Abstract

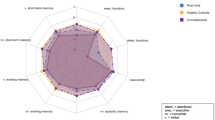

A substantial proportion of patients suffer from Post-COVID Syndrome (PCS) with fatigue and impairment of memory and concentration being the most important symptoms. We here set out to perform in-depth neuropsychological assessment of PCS patients referred to the Neurologic PCS clinic compared to patients without sequelae after COVID-19 (non-PCS) and healthy controls (HC) to decipher the most prevalent cognitive deficits. We included n = 60 PCS patients with neurologic symptoms, n = 15 non-PCS patients and n = 15 healthy controls. Basic socioeconomic data and subjective complaints were recorded. This was followed by a detailed neuropsychological test battery, including assessments of general orientation, motor and cognitive fatigue, screening of depressive and anxiety symptoms, information processing speed, concentration, visuomotor processing speed, attention, verbal short-term and working memory, cognitive flexibility, semantic and phonematic word fluency, as well as verbal and visual memory functions. Neurologic PCS patients had more complaints with significantly higher fatigue scores as well as higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms compared to Non-PCS and HC. Deep neuropsychological assessment showed that neurologic PCS patients performed worse in a general screening of cognitive deficits compared to HC. Neurologic PCS patients showed impaired mental flexibility as an executive subfunction, verbal short-term memory, working memory and general reactivity (prolonged reaction time). Multiple regression showed fatigue affected processing speed; depression did not. Self-reported cognitive deficits of patients with neurologic PCS including fatigue, concentration, and memory deficits, are well mirrored in impaired performance of cognitive domains of concentration and working memory. The present results should be considered to optimize treatment algorithms for therapy and rehabilitation programs of PCS patients with neurologic symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus type 2 (SARS-CoV-2) triggered one of the most severe pandemics in human history. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by the end of 2023, approximately 773 million people had contracted acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, resulting in the multi-organ coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19)1. Many of these affected patients continue to suffer from persistent or new symptoms, even 12 weeks after acute infection. This condition, in which symptoms persist or new symptoms develop at least three months after the acute infection and persist for at least two months without the finding of any causal relationship, is subsumed under the terms post COVID-19 condition2 or post-COVID syndrome (PCS)3. In the following, the term PCS refers to COVID-19 symptoms or new symptoms that cannot be attributed to any other etiology and persist more than 12 weeks after the acute COVID-19 infection. Symptoms commonly found and included in the symptom complex of PCS are hair loss, chronic kidney disease, thromboembolism, palpitations and chest pain, headache, cognitive impairment, post-traumatic stress disorder, sleep disturbances, anxiety and depressive symptoms, cough, shortness of breath, arthralgias, myalgias, and frequently and most importantly, chronic fatigue4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Neurological symptoms are particularly common, with fatigue and cognitive impairment being the most frequently documented5,6,10,11. Additionally, neurological and neuropsychiatric PCS encompasses symptoms such as dysosmia, sleep disorders, concentration deficits, amnesia, numbness, pain, depression, and anxiety12. The pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying PCS and its neurologic symptoms remain to be elucidated. However, regarding neuropathology, several competing mechanisms are hypothesized to explain this epiphenomenon. These include direct viral penetration, systemic inflammation with complement activation, microglia activation, activation of coagulation, oxidative stress, auto-immunity, and neurodegenerative processes13,14,15. From a clinical perspective, it is important to identify the most dominant cognitive deficits in these subjects and thus identify potential treatment targets for clinicians and basic researchers.

Therefore, the current study aims to perform in-depth neuropsychological assessment in patients with PCS to further elaborate on the neurological dimensions of PCS (for the sake of clarity and consistency, we will continue to use the abbreviation PCS throughout the text, tables, and graphs when referring to neurological PCS), subjects without clinical symptoms after COVID-19 (non-PCS) and healthy controls (HC).

Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from 1975 and was approved by the local ethics committee of Ruhr-University Bochum (20-6827; 21-7423). Patients and controls were recruited at our specialized neurological Long-COVID clinic (Department of Neurology, Ruhr-University Bochum, St. Josef-Hospital, Bochum, Germany). Patient inclusion began in January 2021. Written informed consent was mandatory for participation. Patients older than 18 years with a history of COVID-19 infection (a positive PCR result was not required) who met the criteria for post-COVID syndrome, as defined earlier, were included in the PCS group. The persisting symptoms prompting their presentation at our outpatient clinic primarily focused on, but were not limited to, neurological issues. Subjects with a history of COVID-19 infection but without evidence of PCS were included in the non-PCS group. Subjects without history of COVID-19 infection were recruited as healthy controls. After inclusion in the study, sociodemographic data were collected.

