Abstract

We report on conditions of invariance of the transmitted pattern in the propagation through a periodic waveguide, the incident wave having no effect on the intensity pattern of the transmitted field. This phenomenon is reminiscent of that observed when illuminating a disordered medium in the regime of Anderson localization, as a consequence of the contribution of a single transmission eigenchannel to the transmitted wave. It is shown that the freezing of the transmitted wave is not intrinsically related to the disorder and that, whatever the frequency, it can also be observed in a regular, periodic system, provided that at most one Bloch mode is propagating. Moreover, while all localized modes in a disordered medium are exponentially decaying, our periodic waveguide system offers the possibility of observing the freezing with propagating waves, hence without the counterpart of having a very low energy transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among the many striking wave phenomena that arise in disordered media and explain the undiminished interest in the field of wave physics over decades1,2,3,4, the single channel regime, although not the most famous, is nevertheless quite remarkable. Since the ratio between two successive transmission eigenvalues (TEVs) is large in the localized regime, the first (largest) one dominates all others, and so does the corresponding eigenchannel in the transmission problem. A consequence is that “the speckle pattern of the transmitted intensity is literally frozen”5, that is, at a given frequency, the speckle pattern is independent of the incidence conditions. The single-channel regime, with a frozen transmitted pattern, was experimentally evidenced with microwaves6,7,8. It has also been applied in optics within a two-dimensional disordered medium, serving as a signature of Anderson localization in a single configuration without the need for averaging over a statistical ensemble9.

Among the situations where TEVs are insightful, this insensitivity to incidence conditions in the localized regime is very particular: indeed, in most cases, TEVs are used for wavefront shaping, which reflects the capability of using the sensitivity to incident wave in the diffusive regime to control the transmitted field10,11,12,13,14,15.

Let us consider the typical scattering problem of a L-length disordered waveguide that connects two semi-infinite leads; see Fig. 1a,b. The wave incident on the disordered medium, as well as the resulting scattered waves in the leads, are decomposed over the set of \(2 N\), right- and left-going, propagating modes, and the transmission matrix \(\textsf{T}\) couples the transmitted wave components to those of the incident wave. Using the singular value decomposition, this matrix is written as the sum of rank one matrices:

where \(\tau _n\) are the TEVs and where the unit vectors \({\textbf {U}}_n\) (resp. \({\textbf {V}}_n\)) map the output (resp. input) field of the transmission eigenchannels to the leads propagating modes. In the localized regime, \(1 \gg \tau _1 \gg \tau _2 \gg \tau _3 \gg \ldots\)16,17,18, thus

following a single-channel behavior and, whatever the incident field, the pattern at the output will be that of the mode combination \({\textbf {U}}_1\).

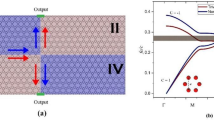

Invariance of speckle pattern of the transmitted field. (a,b) In a disordered waveguide, which length L is larger than the localization length \(\xi\), only one eigenchannel contributes to transmission, giving then the transmitted field its spatial pattern, regardless of the incident wave (here generated by a source \(\odot\) at two different positions in the waveguide)7,9. (c,d) A similar phenomenon can be observed with waves traveling through a periodic waveguide, in which at most one pair of right- and left-going Bloch modes is propagating while all others are evanescent.

Although the single-channel phenomenon is understood as being characteristic of the localized transport, the medium-induced reduction of the transmission problem to a rank-1 matrix is not intrinsically related to the disorder and can be observed in other complex media, such as periodic waveguides. Regardless of the geometric and structural complexity of the unit cell and the associated intricate wave interference phenomena it can induce, the discrete translational symmetry of the waveguide can lead to a single-channel regime, even at high frequencies where the wavelength is much smaller than the transverse length scale. Besides, whereas the localized transport leads to exponentially small transmission, the single-channel regime in a periodic waveguide can support propagating waves.

The scattering by a complex waveguide (either disordered or periodic) in the single channel regime can be schematically described by a multiple scattering process as shown in Fig. 2. Once the incident wave \(\psi ^\text {(in)}\) enters the inhomogeneous part of the waveguide (gray-colored region), it is first accompanied by a near field dependent on the incident wave (black arrows). However, going through a transition region, the wave is progressively encoded in the single right-going channel (orange arrows), with a complex scalar amplitude determined by the incident wave, but with a wave pattern determined only by the single right-going channel. Then, the wave filtered on the single right-going channel is reflected at the output end, with a (near field) reflection behavior independent of \(\psi ^\text {(in)}\). All the following multiple reflections and transmissions (orange arrows) obey the same reasoning, and consequently, the pattern of the total transmitted wave in the right lead is independent of \(\psi ^\text {(in)}\). This freezing process occurs regardless of the complexity of the field and without restriction on how strong the reflection at the output is.

