Abstract

Due to the excellent bending resistance characteristics, open- and closed-section members are widely used in engineering practice. However, the interactions between plates of different sections have a significant effect on the mechanical behavior of members. Therefore, taking those interactions into consideration is a critical step in establishing the analytical model to investigate the static and dynamic behavior of the structures. This investigation proposes a spring plate model to analyze the vibration, static and dynamic buckling of members, in which the deformation of the spring plate is described by coupling polynomials and trigonometric series. The results show that this class of functions can accurately characterize the restraint of plates. The rotational restraint stiffness for single-plate and double-plates constraints are accurately obtained. Subsequently, analytical solutions for vibration and buckling problem are obtained by the Rayleigh–Ritz method. The dynamic buckling region of the members is further obtained using the Bolotin theory. When the frequency of the periodic load is in this region, the dynamic buckling of the structure is triggered. The presented model is provided to be an effective tool for analyzing the vibration and static and dynamic instability of thin-walled structures by comparing the existing results with finite element method (FEM) results. At the same time, understanding the vibration and dynamic behaviors is beneficial for design safely in terms of structural stability, load bearing capacity, and seismic resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thin-walled structures (TWS) have advantages of light weight, high strength, and simplicity in manufacturing, and members made of composite materials are often produced using pultrusion approach. The composite materials have excellent properties of high strength and lightweight and the performance of which is superior to that of their component, so they are widely used in aerospace, marine, construction, defense engineering, and other fields1,2. Consequently, thin-walled structures are often designed with open- or closed-section to enhance their bending stiffness through section type3,4,5. In addition, structures will be subjected to periodic loads such as earthquake wave and wind loading during actual use, leading to dynamic instability and reducing the buckling capacity6. Therefore, studying the vibration characteristics and dynamic buckling behavior of TWS is an essential aspect of engineering safety design7,8.

The dynamic performance of structures is a major issue in safety design. It is necessary to understand the dynamic response of the structure. In recent decades, researchers have conducted a series of analyses on the vibration behavior of TWS with open- or closed-sections. Nguyen et al.9 studied the vibration of TWS with open-section. It was assumed that the mechanical properties of the thin-walled beams followed a power law distribution. The motion equations were obtained using Hamilton’s principle, and solved by numerical method. Considering the out of plane warping, Sheikh and Asadi10 studied the vibration behavior of laminated TWS beams with open- or based on the one-dimensional beam theory.

In addition to the pure mode vibration analysis described above, the members with open-section have a mutual constraint effect due to the cross-section panels. In addition to pure modal vibrations, vibration studies of coupled modes are also essential. Arpaci and Bozdag11 modified the governing equations for coupled bending and torsion vibration of asymmetric open-section beams and provided accurate solutions. Kollár12 investigated the bending-torsional vibrations of orthotropic laminated beams with and calculated their natural frequencies. In addition to free vibration, vibration analysis after buckling of components is also carried out. Considering the shear deformation of section, Vo and Lee13 studied the coupled flexural–torsional vibration and instability of laminated TWS with open-section, and the effects of configuration and axial load on the vibration and buckling behaviors were studied.

The above researches considered the influence of the interaction between plates of open- or closed-section on the vibration response by constructing the full-section deformation. In addition, the study of the mechanical response of open- or closed-section members can be carried out by choosing key plates with restraint provided by attached plates. The boundary conditions of this type of constrained plate usually are different from the classical boundary conditions (such as simply supported or fixed supported on four sides). Based on this assumption, full-section modeling can be avoided and analysis efficiency can be improved. Scholars have conducted relevant studies on atypical boundary conditions. Wu et al.14 used a combination of analytical and numerical approach to determine the frequencies of the thin-walled plate with arbitrary point masses and translational springs. Watkins et al.15 used the eigen sensitivity analysis to obtain an approximate analytical solution of the free vibration of the plate with different boundary conditions. Eisenberger and Duetsch16 presented the equivalent plate model, and this method can also be extended to composite plates, and functionally graded plates with arbitrary sets of boundary conditions.

