Abstract

It is well established that maternal factors can affect the abilities of offspring to cope with stressors and can influence their overall welfare states. However, maternal effects have not been extensively explored in US commercial breeding kennels (CBKs). Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify if fear and stress in dams affected puppy welfare metrics in CBKs. Bitches (n = 90) were tested at 6 weeks prepartum (6 W Pre), and again with their puppies (n = 390) at 4 (4 W Post) and 8 weeks (8 W Post) postpartum. Dams and puppies underwent stranger approach and isolation tests, and their feces were collected to measure fecal glucocorticoid metabolite (FGM) and secretory immunoglobulin A concentrations. Further, dams’ hair cortisol concentrations (HCC) were analyzed at the previously mentioned time points and at 1 week prepartum. Finally, birth and weekly weights were collected from puppies, and litter health metrics were recorded. Data were analyzed using mixed-effects and simple linear regression models. There were significant positive associations between dams’ exploration and stationary durations and puppies’ durations of the same respective behaviors during the isolation tests (exploration: \(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 9.472, p = 0.002; stationary: \(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 5.226, p = 0.022), 8 W Post dam FGMs and 8 W Post puppy FGMs (estimate: 0.0003, SE = 0.0001, p = 0.002), and 4 W Post dam HCCs and 4 W Post litter FGMs (estimate: 0.052, SE = 0.025, p = 0.053). Significant negative associations between 6 W Pre dam HCCs and 8 W Post puppy FGMs (estimate: -0.021, SE = 0.007, p = 0.007), puppies’ birth weights (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 3.908, p = 0.048), and puppies’ average weekly weight gains (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.111, p = 0.739) were also found. These findings suggest that indicators of dam fear and stress may be associated with potential indicators of puppies’ welfare states in CBKs. Findings provide new knowledge on fear and stress-related factors that may be used to support the welfare of dams and puppies in CBKs and other populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Some of the earliest studies on dog behavior have reported significant maternal effects on puppies’ behaviors in response to stressors1,2,3. However, these effects have not been explored in US commercial breeding kennels (CBKs). A recent study in this population found that puppies’ responses to stressors varied, with some differences being observed at the litter level, suggesting possible effects of their dams4. Exploring these effects more extensively in CBKs may provide important insight into the factors that might influence puppies’ stress susceptibilities and inform efforts to understand and support their abilities to cope when confronted with inevitable stressors.

Studies suggest that mothers may influence the stress responses and overall welfare of their offspring via genetic mechanisms, prenatal stress, maternal care, and social learning. For example, Wilsson and Sundgren1 found that puppies’ behavioral responses to various tests, some of which elicited a fear response, were associated with the genetics of their dams. In dogs from CBKs specifically, heritability estimates for responses to stranger approach ranged from 0.09 to 0.345, though the strength of genetic influence from sires vs. dams is still unknown.

In addition to heritable factors, studies in other species illustrate that prenatal stress experienced by the dam may be associated with litter-related outcomes such as reduced birthweights and female-biased sex ratios, and may affect how her offspring respond to stressful scenarios6. For example, an experiment conducted in blue foxes, a species closely related to domestic dogs, found that offspring of prenatally stressed vixens exhibited more behavioral reactivity than those of vixens who were not prenatally stressed7. This was evidenced by aggression and increased escape attempts in an open-field test7. The authors also reported that serum progesterone concentrations, which are associated with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation alongside glucocorticoids8, were higher, adrenal weights were lower, and, in females only, in-vitro adrenal production of glucocorticoids was higher in offspring of prenatally stressed vixens than those of vixens who were not prenatally stressed7. These findings are supported by studies in other species, which cite behavioral abnormalities and hyperactive HPA axes in offspring of prenatally stressed mothers6,9.

Furthermore, the quantity and quality of maternal care provided to offspring can significantly impact how they respond to future stressors. In rodents, increased quantities of licking, grooming, and arched-back nursing (ABN) have been associated with decreased behavioral and physiological indicators of fear and stress and increased spatial learning and memory in offspring10,11,12,13. In dogs, increased quantities of maternal care have been associated with both positive and negative outcomes for puppies, such as increased or decreased behavioral and physiological signs of fear and stress, increased social and physical engagement and aggression, and decreased problem solving14,15,16,17,18. Differences between studies may be due to factors such as breed, environment, and management practices. Further, it is important to note that prenatal stress and fear may be some of the many factors that affect the quantity and quality of dams’ maternal behaviors12,19,20,21,22.

Finally, puppies’ responses to stressors may be shaped by social learning facilitated by their dams. Slabbert and Rasa23 found that puppies who observed their dams retrieve a hidden object multiple times during early life were more successful at completing the task themselves at 6 months old, compared to those who did not receive these prior observational experiences. In contrast, Fugazza et al.24 reported that the probabilities of 8-week-old puppies’ problem-solving did not differ between those who previously observed their dam performing a problem-solving task and a control group. However, their findings conflict with those conducted with other species, which discovered that social learning facilitated by mothers is present early in life (e.g., kittens25 and wild orangutans26) and can result in in offspring learning to be fearful of certain stimuli (e.g., humans27, rhesus monkeys28). Therefore, although there are few published studies that have examined these effects with puppies, it is plausible that puppies may observe their dams’ behavioral responses early in life and subsequently respond similarly.

Altogether, the existing findings suggest that maternal fear and stress may profoundly affect offspring ability to cope with future stressors, which in turn, may influence their overall welfare. Exploring how maternal fear and stress influences puppy welfare may have important implications for breeding bitch selection in CBKs, with the aim to maximize puppies’ abilities to cope with future stressors. Most puppies from CBKs are transported to a distributor for sale, and some may be sold directly to customers or kept as breeding stock and potentially rehomed after their careers have ended. Throughout these processes they are likely to experience interactions with new people, separation from their dams, littermates, and/or conspecifics, and novel environments and management practices.

Different tests exist that may facilitate understanding of how puppies may respond to these real-life stressors. For example, stranger approach tests have been conducted with dams and puppies from CBKs4,29, and may provide insight into how they might respond to an unfamiliar person outside of the kennel. A variety of responses ranging from affiliation to avoidance have been observed in previous studies4,29. Isolation tests have also been conducted with puppies from CBKs4,29, and may elucidate how they might respond to scenarios such as separation from their littermates. Puppies from CBKs have demonstrated varying durations of exploration, locomotion, and attempting to escape, and frequencies of vocalizations during such tests, which may also help to gauge their overall levels of distress under these circumstances4,29. In addition to measuring puppies’ behavioral responses, certain physiological metrics may provide information as to how they respond to stressors. For example, as previously mentioned, glucocorticoids are associated with HPA activation and are indicative of arousal and, potentially, distress30,31,32. In addition, an individual’s immune function can change in response to stress and may be a useful metric when evaluating responses to stressors, and overall welfare31,33. Shorter-term, more invasive indices of these physiological metrics (i.e., saliva, plasma) are difficult to collect in CBKs, as the handling necessary to obtain samples can affect concentrations34,35. Less invasive indices of glucocorticoids and immune function, such as fecal glucocorticoid metabolites (FGM), fecal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA), and hair cortisol concentrations (HCC), may be more feasible. FGM and fecal sIgA capture HPA activation over a longer-term as compared to salivary metrics36,37, but indicate stress experienced over a shorter timeframe as compared to HCCs, which reflect HPA activation over weeks to months34. These metrics have previously been collected in dams and puppies from CBKs4,38,39,40. Finally, physical health and litter health metrics may be indicative of dam stress and puppy welfare, as an important aspect of animal welfare is basic biological health and functioning41. In CBKs, dams’ physical health has previously been evaluated using a visual physical health assessment39,42, and a novel adaptation of this tool has recently been developed to assess that of their puppies4,29.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to examine the effects of fear and stress in dams on puppy welfare outcomes. We hypothesized that dams who scored high on behavioral measures of fear and physiological measures of stress would have puppies who scored similarly on equivalent measures. Furthermore, we hypothesized that litter health metrics would be associated with measures reflective of their respective dams’ HPA activation during gestation.

Materials and methods

Ethics Statement

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Experimental procedures and sample sizes were approved by Purdue University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 1809001797, date of approval 11/13/2018). Breeders were required to sign a consent form before commencement of the study to enroll dams and puppies from their kennels. Breeders’ participation in the study was voluntary, and they were permitted to withdraw at any point for any reason. Although it did not occur in the current study, our protocol was to immediately stop testing if dams or puppies showed signs of extreme fear and/or aggression (e.g., repeated bouts of lunging, growling, escape attempts) that caused concern for the experimenter’s and/or dog’s safety. Further, if the experimenters or the breeder identified significant health issues in dams or puppies (e.g., vomiting, severe upper respiratory issues, injury) they were excluded from the study at that time point.