Multiple scattering process in a finite waveguide of length L (gray region) within a single-channel regime. The waveguide is connected to two semi-infinite leads, with an incident wave \(\psi ^{(\text {in})}\) incoming from the left. Black arrows indicate waves that retain dependence on the pattern of the incident wave, while orange arrows denote waves that have lost information about this pattern.

Note that the scheme illustrated in Fig. 2 also applies to the case of two leads connected by a uniform waveguide segment where a single mode propagates (provided that the cross-section of this segment is small enough), leading to a simpler form of freezing (see Supplemental Material S5). However, in such a case, the single-channel regime, by nature, cannot be observed at high frequencies.

In this paper, we establish that whatever the incident wave, periodic waveguides can actually produce freezing of the pattern of the transmitted field [Fig. 1c,d] under proper frequency conditions for which it is shown theoretically that the transmission matrix can be reduced to a rank-1 matrix. Additionally, the inherent impedance mismatch leads to interference of right- and left-going waves in the periodic slab that is taken into account through a scalar form factor D that is potentially resonating. For frequencies such that the transmission matrix can be reduced to a rank larger than one, freezing by wavefront shaping is demonstrated.

Evanescent and propagating freezing

Let us consider a finite, d-periodic, waveguide [Fig. 1c,d] and numerically solve the propagation problem when a source (\({\varvec{\odot }}\)) is placed in the left lead with unit width at various positions to change the incident field. As in the above-mentioned disordered case, we assume that the semi-infinite leads at the left (\(x \le 0\)) and right (\(x \ge Md\)) of the \(M\)-cell scattering region supports \(2 N\) right- and left-going propagating modes. Denoting \(g_n(y)\), \(n = 1, \ldots , N\), the associated transverse eigenfunctions, the solution of the wave equation

at both ends of the scattering region is

where \({\textbf {g}} \equiv (g_n)\), \({\textbf {a}}^+\) (resp. \({\textbf {a}}^-\)) is the vector of the modal coefficient of the right- (resp. left-) going propagating wave, and \(\psi _\text {l,r}^\text {(e)}(y)\) denotes the evanescent fields at \(x = 0\) and \(Md\). Note that \(\psi ^\text {(in)}={{\textbf {g}}}^{\textsf {T}}(y) {\textbf {a}}^+(0)\). With a source located in the left lead (\(x < 0\)), \({\textbf {a}}^-(Md) = 0\) and

Fig. 3(a) shows the variations of the three largest TEVs, \(\tau _1> \tau _2 > \tau _3\) with the frequency k, in a range where \(N= 7\) modes are propagating in the leads.

(a) Spectrum of the first three TEVs \(\tau _1> \tau _2 > \tau _3\) of a 10-cell finite periodic waveguide (\(M= 10\), \(d = 2\)), in the frequency range \(k/\pi \in [6.20, 6.38]\). (b) Dispersion relation of the equivalent infinite periodic waveguide in the same range of frequency. The numbers in the right plot are the number of pairs of right- and left-going propagating Bloch modes in the corresponding gray colored frequency interval. Numerics are performed using a mode-matching method (see Supplemental Material S1 for more details on the calculations).

Following the reasoning stated in the case of disordered media, we can expect freezing of the pattern of the transmitted field if \(\tau _1 \gg \tau _2\): the single channel regime. This latter condition is realized when there is zero (band gap) or one propagating mode in the Bloch dispersion relation diagram (see Fig. 3b). The single channel regime is notably fulfilled in a frequency range around \(k = 6.23\pi\), where one Bloch mode is propagating, and the transmission through a 6-cell finite periodic waveguide at this frequency is illustrated in Fig. 4a with two examples, corresponding to two different positions of the point source generating the wavefield.

