Abstract

Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) may exhibit poorer performance in visuomotor tasks than healthy individuals, particularly under conditions with high cognitive load. Few studies have examined reaching movements in MCI and did so without assessing susceptibility to distractor interference. This proof-of-concept study analyzed the kinematics of visually guided reaching movements towards a target dot placed along the participants’ midsagittal/reaching axis. Movements were performed with and without a visual distractor (flanker) at various distances from the reaching axis. Participants were instructed to avoid “touching” the flanker during movement execution. The whole sample included 11 patients with MCI due to Alzheimer’s disease, 10 healthy older adults, and 12 healthy young adults, all right-handed. Patients with MCI performed reaching movements whose trajectories deviated significantly away from the flanker, especially when it was 1 mm away, with less consistent trajectories than controls. Also, our results suggest that trajectory curvature may discriminate between patients with MCI and healthy older adults. The analysis of reaching movements under conditions of visual interference may enhance the diagnosis of MCI, underscoring the need for multidimensional assessments incorporating both cognitive and motor domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is traditionally regarded as an intermediate stage between normal aging and frank dementia1. However, some individuals with MCI may remain stable over time2 or revert to normal cognition3. Several neuropsychological features can refine MCI diagnosis and provide prognostic insights. These encompass the clinical phenotype4,5, sensitivity to cueing or recognition in memory tasks5, anosognosia for memory deficits6, neuropsychiatric symptoms7, and sleep disorders8. Nevertheless, the pathophysiological diagnosis remains crucial for prognosis9. Recognizing this important issue and anticipating our conclusions, this proof-of-concept study proposes a novel paradigm to support the early detection of MCI due to Alzheimer’s Disease (AD).

The emphasis on higher-order cognitive functions in the study of MCI has likely overshadowed a crucial aspect: the motor function. Activities such as grasping, jumping, navigating obstacles, or engaging in creative tasks like drawing, embroidery, and origami construction involve complex and integrated cognitive processes. Only recently has motor function received increasing attention within the MCI framework. Many studies have concentrated on lower extremity motor function, including muscle strength, gait speed, postural control, balance, and functional mobility10. This focus is justified. Impairments in lower extremity motor function can predict a loss of autonomy in activities like walking, driving, or using public transportation, even in healthy aging11. However, it is surprising that only a few studies have explored the visuomotor function in MCI. Here we define the visuomotor function as the integration of distinct neurocognitive domains for planning and executing unimanual or bimanual movements, encompassing fine and gross motor skills performed under perceptual control.

Healthy aging is consistently associated with a decline in visuomotor function. Such a decline is multifactorial, influenced by physiological, lifestyle, and cognitive factors12. Similar to lower extremity motor dysfunctions, visuomotor deficits can be highly debilitating in the elderly population, affecting activities of daily living such as eating, dressing, cooking, doing household chores, and maintaining personal hygiene13. These findings underscore the importance of assessing visuomotor performance in MCI, especially given the nosographic significance of functional dependency. In fact, this represents one of the delicate demarcation lines between MCI and early dementia.

Different paradigms, such as visuomotor transformation, finger-tapping, handwriting, or pegboard tests, have been used to assess visuomotor function in MCI (see Ilardi et al.14 for a review). This methodological heterogeneity complicates the efforts to draw comprehensive conclusions about visuomotor deficits in MCI. However, these patients appear to manifest visuomotor difficulties before the onset of clear apraxia, ataxia, or severe neurological phenomena typically encountered in the advanced stages of dementia. Intriguingly, the severity of these impairments can be similar to that observed in patients with full-blown dementia.

A quantitative kinematic analysis of simple, visually guided reaching movements may serve as a valuable neuropsychological index of visuomotor function. Conventional assessments, such as the finger tapping and pegboard test, offer rudimentary estimates based on the number of motor responses within a specific time frame. Conversely, a fine-grained analysis of reaching movements may be more clinically sound, as these movements are computed at the cortical level in the posteromedial parietal lobe15. While AD-related neurodegenerations in this brain region are commonly associated with amnestic MCI phenotypes2,4,9, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying visuomotor impairment in MCI remain largely elusive. A leading hypothesis suggests a breakdown of functional connectivity within the frontoparietal network16,17. Recent research on healthy individuals has consistently identified shared and domain-specific cortical areas for decoding kinematic parameters of reaching movements from source activity in magnetoencephalography (MEG) data. These encompass the frontoparietal network, where the posterior parietal cortex plays a pivotal role in sensorimotor integration18. Another hypothesis pertains to periventricular and/or subependymal lesions affecting the frontal lobe19, along with subcortical accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles20. Additionally, impairment of the pulvinar has been proposed as a contributing factor to visuomotor deficits in MCI21. The pulvinar, in concert with the occipitoparietal cortex and superior colliculus, is engaged in a wide range of neurocognitive processes crucial for executing visuomotor tasks. These processes include visual search, selective attention, color and form recognition, multisensory integration, eye-hand movements, and interference inhibition during movement execution22.

So far, only a few studies have analyzed reaching movements in patients with MCI23,24,25. These studies included patients with AD, patients with amnestic MCI, and healthy controls. For instance, Camarda et al. designed an experiment where participants were instructed to reach out and touch one of the six flat LEDs positioned on a table using their right index finger as quickly and accurately as possible. The LEDs could be positioned at two distances from the starting position (15 cm and 30 cm) across three distinct spatial locations: along the midsagittal plane or laterally, at 60° to the right and 60° to the left relative to the midsagittal plane. When one of the six LEDs turned on, participants were required to touch the target LED. The results showed that patients with AD exhibited significantly slower reaching movements compared with patients with MCI and healthy controls. No significant differences were observed between MCI and control participants23. Still, in the study by Yan et al., participants were asked to alternatively reach two target dots on a digitizer using a stylus held in their dominant hand. Patients with MCI demonstrated faster and more consistent movements than patients with AD, though both groups were slower and less consistent than the control group25. Finally, Mitchell et al. required participants to perform reaching movements towards lateral/peripheral (non-foveated) target objects using their index fingers without shifting their gaze from a fixation point, or under free visual guidance (control condition). The stimuli were white circles with a 2° diameter presented on a touchscreen. While no main effect of the experimental manipulation was detected, this study found that patients with AD showed longer movement times than those with MCI, with both patient groups being slower than the control group24. Given this snapshot of the available literature, the current understanding of reaching movement kinematics in the MCI population is ambiguous. Such an ambiguity is exacerbated by the diverse experimental procedures employed, in addition to inclusion criteria restricted to clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, the above studies assessed reaching movements under ideal and poorly ecological conditions, that is, in the absence of distractors.

Reaching for an object requires the dynamic, perceptual-based localization of the spatial position of the target object in relation to the effector. Also, engrams that incapsulate expectations about the sensory outcomes of movement, as well as invariant visuospatial and mechanical features of the target object, are essential26,27. Moreover, in daily life, the visual environment often includes both relevant and irrelevant objects to the movement. Irrelevant objects may act as distractors, diverting attentional focus and potentially interfering with movement trajectory and speed. Previous evidence has suggested an increased susceptibility to distractor interference in the elderly population28,29. Whether this susceptibility is heightened in patients with MCI and affects visuomotor function remains unexplored thus far.