Subjects

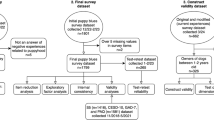

Twelve CBKs in the Midwestern United States (Indiana, Ohio, Missouri) were enrolled in the current study. Multiple kennels were included to account for differences in environment and management practices. All kennels were licensed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)43, and met or exceeded all federal and state regulatory requirements. Subjects enrolled in the study were 126 dams (mean age = 3.02 years old, s.d.= 1.24, range = 1–6 years old) representing 26 breeds or crossbreeds, and their litters (412 puppies; 205 males, 207 females) which included 31 breeds or crossbreeds (Supplementary Table S1). A minimum of seven and a maximum of 16 dams were tested at each kennel to capture variation within kennels (e.g., breed, maternal factors), and account for data loss due to failed conception, time constraints, etc. A total of 34 dams and 22 puppies were excluded from the final analyses for reasons such as failure to conceive, cross-fostering of puppies, delivering only a single stillborn puppy, or requiring a cesarean section/being a puppy born via cesarean section. Any animals who died during the study period were also removed from analysis (dams: n = 1, puppies: n = 8, deaths were unrelated to study procedures). Further, to minimize the effects of developmental differences between litters, 15 dams and their litters (n = 65 puppies) were excluded from the 4 W Post time point final analyses as puppies were less than 4 weeks old when testing occurred. Therefore, the final analyses included data from 90 dams with a mean age of 2.94 years old (s.d.= 1.19 years old, range = 1–6 years old) which included 24 breeds or crossbreeds, and 390 puppies (198 males, 192 females) representing 31 breeds or crossbreeds (Supplementary Table S1).

All puppies were housed with their dams until weaning (around 6–7 weeks of age) and with littermates until approximately 8 weeks of age when they were transported to a distributor on a predetermined day of the week. Three facilities reported providing socialization to their puppies daily, five reported providing socialization to their puppies at least twice a week, one reported never or rarely providing socialization their puppies, and there were no responses regarding puppy socialization for two facilities. Dams were group-housed (typically with others of the same size and compatible temperaments as determined by breeders) until approximately 1 week pre-partum when they were moved to individual whelping pens. All whelping pens were partitioned into two areas with a small barrier that contained puppies in one of the areas, while allowing the dams to move away from the litter to the adjacent area. Dams were not in physical contact with other dams and their litters while housed in whelping pens, but the potential for olfactory and visual contact existed and varied depending on their location in the kennel. Pens varied in size to accommodate dogs of different sizes and had various flooring types (e.g., diamond-shaped coated expanded metal, tile). Dams were provided with continuous access to a commercially available dry diet and water.

Experimental Procedure

Data collection occurred from June 2019 to December 2021. To ensure biosecurity, experimenters put on new disposable boot covers (Innovative Haus, Premium Thick Waterproof Disposable Shoe Covers) and nitrile gloves (KIMTECH™) before entry into each kennel. Gloves were changed between testing of each litter. Dams were tested at approximately 6 weeks prepartum (6 W Pre), and again at 4 and 8 weeks postpartum (4 W Post and 8 W Post) with their litters. The 6 W Pre timepoint was intended to act as a baseline measure for dams, as it preceded the period of highest biological and psychological stress associated with hormonal changes occurring during the peri-parturient period as well as adjustments to the dams’ social and physical environments, and related breeder management practices38. At each time point (only 4 W Post and 8 W Post for puppies), dams and puppies were subjected to a three-step stranger approach test, visual physical health assessment, and fecal collection for FGM, and fecal sIgA concentrations. Hair for HCC was also collected from dams at each time point, and at 1 week prepartum, but could not be collected from puppies as they were being transported to a distributor and sold after testing at 8 W Post. The stranger approach test was conducted and scored live by one of three equally trained, female experimenters. A research assistant stood off to the side and recorded the experimenter’s scores into a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) on an iPad (Apple Inc.). In most cases, individual dams and puppies were tested by the same experimenter at each time point. Additionally, at 8 W Post, dams and puppies underwent a one-minute isolation test. Finally, while puppies were still at the breeder, litter health metrics and individual puppies’ weights were collected weekly from birth to 8 W Post by the breeder or a caretaker.

Dam isolation test

At 8 W Post, prior to all other testing, experimenters constructed a large arena to conduct the dam isolation test. Depending on the weather and space constraints within the kennel, the arena was either placed in a large area within the facility or outside on the CBK property. The flooring consisted of 25 black interlocking rubber tiles (Armor-Lock Black Interlocking Rubber Tiles, 0.50 m by 0.50 m, Rubber-Cal Inc., Fountain Valley, CA, USA). Two metal exercise pens connected to each other (MidWest Foldable Metal Exercise Pen, Black w/ door, MidWest Homes For Pets, Muncie, IN, USA) were placed around the perimeter of the tiles. Each side was approximately 4.88 m long, and 1.22 m tall. To provide a visual barrier and reduce environmental distraction during testing, the sides of the pen were affixed with thick, black plastic sheets using zip ties. Small pieces of PVC pipe were attached to the inside of each corner with yarn to aid in stability. A small camera (GoPro Hero 5, GoPro Inc., San Mateo, CA, USA) was attached to the top of one side of the pen using a flexible camera mount to record testing. The camera was angled to ensure that all activity in the pen could be captured. A visual representation of the test can be seen in Fig. 1a.

Dams underwent the isolation test after the stranger approach test and before physiological metric collection. Selection for testing occurred in no specific order. Once the arena was assembled, familiar caretakers transported dams individually from their home pens to the arena. Dams had no exposure to this arena prior to testing. Caretakers placed the dam in the center of the arena, stepped outside, closed the door, and stood outside of the dam’s sightline. The experimenter, who was also standing outside of the arena and out of the dam’s sightline, waited for one minute (measured by a stopwatch or cellphone timer) until instructing the caretaker to retrieve the dam.

Dams’ behaviors during the isolation test were continuously recorded using the ethogram described in Table 1. The behavioral recording software, BORIS44, was used to facilitate such coding. Two experimenters coded all videos.

Puppy isolation test

At 8 W Post, the puppy isolation test was performed and scored as outlined in Romaniuk et al.4. Puppies within litters were tested in no particular order and litters were tested one after another. At the beginning of testing, each puppy was removed from their pen and placed in the center of a small arena by a familiar caretaker. The arena was an exercise pen configured into a hexagon with six 0.76 m tall black wire panels (Precision Pet Products, Costa Mesa, CA, USA) on top of six black interlocking rubber tiles (Armor-Lock Black Interlocking Rubber Tiles, 0.50 m by 0.50 m, Rubber-Cal Inc., Fountain Valley, CA, USA). The pen did not have a visual barrier comparable to the dam isolation test as puppies do not have fully developed visual acuity at this age, which limited their visual acuity of the area outside of the pen. A portable camcorder (Handycam HDR-CX405, SONY, Tokyo, Japan) on top of a tripod was placed outside of the arena to record the puppies’ behaviors during the test. A visual representation of the test can be seen in Fig. 1b. Once an individual puppy was placed in the middle of the arena, the experimenter moved a few steps backward and started a one-minute timer (stopwatch or cellphone timer). Throughout the test, experimenters, and anyone else in the testing room were quiet and did not visually interact with the puppy in the isolation pen. Puppies had previously experienced this test at 4 W Post (not included in the current study).

Puppies’ behaviors during the isolation test were continuously scored from video using the ethogram described in Table 1. The behavioral coding software, BORIS44, was utilized to do so. At each time point, videos were coded by two different experimenters.