Self-assessment

Subjects completed a symptom self-assessment, including fatigue, muscle weakness, sleep disturbances, hair loss, olfactory disturbances, palpitations, joint pain, loss of appetite, taste disturbances, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, difficulty swallowing, skin rash, headache, muscle pain and memory disturbances. Additionally, subjects could report and specify other complaints or state that none of the mentioned symptoms were present. After completion of the self-assessment, neuropsychological testing was performed.

Neuropsychological test battery

Neuropsychological examinations were performed by or under the supervision of two experienced neuropsychologists. The test battery was composed of a total of 11 different psychometric tests covering the cognitive domains general orientation, motor and cognitive fatigue, screening of depressive and anxiety symptoms, information processing speed, concentration, visuomotor processing speed, attention (tonic and phasic alertness), verbal short-term and working memory, cognitive flexibility, semantic and phonematic word fluency, as well as verbal and visual memory functions (Supplementary methods).

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of the study was the number of subjects with PCS and substantial impairment of neurocognitive function as compared to non-PCS and HC. Data were presented as shown in the respective figure legends. Demographics, self-assessment, and clinical characteristics were compared. Depending on the psychometric procedure, raw scores, or standardized scores (z-scores) were calculated and used for analysis. Multiple regression analyses assessed the influence of group membership (PCS vs. non-PCS vs. HC), age, sex, education, and occupational status. FSMC total score, HADS-D, and HADS-A subscores were included as independent variables with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Results were initially analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. To adjust for multiple comparisons, the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY) was applied, with q < 0.05 considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 10.3.1).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 90 subjects were included in the study, with a female proportion of 65.5% (n = 59). The PCS group consisted of n = 60 individuals (female proportion of 71.6%, n = 43) with neurologic symptoms, and the non-PCS and HC groups consisted of n = 15 individuals each (female proportion of 53.3%, n = 8). The mean age of all patients was 44 years with a median of 46 years (Table 1 and Fig. S1a). There were no differences between the groups regarding age.

The maximum school qualification was classified using the CASMIN classification (Table 1 and Fig. S1). The mean qualification level was 7 (technical college graduation/ high school diploma and vocational training) with a median level of 7 (Table 1 and Fig. S1b), not differing between respective groups. The majority of all subjects had a lower secondary school leaving certificate and vocational training (35% PCS, 27% non-PCS, 33%HC), followed by subjects with a university degree (25% PCS, 53% non-PCS, 20%HC) and with a technical college graduation/ high school diploma and vocational training (18% PCS, 13% non-PCS, 7%HC). The remaining patients had a university of applied sciences degree, secondary school diploma and vocational training or advanced technical college certificate/ high school diploma without vocational training. Most subjects were employed (60% PCS, 80% non-PCS, 73%HC) (Table 1 and Fig. S1c).

Self-assessment of complaints

Symptoms were reported by 6.7% of subjects in the control group, specifically 12.5% of women (1 out of 8) and 0% of men. No symptoms were reported by the non-PCS group, whereas 100% of the Neurologic PCS group indicated they experienced complaints (Table 2). As part of the self-report questionnaire, subjects were asked to mark those symptoms which they were currently suffering from, based on a list of symptoms. While HC documented an average of n = 0.1 symptoms (median 0, range 0–2) and non-PCS group an average of n = 0 symptoms, subjects in the PCS group reported an average of n = 2 symptoms (median 2, range 1–4).

In the PCS group, 29 (48.3%) of the patients reported being exhausted, while this symptom was reported by none of the patients in the other groups. Most patients in the PCS group (n = 46 [77%]) reported suffering from memory impairment. Only one patient from the HC group and no patient from the non-PCS group reported this symptom. Lack of concentration was reported by 46 (76.7%) of the PCS patients and by one subject from the HC group. The least self-reported symptom was impairment of word-finding. From the PCS group this symptom was reported by n = 17 (28%) patients and none of the comparators.