In previous research, patients with MCI were asked to perform basic transportation movements towards a target object. In contrast, we designed a paradigm where participants reach for a target in the presence of non-target, to-be-ignored objects (i.e., distractors). The goal was to explore specific components of visuomotor control, such as attentional filtering and inhibitory processes. The limited capacity of visual attention may hinder visuomotor function, disrupting the movement planning phase when filtering out non-target information30,31. Moreover, distractors can compete with the target for the control of action, particularly under dual-task demands32,33,34. According to the load theory of attention, rapid task shifts (e.g., ignoring a distractor before reaching the target) can heighten distractor-related interference35. To explore these phenomena, our participants were instructed to reach for the target while avoiding “collisions” with the distractor. Furthermore, distractors were located halfway between the starting point and the target object. This spatial arrangement is expected to elicit stronger competing responses and affect visuomotor control29,36. Finally, we used significantly larger distracting stimuli than the target, as the inhibition required to counteract the influence of distractors depends on their salience32,37. The position of distractors varied slightly from trial to trial to make them more or less obstructive during the movement. However, spatial configurations were designed to make the interference effect unpredictable at movement initiation. This enabled the assessment of mid-course trajectory adjustments needed to maintain accuracy38.

As a whole, the present proof-of-concept study explored whether visuomotor performance is affected by distractor interference in patients with MCI. We hypothesized that patients would show reduced visuomotor performance, especially under highly distracting conditions. Although this relationship has been observed in healthy individuals, research on sensorimotor integration has suggested that visuomotor deficits further deteriorate along the dementia spectrum as cognitive load increases17,39. Also, we anticipate that our visuomotor paradigm might be effective for the early identification of MCI.

Results

A priori power analysis for mixed design

G*Power 3.1.9.7 was employed to conduct an a priori power analysis for mixed ANOVA. Setting α = 0.05, statistical power (1-β) = 0.80, assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), and accounting for 3 groups and within-subject measurements ranging from 4 to 12 (for speed and lateral deviations, respectively), the estimated total sample size needed ranged between 18 and 30 units.

Descriptive statistics

Fifteen eligible patients were examined, 4 of which were removed from the dataset as they later received diagnoses of non-amnestic MCI (n = 2), frontal variant of AD (n = 1), and mild-stage AD (n = 1). Therefore, data from 11 patients with amnestic MCI due to AD (5 females; M age = 72.18 years, SD = 6.90, age range = 60–78 years; M education = 12.55 years, SD = 4.32, education range = 5–18 years) were analyzed. The two control groups consisted of 10 healthy older adults (HOA, 4 females; M age = 67.00 years, SD = 5.92, age range = 60–78 years; M education = 12.40 years, SD = 4.19, education range = 5–17 years) and 12 healthy young adults (HYA, 5 females; M age = 29.92 years, SD = 3.20, age range = 25–35 years; M education = 18.08 years, SD = 0.90, education range = 16–20 years), respectively. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for demographic and neuropsychological variables. Patient and control groups were matched for sex (χ2 = 0.442, df = 2, p > 0.05). Compared to HOA, patients with MCI did not differ in either age or education (all pbonf > 0.05). However, HYA were more educated than both HOA (M diff. = 5.683, pbonf = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 1.65) and patients with MCI (M diff. = 5.538, pbonf = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 1.61). Since education may play a significant role in refining visuomotor abilities40, this variable was included as a covariate in mixed ANOVA models. Descriptive statistics of the kinematic data are reported in Table 2.

Right-handed reaching movements

Constant lateral deviation

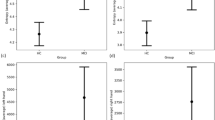

No significant main effect of group was detected (F(2, 29) = 2.467, p > 0.05). However, a main effect of condition (F(2, 70) = 11.568, p < 0.001, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.32) and a condition × distance × group interaction effect (F(6, 88) = 2.954, p = 0.014, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.19) were found. Specifically, movement trajectories exhibited a significant rightward deviation in the presence of the flankers compared to the control condition (Flanker 1 mm vs. control: M diff. = 1.416, 95% CI [1.141, 1.692], SE = 0.102, t = 13.921, Cohen’s d = 1.87; Flanker 3 mm vs. control: M diff. = 0.764, 95% CI [0.488, 1.039], SE = 0.102, t = 7.506, Cohen’s d = 1.00; Flanker 5 mm vs. control: M diff. = 0.471, 95% CI [0.195, 0.747], SE = 0.102, t = 4.629, Cohen’s d = 0.62, all pbonf < 0.001). Furthermore, the closer the flanker was to the reaching axis, the greater the lateral deviation to the right (Flanker 1 mm vs. Flanker 3 mm: M diff. = 0.653, 95% CI [0.377, 0.928], SE = 0.102, t = 6.415, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.86; Flanker 1 mm vs. Flanker 5 mm: M diff. = 0.945, 95% CI [0.670, 1.221], SE = 0.102, t = 9.292, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.25; Flanker 3 mm vs. Flanker 5 mm: M diff. = 0.293, 95% CI [0.017, 0.568], SE = 0.102, t = 2.877, pbonf = 0.031, Cohen’s d = 0.39). As for the interaction effect, trajectories showed a greater rightward deviation at distances of 50 mm (M diff. = 1.453 [0.539, 2.366], SE = 0.223, t = 6.513, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.92) and 90 mm (M diff. = 1.842 [0.928, 2.755], SE = 0.233, t = 8.258, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.43) compared to trajectories recorded at 20 mm. No difference in constant lateral deviation (CLD) was found between 90 and 50 mm distances (M diff. = 0.389, pbonf > 0.05). Interestingly, the interaction between distance and condition was present in the Flanker 1 mm condition only, and notably, it was specific of the patient group (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

Line graphs depicting the relationship between constant lateral deviation (CLD, x-axis) and distance (y-axis) in the right hand block for each group. The 0 value on the x-axis corresponds to midsagittal/reaching axis. Positive values indicate rightward movements; negative values indicate leftward movements. Error bars represent standard errors. Note: MCI mild cognitive impairment, HOA healthy older adults, HYA healthy young adults.

Examples of manual pointing trajectories under flanker conditions from randomly selected subsamples of healthy young adults (HYA, n = 3), healthy older adults (HOA, n = 3), and patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI, n = 4). The x-axis represents the constant lateral deviation (CLD), where a value of 0 represents the reaching axis. Positive values indicate rightward deviations, while negative values indicate leftward deviations. The graph was generated using MATLAB R2024b.

Variable lateral deviation

No significant main effects of condition (F(2, 51) = 2.207, p > 0.05) or distance (F(1, 41) = 2.185, p > 0.05) were found. However, the model highlighted a significant main effect of group (F(2, 29) = 4.887, p = 0.016, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.28) and a distance × group interaction effect on movement consistency (F(3, 42) = 3.520, p = 0.024, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.22). Post-hoc analysis revealed that the variable lateral deviation (VLD) increased from 20 to 90 mm across all three groups, irrespective of condition. However, patients with MCI demonstrated a heightened dispersion of trajectories (HYA: M diff. = 0.362, 95% CI [0.071, 0.654], SE = 0.086, t = 4.206, pbonf = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.81; HOA, M diff. = 0.511, 95% CI [0.229, 0.794], SE = 0.083, t = 6.136, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.14; MCI: M diff. = 0.757, 95% CI [0.509, 1.005], SE = 0.073, t = 10.333, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.69).

