blood metal levels and the risk of digestive tract cancer. Although the injection of machine learning model has compensated for this limitation to some extent, more samples are still needed to enhance the generalizability of model predictions and conclusions in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, our study identified a positive link between blood K, cadmium, and lead levels and the risk of EC, along with blood lead levels and GC. The machine learning model further confirmed that K higher than 4.0 mmol, Cd higher than 10 µmol, and Pb higher than 0.02 mmol increased the risk of EC. Pb higher than 0.02 mmol also increased the risk of GC. Fe higher than 7.5 µmol increased the risk of CRC. Further epidemiological studies are necessary to bolster our results.

Data availability

NHANES data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made publicly and freely available without restriction at https:// wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx. The datasets that used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., Wagle, N.S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. Cancer J. Clin. 73 (1), 17–48 (2023).

Feng, R. M., Zong, Y. N., Cao, S. M. & Xu, R. H. Current cancer situation in China: Good or bad news from the 2018 Global Cancer statistics? Cancer Commun. (London, England) 39 (1), 22 (2019).

Morgan, E. et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: Incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut 72 (2), 338–344 (2023).

Thrift, A. P., Wenker, T. N. & El-Serag, H. B. Global burden of gastric cancer: Epidemiological trends, risk factors, screening and prevention. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 20 (5), 338–349 (2023).

Rahman, M. M., Hossain, M. K. F. B., Afrin, S., Saito, T. & Kurasaki, M. Effects of metals on human health and ecosystem. In Design of Materials and Technologies for Environmental Remediation (eds. Tanaka, S., Kurasaki, M., Morikawa, M. & Kamiya, Y.) . 81–119. (Springer Nature Singapore, 2023).

Yang, A. M. et al. Environmental heavy metals and cardiovascular diseases: Status and future direction. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 6 (4), 251–259 (2020).

Sharma, S. et al. Effect of environmental toxicants on neuronal functions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (36), 44906–44921 (2020). 2020/12/01.

Carmona, A., Roudeau, S. & Ortega, R. Molecular mechanisms of environmental metal neurotoxicity: A focus on the interactions of metals with synapse structure and function. Toxics 9(9). (2021).

Yin, G. et al. Effects of environmental heavy metal interactions on renal impairment: Epidemiological evidence from rural northeastern China. Exposure Health 15(4), 869–887 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Urinary levels of 14 metal elements in general population: A region-based exploratory study in China. Toxics 11, 488 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. The role of heavy metals in the development of colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 23 (1), 616 (2023).

Parida, L. & Patel, T. N. Systemic impact of heavy metals and their role in cancer development: A review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 195 (6), 766 (2023).

Zhao, F. et al. Prediction of heavy metals adsorption by hydrochars and identification of critical factors using machine learning algorithms. Bioresour. Technol. 383, 129223 (2023).

Ganser, K. et al. Potassium channels in Cancer. In Pharmacology of Potassium Channels (eds. Gamper, N. & Wang, K.). 253–275. (Springer, 2021).

Wawrzkiewicz-Jałowiecka, A. et al. Potassium channels, glucose metabolism and glycosylation in cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(9). (2023).

Banderali, U., Leanza, L., Eskandari, N. & Gentile, S. Potassium and chloride ion channels in cancer: A novel paradigm for cancer therapeutics. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 183, 135–155 (2022).

Ratanasrimetha, P., Workeneh, B. T. & Seethapathy, H. Sodium and potassium dysregulation in the patient with cancer. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 29(2), 171–79e1 (2022).

Jessica, I., Lisa, L. & Elena, L. Potassium in solid cancers. In Potassium in Human Health (ed. Jie, T.). Ch. 5. (IntechOpen, 2021).

Hartwig, A. Cadmium and cancer. Metal Ions Life Sci. 11, 491–507 (2013).

Cui, Z. G., Ahmed, K., Zaidi, S. F. & Muhammad, J. S. Ins and outs of cadmium-induced carcinogenesis: Mechanism and prevention. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 27, 100372 (2021).

Peana, M. et al. Biological effects of human exposure to environmental cadmium. Biomolecules 13(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13010036 (2022).

Cao, X. et al. Cadmium induced BEAS-2B cells apoptosis and mitochondria damage via MAPK signaling pathway. Chemosphere 263, 128346 (2021).

Hartwig, A. Mechanisms in cadmium-induced carcinogenicity: Recent insights. Biometals Int. J. Role Metal Ions Biol. Biochem. Med. 23 (5), 951–960 (2010).

Nagaraju, R., Kalahasthi, R., Balachandar, R. & Bagepally, B. S. Cadmium exposure and DNA damage (genotoxicity): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 52 (10), 786–798 (2022).

Fang, Y. et al. Downregulation of vdac2 inhibits spermatogenesis via JNK and P53 signalling in mice exposed to cadmium. Toxicol. Lett. 326, 114–122 (2020).

Gao, Y. et al. Assessment spermatogenic cell apoptosis and the transcript levels of metallothionein and p53 in Meretrix meretrix induced by cadmium. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 217, 112230 (2021).

Jung, K. T. & Oh, S. H. The role of autophagy in cadmium-induced acute toxicity in glomerular mesangial cells and tracking polyubiquitination of cytoplasmic p53 as a biomarker. Exp. Mol. Med. 54 (5), 685–696 (2022).

Jiang, A., Gong, L., Ding, H. & Wang, M. Cancer mortality and long-term environmental exposure of cadmium in contaminated community based on a third retrospective cause of death investigation of residents living in the Guangdong Province from 2004 to 2005. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199 (12), 4504–4515 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Cadmium inhibits apoptosis of human esophageal epithelial cells by upregulating CDK6. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 205, 111146 (2020).

Ebrahimi, M. et al. Effects of lead and cadmium on the immune system and cancer progression. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 18 (1), 335–343 (2020).

Meng, Y., Tang, C., Yu, J., Meng, S. & Zhang, W. Exposure to lead increases the risk of meningioma and brain cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. Organ. Soc. Miner. Trace Elem. (GMS). 60, 126474 (2020).

Rhee, J., Graubard, B. I. & Purdue, M. P. Blood lead levels and lung cancer mortality: An updated analysis of NHANES II and III. Cancer Med. 10 (12), 4066–4074 (2021).

Hu, D. et al. Association between urinary lead and female breast cancer: A population-based cross-sectional study. Discov. Med. 35 (179), 1177–1189 (2023).

Metryka, E. et al. Lead (pb) exposure enhances expression of factors associated with inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(6) (2018).

Kasten-Jolly, J. & Lawrence, D. A. Sex-specific effects of developmental lead exposure on the immune-neuroendocrine network. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 334, 142–157 (2017).

Xiao, R. et al. Lime and phosphate amendment can significantly reduce uptake of Cd and Pb by. Field-Grown Rice. 9 (3), 430 (2017).

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Young Scholars Fostering Fund of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CS conceptualized and designed the study and prepared tables. HJ and YZ collected and analyzed data and prepared and reviewed figures. FZ wrote the original draft. YZ and HC provided revisions to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, C., Jiang, H., Zhao, F. et al. Blood metal levels predict digestive tract cancer risk using machine learning in a U.S. cohort. Sci Rep 15, 1285 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85659-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85659-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Predicting the Regulatory Dynamics of AML Disease Progression from Longitudinal Multi-Modal Clinical Data

Journal of Medical Systems (2025)