Abstract

Background: Persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) belongs to the Ebenaceae family, which includes six genera and about 400 species. This study evaluated the genetic diversity of 100 persimmon accessions from Hatay province, Türkiye using 42 morphological and pomological traits, along with inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers and multivariate analysis. Results: Statistical analysis revealed significant differences among the accessions (ANOVA, p < 0.05). The coefficient of variation ranged from 19.24% for leaf length to 133.89% for fruit calyx groove end, with 97.62% of traits showing more than 20% variation. This indicates high genetic variability. Fruit weight, length, and diameter varied greatly, with strong positive correlations between fruit weight and other traits. Principal component analysis explained 72.42% of the total variance, while cluster analysis showed varying levels of similarity among accessions. ISSR analysis identified 139 bands, 128 of which were polymorphic. The similarity index ranged from 0.41 to 0.96. Notably, accessions ‘P78’, ‘P7’, ‘P48’, ‘P29’, ‘P44’, ‘P25’, ‘P5’, ‘P98’, ‘P80’, ‘P50’, ‘P37’, ‘P77’, ‘P57’, ‘P56’, ‘P41’, ‘P73’, ‘P39’, ‘P65’, ‘P72’, and ‘P61’ were identified as promising candidates for further study. Conclusions: This study demonstrates significant genetic diversity in persimmon accessions from Hatay. The high variability supports adaptability and resilience. Positive correlations among traits, especially fruit weight, are useful for breeding. ISSR markers highlighted valuable polymorphic bands, underlining the importance of local germplasm for developing resilient cultivars. Variations in growth vigor and ripening dates offer opportunities for customized cultivation practices, contributing to sustainable agriculture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) is a member of the Ebenaceae family, which encompasses six genera and about 400 species1. Within the Diospyros genus, there are around 200 species, yet only four of them hold significant pomological value. D. kaki is among these four and stands out as the most commercially important species cultivated. The fundamental chromosome number for D. kaki is 15; however, the grown cultivars exhibit variations with diploid (2n = 2x = 30), tetraploid (4x = 60), or hexaploid (6x = 90) configurations. This chromosomal diversity indicates that many cultivars of D. kaki are either tetraploid or hexaploid. In addition, D. kaki is commonly known as the Japanese persimmon or oriental persimmon, highlighting its cultural significance and geographical distribution2. Persimmon is a deciduous fruit crop that thrives in subtropical climates and is primarily cultivated in subtropical and temperate regions worldwide. Originally from China, persimmon has seen the most cultivation and production in Japan3. While the precise date of its introduction to Anatolia remains unclear, historical records suggest it has been present for a considerable time4. The fruit made its way to Türkiye from Russia via the Black Sea region, and it is believed that both D. kaki and its relative, D. lotus L., originated from the same area. Local genotypes, in particular, demonstrate a wide range of adaptability to various agro-climatic conditions, making them a crucial asset for breeding programs. Therefore, it is vital to conserve the valuable genetic resources inherent in these local genotypes for their effective use5. To ensure that these resources are preserved, it is crucial to conduct thorough assessments of the genetic variability found among local accessions6. By evaluating this variability, researchers can identify key traits that contribute to resistance and adaptability, facilitating the development of improved cultivars. This process not only supports agricultural innovation but also helps maintain biodiversity and the integrity of local ecosystems. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of genetic variability is essential for leveraging these local genotypes in sustainable agricultural practices7. Selections made from local populations are defined based on various morphological characteristics, primarily including traits such as size, thickness, and flavor. However, these morphological traits can be influenced by environmental conditions and yield stress factors. For instance, climate changes or stress conditions, to which plants are exposed, can alter the characteristics of individuals. This situation can complicate the achievement of reliable results in the identification of these individuals. Therefore, it is important to employ more comprehensive assessment methods in the selection of local populations8. Molecular marker techniques are widely used for the identification of persimmon cultivars, clones, and accessions. Techniques such as RAPD9, AFLP10, SRAP11, SSR12,13,14, IRAP15, SCoT8,16,17, and ISSR8,15 are commonly employed for this purpose. Recently, inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers have gained popularity in distinguishing various persimmon cultivars, clones, and accessions, as well as in assessing genetic relationships and diversity. These markers are essential for the conservation, utilization, and management of genetic resources18. Furthermore, ISSR markers reveal valuable polymorphisms that indicate genetic distances between local germplasm and different cultivars, contributing to the preservation of local genetic diversity within gene banks19. The ISSR technique, which is based on PCR, amplifies DNA segments found between two identical microsatellite repeat regions20. These ISSR fragments are usually inherited as dominant markers, demonstrating high reproducibility, and can be effectively visualized on agarose gels21. There is a need for studies that combine morphological, pomological, and molecular markers for the identification, conservation, and sustainability of plant genetic diversity. Such research allows for better management of genetic resources and the development of conservation strategies. Additionally, preserving plant diversity contributes to enhancing agricultural productivity and maintaining ecosystem balance.

To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study in Türkiye utilizing morphological, pomological, and ISSR primers across such a large number of accessions. This research aims to make a significant contribution to the literature by providing new insights into the conservation and sustainable management of local genetic resources. Additionally, it will offer researchers a comprehensive approach to genetic diversity analysis, helping them develop strategies for creating more resilient varieties under varying climate and agro-environmental conditions. From a sectoral perspective, such studies lay a critical foundation for enhancing agricultural productivity and obtaining crops that are more resistant to climate change. A better understanding of local genotypes will enable farmers to optimize their production strategies, thereby increasing their economic gains. Ultimately, this research promises to create a wide-reaching impact in both academic and applied fields.

To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study in Türkiye utilizing morphological, pomological, and ISSR primers across such a large number of accessions. This research aims to make a significant contribution to the literature by providing new insights into the conservation and sustainable management of local genetic resources. Additionally, it will offer researchers a comprehensive approach to genetic diversity analysis, helping them develop strategies for creating more resilient varieties under varying climate and agro-environmental conditions. From a sectoral perspective, such studies lay a critical foundation for enhancing agricultural productivity and obtaining crops that are more resistant to climate change. A better understanding of local genotypes will enable farmers to optimize their production strategies, thereby increasing their economic gains. Ultimately, this research promises to create a wide-reaching impact in both academic and applied fields.

