Abstract

This paper introduces an analytical method for studying power transmission through an infinite array of helical-shaped metal particles in a lossy dielectric medium. While the assessment of composite slabs’ transmitted power has been extensively researched in the electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding field, many studies lack an adequate problem description. The primary inadequacy of these studies is the need for an analytical framework. This study, besides presenting a new approach to designing a concrete composite that leverages the magnetoelectric properties of the particles, making it suitable for EMI shielding, also employs a theoretical method to analyze the composite. A circuit model of the array is introduced using a modal field decomposition, which justifies the impact of helix transmission modes and the transverse magnetic field component on the shielding properties of the array. It is also shown that the resonances of the array can be tuned by engineering the helix properties. Furthermore, to broaden the applicable bandwidth of the composite, a multi-layer structure is proposed. The computational load of the proposed method demonstrates exceptional speed due to its circuit model foundation. The model yields valuable results compared to experimental measurement, making it ideal for optimizing various shielding composite structures for EMI shielding applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding is the discipline of protecting electronic devices from electromagnetic power. There are various traditional methods for generating a shielded room, such as covering the walls with aluminum foil or using a metal chamber. In addition, the construction of globally shielded buildings is currently being developed for diverse purposes1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Some of the modern buildings use particle-loaded concrete instead of traditional concrete. This cement-based composite can reduce transmitted power significantly and shield against electromagnetic waves while improving the structure’s mechanical properties. Different macroscopic or microscopic particles can be added to the cement matrix to create a sturdy slab for EMI shielding10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,22. For instance, Carbon-based additives, such as graphene, have been widely used as fillers10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. While these additives are valuable, macroscopic additives are more useful for industrial-scale concrete composite designs and have demonstrated effectiveness in empirical tests. Incorporating macroscopic fibers into the structure not only enhances EMI shielding but also improves the mechanical properties of concrete composites, such as ductility. Additionally, it facilitates the integration of microscopic additives, which is particularly advantageous for producing ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC)23,24. For example, steel fibers have been used within cement matrices for EMI shielding22.

A significant limitation in previous studies within this field is the lack of an analytical model. Most research uses experimental methods and measurements, focusing significantly on a single or narrow frequency band. This study aims to design a structure for concrete composites and propose an analytical method for assessing the power transmitted through its slab. The proposed structure is a system of helical-shaped particles arranged in a regular array and embedded within a concrete slab. New methods have been recently developed for organizing the conductive particles in concrete paste, which makes the proposed structure feasible and applicable for industrial implementations24,25,26. Helical-shaped particles represent a well-known type of chiral inclusion that can be employed for electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding applications, particularly due to their resonant properties27,28,29. Moreover, they can be analytically assessed because of their geometry and wide previous studies on their electromagnetic characteristics and applications. Furthermore, this is the initial step towards an analytical method for analyzing and estimating the transmitted power of general structures, such as concrete composites, that contain randomly distributed helical particles as additives30.

Previous studies have analyzed similar topics, such as the analytical investigation of a system consisting of one, two, or more parallel infinite periodic arrays of identical and identically oriented scattering particles, and have derived the reflection and transmission coefficients31,32. Additionally, chiral scatterers’ electric and magnetic polarizabilities are estimated using an analytical antenna model27. Another study investigates the problem of electromagnetic mutual coupling among the particles in a three-dimensional array, including chiral particles33. In another previous study, a system consisting of two parallel infinite periodic arrays containing Ω-shaped particles has been investigated34. Another experimental study has already examined the omega media35. The reflection and transmission coefficients of an infinite periodic array of chiral particles have been estimated analytically and used to create various passive microwave devices36. Furthermore, the electromagnetic field scattered by a helix is studied, and it is used to estimate the constitutive parameters of a chiral composite made of randomly distributed helical particles in a host medium28. In addition, the constitutive parameters of a helix-loaded composite and the reflection and transmission coefficients of the slab are derived using a Maxwell-Garnett model29. In all of the aforementioned studies, the analysis and results are only valid within the frequency range where the unit cell or particle’s size is small compared to the wavelength, which is a significant restriction.

This paper analyzes a multi-layer array of helical particles to estimate and evaluate its transmitted power over a wide frequency range, focusing on the resonant situation. We first simplify the complicated structure into a sub-problem and analyze a single-layer dense periodic array to propose a simple and appropriate model. Then, a straightforward method has been extended for a multi-layer array analysis. The method proposed in this study utilizes modal field decomposition and a circuit model to analyze the complicated structure of the array. The different modes (paths) that effectively transfer the power from one side of the array to the other are modeled by their corresponding transmission lines. Each transmission line is modeled as a corresponding 2-port, and the problem is reduced as a circuit model. Since the proposed method is based on a circuit model, it is significantly fast and allows for a quick estimation of the response of the designed structure. Therefore, it is suitable for optimizing the concrete composites designed for EMI shielding applications. Traditional numerical techniques involve a significant computational burden, requiring powerful hardware and long computation times. To reduce computational complexity, we accept a small degree of inaccuracy.

Helical particles arranged in a planar array can mimic the characteristics of a cylindrical waveguide and its dominant mode’s surface current along the helical wire. This behavior results in evanescent wave propagation, effectively reducing the transmitted power within the array’s resonance frequency range below the cutoff frequency of the dominant mode. However, under specific conditions, the helix transmission modes can be excited and transmit power through the array, which can disrupt the shielding attribute. This study investigates these phenomena in more detail. The proposed structure effectively attenuates the transmitted electromagnetic power over a wide frequency range while leveraging minimal metal additives because of the use of helical particles as the below cutoff waveguides and evanescent wave propagation. This results in a lightweight concrete composite material while maintaining a substantial degree of shielding effectiveness in a wide frequency range, making the proposed structure suitable for EMI shielding applications37. In other words, utilizing helical particles arranged in a multi-layer array makes it possible to decrease the number of additives while improving the shielding effectiveness of concrete composites.

The paper is structured into three main Sects.: “Results,” “Discussion,” and “Methods.” The problem geometry and theoretical framework and formulations are presented in the section “Results,” which includes seven sub-sections. Firstly, “Geometry of the Problem” will explain the geometry of the multi-layer array and the helically shaped particles. The Sects. “Modal Field Decomposition for a Planar Array of Cylinders” and “Example: Transmitted Power Calculation for the Planar Array of Cylinders” will present the proposed method and an example for an infinite periodic planar array of cylinders, and subsequently, the Sects. “Modal Field Decomposition for a Planar Array of Helices” and “Example: Transmitted Power Calculation for the Planar Array of Helices” will cover the same for a planar array of helical particles. The results of the proposed method for a planar array will be compared with full-wave simulations and experimental measurements. After that, the problem formulation and proposed method for a multi-layer array of helices will be presented in “Transmitted power calculation for Multi-layer Array of Helices”. The results of the proposed method for a 6-layer array and a comparison with full-wave simulations and experimental measurements will be discussed in “Example: The Transmitted Power through a 6-layer Array of Helices.” The conclusion will be available in the Sect. “Discussion” and the methods and material for reproducing the results of the paper, such as the flowchart of MATLAB script, will be finally provided in Sect. “Methods.”

Results

Geometry of the problem

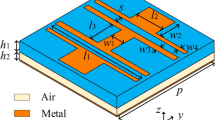

We aim to propose a structure for concrete composites consisting of a system of two, three, or more parallel infinite periodic planar arrays of helical particles For EMI shielding applications. In each planar array, the particles must be very close to each other to achieve considerable shielding effectiveness. For example, we have chosen six parallel infinite periodic planar arrays, as shown in Fig. 1a and b. All of the planar arrays are located in a host medium. In this example, the preferred host medium is concrete.