Movement speed

Neither a main effect of group (F(2, 29) = 1.089, p > 0.05) nor condition (F(1, 31) = 0.176, p > 0.05) emerged. Nonetheless, a significant condition × group interaction effect was found (F(2, 31) = 4.222, p = 0.021, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.24). More precisely, while HYA maintained a constant mean velocity during reaching movements across all conditions (all pbonf > 0.05), both HOA and patients with MCI were faster in control trials than in trials where the reaching axis was flanked by a visual distractor (HOA × Flanker 1 mm: M diff. = 4.971, 95% CI [2.187, 7.756], SE = 0.794, t = 6.260, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.90; HOA × Flanker 3 mm: M diff. = 4.510, 95% CI [1.726, 7.294], SE = 0.794, t = 5.679, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.72; HOA × Flanker 5 mm: M diff. = 4.285, 95% CI [1.500, 7.069], SE = 0.794, t = 5.395, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.64; MCI × Flanker 1 mm: M diff. = 3.810, 95% CI [1.371, 6.248], SE = 0.696, t = 5.477, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.45; MCI × Flanker 3 mm: M diff. = 3.839, 95% CI [1.400, 6.277], SE = 0.696, t = 5.519, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.47; MCI × Flanker 5 mm: M diff. = 3.603, 95% CI [1.164, 6.041], SE = 0.696, t = 5.180, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.37). No effect of the flanker position was detected.

Left-handed reaching movements

Constant lateral deviation

The model did not show any main effects of group (F(2, 29) = 0.679, p > 0.05), condition (F(2, 46) = 0.269, p > 0.05), or distance (F(1, 33) = 0.567, p > 0.05), nor did it reveal any significant interaction effects.

Variable lateral deviation

No effects of group (F(2, 29) = 1.382, p > 0.05) or condition (F(2, 69) = 0.723, p > 0.05) were detected on the VLD, and no interaction effects were observed. However, a main effect of distance was found (F(2, 58) = 8.307, p < 0.001, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.25), with participants showing increased trajectory variability from 20 to 90 mm (M diff. = -0.448, 95% CI [-0.587, -0.309], SE = 0.056, t = -7.968, pbonf < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.63).

Movement speed

No group (F(2, 29) = 0.352, p > 0.05), condition (F(1, 35) = 0.102, p > 0.05), or condition by group interaction effects (F(2, 35) = 1.816, p > 0.05) were observed.

Aligned rank transform procedure nested into linear mixed models

Although the parametric analysis of the raw data provided convincing results, the small sample size and the unsatisfied independence assumption (considering the quasi-experimental, i.e., groups are formed ex post facto, repeated measures design) suggested the need for an alternative approach to corroborate our findings. Accordingly, an Aligned Rank Transformation (ART), combined with a Linear Mixed-Effects Model (LMM), was performed. ART acts as a preliminary step to allow parametric statistical models to work with non-parametric distributions. For each possible main effect and interaction, data are preprocessed stripping from the dependent variable all effects but the one for which alignment is being performed. Once aligned, the data are ranked, with averages applied in cases of ties. ART ensures that main effects and interactions have appropriate Type I error rates and suitable power. ARTool.exe version 2.2.241 was used to generate aligned and ranked responses for CLD in the right-hand condition. Therefore, an LMM was carried out. In this context, LMMs were preferred over traditional ANOVA models as they do not assume independent observations and are then better suited for repeated measures observations42. Here, LMMs incorporated fixed effects for group, condition, distance, and education (as a covariate), while participant ID was modeled as a random effect. The Satterthwaite method was used to approximate degrees of freedom for fixed effects. Post-hoc pairwise contrasts were conducted using the ART-C procedure43, with Bonferroni’s correction applied for multiple comparisons. Overall, the results are consistent with those detected by the raw data model and further supported by a significant main effect of group (F(2, 25) = 7.338, p = 0.003). Specifically, when keeping the within-subject factor levels constant, CLDs were found to be larger in patients with MCI compared to both HYA (pbonf = 0.017) and HOA (pbonf = 0.013). Additionally, a significant condition × distance × group interaction effect was confirmed (F(12, 286) = 2.984, p < 0.001). In the control condition, participants showed no significant deviations in their trajectories. Compared to the control condition, they exhibited a significant rightward deviation at 20, 50, and 90 mm from the starting dot across all flanker conditions, with CLD values increasing as the flanker approached the reaching axis (all pbonf ≤ 0.007). The only exception was the Flanker 5 mm condition, where CLDs at 90 mm did not significantly differ from the control condition (pbonf = 0.100). Under all conditions, there was no observed difference in trajectory at 20 mm, both within and between subjects. Within experimental conditions, healthy participants showed no significant deviations from 20 to 90 mm, except for HOA in the Flanker 1 mm condition, where they displayed a pronounced CLD only from 20 to 90 mm (pbonf < 0.001). Patients with MCI deviated outward from 20 to 50 mm in all flanker conditions (pbonf ≤ 0.005), and maintained these outward trajectories from 50 to 90 mm. However, in the Flanker 5 mm condition, CLDs at 90 mm did not differ from the control condition. This suggests an apparent “returning” trajectory, with patients tending to realign with the reaching axis as they approached the flanker (see Fig. 1).

Receiving operating characteristic curve analysis

Based on the above analysis results and theoretically speaking, the constant lateral deviation at a distance of 50 mm in the Flanker 1 mm condition, recorded within the right-hand block, was identified as the most discriminative kinematic parameter. Therefore, we further assessed its diagnostic power using nonparametric receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Also, we compared its discriminative capability to that of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)44, a widely recognized cognitive assessment tool in clinical neuropsychology. An area under the ROC curve (AUC) between 0.70 and 0.80 was considered adequate45. The optimal cutoff score was determined using the Youden (J) index, calculated as sensitivity + specificity – 146. Also, additional diagnostic metrics, including positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV), false positive and false negative rates (FPR and FNR), overall accuracy (ACC), and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR + and LR-) were calculated47. Statistical analyses were conducted using the pROC R package. The nonparametric bootstrap method implemented in R was employed to compute the 95% confidence intervals for AUCs. The DeLong test was used to compare the AUCs48. In the classification model, the state variable was a dummy variable, with HOA coded as 0 and patients with MCI as 1. Although underpowered (given a nominal α = 0.05, 1–β = 0.80, expected AUC = 0.70, and allocation ratio = 1, there was a shortfall of 27 sample units49), our preliminary results showed that both the raw MMSE score—as expected—and the CLD demonstrated good classification capability (MMSE: AUC = 0.864, 95% CI [0.697, 1.000], SE = 0.077, p < 0.001; CLD: AUC = 0.822, 95% CI [0.624, 1.000], SE = 0.096, p < 0.001). No significant difference was detected between the two AUCs (DeLong test, p = 0.888; see Fig. 3). With a J of 0.59, the optimal cutoff point for distinguishing between HOA and patients with MCI via CLD was 1.79 mm. This cut-point exhibited promising diagnostic properties (sensitivity = 0.70, specificity = 0.89, FPR = 0.11, FNR = 0.30, PPV = 0.87, NPV = 0.72, ACC = 0.79; LR + = 6.30, LR- = 0.34).