Materials and methods

Plant material

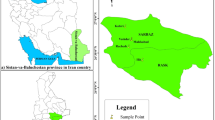

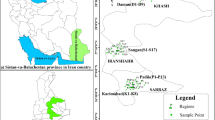

In this study, the genetic diversity of 100 accessions of persimmon (D. kaki) naturally growing in Hatay, located in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of Türkiye, was investigated using morphological, pomological, and ISSR markers. The location information of each accession was recorded using a GPS device. To prevent the sampling and collection of clones from the selected accessions, a distance of 200 m was maintained between each accession. Hatay is located between 36°15’48"N latitude and 36°08’02"E longitude, with an elevation of 100 m above sea level (Fig. 1). The soil types in the central districts (Antakya and Defne) consist of fertile alluvial soils suitable for agriculture, as well as calcareous and rocky soils found in the mountainous areas. The formal identification of the samples was performed by Dr. Yazgan Tunç.

The characteristics evaluated

To determine the phenotypic diversity of the selected accessions, a total of 42 morphological and pomological traits were used. For this purpose, 30 adult leaves and fruits were randomly selected and harvested during the harvesting stage. A digital caliper brand Insize with a precision of 0.01 mm was used to measure leaf length and width, petiole length and width, fruit length and diameter, and fruit stalk length and thickness. A digital scale brand Swock (model no. JD602) with a precision of 0.01 g was used to determine the weights of fruits and seeds. Fruit firmness was determined using a penetrometer (PCE brand, model no. FM-200), measured in kg force per cm (kgf cm-1). Qualitative traits were graded and coded according to the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants21, which has also been used in previous studies22,23,24,25,26.

Molecular analysis through inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) markers

DNA extraction from young persimmon leaves was performed using the CTAB method27. DNA concentrations were assessed with a spectrophotometer (ONDA VIS-10 plus), and the DNAs were visualized on a 2% agarose gel via gel electrophoresis alongside a DNA ladder (100 bp). The extracted DNAs were stored at − 20 °C. For ISSR analysis, 17 different primers were tested, resulting in band formation with 10 of them. The PCR reactions included 2 µL DNA (20 ng), 1.5 µL of 10×PCR buffer, 0.2 µL of Taq DNA polymerase (5 u/µL), 1 µL of dNTP (2.5 mM), 1.5 µL of MgCl2 (25 mM), 2 µL of 10 mM ISSR primer, and 6.8 µL of H2O, resulting in a final volume of 15 µL for the PCR products. The PCR cycling conditions were performed according to Uzun et al.28: an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 38 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 50 °C for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 1.15 min, and a final extension cycle at 72 °C for 7 min.

Statistical analysis

In this research carried out in 2022 and 2023, the average of datasets from both years was utilized. The variance homogeneity was tested using Fisher test and the data normality was checked using Shapiro-Wilk test. Multivariate analysis techniques were performed on data mean values to assess genetic similarities and differences within persimmon germplasm. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with the JMP® Pro 1729 statistical software to detect significant differences among the 100 accessions. The same software was also employed to determine the minimum, maximum, mean, and coefficient of variation (CV) for the datasets. Various multivariate analysis techniques, including correlations, principal component analysis, and UPGMA-based clustering analysis, were conducted using the Origin Pro® 2024b30 statistical software package. For correlation analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated for each pair of variables. A two-dimensional scatter plot based on principal components was generated to enhance the visualization of sample distribution. To minimize potential errors caused by scale differences, the mean for each variable was calculated and normalized using Z-scores before the clustering analysis. The Ward method, utilizing Euclidean distance, was applied for the clustering analysis31. To validate cluster stability, the bootstrapping method was used as a resampling technique to enhance the reliability of the groups in the dendrogram and ensure the robustness of the results.

In ISSR analyses, images obtained by agarose gel electrophoresis and imaging (Kodak) were scored as the presence of a band (1), its absence (0), and no amplification (9). The data were analyzed using NTSYS (version 2.11X) software32. Dendrograms for the accessions were created based on a similarity matrix employing the Dice method and unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean (UPGMA) clustering analysis33. Furthermore, the total number of bands, the number of polymorphic bands, and the polymorphism rate were detected for each marker. The polymorphism rate was calculated using the formula presented in Eq. (1)34.

In our study, specific ISSR markers were selected to determine the genetic diversity in naturally occurring persimmon accessions. The selected markers possess characteristics that reflect genetic diversity, with high polymorphism and strong reproducibility. ISSR markers are suitable for analyzing genetic variation due to their ability to reliably detect inter- and intra-species genetic diversity.

The unique aspect of this research is that, although it was conducted in a single ecological region, it investigates the relationship between environmental variables and genetic diversity. This method has become more suitable for analyzing the genetic diversity of the region more specifically and accurately.

The procedure has been optimized to better observe the effects of environmental factors. The amplification process of the ISSR markers used in genetic analyses has been simplified, and time costs have been minimized. Additionally, thanks to bioinformatics analyses, the data processing has been carried out quickly and effectively. This simplified procedure has made the process of analyzing the genetic diversity of naturally occurring persimmon accessions in a single ecological region more efficient.

Results and discussion

Descriptive statistics, morphological, and pomological diversity among the accessions

Statistical descriptive parameters related to the morphological and pomological traits used to examine D. kaki accessions are presented in detail in Table 1. The examined accessions showed statistically significant differences according to the morphological and pomological datasets (ANOVA, p < 0.05). Within the obtained findings, the coefficient of variation varied between leaf length (19.24%) and fruit calyx groove end (133.89%). Additionally, 41 out of 42 characters (97.62%) had a CV greater than 20.00%. This indicates a high level of diversity among the accessions35. This situation indicates that the studied germplasm exhibits a high level of heterozygosity and that open pollination has resulted in genetic variability among the accessions in the investigated area36. Traits with high coefficients of variation (CV) offer a wide range of features, thereby providing more opportunities for selection based on those traits37.