(a) Three neighboring unit cells of the 6-layer array. It shows all six parallel planar arrays. (The blue transparent cube represents the surrounding concrete material as the host medium). (b) The unit cell of the same array. (c) The unit cell of the infinite periodic planar array of metal helical particles. (d) Nine neighboring unit cells of the array shown in (c). (e) The unit cell of the infinite periodic planar array of metal cylinders (f) Nine neighboring unit cells of the array shown in (e).

The elements in each planar array have identical orientation and geometry, but each planar array can differ in element and unit cell size from the others. In our example, the parallel planar arrays with different unit cell sizes were selected to achieve a wide band structure. Therefore, each planar array’s particle and unit cell size is a scale of its previous planar array. Generally, the distances between the arrays are assumed to be arbitrary and depend on the utility and design. The helical particles can have several turns. For the 6-layer array in our study, we employed 1.75-turn helical particles with an additional ring (a helix with zero pitch angle) at one end within each unit cell (Fig. 1b). This design creates a bi-anisotropic medium capable of addressing both cross-polarizations of incident waves, which is essential for EMI shielding applications. In contrast, in our other example, the single-layer array (Fig. 1c and d) utilized helices with 1.5 turns. It is crucial to note that the pitch angle of these helical particles must remain below 8 degrees to ensure optimal performance.

We intend to propose an analytical method to assess the shielding property of this multi-layer array for a normally incident, linearly polarized electromagnetic wave. In our example, the incident wave propagates in the -z direction with the electric field in the +y direction.

Breaking down the main complex problem into simpler sub-problems, a 1-layer array, facilitates the solving process. Thus, to simplify the structure, we first analyze a single infinite periodic planar array of helical particles, shown in Fig. 1c and d. On the other hand, this single planar array of helices can be broken down again into a simpler sub-problem, an infinite periodic planar array of conductive (metal) cylinders, illustrated in Fig. 1e and f. The geometry of the helical particle with a small pitch angle is highly correlated with the geometry of a cylindrical waveguide with the same radius. Namely, a helical wire can imitate the dominant mode’s surface current of a cylindrical waveguide. Therefore, the boundary condition for the unit cell of both planar arrays of helices and a planar array of cylinders is almost similar. Fig. 2a-d displays the electric field configuration of both planar arrays on an identical cross-section. It can be observed that the field patterns of both arrays are equivalent, below and above the dominant mode’s cutoff frequency of the cylindrical waveguide. In general, these electric field configurations are similar to the electric field configuration of cylindrical waveguide’s TE11 mode. Figure 2e-l depict the contours of the z-component of the magnetic field (magnitude of Hz) in the planar array of cylinders and the planar array of helices at two selected frequencies, 2 and 3.5 GHz, on two orthogonal planes: y = 0 mm (xz-plane) and x = 0 mm (yz-plane). Among all components of the electric and magnetic fields, the z-component of the magnetic field (Hz) is the most important component of the TE modes of a waveguide that extends along the z-axis, as all other components can theoretically be derived from this fundamental component. These contours compare the magnetic field configurations of the two planar arrays. To better illustrate the magnetic field patterns and the attenuation of the field magnitude along the z-axis below the cutoff frequency, a seven-turn helix with a radius of 12 mm (matching the cylinder’s radius) was chosen for comparison. The TE11 mode cutoff frequency for this cylindrical waveguide is 3.1 GHz. Figure 2e-h show that the field configurations for the two arrays on the y = 0 plane are highly similar at both 2 GHz and 3.5 GHz. These patterns correspond to the Hz configuration of the TE11 mode, with Hz magnitude increasing near the conductors at φ=0° and φ=90° and significantly decreasing near x = 0 when the electric field is oriented in the y-direction. At 2 GHz, below the cutoff frequency, attenuation of Hz along the z-axis is evident in both arrays. This attenuation disappears at 3.5 GHz, a frequency above the TE11 cutoff. Similarly, Fig. 2i-l demonstrate nearly identical field configurations for both arrays on the x = 0 plane at 2 GHz and 3.5 GHz, reflecting the Hz pattern characteristic of the TE11 mode of a cylindrical waveguide. Finally, Fig. 2m and n illustrate the transmitted power through the cylinder and seven-turn helix arrays as a function of frequency. Both arrays show similar behavior: significant attenuation of transmitted power below the TE11 cutoff frequency (across their resonance frequency range, around 2 GHz) and efficient transmission without notable attenuation above the cutoff frequency of 3.1 GHz. Therefore, analyzing an infinite periodic planar array of cylinders is a sub-problem for analyzing a planar array of helices.

(a) The electric field configuration of an infinite periodic planar array of circular waveguides on a specific cross-section in the resonance frequency range below its TE11 mode cutoff frequency. (b) Similar to (a), beyond the TE11 cutoff frequency. (c) The electric field configuration of an infinite periodic planar array of seven-turn helices on a specific cross-section in the resonance frequency range, below the TE11 mode cutoff frequency of a circular waveguide with an identical radius. (d) Similar to (c), beyond the aforementioned TE11 cutoff frequency. (e–f) The contour of Hz magnitude in the array of cylinders at 2 GHz and 3.5 GHz on the y = 0 plane (xz-plane). (g-h) The contour of Hz magnitude in the array of helices at 2 GHz and 3.5 GHz on the y = 0 plane (xz-plane). (i-j) The contour of Hz magnitude in the array of cylinders at 2 GHz and 3.5 GHz on the x = 0 plane (yz-plane). (k-l) The contour of Hz magnitude in the array of helices at 2 GHz and 3.5 GHz on the x = 0 plane (yz-plane). (m) The transmitted power through the infinite periodic planar array of cylinders. (n) The transmitted power through the infinite periodic planar array of helices. (The blue transparent cube represents the surrounding concrete material as the host medium. The total time-averaged power density of the incident wave is assumed to be 1 W/m2 = 0 dBW/m2.)

Modal field decomposition for a planar array of cylinders

The geometry of the unit cell of an infinite periodic planar array of conductive cylinders is shown in Fig. 1e and f. The geometry can be divided into four well-known electromagnetic passive devices (paths), effectively transmitting electromagnetic power from one side of the array to another: (1) The cylindrical conductor’s inner surface, the cylinder’s enclosed space, operates as a standard cylindrical waveguide. Its TE11 mode’s electric field configuration is obvious in the black circle in Fig. 3a. We name it “conductive waveguide.” (2) The outer side of the cylindrical conductors, the space outside and among four adjacent cylinders, operates as another cylindrical waveguide with a radius equal to that of a circle with an area equivalent to the cross-section of the space between the cylindrical conductors of four adjacent unit cells. Its dominant mode’s electric field configuration is obvious in the red circle in Fig. 3a, at the center of the illustrations. We name it “hypothetical waveguide” because it is physically invisible. (3) The space outside and among four adjacent cylinders operates as a multi-conductor transmission line. Because of the geometric symmetry among four adjacent unit cells, the multi-conductor transmission line can be considered two pairs of parallel circular conductor transmission lines with identical characteristics. They can be observed in Fig. 3b. (4) The thickness (edge) of the cylinder operates as a scatterer, which scatters and reflects electromagnetic power off the edges of the cylinders. This can be modeled with a short circuit termination.

(a) The large black circle represents the conductive waveguide. The small red circle represents the hypothetical waveguide. (b) Two pairs of transmission lines are shown as diagonal circles, which represent the conductors of the parallel wire transmission line. (c) The magnitude of the electric field inside the conductive cylinder along its axis (the -z axis in blue) and outside the cylinder along a line at the corner of the unit cell and parallel to the axis (the -z′ axis in red).

Figure 3c demonstrates the Electric field magnitude versus the distance from the plane of the beginning of the cylinder, inside and outside the cylinder, which is derived by a full-wave simulation. The line graph (I) reveals that the field pattern at the center of the cylinder is similar to that of the standard cylindrical waveguide with the same size and dominant mode TE11 excitation. It decreases exponentially along the conductive cylinder at frequencies below the cylindrical waveguide TE11 cutoff frequency. It indicates the existence of the conductive waveguide. On the other hand, the pattern of line graph (II) can be estimated by the sum of two wave modes: an evanescent wave and a traveling wave with unequal electric field phases. These two modes, respectively, imply the existence of the hypothetical waveguide in the below cutoff condition and the parallel wire transmission line.