Relationship between constant lateral deviation and cognitive functioning

A Spearman correlation analysis with 1,000 bootstrap iterations was conducted within the MCI group (n = 11) to explore possible associations between CLD in the Flanker 1 mm condition at 50 mm distance (right-hand block) and neuropsychological scores. As expected, due to the small sample size, no statistically significant correlations emerged. However, some coefficients bordered statistical significance and may hold clinical interest. Specifically, CLD showed strong associations with MMSE (ρ = -0.63, p = 0.13) and Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT)–Immediate condition (ρ = -0.72, p = 0.07).

Collisions

All participants closely adhered to the experimental setup, avoiding any collisions, meaning they refrained from making contact with the flanker. In the control groups, there were two collisions recorded in HYA using the left, non-dominant hand; HOA engaged the flanker 8 times, all but one instance with the non-dominant hand in the Flanker 1 mm condition. In the patient group, three participants crossed over the distractor in the Flanker 1 mm condition, leading to a total of one collision (29th movement), two collisions (21st and 25th movements), and three collisions (8th movement and 21st movement, with the latter twice). No hypothesis testing analyses (e.g., Spearman correlation, Mann–Whitney U test, Crawford-Howell t-test) highlighted significant associations among collisions, kinematic outcomes, and neuropsychological performance.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether the analysis of visuomotor function under conditions of visual interference might improve the diagnosis of MCI. To achieve this, we examined patients with amnestic MCI due to AD during visually guided reaching movements. Right-handed patients with MCI, as well as healthy older adults and healthy young adults, were asked to reach a target dot located along their midsagittal/reaching axis. Movements were performed either with or without a small black square (the “flanker”), acting a distractor. This flanker could be positioned to the left or right of the reaching axis at its midpoint. When the flanker was on the left, participants used their right hand; when it was on the right, they used their left hand. We varied the flanker’s distance from the reaching axis to manipulate the magnitude of the interference effect. Participants were instructed to avoid passing over the flanker during movement execution.

Movement trajectories deviated away from the flanker when participants used their right hand. However, during the initial phases of the movements, the trajectories overlapped in both the presence and absence of the distractor. Effects only emerged as the flanker was approached. This confirms that our paradigm effectively minimized the influence of the flanker on hand movement kinematics during the early stages. As a result, the flanker acts as a distractor only when the hand nears it (and the target), making the onset of visual distraction inherently abrupt.

The amplitude of lateral deviations was a function of the left flanker proximity, namely, the closer the flanker was to the reaching axis, the greater the rightward deviations. This observation aligns with previous studies showing that movement trajectories deviate from a visual distractor when reaching for a target32,50. Notably, when the flanker was 1 mm from the reaching axis, patient trajectories deviated significantly to the right compared to those of control participants. This finding underscores how sub-clinical visuomotor deficits can be detected in MCI under highly cognitively demanding conditions17,51. Due to the extreme proximity of the flanker to the reaching axis, these trials were likely the most demanding in terms of perceptual and cognitive load. Under such conditions, executing eye-hand movements may necessitate rapid visual-perceptual processing, efficient attentional control, and inhibitory functions52. All participants exhibited increasing movement variability as they approached the reaching axis midpoint, irrespective of handedness and experimental condition. However, patients’ trajectories became increasingly inconsistent compared to healthy individuals25,53. Intriguingly, the lateral deviations observed when the flanker was 1 mm apart might effectively discriminate between patients with MCI and healthy older adults, supporting the potential diagnostic value of our paradigm. Our findings should be framed within an integrated context of neuropsychology, neurophysiology, and behavioral neuroscience for translational purposes.

A higher susceptibility to distractor interference may stem from a diminished ability to manage irrelevant information28. By assuming that both the flanker and the target evoke reaching movements in parallel, the attentional filtering mechanisms might resolve the competition between these positions by inhibiting movement towards the flanker, thereby leading trajectories to deviate from the latter32,50. From an anatomical-functional point of view, this “flanker effect” might be magnified in patients with MCI as a result of alterations within brain regions involved in screening out irrelevant or distracting objects, such as the pulvinar, the frontal cortex and—most importantly—the posteromedial parietal cortex21,24,53. Within the frontoparietal network, oculomotor areas in the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) are critically involved in goal-directed visual attention. Notably, as recently proposed, feedforward projections from the PPC to frontal areas regulate attentional processing during stimulus-driven attention tasks54. Still, the PPC, along the occipitoparietal/dorsal pathway, is crucial for assessing the significance of sensory inputs and processing target features necessary for planning reaching movements. When, as in our case, distraction occurs suddenly during the action, the resulting increased competition between target and distractor places critical demands on movement kinematics55,56. Notwithstanding, patients with MCI showed, on average, lower movement consistency compared to control participants. This finding may suggest that what appears to be a difficulty in resisting interference might actually indicate a preserved awareness of mild visuomotor deficits, potentially due to partially spared error monitoring processes57.

In the 5 mm condition, where the flanker was fairly distant from the reaching axis, patients showed slight rightward deviations during the initial movement phases but adjusted their trajectories as they approached the flanker. On the one hand, this finding may suggest that the distractor was less competitive, allowing for a “clearance space” to correct movement trajectory and maintain accuracy. On the other hand, patients may have exploited a predictive model grounded in a dynamic systems framework, leveraging a stochastic forward reachable set. In other words, they may have constructed a spatiotemporal representation to calculate the risk of collision by summing probabilities of spatial overlap between the hand and flanker58,59. In this vein, closer flankers, particularly the one positioned 1 mm away, were likely perceived as physical obstacles, prompting patients to widen their trajectories to avoid collision. This raises an interesting question about the neurocognitive mechanisms involved in obstacle recognition and collision avoidance.

When two objects collide, their interaction is governed by physical properties such as mass, velocity, and the forces at play. Humans may access these object-related properties by using “technical reasoning”, which is a form of nonverbal understanding of the physical world60,61. Technical reasoning is supported by the left inferior parietal lobe (IPL)62. Therefore, the ability to avoid a flanker might be attributed to the preservation of IPL. However, impaired superior parietal lobes (SPL), crucial for motor planning and eye-hand coordination15,63, may hinder adequate online motor control, resulting in less consistent trajectories. Thus, patients with MCI due to AD may show preserved technical reasoning abilities (IPL), while demonstrating suboptimal performance in planning eye-hand movements (SPL). These hypotheses require explicit testing in future studies.

Another plausible explanation for the poor visuomotor performance in patients with MCI is the corruption of their internal models. These experience-based, feedforward sensorimotor representations govern approximately 90% of movement planning by predicting the movement outcomes before they occur26. While our patients may have shown the ability to predict collisions through technical reasoning, practice with the task should have normalized their trajectories if their feedforward mechanisms were working properly. As previously proposed, impaired feedforward control in patients with MCI may be offset by the compulsory implementation of visual and proprioceptive feedback to control their actions. Yet, somatosensory inputs contribute to fine-tuning movement trajectory and speed when the hand is near the target, integrating information to and from internal models. Thus, sensory feedback alone is insufficient to guide reaching movements effectively26,64. It is important to note that, in this study, participants could see their hands, the distractor, and the target stimulus. However, participants used a non-inking stylus, lacking real-time visual feedback on their trajectory. This may have amplified the flanker effect, weakening the contribution of visuoperceptual compensatory mechanisms64. Also, reliance on environmental cues may worsen visuomotor function in older adults, particularly in those suffering from MCI, as recently suggested65,66.