Leaf length ranged from 61.32 (‘P39’) to 130.18 mm (‘P43’), leaf width from 30.24 (‘P 22) to 79.47 mm (‘P70’), petiole length from 8.03 (‘P31’) to 16.53 mm (‘P73’), and petiole width from 2.01 (‘P93’) to 4.95 mm (‘P65’). In a study conducted in Türkiye, leaf length varied between 69.8 and 137.8 mm, while leaf width ranged from 31.5 to 86.5 mm26. A study conducted in China reported petiole length ranging from 8 to 14 mm24. The reported leaf length and width demonstrate a substantial range, indicating significant variability among the accessions. The findings are consistent with existing literature, as evidenced by the comparative analysis with Yilmaz et al.26 and Li et al.24. The variation in leaf dimensions could suggest adaptation to diverse environmental conditions, which may have implications for photosynthetic efficiency and overall plant health. Fruit weight, fruit length, and fruit diameter ranged from 1.55 (‘P38’) to 79.00 g (‘P65’), 11.16 (‘P62’) to 46.88 mm (‘P44’), and 12.54 (‘P33’) to 60.95 mm (‘P7’), respectively. In a similar study conducted in Ukraine, fruit weight varied between 2.30 and 81.30 g, while fruit length ranged from 8.84 to 79.73 mm22. Fruit diameter in Iran ranged from 11.5 to 77.80 mm23, whereas in Ukraine it varied between 12.84 and 55.34 mm22. Our findings are consistent with those reported by other researchers. The extensive range in fruit weight (1.55 to 79.00 g), length (11.16 to 46.88 mm), and diameter (12.54 to 60.95 mm) suggest a wide genetic variability among the accessions, which can be critical for breeding programs aimed at improving fruit quality. The alignment of these results with those obtained from studies conducted in Ukraine and Iran highlights the potential for selecting superior accessions based on fruit characteristics for cultivation. Fruit calyx size ranged from 2.02 (‘P25’) to 6.98 mm (‘P21’). Khademi et al.23 reported this value to be between 2.16 and 7.00 mm. Our findings are compatible with theirs. Fruit stalk length varied from 3.20 (‘P84’) to 12.97 mm (‘P78’), and fruit stalk thickness ranged from 1.30 (‘P73’) to 4.32 mm (‘P6’). In a study conducted in Türkiye, these values were detected to range from 3.50 to 14.55 mm and 1.70 to 4.71 mm, respectively26. The fruit calyx size and stalk dimensions contribute to a better understanding of the morphology of these accessions. The compatibility of these findings with those reported by Khademi et al.23 and Yilmaz et al.26 regarding fruit stalk length and thickness indicates consistency in measurements across different geographical regions. The variability in stalk dimensions could significantly impact fruit handling and storage, which are essential considerations in post-harvest management. Seed weight varied from 0.15 (‘P19’) to 1.35 g (‘P21’), seed length from 6.12 (‘P92’) to 16.90 mm (‘P8’), and seed width from 1.08 (‘P61’) to 33.24 mm (‘P83’). Seed weight was reported to range from 0.1 to 1.0 g in Ukraine22, from 0.00 to 1.33 g in Türkiye26, and from 0.00 to 1.45 g in Iran23. Seed length ranged from 8.30 to 20.88 mm according to Grygorieva et al.22 and from 0.0 to 3.2 mm as determined by Khademi et al.23. Grygorieva et al.22 reported that seed width varied between 1.98 and 7.09 mm. The data are consistent with previous studies. The variation observed in seed weight, length, and width reflects the diversity within the germplasm. The number of seeds ranged from 1 (‘P21’, ‘P23’, ‘P48’, ‘P51’, ‘P53’, ‘P76’, ‘P80’, ‘P87’, ‘P89’, ‘P96’, and ‘P100’) to 8 (‘P13’, ‘P18’, ‘P32’, ‘P34’, ‘P35’, ‘P77’, ‘P83’, and ‘P93’). Similar results were obtained in studies conducted in Ukraine22 and Türkiye26. Fruit firmness was detected to be between 3.12 (‘P80’) and 12.76 kgf cm-2 (‘P89’). In a study conducted in Iran, this value was found to range from 1.16 to 11.14 kgf cm-223. Our findings are consistent with previous research. Firmness is particularly crucial as it relates to post-harvest handling and marketability, making this data valuable for both agricultural practices and commercial applications.

Overall, the results elucidate the genetic variability present within the studied accessions, which is vital for future research and breeding programs. This comprehensive analysis provides a robust foundation for understanding the phenotypic characteristics of the species and highlights the potential for further studies aimed at enhancing fruit quality and yield in agricultural settings. The consistent patterns observed across different studies lend credibility to the findings and suggest that these traits are fundamental to the species’ adaptability and commercial value.

The distribution of frequency for the qualitative morphological traits measured in the examined D. kaki accessions is provided in detail in Table 2. The classification of tree growth vigor into weak (26 accessions), medium (24 accessions), and strong (50 accessions) categories highlights the diversity among the accessions studied. With 50 accessions exhibiting strong vigor, it suggests that a significant portion of the population is well-adapted for optimal growth, which could be beneficial for cultivation and breeding programs. This finding aligns with Li et al.24, who noted a similar predominance of strong vigor in their research. This consistency in the findings emphasizes the importance of selecting strong growth traits in D. kaki accessions. Particularly in agricultural settings, considering that growth vigor can significantly impact fruit yield and quality, the significance of these selections increases. Overall, understanding the distribution of growth vigor can inform future research and management practices, guiding efforts to enhance the productivity and resilience of these accessions in various environments. In terms of other significant morphological parameters, the predominant characteristics observed were as follows: tree growth habit was drooping (30 accessions), shoot length (1-year-old) was medium (43 accessions), shoot thickness (1-year-old) was thick (47 accessions), shoot color (1-year-old, sunny side) was brown (46 accessions), the tendency for side branching was high (56 accessions), trunk surface structure was rough (44 accessions), leaf shape was ovate (36 accessions), leaf base shape was broad acute (33 accessions), and leaf apex shape was acute (46 accessions). These findings highlight the morphological diversity and adaptability of D. kaki accessions. For instance, the prevalence of the “Drooping” growth habit may indicate the accessions’ ability to adapt flexibly to environmental conditions. This trait can be desirable for fruit production, as drooping tree structures often facilitate better light exposure for the fruits. The dominance of medium-length and thickness shoots over one year suggests that the trees exhibit healthy growth. The brown color of the shoots may influence the plant’s photosynthetic efficiency, depending on light conditions. A high tendency for lateral branching is a positive aspect, as it could enhance the plant’s expansion and increase fruit yield. Additionally, the “Rough” trunk surface structure may improve the accessions’ resistance to diseases and pests. The “Ovate” leaf shape, along with the “Broad acute” leaf base and “Acute” leaf apex, indicates the potential of these plants to utilize water and nutrients more effectively. This shows that these accessions are promising for agricultural production. Ripening date was categorized as Mid-September (35 accessions), Late September (45 accessions), and Mid-October (20 accessions). The categorization of ripening dates among the accessions indicates a range of maturity times, which can be advantageous for staggered harvesting and market supply. This diversity in ripening periods can also aid in breeding programs aimed at developing cultivars with desired harvest times, enhancing adaptability to different climates and consumer preferences38. Fruit shape varied between narrow elliptic and very broadly ovate, with oblate being dominant among 27 accessions. In cross-section, 35 accessions were circular, 35 were irregularly rounded, and 30 were square. The fruit shape of the apex in longitudinal section was truncate (34 accessions), fruit grooving at the apex was moderate (38 accessions), and fruit concentric cracking around the apex was absent or weak (49 accessions). Both fruit concentric cracking around the apex and fruit cracking of the apex were absent or weak (49 and 43 accessions, respectively). The fruit calyx attachment was slightly depressed (43 accessions), and the fruit calyx groove end was absent (90 accessions). The calyx size compared with fruit diameter was large (47 accessions), and the fruit calyx attitude was semi-erect (51 accessions) was dominant.

