Abstract

The aberrant vascular response associated with tendon injury results in circulating immune cell infiltration and a chronic inflammatory feedback loop leading to poor healing outcomes. Studying this dysregulated tendon repair response in human pathophysiology has been historically challenging due to the reliance on animal models. To address this, our group developed the human tendon-on-a-chip (hToC) to model cellular interactions in the injured tendon microenvironment; however, this model lacked the key element of physiological flow in the vascular compartment. Here, we leveraged the modularity of our platform to create a fluidic hToC that enables the study of circulating immune cell and vascular crosstalk in a tendon injury model. Under physiological shear stress consistent with postcapillary venules, we found a significant increase in the endothelial leukocyte activation marker intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), as well as enhanced adhesion and transmigration of circulating monocytes across the endothelial barrier. The addition of tissue macrophages to the tendon compartment further increased the degree of circulating monocyte infiltration into the tissue matrix. Our findings demonstrate the importance of adding physiological flow to the human tendon-on-a-chip, and more generally, the significance of flow for modeling immune cell interactions in tissue inflammation and disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tendons are a vital component of the human musculoskeletal system, connecting muscle to bone and transducing forces to produce movement1. Due to overuse and age-related degeneration, tendon injuries have become an increasingly significant clinical problem. Approximately 32 million cases of tendon injury are reported in the United States each year, accounting for 30% of musculoskeletal consultations and producing an estimated $30 billion economic burden due to healthcare expenses and loss of productivity2,3,4.

Healthy tendons are hypovascular with a relatively low population of cells and only 1–2% of the collagen matrix occupied by vessels5. In contrast, injured tendons are characterized by chronic inflammation leading to a vascularized fibrotic scar and impaired mechanical properties6. An increase in vasculature following tendon injury is associated with degeneration and is a key factor in promoting a chronic fibrotic response7. This dysregulated healing response is, in part, attributed to the increased activation of myofibroblasts by secreted cytokines released by tissue-resident immune cells, endothelial cells (ECs), and infiltrating leukocytes including neutrophils and monocytes. Collectively, the crosstalk between these key cells types within the fibrotic extracellular matrix is termed the myofibroblast microenvironment (MME)8.

The extent of neutrophil and monocyte infiltration following injury plays a key role in determining the progression of tendon repair toward scarring9. Within 2–3 days following injury, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels at the defect site increase several thousand times and drive the transendothelial migration of circulating leukocytes10. Among others, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) are primary cytokines upregulated in the post-injury microenvironment3,8. Tendon fibroblasts secrete a collagenous matrix containing chemotactic components, which further stimulates fibroblast migration, proliferation, and a transition to a myofibroblast phenotype11. However, the underlying mechanism of dysregulated tendon repair and the role of vascular cell types in the MME remains unclear. The need to elucidate the effects of infiltrating vasculature and immune cells has motivated the development of physiologically relevant tendon injury models8,12.

The majority of musculoskeletal models to date are high-cost, low-throughput animal models or over-simplified 2D in vitro models, both with limited translational value13. To enable the reductionist studies needed to understand the complex physiology of tissue microenvironments, microphysiological systems (MPS), or ‘tissue chips’, have emerged as paradigm-shifting technologies that mimic the essential features of human tissue in vitro. To begin addressing the debilitating impact of fibrosis following tendon injury, our laboratory developed a human tendon-on-a-chip (hToC) that features a 3D tendon hydrogel and a vascular compartment separated by a highly permeable and ultrathin nanomembrane to enable studies of cellular and molecular crosstalk between ‘vasculature’ and ‘tissue’ in the MME8. In our previous work, we established the hToC’s ability to replicate key fibrotic and inflammatory processes observed in vivo, including tissue contraction induced by myofibroblast activation, inflammatory cytokine secretion, transendothelial migration of monocytes, and vascular activation. Bulk RNA sequencing revealed significant concordance in transcriptional signatures between the hToC and human tenolysis tissue obtained from patients post-injury. Pathways related to matrix organization, integrin-mediated cell adhesion, and chemokine signaling were consistently enriched across the hToC and in vivo samples.

While able to recapitulate many of the salient features of injured tendon, the original hToC model is missing the important physiological elements of fluid flow and shear stress at the vascular wall. Both of these strongly impact endothelial cell morphology and function. The range of shear stress on the endothelium varies between 1 and 30 dynes/cm2 throughout the vascular network14. At the postcapillary venule, where immune cell extravasation is most prominent, shear stress falls within 1.5–4.5 dynes/cm215. Shear stress ≥ 10 dynes/cm2 promotes endothelial cell elongation and cytoskeletal alignment and improves barrier function16,17,18,19. Vascular flow also plays a vital role in the clearance of secreted inflammatory mediators and facilitates immune cell infiltration following the physiological cascade that involves rolling, arrest, and transmigration20,21. Thus, we aim to advance the hToC disease model to investigate the dynamic effects of vascular flow. We hypothesize that fluid flow will modulate the vascular inflammatory response in the hToC by impacting endothelial barrier function, surface adhesion protein expression, and the rate of immune cell infiltration.

To investigate this hypothesis, we developed a ‘manufacturable’ plug-and-play module that transforms the static hToC into a fluidic hToC enabling improved mechanistic studies of the vasculature. We validated, both computationally and experimentally, that the flow insert replicates physiological shear stress values and preserves characteristic endothelial morphology under applied shear stress. Importantly, we demonstrated that the endothelium exhibits distinct responses to inflammatory stimuli in static versus fluidic culture conditions and that vascular flow augments monocyte adhesion and transmigration. In the context of the complete hToC model, which includes a tenocyte-laden tissue compartment, we optimized a fluidic culture protocol and highlighted the importance of tissue macrophage-derived signaling in driving circulating monocyte infiltration. By incorporating the essential vascular cue of fluid flow, the fluidic hToC allows us to investigate the role of the vascular inflammatory response in fibrotic tendon pathology.

Results

Development of a peel-and-stick, manufactured flow insert for the hToC

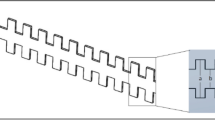

Our laboratory has developed a modular device platform for barrier tissue modeling with ultrathin porous silicon membranes termed the µSiM22. The hToC is an extension of the µSiM that replaces the bottom component with a thicker channel to model a 3D matrix tissue and employs dual-scale membranes23. A key advantage of our modular architecture is that the membrane and device components are commercially manufactured at scale, allowing the assembly of individual devices on demand in the laboratory. Assembly takes only minutes and involves activating pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSAs) by removing protective layers and pressing parts together in assembly jigs22. While we have previously developed and characterized a hand-crafted flow module for the µSiM20,24, here we sought to extend the scaled manufacturing and ‘peel-and-stick’ functionality of the modular µSiM to the fluidic hToC. We developed a simple and manufacturable flow module that: (1) creates an aligned flow channel over the membrane with flanking inlet and outlet ports and (2) includes a protected pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA) layer at the bottom of the channel that can be exposed and sealed against the membrane chip (Fig. 1a,b).

Manufactured flow insert development and validation. (a) Schematic of fluidic hToC device with flow insert and tubing, indicating inlet flow in red and outlet flow in blue across the ultrathin, silicon nitride nanomembrane. (b) Exploded view of flow insert layers: L1 = polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), L2 = pressure-sensitive adhesive (PSA), L3 = polyethylene terephthalate (PET), L4 = PSA. These four layers comprise the flow ports and flow channel. (c) COMSOL fluid dynamics simulation showing a shear stress map of the flow channel at a flow rate of 500 µl/min. The consistent shear stress over the boxed culture region confirms a uniform flow profile. (d) Representative 10 × 10 manufactured array of flow inserts, with inset showing a single flow insert unit. Image of fully assembled fluidic hToC, demonstrating phase imaging clarity of endothelial cell monolayer cultured in the flow channel. (e) Relative cell viability as measured by XTT assay of ECs cultured with insert-conditioned EGM-2 or X-VIVO media. Absorbance normalized to untreated negative control. We observed no differences in cell viability between the treatment conditions as tested by one-way ANOVA, confirming the biocompatibility of the flow insert materials.

Building on our previous approach20, we adapted our design to have a geometry compatible with commercial manufacturing and characterized flow throughout the device in COMSOL multiphysics software for target shear stress at the culture surface ranging from 1–10 dynes/cm2. The shear stress map (Fig. 1c) confirmed a uniform flow profile across the culture region and defined flow rates that achieve physiological shear stress levels in the device. Based on this design, prototype flow inserts were constructed in-house with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) via standard soft lithography techniques. These fully PDMS-based prototypes were sterilized with ethanol and the surface was activated with UV-ozone to enable adhesion to the membrane chip. After a 24 h curing period, the devices were fully sealed for fluidic experiments. Proving to be leak-proof and biocompatible, these ‘in-house’ flow inserts validated the basic design concept for advancement to manufacturing at ALine.