When using their right hand, young adults reached the target dot with consistent average speed across all trials. Conversely, both healthy older adults and patients with MCI were slower in the presence of flankers compared to control trials. These findings support the idea that task complexity contributes to movement slowness in older adults67. Elderly people often engage in a “speed-accuracy trade-off,” sacrificing speed to make in-flight feedback-based corrections improving movement accuracy26,40.

We observed perturbations in movement kinematics when flankers were placed to the left of the participants28. According to the right hemi-aging model, the right hemisphere exhibits greater age-related decline than the left one68. Consequently, the right hemisphere’s processing of stimuli in the left hemifield might be disrupted to some extent in patients with MCI. Supporting this, there is evidence of severe cortical atrophy in the right temporal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices in patients with amnestic MCI69. These regions are functionally connected to the lateral parietal cortex within the executive-control network70 and supplementary motor areas involved in inhibitory control71. Additionally, a marked glucose hypometabolism in the right hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere has been found in patients with MCI due to AD72. However, gray matter frontal atrophy seems to be more pronounced in the left hemisphere compared to the right hemisphere in patients with amnestic MCI73. Signs of tautopathy have been identified more prominently in the left hemisphere, especially in the frontal cortex, temporal cortex, thalamus, and dorsal striatum20. Since the activity of each hand is primarily regulated by the contralateral hemisphere, our findings may suggest reduced motor control of the right upper limb by the left hemisphere. Notably, some studies have reported reduced dominant hand dexterity in patients with MCI74. Hand dominance may decrease as the neurodegenerative disease progresses, resulting in a gradual reduction in manual asymmetry75. Therefore, the right vs. left dissociation observed might result from a loss of hand dominance, increased non-dominant hand superiority, or both74.

The present study lacks the statistical power to draw exhaustive diagnostic conclusions, rendering it exploratory in nature from this perspective. However, our results appear promising, supporting the idea that a simple visuomotor task might differentiate between healthy aging and MCI, with performance on par with widely used cognitive assessments such as the MMSE. Specifically, our preliminary findings suggest that if an elderly individual deviates from the reaching axis by 1.79 mm or more at a distance of 50 mm in the trials within the Flanker 1 mm condition, there is an 87% probability that they have indeed amnestic MCI due to AD. Also, our task seems to be sensitive to disease severity (i.e., MMSE) and memory troubles (i.e., RAVLT), supporting its criterion validity76,77. Future studies with a larger sample size are needed to enhance the validity of these findings.

From a diagnostic perspective, the visuomotor function has largely been unexplored in clinical settings, and there is currently no consensus on the best protocol for MCI evaluation. Emphasis should be placed on flexible, time-efficient, and cost-effective tools, which can be integrated into composite neuropsychological batteries for outpatient and secondary care settings40. Our paradigm, if converted into a digital tool, may have potential for clinical applications. In this respect, one might consider developing a digital equivalent of the paradigm described here, with the goal of modernizing and automating a task that is deeply rooted in the “classic” experimental neuropsychology framework. In its digital version, the stimuli may be displayed on a screen, using the mouse cursor in place of the electronic stylus. This setting may increase visuospatial recalibration demands due to the dissociation between action and visual planes, which significantly impacts visuomotor function17. Still, porting the task to tablet or smartphone platforms may be advisable to facilitate more seamless integration into clinical settings, offering a practical alternative to computer-based setups. Rigorous normative and clinimetric studies are needed to validate our task for diagnostic aims.

Future studies may leverage Virtual Reality (VR) environments to gain deeper insights into visuomotor function across different task conditions. VR guarantees precise control over the visibility and salience of relevant stimuli, such as the participant’s hand and target. Consequently, VR-based paradigms may support a systematic analysis of how varying levels of visual information and environmental complexity impact hand movements. This method may help clarify how patients with MCI adapt their internal models under different visibility conditions and why their movements dramatically deviate from distractor position78,79. Notably, the implementation of eye-tracking (ET) tasks in real-world or virtual environments may improve the understanding of eye-hand behavior in patients with MCI. Tracking the number and duration of gaze fixations and the frequency of gaze shifts between target and distractor, may provide additional clues into how visual attention functions in patients with MCI. It may also shed light on how feedforward mechanisms and technical reasoning enable collision prediction and performance monitoring during simple visually guided reaching tasks60,80,81.

Therapeutically, non-pharmacological interventions that focus on upper-extremity motor exercises may improve both cognitive and functional outcomes82. As patients with MCI may predominantly rely on feedback-based control mechanisms during aimed hand movements24, addressing any visual impairments or incorporating visual aids could be beneficial in training programs. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving visuomotor function across various endpoints, ideally in ecological settings.

Conclusions

This study introduces a novel paradigm for identifying patients with MCI due to AD by analyzing visuomotor function under conditions of visual interference. We found that simple goal-directed reaching movements can be deflected by visual distractors. Specifically, trajectory deviations—particularly under highly distracting conditions—emerged as a potential biomarker to distinguish patients with MCI from healthy controls. Notably, our visuomotor task demonstrated diagnostic accuracy potentially comparable to established tools like the MMSE. This suggests that visuomotor assessments could be seamlessly integrated into clinical practice, offering an efficient and scalable method for screening and monitoring cognitive decline. The development of digitized visuomotor tools, feasibly implemented in virtual reality and integrated with oculometric measures, could revolutionize the evaluation of MCI-related sensorimotor dysfunctions in outpatient and secondary care settings, promoting earlier and more accurate diagnosis.

The visuomotor deficits in patients with MCI might stem from impairments in attentional filtering and feedforward mechanisms, which are associated to changes in critical brain areas such as the parietal cortex. This brain region is central to a framework of multimodal information integration—primarily visuospatial and sensorimotor—that is often disrupted in AD, expanding the current neurocognitive understanding of the disease beyond the traditional focus on the medial temporal lobe. Although medial temporal atrophy is classically considered the hallmark of AD pathology, its pathognomonic value has been re-evaluated. Indeed, it has been observed in various other conditions, including diabetes, bipolar disorder, frontotemporal dementia, and Lewy-related pathology83. In contrast, parietal cortex dysfunctions appear to play a more pivotal role in the progression of AD77,84. Furthermore, disruptions in dorsal projections converging into medial temporal regions for visuospatial processing and motor learning may account for many early symptoms of AD, such as memory loss, difficulty completing familiar tasks, topographic disorientation, and challenges in coordinating visual and spatial information.

In conclusion, this study bridges the gap between cognitive and motor abilities, emphasizing the importance of a holistic approach to evaluating patients’ functioning. By highlighting the diagnostic potential of visuomotor measures, we advocate for their integration as a main character in evaluating cognitive decline. This work lays the groundwork for a paradigm shift in clinical practice, with the potential to enhance management strategies for patients with MCI due to AD.