The TEM incident wave excites particular modes of the cylindrical conductive and hypothetical waveguides. For instance, the TM waveguide modes cannot be excited well by an incident TEM plane wave due to the field configuration of these modes on the cross-section of a circular waveguide. The incident E and H fields cannot effectively become tangential to the electric and magnetic field vectors of TM modes, and distinct infinitesimal elements cancel each other on the cross-section. According to this argument, the TE11 mode is the most effective waveguide mode as it is significantly excited by the incident wave and carries the supreme fraction of the total power. However, to minimize the deviation of the proposed method results in the high-frequency region of the specified frequency range, we have selected three effective high-order modes, TE21, TE31, and TE41, out of all available modes. These modes are selected based on the affinity between their field direction and the incident wave field direction.

The propagation constant and characteristic impedance of all selected modes are calculated easily because they are well-known modes. Then, each of the selected modes is represented by a 2-port, using either its scattering [S], transmission [T], or admittance matrix [Y]. Moreover, the proposed method also considers the effect of lossy materials on the results. We attempted to estimate the attenuation constant of the traveling wave in all transmission lines considered. Conduction (ohmic) and dielectric losses of transmission lines corresponding to the different waveguide modes can be calculated by standard perturbational methods.

Due to the similarity between the field configuration of the TE11 mode of the conductive waveguide and the hypothetical waveguide, the incident wave simultaneously excites both the conductive and hypothetical waveguide’s TE11 modes. Thus, the TE11 mode of the conductive waveguide is parallel to the TE11 mode of the hypothetical waveguide and, both together, are modeled as a single 2-port. This approach is also used for all other TEm1 modes. Fig. 4a displays the 2-port model for the TEm1 waveguide mode with m=1,2,3,4, shown by a red block.

(a) The desired 2-port for TEm1 waveguide mode, m = 1,2,3,4, for the planar array of conductive cylinders. It shows that the TEm1 mode of the conductive waveguide and the TEm1 mode of the hypothetical waveguide are parallel. (b) The block diagram proposes the modal field decomposition and an analytical model for one planar array of cylinders, with line arrows indicating the power transmission paths from one side of the array to the other. The diagram does not show the reverse arrows for reflected power from the blocks. Each block is a 2-port. The assigning power constant of each path has been indicated below its line arrow.

Finally, six distinct paths exist that primarily transmit electromagnetic power from one side of the array to the other. They are represented by their scattering [S] and transmission [T] matrices. These paths (major modes) include the TE11, TE21, TE31, and TE41 waveguide modes, the parallel wire transmission line, and the short circuit termination. Figure 4b illustrates the modal field decomposition and the six distinct paths. The arrows indicate the power transmission paths from one side of the array to the other. The reverse arrows, which illustrate reflected power from the blocks, are not shown.

The total transmitted power from the array is the summation of the power portion transferred by each path (mode). On the other hand, the power portion transferred by each path can be calculated using a simple circuit model. The power of the incident wave to the array is divided among these six distinct paths. The power assigned to each path is the power that is available from the source for that path (source’s available power or Pavs). The ratio of the source’s available power for the ith path to the incident power is a constant that is called the “assigning power constant” of the path, as expressed in Eq. (1). It is represented by τi for the ith path where \({1}\le {i}\le {6}\). The summation of all assigning power constants is equal to 1, presented in Eq. (2), and the summation of all six different source available powers \(P_{avs}^{i}, {1}\le {i}\le {6}\), is equal to the total source available power. In Fig. 4b, the assigning power constant of each path is indicated under its corresponding line arrow.

The assigning power constants \(\tau _{i} ,~\;1 \le i \le 6\), are determined using the mode-matching technique in each frequency. Estimating these constants involves solving theoretical problems where a TEM incident wave is assumed to travel to the intended transmission line in half space. The reflection and transmission constants corresponding to that transmission line are estimated, and then the assigning power constants are elicited. They are named ‘constant’ because for a conductive cylinder with a specific radius, number of turns, and pitch angle, the value of τi, 1 ≤ i ≤ 6, remains constant at each frequency.

Example: transmitted power calculation for the planar array of cylinders

The transmitted power from each path should be calculated by the equivalent circuit, demonstrated in Fig. 5a, with a 2-port model of that path, which is terminated by a ZL = 120π load as the free space intrinsic impedance for \({z}\text{ < -}{{d}}\text{/2}\) half-space. The equivalent circuit is excited by a voltage source with a source impedance ZS = 120π as the free space intrinsic impedance for \({z}\text{ > }{d}\text{/2}\) half-space.

(a) This circuit model represents each path that the power travels through from one side of the slab to the other. A 2-port corresponds to each possible path of the unit cell of the planar array, specified by its scattering matrix [S]. There are six distinct paths among which the total incident power is distributed. (b) The time-averaged power density of the transmitted wave of the infinite periodic planar array of cylinders. The total time-averaged power density of the incident wave is assumed to be 1 W/m2 = 0 dBW/m2.

The next step involves calculating the transducer power gain (GT) for each possible path from the source to the load using its equivalent circuit. To achieve this, the scattering matrix [S] of the total block corresponding to each of the six possible paths should be calculated. The reference impedance is assumed to be 120π or 377Ω, which means that the transducer power gain of the block is equal to |S21|2. Equation (3) demonstrates how to calculate the transducer power gain. Based on the reference impedance of 120π, the reflection coefficients ΓL, ΓS, and Γin are also calculated.

The power delivered to the load by each of the six possible paths can be obtained by Eq. (4). These power values represent the amount of power transmitted from the source to the load by a specific path among all 6 possible paths.

Finally, the total power delivered to the load at each frequency can be calculated by summing the power transmitted by each of the six possible paths, as shown in Eq. (5). This amount of power is equal to the total transmitted power from one side of the array to the other side. This procedure is repeated for each frequency within the desired band.

A single-layer planar array of conductive cylinders with a radius of \({a}=\text{12 mm}\), conductor thickness of \({\delta} =\) 0.48 mm, waveguide length of \(d=\) 18 mm, and a unit cell size of 25 \(\times\) 25 mm2 was used to evaluate the proposed method. Line graph II in Fig. 5b illustrates the results of the proposed analytical method. The full-wave computer simulation result is also presented for comparison. The "Methods" section provides a thorough explanation of the full-wave simulations, excitation, and boundary conditions. Figure 5b demonstrates that the proposed model provides an acceptable estimation of the full-wave simulation result, following its general trend. The main and secondary resonance frequencies are estimated with acceptable precision.

Modal field decomposition for a planar array of helices

The particle’s geometry and position in the unit cell of the infinite periodic planar array of helical particles have been shown in Fig. 1c and d. The axis of the helical particle in a unit cell of the array is parallel to the direction of incident wave propagation and the z-axis of the universal coordinate system. Because of the strong correlation between their electric and magnetic fields and surface current patterns, the modal field decomposition process for the planar array of helical particles should be almost similar to that for the planar array of cylinders. However, the array of helices includes another primary mode, which the cylinders’ array does not. This mode, which can significantly transmit power from one side of the array to another, should be considered in the modal field decomposition process and analytical model. The new mode runs parallel to the other waveguide modes mentioned earlier due to the similarity in their electric and magnetic field patterns, directions, and polarization, shown in Fig. 6a, compared to Fig. 4a. This new mode will be described in more detail. The remaining procedures of the proposed method are implemented as previously detailed for a planar array of cylinders.