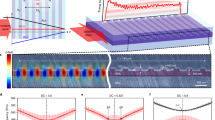

(a) Wavefield (modulus) in a finite periodic waveguide (\(M= 6\), \(d = 2\)), as generated by a point source located at two different positions (\({\varvec{\odot }}\)), at a frequency, \(k = 6.23 \pi\), in a band with only one pair of right- and left-going propagating Bloch modes (see. Fig. 3). (b) Pattern of the transmitted field \(|\psi (x = Md, y)|\), \(y \in [0, 1]\). (c) Similarity function F(x), as defined by Eq. (6). Numerics are performed using a finite element method (Comsol Multiphysics).

While the excitation, hence the incident wave, is modified from one case to the other, no significant change in the pattern of the transmitted field can be detected, see Fig. 4b. Only the overall amplitude of the transmitted wave remains dependent on the incidence conditions. Computing the wavefield in the whole waveguide allows us to go further than the only analysis of the pattern of the transmitted wave. Note that, even with different random patterns of the incident wave generated through a statistical ensemble, the pattern of the transmitted field remains frozen (see Supplemental Material S6). We can indeed observe the progressive freezing of the wave pattern as we move away from the source. This can be quantified with the similarity function

with h(x) being the width of the periodic waveguide. F(x) is a normalized scalar product (\(0 \le F \le 1\)) measuring the proportionality between the fields \(\psi\) and \(\psi '\) obtained with two different positions of the source. First low-valued close to the source [Fig. 4c], F(x) progressively increases towards 1, characterizing two similar patterns.

Another frequency range in which the condition \(\tau _1 \gg \tau _2\) is satisfied is around \(k = 6.35\pi\), see Fig. 3a. As shown in Fig. 5, choosing different positions of the point source, we also observe in this case, the freezing of the pattern of the transmitted wave [Fig. 5b].

(a) Wavefield (modulus) in a finite periodic waveguide (\(M= 6\), \(d = 2\)), as generated by a point source located at two different positions (\({\varvec{\odot }}\)), at a frequency, \(k = 6.353 \pi\), in a bandgap (see. Fig. 3). (b) Pattern of the transmitted field \(|\psi (x = Md, y)|\), \(y \in [0, 1]\). (c) Similarity function F(x), as defined by Eq. (6). Numerics are performed using a finite element method (Comsol Multiphysics).

Also, as in the preceding case, the evolution of the similarity function F(x) reveals how the freezing of the wavefield is completed after 3 or 4 periods. Figures 4 and 5, though both show the invariance of the transmitted field pattern with the incidence conditions, display nevertheless visible differences that can be interpreted by analysis of the dispersion relation, see Fig. 3b. Indeed, while the first frequency chosen, \(k = 6.23\pi\), lies in a band where one pair of Bloch modes are propagating, the second frequency, \(k = 6.353\pi\), lies in a bandgap. It follows that the wavefield amplitude is exponentially decreasing in this last case, whereas the wave is well transmitted through the waveguide in the first case. In this respect, this physical system differs significantly from an Anderson-localized medium in that it allows the field to be frozen while preserving a high transmission. Note that in the bandgap case, it would be possible to optimize the transmission by spatially shaping the incident wave19.

The occurrence of bands with one or zero pair of propagating Bloch modes that are wide enough to observe the freezing on a reasonable - not too long - distance is of course, highly dependent on the cell geometry. Targeting frequencies, or frequency intervals, at which the freezing occurs, would be possible by, e.g., optimization processes, but even without this, configurations allowing for a broadband freezing can easily be found, as illustrated in the Supplemental Material S2.

Theoretical analysis

The two examples in Figs. 4, 5 show how the freezing phenomenon appears as a consequence of the number of propagating Bloch modes, which itself correlates with the hierarchy of the first TEVs, as illustrated by Fig. 3. This can be further elucidated by a simple algebraic analysis of the scattering matrix. The transmission matrix of the \(M\)-cell system reads

where \(\Lambda\) is the diagonal matrix of the eigenvalues of Bloch eigenvalues associated with the right-going modes and \(\textsf{T}^\text {(l)}\), \(\textsf{R}^\text {(r)}\), \({\textsf{R}^\text {(l)}}'\) and \(\textsf{T}^\text {(r)}\) are elements of the scattering matrices of the left and right interfaces, mapping the Bloch modes to the lead propagating modes (see Supplemental Material S3). The inverted matrix term in Eq. (7) accounts for the multiple internal reflections that the wave experiences at the right and the left interfaces. That is clearly seen if this inverted matrix is rewritten as a Neumann series, \(\sum _{j=0}^{\infty }\left( \Lambda^M{\textsf{R}^\text {(l)}}' \Lambda^M\textsf{R}^\text {(r)}\right) ^{j}\), yielding the successive reflections described in the multiple scattering process in Fig. 2. If, after possibly being reordered, the Bloch eigenvalues are such that the first one, \(\Lambda _1\), is large compared with all others, then \(\textsf{T}\) can be approximated by the rank one matrix

