Abstract

The association between the recently updated cardiovascular health (CVH) assessment algorithm, the Life’s Essential 8 (LE8), and all-cause mortality among adults with depression remains unknown. From the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) spanning 2005–2018, a cohort of 2,935 individuals diagnosed with depression was identified. Their CVH was evaluated through the LE8 score system. The investigation of mortality status utilized connections with the National Death Index up to December 31, 2019. To assess the impact of CVH on mortality risk, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and Cox proportional hazards models, adjusting for variables related to demographics and socioeconomic status, were applied. Among 2,935 participants, those with higher CVH levels had significantly lower all-cause mortality compared to those with lower CVH levels. Cox regression analyses demonstrated that each 1-point increase in CVH score was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality [HR = 0.97, 95%CI:0.96–0.98]. The inverse association between CVH and mortality persisted across different demographic and socioeconomic subgroups. Higher CVH levels were associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality in individuals with depression. These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive CVH management as part of healthcare strategies for people with depression, suggesting that improving CVH may contribute to longer life expectancy in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression, characterized by persistent sadness, lack of interest, and a variety of emotional and physical issues, significantly reduces quality of life and increases the risk of various health complications, including mortality1,2,3. As the understanding of mental health’s profound impact on overall health outcomes deepens, there is an urgent need to explore how managing concurrent health factors might affect the life quality and longevity of individuals with depression4.

Improving Cardiovascular Health (CVH) has emerged as a key strategy for enhancing survival and quality of life among vulnerable populations, including those with mental health conditions such as depression5. Evidence indicates a clear relationship between modifiable lifestyle factors—such as diet, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption—and cardiovascular disease risk6,7,8,9. Effective management of these factors offers significant potential for mitigating the cardiovascular risks associated with depression, highlighting the importance of a multifaceted approach to health risk management in individuals with depression10.

The American Heart Association (AHA) has played a crucial role in defining and promoting CVH through initiatives such as “Life’s Simple 7” (LS7) and more recently, “Life’s Essential 8” (LE8). These frameworks classify key lifestyle and health metrics, including diet, exercise, exposure to tobacco/nicotine, sleep quality, body mass index (BMI), blood lipids, blood glucose, and blood pressure11. For individuals with depression, integrating comprehensive CVH management strategies, including the LE8 criteria, may offer a pathway to significantly improve health outcomes12,13. Notably, individuals with depression often experience under-recognition or undertreatment of their cardiovascular needs compared to those without depression14,15. This may stem from various factors, such as inadequate screening of cardiovascular risk factors during mental health appointments, reduced adherence to treatment plans due to depressive symptoms, or diminished access to preventive care. Such gaps in care can heighten the risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes, underscoring the importance of a holistic approach that simultaneously addresses mental health and cardiovascular risk management16,17. Individuals with depression are at an increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases due to factors such as inflammation, autonomic dysfunction, and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors commonly associated with depression18,19. Despite the known benefits of optimal CVH in reducing mortality risk in the general population, it remains unclear whether these benefits extend to individuals with depression, who may face unique challenges in managing their health. Addressing this gap is crucial because tailored interventions that improve CVH could potentially mitigate the elevated mortality risk observed in this vulnerable group. Emerging evidence has illustrated the inverse association between CVH and depression, underscoring the importance of managing CVH levels in individuals with depression20,21. However, current research predominantly consists of cross-sectional studies that have established an association between CVH and the prevalence of depression, leaving a gap in understanding whether controlling CVH levels could reduce all-cause mortality rates among individuals with depression. Therefore, investigating the prospective relationship between CVH and mortality in individuals with depression is essential to inform integrated healthcare strategies that could enhance both mental and physical health outcomes.

The objective of the present study is to utilize the LE8 score, defined by a comprehensive strategy, to measure CVH and data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), to investigate whether CVH is associated with all-cause mortality among individuals with depression and if it can be employed as a method for managing and controlling mortality rates in daily life.