Materials and methods

Participants

Consecutive patients with suspected MCI were recruited from the Neurology Outpatient Clinic of the Centro Traumatologico Ortopedico (CTO) Hospital (Neurological Unit, Azienda Ospedaliera di Rilievo Nazionale “Ospedali dei Colli”, Naples, Italy) for diagnostic or treatment purposes. All patients underwent a neurological examination and an extensive formal neuropsychological assessment (see Supplementary Table S1 online). Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 60 years, ≥ 5 years of education, and a clinical diagnosis of amnestic MCI based on Petersen’s algorithm1. A concurrent etiological diagnosis of amnestic MCI due to AD, based on National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA-2011) criteria, was also required9. Healthy older (HOA) and young adults (HYA) participated in the study as controls. Inclusion criteria for both HOA and HYA were having at least 5 years of formal education, adjusted scores at MMSE and Frontal Assessment Battery-15 (FAB15) above the normative cutoff85,86,87, absence of cognitive complaints, and no current treatments with psychotropic drugs that could interfere with cognition. Individuals aged 60 years or older were enrolled in the HOA group, while those aged between 18 and 39 years were enrolled in the HYA group. Patients and controls reported no prior or current history of head trauma, psychiatric disorders (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, apathy), major health conditions, or substance abuse (e.g., alcohol, drugs). Participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, were right-handed, and did not wear mobility devices such as prostheses or braces. All participants were pseudonymized and informed that their data would be used solely for research purposes, ensuring anonymity and compliance with current laws on privacy. The present study was carried out in agreement with the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Scientific Institute for Research, Hospitalization, and Healthcare (IRCCS) Pascale (protocol no. 1/20). Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Apparatus and stimuli

Participants sat in a comfortable chair positioned in front of a table where a digitizing tablet (56.5 cm in width and 42.5 cm in depth) was located. The tablet featured an active surface of 45.5 cm × 30.5 cm, enabling the recording of movements using a non-inking electronic stylus. The stimuli were two vertically aligned dots, each 2 mm in diameter, printed on A4 white paper. The proximal white dot was the starting position, while the distal black dot was the target position. The distance between the two dots’ centers (i.e., the reaching axis) was 200 mm. A 15 mm2 black square (the “flanker”) could flank the reaching axis. In turn, the flanker could be arranged either on the left or on the right of the reaching axis, at a distance of 1 mm, 3 mm, or 5 mm apart from the axis connecting the lateral edge of the dots, with the flanker side midpoint matching the midpoint of the reaching axis. Using the edge of the dot, instead of its center, as a reference for placing the flankers aimed to prevent the closest flanker, positioned 1 mm apart, from being a physical (geometrical) obstacle to movement. Stimuli were constructed by means of Canvas™ X GIS 2019 software. Examples of the stimuli are depicted in Fig. 4.

Examples of stimuli used in the experiment. The left panel shows the control condition with no flanker. The middle panel presents the stimuli with a flanker to the left of the reaching axis, used in “right hand” trials. The right panel displays the stimuli with a flanker on the right of the reaching axis, used in “left hand” trials. The proportions among elements are not to scale, as the figure is for illustrative purposes only.

Experimental procedure

The examiner placed the stimuli one by one on the active surface of the tablet, covered by a transparent cellulose acetate sheet. The transparent sheet was used to minimize friction and thereby enhance movement smoothness. Each stimulus was arranged so that (a) the reaching axis aligned with the participants’ midsagittal axis, and (b) the proximal dot was about 20 cm away from the participants’ trunk. At the beginning of each trial, participants held the non-inking electronic stylus and then positioned its tip within the starting dot. Then, they were required to execute a reaching movement from the starting to the target dot at a natural speed, without stopping the movement. Once the movement ended, participants were instructed to replace the stylus tip within the starting dot and then repeat the movement. When the stimuli were flanked by a distractor, the examiner asked participants to perform the reaching movements without passing over the flanker: “Please, don’t touch the flanker!”. If the participant’s movement trajectory made contact with the flanker, the examiner let the movement finish before informing the participant of the “collision”. The examiner then invited them to repeat the movement, reinforcing the original instructions.

Each participant performed 80 trials divided into 2 blocks, one performed with the right hand and the other with the left hand. Within each block, the first 10 trials employed stimuli without the flanker (control condition). Subsequently, 30 flanked stimuli, 10 for each of the three distances (flanker 1 mm, 3 mm, and 5 mm apart) were presented. In the “right hand” block, the flankers were arranged on the left of the reaching axis, whereas in the “left hand” block they were displaced on the right of the reaching axis. This procedure prevented the hand from masking the flanker while performing the reaching movement. The order of blocks was randomized within subjects. For each block, the presentation order of the flanked stimuli was randomized and counterbalanced within subjects.

The position of the electronic stylus tip was recorded over time (every 20 ms) in x- and y-coordinates with an accuracy of 0.25 mm, using a custom software written in G-Language and executed in LabView (National Instruments, Austin, Tx, USA). In line with previous research28,88, the mean constant lateral deviation (CLD) of the trajectories at 20 mm, 50 mm, and 90 mm from the starting dot was estimated in each trial. The low vertex of the flanker was 90 mm away from the starting dot. The standard deviation of the trajectories, i.e., the variable lateral deviation (VLD), was also extracted and served as a measure of movement consistency. Finally, the mean velocity (cm/sec) of the entire movement, i.e., until reaching the target dot, was calculated.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequency for categorical variables and mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables. All quantitative variables showed skewness and kurtosis values within the range of -2 and + 2, indicating no significant deviations from parametric probability distributions89. For demographic and clinical characteristics, between-group comparisons were performed by two-way chi-squared test (χ2) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), as appropriate. Kinematic data were analyzed using mixed-design ANOVAs. Specifically, as for kinematic data of CLD and VLD, a three (group: HYA × HOA × MCI) by four (condition: control × flanker 1 mm × flanker 3 mm × flanker 5 mm) by three (distance: 20 mm × 50 mm × 90 mm) mixed factorial ANOVA was conducted for each block, i.e., right-handed and left-handed movements. Similarly, a 3 × 4 mixed ANOVA was performed to analyze data on movement velocity, with group as the between-subject factor and condition as the within-subject factor. If the assumption of sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied to degrees of freedom. Lastly, a receiving operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was run to test the diagnostic/clinimetric value of the most discriminatory parameter, if any90. Spearman’s rank correlation (ρ) with 1,000 bootstrap iterations was conducted within the MCI group to examine potential associations between key kinematic measures and neuropsychological test scores. The nominal alpha (α) level was set to 0.05. For any post-hoc analysis, p-values were adjusted using Bonferroni’s method (pbonf). Effect sizes were expressed as eta squared (η2), partial eta squared (\({\eta }_{p}^{2}\)), or Cohen’s d, and interpreted according to recognized rules of thumb: small (η < 0.06, d = 0.20–0.50), medium (η = 0.06–0.13, d = 0.51–0.80), and large (η ≥ 0.14, d > 0.80)91. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 and R 4.3.2.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Petersen, R. C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 256, 183–194 (2004).

Petersen, R. C. et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 90, 126–135 (2018).