Besides vibration, structural stability is also a critical consideration in engineering design, which includes buckling under static or dynamic loads. A number of studies was conducted on static buckling of members with open- and closed-section. Higginson et al.17 employed a combined approach of Rayleigh–Ritz method and discrete plate theory to study the local buckling of laminated TWS with different configurations. Debski et al.18 performed experiments to study on the local buckling, post-buckling characteristic of TWS with C-section columns subjected to a constant rate of end shortening. Liu et al.19 also analyzed the composite laminated open-section beams through static buckling experiments. In the above study, it can be observed that the plate interaction plays an important role in the global deformation of the member.

Researchers have also employed restrained plate model to investigate the buckling characteristic of open- and closed-section members. Kollár20 obtained the solutions for the buckling problem of unidirectionally loaded plates with free and rotationally restrained unloaded edges. Tenenbaum and Eisenberger21 analyzed the instability of plates with rotationally restrained conditions using series form solution. Shabanijafroudi et al.22 used the energy method to study the effect of rotational restraint on the shear instability of composite curved plates, and studied the effects of geometric dimensions and restraint stiffness on the instability behavior. Huang and Qiao et al.22 investigated the buckling of laminates under partial compression. They modeled the web as a plate with rotational restraints, and studied the effects of rotational restraint stiffness on the buckling performance. Qiao and Shan et al.23 discretized the interaction between plates as elastic restraints and performed buckling analysis on simply supported orthotropic plates under in-plane force. In the above study, the interaction mechanism of cross-section plates is still limited by the static buckling analysis.

In addition to static buckling, structures may experience dynamic instability under cyclic loading. Therefore, it is crucial to find the relationship between periodic load frequency and structural instability region. Bolotin24 systematically investigate the dynamic instability of structures subjected to in-plane periodic loading, and subsequently studies on dynamic instability of different structures including beams, plates, and shells were conducted. Zhu and Li6 derived theoretical formulas of the dynamic instability region of the Z-section purlin with lateral restraints subject to uplift wind loading using the energy method. Thereafter this model has also been extended to investigate the dynamic buckling of members with C-section25. Wu et al.26 combined the semi-analytical model and the Bolotin approach to analyze the free vibration and dynamic instability of TWS under in-plane loads.

The above studies have systematically studied the instability and vibration behavior of open- or closed-section members. However, there is limited work on the mechanisms of interaction between plates23,27. For this thin-walled structures, the mutual constraint relationship between the plates of the cross-section affects the global deformation mode of the structure. Therefore, in this work, a spring model is presented to consider the additional plate constraint effect to fill this gap. Typical open and closed sections are adopted as examples. Based on the classical plate theory, the explicit expressions of the constrained stiffness of different plates are given. Furthermore, the relative relationship between plate constraints is discussed. Subsequently, the analytical solutions for buckling and vibration frequencies of thin-walled structures are derived. Combined with the Bolotin method, the analytical solution of dynamic instability region is derived. Based on this present model, the influence of local plate interaction on the global instability and vibration behavior of the structure is systematically investigated.

Analytical modeling of the spring plate

Motion equation for spring plates

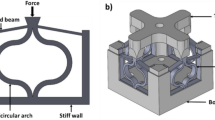

The open- and closed-section members are described in Fig. 1. Considering the effect between the flange and the web, the interaction between the plates is simplified as spring restraints. The two unloaded edges of the web are subject to rotational restraints provided by adjacent plates. This case is named as RR, as shown in Fig. 1a. Similarly, the flange is equivalent as a plate with one restrained and free at the opposite end, named as RF (Fig. 1b).

Here, let \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) be the three coordinate axes, wherein \(x\) along the length direction, \(y\) and \(z\) parallel to the flange and web, respectively. The origin of the coordinates is set at the midplane of the plate.