Methods

Study population

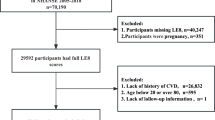

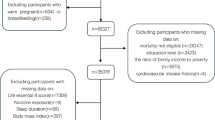

Initiated by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the NHANES serves as a nationally representative study aimed at assessing the health and nutrition of American residents22. NHANES employs a complex, multistage probability sampling design to select participants who are representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population. This design includes stratification, clustering, and oversampling of certain subgroups (e.g., persons aged 60 and over, African Americans, Hispanics) to ensure adequate representation and improve the reliability and precision of estimates for these groups23. The NHANES website offers detailed descriptions of its design and methodologies. This study utilizes data spanning from 2005 to 2018 from NHANES, along with additional insights from the NHANES Linked Mortality File, which connects participant data to the National Death Index until the end of 2019. Exclusion criteria were: (1) 297 participants with missing mortality data; (2) 2,947 participants not in 20–80 years old age range; (3) 803 individuals pregnant or breastfeeding; (4) 26,441 participants without depression or missing data on depression. Ultimately, the study incorporated 2,935 participants for analysis (Fig. 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals involved, ensuring the research complied with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting.

Flow Chart of Participant Selection. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; CVH, Cardiovascular Health. This flow chart summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria leading to a final sample of participants with depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) who had complete data for mortality follow-up, key demographic/socioeconomic information, and LE8 cardiovascular health metrics.

Depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), an established tool with nine items, evaluates the severity of depression using a scale from 0 (none) to 3 (nearly every day), allowing for a cumulative score between 0 and 2724. Achieving a score of 10 or more on the PHQ-9 signals the presence of depressive symptoms25. Depression intensity is classified into moderate (scores of 10–14) and moderately severe to severe (scores of 15 or higher) categories25.

Cardiovascular Health

The LE8 scoring system is a complex algorithm for measuring CVH, which integrates eight key components: dietary patterns, exercise intensity, smoking, sleep quality, BMI, non-HDL cholesterol, blood glucose levels, and blood pressure. Extensive information on scoring for CVH factors is available in Table S1 and referenced articles12,26,27. Individual CVH factors are scored on a 0 to 100 scale, with the overall CVH score being the average of these eight scores. The American Heart Association defines CVH levels as high (80–100), moderate (50–79), and low (0–49) based on these scores11.

Outcome definition

Data from the NHANES were aligned with records from the National Death Index up to December 31, 2019, using a probabilistic algorithm to verify mortality status. The causes of death were identified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision. All-cause mortality encompassed deaths from any cause. As mortality data were obtained through this linkage, loss to follow-up regarding mortality status was minimized, ensuring comprehensive outcome data for the participants included in our analysis28.

Covariates

Similar to previous studies, since most of the important covariate information is already included in the calculation of the CVH, among the covariates we mainly included demographically relevant covariates12,26,28. Information on demography including age, sex, race, family income to poverty ratio (PIR), educational level were collected through standard survey.