Dam Stranger Approach Test

Dams were individually confined to the interior portions of their home pens at each time point before undergoing any other behavioral testing or physiological metric collection. They were given three minutes to habituate and then tested using a version of the behavioral section of the Field Instantaneous Dog Observation Tool (FIDO+)39,42,51. At 6 W Pre, the test was recorded using a tripod and portable camcorder (Handycam HDR-CX405, SONY, Tokyo, Japan) for reliability analyses. The test consisted of three steps, as outlined by Stella et al.39 and Barnard et al.51. The steps were conducted as follows: Approach (step 1)—the unfamiliar experimenter approached the pen with a sideways orientation, knees bent, and an averted gaze, and scored the immediate behavioral response of the dam, then tossed a treat (1 cm pieces of Canine Carry Outs or Pup-Peroni, Big Heart Pet, Inc., Walnut Creek, CA, USA) over/ through the front bars of the pen and recorded whether or not the dam ate it; Open (step 2)—the unfamiliar experimenter, with the same orientation, body posture, and gaze, opened the door to the pen and scored the immediate behavioral response of the dam, then extended one of their hands to offer the dam a treat and recorded whether or not they ate it; Reach (step 3)—the unfamiliar experimenter, with the same orientation, body posture, and gaze, simultaneously extended one hand toward the dam to offer them a treat and the other to attempt to touch the dam’s shoulder or chest, then recorded if the dam ate the treat and they could touch the dam. Touch was scored as ‘no’ if the dam was in reach but showed signs of fear, or avoidance. Dams’ immediate behavioral responses were scored as either red, yellow, or green, as originally outlined by Bauer et al.42. A red response indicated fearful behavior (e.g., calming signals, avoidance, freezing, aggression), a yellow response indicated ambivalence (e.g., approaching and avoiding the experimenter), and a green response indicated affiliative or neutral behavior (e.g., approaching the experimenter with relaxed body language, eating, drinking).

Puppy Stranger Approach Test

While puppies were still in the isolation pen, immediately after the isolation test, they underwent a three-step stranger test that has been previously described by Romaniuk et al.4 and Boone et al.29. All tests were recorded with a tripod and a portable camcorder (Handycam HDR-CX405, SONY, Tokyo, Japan). The stranger approach test consisted of three steps as follows: Approach (step one)— the unfamiliar experimenter crouched down in front of the pen with a sideways orientation and averted gaze, scored the immediate behavioral response of the puppy, then tossed a treat (small pieces of Canine Carry Outs or Pup-Peroni, Big Heart Pet, Inc., Walnut Creek, CA, USA) to the puppy through the bars of the pen and recorded whether they ate it or not; Open (step two)— the unfamiliar experimenter, with the same body position, orientation, and gaze, opened the door to the pen, scored the immediate behavioral response of the puppy, then extended one hand toward the puppy to offer them a treat and recorded whether or not they ate it; Reach (step three)—with the same orientation and gaze, the experimenter simultaneously extended one hand toward the puppy to offer them a treat, and the other to attempt to touch the puppy, then recorded whether or not the puppy ate the treat and they could touch the puppy. Touch was scored as ‘no’ if the puppy was in reach but showed signs of fear or avoidance. As puppies may have had limited visual acuity and mobility, but fully developed auditory startle responses at both time points52,53, they were often prompted with soft kissing noises and tapping on the pen to ensure they were aware of the experimenter’s presence. They were also scored as eating the treat if they attempted to do so but did not completely ingest it.

Puppies’ behavioral responses to the test were scored from video by one coder (AR) using a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) and the ethogram detailed in Table 2. For each step, each puppy was given a score for the orientation, response, and posture categories, and, if applicable, they were also given scores for modifier and additional categories.

Dam physical health assessment

The visual physical health assessments for dams were completed after behavioral testing. The assessment was originally outlined by Bauer et al.42 and Stella et al.39 and had a high agreement with hands-on physical health exams in CBKs39. The assessment was scored as follows: body condition score (BCS) on a sale of 1–5 (1 = emaciated, 2 = thin, 3 = moderate, 4 = stout, 5 = obese), body cleanliness as indicated by percentage of the body covered in debris (0%, \(\:\le\:\)25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, \(\:\ge\:\)76%), tear staining (none, mild, moderate, severe), and presence or absence of nasal and/or ocular discharge, sneezing, coughing, wounds, sores or lesions, missing fur or poor coat, and lameness.

Puppy physical health assessment

The visual health assessments for puppies were conducted immediately after the stranger approach test, as outlined by Romaniuk et al.4: body condition score (BCS) on a scale of 1–3 (1 = thin, 2 = normal, 3 = obese), cleanliness indicated by the percentage of the puppies’ bodies covered in debris (0%, \(\:\le\:\)25%, 26–50%, 51–75%, \(\:\ge\:\)76%), severity of tear staining (none, mild, moderate, severe), and presence or absence of nasal and/or ocular discharge, diarrhea, symptoms of upper respiratory infection (URI), sneezing, coughing, poor coat condition, wounds, and/or pyoderma (skin infection).

Litter health metrics and puppy weights

At whelping, breeders noted litter sizes, the number of puppies born alive, and the number of males and females in each litter. Furthermore, individual puppies’ birth and weekly weights were collected by breeders or caretakers until they were transported to a distributor at approximately 8 weeks old.

HCC

Hair collection occurred at every time point (i.e., shave re-shave technique), and additionally at 1 week prepartum. Thus, the 4 W Post sample was representative of the time from just before whelping to 4 weeks postpartum. Further, Romaniuk et al.38 found that dams’ HCCs in CBKs at 6 and 1 week prepartum were not significantly different, which suggests that long-term baseline HPA activation in dams may be similar to that occurring throughout gestation. Although Romaniuk et al.’s38 sample was a subset of subjects from the current study, we performed additional analyses to determine if the similarity in HCCs between 6 and 1 week prepartum held in the current study. Means and standard deviations were calculated and showed that, on average, dams’ HCCs at 6 and 1 week prepartum were almost identical (6 W Pre: n = 82, mean = 20.42 pg/mg, s.d.=12.08; 1 W: n = 64, mean = 20.44 pg/mg, s.d.= 10.38). Therefore, dams’ HCCs at 1 week prepartum were not further evaluated in the current study.

To ensure low-stress handling, hair collection occurred in the same location in which dams commonly underwent medical and/or grooming procedures (e.g., in their pen, a separate room of the kennel). Throughout collection, dams were presented with baby food (Turkey, Ham, or Chicken and Gravy; Gerber, Nestle, Florham Park, NJ, USA) on a disposable plate, spatula, or tongue depressor. A familiar caretaker placed the dam on a non-slip surface (one was provided by experimenters if it was not available in the kennel), and their lower lumbar area (base of tail) was shaved using electric clippers (Arco Pet Cordless Clipper, Wahl Professional, Sterling, IL, USA) to collect approximately 50 mg of hair. Hair samples were placed in small manila envelopes sealed with tape and stored in a cool, dry area. To avoid contamination of samples, clippers were cleaned with compressed air and alcohol wipes between collection from different dams.

Hair samples were shipped for analyses in four batches. Cortisol levels in hair samples were determined by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Salimetrics, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in the Endocrine Technologies Core (ETSC) at the Oregon National Primate Research Center (ONPRC) using a modification of an existing protocol55. This protocol was identical to that described by Stella et al.39 and Romaniuk et al.38. Hair samples were washed with isopropanol, drained through P8 filter paper (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and dried. Approximately 50 mg of each washed and dried hair sample was weighed into a reinforced microtube, and five 4 mm steel beads were added for grinding. Samples were then ground (2 × 5 min) using a Spex SamplePrep 5100 grinder (Spex, Metuchen, NJ, USA). One ml of methanol was added to ground hair samples and cortisol was extracted overnight with gentle shaking. Samples were then centrifuged to collect hair and supernatants were transferred to fresh tubes and evaporated to dryness. Samples were reconstituted in 0.3 mL of PBS and cortisol levels determined by EIA. Recovery was determined at the same time as sample analysis and used to adjust final sample cortisol values. Inter-assay variation was 9.4%. Intra-assay variations for batches one to four were 3.0%, 8.4%, 5.4%, and 4.4%, respectively.