For both edges rotationally restrained plates (RR) as described in Fig. 1a, how to construct accurate springs to characterize the plate-to-plate restraint becomes the key to establish a spring plate model. Here, the deflection function \(w\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) is obtained by combining interpolation polynomials and trigonometric functions, which can be expressed as23,

where \(k_{L}\) and \(k_{R}\) represent the spring stiffness on the left and right sides of the plate, respectively23. For different cross-sections, the formulas of \(k_{L}\) and \(k_{R}\) are expressed in the supplementary material. The interpolation polynomials and trigonometric functions are represented in deflection in x and y directions, respectively.

For RF plate, the deflection function \(w\left( {x,y,t} \right)\) can be expressed as,

For simply supported boundary conditions, the kinetic energy \(T\), elastic strain energy \(U_{e}\), and external force work \(V\) of the plate can be expressed as follows,

where \(D_{11}\), \(D_{12}\), and \(D_{22}\) are the stiffness coefficients between bending moment and curvature, \(D_{66}\) is the stiffness coefficient between torsion and torsional curvature1. \(\frac{{\partial^{2} w}}{{\partial x^{2} }}\) and \(\frac{{\partial^{2} w}}{{\partial y^{2} }}\) are the curvatures in x and y directions, respectively. \(\frac{\partial w}{{\partial x}}\) and \(\frac{\partial w}{{\partial y}}\) are the rotation angles in x and y directions, respectively. For different constraints, the mass matrix of the plate \(\left[ {\mathbf{M}} \right] = \frac{{\partial^{2} T}}{{\partial \alpha_{m}{\prime} \left( t \right)^{2} }}\) is obtained by substituting Eqs. (1) and (2) into Eq. (3),

RR:

RF:

The stiffness matrix of the plate \(\left[ {\varvec{K}} \right] = \frac{{\partial^{2} U_{e} }}{{\partial \alpha_{m} \left( t \right)^{2} }}\) can be obtained by substituting Eqs. (1) and (2) into Eq. (4) as follows, we have.

RR:

RF:

The geometric stiffness matrix of the plate \(\left[ {{\varvec{K}}_{g} } \right] = \frac{{\partial^{2} V}}{{\partial \alpha_{m} \left( t \right)^{2} }}\) is obtained by substituting Eqs. (1) and (2) into Eq. (5), we have.

RR:

RF:

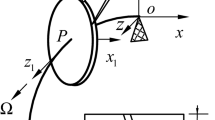

Different from static buckling analysis, dynamic buckling structures are subjected to periodic loads. The motion equation for the dynamic buckling of TWS is given as28,

where \(\left\{ {\mathbf{q}} \right\}\) is the displacement vector, \(\left\{ {{\mathbf{\ddot{q}}}} \right\}\) is the acceleration vector and \(\lambda\) is the loading term. Here, the periodic load is considered, and then the load can be expressed as the following two parts,

where \(\lambda_{s}\) and \(\lambda_{t}\) represent the static and dynamic loading coefficients, respectively. Thus, for a given value α (α < 1 because α[M] = α[M]cr must be less than [M]cr), for a given set of α values, two sets of Ω2 values can be obtained. These two sets of Ω2 values form the dynamic instability region of the structures. \(\Omega { }\) determines the frequency of the periodic load. It should be noted that Eq. (12) is not only suitable for dynamic buckling analysis, but also for free vibration and static instability analysis. For the latter, the formula needs to be degraded and analyzed. The details of the derivation are given in “Solutions for free vibration and static instability” Section.