Statistical analysis

The proportion of missing data for variables used in the statistical models ranged from 0 to 21.3%. Missing data were addressed using the random forest imputation method via the ‘missForest’ package in R29, which is suitable for handling mixed-type data and has been shown to perform well in various scenarios30. This method allows for the estimation of missing values based on observed data without substantially biasing the results. CVH was classified into low (< 50), moderate (50–79), and high (80–100) according to the LE8 score methods (Table S1). Kaplan-Meier survival plots quantified the overall mortality for each CVH group (low, moderate, high). Cox regression models were deployed to investigate the association between CVH and mortality from all causes. Three models were utilized as follows: Model 1 was unadjusted for covariates; Model 2 was including age, sex, and race; Model 3 further augmented Model 2 by integrating socioeconomic factors (education level and PIR) and total PHQ-9 score. Subgroup analyses and tests for interaction examined the consistency of the association between CVH and mortality across diverse groups, including sex (male/female), age (< 60/≥60 years), family income to poverty ratio (PIR; <1.3, 1.3–3.0, > 3.0), education level (less than high school, high school, more than high school) and depression severity (moderate: PHQ-9 scores of 10–14; moderately severe to severe: PHQ-9 scores of ≥ 15). A restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was performed to explore the dose-response relationship between CVH and all-cause mortality31. These statistical analyses were executed in R (version 4.3.0), using two-tailed tests, with a significance threshold set at P values < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of the 2,935 individuals diagnosed with depression (57.27% moderate, 42.73% moderately severe to severe) classified according to the level of CVH, with 38.40% of the participants having a low level of CVH, 56.01% of the participants having a moderate level of CVH and only 5.59% of the participants reaching a high level of CVH. Individuals with higher levels of CVH tended to be younger, female, have higher socioeconomic status (educational level and PIR), and lower PHQ-9 scores.

Over the course of a median follow-up period of 7.4 years (range: 4.1–10.7 years), 330 participants (11.24%) with depression were recorded to have died. Participants with depression at high CVH levels had significantly lower all-cause mortality than participants with depression at lower CVH levels (Fig. 2). Table 2 demonstrates the correlation between CVH and all-cause mortality among participants with depression. In model not adjusted for any covariates, each unit increase in CVH in participants with depression was associated with a 3% lower risk of all-cause mortality [HR = 0.97, 95%CI:0.96–0.98]. Moderate and high CVH levels were associated with a 48% [HR = 0.52, 95%CI:0.39–0.70] and 78% [HR = 0.22, 95%CI:0.08–0.65] lower risk of mortality risk, respectively, when compared to low CVH levels. This inverse association remained significant after adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic status variables. After adjusting for all covariates, each unit increase in CVH among participants with depression was correlated with a 3% lower mortality risk [HR = 0.97, 95%CI:0.96–0.98]. Participants with moderate levels of CVH and participants with high levels of CVH had a 37% [HR = 0.63, 95%CI:0.46–0.87] and 63% [HR = 0.37, 95%CI:0.11–1.10] lower mortality risk, respectively, compared to those with the bottom CVH group, although this inverse association was not statistically significant among participants with high levels of CVH, which was likely due to the small number of participants with high levels of CVH who recorded a death (n = 5), and the test for trend remained significant (P for trend < 0.001). Figure 3 shows that the total CVH score is linearly associated with all-cause mortality risk, with a nonlinearity P-value of 0.866, suggesting that as the total CVH score increased, the all-cause risk decreased linearly.

Kaplan–Meier Curves for All-Cause Mortality by CVH Level. CVH, Cardiovascular Health; LE8, Life’s Essential 8; HR, Hazard Ratio.CVH levels were defined as low (0 49), middle (50 79), and high (80 100) based on LE8 scoring. Eachcurve represents all cause mortality among participants categorized by CVH level.

Dose–Response Relationship Between Total LE8 Scores and All-Cause Mortality. CVH, Cardiovascular Health; PHQ 9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; CI, Confidence Interval. The solid line represents the estimated hazard ratio for all cause mortality with res tricted cubic splinemodeling, and the shaded region indicates the 95% CI. The model is adjusted for age, sex, race, education level,PIR, and PHQ 9 total scores.

To verify whether the association between CVH and all-cause mortality is robust in different populations with depression, subgroup analyses based on sex, age, education level, PIR and depression severity differences were investigated (Fig. 4). The results showed that the inverse association between CVH and all-cause mortality remained significant in all subgroups (all P for interaction > 0.05).