Neuropsychological test battery

PCS patients suffer from significantly more motoric and cognitive fatigue compared to HC and non-PCS

Since a high proportion of patients reported being exhausted, we assessed exhaustion using the self-reported fatigue scale for motor and cognition (FSMC). The cut-off value for a pathological finding is ≥ 43 for the total score and ≥ 22 for the sub scores. While HC scored a mean of 16 points (median 15, range 10–31) and non-PCS 14 points (median 14, range 10–20) in the cognitive sub-scores, reflecting no cognitive fatigue, PCS patients were suffering from marked cognitive fatigue with an average of 39 points (median 41, range 16–50) which differed significantly from the control groups (PCS vs. HC and non-PCS total q < 0.0001; Fig. 1a). The motoric function documented similar results ((HC average: 15 points (median 13, range 10–28); non-PCS patients 14 points (median 13, range 10–25); PCS patients average 37 points (median 39, range 11–50)), hence significantly higher motoric fatigue in the PCS group compared to HC and non-PCS (Fig. 1b). The total scores reflected the findings of the sub-score analyses (Fig. 1c). A multiple regression identified significant predictors of increased exhaustion: belonging to the PCS group (β = 34.66, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.63) and depressive symptoms (HADS-D subscore) (β = 1.05, p = 0.02, R2 = 0.66) (Table 3). Neither sex nor age had a significant effect.

Cognitive and motor fatigue in PCS, non-PCS, and HC. (a) Cognitive fatigue, (b) motor fatigue, and (c) total fatigue are displayed, as assessed using the FSMC. Cut-off values for (a) cognitive fatigue are: minor fatigue = 22, moderate fatigue = 27, severe fatigue = 34. Cut-off values for (b) motor fatigue are: minor fatigue = 22, moderate fatigue = 27, severe fatigue = 32. (c) Cut-off values for total fatigue are: minor fatigue = 43, moderate fatigue = 53, severe fatigue = 63. Data is presented as individual values and as mean ± SD. Data were tested for significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons adjusted with the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY). The significance level was set at q < 0.05. PCS post-COVID syndrome, non-PCS non-post-COVID syndrome, HC healthy control, FSMC fatigue scale for motor and cognitive functions.

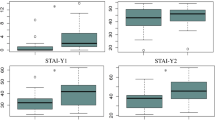

Increased levels of fatigue are associated with a greater prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms

To assess depressive and anxiety symptoms we used the German version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS-D). A total score of 8–10 is considered suspicious, a score > 10 is considered conspicuous. HC averaged 2 points (median 1, range 0–6), non-PCS patients 1 point (median 1, range 0–5) and PCS patients 8 points (mean 7, range 1–16), which was significantly higher compared to both HC and non-PCS (q < 0.0001) (Fig. 2a). In the anxiety sub score, PCS patients reached significantly higher scores with 9 points (mean 8, range 0–19) compared to HC (4 points (median 3, range 0–12), q = 0.0003) and non-PCS patients with 3 points (q < 0.0001; Fig. 2b). The regression analysis indicated that the FSMC total score was a significant predictor of both a higher HADS-D subscore (β = 0.12, p = 0.0007, R2 = 0.81) and HADS-A subscore (β = 0.1, p = 0.0077, R2 = 0.81) (Tables 4 and 5).

Depressive and anxiety symptoms in PCS, non-PCS and HC. (a) Shown is the depressive and (b) anxiety subscore, assessed using the HADS-D. Cut-off values are 0–7 = negative, 8–10 = indifferent, > 10 = positive. Data is shown as individual values including the mean +/- SD. Data were tested for significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons adjusted with the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY). The significance level was set at q < 0.05. PCS post-Covid syndrome, non-PCS non-Post-Covid syndrome, HC healthy control, SD standard deviation, HADS-D hospital anxiety and depression scale.

Assessment of cognitive functions shows fatiguability with impairment of processing speed

The general orientation was assessed using the WMS-R orientation questions. There were no relevant differences between the groups with an overall mean value of 14 (median 14, range 13–14) (not shown). A general screening for cognitive deficits was performed using the MoCa. On average, 27 raw score points were obtained in the PCS group (median 27, range 21–30), 28 in the non-PCS group (median 28, range 25–30), and 29 in the HC group (median 29, range 27–30). This was significant between PCS (total) and both control groups (PCS vs. HC: q = 0.0004; PCS vs. Non-PCS q = 0.0411; Fig. 3a). Regression analysis revealed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms, as indicated by the HADS-D subscore, was a significant predictor of reduced cognitive performance, measured by the MoCA score (β = -0.13, p = 0.05, R2 = 0.68) (Table 6).