(a) The desired 2-port for TEm1 waveguide mode, m = 1,2,3,4, for the planar array of helical particles. (b) The block diagram proposes the modal field decomposition and an analytical model for one planar array of helices, with line arrows indicating the power transmission paths from one side of the array to the other. The diagram does not show the reverse arrows for reflected power from the blocks. Each block is a 2-port. The assigning power constant of each path has been indicated below its line arrow.

The transmission modes of helical-shaped particles

Consider a helical antenna excited by a coaxial cable, which has been studied in many well-known references38,39,40. There are two types of operating modes: radiation modes and transmission modes. Although the radiation modes have been widely studied in many sources and used in various applications38,39,40, the transmission modes have received less attention. However, some references studied the helically shaped conductor’s transmission modes38,41. The electromagnetic wave travels along the helix axis in transmission modes, similar to a transmission line. Depending on the operating frequency, the different transmission modes are labeled T0, T1, T2, etc.

The T0 mode occurs in the low-frequency range. The next transmission mode is T1, which is the first-order mode. Transmission mode propagation is possible when the helix relative circumference \(C_{\lambda }\) is approximately equal to 1 \(({\text{C}}_{\lambda}\approx {1})\), for a helical particle with a slight pitch angle \({\alpha}<{15}^{\circ }\). Our proposed analytical model considers the relative circumference range of \(\text{0.6}\le {\text{C}}_{\lambda}<{1}\) for T1 transmission mode propagation. In an infinite medium filled with the desired host dielectric (concrete in our application), the ratio of the helix circumference C to the wavelength λ is represented using a subscript λ, such as \({\text{C}}_{\lambda } = {\text{C}}/\lambda\), called the relative circumference. Similarly, the higher-order transmission modes T2, T3, and T4 are possible when \({\text{C}}_{\lambda}\) is increased.

Figure 7a-c illustrate the approximate instantaneous electric charge and field configurations of helix transmission modes T1, T2, and T3 38. The similarity between these electric field patterns and the electric field patterns of circular waveguide TE11, TE21, and TE31 modes is considerable. Namely, Fig. 2a-d compares the electric field configurations of a 7-turn Helix and a circular waveguide on an identical cross-section of both arrays below and beyond the TE11 mode cutoff frequency. The cross-section is parallel to the array plane and perpendicular to the incident wave propagation direction. It can be seen that the electric field pattern and directions in both structures are almost the same. Thus, an incident electric field, which can excite the waveguide modes, can also excite the helix transmission modes. It should be noted that all of the field patterns, Fig. 2a-d, are related to TE11 mode, except Fig. 2c which is related to T1 transmission mode. The circular polarization of the fields within the helix structure indicates that it is exclusively related to the helix T1 transmission mode, and it is distinguishable from the other complex patterns of the fields within a cross-section of the array of helical particles. As previously stated, the incident wave excites both TE11 waveguide and T1 transmission modes simultaneously, and they should be assumed to be parallel paths. A similar approach is valid for the other three high-order modes, TEm1 and Tm. Figure 6a illustrates the 2-port related to the Tm and TEm1, m=1,2,3,4, modes in the proposed method for an array of helical particles, compared with Fig. 4a for the array of conductive cylinders. Furthermore, Fig. 6b illustrates the mode decomposition for the array of helices. The assigning power constants τ1, τ2, τ3, and τ4 remain permanent in comparison with the array of cylinders’ mode decomposition. It means that their values in the proposed method for the array of cylinders will be identical to those in the proposed method for the array of helices at each frequency. However, the value of τ5 in the latter model is related to its value in the former model by the volume fraction of the helical conductor to the cylindrical conductor.

Moreover, it is necessary to determine the phase constant and characteristic impedance of the transmission modes. A straightforward approach for estimating the transmission modes’ phase velocity has been previously proposed38. This method considers the helix as a linear array of n isotropic point sources, where n represents the number of turns and S represents the distance between the sources, equal to the spacing between helix turns. Also, L represents the length of one turn of the helix, and pm represents the phase velocity of the mth order transmission mode Tm. The transmission line relative phase velocity is expressed as Eq. (6)38. The relative phase velocity is defined as \({p}_{m}={v}_{m}/{c}\) , where vm is the phase velocity, and c is the speed of light in free space.

Finally, the phase constant of the transmission modes can be obtained using \(\beta _{{\text{m}}} = \omega /v_{{\text{m}}}\).

The impact of the transverse magnetic field on the transmission modes excitation

It is important to note that the response of the infinite periodic planar array of helices resonates throughout the operating frequency range of the T1 and at the beginning of the operating frequency range of the T2 helix transmission modes, where the wavelength is approximately equal to the circumference of the helical particle. The behavior of the array in its resonance frequency range is primarily influenced by the nature and characteristics of these transmission modes, as the attenuation of the paths corresponding to waveguide modes is significantly high in this frequency range. Moreover, the main factor for the excitation of helix transmission modes is the magnitude of magnetic flux passing through the helical surface. The helical surface is defined as the locus of line segments connecting a point on the helix curve to the helix axis (perpendicular to it). The desired helical surface (s) is shown in Fig. 7d. The magnetic flux should be estimated to assess the transmission modes’ excitation.

As previously stated, the TE11 mode is the primary waveguide mode for transmitting power through the array. Therefore, it is necessary to select and analyze the magnetic flux of the transverse component of this mode. The helical surface has zero magnetic flux for the ρ component of the magnetic flux density, and only the φ component requires analysis. Bφm1 represents the magnetic flux density’s φ component for the TEm1 mode in a circular waveguide. Equation (7) expresses the magnetic flux for the TEm1 waveguide mode.

The normalized magnetic flux can be derived as shown in Eq. (8) after performing the necessary mathematical operations, estimating the integration with respect to the ρ coordinate, and simplifying the results. In Eq. (8), \({B}_{{0}{\varphi}}^{{m}{1}}\) is a constant, m represents the order of the TEm1 mode, and ρ, φ, and z are the coordinates of the cylindrical coordinate system. Additionally, b is the attenuation constant of the TEm1 mode in the below cutoff condition.

Moreover, the undefined variables in Eq. (8) are expressed in Eqs. (9) and (10).

A larger absolute value of the normalized magnetic flux of the TEm1 mode results in a greater amount of power being passed through the helix by the transmission mode Tm and consequently represents more transmitted power from the array in the Tm operating frequency region.

Because of the similarity between the helix transmission mode Tm and the waveguide mode TEm1, it can be assumed that the formulation of the Tm mode’s wave impedances is approximately similar to the TEm1 mode’s wave impedance. Therefore, we attempted to estimate the Tm transmission mode wave impedance using the prevalent relation \( {Z}_{m} = \omega \mu /\beta _{{m}}\). Furthermore, we have introduced a coefficient ζ0(m) into the equation, resulting in \(Z_{m} = ~\zeta _{0}^{{(m)}} \times \omega \mu ~/~\beta _{m}\). The coefficient ζ0(m) is defined using the absolute value of the normalized magnetic flux (Φn(m)) and is calculated as \(\left| {\varPhi _{{n}}^{{(m)}} \left( {\varphi = \varphi ^{0} } \right)\left| / \right|~\varPhi _{n}^{{(m)}} } \right|\max\) for a unit cell that includes one helical particle with its wire starting point at position φ = φ0.

Transmission modes’ conduction and dielectric losses

Similarly, perturbational methods can be utilized to estimate the attenuation constants of conduction and dielectric losses for the Tm transmission modes of a helical particle. For evaluating the conduction loss, the relation \((\alpha _{c} )_{m} = (P_{c} /l)/(2P_{m} )\) is utilized, which has been used in many references to estimate the attenuation constant of cylindrical and rectangular waveguide modes42. Therefore, the first step is to calculate Pc and Pm.

Pm represents the time-averaged power that passes through a particular cross-section of the transmission line. The time-averaged power passing through the transmission line can be easily calculated by \({{P}_{m}}={\text{Re}}\{({1}/{2}){\text{V}}{\text{I}}^{*}\}.\) It is assumed that V and I represent the voltage and current at the beginning of the transmission line, respectively, and that Zc is the transmission line’s characteristic impedance.