The fruit color of the skin was identified as follows: green-yellow (17 accessions), yellow-orange (28 accessions), orange (33 accessions), and red-orange (22 accessions). These findings indicate a wide range of fruit skin colors among the studied D. kaki accessions. The most common color is “orange,” with 33 accessions, suggesting that these accessions may be the most commercially preferred. The “yellow-orange” (28 accessions) and “red-orange” (22 accessions) colors also present significant variation, while “green-yellow” (17 accessions) is the least prevalent. Fruit color is an important commercial factor that can significantly influence consumer preferences; thus, this diversity should be taken into account for both marketing and breeding strategies. Additionally, it is worth noting that fruit color may be related to other characteristics such as ripeness, taste, and nutritional value. This variation offers an opportunity for making better selections in agricultural practices and enhances the potential to respond to different market demands. The fruit color of the flesh was determined as follows: yellow (13 accessions), orange-yellow (15 accessions), orange (14 accessions), red-orange (44 accessions), brown-orange (7 accessions), and brown (7 accessions). The results indicate a diversity of flesh color among the studied D. kaki accessions. The dominance of red-orange flesh (44 accessions) suggests that this color may be a desirable trait, likely linked to taste and consumer preferences. Additionally, the presence of other colors such as orange-yellow and orange provides variability that could be advantageous for breeding programs aimed at enhancing fruit quality and market appeal. The occurrence of less common colors like brown and brown-orange (each with 7 accessions) may reflect specific adaptations or genetic traits among certain accessions. This diversity in flesh color also suggests potential correlations with beneficial compound levels, as different pigments are often associated with nutritional quality. Overall, the findings highlight the importance of genetic diversity among these accessions and illustrate how this variability can be leveraged for agricultural improvement and consumer satisfaction. Fruit skin structure was classified into three groups: very bright (26 accessions), bright (55 accessions), and matte (19 accessions). The classification of fruit skin structure into very bright, bright, and matte categories indicates a diversity in the surface characteristics of the accessions. The predominance of bright skin (55 accessions) suggests a potential for appealing aesthetics, which could influence consumer preferences. Brightly colored fruits are often associated with freshness and quality, potentially enhancing their marketability. In contrast, the presence of matte skin (19 accessions) may indicate adaptations to specific environmental conditions or could be a result of genetic factors. Understanding these variations is crucial for breeding programs aimed at optimizing both the visual appeal and quality of the fruit. The classification of fruit astringency into astringent (75 accessions) and non-astringent (25 accessions) provides significant insights into the phenotypic diversity within the studied accessions. Astringency is a crucial sensory attribute that can influence consumer acceptance and marketability. The predominance of astringent accessions suggests a potential challenge for immediate consumption, as these fruits are often less appealing to consumers due to their mouthfeel and taste. Conversely, the presence of non-astringent accessions is noteworthy, as they may offer desirable traits for fresh consumption markets. This diversity presents opportunities for breeding programs aimed at enhancing fruit quality. The identification of non-astringent accessions could be particularly valuable in developing cultivars that meet consumer preferences and market demands, potentially expanding the market reach of D. kaki. Moreover, understanding the genetic and environmental factors contributing to astringency levels may provide pathways for further research, leading to improved cultivation practices and selection criteria. Overall, these findings emphasize the importance of astringency in fruit quality assessment and highlight the potential for breeding strategies to enhance the appeal and profitability of D. kaki in various markets. The seed shape in lateral view was predominantly broad ovate (31 accessions), and the seed color was mainly medium brown (49 accessions).

These findings provide significant insights into the breeding of D. kaki accessions, consumer preferences, and related research. The morphological and pomological diversity presents a great potential for breeding programs, while the presence of strong growth traits and varying ripening dates allows for the development of new cultivars suited to different climatic conditions and market demands. Specifically, the existence of astringent and non-astringent fruit types offers opportunities for creating new fruit accessions tailored to diverse consumption purposes. From a consumer perspective, the variety in fruit colors and flesh colors are important factors influencing preferences, with red-orange flesh being highlighted as a desirable trait linked to taste and consumer appeal. For researchers, these findings provide an opportunity to gain further insights into the genetic diversity of D. kaki. The levels of astringency and differences in fruit structure offer possibilities for in-depth studies on plant physiology and adaptations. Overall, these results serve as a foundational resource for making strategic decisions in both agricultural production and marketing. Our findings generally align with those of Yilmaz et al.26 and Khademi et al.23. The observed differences are thought to be due to the differences in the accessions constituting the study material and the ecological structure of the studied regions. As seen, due to the limited resources in the existing literature, these findings have also been addressed independently from one another, emphasizing the unique characteristics of each trait. This approach creates a rich discussion environment and opens the door to the development of new perspectives in the field of research. The variations in the examined D. kaki accessions are shown in Fig. 2.

Correlations among variables (CMA)