with \({\textbf {T}}_1^\text {(r)}\) (resp. \({\textbf {T}}_1^{\text {(l)}\textsf {T}}\)) the first column (resp. row) of the transmission matrix of the right (resp. left) interface at \(x = 0\) (resp. L, see Supplemental Material S4). \({\textsf{R}_{11}^\text {(l)}}'\) and \(\textsf{R}_{11}^\text {(r)}\) are reflection coefficients of the first mode at these interfaces. Thus, as soon as one pair of Bloch modes, whether propagating or evanescent, predominantly contributes to the solution in the periodic waveguide, with all others being rapidly damped (\(|\Lambda _{\tiny 1}^{\tiny M}| \gg |\Lambda _{\tiny n\ge 2}^{\tiny M}|\)), then the pattern of the transmitted field \({\textbf {a}}^+(Md) \approx \tilde{\textsf{T}} {\textbf {a}}^+(0)\) no longer depends on the incident wave \({\textbf {a}}^+(0)\).

Indeed, from Eq. (8),

is collinear with \({\textbf {T}}_1^\text {(r)}\), whatever \({\textbf {a}}^+(0)\), where

is the form factor due to multiple internal reflections in the periodic slab that may lead to Fabry-Perot cavity resonances. We underline that only the amplitude in front of the transmitted vector \({\textbf {T}}_1^\text {(r)}\) (through the product \({\textbf {T}}_1^{\text {(l)}\textsf {T}} {\textbf {a}}^+(0)\)) can still vary with the incident wave.

Freezing by wavefront shaping

Suppose, now, that two right-going Bloch modes are propagating in the periodic waveguide (an example of such a band is given in Fig. 3 near \(k = 6.28\pi\)). Then,

where \({\textbf {u}}_{1,2}\) are linear combinations of the first two columns of \(\textsf{T}^\text {(r)}\) (see Supplemental Material S4) and \({\textbf {T}}_1^{\text {(l)}\textsf {T}}\) and \({\textbf {T}}_2^{\text {(l)}\textsf {T}}\) are the first two rows of \(\textsf{T}^\text {(l)}\). The transmitted field then reads as a linear combination of \({\textbf {u}}_1\) and \({\textbf {u}}_2\), and its pattern will thus depend on the incident wave \({\textbf {a}}^+(0)\). However, the transmission problem being now reduced to a rank-2 matrix, a freezing phenomenon can still be observed. Note that the coefficient of \({\textbf {u}}_1\) (resp. \({\textbf {u}}_2\)) in Eq. (11) is the first (resp. second) component of \(\textsf{T}^\text {(l)}{\textbf {a}}^+(0)\), that is, the amplitude with which the incident wave, when transmitted through the left interface, couples to the first (resp. second) propagating right-going Bloch mode. Therefore, any incident wave that does not couple to the first (resp. second) propagating right-going Bloch mode will give rise to a transmitted wave, the pattern of which is that of \({\textbf {u}}_2\) (resp. \({\textbf {u}}_1\)).

Fig. 6 illustrates this partial invariance of the transmitted field. Fig. 6a,b show the wavefield for two different incident waves (left subplots), none of which couple to the first incident Bloch mode.

Wavefield (modulus) in a finite periodic waveguide (\(M= 6\), \(d = 2\)) at a frequency, \(k = 6.284 \pi\), in a band with two right-going propagating Bloch modes, see Fig. 3. (a,b) Fields resulting from two different incident waves in the left lead, none of which couples to the first right-going propagating Bloch mode in the periodic region. (c,d) Fields resulting from two different incident waves in the left lead, none of which couples to the second right-going propagating Bloch mode in the periodic region. Numerics are performed using a mode-matching method (see Supplemental Material S1 for more details on the calculations).