The final commercially manufactured flow insert (Fig. 1a,b) is composed of a 3 mm thick PDMS body with flow ports connected to a 200 μm tall flow channel. The flow channel comprises two PSA layers that encompass a polyethylene terephthalate layer. The total volume including the ports and channel is 4.23 μl (Supplementary Table S1). Parts are manufactured in a 10 × 10 array with bridging gates between individual inserts that are cut out upon receipt in the lab (Supplementary Fig. S1). The presence of a bottom PSA layer enables the desired peel-and-stick functionality with sealing and alignment achieved using the same jigs as for the hToC assembly. The protrusions on opposite sides of the insert ensure correct alignment in the open well, allowing the flow channel to fully encompass the porous membrane window and facilitate flow across the culture region (Supplementary Fig. S2). In our initial validation, we confirmed the efficiency of assembly (< 5 min), leak-proof performance (≥ 99%), and optical transparency for live cell imaging by phase contrast microscopy (Fig. 1d). To confirm biocompatibility and ensure the absence of cytotoxic leachates from the manufactured components, we performed an XTT viability assay in which in-house fabricated or commercially manufactured inserts were incubated in media types used in our tissue chip model (EGM-2, X-VIVO). The conditioned media was then added to human umbilical vein endothelial cells (ECs) in a 96-well plate, and the cells were cultured for 24 h before measuring cell viability. In both endothelial growth media and serum-free X-VIVO, we observed no differences in cell viability between the manufactured insert-treated group and the control group (Fig. 1e).

Demonstration of shear stress dependent EC alignment in manufactured inserts

Shear stress has been extensively shown to induce EC elongation and remodeling of actin fibers along the flow direction17,20. To validate that the manufactured flow inserts reproduce characteristic morphological alignment, we first tested EC biocompatibility by statically culturing ECs within the flow channel for 24 h. Live/dead staining revealed comparable cell viability (97.7 ± 0.6%) to that of the prototype in-house inserts (96.0 ± 1.0%) (Fig. 2a).

The manufacturable flow insert is biocompatible with endothelial culture and reproduces physiological cytoskeletal remodeling with fluidic shear stress. (a) Live/dead assay results of ECs cultured in either the manufactured or in-house insert showing comparable viability after 24 h of static culture in the flow channel (Live = green, Dead = red). (b) The peristaltic pump flow setup contains media reservoirs that serve as pulse dampeners on either side of the fluidic hToC device. (c) Phase images of ECs cultured in the fluidic hToC for 24 h of either static culture or physiological fluidic shear stress of 1.5 or 10 dynes/cm2. Black arrows indicate direction of flow. ECs were stained for F-actin to visualize cytoskeletal remodeling in response to flow. Radar plots quantify cell alignment relative to the flow direction. (d) Schematic demonstrating the definition of alignment angle, which is calculated as the angle between the flow axis and long axis of the cell. Quantification of percent of aligned cells, where alignment angle < 30º or > 150º is considered aligned along the flow axis. Increasing shear stress resulted in an increasing number of aligned cells. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

For flow experiments, we used a peristaltic pump circuit with fluidic capacitors to dampen oscillations and produce non-pulsatile flow23 (Fig. 2b). ECs were cultured for 24 h either statically or under fluidic shear stress on 5 µm dual-scale membranes with a type I collagen gel on the opposite side of the membrane. The microscale pores enable direct contact between the endothelial barrier and collagen matrix23. We selected a low shear condition of 1.5 dynes/cm2 to represent microvascular flow in the postcapillary venule and a high shear condition of 10 dynes/cm2 to reflect typical capillary flow14,15. Phase contrast imaging on the optically transparent membranes demonstrated cell elongation, further supported by immunofluorescence staining of F-actin (Fig. 2c). Radar plots illustrating the distribution of aligned cells across the culture region demonstrated a greater proportion of aligned cells in fluidic conditions compared to static cultures. We defined alignment angle as the angle between the long axis of the cell and the flow axis, and cells with an alignment angle < 30º or > 150º were categorized as aligned. Quantification in Fig. 2d revealed a shear stress-dependent increase in the percentage of aligned cells (30.4 ± 2.1% for static, 48.6 ± 4.0% for low shear, 78.7 ± 7.6% for high shear). These results established the capacity of the manufactured inserts to produce physiologically relevant shear stress-dependent cell alignment. Based on these results, we next sought to examine the consequences of fluid flow on cell physiology in the hToC, beginning with the molecular responses of endothelial cells.

Vascular flow improves barrier integrity and influences surface adhesion protein expression

Cell–cell junctions regulate endothelial barrier permeability to both solutes and circulating immune cells25. Junctional integrity depends on the function of adhesive proteins, such as VE-cadherin and PECAM-1, which are influenced by shear stress at the vascular wall26. In ECs cultured with 1.5 dynes/cm2 shear stress, we found that the VE-cadherin morphology was distinct from the continuous appearance in static cultures (Fig. 3a, inset) and exhibited a decrease in junctional gap width (Fig. 3b). The irregular junction lines in fluidic cultures represent morphological adaption to shear stress, as reported in other studies27,28. Additionally, we found that PECAM-1 staining in fluidic conditions was more consistent across the cell monolayer contrasting with the patchy and discontinuous expression observed in static cultures (Fig. 3a). Given the role of PECAM-1 in leukocyte transmigration29, its more uniform expression under flow may indicate an adaptive response to shear stress, which is important for improving barrier properties and enabling leukocyte trafficking.

Effect of fluid flow on surface and junctional adhesion molecule expression with or without TNF-α stimulation. (a) ECs cultured for 72 h, either statically or with 1.5 dynes/cm2 of fluidic shear stress. Junctions labeled with VE-cadherin (green) and PECAM-1 (red). Insets show an enlarged view of the VE-cadherin morphological differences between fluidic and static cultures. (b) Quantification of VE-cadherin junctional borders, demonstrating a significant decrease in width for fluidic cultures. Unpaired t-test was used to determine statistical significance, ****p < 0.0001. (c) ECs cultured with basal 10 ng/ml TNF-α stimulation for 24 h of static culture or fluidic shear stress of 1.5 or 10 dynes/cm2. ECs were preconditioned with 1.5 dynes/cm2 of shear stress for 24 h before stimulation. Devices were stained with ICAM-1 (green) and Hoechst (blue). (d). ICAM-1 expression is reported as the percent of cells with high, low, or no ICAM-1 levels. A fluorescence intensity threshold was set across all images to determine expression levels. Results indicate that a greater percentage of ECs express high levels of ICAM-1 in the 1.5 dynes/cm2 condition with TNF-α stimulation compared to static culture (p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test).

Next, we investigated the impact of preconditioning with flow on the inflammation-driven expression of the surface adhesion molecule ICAM-1, which mediates immune cell adhesion and transmigration30. For these experiments, we used TNF-α, a prominent cytokine in the tendon inflammatory milieu that promotes the upregulation of ICAM-1 on HUVECs31,32. ICAM-1 intensity levels were measured with immunocytochemistry and compared across six experimental groups: flow (24 h at low (1.5 dynes/cm2) or high (10 dynes/cm2) shear stress) or statically cultured with and without TNF-α stimulation. Our results demonstrated that both static and fluidic cultures maintained low baseline ICAM-1 expression in the absence of cytokine stimulation (Fig. 3c). However, TNF-α-stimulated ECs under low shear stress (1.5 dynes/cm2) accentuated ICAM-1 expression while high shear stress (10 dynes/cm2) attenuated ICAM-1 to levels comparable to unstimulated controls. The high shear stress results align with previous studies33, in which TNF-α-stimulated HUVECs subjected to 15 dynes/cm2 of fluidic shear stress exhibited a significant decrease in ICAM-1 intensity after 24 h of flow. Interestingly, under low shear stress conditions with stimulation, we found that the total percentage of ICAM-1-positive cells (82.0 ± 4.3%) was comparable to that under static-stimulated conditions (88.3 ± 2.7%) (Fig. 3d). However, when we further defined an intensity threshold of high versus low ICAM-1 expression to capture the heterogeneity across the monolayer, a significantly greater (p < 0.001) proportion of ECs displayed high levels of ICAM-1 expression under low shear stress conditions (31.5 ± 6.2% for low shear, 12.3 ± 4.1% for static; Fig. 3d). These findings highlight the complex interplay between flow-induced shear stress and inflammatory signaling, informing our subsequent studies on monocyte transmigration across the inflamed endothelium in the hToC.