Solutions for dynamic instability

The present model only addresses the instability problem of structures under harmonic loads. For the instability problem of members under pulse or non-simple harmonic loads, Lyspunov dynamic instability criterion can be used29,30. The Bolotin method can be used to obtain an analytical solution to the frequency of dynamic instability of the structure subjected to periodic loading. The dynamic instability regions are obtained by periodic solutions \(T = 2\pi /{\Omega }\) and \(2T = 4\pi /{\Omega }\)28, and the \(2T\) period represents the main instability area of the members, which can be assumed by the form of trigonometric series written as Eq. (14),

where \(\left\{ {a_{k} } \right\}\) and \(\left\{ {b_{k} } \right\}\) are the constant coefficients.

Substituting Eqs. (13) and (14) into Eq. (12), we have,

And using trigonometric convert formulas, we have

Substituting Eqs. (16) and (15) and classifying the \({\text{sin}}()\) and \({\text{cos}}()\) terms, it yields,

By separating the coefficients of \(sin\frac{{k{\Omega t}}}{2}\) and \(cos\frac{{k{\Omega t}}}{2}\) and converting them into matrix form, the following expressions about \(a_{k}\) and \(b_{k}\) can be obtained,

Here, we force on the primally instability region. Then, we take the first-order determinant and let the coefficients of \(sin\frac{{{\Omega t}}}{2}\) and \(cos\frac{{{\Omega t}}}{2}\) be zero, it yields,

The dynamic instability areas corresponding to different values A and B can be calculated by Eq. (20).

The dynamic instability regions can be calculated using following equation,

The dynamic instability regions \(\frac{{{\Omega }^{2} }}{4}\) can be obtained by substituting Eqs. (6), (8), (10) or (7), (9), (11) into Eq. (21).

Solutions for free vibration and static instability

Here we focus on the behavior of vibration and static and dynamic stability of thin-walled structures. Equation (12) can be converted into eigenvalue equations corresponding to different problems. The frequency or buckling stress are given by solving the corresponding eigenvalue problem.

For the free vibration, the structure endures no external loads, so Eq. (12) with \(\lambda\)=0 can be rewritten as

The frequency can be calculated as follows

The natural frequency \(\omega\) can be obtained by substituting Eqs. (6) and (8) or (7) and (9) into Eq. (23).

For the static stability of the structure under static load, the mass matrix is omitted since structural inertial effect is not considered and \({\lambda }_{t}\)=0, and Eq. (12) can be transformed as follows,

The buckling of the RR and RF plate can be analyzed as follows,

The critical buckling load \(\lambda_{cr}\) can be obtained by substituting Eqs. (8), (10) or (9), (11) into Eq. (25).

Results of validated models

In this section, several examples are adopted and theoretical solutions and numerical results are compared to validate the accuracy of the presented model. Box, I, and C section, as shown in Fig. 1, are selected to validate the free vibration frequency and the critical stress obtained by presented model and FEM, respectively. The section dimensions of the members are shown in Table 1, where bw, b = bf, δ, L are the web height, flange width, thickness, and whole length, respectively. Taking graphite epoxy laminated material as an example, the material properties are \(\rho = 1600 \times 10^{ - 12} {\text{t}}/{\text{mm}}^{3}\), E1 = 185,000 MPa, E2 = \(10,5000\) MPa, \(\nu_{12}\) = 0.28, \(\nu_{21}\) = 0.01589, G12 = 7300 \({\text{MPa}}\).

The numerical model was modeled using shell elements in ABAQUS software. The ratio of the length of the element to the length of the member is 0.01. The type of element is S4R. As described in Table 1, it is observed that the analytical results are in good agreement with FEM. The difference in the results is due to the fact that there are still slight differences between the plate deformation depicted by the subdivided mesh in the numerical model and the deformation function constructed by trigonometric series and interpolation functions in this work.

The second comparative example is obtained from the results of Vo and Lee13 based on the shear beam theory. The geometric parameters of the symmetrical angle I section beam with a length of L = 1000 mm are taken as bw = bf = 50 mm, δ = 2.08 mm. The material parameters of glass epoxy resin material are E11 = 53.78 GPa, E22 = 17.93 GPa, G12 = G13 = 8.96 GPa, G23 = 3.45 GPa, v12 = 0.25, and ρ = 1968.93 kg/m3. Table 2 shows the comparison of the first two vibration modes of the members. It can be found that the results of the model are in good agreement with the existing results.