General screening of cognitive deficits and processing speed and concentration in PCS, non-PCS and HC individuals. (a) The raw score achieved in the MoCa and (b) the result of the SDMT displayed as z-scores are shown. Data is shown as individual values including the mean +/- SD. Data were tested for significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons adjusted with the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY). The significance level was set at q < 0.05. PCS post-Covid syndrome, non-PCS non-post-Covid syndrome, HC healthy control, SD standard deviation, MoCa montreal cognitive assessment, SDMT symbol digit modalities test.

We assessed information processing speed and concentration using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT). A deviation of more than 1.5 standard deviations (SD) below the age norm is considered an indication of a disturbance. The non-PCS group achieved an average SD of 0.4 (median 0.3, range − 0.8 to 2) and HC achieved an SD of 0.3 (median 0.5, range − 2 to 2). The PCS-group scored a mean of -0.4 SD below the age norm (median − 0.3, range − 3 to 2), which was not statistically significant (Fig. 3b). The multiple regression analysis did not reveal any significantly influencing factor (Table 7). Since patients often complain about concentration and attention deficits, we set out to assess general alertness (tonic alertness) and specific responsiveness (phasic alertness) using the subtest Alertness of the Test for Attentional Performance (TAP) at two different time points. Examining tonic alertness during the first trial, HC achieved a SD of -0.7 (median − 0.8, range − 2.0 to 0.3), non-PCS patients a SD of -0.7 (median − 0.7, range − 2.0 to 0.2) and PCS-patients a SD of -1.0 (median − 1.0, range − 2.0 to 2.0) (ns; Fig. 4a). The second trial was conducted at the end of the test battery to potentially objectify fatiguability over time. HC achieved a SD of -0.3 (median − 0.2, range − 1.0 to 0.7), non-PCS patients achieved a SD of -0.6 (median − 0.6, range − 2.0 to 0.5) and PCS on average a SD of -1.0 (median − 2.0, range − 2.0 to 0.4), which was significantly slower comparing PCS vs. Non-PCS (q = 0.0017) (Fig. 4b).

Attentional performance in PCS, non-PCS and HC individuals. The attentional performance of the tested individuals is shown in the form of z-scores, tested using the TAP test at two time points (#1 in (a) and (c) and #2 in (b) and (d)) and in two subtests: tonic alertness shown in (a) and (b) and phasic alertness in (c) and (d). Data are displayed as individual z-scores with mean +/- SD. Data were tested for significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons adjusted with the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY). The significance level was set at q < 0.05. PCS post-Covid Syndrome, non-PCS non-post-Covid syndrome, HC healthy control, SD standard deviation, TAP test for attentional performance.

Examining the phasic alertness during the first trial HC scored on average a SD of -0.8 (median − 1, range − 2.0 to 0.9), non-PCS a SD of -0.5 (median − 0.5, range − 2.0 to 0.5), PCS − 0.03 (median − 0.3, range − 2.0 to 2.0). The difference between PCS and HC was significant with q = 0.0207 (Fig. 4c). This effect was unchanged during the second trial (HC mean SD -0.4 (median − 0.4, range − 1.0 to 0.5), non-PCS SD of -0.5 (median − 0.4, range − 1.0 to 0.6), PCS 0.2 (median 0, range − 1.0 to 0.4) (Fig. 4d). The multiple regression analysis did not reveal any significantly influencing factors (not shown).

Assessment of visuomotor processing speed, working memory and cognitive flexibility was conducted using the Trail Making Test versions A and B. In the TMT-A, HC achieved an SD of 0.3 (median 0.4, range − 0.9 to 1), non-PCS an average SD of 0.2 (median 0.1, range − 2 to 2) and PCS averagely a SD of -0.09 below the age norm (median − 0.1, range − 2 to 2). The TMT-B showed comparable results (HC SD of -0.2 (median − 0.1, range − 2 to 0.7); non-PCS average SD of -0.1 (median − 0.1, range − 2 to 2), PCS averagely a SD of -0.3 below the age norm (median − 0.4, range − 2 to 2) (ns; Fig. S2). The multiple regression analysis did not reveal an any significantly influencing factor (not shown).