Circulation enables modeling of the monocyte transmigration cascade

Monocytes infiltrating from the bloodstream are essential for the normal immune response after injury, but their excessive activation can lead to tendon fibrosis34. While our static hToC captured the role of infiltrating monocytes, the absence of physiological flow impacts endothelial-monocyte interactions35,36. To address this, we next developed a method to introduce circulating monocytes through the vascular flow channel. Because live imaging requires maintaining fluid flow outside the controlled environment of the incubator, we developed an optimized flow setup that enables real-time monitoring of circulating monocytes. This setup includes a bead bath to regulate the media reservoirs and an incubation stage to maintain 95% humidity and a temperature of 37 ℃ (Fig. 4a).

Establishing a live imaging setup to capture circulating monocyte transmigration with a ‘trench up’ membrane configuration. (a) Live imaging flow setup, which is comprised of a peristaltic pump, media reservoirs in a 37ºC bead bath, and an incubation stage that holds the device. This setup sits on a Nikon Ti2E microscope to capture real-time phase videos. Schematic of fluidic hToC with circulating monocytes. (b) Comparison of the flow channel geometry between ‘trench down’ and ‘trench up’ membrane configurations. Velocity profiles of an xz slice through the center of the channel, demonstrating a decreased flow velocity within the trench. (c) Schematic illustrating the steps in the monocyte transmigration cascade, which include static adhesion to the endothelium, probing, and transmigration across the barrier. (MCP-1: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1) (d) The final frame of a 2 h live video of monocyte circulation showing the EC monolayer with monocytes at various stages along the transmigration cascade. Color coding corresponds to the monocyte state along the transmigration cascade based on the phase appearance of the cells. Monocytes that appear phase-bright are on top of the endothelium, cells that are flattening out and probing appear gray, and cells that have transmigrated under the endothelium appear phase-dark.

In previous experiments, the membrane chips are oriented ‘trench down’, which creates a continuous channel across the porous window and surrounding regions (Fig. 4b). With shear stresses ranging between 1.5–4.5 dynes/cm2, the postcapillary venule is the primary site of immune cell transmigration, where monocytes exit the circulation and enter the injured tissue15. In the initial inflammatory stages of injury, a transient increase in vascular permeability leads to hemoconcentration which slows blood flow locally and enables leukocytes to gain access to the endothelium37. To mimic the slowing of blood flow at the postcapillary venule, we reoriented the chip to a ‘trench up’ configuration, which increases the vascular channel height by 2.5 times (Fig. 4b). We performed COMSOL simulations to model the altered shear stress profile (Supplementary Fig. S3) and defined a maximum flow rate to avoid off-target leukocyte activation, which occurs above 1.5 dynes/cm238,39. A table summarizing ‘trench down’ and ‘trench up’ shear stress values across a range of flow rates (10–1000 µl/min) is provided in Supplementary Table S2.

With these characterizations in place, we circulated human monocytes isolated from healthy donors at a flow rate of 50 μl/min which maintained a maximum shear stress throughout the channel below 1.5 dynes/cm2. The monocyte concentration in the flow circuit was optimized at 200,000 cells/ml according to representative levels of normal human blood counts40. We leveraged real-time phase microscopy, enabled by the glass-like imaging clarity of the membrane and transparency of the flow insert, to validate the monocyte transmigration cascade under flow in response to the tissue-side addition of MCP-1 over 2 h. The multistep transmigration cascade (Fig. 4c), regulated by shear flow, basal chemokines, and inducible adhesion molecules expressed by the endothelium32, was captured in real time (Supplementary Video 1). The time-lapse videos demonstrated key aspects of physiological monocyte transmigration, including rolling, arrest to the endothelial surface, and crossing of the endothelial barrier (Supplementary Video 2). Using phase imaging, we classified cells at different stages of the transmigration process41,42: phase-bright cells are on top of the endothelium, gray cells are flattening out and probing, and phase-dark cells have transmigrated under the endothelium (Fig. 4d). This analysis confirmed that the circulating system enabled by the manufactured flow insert successfully mimics the multistep interactions of immune cells at the vascular wall.

Circulation facilitates robust monocyte infiltration over a 24-h timescale

Since the complete hToC disease model is cultured for 24 h, we extended the timescale of monocyte circulation by live-labeling the monocytes and quantifying transmigration into the bottom channel with or without MCP-1. Confocal image reconstructions show an xz view of the devices (Fig. 5a), where monocytes adhering to the endothelium are highlighted in white and transmigrated monocytes are highlighted in orange. To quantify monocytes across the 3D volume, we utilized a classification tool in Imaris (Supplementary Fig. S5). We observed a striking increase in the number of transmigrated monocytes in the circulating condition with MCP-1, while we found a non-significant response to MCP-1 in static culture conditions (Fig. 5b). Additionally, we observed a significant increase (p = 0.0248) in the number of adhered monocytes in the circulating + MCP-1 condition, with non-significant differences in static culture (Fig. 5c,d). These results suggest that the addition of flow creates a steep chemotactic gradient between the top and bottom channels, enhancing the monocyte transmigration response and underscoring the importance of circulation in this context.

Monocyte circulation facilitates increased transmigration and adhesion compared to static conditions. (a) 3D volume reconstruction of confocal image stacks showing adhered (white) and transmigrated (orange) monocytes after 24 h of either static culture or circulation (50 μl/min) in fluidic hToC devices with endothelial barriers. 100 ng/ml MCP-1 was added to the bottom channel and compared to a control condition without MCP-1. (b) Quantification of transmigrated monocytes, normalized over the total image volume. Results demonstrate increased levels of monocyte transmigration in response to MCP-1 in the circulating condition, compared to non-significant changes in static culture. (c) xy slice at the membrane displaying monocytes adhered to the endothelium. (d) Quantification of adhered monocytes, normalized over the total image area. Circulating flow resulted in a significant increase (p = 0.0248) in monocyte adhesion. (e) Confocal images of adhered (white) and transmigrated (orange) monocytes after 24 h of flow (50 μl/min) in fluidic hToC devices with or without an endothelial barrier. In the corresponding phase images, the -EC condition displays the membrane with 5 µm pores and a collagen backfill, and the + EC condition demonstrates a representative EC monolayer prior to the introduction of monocytes. (f) Quantification of the total number of transmigrated monocytes, exhibiting a significant increase in monocyte transmigration in devices with an EC monolayer. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

To separate the influence of flow on the ECs and monocytes, we next compared the number of transmigrated monocytes in response to MCP-1 in devices with or without an endothelial barrier (Fig. 5e,f). We found that a significantly higher number of monocytes transmigrated in the presence of an endothelial monolayer (574.0 ± 173.1 compared to 72.8 ± 49.4 without an endothelial monolayer). These results point to the important role of ECs in recapitulating the physiological inflammatory response in the model. As part of our studies, we also compared monocyte transmigration across the endothelium seeded on dual-scale membranes with micropore sizes of 3 μm or 5 μm. Previously, we used 3 μm and 5 μm membranes for neutrophil31,41 and monocyte8 transmigration studies, respectively. Here, we found no significant differences in monocyte transmigration between these two micropore sizes (Supplementary Fig. S5), demonstrating that smaller pore sizes do not introduce additional resistance to monocyte migration and enabling the use of 3 μm membranes in future monocyte studies.

Monocyte transmigration and endothelial activation in response to cytokine stimulation under flow

To further dissect the circulating monocyte response to cytokines in the fibrotic secretome, we quantified monocyte transmigration across cytokine-stimulated ECs. ECs were preconditioned at 1.5 dynes/cm2 for 24 h, followed by the addition of TNF-α or TGF-β1 to the bottom channel with flow continued for another 24 h. Monocytes were then introduced at a flow rate of 50 µl/min and were recorded over 2 h using phase contrast microscopy to visually assess transmigration. In this device setup, ECs were cultured on nanoporous membranes that did not contain microscale pores. These membranes prevent monocytes from traveling into the bottom channel and facilitate the phase imaging analysis of monocyte migration state. Under control conditions, monocytes appeared phase-bright with a rounded morphology (Fig. 6a). In contrast, 63.9 ± 11.4% of monocytes appeared phase-dark with an elongated morphology in response to the TNF-α-stimulated endothelium (Fig. 6a,b). Interestingly, TGF-β1 stimulation did not induce a pro-migratory response and we observed a greater proportion of monocytes that remained phase-bright, with only 24.1 ± 8.2% transmigration. We additionally compared percent transmigration in response to MCP-1, a potent monocyte chemoattractant that is highly upregulated in the hToC milieu8. As expected, 55.4 ± 5.0% of the monocytes transmigrated, which was similar to what was observed in the TNF-α group. To investigate whether MCP-1 and TGF-β1 induce a combinatory transmigration response, we added MCP-1 to TGF-β1-stimulated ECs before monocyte addition. TGF-β1 + MCP-1 resulted in transmigration levels similar to those of MCP-1 alone (Fig. 6b), indicating that MCP-1 is primarily responsible for driving transmigration.