Subgroup Analyses of the Association Between CVH and All-Cause Mortality. HR, Hazard Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval; PIR, Ratio of Family Income to Poverty; CVH,Cardiovascular Health.Subgroups were defined by sex (male/female), age (<60/≥60), education (<high school, high school, >highschool), PIR (<1.3, school), PIR (<1.3, 1.31.3––3.0, >3.0) and depression severity (moderate/severe). Hazard ratios (95% CI) are from the 3.0, >3.0) and depression severity (moderate/severe). Hazard ratios (95% CI) are from the model adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, and PHQmodel adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, PIR, and PHQ--9 total scores. P9 total scores. P--values for interaction are shown values for interaction are shown on the right.on the right.

Discussion

In this prospective study involving 2,935 nationally representative participants with depression, we found an inverse association between CVH and all-cause mortality after adjusting for all covariates. Our findings suggest that maintaining optimal CVH may be associated with a lower mortality risk among individuals with depression. This provides prospective evidence supporting the importance of managing cardiovascular health to potentially extend life expectancy in this population. These results emphasize the need for an integrated healthcare approach that combines mental health management with cardiovascular disease prevention and intervention strategies.

Based on the NHANES sample of U.S. adults, three recent cross-sectional studies have investigated the association between CVH levels and the prevalence of depression in the general U.S. adult population20,21,32. The results of Shen et al. demonstrated a significant inverse non-linear association between CVH, as measured by the LE8 score, and depression, which remained stable across subgroups, with participants with high levels of CVH (80–100) serving as a reference, and participants with low levels of CVH (0–49) having an OR of 4.71 for depression prevalence20. Similar inverse associations were observed in the other two studies, although due to the differences in sample size and study methodology effect values21,32. However, these studies could not establish temporal relationships due to their cross-sectional design. Our results contribute prospective evidence on the association between higher levels of CVH and lower mortality in individuals with depression. This suggests that interventions aimed at improving CVH could have significant implications for reducing mortality in this group. From a clinical perspective, integrating CVH improvement strategies into mental health care could enhance overall health outcomes. For example, encouraging physical activity, healthy dietary habits, and smoking cessation not only benefits cardiovascular health but may also alleviate depressive symptoms33,34,35,36. Moreover, our findings have important public health implications. Given the high prevalence of depression and its substantial impact on morbidity and mortality, public health initiatives that promote CVH could play a crucial role in improving life expectancy and quality of life for individuals with depression. Future research should focus on developing and testing integrated intervention programs that address both mental health and cardiovascular risk factors.

Such an integrated approach has also been applied to populations with other chronic conditions. Studies have investigated the association between CVH and all-cause mortality in participants with diabetes and cancer, finding that higher CVH levels are linked with reduced mortality risk37,38,39. In addition, evidence from 341,331 participants in UK Biobank also suggests that high levels of CVH are linked with a lower risk of premature death and longer life expectancy40.

Importantly, integrating mental health and cardiovascular care may create a “virtuous cycle” wherein improvements in one domain facilitate gains in the other41,42. For instance, effective depression management can foster increased motivation for healthy behaviors—such as regular physical activity, balanced nutrition, and consistent medication adherence—that in turn enhance CVH. Meanwhile, better cardiovascular health may help stabilize mood and potentially reduce the physiological stress responses that exacerbate depressive symptoms17. Collaborative or stepped-care interventions focusing on both mental health and cardiovascular risk factors have demonstrated promising results, highlighting the potential synergy of combined treatment approaches43. Such interventions could not only lower the elevated mortality risk among individuals with depression but also improve their overall quality of life, underscoring the critical need for continued research and policy initiatives aimed at developing and disseminating integrated care models.