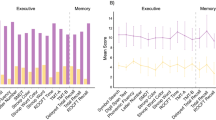

PCS patients have impaired verbal short-term and working memory as well as word fluency

PCS patients with neurologic symptoms often complain about impairment of word finding and word memory. We assessed verbal short-term and working memory using the digit span forward and backwards test from WMS-R. HC had a SD of 0.2 (median 0.4, range − 1.0 to 1.0), non-PCS achieved a SD of 1.0 (median 1.0, range − 0.7 to 2.0) and PCS-patients achieved on average a SD of -0.2 (median − 0.05, range − 2.0 to 3.0). This was significantly worse in the total PCS group (q < 0.0001) and HC (q = 0.0112) compared to non-PCS (Fig. 5a). In the backward digit span subtest PCS performed significantly worse than Non-PCS and HC (HC SD of 0.7 (median 0.4, range − 1.0 to 2.0); non-PCS SD of 0.6 (median 0.6, range − 1.0 to 2.0), PCS SD of -0.2 (median − 0.3 range − 2.0 to 3.0); PCS vs. HC q = 0.008 and PCS vs. Non-PCS q = 0.008)) (Fig. 5b). The regression analysis revealed that age was a significant predictor of a reduced performance regarding the backward subtest (β = -0.21, p = 0.015, R2 = 0.41) (Tables 8 and 9).

Verbal short-term and working memory in PCS, non-PCS and HC individuals. (a) Shown is the achieved z-score in digit span forward subtest and (b) digit span backward subtest using “Digit Span” test of the WMS-R. Three columns for each subgroup, divided into female (f), male (m) and total (total). Data are shown as individual values with mean +/- SD. Data were tested for significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons adjusted with the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY). The significance level was set at q < 0.05. PCS post-Covid syndrome, non-PCS non-Post-Covid syndrome, HC healthy control, SD standard deviation, WMS-R Wechsler memory test revised.

To assess cognitive flexibility, semantic and phonetic word fluency we used the Regensburger Word Fluency Test (RWT). Regarding word fluency, HC achieved a SD of 1.0 (median 1.0, range − 1.0 to 2.0), non-PCS a SD of 0.7 (median 0.7, range − 0.8 to 2.0) and PCS-patients achieved averagely a SD of -0.2 (median − 0.2, range − 2.0 to 2.0), which was significantly lower for PCS (total) compared to Non-PCS (q = 0.0059) (Fig. 6a). The regression analysis revealed that age was a significant predictor of an improved performance (β = 0.02, p = 0.02, R2 = 0.42) (Table 10). Results for phonetic category change showed significant differences between PCS and HC (q = 0.0302) (HC with SD of 0.6 (median 0.1, range − 0.7 to 2.0); non-PCS 0.3 (median 0.3, range − 2.0 to 2.0); PCS-patients − 0.2 (median 0.03, range − 2.0 to 1.0) (Fig. 6b). The multiple regression analysis did not reveal any significantly influencing factor (Table 11) In the investigation of semantic word fluency HC achieved a SD of 0.8 (median 1, range − 1.0 to 2.0), non-PCS patients achieved a SD of 0.9 (median 0.7, range − 0.6 to 2.0) and PCS-patients achieved on average a SD of 0.05 (median 0.1, range − 2.0 to 2.0) with a significant difference between PCS and Non-PCS (q = 0.0114) as well as PCS and HC (q = 0.0114) ( Fig. 6c). The regression analysis revealed that age was a significant predictor of an improved performance (β = 0.04, p = 0.0025, R2 = 0.41) (Table 12).

Cognitive flexibility and semantic and phonetic word fluency in PCS, non-PCS and HC individuals. (a) Shown are the z-scores in “phonetic word fluency” as well as in (b) the subtest “categories” and (c) subtest “semantic fluency” using the RWT. Data were tested for significance using the Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by multiple comparisons adjusted with the two-stage linear step-up procedure by Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli (BKY). The significance level was set at q < 0.05. PCS post-Covid syndrome, non-PCS non-Post-Covid syndrome, HC healthy control, SD standard deviation, RWT Regensburg Word Fluency Test.