Monocyte transmigration and endothelial inflammatory response to key cytokines in the fibrotic secretome. (a) Monocytes circulated in EC-seeded fluidic hToC devices were observed in phase contrast time-lapse recordings over 2 h. Representative images of the final frame of the 2-h videos are shown. (b) Percent transmigration quantification of N = 3 experimental replicates per condition. Results demonstrated significantly elevated monocyte transmigration levels in response to TNF-α stimulated ECs compared to the negative control (p < 0.001) and TGF-β1 stimulation condition (p = 0.005). Similarly, MCP-1 and TGF-β1 + MCP-1 induced significantly increased percent transmigration compared to the negative control (p < 0.001) and TGF-β1 stimulation condition (p = 0.020). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (c) Following the 2-h transmigration experiment, devices were stained for ICAM-1 (red), PSGL-1 (green), and Hoechst (blue). Representative images of devices with and without monocytes in each stimulation condition are shown. We observed a substantial increase in ICAM-1 upon TNF-α stimulation regardless of the presence of circulating monocytes. The MCP-1, TGF-β1, and TGF-β1 + MCP-1 conditions, on the other hand, did not induce ICAM-1 upregulation. However, upon monocyte circulation, we observed an increase in ICAM-1 expression in these three conditions.

We next assessed the levels of endothelial activation under the tested stimulation conditions (TNF-α, TGF-β1, MCP-1, TGF-β1 + MCP-1), both with and without the addition of monocytes, by performing immunocytochemical staining for ICAM-1 and PSGL-1. PSGL-1 is expressed by monocytes and facilitates rolling and attachment to the endothelium via EC selectins43. Compared to the control, TNF-α stimulation resulted in a substantial increase in ICAM-1 expression regardless of monocyte introduction (Fig. 6c). Consistent with the results of the transmigration quantification, TGF-β1 induced minimal ICAM-1 expression. Although MCP-1 alone did not upregulate ICAM-1, it led to increased monocyte adhesion (as shown by PSGL-1 staining) and high transmigration rates, which together resulted in EC activation. Similarly, we observed a marked increase in ICAM-1 in devices with circulating monocytes in the TGF-β1 + MCP-1 condition. Overall, these results indicate that strong EC activation contributes to monocyte transmigration and that monocyte transmigration can further lead to EC activation.

Tissue macrophages increase monocyte infiltration in the tendon-vascular disease model

Once we established a basic understanding of flow in EC-monocyte co-cultures, we sought to study its impact in the complete hToC model. This culture system includes a top vascular compartment with ECs and circulating monocytes, as well as a bottom tissue compartment composed of tendon fibroblasts (tenocytes) and tissue macrophages (tMφ) encapsulated in a type I collagen matrix (Fig. 7a). To incorporate flow, we established a culture timeline to ensure preconditioning of the endothelial monolayer and the introduction of circulating monocytes under flow (Fig. 7b). First, to establish a tissue-side culture, tenocytes and blood-derived monocytes were added to a type I collagen hydrogel at D-6 and cultured in X-VIVO media spiked with M-CSF to differentiate the monocytes into a naïve macrophage state. X-VIVO media was selected for the more complex hToC culture as it is serum free and has synthetically defined components, eliminating batch-to-batch variability. Although X-VIVO is formulated for the culture of hematopoietic and immune cells, we have previously demonstrated its feasibility in modeling key phenotypes of the inflamed myofibroblast microenvironment in the hToC8. At D-2 of the timeline, ECs were seeded through the flow insert, and the top component was mounted on a media reservoir according to previously established methods8. After 24 h of static culture to establish the EC monolayer, the tissue and vascular components were combined, and 1.5 dynes/cm2 shear stress was applied to the vascular channel. At D0, monocytes were added to the flow circuit, and the flow rate was reduced to 50 μl/min to avoid off-target activation. The adherens junctional staining in Fig. 3a is representative of the endothelial barrier maturation prior to combining the tissue compartment and introducing circulating monocytes through the vascular channel. These results confirm the formation of a stable endothelial barrier both in static conditions and after the application of fluidic shear stress.

Integration of vascular flow in the complete hToC culture. (a) Schematic illustrating key cell types represented in the hToC injury model. The fluidic vascular channel is composed of an endothelial monolayer and circulating monocytes. The bottom tendon compartment contains tenocytes and tissue macrophages embedded in a collagen matrix. (b) Culture timeline for the complete fluidic hToC model, including all four cell types (tenocytes, ECs, monocytes, and tissue macrophages). Tenocytes and monocytes were encapsulated in a collagen hydrogel and cultured in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) for 6 days. ECs were statically cultured in the vascular flow channel for 24 h and then preconditioned at 1.5 dynes/cm2 for 24 h. At this point, monocytes were added to the circulation for an additional 24 h. (c) Confocal images of hToC cultures with or without tissue macrophages (tMφ) in the tissue hydrogel after 24 h of monocyte circulation through the vascular channel (D1). All cells other than the EC monolayer were live-labeled with membrane dyes. Circulating monocytes are red, tenocytes are green, and tissue macrophages are purple. The presence of tissue macrophages drives circulating monocyte transmigration into the bottom channel. (d) Quantification of adhered monocytes, demonstrating a trending increase in adhered cells in the + tMφ condition. (e) Quantification of transmigrated monocytes, showing a significant increase (p = 0.0098) in monocyte infiltration with the presence of tMφ. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used, **p < 0.01.

To validate this timeline, we live-labeled tenocytes, macrophages, and circulating monocytes to visualize the culture at 24 h. The confocal volume reconstructions of the 3D culture environment present circulating monocytes, tenocytes, and tMφ labeled in red, green, and purple, respectively (Fig. 7c). From these images, we observed an increased accumulation of circulating monocytes at the endothelium in devices with tMφ and our quantification revealed a trending increase in the number of adhered monocytes (Fig. 7d). In the absence of tMφ, monocyte transmigration was limited, with < 100 transmigrated monocytes/mm3. In contrast, the presence of tMφ significantly increased (p = 0.0098) monocyte transmigration, with > 300 transmigrated monocytes/mm3 (Fig. 7e). This difference suggests that tissue macrophage crosstalk plays a critical role in promoting monocyte transmigration, likely through secreting factors such as MCP-1 and TNF-α to promote the transmigration process. In addition to monocyte migration from the vascular channel, we found that on average 7.5 ± 2.1 endothelial cells migrated into the tissue compartment after 24 h of culture (Supplementary Fig. S6). Given that this represents less than 1% of the endothelial cells that form the vascular barrier, monocyte migration predominates during the current culture timeframe.

Discussion

The colocalization of vasculature and infiltration of immune cells in the myofibroblast microenvironment are critical factors in the initiation and persistence of tendon fibrosis7. To understand vascular crosstalk within the MME, our group developed a barrier tissue system to model the tendon-vascular interface. However, the model’s static vascular component does not include the crucial physiologic factor of flow, which impacts endothelial barrier function and downstream inflammatory responses. In this work, we introduced and validated a fluidic human tendon-on-a-chip (hToC) to investigate endothelial-monocyte interactions under physiological shear stress. We developed a novel peel-and-stick flow component for easy assembly and commercial scalability. Our initial validation studies confirmed that the flow insert accurately mimics physiological shear stress, supports endothelial cell viability, and induces EC elongation due to cytoskeletal remodeling17. Using this validated system, we found that shear stress improved endothelial barrier integrity, with VE-cadherin and PECAM-1 reorganization. ICAM-1 expression on TNF-α stimulated ECs increased under low shear (1.5 dynes/cm2) but was reduced at higher shear (10 dynes/cm2). Monocyte transmigration was significantly enhanced by TNF-α and MCP-1 under flow, and tissue macrophages further amplified monocyte infiltration into the tissue with circulating flow. These results demonstrate the model’s utility in studying vascular inflammation and immune cell transendothelial migration dynamics in tendon fibrosis.