In the third comparative example, we consider the buckling of a composite I cross-section. The material properties are given in Table 3.a and b are tensile elastic modulus and compressive elastic modulus, respectively. The critical load predicted by the present model is compared with the experimental results obtained by Liu et al.13. As shown in Table 4, the results of the present model are found to be consistent with the experimental results.

Results and discussion

After verifying the accuracy of the model, several cases are carried out to evaluate the effects of geometric parameters and loading scenarios on the vibration, static, and dynamic buckling of members with box, C, and I sections.

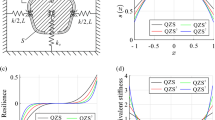

Interaction between plates of section

Before static and dynamic analysis of TWS, the mutual restraint effects between plates are discussed. Here, comparison is conducted through CUFSM, which was developed based on the finite strip method (FSM). Due to the use of discrete elements along the plate width, FSM can better consider the interactions between plates. Here, some cold-formed thin-walled steel sections that are commonly used in engineering are selected. The selected length of the members is from 30 to 1000mm, and the material properties are \(\rho = 7850 \times 10^{ - 12} t/{\text{mm}}^{3}\), E = 210,000 MPa, \(\nu\) = 0.3, G = 80,769 MP\(80769{\text{MPa}}\). Unless otherwise specified, those material parameters will be used for the subsequent parametric analysis. The results of the comparison between the model and CUFSM are shown in Fig. 2 and observation shows that the model agrees well with CUFSM in the area where local buckling occurs. As the member length increases, the difference between the model results and CUFSM results becomes larger, which can be attributed to that member become more susceptible to global buckling as their length increases, and global buckling is dominated by rigid deformation of the entire section rather than local plate deformation. Therefore, the interaction between plates has little influence on the global buckling.

Critical buckling load for the member with different lengths; The static critical stresses are predicted by Eq. (25).

Since the bending stiffness of each plate in the cross-section is different, the sequence of plate buckling may be different. Here, we studied the situation where the web or flange buckled first and gave the corresponding restraint stiffness in the supplementary material. The plate that buckles first is constrained by the plate that buckles later. Then, the box-, C- and I-sections of cold-formed steel are selected to calculate the spring restraint stiffness when the web or the flange buckles first, respectively. kf-w represents the restraining stiffness provided by the flange to the web when the web buckles first, and kw-f represents the restraining stiffness provided by the web to the flange when the flange buckles first. As shown in Fig. 3, when the web buckles first, the restraint stiffness provided by the flange (kf-w) increases significantly with the increment of the flange width. When the flange buckles first, with the increase of the flange width, the web’s restraining effect on the flange first increases and then tends to be stable. When the width of the flange is small, the restraint effect of the web on the flange is obvious, indicating that the web significantly limits the rotation of the flange. It is found that for the case with box-section, when bf/h = 1, the mutual restraint effect between the web and the flange is equal. However, for C- and I-sections, when bf/h = 1, the mutual restraint effects of the web and the flange are not equal, which can be attributed to the fact that the boundary conditions of flange are that one end is bound and the other is free. In fact, the ratio of each plate in the open-section or closed-section is within a certain range. In the subsequent parametric analysis, we selected the common section size to expand the analysis.

Spring stiffness of CFS sections; The restraint stiffnesses obtained from Appendix A.

Furthermore, the influence of the auxetic effect on the plate restraint are also discussed here. The material parameters of the thin laminated plate structure are shown in Table 5. Case A and Case B represent auxetic and traditional materials, respectively.