The next step involves calculating the term Pc / l, where Pc represents the dissipated power resulting from the finite conductivity of the helical particles’ wire. The wire diameter is much smaller than the wavelength, so the current flows along the wire conductor without any considerable radial components. To estimate the dissipated power of the surface current, the common relations can be used to derive Pc and Pc / l 42. Since the effective length is used to estimate the length of the helix transmission modes, leff replaces the denominator. Finally, αc can be expressed as Eq. (11).

The attenuation constant αd for dielectric losses can be estimated using the method described in many references for cylindrical or rectangular waveguides filled with a lossy dielectric material42. In the following relations, parameters with prime index refer to the lossy condition, while parameters without prime index refer to the lossless condition. Thus, Eq. (12) represents the dispersion equations for both conditions in a cylindrical coordinate system, assuming the wave propagates along the z-axis.

where β and β′ are the traveling wave phase constants in the unbounded dielectric medium in lossless and lossy conditions, respectively. Similarly, βz and β′z are the phase constant of the wave traveling in a cylindrical structure, such as a helix, in the z-direction. Based on the perturbational method, it can be presumed that β′ρ2= βρ2. Hence, Eq. (13) can be derived by replacing β′ρ2 in Eq. (12) with β′ρ2= βρ2= β2− βz2.

Now, β′z is a complex value, and its imaginary part can be an estimation of the dielectric attenuation constant αd, as expressed in Eq. (14). Finally, the total attenuation constant α for the Tm transmission mode of the helical particle is the sum of the dielectric losses attenuation constant αd and the conduction losses attenuation constant αc.

Example: transmitted power calculation for the planar array of helices

A concrete composite material containing a single-layer planar array of helical particles was numerically simulated and experimentally fabricated to validate the proposed analytical method. The full-wave simulations, excitation, and boundary conditions, along with the specifics of the manufacturing process, testing setup, and measurement procedures, are comprehensively outlined in the "Methods" section. The helix has a diameter of \({D}=\text{24 mm}\), a conductive wire diameter of \({d}=\text{0.48 mm}\), a spacing between turns of \({s}=\text{6 mm}\), a pitch angle of \({\alpha}={4.55}^{\circ }\), \({n}=\text{1.5}\) turns, and an axial length of \({L}={n.S}={9}\) mm. The unit cell size has been determined as A \(\times\) A = 25 \(\times\) 25 mm2, resulting in a dense array. The transmitted power calculation method is the same as that which was explained for a single-layer planar array of cylinders.

Two different geometries of this helical particle have been investigated, resulting in two distinct arrays. The helix particle’s starting point of the wire is on the x-axis in the first array and the y-axis in the second. These arrays are respectively shown in Fig. 8a and c. The outcomes of these two arrays are respectively demonstrated in Fig. 8b and d, indicating that the proposed method closely follows the trends of the full-wave simulation and experimental measurement results and provides an acceptable approximation. In particular, the proposed method can capture the anti-resonance peak, Fig. 8b, although the error is evident. The cause of this error is the structure’s complexity, making it difficult for the simple proposed method to capture it precisely. However, it can explain the nature of the anti-resonance behavior, predict its existence, and approximate its frequency region at around \({f}=\text{1.5 GHz}\) in Fig. 8b. To understand the cause and nature of this behavior, the normalized magnetic flux for T1 transmission mode, Eq. (8), should be calculated. The calculated normalized magnetic flux for the helical particle shown in Fig. 8a increases across the frequency range of 1.1 to 1.5 GHz and reaches the value of 3.94 (10−3Wb/m) at \({f}=\text{1.5 GHz}\), while for the helical particle shown in Fig. 8c, the normalized magnetic flux decreases across the aforementioned frequency range and reaches the value of 0.54 (10−3Wb/m) at \({f}=\text{1.5 GHz}\), which is considerably lower than the former. The higher value of the normalized magnetic flux’s magnitude corresponds to higher excitation of the helix transmission line and, thus, higher transmitted power through the array. At frequencies around 1.5 GHz, the T2 transmission mode starts to be excited, and the T1 transmission mode approaches the end of its operating frequency region. However, the TE21 waveguide mode carries only a tiny portion of the total power. As a result, it cannot effectively excite the T2 transmission mode and deliver a significant amount of power to it. Therefore, in the frequency range above 1.5 GHz, the transmitted power from the array decreases as the frequency increases. Hence, the anti-resonance trend in Fig. 8b can be explained by the absolute value of the normalized magnetic flux.

The unit cell of the infinite periodic planar array of helices and its corresponding time-averaged power density of the transmitted waves. (a) The helical particle’s starting point of the wire is in position φ = − 180°. (b) The transmitted power for (a). (c) The helical particle’s starting point of the wire is in position φ = − 90°. (d) The transmitted power for (c). (The blue transparent cube represents the surrounding concrete material as the host medium. The total time-averaged power density of the incident wave is assumed to be 1 W/m2 = 0 dBW/m2.)

Additionally, it is essential to note that the similarity between the general trends of the results of an array of helical particles and an array of conductive cylinders, shown in Fig 5b, as well as the similar main resonance frequency region, indicates a close relation between the natures of these arrays.

Transmitted power calculation for multi-layer array of helices

Figure 1a and b show an example of the unit cell and its geometry of the intended multi-layer array. The array consists of several parallel planar arrays of helical particles embedded in a concrete host medium. The size of the helical particles of each infinite periodic planar array can be different from another. Fig. 9a shows the different layers of the 6-layer array illustrated in Fig. 1a, numbered 2 to 14. Even numbers represent pure concrete areas (without any conductive particles), while odd numbers represent planar arrays consisting of helices. The mathematical model for the multi-layer array involves cascading distinct planar arrays, each of which can be analyzed mathematically.

(a) The different layers of the 6-layer array. (b) The possible path for even layers that are made of pure concrete without conductive particles. (c) The possible sub-paths for each planar array of helical particles. (d) This circuit model represents each path that the power travels through from one side of the slab to the other. A 2-port corresponds to each possible path of the unit cell of the 6-layer array, specified by its scattering matrix [S]. There are 66 distinct paths among which the total incident power is distributed.

Each planar array can be mathematically modeled by six distinct paths for power transmission from one side to the other, as shown in Fig. 6b. Each of these six paths is called a “sub-path” in this section to distinguish it from the possible general paths from one side of the slab to the other (or from source to load in the equivalent circuit). Figure 9c shows these possible sub-paths for each planar array of helices. In contrast, the even layers in Fig. 9a, made of pure concrete, can be modeled by only one path for power transmission, as illustrated in Fig. 9b. This path is a transmission line characterized by the propagation constant γ and characteristic impedance Z, which are the characteristics of the unbounded medium filled with concrete. Moreover, the lengths of the odd layers are estimated based on their effective length, while the lengths of the even layers are determined by their physical length.

For each frequency, there are \({6}^{6}\) distinct paths from the source to the load or from one side of the 6-layer array to the other side. These paths can be represented by superscript \(j^{{(3)}} j^{{(5)}} \ldots j^{{(13)}}\) where \(j^{{(i)}} = 1, \ldots ,6\) is the sub-path number of the ith layer. Each path can transmit a portion of the total incident power to the other side of the slab. As a result, the total available power is divided between the different possible paths. Although the problem is complex, simplifying assumptions can reduce its complexity. It is assumed that all possible paths are independent of each other. Figure 9d illustrates the equivalent circuit model for each of these potential paths.

The total incident power or total source’s available power, Pavs(2), is distributed among these possible paths at each frequency. The source’s available power of the \({6}^{6}\) different possible paths can be obtained by multiplying the assigning power constant of the corresponding sub-path of every layer from source to load. Furthermore, the assigning power constant of each layer with an even number (τ7) equals 1. Equation (15) demonstrates the calculation of the source’s available power Pavs of each path.