Microfluidic devices have been leveraged over the past two decades to study fluid flow and shear stress, but their widespread integration in MPS suffers from inaccessible fabrication requirements and rigid designs44,45. Building off of our previous development of the µSiM22 and hToC8 platforms, here we present a flow insert component that enables physiological flow in complex in vitro models. While other commercial tissue chips, such as the Emulate Chip-A1, include a fluidic channel and culture chamber for thicker gel-based models, the fixed geometries do not facilitate a contractile hydrogel as in our hToC platform. Further, the glass-like imaging capabilities of our ultrathin (~ 100 nm) silicon nitride membranes offer advantages in monitoring dynamic immune cell adhesion and transmigration events in high resolution. The modularity of the fluidic hToC allows us to culture the tissue compartment statically for six days and easily integrate the fluidic vascular compartment to apply shear stress at the vascular barrier. Beyond modeling the role of the vasculature in the MME, the fluidic hToC can be adapted as a versatile barrier tissue platform for a variety of applications, including T cell migration in the context of multiple sclerosis46 and neutrophil trafficking47 across the blood–brain barrier.

Leveraging the fluidic hToC platform, we confirmed that flow improved endothelial barrier properties, and we observed an intriguing relationship between shear stress magnitude, inflammatory challenge, and ICAM-1 expression. With low shear stress and TNF-α stimulation, the number of ECs with high levels of ICAM-1 expression was markedly greater than that of static stimulated ECs. These results align with vascular physiology where the reduced shear environment in postcapillary venules is the site of ICAM-1 mediated recruitment of leukocytes48. In contrast, ICAM-1 expression was abrogated at high shear levels under inflammatory conditions, returning levels to baseline. We also investigated whether a lack of EC preconditioning with shear was important for preventing ICAM-1 upregulation under inflammatory conditions at high shear (10 dynes/cm2). Even without preconditioning, we found that high shear results in baseline levels of ICAM-1 expression as seen in static cultures (Supplementary Fig. S4). Chiu et al. reported similar anti-inflammatory effects on the EC response to inflammatory stimuli with and without preconditioning at 20 dynes/cm249.

Infiltrating immune cells from the vasculature, specifically monocytes, play a significant role in perpetuating the inflammatory response following tendon injury50. As the vasculature transitions from the capillary bed to the venule, there is a doubling in vessel diameter as well as a slowing of blood flow to enable immune cell engagement with the endothelium during inflammation. To simulate this geometric expansion from the capillary to the postcapillary venule, we leveraged a unique feature of the ultrathin nanomembranes. Inverting the chip compared to our prior work8,18,23,38 resulted in an expansion of the flow channel height from 200 to 500 μm directly above the membrane, enabling immune cell engagement and migration across the vascular barrier. With this membrane configuration, we established the critical roles of both circulating flow and the endothelial barrier in facilitating leukocyte adhesion and transmigration events. Our results indicated that fluidic shear stress not only enhances the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules but also promotes leukocyte rolling and adhesion. These factors together encourage a migratory leukocyte phenotype51. In the post-injury response in vivo, chemokines including MCP-1 are secreted by ECs, fibroblasts, and macrophages to selectively recruit monocytes from the bloodstream. The glycocalyx on the apical EC surface along with matrix proteins on the basal side provide the necessary barrier function to maintain the MCP-1 gradient and facilitate transendothelial leukocyte migration into the tissue52,53. These points highlight how the endothelial monolayer preserves the chemokine gradient in the hToC to guide leukocyte migration—an effect that may not occur without the vascular barrier.

Interestingly, we demonstrated that MCP-1 alone does not lead to EC activation, despite it producing a high degree of monocyte transmigration. This was most notable in the MCP-1 and TGF-β1 + MCP-1 conditions, where the basal introduction of MCP-1 did not upregulate ICAM-1 expression on the endothelium. With the addition of monocytes to the MCP-1 and TGF-β1 + MCP-1 conditions, we observed positive expression of PSGL-1 as well as ICAM-1 upregulation. These observations can be explained by the role of PSGL-1 in triggering inflammation and increased ICAM-1 expression54. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have directly investigated the effect of MCP-1 on ICAM-1 expression in human ECs, although the functions of MCP-1 extend beyond chemoattraction55. It has been reported that IL-1 and IL-6 are upregulated by human monocytes upon MCP-1 stimulation56,57, both of which have been implicated in the upregulation of ICAM-1 on ECs58,59. By further analyzing the secretome, we can elucidate the cytokines involved in the ICAM-1 upregulation we observed upon monocyte circulation. Maus et al. reported that MCP-1 increases monocyte adhesion to TNF-α-stimulated ECs under flow60. In contrast to these findings, we did not observe a co-stimulatory effect of TGF-β1 and MCP-1 in the co-culture conditions explored here. These results likely point to TGF-β1 as a modulator of tissue-sided responses, a question that we probed with the addition of tendon cell types in the bottom channel of the fluidic hToC.

We ultimately incorporated circulating monocytes in the complex cellular microenvironment of the complete hToC model. We found that the presence of tissue macrophages drives a more robust circulating monocyte response into the tissue compared to devices without tissue macrophages. These results are consistent with the documented resident macrophage response in the injured tendon, in which macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, MCP-1, and IL-661. The formation of chemokine gradients and the upregulation of adhesion molecules on the endothelium leads to the recruitment and infiltration of monocytes into the injury site62. We posit that these factors promoted the increased monocyte adhesion and infiltration we observed in the hToC. With these advancements in place, we plan to leverage the fluidic hToC as a platform to investigate immunomodulatory therapeutics in future studies. Natalizumab is an FDA-approved drug that affects leukocyte tethering and rolling on activated endothelium63 and Cenicriviroc blocks the binding of MCP-1 to CCR264. By administering these drugs in the hToC we aim to evaluate the suppression of vascular inflammation and fibrotic phenotypes.

We have demonstrated the fluidic hToC’s capability to investigate cellular crosstalk within the vascular inflammatory and myofibroblast microenvironments. However, several limitations and potential directions for future research remain to be addressed. The flow insert as constructed can only accommodate a straight vascular channel, precluding the investigation of the impact of vascular curvature on monocyte transmigration. Curved regions of the vasculature are known to create complex flow profiles that can alter endothelial gene expression and leukocyte transmigration dynamics65,66. To more closely replicate the in vivo environment, future iterations of the hToC could incorporate curved flow channels as well as self-assembled microvasculature in the tendon hydrogel. While self-assembled microvasculature systems67,68 mimic the natural architecture and remodeling processes of blood vessels, our membrane-based system offers enhanced control and reproducibility for dynamic endothelial cultures under precisely controlled shear stress. It has been reported that self-assembled microvessels subjected to continuous flow cause matrix remodeling and structural instability69,70. Fibrin gels often used in self-assembled platforms suffer from batch-to-batch variability that may impact gel formation and mechanical properties. Conversely, the flow insert enables consistent endothelial culture and the application of reliable fluid shear stresses on our membranes. Our observation of limited EC migration over 24 h presents an interesting future direction to explore neovascularization over an extended culture timeframe, allowing us to integrate the benefits of both approaches to achieve a more comprehensive model of the vasculature in the hToC.

We chose HUVECs to model the vascular barrier as they are a well-established cell type for in vitro systems. However, HUVECs may not represent the distinct permeability and response to shear stress across different sections of the vasculature. To enhance the physiological relevance of the model, future hToC studies will incorporate iPSC-derived endothelial cells differentiated from patient fibroblasts. In addition to the important factor of fluidic shear stress at the vascular wall, pathologic changes in matrix stiffness impact the mechanobiological response during tendon repair10. Tuning hydrogel parameters (e.g. collagen I/III ratio) could facilitate studies on the impact of matrix composition on myofibroblast differentiation and subsequent immune cell dynamics, such as monocyte migration distance71. Although the existing flow setup is low throughput, the manufactured flow insert developed and validated in this study provides a foundation for scaling up the fluidic hToC. Future efforts will focus on multiplexing fluidic devices to facilitate higher throughput screens of tissue microenvironments under flow.

Overall, we have demonstrated that vascular flow is essential for replicating the complex interactions between circulating immune cells and the inflamed vasculature in a model of the myofibroblast microenvironment. By integrating circulating flow into the hToC, we can more accurately evaluate therapeutics aimed at limiting immune cell infiltration and mitigating myofibroblast activation to resolve tissue fibrosis.