FGM and Fecal sIgA

Spontaneously voided fecal samples were collected the night before or the morning of each testing day using plastic baggies provided to the breeder before each visit. If breeders were unable to collect feces, experimenters did so upon their arrival. Breeders typically isolated dams in an indoor or outdoor pen to obtain feces at the 6 W Pre and 8 W Post time points if they were group-housed. Short periods of isolation, variation in collection times, and diurnal changes in cortisol concentrations would likely not have influenced results as fecal metrics capture changes over a longer timeframe36. Due to the number of puppies enrolled in the study and the labor-intensive nature of metric collection, feces could not be collected from every individual puppy. Instead, feces were collected from each litter (i.e., any feces voided in the pen containing the litter), and additionally, at 8 W Post, one focal puppy per litter that was randomly selected (random number generator). Feces from focal puppies were identified using blue food dye (Royal Blue Icing Color, Wilton, Woodridge, IL, USA) provided to the breeders at the 4 W Post visit. A pea-sized amount mixed with baby food (Turkey, Ham, or Chicken and Gravy; Gerber, Nestle, Florham Park, NJ, USA), was instructed to be given to them 10–12 h before the experimenters’ visit. If there was only one puppy in a litter at 8 W Post, their fecal sample was considered a focal puppy sample. Feces were stored in plastic baggies labelled with their respective identifications in Styrofoam coolers with ice packs while travelling to and from breeders, and, if available in accommodations on longer data collection trips, a refrigerator (approximately 1–3 °C). This ranged from approximately 4–84 h. Following travel, feces were stored in a freezer (-20 °C) until they were shipped to the laboratory for FGM and sIgA analyses.

The below methods to determine FGM and fecal sIgA concentrations were identical to those outlined in two previous studies involving the same population4,38.

FGM and Fecal sIgA Sample Processing

Fecal samples were shipped on dry ice to Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium Endocrinology Lab in four batches. Samples were thawed and processed separately for cortisol and sIgA. Processing for cortisol involved drying > 1 g of feces in a 60 °C oven for 48–72 h, to account for variation in fecal water content. Dried samples were pulverized into a fine powder and 0.5 g was extracted by mechanically shaking overnight in 5 mL of 80% v: v methanol. Samples were centrifuged at 3000× g for 15 min and the supernatant stored at − 20 °C until analysis. Processing for sIgA involved weighing 0.5 g of wet feces, adding 1.5 mL of PBS (524650, EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) containing protease inhibitor (cOmplete mini [1 tablet/10 mL PBS], Roche, Basel, Switzerland), vortexing for 30 s, and incubating for 60 min at room temperature (RT), prior to a double centrifugation step (3000× g 15 min). The supernatant was collected and frozen until sIgA analysis within 1 month.

Cortisol enzyme Immunoassay

Fecal cortisol concentrations were quantified by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) using an anti-cortisol antiserum (R4866) and cortisol-horseradish perioxidase (HRP) ligand (C. Munro, University of California, Davis, CA, USA). The polyclonal antiserum raised in rabbits was directed against cortisol-3-carboxymethyloxime (CMO), linked to bovine serum albumin and was shown to cross react with cortisol (100%), prednisolone (9.9%), prednisone (6.3%), cortisone (5%) and < 1% with androstenedione, androsterone, corticosterone, desoxycorticosterone, 11-desoxycortisol, 21-desoxycortisone and testosterone56. The EIA was performed according to the methods established by Munro & Lasley56. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm (SpectraMax ABS, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) and data extrapolated via 4-parameter curve fit using Softmax Pro 7.1 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Results of each sample were expressed as ng of cortisol per gram of dry mass feces (dmf).

Inter-assay coefficients of variation for the cortisol assay were 3.9% and 5.4% for internal controls at 54% (20 pg/well) and 33% (70 pg/well) binding, respectively, for the first batch, 5.5% and 7.7% for internal controls at 53% (25 pg/well) and 32% (75 pg/well), respectively; for the second batch, 3.42% and 4.48% for internal controls at 62.24% (20 pg/well) and 34.47% (70 pg/well) binding, respectively, for the third batch. An inter-assay coefficient of variation was not calculated for the fourth batch as there was only one assay.

sIgA enzyme-linked Immunosorbant Assay

Fecal sIgA concentrations were quantified by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) (E40-104-26, E101, Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX, USA) as follows: 96-well plates were coated for 1 h at RT with a 1:100 dilution of affinity purified goat anti-canine IgA antibody in 100 uL of coating buffer (0.05 M Carbonate-Bicarbonate, pH 9.6). Following coating, plates were washed five times (50 mM Tris, 0.14 M NaCL, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8.0) before adding 200 uL/well of blocking solution (50 mM Tris, 0.14 M NaCL, 1% BSA, pH 8.0) and storing overnight at 4°C. The next day, plates were washed five times before adding 100 uL/well of duplicate standards (15.6–1000 ng/mL) or samples and incubating 1 h at RT on a light-protected plate shaker (600 rpm). Plates were then washed an additional five times prior to adding 100 uL/well of a 1:75,000 dilution of goat anti-canine IgA: HRP in ELISA buffer (50 mM Tris, 0.14 M NaCL, 1% BSA, 0.05% Tween 20) and incubating for 1 h at RT on a light-protected plate shaker (600 rpm). A final wash step was performed before adding 100 uL/well of 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate solution and incubating the plate for 15 min at RT on a light-protected plate shaker (600 rpm). The reaction was stopped with 100 uL/well of 0.18 M H2S04 and absorbance was measured at 450 nm (SpectraMax ABS, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA) with data extrapolated via 4-parameter curve fit using Soft-Max Pro 7.1 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Results for each sample were expressed as mg of sIgA per gram (wet weight) of feces.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and RStudio version 2022.02.3 (RStudio Team, Boston, MA, USA) with \(\:\propto\:=\) 0.05.

Inter-rater reliability (IRR)

IRR was calculated for scores on the dam and puppy stranger approach and isolation tests. For all tests, scoring of nominal categorical variables (i.e., yes, or no) were analyzed using Cohen’s or Light’s Kappa (depending on the number of coders) implemented by the irr package57, and interpreted in accordance with McHugh’s58 guidelines: 0-0.20 = None, 0.21–0.39 = Minimal, 0.40–0.59 = Weak, 0.60–0.79 = Moderate, 0.80–0.90 = Strong, > 0.90 = Almost Perfect. Scoring of continuous numerical or ordinal variables were analyzed using intraclass correlations (ICC) implemented by the DescTools package59, and Koo and Li’s60 guidelines were utilized to interpret the data: ≤0.5 = Poor, 0.5-≤0.75 = Moderate, 0.75-≤0.90 = Good, ≥ 0.90 = Excellent. Additional information on how IRR was conducted and analyzed is available in the Supplementary Material (Sect. 2).

Descriptive statistics

Means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated for dams’ and puppies’ responses to behavioral testing and the physiological metrics collected at each time point.

Relationships between Dam and Puppy Metrics

Scores from the dam stranger approach test were converted to points as follows: Red = 0, Yellow = 1, Green = 2, Treat = 1, No treat = 0, Touch = 1. Points were summed to create an overall numerical score for each dam at each time point (maximum of 10 points). Scores from the puppy stranger approach test were converted to points as follows: Orientation (Yes = 1, No = 0), Approach (Approach = 2, Ambivalent Approach = 1, No Approach = 0), Modifier (Affiliative-Gregarious = 2, Affiliative = 1, Undisturbed = 0, Stationary = 0, Avoid= -1), Posture (Neutral = 1, Low = 0), Treat (Yes = 1, No = 0), Touch (Yes = 1, No = 0). Points were summed to create an overall numerical score for each puppy at each time point (maximum of 22 points). Further, body shake, elimination, lip lick, and paw lift frequencies were summed to create a “StressSum” score, as these behaviors have been previously validated as measures of acute stress in dogs45,61,62. Additionally, if HCC for a hair sample was below the limit of detectability (LOD), the formula LOD/2 was utilized to obtain a result (n = 5), as the data were skewed63,64. Finally, sex ratio was represented by the proportion of males in each litter and was calculated by dividing the number of males by the total litter size, and average weekly weight gains were calculated for each individual puppy using the weekly weights collected by breeders.

Associations between dams’ and puppies’ responses to stranger approach (at equivalent time points, and 6 W Pre for dams and 4 W Post and 8 W Post for puppies), behaviors during the isolation tests, dams’ HCCs and FGM concentrations at 6 W Pre and individual puppies’ birth weights and average weekly weight gains were explored using linear mixed-effects models and Wald’s tests. These were implemented by the nlme65 and car66 packages, respectively. Dam metrics were entered as fixed effects, and puppy metrics as dependent variables. Litter ID was entered as a random effect to prevent pseudo-replication. In all models, restricted maximum likelihood (REML) was employed.

The relationships between dams’ and puppies’ physiological metrics, and dams’ 6 W Pre FGM and HCCs and litter sizes were identified using linear regression models (lm function). Generalized linear regression models with binomial distributions and logit link functions were used to examine relationships between dams’ 6 W Pre FGMs and HCCs and sex ratios. For analyses involving litter size and sex ratio, all puppies born to each dam were included, regardless of whether they were excluded from other analyses due to cross-fostering, death, etc. (as described below). Dam metrics acted as fixed effects and focal puppy, or litter metrics as dependent variables.