Correlation matrix analysis (CMA) is a statistical method used to assess relationships between two or more variables. Presented in matrix format, it determines the strength and direction of these relationships using Pearson correlation coefficients, which range from − 1 to 1. A value of 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, -1 is a perfect negative correlation, and 0 signifies no relationship. The diagonal values are always 1, reflecting each variable’s perfect relationship with itself. This analysis aids in understanding the nature of variable relationships and enhances the comprehension of complex data. However, accurate interpretation requires careful application and support from additional statistical methods39. Correlation analysis primarily focuses on quantitative characteristics for several reasons. Quantitative data is more suited for statistical analysis due to its numerical nature, allowing for clear identification of linear relationships. Analyses with quantitative data offer greater statistical power, improving result reliability and enabling precise inferences. Additionally, the continuous nature of quantitative data provides more opportunities for analysis and comparison, unlike qualitative data, which is often categorical and less effective for identifying relationships40. Therefore, as in many studies41,42,43, correlation analysis in this study was performed between quantitative data sets. The basic correlations between quantitative morphological variables analyzed in D. kaki accessions are given in Table 3. The findings indicate a complex network of relationships among various morphological traits of the studied accessions, revealing significant correlations that provide insights into their physiological interactions. The positive correlation between leaf width and leaf length (r = 0.263*) suggests a potential link in their growth patterns, which may imply that as one dimension increases, the other does as well, reflecting overall leaf development strategies. Notably, fruit weight exhibited strong positive correlations with multiple attributes, including fruit length (r = 0.399**), fruit diameter (r = 0.410**), fruit stalk thickness (r = 0.546**), seed weight (r = 0.509*), number of seeds (r = 0.379*), and fruit firmness (r = 0.758**). This cluster of relationships emphasizes the interconnectedness of fruit traits, suggesting that heavier fruits tend to be longer, thicker, and firmer, while also carrying more seeds. Such findings are critical for breeding programs focused on enhancing fruit quality and yield, as they identify key traits that can be targeted simultaneously. The observed negative correlations between fruit weight and both fruit stalk length (r= 0.385**) and seed width (r = 0.431**) suggest that increases in these dimensions may not correspondingly enhance fruit weight. This indicates a potential need for balance in fruit development, as increases in stalk length and seed width do not necessarily lead to proportional increases in fruit weight. The strong positive correlations found between fruit length and seed weight (r = 0.818**), seed width (r = 0.616**), and fruit firmness (r = 1.00**) further affirm that fruit dimensions play a significant role in determining seed characteristics, which may have implications for seed viability and overall reproductive success. Conversely, the negative correlations between fruit length and the number of seeds (r=-0.521**) and seed length (r=-0.307*) might suggest that larger fruits do not necessarily produce more seeds, which could reflect ecological adaptations or competitive strategies. The relationships involving fruit diameter and firmness (r = 0.269*) and the negative correlation with fruit calyx size (r=-0.690**) highlight the complexities in fruit morphology that can influence consumer perceptions and marketability. The significant positive correlation between fruit stalk length and thickness (r = 0.752**) suggests that structural integrity in fruit attachment is a critical factor in fruit quality. Finally, the relationships among seed characteristics, particularly the negative correlation observed between seed length and number of seeds (r = 0.999**) and fruit firmness (r = 0.493**), require further investigation. The continuous positive correlations between seed width and number of seeds (r = 0.631**), as well as fruit firmness (r = 0.424**), further underscore the significance of these traits in shaping fruit and seed development. In summary, these correlations provide a valuable framework for understanding the morphological dynamics at play in the studied accessions, and they underscore the need for integrated approaches in breeding strategies that consider multiple traits simultaneously to optimize both fruit quality and yield. The findings obtained from the correlation analysis generally align with the results of Khademi et al.23, although some small differences have emerged. It is believed that these differences stem from the diversity of the ecological conditions associated with the accessions studied. Variations in climate, soil composition, and environmental factors can influence the morphological and physiological characteristics of each accession, leading to specific deviations in the correlation results. Therefore, these differences reflect the interplay between the distinct characteristics of the accessions and the ecological factors at play. Due to the limited number of studies of this nature, the obtained findings have also been discussed independently among themselves. This approach helps us better understand the unique characteristics of each trait while holding the potential to fill gaps in the existing literature. In particular, understanding how these relationships interact allows us to develop a more comprehensive and in-depth perspective. This situation paves the way for future research and encourages similar studies. Therefore, the independent discussion of these findings will make significant contributions to the development of the field.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a statistical technique used to analyze and visualize high-dimensional data sets by reducing complexity. It transforms high-dimensional variables into a lower-dimensional space through new variables called “principal components,” which capture the largest variance in the data. The first principal component accounts for the highest variance, with subsequent components explaining progressively lower variances. PCA helps reveal data structures, making them more interpretable. Additionally, PCA involves extracting eigenvalues greater than one to identify significant components, as these indicate that a component accounts for more variance than a single original variable. By focusing on these components, researchers can reduce dimensionality while retaining essential information, facilitating clearer analyses44. In the PCA framework, eigenvectors with a degree of significance of ≥ 0.23 were identified for each variable (bold values), while the first 19 components, with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0, collectively explained 72.42% of the total variance (Table 4). PC1 explains 5.49% of the total variance, with the greatest contributions coming from fruit shape (0.28), seed color (0.27), fruit firmness (0.25), shoot length (1-year-old) (0.23), and tendency of side branching (0.23). PC2 accounts for 5.32% of the total variance, with the highest contributions made by leaf base shape (0.32), calyx size compared with fruit diameter (0.26), fruit shape of apex in longitudinal Sect. (0.26), shoot color (1-year-old, sunny side) (0.23), and petiole length (mm) (0.23). PC3, which is contributed to most by leaf width (0.34), fruit stalk length (0.34), fruit stalk thickness (0.27), fruit length (0.24), shoot thickness (1-year-old) (0.24), lead shape (-0.24), fruit calyx attachment (-0.24), and petiole width (-0.28), explains 5.12% of the total variation. This distribution indicated a high level of diversity among the germplasms37. The findings revealed significant morphological variation, which points to considerable genetic diversity among the accessions, highlighting the importance of assessing various morphological traits for effective characterization. The aforementioned traits were the most impactful in differentiating and identifying the accessions studied. PC1, PC2, and PC3 were separated according to statistical significance levels and were determined as **p < = 0.01, *p < = 0.05, and **p < = 0.01, respectively.

The PCA scatter plot is a type of graph used to visualize the results of principal component analysis (PCA). This graph displays data points on two or more axes that represent the most important components, effectively reducing the dimensionality of the data. Each point represents a sample in the dataset, while the axes reflect the variability and structure of the data. The PCA scatter plot is useful for understanding the overall distribution of the dataset, identifying groups, and examining relationships, making the processes of data analysis and interpretation more straightforward. Typically, such graphs illustrate how samples with similar characteristics cluster together and how different groups are separated45. The scatter plot of 100 accessions in the 2D principal component analysis is presented in Fig. 3. Accordingly, PC1 (5.49%) and PC2 (5.32%) represent 10.81% of the total variation. The accessions are distributed in four regions of the distribution graph. While 95 accessions are located inside the 95% confidence ellipse, the accessions numbered ‘P13’, ‘P14’, ‘P65’, ‘P76’, and ‘P83’ are located outside this area. Firstly, these accessions may possess distinct characteristics that set them apart from the general population, allowing them to be defined as outliers. Outliers can indicate an unusual condition of morphological or genetic traits. Furthermore, the accessions that fall outside the expected range can be viewed as indicators of high genetic diversity, which may enhance the genetic material’s ability to respond to various adaptations or environmental conditions. These accessions might have adapted better to specific ecological conditions, suggesting they likely developed in different habitats or climatic circumstances. Additionally, the accessions located outside should be considered as cases requiring more in-depth examination and analysis. Gaining further insight into their characteristics is critical for understanding their potential value or risks. Finally, these accessions may offer opportunities for the exploration of new and different traits, which could lead to innovative potentials, particularly in agricultural or commercial contexts. Thus, this situation provides researchers with the opportunity to gather more data and conduct analyses to understand why these accessions are different.