Methods

Nanomembranes

Silicon nitride nanomembranes manufactured by SiMPore, Inc. (Henrietta, NY) were used as substrates to culture endothelial cells in the hToC device. Both nanoporous and dual-scale membranes were used in this study. Nanoporous membranes are ~ 100 nm thick, contain ~ 60 nm diameter pores, and have a porosity of ~ 15%. Dual-scale membranes have the same thickness and nanoporosity but additionally contain 5 µm micropores that add an additional porosity of ~ 2%.

Fluidic hToC components

The top component, bottom component, and flow insert were manufactured at ALine Inc. (Signal Hill, CA) via laser cutting, lamination, and molding processes compatible with mass production (hundreds to tens of thousands). Top and bottom components were shipped as single units, while the flow inserts were shipped as 10 × 10 arrays. Individual flow inserts were removed from the array by cutting connecting gates with a razor blade. The flow insert and top component contain access ports to the top flow channel and bottom channel, respectively. All ports can be accessed with P20/P200 pipette tips (VWR, 76322–516). Assembly of top and bottom components was performed in a sterile biosafety cabinet as previously described8. Briefly, the protective masking layers that maintain component sterility during shipment were removed. The nanomembrane chip was placed on a custom assembly jig in an inverted or non-inverted orientation using notched tweezers. The top component was then placed over the nanomembrane and pressed firmly to form a tight seal. The bottom component was placed in a separate jig to bond it to the top component. Flow inserts were sprayed with 70% ethanol before being placed in the biosafety cabinet channel side up. The assembled top and bottom components along with the flow inserts were sterilized by 15 min of UV exposure in the biosafety cabinet. After UV sterilization, the inserts were rinsed 3 times with sterile 1X PBS, and any excess liquid was removed with a pipette. Using straight-tipped tweezers, the protective lining was removed to expose the pressure-sensitive adhesive on the bottom of the insert. The insert was aligned in the open well of the top component and pressure was applied with the flat side of the tweezers around the perimeter of the insert to activate the adhesive (see supplementary Fig. 1). The device is now fully sealed and ready for cell seeding and flow experiments.

A custom peristaltic pump circuit was assembled as previously described20. The components included 0.02″ ID silicone tubing (VWR, MFLX95802), 21 gauge NT dispensing tips (Jensen Global, JG21-1.0HPX, JG21-1.5HPX-90), and 5 ml vials. A peristaltic pump was used for circulating flow (Langer Instruments, USA).

COMSOL multiphysics simulation

A fluid dynamics simulation was performed in COMSOL Multiphysics to model the fluid profile in the flow insert channel. Laminar flow physics was applied to the channel geometry, and a no-slip boundary condition was selected at the walls. The inlet flow rate was set to a constant value and was simulated across a range from 10 to 1000 µl/min. A pressure P = 0 was applied to the outlet. A physics-controlled mesh was generated and a stationary parametric sweep study was executed to generate shear stress and velocity profiles.

Cell culture protocols

Cryopreserved pooled human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were purchased from Vec Technologies Inc. and expanded in T-25 flasks (Corning Inc., 430,639). HUVECs were cultured in EGM-2 Endothelial Cell Growth Medium (Lonza, CC-3162) and used between passages 2 and 6. Cells were maintained under standard culture conditions (37ºC, 5% CO2, 95% humidity). For device seeding, the backside of the nanomembrane was first coated with collagen (TeleCol-3, Advanced Biomatrix, 5026) and crosslinked in the incubator for 15 min. The flow channel and culture surface were then coated with 5 µg/cm2 of human fibronectin (Bio-Techne, 1918-FN-02 M) for 1 h at room temperature to facilitate cell attachment. Fibronectin supports cell adhesion and survival, facilitating the formation of a confluent monolayer after 24 h of culture on the nanomembrane18,23,31,41,42. HUVECs were then seeded at 40,000 cells/cm2 by infusing a cell suspension at 2 × 106 cells/ml and cultured statically for 24 h before starting fluid flow or adding inflammatory stimuli.

For the HUVEC shear conditioning studies, the peristaltic pump was set to a flow rate of 50 or 540 µl/min for low (1.5 dynes/cm2) and high (10 dynes/cm2) shear stress conditions, respectively. Devices were assembled with a ‘trench up’ membrane configuration for monocyte studies, and the flow rate was maintained at 50 µl/min (see supplementary Table 1 for shear stress comparisons). For ICAM-1 studies, HUVECs were basally stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α (R&D Systems, 210-TA) for 18 h. For live monocyte transmigration studies, HUVECs were basally stimulated with either 10 ng/ml TNF-α or 10 ng/ml TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, 240-B-002) for 18 h prior to monocyte addition. 100 ng/ml of MCP-1 (R&D Systems, 279-MC) was infused into the bottom channel of devices immediately before monocyte addition.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation and CD14 + monocyte sorting

Monocytes were isolated from blood drawn from healthy donors with informed consent before each experiment according to an approved protocol by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board (STUDY0004777). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. First, the PBMC layer was isolated from whole blood samples via density separation with 1-Step Polymorphs (Accurate Chemical & Scientific Co., Westbury, NY). The PBMCs were washed twice by centrifuging at 350 × g for 7 min at 15 ℃ with sterile-filtered wash buffer consisting of HBSS (Gibco, 14,175,095), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco, 15,630,080), and 5 mg/ml BSA (Cell Signaling, 9998S). Red blood cells were then lysed by the addition of 1/6X PBS for 1 min, followed by 4X PBS and a 7-min spin at 350 × g. An additional wash step as above was performed before the pellet was suspended in isolation buffer consisting of 1X DPBS (Gibco, 14,190,250), 2 mM EDTA (Gibco, 15,575,020), and 1 mg/ml BSA. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer, spun down at 300 × g for 3 min, and suspended in 80 µl of isolation buffer. To sort monocytes, CD14 microbeads (Milltenyi Biotec, 130–050-201) were added to the cell suspension and incubated at 4 ℃ for 15 min. A QuadroMACS™ separator was assembled with an LS column (Milltenyi Biotec, 130–042-401). After centrifuging the cells and microbead suspension again at 300 × g for 3 min, the cells were suspended in 500 µl of isolation buffer and added to the LS column. CD14 + monocytes were then flushed out of the column and used in experiments within 3 h of blood collection.

Fluidic hToC culture

The complete hToC quad culture was prepared as previously described8 with modifications for fluid flow (see Fig. 7A). Cells were labeled with DiI (circulating monocytes), DiO (tenocytes), and DiD (tissue macrophages) from the Vybrant Multicolor Cell-Labeling Kit (Invitrogen, V22889). First, tenocytes isolated from tendon tissue under an approved Institutional Review Board protocol (STUDY00004840) were suspended in a collagen hydrogel at 500,000 cells/ml. Freshly isolated monocytes were added to the hydrogel at a 1:7 ratio of monocytes to tenocytes. 100 µl of the hydrogel cell suspension was added to the bottom channel with 200 µl of X-VIVO 10 media (Lonza, 04-380Q) supplemented with 20 ng/ml M-CSF (PeproTech, 300–25). Bottom components were cultured for 6 days (D-6—D0), and M-CSF media was half-replaced each day. At D-2 the top component was seeded with HUVECs as described above. Briefly, the backside of the membrane was coated with collagen, allowed to crosslink an incubator for 15 min, and then placed on a reservoir filled with EGM-2 media. Fibronectin was added to the flow channel at 5 µg/cm2 and maintained at room temperature for 1 h for coating. HUVECs were seeded in the flow channel at 40,000 cells/cm2 and cultured statically for 24 h. At D-1, both the top and bottom components were removed from the respective reservoirs and combined to form a complete device. Devices were then connected to circulating flow, and HUVECs were shear-primed at 1.5 dynes/cm2. At D0 freshly isolated monocytes were added to the flow circuit at 200,000 cells/ml and 10 ng/ml TGF-β1-supplemented X-VIVO 10 was added to the bottom channel. The culture was maintained for 24 h before confocal imaging. Monocytes were isolated from healthy donors with informed consent before each experiment according to an approved protocol by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board (STUDY0004777). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Cell viability assays

To compare cell viability between in-house produced PDMS flow inserts and manufactured flow inserts, a LIVE/DEAD™ Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit (Invitrogen, L3224) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. HUVECs were cultured in both inserts for 24 h of static culture, and percent viability was quantified in FIJI/ImageJ (NIH, USA). To confirm that the manufactured inserts do not release cytotoxic leachates, an XTT (2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate) Cell Viability Assay (Biotium, 30,007) was performed. Both insert types were placed in either EGM-2 or X-VIVO 10 media and incubated for 24 h. The conditioned media was then added to HUVECs cultured in a 96-well plate. After 24 h of culture, the XTT assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance readings of sample wells were collected at 450 nm and were subtracted by background absorbance at 630 nm.