Normality and heteroscedasticity of all models were checked using QQ plots, histograms, and plotting residuals against fitted values. Right-skewed data were log or square root transformed where appropriate. If this did not increase normality when implementing simple linear regression models, a generalized linear regression model with a gaussian distribution and log link function was performed. If the normality assumption was met but homoscedasticity was not achieved when using simple linear regression models, the sandwich67,68 and lmtest69 packages were implemented to calculate robust standard errors.

Results

When tested at the 6 W Pre time point, dams were 42 days ± a mean of 5 days prepartum (range = 57 to 28 days prepartum). Further, when tested at the 4 W Post time point, dams and puppies were 28 days ± a mean of three days (range = 28–37 days) postpartum/ old. Finally, when tested at the 8 W Post time point, dams and puppies were 56 days ± a mean of 2 days (range = 54–64 days) postpartum/ old.

IRR

Overall, observers reached an agreement of ≥ 0.80 (i.e., dam isolation test (two observers): mean ICC3k = 0.95; puppy isolation test (two observers): mean ICC3k = 0.90; dam stranger approach test (three observers): mean ICC3k = 0.88; puppy stranger approach test (two observers): mean Cohen’s Kappa = 0.83) on all test scores. Results for IRR analyses are listed in the Supplementary Material (Sect. 3, Tables S2-S5).

Descriptive statistics

Means, medians, standard deviations, and ranges for dams’ and puppies’ responses to behavioral testing and the physiological metrics collected at each time point are detailed in Tables S6 and S7 (Supplementary Sect. 4). Due to low exhibition (i.e., lower than an average of four seconds) by dams and/or puppies, body trembling, play, grooming, escape attempt, frozen, circling, and pacing durations were excluded from the final analyses of the isolation tests. Vocalization frequencies were not further explored as they could not be measured in puppies (see Table 1).

In addition, data from the visual physical health assessments were removed from the final analyses due to lack of substantial variation in scores (Supplementary Sect. 4, Tables S8 and S9).

Relationships between Dam and Puppy Metrics

Isolation test

There were significant positive associations between dams’ exploration and stationary durations, and puppies’ durations of the same behaviors (exploration: \(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 9.472, p = 0.002; stationary: \(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 5.226, p = 0.022) (Supplementary Table S10). In contrast, there were no significant associations between dams’ and puppies’ locomotion durations (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.543, p = 0.461), or dams’ and puppies’ StressSums (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.365, p = 0.546) during the isolation tests (Supplementary Table S10).

Stranger Approach Test

There were no significant associations between dams’ stranger approach scores at 6 W Pre and puppies’ stranger approach scores at 4 W Post (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.040, p = 0.842) or 8 W Post (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.090, p = 0.764), or between dams’ stranger approach scores at 4 W Post and 8 W Post and puppies’ stranger approach scores at equivalent time points (4 W Post: \(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.058, p = 0.810; 8 W Post: \(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.804, p = 0.370) (Supplementary Table S10).

8 W Post Puppy FGM

There was a significant association between dams’ and focal puppies’ FGM concentrations at 8 W Post (estimate: 0.0003, SE = 0.0001, p = 0.002) but there was no association between dam and litter (p > 0.05) FGM concentrations at 8 W Post (Supplementary Table S11). A significant association was found between dams’ HCCs at 6 W Pre and focal puppies’ FGM concentrations at 8 W Post (estimate: -0.021, SE = 0.007, p = 0.007) (Supplementary Table S11). There were no other significant associations (Supplementary Table S11).

4 W Post Puppy FGM

There was a significant association between dams’ HCCs and litter FGM concentrations at 4 W Post (estimate: 0.052, SE = 0.025, p = 0.053). There were no significant association between dams’ FGM concentrations and litter FGM concentrations at 4 W Post (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Table S11). As the models exploring the associations between dams’ FGM concentrations and HCCs at 6 W Pre, and litter FGM concentrations at 4 W Post were not normal, generalized linear regression models were utilized. No significant associations were found (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Table S12).

8 W Post Puppy sIgA

There were no significant associations between dams’ sIgA concentrations at 8 W Post or 6 W Pre and focal puppies’ or litter sIgA concentrations at 8 W Post (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Table S11).

4 W Post Puppy sIgA

Generalized linear regression models were utilized to explore the effect of dams’ sIgA concentrations at 4 W Post and 6 W Pre on litter sIgA concentrations at 4 W Post, as normality could not be achieved in the original models. No significant relationships were detected (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Table S12).

Puppy weight and litter health metrics

There were significant negative associations between dams’ HCCs at 6 W Pre, and puppies’ birth weights (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 3.908, p = 0.048) and average weekly weight gains (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 4.081, p = 0.043) (Supplementary Table S13). There were no significant associations between dams’ FGM concentrations at 6 W Pre and puppies’ birth weights (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.347, p = 0.556) or average weekly weight gains (\(\:\text{{\rm\:X}}\)2(1) = 0.111, p = 0.739) (Supplementary Table S10). Further, there were no significant associations between dams’ FGM or HCCs at 6 W Pre and litter sizes or sex ratios (p > 0.05) (Supplementary Tables S11 and S13).

Discussion

The current study suggests that in US CBKs, fear and stress in dams may affect some indicators of puppy welfare early in life, as evidenced by significant associations between the metrics that were obtained for both groups. Previous findings that reduced durations of exploration and stationary behaviors were associated with transportation stress in puppies from CBKs4 align with the idea that reductions in exploratory behavior may be indicative of fearfulness70.

The similarities between dams’ and their puppies’ responses to the isolation test may have been found for a variety of reasons. First, it is plausible that some associations between exploration and stationary durations in dams and their puppies found in the current study were due to genetic effects of breed, as dams and their puppies were of the same breeds. Multiple studies have indicated that certain breeds have a higher propensity to show fearfulness than others71. Further, puppies’ responses to stressors are partially heritable from their dams1, and their similar genetic makeup (beyond those related to breed-specific traits) may have contributed to their behavioral responses. Future studies should examine the effects of breed further with fewer and more balanced breed groups than were available in the current study. However, within-breed differences in behavioral responses exist71 and should be considered as well, as the associations between exploration and stationary durations in dams and their puppies found in the current study could also relate to individual variation in response to testing. Another explanation for the associations observed may have been the influence of maternal care and epigenetic mechanisms. For example, more fearful and neophobic dams are more likely to exhibit poorer maternal care12,22, which has been associated with increased behavioral signs of fear in offspring (i.e., longer latencies to eat, and shorter duration of exploration in novel test environments)11. Future studies should explore to what extent specific genetic and environmental factors might affect puppies’ behavioral responses to stressors under different circumstances and test settings. This may be accomplished by exploring the variation in puppies’ behavioral responses within and between litters and examining the differences between them. The lack of significant associations between dams’ and puppies’ locomotion durations and frequencies of behaviors indicative of stress may be partly due to limited mobility in puppies because of their age53. It should be noted that some puppies in the current study may not have been mobile enough at the time of testing to express some of the behaviors indicative of fear and stress that we measured. This may have constrained identification of some associations. Future studies should identify how associations between dam and puppy behavioral responses might change as a function of puppy maturation.

Given the positive association between dams’ and puppies’ responses to isolation, it was surprising that there were no significant associations between their responses to stranger approach. However, there are several possible reasons for this finding. First, the tests occurred in different contexts. For example, dams were tested in their home pens while puppies were tested in the isolation pen immediately after the isolation test. Therefore, the response of the puppy to the stranger approach test might have been confounded by a potential stress-buffering effect associated with puppies seeking out the person for comfort. Similar suggestions have been made by Romaniuk et al.4 and Boone et al.29. Investigators made the decision to test dams in their home pens to reduce their exposure to stressors throughout the study’s duration, as they were tested at multiple points throughout the peri-parturient period. Additionally, as has been suggested for the isolation test, the stage of physical development of puppies may have influenced their responses to stranger approach (i.e., ability to approach, demonstrate certain postures or avoid interacting)53, whereas this was not an issue with their dams. Further, many US commercial breeders provide their puppies with some degree of socialization, as indicated here and in a previous study72 in addition to taking advantage of canine behavior and welfare education programs and increasing their knowledge in these areas73,74. It is therefore plausible that some are implementing the information in their kennels, resulting in socialization practices that might have given puppies more or different experiences with unfamiliar people during early development than their dams at similar ages. If so, this might have diminished the strength of negative maternal effects on some puppies’ responses to stranger approach (i.e., lessened fear that might have otherwise more closely resembled that of their dams). Dams without early, positive exposure to unfamiliar people would likely have shown more fear in response to stranger approach as experiences (or lack thereof) during dogs’ fear and socialization periods in early life can permanently affect their behavioral responses throughout adulthood52,75. Thus, the lack of association between dams’ and puppies’ responses to stranger approach might be partially due to different early life experiences76.