The rotational restraint stiffness of three types of TWS are calculated, as shown in Fig. 4. The tendency of rotational restraint provided by the web or the flange is similar to that of the isotropic TWS, that is, the value of kf-w increases with the increase of flange width, as shown by the bule line in Fig. 4a1,b1,c1. While, the restraint stiffness of the web to the flange (kw-f) decreases first as the flange width bf increases, and then becomes stable after passing the position where the stiffness is equal, see red lines in Fig. 4a1,b1,c1. The auxetic effect increases the value of two types stiffness of the box sections by the same amount. For opened-sections, such as C and I sections, the auxetic effect significantly enhances the restraining effect of the flange on the web, as shown in Fig. 4b2,c2.

Vibration and instability behaviors of cold formed steel members

In the previous section, the interaction between plates was discussed by taking buckling studies as an example. As shown in Fig. 2, it is seen that the critical stresses show a trend of decreasing and then increasing as the member length increases, and the smallest buckling value can be considered for engineering design. In addition, the vibration and dynamic buckling responses of the components are discussed here. The effect of geometric dimension on the frequencies are depicted by Fig. 5. As expected, the frequency of the members decrease significantly as the length increases. Subsequently, the critical length is determined according to Fig. 2, which corresponds to the minimum critical stress. It is important to note that the temperature field is not considered here. Previous studies have shown that the temperature field can cause large initial deformations of members with a large coefficient of thermal expansion, which affects their vibration frequency32.

Effect of length on the free vibration; The frequencies are predicted by Eq. (23).

The ideal periodic load for this work is adopted. For the study of the dynamic instability behavior of structures under random dynamic loads such as earthquakes can be found in exciting works33,34,35. The first-order dynamic instability area is given in Fig. 6. It is observed that as the coefficient α increases, the dynamic instability region moves to the left, which means that the instability frequency decreases. Also, different aspect ratios of components show different sensitivities to changes in static load coefficients.

Dynamic buckling frequency of CFS sections; The dynamic buckling frequencies are predicted by Eq. (21).

Vibration and instability behaviors of laminated structures

Here, the static and dynamic responses of thin-walled laminates are also studied. Two cases are adopted as given in Table 5. The effect of auxetic property on the vibration and instability are depicted by Figs. 7 and 8, respectively. This observation shows that the auxetic effect on the critical frequency of the members is not obvious. The auxetic effect has different effects on the critical stress of the TWS with box, C-, and I-sections at different half-wavelengths. For structures with local deformation caused by impact contact, the auxetic effect can significantly reduce the local indentation36.

The dynamic instability regions of the laminated thin-walled structure are further shown in Fig. 9, in which static and dynamic coefficients (α, β) are taken as variables. The comparison results show that with the increase of the static coefficient α, the instability area moves to the left, indicating that the dynamic instability frequency decreases. Meanwhile, comparing case A and case B, it can be found that the auxetic effect can reduce the dynamic instability frequency of the Box-section but increase the frequency of the C- and I- sections. The auxetic effect has little influence on the area of the unstable region. In addition, the effect of density on dynamic instability is also considered. A thin-walled C section with 160–60–3.0–60(mm) is adopted. As shown in Fig. 9b, the density is taken as 1800kg/m3, 2000kg/m3, and 2200kg/m3. It can be observed that the dynamic instability frequency decreases with the increase of density.

Conclusion

In this work, static and dynamic analyses of TWS with open- and closed-sections are carried out based on classical plate theory. A spring plate model is proposed to equate the cross-section composed of multiple plates to a single plate with constraints. The spring constraint stiffness is derived to consider the mutual constraint effects between plates. Based on the energy method, the analytical solution of vibration and static buckling of thin-walled components are given. Subsequently, the analytical solution to the dynamic instability of the component is derived based on the Bolotin method. Cold-formed thin-walled steel and composite laminated structures are selected for parametric analysis. The conclusions are summarized as follows:

-

The restraint effect of adjacent plates cannot be ignored. Accurate restraints are the key to characterizing the interaction between plates. A spring plate models with restrained boundary conditions can accurately predict the global vibration and instability behavior of members.