Phase contrast microscopy studies

To acquire phase contrast time-lapse videos, a Nikon Ti2E inverted microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with a sCMOS camera (Zyla 4.2, Andor, UK) and a 40 × objective was used. To maintain conditions at 37 °C devices were placed in an incubation stage (Okolab, Italy), and media reservoirs were placed in a bead bath. A moistened Kim wipe was placed in the incubation stage for humidity. The fluidic imaging setup is shown in Fig. 4A. The monocyte suspension was added to the inlet reservoir of the flow circuit at 200,000 cells/ml. Devices seeded with HUVECs were placed in the incubation stage and connected to the flow circuit. Flow was then started at a rate of 50 µl/min. Phase contrast images were taken every 8 s for 1 h and processed in FIJI/ImageJ.

Fluorescence microscopy studies

To visualize monocyte transmigration over 24 h, monocytes were live-labeled with DiI. Monocytes were added at a concentration of 200,000 cells/ml to the flow circuit and the flow rate was set to 50 µl/min. For static devices, a rolling infusion of monocytes at 4000 cells/μl was added, resulting in approximately 5000 cells in the channel. MCP-1 (100 ng/ml) was added to the bottom channels of HUVEC-seeded devices. After 24 h of monocyte circulation, confocal z-stack images were acquired with an Andor spinning disk confocal microscope (Andor Technology, United Kingdom) on Fusion software with a 10 × objective and a 1.33 µm step size. Images were processed in Imaris (Oxford Instruments, United Kingdom).

Immunofluorescence staining

For HUVEC staining, flow channels were first washed with PBS. ICAM-1 antibody (BioLegend, 353,102) was diluted 1:100 in EGM-2 media and incubated in the flow channel for 15 min at 37 ℃. After washing with PBS, the channels were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Invitrogen, I28800) for 10 min. Top and bottom channels were washed three times with PBS, and the flow channel was blocked with 5% goat serum (Invitrogen) containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature. The secondary antibody was then diluted 1:200 in blocking solution and added to the flow channel for 1 h at room temperature (see supplementary Table 2 for secondary antibodies). Nuclei were then stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, H3570) diluted 1:10,000 in PBS for 5 min. For VE-cadherin (R&D Systems, MAB8381) and PECAM-1 (Invitrogen, PA5-32,321), antibodies were diluted (1:100) and added after the fixation step. To stain for F-actin, HUVECs were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS after fixation. Phalloidin conjugated antibody (Abcam, ab176753) was diluted 1:1000 in 1% BSA and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Images were acquired with an Andor spinning disk confocal microscope on Fusion software. Images were processed in ImageJ and the same brightness and contrast settings were kept consistent across all images.

Image analysis

For VE-cadherin junctional gap width quantification, 30 measurements were taken in each field of view across three separate devices per condition. For ICAM-1 quantification, an intensity threshold was defined based on the distribution of ICAM-1 signal to determine a high and low ICAM-1 expression cutoff. Cells were segmented in ImageJ to calculate the mean pixel intensity per cell, and the percent of cells within each ICAM-1 expression threshold was plotted out of 100%. To quantify cell alignment, cells were stained with a LIVE/DEAD™ kit as above and fitted with ellipses using the Analyze Particles feature of ImageJ. Angles relative to the flow axis per cell were graphed as radar plots in MATLAB using the CircHist plugin72. Monocyte transmigration from time-lapse phase videos was quantified manually in ImageJ by counting phase-dark and phase-bright monocytes in the final frame. To quantify fluorescently labeled monocytes in confocal images, the Spots tool in Imaris was used to identify cells based on a specified diameter. Cells below the membrane were considered to be transmigrated.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and statistically analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). An unpaired t-test was used to compare differences between two groups and an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used for comparison of multiple groups, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. All quantifiable data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation.

Data availability

All data related to the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wu, F., Nerlich, M. & Docheva, D. Tendon injuries: Basic science and new repair proposals. EFORT Open Rev. 2, 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1302/2058-5241.2.160075 (2017).

Hopkins, C. et al. Critical review on the socio-economic impact of tendinopathy. Asia Pac. J. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rehabil. Technol. 4, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2016.01.002 (2016).

Ellis, I. M., Schnabel, L. V. & Berglund, A. K. Defining the profile: Characterizing cytokines in tendon injury to improve clinical therapy. J. Immunol. Regener. Med. 16, 100059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regen.2022.100059 (2022).

Mehrzad, R. et al. The economic impact of flexor tendon lacerations of the hand in the United States. Ann. Plast. Surg. 83, 419–423 (2019).

Merkel, M. F. R., Hellsten, Y., Magnusson, S. P. & Kjaer, M. Tendon blood flow, angiogenesis, and tendinopathy pathogenesis. Transl. Sports Med. 4, 756–771. https://doi.org/10.1002/tsm2.280 (2021).

Lipman, K., Wang, C., Ting, K., Soo, C. & Zheng, Z. Tendinopathy: injury, repair, and current exploration. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 12, 591–603. https://doi.org/10.2147/dddt.S154660 (2018).

Tempfer, H. & Traweger, A. Tendon vasculature in health and disease. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2015.00330 (2015).

Ajalik, R. E. et al. Human tendon-on-a-chip for modeling the myofibroblast microenvironment in peritendinous fibrosis. Adv. Healthc. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202403116 (2024).

de la Durantaye, M., Piette, A. B., van Rooijen, N. & Frenette, J. Macrophage depletion reduces cell proliferation and extracellular matrix accumulation but increases the ultimate tensile strength of injured Achilles tendons. J. Orthop. Res. 32, 279–285. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.22504 (2014).

Nichols, A. E. C., Best, K. T. & Loiselle, A. E. The cellular basis of fibrotic tendon healing: challenges and opportunities. Transl. Res. 209, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2019.02.002 (2019).

Liu, C., Yu, K., Bai, J., Tian, D. & Liu, G. Experimental study of tendon sheath repair via decellularized amnion to prevent tendon adhesion. PLoS ONE 13, e0205811. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205811 (2018).

Monteiro, R. F. et al. Writing 3D in vitro models of human tendon within a biomimetic fibrillar support platform. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 50598–50611. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c22371 (2023).

Ajalik, R. E. et al. Human organ-on-a-chip microphysiological systems to model musculoskeletal pathologies and accelerate therapeutic discovery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.846230 (2022).

Aird, W. C. Spatial and temporal dynamics of the endothelium. J. Thromb. Haemost. 3, 1392–1406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01328.x (2005).

Koutsiaris, A. G. et al. Volume flow and wall shear stress quantification in the human conjunctival capillaries and post-capillary venules in vivo. Biorheology 44, 375–386 (2007).

Sonmez, U. M., Cheng, Y. W., Watkins, S. C., Roman, B. L. & Davidson, L. A. Endothelial cell polarization and orientation to flow in a novel microfluidic multimodal shear stress generator. Lab Chip 20, 4373–4390. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0lc00738b (2020).

Tambe, R. S. et al. Fluid shear, intercellular stress, and endothelial cell alignment. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00363.2014 (2015).

Khire, T. S. et al. Microvascular mimetics for the study of leukocyte-endothelial interactions. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 13, 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12195-020-00611-6 (2020).

Cucullo, L. et al. A new dynamic in vitro model for the multidimensional study of astrocyte-endothelial cell interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res. 951, 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03167-0 (2002).

Mansouri, M. et al. The modular µSiM reconfigured: Integration of microfluidic capabilities to study in vitro barrier tissue models under flow. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 11, 2200802. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202200802 (2022).

Chistiakov, D. A., Orekhov, A. N. & Bobryshev, Y. V. Effects of shear stress on endothelial cells: go with the flow. Acta Physiol. (Oxford) 219, 382–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12725 (2017).

McCloskey, M. C. et al. The modular µSiM: A mass produced, rapidly assembled, and reconfigurable platform for the study of barrier tissue models in vitro. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 11, 2200804. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202200804 (2022).

Salminen, A. T. et al. Ultrathin dual-scale nano- and microporous membranes for vascular transmigration models. Small 15, 1804111. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201804111 (2019).

Mansouri, M. et al. Transforming static barrier tissue models into dynamic microphysiological systems. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/66090 (2024).

Dejana, E., Corada, M. & Lampugnani, M. G. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions. Faseb J. 9, 910–918 (1995).

Seebach, J. et al. Endothelial barrier function under laminar fluid shear stress. Lab. Investig. 80, 1819–1831. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3780193 (2000).