Verbal memory function was investigated using the Verbal Learning and Memory Test (VLMT). The VLMT measures learning, consolidation, and recognition performance. Learning and consolidation did not significantly differ between groups (HC SD of -0.04 (median 0.7, range − 2.0 to 1.0); non-PCS 0.2 (median 0.7, range − 0.9 to 1.0); PCS 0.07 (median 0.2, range − 2.0 to 1.0); ns; Fig. S3a). Recognition performance was also not significantly different (HC achieved an SD of 0.5 (median 0.8, range − 1.0 to 2.0); non-PCS 0.6 (median 0.8, range − 0.5 to 2.0); PCS 0.3 (median 0.3, range − 2.0 to 2.0); ns, Fig. S3b). The overall performance conclusively did not significantly differ (HC SD of 0.8 (median 0.9, range − 0.8 to 2.0), non-PCS patients 1.0 (median 1.0, range 0.3 to 2.0); PCS-patients 0.3 (median 0.7, range − 2.0 to 2.0); ns, Fig. S3c). Regarding the overall performance the multiple regression analysis revealed that having a university degree was associated with better performance in VLMT (β = 0.62, p = 0.026, R2 = 0.44) (not shown).

Visual memory functions were investigated using the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test (BVMT-R). There was no significant difference between groups (HC SD of 0.8 (median 0.9, range − 0.8 to 2); non-PCS 1.0 (median 1.0, range 0.3 to 2.0); PCS 0.3 below the age norm (median 0.7, range − 2.0 to 2.0); Fig. S4). Regarding the subscore learning and consolidation multiple regression analysis revealed that exhaustion (FSMC total score) was a significant predictor of a reduced performance (β = -0.006, p = 0.04, R2 = 0.85) (not shown).

Discussion

Post-Covid is considered a potentially huge burden with massive implications for both the health care system and social economy. Impairment of cognition, in lay media summarized as “brain fog”, is often reported by patients. We here set out to decipher neuropsychological alterations of neurologic PCS patients with potential for a more streamlined therapeutic intervention.

Patients presenting at specialized outpatient clinics most commonly report fatigue, forgetfulness or brain fog11,16. This was also evident in neurologic PCS patients investigated in our cohort with significantly higher symptom burden compared to the control groups. Subjects with neurologic PCS felt more exhausted and suffered from memory and impairment of concentration. Moreover, PCS patients scored significantly higher in the HADS questionnaire assessing both depressive and anxiety symptoms. Using a machine learning approach, depressive symptoms as well as cognitive reserve, obesity and change in employment status predicted processing speed and executive function after COVID17. We found that PCS patients with neurologic symptoms were impaired in working memory and attention. Of note, we performed the TAP test twice during the neuropsychological assessment revealing significantly longer reaction times at the second investigation, potentially reflecting a consequence of cognitive fatiguability. In line with our findings, in two German and UK cohorts PCS patients showed pronounced cognitive slowing in 53.5% of patients with PCS. PCS response time was more than 2 standard deviations below the mean of the response time of the control group using a simple reaction time test18. Besides, neurologic PCS patients investigated here showed impairment of verbal short-term memory, cognitive flexibility and verbal fluency, often reported by patients with difficulties finding words.

Potential reasons for cognitive impairment are manifold. Combined neuropsychological assessment and MRI studies showed that patients with mild COVID with a median follow-up of 79 days after COVID had higher axial diffusivity values in diffusion tensor imaging, suggesting subtle white matter abnormalities after COVID19. This might be a consequence of immunological and vascular alterations induced by COVID. Recently, using RNA sequencing immunological alterations in PCS patients could be demonstrated. In a study of patients 12 months after COVID-19 multimodal proteomics analysis showed terminal complement system dysregulation and ongoing activation of the alternative and classical complement pathways20. This was associated with increased antibody titers against several herpesviruses. Hence, immune dysregulation with complement activation and thromboinflammatory protein activation might be a driver of PCS. This might also explain long-term cardiovascular outcome following COVID-19 with increased risk of cerebrovascular disorders, dysrhythmias, ischemic and non-ischemic heart disease, pericarditis, myocarditis, heart failure and thromboembolic disease21.