The lack of association between dams’ FGM concentrations at 6 W Pre and focal puppies’ or litter FGM concentrations at 8 W Post suggests that more acute measures of cortisol during gestation, as captured by FGM, may not influence puppies’ FGM concentrations at this age. However, it is well-known that excess glucocorticoid exposure during fetal development (which could not necessarily be captured by FGM concentrations, as they are only representative of approximately 24 h of HPA activity) may influence HPA activity77,78. Therefore, in addition to the association between dams’ FGM concentrations at 6 W Pre and puppies’ FGM concentrations at 8 W Post, the association between dams’ HCCs at 6 W Pre and puppies’ FGM concentrations at 8 W Post was explored. The statistically significant negative association found between these two variables suggests that dams with higher baseline long-term HPA activation and presumably, long-term HPA activation occurring from early pregnancy until 1 week before gestation (see Sect. 3.3.8.) may have had puppies with lower basal cortisol concentrations at 8 weeks old. However, as we are uncertain about what events occurred 24 h prior to collection of feces, it is also plausible that puppies’ FGM concentrations may have captured responses to an acute stressor.

A possible mechanism behind the negative association we observed is fetal glucocorticoid programming, in which prenatal stress and/or excess glucocorticoid concentrations during gestation may alter offspring basal glucocorticoid concentrations and glucocorticoids in response to stressors79. Dams’ average HCCs at 6 W Pre were 20.42 pg/mg \(\:\pm\:\) 12.08 and ranged from 5.85 to 64.55 pg/mg (Supplementary Table S7), which is much higher than the average HCC of approximately 6 pg/mg found at pregnancy diagnosis in 15 Doberman Pinscher dogs from a breeding facility80. It is plausible that some dams in the current study had higher HCCs than average. However, as there are few studies that have explored HCC throughout this period, future studies should investigate HCCs in various populations and breeds to understand how they might influence values before results from previous studies are utilized as reference ranges.

Changes in offspring glucocorticoid production may occur via alterations in the expression of offspring glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors and may serve as an adaptive mechanism to increase an animal’s survival in response to stressors after birth79. Previous literature suggests that the relationship between prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids and offspring neuroendocrine outcomes is complex, and may depend on factors such as age, sex, and the stage and context in which a gestational stressor may have occurred78. Based on these factors, increased prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids may be associated with increased or decreased basal HPA activity or responsiveness to stressors in offspring77. Future studies should further explore how the factors listed above may affect the relationship between dams’ cortisol concentrations during gestation, puppies’ basal cortisol concentrations, and how they change in response to an acute stressor. Further, the association between dams’ longer-term cortisol concentrations during gestation and puppies’ longer-term cortisol concentrations after birth should be explored in future studies. Doing so may provide further insight into the complex relationship between dams’ and their puppies’ physiological stress responses. Moving forward, as hair could not be collected from puppies as a metric of longer-term HPA axis activation, other collection methods indicative of the same period that are feasible for both dams and puppies should be explored. Claw clippings may prove useful, as they can be collected non-invasively and cortisol concentrations have previously been extracted from them in adult dogs and young puppies81,82,83.

The current study also discovered a statistically significant positive association between dams’ and focal puppies’ FGM concentrations at 8 W Post. This suggests that shorter-term, basal concentrations of cortisol in dams and their puppies at equivalent time points are similar, even in the absence of lactation and being housed together. These findings are similar to those in human babies and their mothers. To illustrate, one study found that if mothers were breastfeeding at 3 months postpartum, their salivary cortisol concentrations at 12 months postpartum were significantly positively correlated with their baby’s, even though most mothers had ceased breastfeeding84. As has been suggested for our findings that dams’ and puppies’ responses to isolation were similar, it is plausible that this association may have been mediated by maternal care and epigenetic mechanisms10,12,22, or maternal genetics1,61. Future studies should examine whether these similarities reflect analogous physiological responses to particular events occurring in the kennel, such as weaning or introduction to new environments, as it is plausible that FGM concentrations may have captured HPA activity in response to an acute stressor such as these.

The statistically significant positive association between dams’ HCCs and litter FGM concentrations at 4 W Post may be related to relationships between nursing, other maternal behaviors, and basal cortisol concentrations in dams15,18, as well as glucocorticoids being passed via milk from dams to puppies85. This is supported by a previous study noting the association between more maternal care and increased basal concentrations of cortisol in puppies at postnatal week five18. Exploring these associations further may have important implications, as increased basal cortisol concentrations at postnatal week 5 have been associated with increased dominance and decreased fear and impulse control during training tasks in puppies at 1 year old18. As methods to quantify cortisol in canine milk exist85, future studies should incorporate milk samples from the dam as an additional metric. Doing so will provide researchers with insight into the proportion of puppies’ cortisol concentrations that are directly related to cortisol concentrations in dams’ milk vs. other factors such as possible HPA axis activation.

The finding of no significant associations between dams’ sIgA concentrations at 6 W Pre and 8 W Post, and puppies’ at 8 W Post is not surprising as both puppies and dams undergo major changes in immune function during these times. For example, dam immune function is thought to be suppressed throughout gestation86,87 and upregulated after weaning88. On the contrary, puppies rely on maternal antibodies until approximately 6–16 weeks old, which is dependent on the concentrations of immunoglobulins ingested from colostrum after birth89,90. After this point, puppies’ concentrations of major classes of immunoglobulins (i.e., IgG, IgA, IgM) mature until they reach adult-like levels at approximately 1 year of age89. The current study suggests that at the time points collected, the way in which these changes occurred in puppies may not have been dependent on concentrations in dams, and vice versa.

The most parsimonious explanation for the absence of a significant association between dams’ and litter sIgA concentrations at 4 W Post was the small number of samples. Coprophagia by the dam, which is a normal maternal behavior at this time point91, frequently occurred after puppies defecated, making it difficult for experimenters to obtain feces. Further, if only small quantities of feces could be collected (which was frequently the case), FGM analyses were prioritized over sIgA. If a larger number of samples had been collected, we would have expected to see a significant association between dams’ and puppies’ concentrations at 4 W Post, as IgA is found in canine milk92.

The finding of no significant associations between dams’ FGM concentrations at 6 W Pre and puppies’ weights suggests that, as previously discussed, this metric may be capturing more acute changes in dam stress that may not have a significant impact on puppies’ physical development. In contrast, the statistically significant negative associations between dams’ HCCs at 6 W Pre and puppies’ birth weights and average weekly weight gains suggests that higher long-term HPA activation during gestation may be associated with puppies’ physical development. Findings analogous to this have been observed in rats and rhesus monkeys93,94. Similar to the relationship between dams’ cortisol concentrations during gestation and puppies’ cortisol concentrations at 8 W Post, a potential mechanism behind these results may be fetal glucocorticoid programming. This occurs when maternal cortisol passes to the fetuses during gestation, which then affects the offsprings’ birth weights due to its catabolic actions95. However, it is important to note that factors other than dams’ long-term HPA activity during gestation may have impacted puppies’ litter health metrics. For example, characteristics of maternal diet during gestation and lactation may have affected the amount of milk puppies ingested, and subsequently their weights96. Further, the amount of colostrum ingested by the puppies from their dam may have been related to puppy weight gain97. Additionally, as a previous study found that dogs with higher growth rates early in life had higher social and physical engagement scores98, future studies should investigate how birth weights and average weekly weight gains during this time might affect puppies’ long-term welfare.