Canevelli, M. et al. Spontaneous reversion of mild cognitive impairment to normal cognition: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 17, 943–948 (2016).

Oltra-Cucarella, J. et al. Risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease for different neuropsychological Mild Cognitive Impairment subtypes: A hierarchical meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Aging 33, 1007–1021 (2018).

Petersen, R. C. et al. Current Concepts in Mild Cognitive Impairment. Arch. Neurol. 58, 1985–1992 (2001).

Ilardi, C. R. Anosognosia for Memory Deficits in Mild Cognitive Impairment: “My Memory Runs as Usual”. in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability (eds. Bennett, G. & Goodall, E.) 1–13 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40858-8_109-1.

Rosenberg, P. B. et al. The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms in MCI with incident dementia and Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 21, 685–695 (2013).

Gómez-Ramírez, J., Ávila-Villanueva, M. & Fernández-Blázquez, M. Á. Selecting the most important self-assessed features for predicting conversion to mild cognitive impairment with random forest and permutation-based methods. Sci. Rep. 10, 20630 (2020).

Albert, M. S. et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 270–279 (2011).

Koppelmans, V., Silvester, B. & Duff, K. Neural Mechanisms of Motor Dysfunction in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 6, 307–344 (2022).

Eggermont, L. H. et al. Lower-extremity function in cognitively healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 91, 584–588 (2010).

Seidler, R. D. et al. Motor control and aging: links to age-related brain structural, functional, and biochemical effects. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 34, 721–733 (2010).

Larivière, S. et al. Functional and effective reorganization of the aging brain during unimanual and bimanual hand movements. Hum. Brain Mapp. 40, 3027–3040 (2019).

Ilardi, C. R., Iavarone, A., La Marra, M., Iachini, T. & Chieffi, S. Hand movements in Mild Cognitive Impairment: clinical implications and insights for future research. J. Integr. Neurosci. 21, 67 (2022).

Karnath, H.-O. & Perenin, M.-T. Cortical control of visually guided reaching: evidence from patients with optic ataxia. Cereb. Cortex N. Y. N 1991(15), 1561–1569 (2005).

Bai, F. et al. Abnormal integrity of association fiber tracts in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. J. Neurol. Sci. 278, 102–106 (2009).

Hawkins, K. M. & Sergio, L. E. Visuomotor impairments in older adults at increased Alzheimer’s disease risk. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 42, 607–621 (2014).

Kim, H., Kim, J. S. & Chung, C. K. Identification of cerebral cortices processing acceleration, velocity, and position during directional reaching movement with deep neural network and explainable AI. NeuroImage 266, 119783 (2023).

Onen, F. et al. Leukoaraiosis and mobility decline: a high resolution magnetic resonance imaging study in older people with mild cognitive impairment. Neurosci. Lett. 355, 185–188 (2004).

Dani, M. et al. Tau aggregation correlates with amyloid deposition in both mild cognitive impairment and alzheimer’s disease subjects. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 70, 455–465 (2019).

Bernstein, A. S., Rapcsak, S. Z., Hornberger, M. & Saranathan, M. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. structural changes in thalamic nuclei across prodromal and clinical Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD. 82, 361–371 (2021).

Benarroch, E. E. Pulvinar: associative role in cortical function and clinical correlations. Neurology 84, 738–747 (2015).

Camarda, R. et al. Movements execution in amnestic mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Neurol. 18, 135–142 (2007).

Mitchell, A. G. et al. Peripheral reaching in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cortex 149, 29–43 (2022).

Yan, J. H., Rountree, S., Massman, P., Doody, R. S. & Li, H. Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment deteriorate fine movement control. J. Psychiatr. Res. 42, 1203–1212 (2008).

Elliott, D. et al. The multiple process model of goal-directed reaching revisited. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 72, 95–110 (2017).

Milner, A. D. & Goodale, M. A. Two visual systems re-viewed. Neuropsychologia 46, 774–785 (2008).

Chieffi, S. et al. Age-related differences in distractor interference on line bisection. Exp. Brain Res. 232, 3659–3664 (2014).

Simone, P. M. & Baylis, G. C. Selective attention in a reaching task: effect of normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 23, 595–608 (1997).

Desimone, R. & Duncan, J. Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 193–222 (1995).

Reichenbach, A., Franklin, D. W., Zatka-Haas, P. & Diedrichsen, J. A dedicated binding mechanism for the visual control of movement. Curr. Biol. CB 24, 780–785 (2014).

Tipper, S. P., Howard, L. A. & Jackson, S. R. Selective Reaching to Grasp: Evidence for Distractor Interference Effects. Vis. Cogn. 4, 1–38 (1997).

Cisek, P. & Kalaska, J. F. Neural mechanisms for interacting with a world full of action choices. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 33, 269–298 (2010).

Castiello, U. Grasping a fruit: selection for action. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 22, 582–603 (1996).

effects on distraction. Brand-D’Abrescia, M. & Lavie, N. Task coordination between and within sensory modalities. Percept. Psychophys. 70, 508–515 (2008).

Chapman, C. S. & Goodale, M. A. Obstacle avoidance during online corrections. J. Vis. 10, 17 (2010).

Houghton, G. & Tipper, S. P. A model of inhibitory mechanisms in selective attention Inhibitory Processes of Attention, Memory and Language (Academic Press, 1984).

Shadmehr, R. & Wise, S. P. The Computational Neurobiology of Reaching and Pointing: A Foundation for Motor Learning (MIT press, 2004).

Salek, Y., Anderson, N. D. & Sergio, L. Mild cognitive impairment is associated with impaired visual-motor planning when visual stimuli and actions are incongruent. Eur. Neurol. 66, 283–293 (2011).

Ilardi, C. R. et al. The “Little Circles Test” (LCT): a dusted-off tool for assessing fine visuomotor function. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 35, 2807–2820 (2023).

Wobbrock, J. O., Findlater, L., Gergle, D. & Higgins, J. J. The aligned rank transform for nonparametric factorial analyses using only anova procedures. in Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 143–146 (ACM, Vancouver BC Canada, 2011). https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1978963.

Cnaan, A., Laird, N. M. & Slasor, P. Using the general linear mixed model to analyse unbalanced repeated measures and longitudinal data. Stat. Med. 16, 2349–2380 (1997).

Elkin, L. A., Kay, M., Higgins, J. J. & Wobbrock, J. O. An Aligned Rank Transform Procedure for Multifactor Contrast Tests. in The 34th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology 754–768 (ACM, Virtual Event USA, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3472749.3474784.

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E. & McHugh, P. R. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 12, 189–198 (1975).

Mandrekar, J. N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 5, 1315–1316 (2010).

Youden, W. J. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 3, 32–35 (1950).

Ilardi, C. R. et al. On the clinimetrics of the montreal cognitive assessment: cutoff analysis in patients with mild cognitive impairment due to alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. JAD 101, 293–308 (2024).

DeLong, E. R., DeLong, D. M. & Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988).

Obuchowski, N. A. ROC analysis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 184, 364–372 (2005).

Howard, L. A. & Tipper, S. P. Hand deviations away from visual cues: Indirect evidence for inhibition. Exp. Brain Res. 113, 144–152 (1997).