Cluster analysis (CA)

Cluster analysis (CA) is a statistical technique used to group observations based on similarities within a dataset. Ward’s method begins by treating each observation as a separate cluster and aims to minimize the total variance within each cluster. When two clusters are merged, it selects merges that result in the least increase in total variance, often leading to more homogeneous groups. On the other hand, Euclidean distance measures the straight-line distance between two data points, calculated by taking the square root of the sum of the squares of the differences between their coordinates; this is used to assess the similarity or dissimilarity between points. A shorter Euclidean distance indicates that the points are more similar, while a longer distance suggests greater dissimilarity. When used together, Ward’s method and Euclidean distance provide an effective approach to understanding and grouping complex datasets; this combination is commonly preferred in data analysis and classification processes, as it enhances homogeneity within clusters and highlights similarities between observations46. The dendrogram created using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance is presented in Fig. 4. The dendrogram generated using Ward’s method and Euclidean distance provides a clear visualization of the relationships among the accessions. The initial division into two primary groups, A and B, shows distinct morphological or genetic characteristics that differentiate these sets. The subsequent subdivision into smaller subgroups (A1, A2, B1, and B2) indicates a more refined categorization, highlighting the presence of further variability within each main group. Notably, the differing numbers of accessions in each subgroup (18 in A1, 29 in A2, 19 in B1, and 34 in B2) imply varying degrees of similarity among the accessions. This structured classification can be instrumental in understanding the genetic diversity within the studied population, allowing researchers to identify specific traits and relationships that may be relevant for future breeding programs or ecological studies. Overall, this dendrogram serves as a valuable tool for interpreting complex data and guiding further investigation into the characteristics of these accessions.

ISSR analysis

ISSR analysis is a molecular biology technique used to study DNA polymorphism. ISSR analysis amplifies specific regions of the DNA using specific primers, allowing for the identification of genetic differences between individuals or species. It is commonly used in examining the genetic structures of plant and animal species, assessing diversity, and species identification. Due to its low cost and rapid nature, ISSR analysis is frequently preferred in genetic research. Additionally, this technique provides valuable information in areas such as genetic mapping and population genetics47.

In this study, 10 different ISSR primers were used to determine the genetic diversity of persimmon (D. kaki) accessions (Table 5). The total number of bands varied between 8 [(GA)8C] and 23 [(AG)8YT], resulting in a total of 139 countable bands from these primers. It was determined that 128 of these 139 countable bands were polymorphic. The number of polymorphic bands ranged from 6 [(GA)8C] to 23 [(AG)8YT]. The average band length varied between 100 and 2000. The total number of bands per primer was 13.9, and the number of polymorphic bands was 12.8. The polymorphism rate was determined to be an average of 91.44%. A study conducted in China using 11 ISSR primers reported a total band number of 135, a polymorphic band number of 135, and a polymorphism rate of 100%. The average number of bands and polymorphic bands per primer was found to be 12.2715. A similar study conducted in Russia reported that five out of 10 ISSR primers demonstrated clear polymorphisms and reproducible results, while the other ISSR primers showed low amplification quality and were excluded from the analysis. Consequently, a total of 72 bands were identified using the five effective ISSR primers, resulting in a 94.44% polymorphism rate for D. kaki and a 33.33% polymorphism rate for D. lotus. The number of bands in five ISSR primers was detected to vary between 8 and 175.

In the study, the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) was used to create a dendrogram to assess the molecular diversity of persimmon (D. kaki) accessions (Fig. 5). The similarity index among 100 persimmon accessions ranged from 0.41 to 0.96. In the dendrogram, the accessions were divided into two main groups, which were subsequently further split into two subgroups each. The A1 subgroup contained 10 accessions, the A2 subgroup had 52 accessions, the B1 subgroup included 16 accessions, and the B2 subgroup comprised 22 accessions. In this study, the accessions of the same species exhibited both genetic similarity and notable differences. This phenomenon can be attributed to natural gene exchange resulting from cross-pollination in the wild, as well as the ISSR marker systems, which target random regions within the genome48. Yuan et al.15 determined the similarity index to be between 0.32 and 0.99 using ISSR markers in persimmon accessions. Our similarity index finding aligns with the value ranges identified by the researchers.

High heterozygosity increases the likelihood of individuals exhibiting resistance to environmental stress factors (such as drought, pests, diseases, and extreme temperature fluctuations) by providing a broader genetic pool. This genetic diversity allows populations to adapt more quickly to changing environmental conditions, which is a critical factor for long-term survival and productivity.

Additionally, high variability in traits such as fruit size, color, and disease resistance is beneficial for the overall stability of the population. This diversity provides breeders with genetic material that can be used to develop improved cultivars with desired characteristics, such as higher yield, better fruit quality, or greater resistance to biotic and abiotic stress.

Genetically diverse populations also tend to have a higher level of ecological interaction, contributing to the improvement of ecosystem services such as pollination, soil fertility, and pest control. Furthermore, the maintenance of diversity helps reduce risks such as genetic bottlenecks or inbreeding depression by increasing the likelihood that some individuals will thrive under various ecological conditions.

High heterozygosity and genetic variability provide significant advantages not only for the survival and adaptation of fruit species to environmental changes but also for breeding programs aimed at enhancing fruit productivity and sustainability.

Overall, our findings comprehensively highlight the genetic diversity present within the studied persimmon accessions, which has significant practical applications in breeding programs, market potential, and ecological strategies. This diversity has been observed to directly impact the species’ adaptability, resistance to environmental stresses, and productivity. Specifically, this genetic variability offers a crucial resource for achieving agricultural goals such as improving fruit quality and increasing yield, thus enabling the development of more resilient and high-yielding cultivars. Additionally, a better understanding of the phenotypic variations shaped by environmental factors could guide the cultivation of cultivars that are better adapted to local climate and soil conditions.

The impact of observed genetic diversity on market potential could enable a more targeted selection of preferred fruit traits in commercial agriculture. Genetic diversity not only facilitates the development of higher-yielding and more resilient cultivars but also enables the introduction of new cultivars with commercially desirable fruit quality to the market. Furthermore, in terms of environmental sustainability, the role of this diversity in ecological strategies is significant; naturally occurring accessions provide valuable genetic resources for sustainable agricultural practices, contributing to the stabilization of agricultural ecosystems.