A limitation of the current study was its observational nature, which makes it impossible to determine causality for the statistically significant associations identified. Further, as previously discussed, we were unable to identify what events occurred in the kennel 24 h prior to fecal collection. Thus, it was difficult to disentangle whether FGM concentrations reflected basal cortisol concentrations or cortisol concentrations in response to an acute stressor. Additionally, most fecal samples in the current study were split into two equal parts before analyses of physiological metrics for current study. This procedure may have affected final concentrations, as concentrations of cortisol and sIgA are not evenly distributed throughout fecal masses in some species99,100,101. Furthermore, as previously discussed, cortisol concentrations in dams’ milk were not collected, which limited our ability to disentangle the mechanisms behind the positive association found between dams’ HCCs and puppies’ FGM concentrations at 4 W Post. Finally, as the current study was conducted in a subset of CBKs that volunteered their participation, there may have been an aspect of volunteer bias that somewhat reduces generalizability of the findings to the entire CBK population.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current study has relevant implications for breeding bitch selection, monitoring, and management in CBKs, as the findings suggest that dam fear and stress may influence some aspects of puppies’ responses to stressors. For example, breeders may choose to forego breeding dams who consistently display high levels of fear and stress in response to various stimuli that are typically present in the kennel environment. Doing so may not only support the welfare of dams throughout the peri-parturient period but ensure that any deleterious effects of maternal fear and stress on puppy welfare are not facilitated. Furthermore, this study provides new knowledge about associations between certain fear and stress-related metrics. These include relationships between behaviors elicited in response to mild stressors, such as encountering unfamiliar people or temporary isolation, and physical and physiological indicators of welfare state, such as cortisol concentrations, immune system activation, and physical development, in dams and puppies from CBKs. This information may be useful in that breeders and pet families who select these dogs can potentially ensure that they can successfully respond to challenges, such as ground transportation, when necessary, and other novel or potentially fear-inducing stimuli. This may support the dogs’ welfare both while housed in CBKs and when they are placed in their future homes. Future studies should identify specific factors that may negatively affect dam welfare throughout the peri-parturient period, especially during gestation, and develop interventions to mitigate them wherever feasible.

Conclusion

The current study provided evidence that fear and stress in dams may affect some metrics indicative of welfare in their puppies, such as responses to isolation, FGM, birth weights, and average weekly weight gains. The associations found between the responses of dams and their puppies may have been due to factors such as genetics, maternal care, environment, and early social learning, all of which require further exploration. Collectively, the current study’s findings have the potential to inform strategies to assess and improve the welfare of dams and puppies from CBKs and may have implications for their welfare when placed in homes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wilsson, E. & Sundgren, P. E. Behaviour test for eight-week old puppies - heritabilities of tested behaviour traits and its correspondence to later behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 58, 151–162 (1998).

Scott, J. & Fuller, J. The Inheritance of Behavior Patterns: Single-Factor Explanations. in Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog 261–294The University of Chicago Press, (1965).

Scott, J. P. & Bielfelt, S. W. Analysis of the puppy testing program. in Guide Dogs for the Blind (eds Pfaffenberger, C. J., Scott, J. P., Fuller, J. L., Ginsburg, B. E. & Bielfelt, S. W.) 39–75 (Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam, (1976).

Romaniuk, A. C. et al. The Effect of Transportation on Puppy Welfare from commercial breeding kennels to a distributor. Animals 12, 3379 (2022).

Bhowmik, N. et al. HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, Alabama,. Heritability and genome-wide association study of dog behavioral phenotypes in a commercial breeding cohort. in 11th International Conference on Canine and Feline Genetics and Genomics (2022).

Braastad, B. O. Effects of prenatal stress on Behaviour of offspring of Laboratory and Farmed mammals. Appl. Anim. Behav. 61, 159-180 (1998).

Braastad, B. O., Osadchuk, L. V., Lund, G. & Bakken, M. Effects of prenatal handling stress on adrenal weight and function and behaviour in novel situations in blue fox cubs (Alopex lagopus). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 57, 157–169 (1998).

Cooper, C., Evans, A. C. O., Cook, S. & Rawlings, N. C. Cortisol, progesterone and B-endorphin response to stress in calves. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 75, 197–201 (1995).

Maccari, S. et al. Prenatal stress and long-term consequences: implications of glucocorticoid hormones. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 27, 119–127 (2003).

Liu, D. et al. Maternal care, hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors, and hypothalamic- pituitary-adrenal responses to stress. Sci. (1979). 277, 1659–1662 (1997).

Caldji, C. et al. Maternal care during infancy regulates the development of neural systems mediating the expression of fearfulness in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95, 5335–5340 (1998).

Meaney, M. J. & Maternal Care Gene expression, and the Transmission of Individual Differences in Stress Reactivity across Generations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1161–1192 (2001).

Liu, D., Diorio, J., Day, J. C., Francis, D. D. & Meaney, M. J. Maternal care, hippocampal synaptogenesis and cognitive development in rats. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 799–806 (2000).

Foyer, P., Wilsson, E. & Jensen, P. Levels of maternal care in dogs affect adult offspring temperament. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–8 (2016).

Bray, E. E., Sammel, M. D., Cheney, D. L., Serpell, J. A. & Seyfarth, R. M. Effects of maternal investment, temperament, and cognition on guide dog success. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114, 9128–9133 (2017).

Guardini, G. et al. Influence of morning maternal care on the behavioural responses of 8-week-old Beagle puppies to new environmental and social stimuli. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 181, 137–144 (2016).

Guardini, G. et al. Influence of maternal care on behavioural development of domestic dogs (Canis Familiaris) living in a Home Environment. Animals 7, 93 (2017).

Nagasawa, M. et al. Basal cortisol concentrations related to maternal behavior during puppy development predict post-growth resilience in dogs. Horm. Behav. 136, 105055 (2021).

Champagne, F. A. & Meaney, M. J. Stress during Gestation alters Postpartum maternal care and the development of the offspring in a Rodent Model. Biol. Psychiatry. 59, 1227–1235 (2006).

Patin, V. et al. Effects of prenatal stress on maternal behavior in the rat. Dev. Brain Res. 139, 1–8 (2002).

Smith, J. W., Seckl, J. R., Evans, A. T., Costall, B. & Smythe, J. W. Gestational stress induces post-partum depression-like behaviour and alters maternal care in rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 29, 227–244 (2004).

Francis, D. D., Champagne, F. C. & Meaney, M. J. Variations in maternal behaviour are associated with differences in oxytocin receptor levels in the rat. J. Neuroendocrinol. 12, 1145–1148 (2000).

Slabbert, J. M. & Rasa, O. A. E. Observational learning of an acquired maternal behaviour pattern by working dog pups: an alternative training method? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 53, 309–316 (1997).

Fugazza, C., Moesta, A., Pogány, Á. & Miklósi, Á. Social learning from conspecifics and humans in dog puppies. Sci. Rep. 8, 9257 (2018).

Chesler, P. Maternal influence in Learning by Observation in Kittens. Sci. (1979). 166, 901–903 (1969).

Jaeggi, A. V. et al. Social learning of diet and foraging skills by wild immature bornean orangutans: implications for culture. Am. J. Primatol. 72, 62–71 (2010).

Gerull, F. C. & Rapee, R. M. Mother knows best: effects of maternal modelling on the acquisition of fear and avoidance behaviour in toddlers. Behav. Res. Ther. 40, 279–287 (2002).

Mineka, S., Davidson, M., Cook, M. & Keir, R. Observational conditioning of snake fear in rhesus monkeys. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 93, 355–372 (1984).

Boone, G., Romaniuk, A. C., Barnard, S., Shreyer, T. & Croney, C. The Effect of Early Neurological Stimulation on Puppy Welfare in commercial breeding kennels. Animals 13, 71 (2022).

Otovic, P. & Hutchinson, E. Limits to using HPA axis activity as an indication of animal welfare. ALTEX - Altern. Anim. Experimentation. 32, 41–50 (2015).

Broom, D. M. The scientific assessment of animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 20, 5–19 (1988).

Mormède, P. et al. Exploration of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal function as a tool to evaluate animal welfare. Physiol. Behav. 92, 317–339 (2007).

Blecha, F. Immune System Response to Stress. in The Biology of Animal Stress: Basic Principles and Implications for Animal Welfare (eds. Moberg, G. P. & Mench, J. A.) 111–122CABI Publishing, (2000).

Sheriff, M. J., Dantzer, B., Delehanty, B., Palme, R. & Boonstra, R. Measuring stress in wildlife: techniques for quantifying glucocorticoids. Oecologia 166, 869–887 (2011).

Kobelt, A. J., Hemsworth, P. H., Barnett, J. L. & Butler, K. L. Sources of sampling variation in saliva cortisol in dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 75, 157–161 (2003).