-

The mutual restraint relationship between plates significantly affects the global mechanical behavior of the members. As the plate width ratio changes, the relationship between the restraint and the restrained will changes, thus determine the vibration or buckling mode of the member.

-

The mutual restraint rules between isotropic or orthotropic plates are similar. The constraint stiffness of plate depends on both the material properties and the geometry of the plate.

-

Different cross-section forms show different sensitivities to the auxetic effect. The auxetic influence not only have positive but have negative effects on the vibration and instability behaviors of structures. This positive or negative effect depends on the size ratio of the cross-section.

The model in this work is still limited to perfect members. In fact, there may be global or local damage to the components during production and service. For example, damage such as local fiber cracks or delamination in composite laminated structures. In future work, we will consider the effects of global defects and local damage on the restraint effect of the plate as well as the vibration and buckling behavior of the structure. In addition, the influence of structural damping effect on mechanical behavior is also a future research direction.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shen, G. Mechanics of Composite Materials (Tsinghua University Press, 1996).

Zuo, H. et al. Analysis of laminated composite plates using wavelet finite element method and higher-order plate theory. Compos. Struct. 131, 248–258 (2015).

Shen, C. et al. Determining the critical buckling load of locally stiffened U-shaped steel sheet pile using dynamic correlation coefficient method. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 12970 (2022).

Hussein, A. B. Structural behaviour of built-up I-shaped CFS columns. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 25628 (2024).

He, Z. et al. Design recommendation of cold-formed steel built-up sections under concentric and eccentric compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 212, 108255 (2024).

Zhu, J., Qian, S. & Li, L. Dynamic instability of laterally-restrained zed-purlin beams under uplift loading. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 131–132, 408–413 (2017).

Aydin, E. et al. Optimization of elastic spring supports for cantilever beams. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 62(1), 55–81 (2020).

Aydın, E., Kebeli, Y. E. & Çetin, H. Design of visco-elastic supports for Timoshenko cantilever beams. Konya J. Eng. Sci. 11, 1–22 (2023).

Nguyen, T., Kim, N. & Lee, J. Free vibration of thin-walled functionally graded open-section beams. Compos. B Eng. 95, 105–116 (2016).

Sheikh, A. H. & Asadi, A. Vibration of thin-walled laminated composite beams having open and closed sections. Compos. Struct. 134, 209–215 (2015).

Arpaci, A. & Bozdag, E. On free vibration analysis of thin-walled beams with nonsymmetrical open cross-sections. Comput. Struct. 80(7), 691–695 (2002).

Kollar, L. P. Flexural–torsional vibration of open section composite beams with shear deformation. Int. J. Solids Struct. 38(42), 7543–7558 (2001).

Vo, T. P. & Lee, J. Flexural–torsional coupled vibration and buckling of thin-walled open section composite beams using shear-deformable beam theory. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 51(9–10), 631–641 (2009).

Wu, J. S. & Luo, S. S. Use of the analytical-and-numerical-combined method in the free vibration analysis of a rectangular plate with any number of point masses and translational springs. J. Sound Vib. 200(2), 179–194 (1997).

Watkins, R. J. & Barton, O. Characterizing the vibration of an elastically point supported rectangular plate using Eigen sensitivity analysis. Thin-Walled Struct. 48(4–5), 327–333 (2010).

Eisenberger, M. & Deutsch, A. Static analysis for exact vibration analysis of clamped plates. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 15(08), 1540030 (2015).

Higginson, K. et al. Local buckling of FRP thin-walled plates, shells and hollow sections with curved edges and arbitrary lamination. Thin-Walled Struct. 168, 108242 (2021).

Debski, H. et al. Local buckling, post-buckling and collapse of thin-walled channel section composite columns subjected to quasi-static compression. Compos. Struct. 136, 593–601 (2016).