Consistent patterns observed across different studies reinforce the accuracy and reliability of our findings, showing that these genetic variations are of great importance not only for future breeding efforts but also for long-term economic and ecological strategies. For instance, the genetic diversity shown to provide resilience against varying environmental conditions could aid in the development of cultivars capable of withstanding global challenges such as climate change. Therefore, the findings of our study play an important guiding role in both commercial agriculture and sustainable agricultural strategies.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the genetic diversity among persimmon (D. kaki) accessions using morphological, pomological, and ISSR markers. The findings reveal significant genetic variations between accessions, offering a rich germplasm that can be utilized for both breeding and conservation efforts. The identification of promising genotypes, including ‘P78’, ‘P7’, ‘P48’, ‘P29’, ‘P44’, ‘P25’, ‘P5’, ‘P98’, ‘P80’, ‘P50’, ‘P37’, ‘P77’, ‘P57’, ‘P56’, ‘P41’, ‘P73’, ‘P39’, ‘P65’, ‘P72’, and ‘P61’, provides a strong foundation for improving the quality and adaptability of local persimmon accessions in future research and breeding programs. These genotypes are particularly valuable for enhancing fruit quality, disease resistance, and environmental adaptation.

This research fills an important gap in persimmon research in Türkiye, as previous studies have generally focused on limited morphological traits or regional varieties. By integrating ISSR markers with morphological and pomological evaluations, this study presents a more holistic view of the genetic diversity within persimmon populations across the country.

The results suggest several key directions for future research. Investigating the ecological adaptations of persimmon genotypes, particularly focusing on drought resistance, cold tolerance, and other climate-related traits, will be crucial for improving the resilience of persimmon varieties. Moreover, expanding the use of genetic markers such as SSR and SNP could provide deeper insights into the genetic basis of traits like fruit size, ripening time, and resistance to diseases and pests. Additionally, the promising genotypes identified in this study should be used in hybridization programs to improve yield, disease resistance, and fruit quality.

The data generated in this study is highly valuable for developing conservation strategies and establishing genetic banks for persimmon. The identification of broad genetic diversity underscores the importance of preserving local genotypes for future use. ISSR markers are effective tools for monitoring genetic diversity and can be applied in genetic banks to ensure the preservation of valuable genetic material. Moreover, the presence of outlier accessions, which exhibit significant deviations from the majority, suggests that these genotypes may harbor unique traits that could be beneficial under specific agricultural or environmental conditions. These outlier genotypes should be prioritized for conservation, as they may provide valuable genetic material for future breeding efforts and ecological adaptation strategies.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the complexity of genetic relationships among persimmon accessions and the significance of conserving this diversity for sustainable agricultural practices. The insights gained from this research will contribute to the development of effective management strategies to ensure the long-term sustainability of persimmon cultivation in Türkiye and support its conservation as a valuable crop for future generations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yesiloglu, T., Cimen, B., Incesu, M. & Yilmaz, B. Genetic diversity and breeding of Persimmon. Breeding and health benefits of fruit and nut crops. IntechOpen 21–46. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.74977 (2018).

Ray, P. K. Breeding Tropical and Subtropical Fruits (Springer, 2002).

Tuzcu, Ö. et al. Growing and status of subtropical and tropical fruit species in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 2nd FAO—MESFIN Meeting. 7–8 (1994).

Yıldız, M., Bayazit, S., Cebesoy, S. & Aras, S. Molecular diversity in persimmon (Diospyros kaki L.) cultivars growing around Hatay province in Turkey. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 6 (20), 2393–2399. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB2007.000-2375 (2007).

Samarina, L. S. et al. Genetic diversity in Diospyros germplasm in the western caucasus based on SSR and ISSR polymorphism. Biology 10 (4), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10040341 (2021).

Martins, S. et al. Western European wild and landraces hazelnuts evaluated by SSR markers. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 33, 1712–1720. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-015-0867-9 (2015).

Yildirim, N., Ercişli, S., Ağar, G., Orhan, E. & Hizarci, Y. Genetic variation among date plum (Diospyros lotus) genotypes in Turkey. Genet. Mol. Res. 9 (2), 981–986 (2010).

Mansoory, A., Khademi, O., Naji, A. M., Rohollahi, I. & Sepahvand, E. Evaluation of genetic diversity in three diospyros species, collected from different regions in Iran, using ISSR and SCoT molecular markers. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 22 (1), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538362.2022.2034563 (2022).

Badenes, M. et al. Genetic diversity of introduced and local Spanish persimmon cultivars revealed by RAPD markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 50, 579–585. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024474719036 (2003).

Yonemori, K. et al. Relationship of European persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) Cultivars to Asian cultivars, characterized using AFLPs. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 55, 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-007-9216-7 (2008).

Guo, D. L. & Luo, Z. R. Genetic relationships of some PCNA persimmons (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) From China and Japan revealed by SRAP analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 53, 1597–1603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-005-8717-5 (2006).

Guan, C. et al. Genetic diversity, germplasm identification and population structure of Diospyros kaki Thunb. From different geographic regions in China using SSR markers. Sci. Hort. 251, 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.02.062 (2019).

Zeljković, K. M., Bosančić, B., Đurić, G., Flachowsky, H. & Garkava-Gustavsson, L. Genetic diversity of pear germplasm in Bosnia and Herzegovina, as revealed by SSR markers. Zemdirbyste-Agriculture 108 (1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.13080/z-a.2021.108.010 (2021).

Liang, Y. et al. Genetic diversity among germplasms of Diospyros kaki based on SSR markers. Sci. Hort. 186, 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2015.02.015 (2015).

Yuan, L., Zhang, Q., Guo, D. & Luo, Z. Genetic differences among ‘Luotian-tianshi’ (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) genotypes native to China revealed by ISSR and IRAP markers. Sci. Hort. 137, 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2012.01.027 (2012).

Deng, L. et al. Investigation and analysis of genetic diversity of Diospyros germplasms using SCoT molecular markers in Guangxi. PLoS One. 10 (8), e0136510. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136510 (2015).

Zhou, L. et al. Evaluation of the genetic diversity of mango (Mangifera indica L.) seedling germplasm resources and their potential parents with start codon targeted (SCoT) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 67, 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-019-00865-8 (2020).