The next step involves calculating the transducer power gain (GT) for each of the \({6}^{6}\) possible paths from source to load. To achieve this, the transmission matrix [T] of the total block corresponding to each possible path should be calculated. It can be derived by multiplying the transmission matrices [T] of the selected sub-path in every layer for each of the \({6}^{6}\) possible paths. This will allow us to obtain that block’s scattering matrix [S]. The reference impedance is assumed to be 120π or 377Ω, which means that the transducer power gain of the block is equal to |S21|2. Equation (16) demonstrates how to calculate the transducer power gain. Based on the reference impedance of 120π, the reflection coefficients ΓL, ΓS, and Γin are also calculated.

The power delivered to the load by each of the \({6}^{6}\) possible paths can be obtained by Eq. (17). These power values represent the amount of power transmitted from the source to the load by a specific path among all 66 possible paths.

Finally, the total power delivered to the load at each frequency can be calculated by summing the power transmitted by each of the 66 possible paths, as expressed in Eq. (18). This procedure is repeated for each frequency within the desired band.

We developed and utilized a MATLAB script to implement the proposed analytical method. Figure 10b displays the flowchart of the script for each frequency in the desired frequency band.

(a) The possible sub-paths for each planar array, one of which is selected by the flowchart for every planar array in each loop. Two solid purple and dashed red lines have shown two possible paths from source to load. (b) The MATLAB script’s flowchart for the proposed analytical method for the multi-layer array in each frequency. A similar flowchart has been used for single-layer planar arrays.

Example: the transmitted power through a 6-layer array of helices

In this section, the results of the MATLAB script, full-wave computer simulation, and experimental measurement are compared to assess the authenticity of the proposed method. The features of the full-wave simulations, excitation, and boundary conditions, as well as the details of the manufacturing process, test setup, and measurement procedure, are thoroughly described in the "Methods" section. Figure 1a and b illustrate the geometry and unit cell of the 6-layer array of helices. Table 1 presents the specifications of the particles of different layers. Figure 11a furthermore depicts the thickness and position of the different layers of the 6-layer array.

(a) The thickness of the different layers in the 6-layer array. (b) The time-averaged power density of the transmitted wave through the helical particle 6-layer array whose unit cell is shown in Fig. 1. The total time-averaged power density of the incident wave is assumed to be 1 W/m2 = 0 dBW/m2.

Figure 11b displays the results for the proposed method, full-wave simulation, and the experimental measurement for the 6-layer array. The proposed method results align with the full-wave simulation and experimental measurement results in the resonance frequency range (below 4.5 GHz), with an acceptable deviation. However, in the high-frequency range, namely beyond 4.5 GHz, since the structure is modeled by some transmission lines that transfer the electromagnetic power from one side of the array to another and the wavelength is short compared to the thickness of the array, it is predictable that some ripples (up and down behavior) can be observed in the results of the proposed method because of the nature of transmission lines. Additionally, Beyond the frequency of 4.5 GHz, high order modes and other complicated modes that do not exist in the array of cylindrical waveguides’ model propagate through the multi-layer array. The propagation of these sophisticated modes results in a deviation beyond 4.5 GHz. However, the proposed method still follows the trend of the simulation and experimental results. It also demonstrates significant attenuation in transmitted power from the array over a wide frequency range. For instance, the attenuation reaches 60 dB at a frequency of 3.5 GHz and between 55 and 60 dB in the frequency range from 2.5 to 3.5 GHz. The composition is, therefore, appropriate for EMI shielding applications. The results show that a multi-layer array of helical particles with the aforementioned structure can achieve remarkable shielding effectiveness in a wide frequency band.

Given the strong agreement between the full-wave simulation results and the experimental measurements under normal incidence conditions (Fig. 11b), the full-wave simulation method can be effectively utilized to evaluate the shielding properties of the slab, including a 6-layer array, under oblique incidence of a uniform plane wave (a realistic scenario.) In order to assess the shielding performance of the helical particle array shown in Fig. 11a against oblique incidence, six full-wave simulations were conducted. The incident wave angles were selected as follows: (φ = 0○, θ = 20○), (φ = 90○, θ = 20○), (φ = 0○, θ = 40○), (φ = 90○, θ = 40○), (φ = 0○, θ = 60○), and (φ = 90○, θ = 60○). Each angle included two polarization types:

-

1.

Perpendicular (horizontal or E) polarization, where the electric field of the incident wave is parallel to the slab interface, as illustrated in Fig. 12a.

-

2.

Parallel (vertical or H) polarization, where the magnetic field of the incident wave is parallel to the slab interface, as shown in Fig. 12b.

(a) Perpendicular (horizontal or E) polarization incident at oblique angles on the slab interface. (b) Parallel (vertical or H) polarization incident at oblique angles on the slab interface. (c) The time-averaged power density of the transmitted wave through the helical particle 6-layer array, whose unit cell is shown in Fig. 1, for the E polarization incidence. (d) The time-averaged power density of the transmitted wave through the helical particle 6-layer array, whose unit cell is shown in Fig. 1, for the H polarization incidence. The total time-averaged power density of the incident wave is assumed to be 1 W/m2 = 0 dBW/m2.

Figure 12c and d present the results for transmitted power through the array for E-polarized and H-polarized incident waves, respectively. These results demonstrate that the shielding performance and transmitted power of the slab remain approximately consistent across all incident angles, directions, and polarizations of the wave. Furthermore, a comparison between Fig. 11b and Fig. 12c and d shows negligible variation in transmitted power and the array’s resonance frequency region across the frequency band of interest, regardless of the incident wave’s direction or polarization. This uniform shielding performance is a critical characteristic of composite materials used in EMI shielding applications. Additionally, the similarity between the oblique incidence results and those of normal incidence suggests that the proposed analytical method can effectively predict the shielding properties of the helical particle array. This insight facilitates the design and optimization of composite materials for EMI shielding purposes.

In addition, full-wave simulations, which rely on numerical calculations and are computationally intensive, require robust hardware and extended computational time. Similarly, experimental measurements require significant human resources, extensive and time-consuming preparation, and high costs. To balance accuracy with efficiency, we prefer to accept a slight degree of inaccuracy to reduce the computational load, cost, and time associated with evaluating the composite structure. The proposed method allows for efficient estimation of the response of the designed structure in a short time. Consequently, it can be applied to optimize the array and the concrete composite design for EMI applications. Table 2 shows the total solving time and peak memory usage for the full-wave simulation with a frequency domain solver (F solver) and the proposed method, respectively, executed using CST Studio Suite software and a MATLAB script. To ensure a fair comparison between the proposed method and the full-wave simulation, we reduced the tetrahedral mesh count by altering the helices’ wire cross-section geometry from circular to a regular 10-sided polygon, deactivating adaptive mesh refinement, and increasing the threshold for the interpolative frequency sweep in CST Studio Suite software. The simulations were conducted using an Intel Core i9-9900K processor with 128 GB of RAM. According to Table 2, the superiority of the proposed method over full-wave simulation in different conditions is evident in solving time and peak memory usage, owing to its simplicity.

Discussion

The helical particles in a planar array can imitate a below-cutoff cylindrical waveguide and its dominant mode surface current on the helical wire, leading to evanescent wave propagation. This property significantly attenuates the transmitted power from the array of helical particles in its resonance frequency range. This phenomenon occurs below the TE11 mode cutoff frequency of a cylindrical waveguide with a radius similar to that of the helical particle. In the case of planar arrays, the center frequency in the main resonance region is the frequency whose wavelength in the host medium is almost equal to the circumference of the helix particle located in the unit cell of the array \((C_{\lambda } \approx 1)\). Moreover, the multi-layer array of helical particles can effectively reduce the transmitted power, reaching -60 (dBW/m2) with the 6-layer array, and increase the slab’s shielding effectiveness across a broad frequency range. The experimental measurement results have validated two key aspects: first, the significant attenuation observed in the array’s resonance frequency region, and second, the accuracy of the proposed analytical and full-wave simulation results. Furthermore, the structure can be expanded to suit the desired application or frequency band.