The level of CVH assessed by LE8 as a combined strategy (healthy behavioral lifestyle and biophenotyping) is what gives it its strengths over other metrics and is key to understanding the replication mechanism by which maintaining higher levels of CVH in individuals with depression reduces the risk of death. The quality of dietary intake, which is part of the assessment of CVH, has not only been linked to cardiovascular risk, but has also been shown to be an important factor in the management of stress and the maintenance of mental health44,45. Physical activity is closely related to brain structure and may activate brain function as well as improve cardiorespiratory fitness in depressed patients, thereby reducing cardiovascular risk46. Smoking, a traditional risk factor for cardiovascular disease, has also been suggested to increase susceptibility to depression and anxiety47. Alcohol abuse is also an important risk factor for cardiovascular and depression, and a multi-cohort study based in four European countries has shown that alcohol abuse is an important cause of reduced life expectancy in depressed patients48. Sleep disorders have long been recognized as a complication of depression, with several longitudinal studies demonstrating that sleep disorders are associated with higher cardiovascular risk as well as all-cause mortality49,50. Unhealthy biological phenotypes such as obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia are also important factors in depression and increased risk of death51,52,53,54.

Strengths of our study include the use of nationally representative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the association between CVH levels and all-cause mortality in individuals with depression. In addition, the LE8 score, as a comprehensive measure to evaluate CVH levels, provides a holistic view of cardiovascular health using multiple cardiovascular health indicators. We must also acknowledge some limitations of this study. First, the diagnosis of depression relies on self-report, which may introduce a potential participant selection bias. Another limitation is that we only investigated the association of CVH with all-cause mortality and not specific pre-existing deaths, due to the insufficient statistical size of 0 cardiovascular deaths among participants with high levels of CVH among approximately 3,000 participants with depression, which will need to be supplemented by larger prospective studies in the future. Finally, because CVH levels change over time, relying on a single measurement at baseline may not fully encapsulate the ongoing impact of CVH changes on health.

Conclusion

This study found that maintaining ideal CVH levels was associated with a lower risk of all-cause mortality among U.S. adults with depression. These findings suggest that managing CVH levels from the perspective of LE8 scores is important for maintaining health and prolonging life in individuals with depression. Larger prospective studies are essential to elucidate the association between CVH and different cause-specific deaths in populations with depression.

Data availability

NHANES data are publicly available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm. We intend to provide relevant code on written reasonable request.

Change history

21 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90554-7

Abbreviations

- AHA:

-

American Heart Association

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVH:

-

Cardiovasculardisease

- DASH:

-

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- LE8:

-

Life’s Essential 8

- LS7:

-

Lifes Simple 7

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- non-HDL:

-

Non high density lipoprotein

- PHQ 9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire9

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

References

Rotenstein, L. S. et al. Prevalence of Depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 316 (21), 2214–2236 (2016).

Monroe, S. M. & Harkness, K. L. Major Depression and its recurrences: Life course matters. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18, 329–357 (2022).

Alexopoulos, G. S. Depression in the elderly. Lancet 365 (9475), 1961–1970 (2005).

Laursen, T. M., Musliner, K. L., Benros, M. E., Vestergaard, M. & Munk-Olsen, T. Mortality and life expectancy in persons with severe unipolar depression. J. Affect. Disord. 193, 203–207 (2016).

Hare, D. L., Toukhsati, S. R., Johansson, P. & Jaarsma, T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review. Eur. Heart J. 35 (21), 1365–1372 (2014).

Mathew, A. R., Hogarth, L., Leventhal, A. M., Cook, J. W. & Hitsman, B. Cigarette smoking and depression comorbidity: Systematic review and proposed theoretical model. Addiction 112 (3), 401–412 (2017).

Marx, W. et al. Diet and depression: Exploring the biological mechanisms of action. Mol. Psychiatry. 26 (1), 134–150 (2021).

Ströhle, A. Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J. Neural Transm (Vienna). 116 (6), 777–784 (2009).

Boden, J. M. & Fergusson, D. M. Alcohol and depression. Addiction 106 (5), 906–914 (2011).

Zhang, Y., Chen, Y. & Ma, L. Depression and cardiovascular disease in elderly: Current understanding. J. Clin. Neurosci. 47, 1–5 (2018).

Lloyd-Jones, D. M. et al. Life’s essential 8: Updating and enhancing the American Heart Association’s construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 146 (5), e18–e43 (2022).