Schatz, S. & Palme, R. Measurement of Faecal Cortisol Metabolites in Cats and dogs: a non-invasive method for evaluating adrenocortical function. Vet. Res. Commun. 25, 271–287 (2001).

Staley, M., Conners, M. G., Hall, K. & Miller, L. J. Linking stress and immunity: Immunoglobulin A as a non-invasive physiological biomarker in animal welfare studies. Horm. Behav. 102, 55–68 (2018).

Romaniuk, A. C. et al. Dam (Canis familiaris) Welfare throughout the Peri-parturient period in commercial breeding kennels. Animals 12, 2820 (2022).

Stella, J., Shreyer, T., Ha, J. & Croney, C. Improving canine welfare in commercial breeding (CB) operations: evaluating rehoming candidates. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 220, 104861 (2019).

Rogowski, J. C. Effects of positive caretaker interactions on dog welfare in commercial breeding kennels. Purdue Univ. West. Lafayette Indiana. https://doi.org/10.25394/PGS.19678794.V1 (2022).

Fraser, D., Weary, D. M., Pajor, E. A. & Milligan, B. N. A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim Welf. 6, 187–205 (1997).

Bauer, A. E. et al. Developing and pilot testing the Field Instantaneous Dog Observation tool. Pet. Behav. Sci. 0, 1 (2017).

United States Department of Agriculture. Animal Welfare Act and Animal Welfare Regulations. (2019). https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_welfare/downloads/bluebook-ac-awa.pdf

Friard, O. & Gamba, M. BORIS: a free, versatile open-source event-logging software for video/audio coding and live observations. Methods Ecol. Evol. 7, 1325–1330 (2016).

Beerda, B., Schilder, M. B. H., Van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M., De Vries, H. W. & Mol, J. A. Behavioural, saliva cortisol and heart rate responses to different types of stimuli in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 58, 365–381 (1998).

Mariti, C. et al. Dog attachment to man: a comparison between pet and working dogs. J. Veterinary Behavior: Clin. Appl. Res. 8, 135–145 (2013).

Palestrini, C., Previde, E. P., Spiezio, C. & Verga, M. Heart rate and behavioural responses of dogs in the Ainsworth’s Strange Situation: a pilot study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 94, 75–88 (2005).

Prato-Previde, E., Custance, D. M., Spiezio, C. & Sabatini, F. Is the dog-human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’s strange situation. Behaviour 140, 225–254 (2003).

Mehrkam, L. R., Hall, N. J., Haitz, C. & Wynne, C. D. L. The influence of breed and environmental factors on social and solitary play in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Learn. Behav. 45, 367–377 (2017).

Tod, E., Brander, D. & Waran, N. Efficacy of dog appeasing pheromone in reducing stress and fear related behaviour in shelter dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 93, 295–308 (2005).

Barnard, S., Flint, H., Shreyer, T. & Croney, C. Evaluation of an easy-to-use protocol for assessing behaviors of dogs retiring from commercial breeding kennels. PLoS One. 16, e0255883 (2021).

Serpell, J., Duffy, D. L. & Jagoe, J. A. Becoming a dog: Early experience and the development of behavior. in The Domestic Dog (ed. Serpell, J.) 93–117Cambridge University Press, (2016). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139161800.006

Scott, J. & Fuller, J. The Development of Behavior. in Genetics and the Social Behavior of the Dog 84–116The University of Chicago Press, (1965).

Flint, H. E., Coe, J. B., Serpell, J. A., Pearl, D. L. & Niel, L. Identification of fear behaviors shown by puppies in response to nonsocial stimuli. J. Veterinary Behav. 28, 17–24 (2018).

Davenport, M. D., Tiefenbacher, S., Lutz, C. K., Novak, M. A. & Meyer, J. S. Analysis of endogenous cortisol concentrations in the hair of rhesus macaques. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 147, 255–261 (2006).

Munro, C. J. & Lasley, B. L. Non-radiometric methods for immunoassay of steroid hormones. Prog Clin. Biol. Res. 285, 289–329 (1988).

Gamer, M., Lemon, J. & Singh, I. irr: Various Coefficients of Interrater Reliability and Agreement. Preprint at (2019). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=irr

McHugh, M. L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 22, 276–282 (2012).

Signorell, A. & DescTools Tools for Descriptive Statistics. Preprint at (2015). https://cran.r-project.org/package=DescTools

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A Guideline of selecting and reporting Intraclass correlation coefficients for Reliability Research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163 (2016).

Beerda, B., Schilder, M. B. H., Van Hooff, J. A. R. A. M. & De Vries, H. W. Manifestations of chronic and acute stress in dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 52, 307–319 (1997).

Elliot, O. & Scott, J. P. The development of emotional distress reactions to separation, in puppies. J. Genet. Psychol. 99, 3–22 (1961).

Hornung, R. W. & Reed, L. D. Estimation of average concentration in the Presence of nondetectable values. Appl. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 5, 46–51 (1990).

Pleil, J. D. Imputing defensible values for left-censored ‘below level of quantitation’ (LoQ) biomarker measurements. J. Breath. Res. 10, 045001 (2016).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S. & Sarkar, D. & R Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. Preprint at (2021). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Fox, J. & Weisburg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression (Sage, 2019).

Zeileis, A. Econometric Computing with HC and HAC Covariance Matrix estimators. J. Stat. Softw. 11, 1–17 (2004).

Zeileis, A., Köll, S. & Graham, N. Various versatile variances: an object-oriented implementation of clustered covariances in R. J. Stat. Softw. 95, 1–36 (2020).

Zeileis, A. & Hothorn, T. Diagnostic checking in Regression relationships. R News. 2, 7–10 (2002).

Russell, P. A. & RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN EXPLORATORY BEHAVIOUR AND FEAR: A REVIEW. Br. J. Psychol. 64, 417–433 (1973).

Mehrkam, L. R. & Wynne, C. D. L. behavioral differences among breeds of domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris): current status of the science. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 155, 12–27 (2014).

Barnard, S. et al. Management and behavioral factors associated with rehoming outcomes of dogs retired from commercial breeding kennels. PLoS One. 18, e0282459 (2023).

Doerr, K. & Forum and Mini Symposium Anchor Canine Welfare Discussions in Science | Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine. (2022). https://vet.purdue.edu/news/annual-2022-two-day-forum-anchors-canine-welfare-discussions-in-science.php

Brown, A., Health & Genetics and Behavior Featured at Annual Canine Welfare Science Forum | Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine. (2019). https://vet.purdue.edu/news/health-genetics-and-behavior-featured-at-annual-canine-welfare-science-forum.php

Luescher, A. Canine behavior and development. in Canine and Feline Behavior for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses (eds Shaw, J. & Martin, D.) 30–50 (John Wiley & Sons Inc., (2014).

Wilsson, E. Nature and nurture—how different conditions affect the behavior of dogs. J. Veterinary Behav. 16, 45–52 (2016).

Moisiadis, V. G. & Matthews, S. G. Glucocorticoids and fetal programming part 1: outcomes. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 391–402 (2014).

McGowan, P. O. & Matthews, S. G. Prenatal stress, glucocorticoids, and Developmental Programming of the stress response. Endocrinology 159, 69–82 (2018).

Kapoor, A. et al. Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. J. Physiol. 572, 31–44 (2006).

Fusi, J. et al. How stressful is maternity? Study about cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate coat and claws concentrations in female dogs from mating to 60 days Post-partum. Animals 11, 1632 (2021).

Fusi, J., Comin, A., Faustini, M., Alberto, P. & Veronesi, M. C. The usefulness of claws collected without invasiveness for cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (sulfate) monitoring in healthy newborn puppies after birth. Theriogenology 122, 137–143 (2018).

Mack, Z. & Fokidis, H. B. A novel method for assessing chronic cortisol concentrations in dogs using the nail as a source. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 59, 53–57 (2017).

Veronesi, M. C. et al. Coat and claws as new matrices for noninvasive long-term cortisol assessment in dogs from birth up to 30 days of age. Theriogenology 84, 791–796 (2015).

Jonas, W. et al. The role of breastfeeding in the association between maternal and infant cortisol attunement in the first postpartum year. Acta Paediatr. 107, 1205–1217 (2018).

Groppetti, D. et al. Maternal and neonatal canine cortisol measurement in multiple matrices during the perinatal period: a pilot study. PLoS One. 16, e0254842 (2021).