Using MRI, Besteher et al. demonstrated that there is a continuum of cortical thickness alterations, most pronounced in PCS patients with cognitive impairment assessed using the MOCA22. Additionally, multimodal neuroimaging revealed functional connectivity changes, including bihemispheric hypoconnectivity, reduced grey matter volume, and alterations in white matter. Importantly, grey matter loss was linked to cognitive impairment23. Of note, there were also elevated levels of IL-10, IFNγ, and sTREM2 in long-COVID patients, especially in the group suffering from cognitive impairment. Despite the rather small sample size investigated here, we found significantly lower performance in PCS patients compared to HC in the MOCA, a screening instrument for cognitive impairment. Whether long-term risk of cognitive impairment will be increased in PCS patients’ needs further investigation.

There are different therapeutic interventions under investigation. First, prevention is important using vaccination against SARS-CoV-2, since the risk of developing PCS is substantially reduced following vaccination as shown in a population-based study in Sweden with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.42 (95% confidence interval 0.38 to 0.46)24. Recently, the antidepressant vortioxetine showed positive effects in PCS patients in the Digit Symbol Substitution Test in those whose baseline C reactive protein (CRP) was above the mean25. Vortioxetine treated patients also showed significant improvement in measures of depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life, presumably due to the antidepressive effect. A post-hoc analysis documented that vortioxetine has positive effects on psychosocial functioning mediated by improvement of fatigue26. Since the cohort investigated here also showed higher levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms, positive effects on fatigue might rather be a consequence of the antidepressive effect. Besides, there are several other interventions currently under investigation such as a treatment with melatonin, which stimulates the expression of an intracellular antioxidant27, low-dose naltrexone, which may have immunomodulatory effects28 or hyperbaric oxygen therapy which is discussed to improve neurocognitive functions and symptoms by inducing neuroplasticity29. Further non-pharmacological interventions such as resistance exercises, Pilates, music therapy in combination with cognitive behavioural therapy, and neuromodulation using transcranial direct current stimulation have been explored for post-viral syndromes like PCS, but require more intensive investigation30.

Our study has limitations, including its single-center design and the relatively small sample size. Another key limitation is that most of the participants were recruited from our neurological post-COVID outpatient clinic, meaning they primarily had neurological or cognitive issues, making the study population highly selective. This limits the generalizability of our findings to broader groups of people with PCS. Furthermore, the lack of information regarding the comparability of different groups in terms of hospitalization and ICU admission, as well as premorbid comorbidities (particularly neuropsychiatric diagnoses), represents a significant limitation. A strength of the study herein lies in the high quality and broad neuropsychological test battery spanning different cognitive domains with the inclusion of age-matched subjects in the analysis herein.

In summary, our findings suggest that neurologic PCS patients may experience impairments in working memory and attention. However, we did not find evidence that fatigue was a significant influencing factor in the multiple regression analyses. Additionally, neurologic PCS patients tended to report increased symptoms of depression and anxiety, with a possible connection between depressive symptoms and fatigue. It remains unclear whether these issues are linked to a preexisting risk for affective disorders or are a result of the disability caused by the post-COVID condition. Our results may contribute to refining diagnostic procedures and therapeutic approaches for patients with suspected neurologic PCS. Future research should explore immunological and MRI changes alongside neuropsychological assessments to better understand potential diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for this patient group.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Number of COVID-19 cases reported to WHO. (cumulative total). https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (2023). (accessed January 14,2024).

Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). (2023). https://www.who.int/europe/newsroom/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition; (accessed October 23, 2023).

COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Dec 18 (2020).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 27 (4), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z (2021).

Ceban, F. et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in post-COVID-19 syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 101, 93–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.12.020 (2022).

van Kessel, S. A. M., Olde Hartman, T. C., Lucassen, P. L. B. J. & van Jaarsveld, C. H. M. Post-acute and long-COVID-19 symptoms in patients with mild diseases: a systematic review. Fam. Pract. 39 (1), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmab076 (2022).

Sykes, D. L. et al. Post-COVID-19 Symptom Burden: what is Long-COVID and how should we manage it? Lung 199 (2), 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-021-00423-z (2021).

Global Burden of Disease Long COVID Collaborators et al. Estimated global proportions of individuals with persistent fatigue, cognitive, and respiratory symptom clusters following symptomatic COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021. JAMA 328 (16), 1604–1615. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.18931 (2022).

Raveendran, A. V., Jayadevan, R., Sashidharan, S. & Long, C. O. V. I. D. An overview, Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 15(3), 869–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.007 (2021).