Ma, H. et al. Cardiovascular health and life expectancy among adults in the United States. Circulation 147 (15), 1137–1146 (2023).

Mahemuti, N. et al. Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio in normal range, Cardiovascular Health, and all-cause mortality. JAMA Netw. Open. 6 (12), e2348333 (2023).

Whooley, M. A. Depression and cardiovascular disease: Healing the broken-hearted. JAMA 295 (24), 2874–2881 (2006).

Katon, J. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 13 (1), 7–23 (2011).

Huffman, J. C., Celano, C. M. & Januzzi, J. L. The relationship between depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Neuropsychiatr Dis. Treat. 2010:123–136 .

Celano, C. M., Villegas, A. C., Albanese, A. M., Gaggin, H. K. & Huffman, J. C. Depression and anxiety in heart failure: A review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. 26 (4), 175–184 (2018).

Schulz, R. et al. Association between depression and mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 160 (12), 1761–1768 (2000).

Katon, W. J. et al. The association of comorbid depression with mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 28 (11), 2668–2672 (2005).

Shen, R. & Zou, T. The association between cardiovascular health and depression: Results from the 2007–2020 NHANES. Psychiatry Res. 331, 115663 (2024).

Zeng, G., Lin, Y., Lin, J., He, Y. & Wei, J. Association of cardiovascular health using Life’s essential 8 with depression: Findings from NHANES 2007–2018. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 87, 60–67 (2024).

Xie, R., Liu, X., Wu, H., Liu, M. & Zhang, Y. Associations between systemic immune-inflammation index and abdominal aortic calcification: Results of a nationwide survey. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 33 (7), 1437–1443 (2023).

Xie, R. & Zhang, Y. Associations between dietary flavonoid intake with hepatic steatosis and fibrosis quantified by VCTE: Evidence from NHANES and FNDDS. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 33 (6), 1179–1189 (2023).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (9), 606–613 (2001).

Manea, L., Gilbody, S. & McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ 184 (3), E191–196 (2012).

Sun, J. et al. Association of the American Heart Association’s new Life’s essential 8 with all-cause and cardiovascular disease-specific mortality: prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 21 (1), 116 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Relation of Life’s Essential 8 to the Genetic Predisposition for Cardiovascular Outcomes and All-cause Mortality: Results from a National Prospective Cohort. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. (2023).

Xie, R. et al. Associations of ethylene oxide exposure and Life’s Essential 8. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. Int. (2023).

Stekhoven, D. J. & Bühlmann, P. MissForest–non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 28 (1), 112–118 (2012).

Xie, R. et al. Novel type 2 diabetes prediction score based on traditional risk factors and circulating metabolites: Model derivation and validation in two large cohort studies. eClinicalMedicine 79. (2025).

Zhang, Y. et al. Associations between weight-adjusted waist index and bone mineral density: Results of a nationwide survey. BMC Endocr. Disord. 23 (1), 162 (2023).

Li, L. & Dai, F. Comparison of the associations between Life’s essential 8 and Life’s simple 7 with depression, as well as the mediating role of oxidative stress factors and inflammation: NHANES 2005–2018. J. Affect. Disord. 351, 31–39 (2024).

Rogerson, M. C., Murphy, B. M., Bird, S. & Morris, T. I don’t have the heart: A qualitative study of barriers to and facilitators of physical activity for people with coronary heart disease and depressive symptoms. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activity. 9, 1–9 (2012).

Marx, W. et al. Diet and depression: Future needs to unlock the potential. Mol. Psychiatry. 27 (2), 778–780 (2022).

Freedland, K. E., Carney, R. M. & Skala, J. A. Depression and smoking in coronary heart disease. Psychosom. Med. 67, S42–S46 (2005).

Zhang, Y., Liu, M. & Xie, R. Associations between cadmium exposure and whole-body aging: mediation analysis in the NHANES. BMC Public. Health. 23 (1), 1675 (2023).