The study proposes a method that utilizes a circuit model to simplify and analyze a complicated structure and provides acceptable outcomes. The method has a significantly low computational load due to its basis in a circuit model, which allows it to be processed very quickly. The proposed method is beneficial for optimizing various shielding structures that consist of concrete composite designs for EMI applications. The main limitation of the proposed method is the geometry of the helices, which can be outlined as: 1- a pitch angle lower than approximately 8 degrees to guarantee the imitation of cylindrical waveguide TE11 mode. 2- a very small thickness of the helix’s wire in comparison with wavelength. 3- dense array, which means the adjacent particles must be very close.

From one perspective, arranging helical particles in an array can reduce the required additives while improving the shielding effectiveness of the composite. Hence, this paper proposes and analyzes a system of particles arranged in a regular array and embedded within a concrete slab. On the other hand, the present work is the first step in developing an analytical method for analyzing and estimating the transmitted power of general structures, including concrete composites, which incorporate randomly distributed helical particles with different sizes as additives. The ultimate goal of this research is to provide a comprehensive understanding of the role played by these additives in enhancing the structural integrity, durability, and electromagnetic shielding properties of concrete composites, which can have numerous applications in the construction industry.

Methods

Full-wave simulations

CST Studio Suite software performed all of the full-wave simulations in this work. In CST Studio Suite software, full structures cannot be simulated due to the infinite cross-section of the slabs; instead, a unit cell of the structure with periodic boundary conditions is used. The selected section of the slab contains a unit cell of the array of helical particles embedded in concrete material. Two ports are placed on either side of the slab. Port 1 is excited, and the total power delivered to Port 2 is measured. A Floquet port is implemented to excite the unit cell, and the frequency domain solver (F solver) utilizes the Method of Moments (MoM) for simulation. To provide the periodic boundary condition, the Floquet method considers the two structure’s walls, which are perpendicular to the incident electric field, as perfect electric conductor (PEC) walls, and two other walls, which are parallel to the incident electric field, as perfect magnetic conductor (PMC) walls. We used the tetrahedral mesh type to perform the simulation for the multi-layer structure made of helical particles whose wire has a regular 10-sided cross-section shown in Figure 1a and b, which included more than 1,250,000 mesh cells.

MATLAB script

The proposed method is implemented by a MATLAB script. Figure 10 displays the script’s flowchart for each frequency in the desired frequency band. A similar flowchart has been used for single-layer planar arrays.

Materials

The materials assigned to different parts of the proposed structures in both the proposed analytical method and full-wave simulation were identical. For concrete material, we used a dispersive, complex, and 1st-order model for relative electric permittivity \(({\varepsilon}_{\text{r}})\). Its value was equal to \({\varepsilon}_{\text{r}}=\text{5.5}-\text{0.02i for }{f}\text{=1.36 (GHz)}\), \(\text{5.5}-\text{0.12i for }{f}\text{=2.52 (GHz)}\), and \(\text{5.55}-\text{0.09i for }{f}\text{=3.68 (GHz)}\). The relative magnetic permeability was equal to 1 \((\mu _{{\text{r}}} = 1)\). In addition, the material assigned to the metal parts, such as conductive cylinders and helical particles, was iron with \({\varepsilon }_{\text{r}}\text{=}1\), \({\mu}_{\text{r}}= \text{4000}\), and the electric conductivity \(\sigma = 1.03 \times {\text{e}} + 07{\text{ }}({\text{S}}/{\text{m}})\).

Manufacturing experimental samples

To validate the results of the proposed analytical method and full-wave simulations, experimental measurements have been conducted for the proposed structures, described in Fig. 8a, b, and Fig. 11a. To this end, we manufactured two reinforced concrete composite samples with cross-sectional dimensions of 40×40 cm2. The first sample, with a thickness of 3.5 cm, includes a single planar array of 1.5-turn helices, as depicted in Fig. 1d or Fig. 8a and b. The second sample, with a thickness of 10.5 cm, comprises a six-layer array of 1.75-turn helices, as shown in Fig. 1a and b or Fig. 11(a).

To ensure consistency, the geometry and dimensions of the helical particles used in the experimental samples matched those employed in full-wave simulations and the proposed analytical method, as detailed in Table 1 for the 6-layer array. All components were constructed from steel. Figure 13 shows the manufacturing process of the reinforced sample with a thickness of 3.5 cm, including a single-layer array of 1.5-turn helices. Figure 14 illustrates the manufacturing process of the reinforced sample with a thickness of 10.5 cm, comprising a 6-layer array of helical steel particles. Each helical particle includes 1.75-turn helices and an additional ring (a helix with zero pitch angle) at one end. Figure 14a shows the six different helical particles corresponding to each layer (planar array) for the 6-layer structure presented in Figs. 1a and 11a. The helical particles for each layer were mounted on plastic mesh nettings and fixed with spray adhesive. These planar arrays of helices mounted on plastic mesh nettings are shown in Figs. 13b and 14b, respectively, for a single-layer array and a 6-layer array. Each layer was then positioned within a mold, and concrete paste was poured to form slabs with dimensions of 40×40×3.5 cm3 (Fig. 13e including single-layer array) and 40×40×10.5 cm3 (Fig. 14d including a six-layer array).

The manufacturing process of the reinforced sample with a thickness of 3.5 cm, including a single-layer array of 1.5-turn helices: (a) The 1.5-turn helical steel particle. (b, c) The planar array of helices mounted on a plastic mesh netting with dimensions \({40}\times {40}\) cm2. (d) Securing the array in its position within the mold. (e) The reinforced concrete composite after the drying process.

The manufacturing process of the reinforced sample with a thickness of 10.5 cm, including a 6-layer array of 1.75-turn helices: (a) six different sizes of the 1.75-turn steel helix (plus one ring at one end.) (b) Six planar arrays of 1.75-turn helices mounted on plastic mesh nettings with dimensions \({40}\times {40}\) cm2. (c) Securing the arrays in their position within the mold. (d) The reinforced sample (concrete composite material) after the drying process.

Experimental measurements

After drying, the shielding property of the slabs was measured using the test setup and the iron shelter, illustrated in Fig. 15a and b, over a frequency range of 0.75 to 12 GHz in 0.25 GHz intervals (Frequency intervals of 0.1 GHz between 0.8 and 2.1 GHz for the sample with a thickness of 3.5 cm.) The measurement process for each sample was conducted under two conditions. (1) Loaded condition: The excitation aperture of the test setup had been covered with the concrete slab, and the transmitted power was measured as \({P}_{\text{Loaded}}\). (2) Through condition: The excitation aperture of the test setup was open (not covered), and the transmitted power was again measured as \({P}_{\text{Loaded}}\). In order to eliminate the effect of the shelter and test setup on the value of the transmitted power, these two measured powers must be subtracted from each other. Hence, the transmitted power from the slab can be derived by \({{P}_{\text{T}}}= {{P}_{\text{Loaded}}}\text{ (dB)}-{{P}_{\text{Through}}}\text{ (dB)}\).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mardiguian, M. & Caron-Fellens, J. P. The intelligent concrete: A new, economical technique for architectural shielding of buildings. IEEE Electromagn. Compat. Mag. 6(2), 50–54 (2017).

Quintana, S. et al. Design and operation of a real-scale electromagnetic shielding evaluation system for reinforced composite construction materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 30(8), 04018162 (2018).

Keykavous-Amand, S. & Peymanfar, R. Fabrication of clay soil/CuFe2O4 nanocomposite toward improving energy and shielding efficiency of buildings. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 20832 (2021).