The transmitted fields (right subplots), therefore, have an identical pattern. Now in Fig. 6c,d, if one chooses two other incident waves, none of which couple to the second propagating Bloch mode, then the transmitted field also displays an invariant pattern, but which differs from that of the first two cases. We have considered here a rank-2 transmission matrix, but the same freezing by wavefront shaping could be applied to rank-p transmission matrices as long as \(p <N\) (indeed, if \(p=N\), the sets of incident and transmitted waves have the same rank and no freezing is possible).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have shown that propagation through a periodic waveguide may result in the invariance of the speckle pattern of the transmitted wave with the incident wave. This property, which is usually observed in Anderson-localized disordered media, is here in contrast appearing due to the periodicity of the medium, as a consequence of the single-channel regime with a dominating transmission eigenvalue. The insensitivity to incidence condition is observed if at most one pair of right- and left-going Bloch modes is propagating in the finite periodic waveguide. This condition for freezing makes the periodic case significantly different from the disordered case in that it allows a non-weak transmission when the dominating mode is propagating. This should make it easier to experimentally evidence and characterize the transmission invariance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sheng, P. Introduction to Wave Scattering, Localization, and Mesoscopic Phenomena (Academic Press, 1995).

Beenakker, C. W. J. Random-matrix theory of quantum transport. Rev. Mod. Phys. 69, 731 (1997).

Akkermans, E. & Montambaux, G. Mesoscopic Physics of Electrons and Photons (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Rotter, S. & Gigan, S. Light fields in complex media: Mesoscopic scattering meets wave control. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015005 (2017).

Peña, A., Girschik, A., Libisch, F., Rotter, S. & Chabanov, A. A. The single-channel regime of transport through random media. Nature Commun. 5, 3488 (2014).

Wang, J. & Genack, A. Z. Transport through modes in random media. Nature 471, 345 (2011).

Shi, Z. & Genack, A. Z. Transmission eigenvalues and the bare conductance in the crossover to Anderson localization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 043901 (2012).

Davy, M., Shi, Z., Wang, J. & Genack, A. Z. Transmission statistics and focusing in single disordered samples. Opt. Exp. 21, 10367 (2013).

Leseur, O., Pierrat, R., Sáenz, J. J. & Carminati, R. Probing two-dimensional Anderson localization without statistics. Phys. Rev. A 90, 053827 (2014).

Vellekoop, I. M. & Mosk, A. P. Focusing coherent light through opaque strongly scattering media. Opt. Lett. 32, 2309 (2007).

Yılmaz, H., Hsu, C.W., Goetschy, A., Bittner, S., Rotter, S., Yamilov, A. & Cao, H. Angular memory effect of transmission eigenchannels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 203901 (2019).

Pai, P., Bosch, J., Kühmayer, M., Rotter, S. & Mosk, A. P. Scattering invariant modes of light in complex media. Nat. Photon. 15, 431 (2021).

Yılmaz, H., Kühmayer, M., Hsu, C. W., Rotter, S. & Cao, H. Customizing the angular memory effect for scattering media. Phys. Rev. X 11, 031010 (2021).

Bender, N., Yamilov, A., Goetschy, A., Yimlaz, H., Hsu, C. W. & Cao, H. Depth-targeted energy delivery deep inside scattering media. Nat. Phys. 18, 309 (2022).

Cao, H., Mosk, A. P. & Rotter, S. Shaping the propagation of light in complex media. Nat. Phys. 18, 994 (2022).

Muttalib, K. A. Random matrix theory and the scaling theory of localization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 745 (1990).

Pichard, J.-L., Zanon, N., Imry, Y. & Stone, A. D. Theory of random multiplicative transfer matrices and its implications for quantum transport. J. Phys. IV (France) 51, 587 (1990).

Stone, A. D., Mello, P. A., Muttalib, K. & Pichard, J.-L. Random matrix theory and maximum entropy models for disordered conductors. In Mesoscopic Phenomena in Solids (chapter 9) (eds Altschuler, B. L. et al.) (North Holland, 1991).

Uppu, R., Adhikary, M., Harteveld, C. A. M. & Vos, W. L. Spatially shaping waves to penetrate deep inside a forbidden gap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 177402 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.S., S.F., and V.P. conceived the idea, carried out the calculations and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salemeh, E., Félix, S. & Pagneux, V. Invariance of the speckle pattern of the transmitted wave in periodic waveguides. Sci Rep 15, 2504 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85971-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85971-7