Fan, C., Zhu, W., He, Y. & Da, M. The association between Life’s essential 8 and all-cause, cancer and non-cancer mortality in US Cancer survivors: A retrospective cohort study of NHANES. Prev. Med. 179, 107853 (2024).

Shen, R., Guo, X., Zou, T. & Ma, L. Associations of cardiovascular health assessed by life’s essential 8 with diabetic retinopathy and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Prim. Care Diabetes. 17 (5), 420–428 (2023).

Sun, Y. et al. Association between Life’s essential 8 score and risk of premature mortality in people with and without type 2 diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 39 (5), e3636 (2023).

Xu, C., Zhang, P. & Cao, Z. Cardiovascular health and healthy longevity in people with and without cardiometabolic disease: A prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 45, 101329 (2022).

Celano, C. M. & Huffman, J. C. Depression and cardiac disease: A review. Cardiol. Rev. 19 (3), 130–142 (2011).

Katon, W. J. et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl. J. Med. 363 (27), 2611–2620 (2010).

Davidson, K. W., Alcántara, C. & Miller, G. E. Selected psychological comorbidities in coronary heart disease: Challenges and grand opportunities. Am. Psychol. 73 (8), 1019 (2018).

Bremner, J. D. et al. Diet, stress and Mental Health. Nutrients 12(8). (2020).

Petersen, K. S. & Kris-Etherton, P. M. Diet Quality Assessment and the relationship between Diet Quality and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Nutrients 13(12). (2021).

Zhao, J. L. et al. Exercise, brain plasticity, and depression. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 26 (9), 885–895 (2020).

Fluharty, M., Taylor, A. E., Grabski, M. & Munafò, M. R. The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine Tob. Res. 19 (1), 3–13 (2017).

Moustgaard, H. et al. The contribution of alcohol-related deaths to the life-expectancy gap between people with and without depression - a cross-country comparison. Drug Alcohol Depend. 238, 109547 (2022).

Svensson, T. et al. Association of Sleep Duration with All- and major-cause mortality among adults in Japan, China, Singapore, and Korea. JAMA Netw. Open. 4 (9), e2122837 (2021).

Kwok, C. S. et al. Self-reported Sleep Duration and Quality and Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A dose-response Meta-analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7 (15), e008552 (2018).

Milaneschi, Y., Simmons, W. K., van Rossum, E. F. C. & Penninx, B. W. Depression and obesity: Evidence of shared biological mechanisms. Mol. Psychiatry. 24 (1), 18–33 (2019).

Brydges, C. R. et al. Metabolomic and inflammatory signatures of symptom dimensions in major depression. Brain Behav. Immun. 102, 42–52 (2022).

Scalco, A. Z., Scalco, M. Z., Azul, J. B. & Lotufo Neto, F. Hypertension and depression. Clin. (Sao Paulo). 60 (3), 241–250 (2005).

Semenkovich, K., Brown, M. E., Svrakic, D. M. & Lustman, P. J. Depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Drugs 75 (6), 577–587 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the United States CDC/NCHS for providing the NHANES 2005–2018 data.

Funding

This research was supported by Key Research Project of Science and Technology Department of Hunan Province (No. 2020SKC2009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing manuscript: Meili Li, Youwei Huang, and Yanyan Shen; data extraction and statistical analysis: Meili Li, Jie Zhou and Youwei Huang; reviewing and editing: Ruijie Xie, Xianzhou Lu, and Yanyan Shen. conceptualization, project administration, and supervision: Xianzhou Lu and Yanyan Shen. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

All human subjects involved in this study were treated in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Meili Li and Youwei Huang were omitted as equally contributing authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Huang, Y., Zhou, J. et al. The associations of cardiovascular health and all-cause mortality among individuals with depression. Sci Rep 15, 1370 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85870-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85870-x