Peymanfar, R., Keykavous-Amand, S., Abadi, M. M. & Yassi, Y. A novel approach toward reducing energy consumption and promoting electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency in the buildings using Brick/polyaniline nanocomposite. Constr. Build. Mater. 263, 120042 (2020).

Johns, D. Designing building structures for protection against EMP and lightning. IEEE Electromagn. Compat. Mag 5(1), 50–58 (2016).

Roberts, J., Ford, K. L. & Rigelsford, J. M. Secure electromagnetic buildings using slow phase-switching frequency-selective surfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 64(1), 251–261 (2015).

Kawase, T. & Tanoi, J. Reinforced concrete partition body. U.S. Patent 0 324 811 (2012).

Tuan, C., Nguyen, L. & Chen, B. Concrete mix for electromagnetic wave/pulse shielding. U.S. Patent 8 968 461 (2015).

Ängskog, P., Bäckström, M., Samuelsson, C. & Vallhagen, B. K. Shielding effectiveness and HPM vulnerability of energy-saving windows and window panes. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 61(3), 870–877 (2018).

Khalid, T., Albasha, L., Qaddoumi, N. & Yehia, S. Feasibility study of using electrically conductive concrete for electromagnetic shielding applications as a substitute for carbon-laced polyurethane absorbers in anechoic chambers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 65(5), 2428–2435 (2017).

Wanasinghe, D., Aslani, F. & Ma, G. Electromagnetic shielding properties of carbon fibre reinforced cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 260, 120439 (2020).

Liu, Z., Ge, H., Wu, J. & Chen, J. Enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding of carbon fiber/cement composites by adding ferroferric oxide nanoparticles. J. Constr. Build. Mater. 151, 575–581 (2017).

Micheli, D. et al. Electromagnetic characterization and shielding effectiveness of concrete composite reinforced with carbon nanotubes in the mobile phones frequency band. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 188, 119–129 (2014).

Singh, A. P. et al. Multiwalled carbon nanotube/cement composites with exceptional electromagnetic interference shielding properties. J. Carbon 56, 86–96 (2013).

Nam, I. W., Kim, H. K. & Lee, H. K. Influence of silica fume additions on electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of multi-walled carbon nanotube/cement composites. J. Constr. Build. Mater. 30, 480–487 (2012).

Chen, J., Zhao, D., Ge, H. & Wang, J. Graphene oxide-deposited carbon fiber/cement composites for electromagnetic interference shielding application. J. Constr. Build. mater. 84, 66–72 (2015).

Singh, A. P., Mishra, M., Chandra, A. & Dhawan, S. K. Graphene oxide/ferrofluid/cement composites for electromagnetic interference shielding application. J. Nanotech. 22(46), 465701 (2011).

Cao, J. & Chung, D. D. L. Colloidal graphite as an admixture in cement and as a coating on cement for electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Cement Concrete Res. 33(11), 1737–1740 (2003).

Cremar, L. D., Acosta-Martinez, J., Villarreal, A., Salinas, A. & Lozano, K. Mechanical and electrical characterization of carbon nanofibers produced from water soluble precursors. J. Mater. Today Commun. 7, 134–139 (2016).

Bayat, M., Yang, H., Ko, F. K., Michelson, D. & Mei, A. Electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of hybrid multifunctional Fe3O4/carbon nanofiber composite. J. Polym. 55(3), 936–943 (2014).

Hong, X. & Chung, D. D. L. Carbon nanofiber mats for electromagnetic interference shielding. J. Carbon 111, 529–537 (2017).

Wen, S. & Chung, D. D. L. Electromagnetic interference shielding reaching 70 dB in steel fiber cement. J. Cement Concrete Res. 34(2), 329–332 (2004).

Alsalami, Z. A. & Abbas, F. H. Ultra-high-performance concrete with micro-to nanoscale reinforcement. ACI Mater. J. 121(2), 73–92 (2024).

Gou, H., Zhu, H., Zhou, H. & Yang, Z. Reinforcement mechanism of orientally distributed steel fibers on ultra-high-performance concrete. J. Constr. Build. Mater. 281, 122646 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. A new orientational molding method for ultra-high performance concrete with high content of steel fiber and investigation on its flexure and axial tensile properties. J. Constr. Build. Mater. 400, 132755 (2023).

Gong, J. et al. Utilization of fibers in ultra-high performance concrete: A review. J. Compos. Part B Eng. 241, 109995 (2022).

Tretyakov, S. A., Mariotte, F., Simovski, C. R., Kharina, T. G. & Heliot, J. P. Analytical antenna model for chiral scatterers: Comparison with numerical and experimental data. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 44(7), 1006–1014 (1996).

Guerin, F., Banneller, P. & Labeyrie, M. Scattering of electromagnetic waves by helices and application to the modelling of chiral composites. I: Simple effective-medium theories. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 28(4), 623–642 (1995).

Guérin, F., Bannelier, P., Labeyrie, M., Ganne, J. P. & Guillon, P. Scattering of electromagnetic waves by helices and application to the modelling of chiral composites. II. Maxwell Garnett treatment. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 28(4), 643–656 (1995).

Hamidi, A., Cheldavi, A. & Habibnejad Korayem, A. Stochastic approach to evaluate the shielding effectiveness of composite materials loaded with randomly oriented helices. Electron. Lett. 60(21), 70016 (2024).

Yatsenko, V. V. & Maslovski, S. I. Electromagnetic diffraction by double arrays of dipole scatterers. Int. Seminar Day Diffraction. Proc., 196–209 (1999).

Yatsenko, V., Maslovski, S. & Tretyakov, S. Electromagnetic interaction of parallel arrays of dipole scatterers. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 25, 285–307 (2000).

Simovski, C. R., Belov, P. A. & Kondratjev, M. S. Electromagnetic interaction of chiral particles in three-dimentional arrays. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 13(2), 189–204 (1999).

Yatsenko, V. V., Maslovski, S. I., Tretyakov, S. A., Prosvirnin, S. L. & Zouhdi, S. Plane-wave reflection from double arrays of small magnetoelectric scatterers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 51(1), 2–11 (2003).

Kharina, T. G., Tretyakov, S. A., Sochava, A. A., Simovski, C. R. & Bolioli, S. Experimental studies of artificial omega media. J. Electromagn. 18(4), 423–437 (1998).

Niemi, T., Karilainen, A. O. & Tretyakov, S. A. Synthesis of polarization transformers. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 61(6), 3102–3111 (2013).

Hamidi, A., Cheldavi, A. & Habibnejad Korayem, A. A lightweight concrete composite material with improved EMI shielding by using a chiral particle array. AIP Adv. 14(8), 085018 (2024).

Kraus, J. D. & Marhefka, R. J. The helical antenna. In Antennas for all Applications 2nd edn 265–338 (McGraw-Hill, 1997).

Marsh, J. A. Current distributions on helical antennas. Proc. IRE 39(6), 668–675 (1951).

Kraus, J. D. & Williamson, J. C. Characteristics of helical antennas radiating in the axial mode. J. Appl. Phys. 19(1), 87–96 (1948).

Morgan, S. P. & Young, J. A. Helix waveguide. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 35(6), 1347–1384 (1956).

Balanis, C. A. Circular cross-section waveguide and cavities. In Advanced Engineering Electromagnetics 2nd edn 483–500 (Wiley, 2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.H., A.C., and A.H.K. proposed the idea. A.H. implemented the problem formulation and theoretical calculations, developed the MATLAB script, performed numerical simulations, and analyzed the results. Finally, A.H. wrote the manuscript. A.H. and M.B. reviewed the manuscript. A.C. and A.H.K. supervised the project and helped analyze the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hamidi, A., Cheldavi, A., Habibnejad Korayem, A. et al. Analytical model for helical particle array assessment for EMI shielding applications. Sci Rep 15, 2161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85818-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85818-1