Schröter, A. et al. Kinematic analysis of handwriting movements in patients with Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, depression and healthy subjects. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 15, 132–142 (2003).

Lezak, M. D. Neuropsychological Assessment (Oxford University Press, 2004).

Yu, N.-Y. & Chang, S.-H. Characterization of the fine motor problems in patients with cognitive dysfunction - A computerized handwriting analysis. Hum. Mov. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2018.06.006 (2019).

Murray, J. D., Jaramillo, J. & Wang, X.-J. Working memory and decision-making in a frontoparietal circuit model. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 37, 12167–12186 (2017).

Castiello, U., Badcock, D. R. & Bennett, K. M. B. Sudden and gradual presentation of distractor objects: differential interference effects. Exp. Brain Res. 128, 550–556 (1999).

Leech, R. & Sharp, D. J. The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain J. Neurol. 137, 12–32 (2014).

Bettcher, B. M., Giovannetti, T., Macmullen, L. & Libon, D. J. Error detection and correction patterns in dementia: A breakdown of error monitoring processes and their neuropsychological correlates. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 14, 199–208 (2008).

Ammoun, S. & Nashashibi, F. Real time trajectory prediction for collision risk estimation between vehicles. in 2009 IEEE 5Th international conference on intelligent computer communication and processing 417–422 (IEEE, 2009).

Wang, X., Li, Z., Alonso-Mora, J. & Wang, M. Prediction-based reachability analysis for collision risk assessment on highways. in 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV) 504–510 (IEEE, 2022).

Federico, G., Osiurak, F. & Brandimonte, M. A. Hazardous tools: the emergence of reasoning in human tool use. Psychol. Res. 85, 3108–3118 (2021).

Lesourd, M. et al. Mechanical problem-solving strategies in Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia. Neuropsychology 30, 612 (2016).

Federico, G. et al. The cortical thickness of the area PF of the left inferior parietal cortex mediates technical-reasoning skills. Sci. Rep. 12, 11840 (2022).

Ilardi, C. R., Chieffi, S., Iachini, T. & Iavarone, A. Neuropsychology of posteromedial parietal cortex and conversion factors from Mild Cognitive Impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: systematic search and state-of-the-art review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 34, 289–307 (2022).

Ghilardi, M.-F. et al. Visual feedback has differential effects on reaching movements in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 876, 112–123 (2000).

Raab, M., de Oliveira, R. F., Schorer, J. & Hegele, M. Adaptation of motor control strategies to environmental cues in a pursuit-tracking task. Exp. Brain Res. 228, 155–160 (2013).

Kim, H. et al. Aging-induced degradation in tracking performance in three-dimensional movement. SICE J. Control Meas. Syst. Integr. (2024).

Ketcham, C. J., Seidler, R. D., Van Gemmert, A. W. & Stelmach, G. E. Age-related kinematic differences as influenced by task difficulty, target size, and movement amplitude. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 57, P54–P64 (2002).

Dolcos, F., Rice, H. J. & Cabeza, R. Hemispheric asymmetry and aging: right hemisphere decline or asymmetry reduction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 26, 819–825 (2002).

Apostolova, L. G. et al. Three-dimensional gray matter atrophy mapping in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 64, 1489–1495 (2007).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27, 2349–2356 (2007).

Nachev, P., Kennard, C. & Husain, M. Functional role of the supplementary and pre-supplementary motor areas. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 856–869 (2008).

Weise, C. M. et al. Left lateralized cerebral glucose metabolism declines in amyloid-β positive persons with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage Clin. 20, 286–296 (2018).

Liu, H. et al. Changes in brain lateralization in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A resting-state functional magnetic resonance study from Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Front. Neurol. 9, 3 (2018).

Vasylenko, O., Gorecka, M. M., Waterloo, K. & Rodríguez-Aranda, C. Reduction in manual asymmetry and decline in fine manual dexterity in right-handed older adults with mild cognitive impairment. Laterality 27, 581–604 (2022).

Ryan, J. J., Kreiner, D. S. & Paolo, A. M. Handedness of healthy elderly and patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neurosci. 130, 875–883 (2020).

Di Cecca, A. et al. Distortion errors characterise visuo-constructive performance in Huntington’s disease. Clin. Neuropsychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2024.2411740 (2024).

Andrade, K. & Pacella, V. The unique role of anosognosia in the clinical progression of Alzheimer’s disease: a disorder-network perspective. Commun. Biol. 7, 1384 (2024).

Kim, H., Koike, Y., Choi, W. & Lee, J. The effect of different depth planes during a manual tracking task in three-dimensional virtual reality space. Sci. Rep. 13, 21499 (2023).

Choi, W., Lee, J., Yanagihara, N., Li, L. & Kim, J. Development of a quantitative evaluation system for visuo-motor control in three-dimensional virtual reality space. Sci. Rep. 8, 13439 (2018).

Tamaru, Y., Matsushita, F. & Matsugi, A. Tests of abnormal gaze behavior increase the accuracy of mild cognitive impairment assessments. Sci. Rep. 14, 19512 (2024).

Federico, G. & Brandimonte, M. A. Looking to recognise: the pre-eminence of semantic over sensorimotor processing in human tool use. Sci. Rep. 10, 6157 (2020).

Hesseberg, K., Tangen, G. G., Pripp, A. H. & Bergland, A. Associations between cognition and hand function in older people diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. Extra 10, 195–204 (2020).

Dubois, B. et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 13, 614–629 (2014).

Ma, H. R. et al. Cerebral glucose metabolic prediction from amnestic mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia: a meta-analysis. Transl. Neurodegener. 7, 9 (2018).

Carpinelli Mazzi, M. et al. Mini-mental state examination: new normative values on subjects in Southern Italy. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 32, 699–702 (2020).

Ilardi, C. R. et al. The frontal assessment battery 20 years later: normative data for a shortened version (FAB15). Neurol. Sci. 43, 1709–1719 (2022).

Measso, G. et al. The mini-mental state examination: Normative study of an Italian random sample. Dev. Neuropsychol. 9, 77–85 (1993).

Chieffi, S., Ricci, M. & Carlomagno, S. Influence of visual distractors on movement trajectory. Cortex. J. Devoted Study Nerv. Syst. Behav. 37, 389–405 (2001).

George, D. & Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update. (Allyn & Bacon, 2010).

Ilardi, C. R., Menichelli, A., Michelutti, M., Cattaruzza, T. & Manganotti, P. Optimal MoCA cutoffs for detecting biologically-defined patients with MCI and early dementia. Neurol. Sci. 44, 159–170 (2023).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. (Routledge, 2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health by “Progetti di Ricerca Corrente” and supported by grant from University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” (Protocol code n. 76400; date: June 5, 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R.I. and S.C.: conceptualization, methodology. C.R.I. and M.L.M.: formal analysis, investigation. C.R.I. and R.A.: investigation, data curation. A.I. and S.C.: resources. C.R.I. and G.F.: writing-original draft, visualization. A.S., G.S., and S.C.: supervision. A.S. and G.S.: project administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests .

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ilardi, C.R., Federico, G., La Marra, M. et al. Deficits in reaching movements under visual interference as a novel diagnostic marker for mild cognitive impairment. Sci Rep 15, 1901 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85785-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85785-7