Noria, S., Cowan, D. B., Gotlieb, A. I. & Langille, B. L. Transient and steady-state effects of shear stress on endothelial cell adherens junctions. Circ. Res. 85, 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.85.6.504 (1999).

Ukropec, J. A., Hollinger, M. K. & Woolkalis, M. J. Regulation of VE-cadherin linkage to the cytoskeleton in endothelial cells exposed to fluid shear stress. Exp. Cell Res. 273, 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1006/excr.2001.5453 (2002).

Muller, W. A., Weigl, S. A., Deng, X. & Phillips, D. M. PECAM-1 is required for transendothelial migration of leukocytes. J. Exp. Med. 178, 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.178.2.449 (1993).

Auerbach, S. D., Yang, L. & Luscinskas, F. W. Adhesion Molecules: Function and Inhibition (Springer, 2007).

Salminen, A. T. et al. Endothelial cell apicobasal polarity coordinates distinct responses to luminally versus abluminally delivered TNF-α in a microvascular mimetic. Integr. Biol. (Cambridge) 12, 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/intbio/zyaa022 (2020).

Yang, L. et al. ICAM-1 regulates neutrophil adhesion and transcellular migration of TNF-alpha-activated vascular endothelium under flow. Blood 106, 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2004-12-4942 (2005).

Nakadate, H., Sekizuka, E., Aomura, S. & Minamitani, H. Combinations of hydrostatic pressure and shear stress time-dependently decrease E-selectin, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cultured endothelial cells. J. Biomech. Sci. Eng. 7, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1299/jbse.7.118 (2012).

Stroka, K. M. & Aranda-Espinoza, H. A biophysical view of the interplay between mechanical forces and signaling pathways during transendothelial cell migration. Febs J. 277, 1145–1158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07545.x (2010).

Weber, K. S. C., von Hundelshausen, P., Clark-Lewis, I., Weber, P. C. & Weber, C. Differential immobilization and hierarchical involvement of chemokines in monocyte arrest and transmigration on inflamed endothelium in shear flow. Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 700–712 (1999).

Bradfield, P. F., Johnson-Léger, C. A., Zimmerli, C. & Imhof, B. A. LPS differentially regulates adhesion and transendothelial migration of human monocytes under static and flow conditions. Int. Immunol. 20, 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxm136 (2007).

Muller, W. A. Leukocyte-endothelial-cell interactions in leukocyte transmigration and the inflammatory response. Trends Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00117-0 (2003).

Mossu, A. et al. A silicon nanomembrane platform for the visualization of immune cell trafficking across the human blood-brain barrier under flow. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39, 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678x18820584 (2019).

Moazzam, F., DeLano, F. A., Zweifach, B. W. & Schmid-Schönbein, G. W. The leukocyte response to fluid stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 5338–5343. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.10.5338 (1997).

Hudig, D., Hunter, K. W., Diamond, W. J. & Redelman, D. Properties of human blood monocytes. II. Monocytes from healthy adults are highly heterogeneous within and among individuals. Cytom. Part B Clin. Cytom. 86, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1002/cyto.b.21141 (2014).

Ahmad, D., Linares, I., Pietropaoli, A., Waugh, R. E. & McGrath, J. L. Sided stimulation of endothelial cells modulates neutrophil trafficking in an in vitro sepsis model. Adv. Healthc. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202304338 (2024).

Ahmad, S. D., Cetin, M., Waugh, R. E. & McGrath, J. L. A computer vision approach for analyzing label free leukocyte trafficking dynamics on a microvascular mimetic. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1140395 (2023).

León, B. & Ardavín, C. Monocyte migration to inflamed skin and lymph nodes is differentially controlled by L-selectin and PSGL-1. Blood 111, 3126–3130. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-07-100610 (2008).

Chappell, D. C., Varner, S. E., Nerem, R. M., Medford, R. M. & Alexander, R. W. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates adhesion molecule expression in cultured human endothelium. Circ. Res. 82, 532–539. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.82.5.532 (1998).

Hattori, K. et al. Microfluidic perfusion culture chip providing different strengths of shear stress for analysis of vascular endothelial function. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 118, 327–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.02.006 (2014).

Soldati, S. et al. High levels of endothelial ICAM-1 prohibit natalizumab mediated abrogation of CD4+ T cell arrest on the inflamed BBB under flow in vitro. J. Neuroinflammation 20(1), 123 (2023).

McCloskey, M. C. et al. Pericytes enrich the basement membrane and reduce neutrophil transmigration in an in vitro model of peripheral inflammation at the blood brain barrier. Biomater. Res. 28, 0081 (2024).

Bienvenu, K. & Granger, D. N. Molecular determinants of shear rate-dependent leukocyte adhesion in postcapillary venules. Am. J. Physiol.Heart Circ. Physiol. 264, H1504–H1508. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.5.H1504 (1993).

Chiu, J. J. et al. Shear stress increases ICAM-1 and decreases VCAM-1 and E-selectin expressions induced by tumor necrosis factor-[alpha] in endothelial cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 73–79. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.Atv.0000106321.63667.24 (2004).

Muscat, S., Nichols, A. E. C., Gira, E. & Loiselle, A. E. CCR2 is expressed by tendon resident macrophage and T cells, while CCR2 deficiency impairs tendon healing via blunted involvement of tendon-resident and circulating monocytes/macrophages. Faseb J. 36, e22607. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.202201162R (2022).

Zeng, Y. & Tarbell, J. M. The adaptive remodeling of endothelial glycocalyx in response to fluid shear stress. PLoS ONE 9, e86249. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086249 (2014).

Hardy, L., Booth, T., Lau, E., Handel, T. & Kirby, J. Examination of MCP-1 (CCL2) partitioning and presentation during transendothelial leukocyte migration. Lab. Investing. J. Tech. Methods Pathol. 84, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.labinvest.3700007 (2004).

Ghousifam, N., Eftekharjoo, M., Derakhshan, T. & Gappa-Fahlenkamp, H. Effects of local concentration gradients of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) on monocytes adhesion and transendothelial migration in a three-dimensional (3D) in vitro vascular tissue model. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1903.05144 (2019).

Wang, X.-L. et al. The role of PSGL-1 in pathogenesis of systemic inflammatory response and coagulopathy in endotoxemic mice. Thromb. Res. 182, 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2019.08.019 (2019).

Gschwandtner, M., Derler, R. & Midwood, K. S. More than just attractive: How CCL2 influences myeloid cell behavior beyond chemotaxis. Front. Immunol. 10, 2759. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02759 (2019).

Jiang, Y., Beller, D. I., Frendl, G. & Graves, D. T. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulates adhesion molecule expression and cytokine production in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 148, 2423–2428 (1992).

Roca, H. et al. CCL2 and interleukin-6 promote survival of human CD11b+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells and induce M2-type macrophage polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34342–34354. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.042671 (2009).

Montgomery, A. et al. Overlapping and distinct biological effects of IL-6 classic and trans-signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol.Cell Physiol. 320, C554–C565. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00323.2020 (2021).

Marlin, S. D. & Rothlein, R. Encyclopedia of Immunology 2nd edn. (Elsevier, 1998).

Maus, U. et al. Role of endothelial MCP-1 in monocyte adhesion to inflamed human endothelium under physiological flow. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 283, H2584-2591. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2002 (2002).

Gomez-Florit, M., Labrador-Rached, C. J., Domingues, R. M. A. & Gomes, M. E. The tendon microenvironment: Engineered in vitro models to study cellular crosstalk. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 185, 114299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2022.114299 (2022).

Wang, Y., Lu, X., Lu, J., Hernigou, P. & Jin, F. The role of macrophage polarization in tendon healing and therapeutic strategies: Insights from animal models. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2024.1366398 (2024).

Slack, R. J., Macdonald, S. J. F., Roper, J. A., Jenkins, R. G. & Hatley, R. J. D. Emerging therapeutic opportunities for integrin inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41573-021-00284-4 (2022).

Song, X., Jiang, C., Yu, M., Lu, C. & He, X. CCR2/CCR5 antagonist cenicriviroc reduces colonic inflammation and fibrosis in experimental colitis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 39, 1597–1605. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.16622 (2024).

Chiu, J.-J. & Chien, S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: Pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol. Rev. 91, 327–387. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00047.2009 (2011).

DePaola, N., Gimbrone, M. A. Jr., Davies, P. F. & Dewey, C. F. Jr. Vascular endothelium responds to fluid shear stress gradients. Arterioscler. Thromb. 12, 1254–1257. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.atv.12.11.1254 (1992).