Calabria, M. et al. Post-COVID-19 fatigue: the contribution of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms. J. Neurol. 269 (8), 3990–3999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-022-11141-8 (2022).

Schulze, H. et al. Cross-sectional analysis of clinical aspects in patients with long-COVID and post-COVID syndrome. Front. Neurol. 13, 979152. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.979152 (2022).

Takao, M. & Ohira, M. Neurological post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 77 (2), 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13481 (2023).

Nalbandian, A. et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat. Med. 27, 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01283-z (2021).

Castanares-Zapatero, D. et al. Pathophysiology and mechanism of long COVID: a comprehensive review. Ann. Med. 54 (1), 1473–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2022.2076901 (2022).

Seibert, F. S. et al. Severity of neurological Long-COVID symptoms correlates with increased level of autoantibodies targeting vasoregulatory and autonomic nervous system receptors. Autoimmune Rev. 22 (11), 103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2023 (2023).

Aziz, R. et al. Clinical characteristics of long COVID patients presenting to a dedicated academic post-COVID-19 clinic in Central Texas. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 21971. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48502-w (2023).

Ariza, M. et al. Cognitive reserve, depressive symptoms, obesity, and change in employment status predict mental processing speed and executive function after COVID-19. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-023-01748-x (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Long COVID is associated with severe cognitive slowing: a multicentre cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine 68, 102434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102434 (2024).

Scardua-Silva, L. et al. Duarte de Sousa JG, Marchiori de Oliveira Cardoso TA, Schwambach Vieira A, Barbosa Santos LM, Dos Santos Farias C. Microstructural brain abnormalities, fatigue, and cognitive dysfunction after mild COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52005-7 (2024).

Cervia-Hasler, C. et al. Persistent complement dysregulation with signs of thromboinflammation in active long covid. Science 383 (6680), eadg7942. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adg7942 (2024).

Xie, Y. et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 28, 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3 (2022).

Besteher, B. et al. Cortical thickness alterations and systemic inflammation define long-COVID patients with cognitive impairment. Brain Behav. Immun. 116, 175–184 (2024).

Díez-Cirarda, M. et al. Multimodal neuroimaging in post-COVID syndrome and correlation with cognition. Brain 146 (5), 2142–2152. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac384 (2023).

Lundberg-Morris, L. et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against post-covid-19 condition among 589 722 individuals in Sweden: population based cohort study. BMJ 383, e076990. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-076990 (2023).

McIntyre, R. S. et al. Vortioxetine for the treatment of post-COVID-19 condition: a randomized controlled trial. Brain 4, awad377. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awad377 (2023).

Badulescu, S. et al. Impact of vortioxetine on psychosocial functioning moderated by symptoms of fatigue in post-COVID-19 condition: a secondary analysis. Neurol. Sci.. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-024-07377-z (2024).

Jarrott, B., Head, R., Pringle, K. G., Lumbers, E. R. & Martin, J. H. LONG COVID-A hypothesis for understanding the biological basis and pharmacological treatment strategy. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 10 (1), e00911. https://doi.org/10.1002/prp2.911 (2022).

O’Kelly, B. et al. Safety and efficacy of low dose naltrexone in a long covid cohort; an interventional pre-post study. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 24, 100485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbih.2022.100485 (2022).

Zilberman-Itskovich, S. et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves neurocognitive functions and symptoms of post-COVID condition: randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 11252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-15565-0 (2022).

Chandan, J. S. et al. TLC study. Non-pharmacological therapies for post-viral syndromes, including long COVID: a systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 20 (4), 3477. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043477 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients for allowing them to analyze their data and participate in the study. We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr-University Bochum.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JCJ, HS: writing the manuscript, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data. NS, CP, DRQ, NT: revising the manuscript and acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data. RG: revising the manuscript, analysis, and interpretation of data. SF: writing the manuscript, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of data, study concept and design, and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Ruhr-University Bochum (20-6827 and 21-7423). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Charles James, J., Schulze, H., Siems, N. et al. Neurological post-COVID syndrome is associated with substantial impairment of verbal short-term and working memory. Sci Rep 15, 1695 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85919-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85919-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Excess primary healthcare consultations in Norway in 2024 compared to pre-COVID-19-pandemic baseline trends

Archives of Public Health (2026)