Liu, T., Vieira, J. D. & Harries, K. A. Predicting flange local buckling capacity of pultruded GFRP I-sections subject to flexure. J. Compos. Constr. 24(4), 04020025 (2020).

Kollar, L. P. Buckling of unidirectionally loaded composite plates with one free and one rotationally restrained unloaded edge. J. Struct. Eng. (New York, N.Y.) 128(9), 1202–1211 (2002).

Tenenbaum, J. & Eisenberger, M. Analytic solution of rectangular plate buckling with rotationally restrained and free edges. Thin-Walled Struct. 157, 106979 (2020).

Shabanijafroudi, N., Jazouli, S. & Ganesan, R. Effect of rotational restraints on the stability of curved composite panels under shear loading. Acta Mech. 231(5), 1805–1820 (2020).

Qiao, P. & Shan, L. Explicit local buckling analysis and design of fiber–reinforced plastic composite structural shapes. Compos. Struct. 70(4), 468–483 (2005).

Bolotin, V. V. The Dynamic Stability of Elastic Systems (Holden-Day, 1964).

Zhu, J., Qian, S. & Li, L. Dynamic instability of channel-section beams under periodic loading. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 27(10), 840–849 (2020).

Wu, M. et al. Dynamic instability and free vibration analysis of thin-walled structures with arbitrary cross-sections. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137(3), 1–14 (2022).

Huang, S. & Qiao, P. Buckling of partially-compressed laminated composite plates. Thin-Walled Struct. 169, 108385 (2021).

Patel, S. N., Datta, P. K. & Sheikh, A. H. Buckling and dynamic instability analysis of stiffened shell panels. Thin-Walled Struct. 44(3), 321–333 (2006).

Lyapunov, A. M. The general problem of the stability of motion. Int. J. Control 55, 531–531 (1992).

Mascolo, I. Recent developments in the dynamic stability of elastic structures. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 5, 51 (2019).

Wu, M. et al. Auxetic effects in the large deflection bending characteristics of FG GRMMC shallow arches. Appl. Math. Model. 119, 534–548 (2023).

Wu, M. et al. Thermal buckling and vibration analysis of cold-formed steel sections. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 32, 101910 (2022).

Li, J. & Xu, J. Dynamic stability and failure probability analysis of dome structures under stochastic seismic excitation. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 14, 1440001 (2014).

Nair, D. et al. Higher mode effects of multistorey substructures on the seismic response of double-layered steel gridshell domes. Eng. Struct. 243, 112677 (2021).

Bysiec, D. & Maleska, T. Influence of the mesh structure of geodesic domes on their seismic response in applied directions. Arch. Civ. Eng. 69, 65–78 (2023).

Wu, M. et al. A novel oblique impact model for elastic solids. Int. J. Impact Eng 180, 104699 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial supports received from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12102214, No.11972203, No.11572162), Ningbo Key Technology Breakthrough Plan Project of "Science and Technology Innovation Yongjiang2035"(2024Z256), the Science and Technology Innovation 2025 Major Project of Ningbo City (Grant No. 2022Z209), and the Ningbo Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No.2022J128,2022J090). Ningbo Special Equipment Inspection Institute, and K.C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University. This research was funded by the Special research funding from the Marine Biotechnology and Marine Engineering Discipline Group in Ningbo University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Meng-Jing Wu wrote the main content of the manuscript. Jue Zhu and Xu-Hao Huang participated in and supervised the writing of the manuscript. All authors made revisions to the draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, MJ., Zhu, J. & Huang, XH. An analytical solution for dynamic instability and vibration analysis of structural members with open and closed sections. Sci Rep 15, 5152 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85708-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85708-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

A Review of Advanced Modeling Methods for Thin-Walled Beams: From Deductive Methods to Data-Driven Approaches

Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering (2026)

-

Axial strength of back to back cold formed steel short channel sections with unstiffened and stiffened web holes

Scientific Reports (2025)