Mohammadzedeh, M., Fattah, R., Zamani, Z. & Khadivi-Khub, A. Genetic identity and relationships of hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) landraces as revealed by morphological characteristics and molecular markers. Sci. Hort. 167, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2013.12.025 (2014).

Ferreira, J. J., Garcia, C., Tous, J. & Rovira, M. Structure and genetic diversity of local hazelnut collected in Asturias (Northern Spain) revealed by ISSR markers. VII Int. Congress Hazelnut. 845, 163–168. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2009.845.20 (2009).

Reddy, M. P., Sarla, N. & Siddiq, E. A. Inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism and its application in plant breeding. Euphytica 128, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020691618797 (2002).

González, A., Wong, A., Delgado-Salinas, A., Papa, R. & Gepts, P. Assessment of inter simple sequence repeat markers to differentiate sympatric wild and domesticated populations of common bean. Crop Sci. 45 (2), 606–615. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2005.0606 (2005).

Grygorieva, O. et al. Morphological characteristics and determination of volatile organic compounds of Diospyros virginiana L. genotypes fruits. Slovak J. Food Sci./Potravinarstvo 11(1), 612–622 (2017).

Khademi, O., Erfani-Moghadam, J. & Rasouli, M. Variation of some Diospyros genotypes in Iran based on pomological characteristics. J. Hortic. Postharvest Res. 5 (4), 323–336 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of genetic diversity in persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) germplasms based on large-scale morphological traits and SSR markers. Sci. Hort. 313, 111866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2023.111866 (2023).

Martínez-Calvo, J., Naval, M., Zuriaga, E., Llácer, G. & Badenes, M. L. Morphological characterization of the IVIA persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) germplasm collection by multivariate analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 60, 233–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-012-9828-4 (2013).

Yilmaz, B., Genç, A., Çimen, B., İncesu, M. & Yeşiloğlu, T. Characterization of morphological traits of local and globalpersimmon varieties and genotypes collected from Turkey. Turk. J. Agric. For.. 41 (2), 93–102. https://doi.org/10.3906/tar-1611-27 (2017).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12, 39–40 (1990).

Uzun, A., Gulsen, O., Kafa, G. & Seday, U. Field performance and molecular diversification of lemon selections. Sci. Hort. 120 (4), 473–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2008.12.003 (2009).

JMP ®. https://www.jmp.com/en_us/home.html. Accessed 14 Oct 2024.

OriginLab ®. https://www.originlab.com/. Accessed 14 Oct 2024.

Hammer, Ø., Harper, D. A. T. & Ryan, P. D. Past: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 4 (1), 9 (2001).

Rohlf, F. J. NTSYS-pc: Numerical Taxonomy and Multivariate Analysis System, Version 2.1 (Exeter Publishing, 2000).

Sneath, P. H. A. & Sokal, R. R. Numerical Taxonomy (Freeman, 1973).

Yildiz, E. et al. Assessing the genetic diversity in hawthorn (Crataegus spp.) genotypes using morphological, phytochemical and molecular markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 70 (1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-022-01414-6 (2023).

Khadivi, A., Mirheidari, F., Moradi, Y. & Paryan, S. Phenotypic and fruit characterizations of Prunus divaricata Ledeb. Germplasm from the north of Iran. Sci. Hort. 261, 109033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109033 (2020).

Gundogdu, M. et al. Organic acids, sugars, vitamin C content and some pomological characteristics of eleven hawthorn species (Crataegus spp.) from Turkey. Biol. Res. 47, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/0717-6287-47-21 (2014).

Einollahi, F. & Khadivi, A. Morphological and pomological assessments of seedling-originated walnut (Juglans regia L.) trees to select the promising late-leafing genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 24 (1), 253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04941-9 (2024).

Prasad, K., Jacob, S. & Siddiqui, M. W. Fruit maturity, harvesting, and quality standards. In Preharvest modulation of postharvest fruit and vegetable quality. Acad. Press. 41–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809807-3.00002-0 (2018).

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S. & Ullman, J. B. Using Multivariate Statistics. Vol. 6. 497–516. (Pearson, 2013).

Stockemer, D., Stockemer, G. & Glaeser, J. Quantitative Methods for the Social Sciences. Vol. 50. 185. (Springer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99118-4

Khadivi, A., Mirheidari, F. & Moradi, Y. Morphological variation of persian oak (Quercus brantii Lindl.) In Kohgiluyeh-Va-Boyerahmad Province, Iran. Trees. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-024-02528-3 (2024).

Khadivi, A., Mirheidari, F., Saeidifar, A. & Moradi, Y. Morphological characterizations of Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 71(5), 1837–1853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-023-01740-3 (2024b).

Khaleghi, A. & Khadivi, A. Morphological characterizations of wild nitre-bush (Nitraria schoberi L.) specimens. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 71 (1), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-023-01635-3 (2024).

Jolliffe, I. T. Principal Component Analysis for Special Types of Data. 338–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-22440-8_13. (Springer, 2002).

Kramer, M. A. Nonlinear principal component analysis using autoassociative neural networks. AIChE J. 37 (2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690370209 (1991).

Everitt, B. S., Landau, S., Leese, M. & Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis. 5th edn (Wiley, 2011).

Zietkiewicz, E., Rafalski, A. & Labuda, D. Genome fingerprinting by simple sequence repeat (SSR)-anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification. Genomics 20 (2), 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1006/geno.1994.1151 (1994).

Yorgancılar, M., Yakışır, E. & Tanur Erkoyuncu, M. The usage of molecular markers in plant breeding. J. Bahri Dagdas Crop Res. 4 (2), 1–12 (2015).

Acknowledgements

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. YT and CA Investigation, project administration, resources, software. YT and KUY Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, validation. YT and AK Supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. YT, EHS, DSM, and TV Conceptualization, and validation, visualization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement specifying permissions

For this study, we acquired permission to study persimmon (D. kaki) issued by the Agricultural and Forestry Ministry of the Republic of Türkiye.

Statement on experimental research and field studies on plants

The either cultivated or wild-growing plants sampled comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and domestic legislation of Türkiye.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tunç, Y., Aydınlıoğlu, C., Yılmaz, K.U. et al. Determination of genetic diversity in persimmon accessions using morphological and inter simple sequence repeat markers. Sci Rep 15, 2297 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86101-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86101-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Taxonomic significance of morphological and molecular variation in Egyptian Malvaceae species

BMC Plant Biology (2025)

-

Study on the characteristics of genetic diversity and population structure of a rare and endangered species of Rhododendron nymphaeoides (Ericaceae) based on microsatellite markers

BMC Plant Biology (2025)

-

Biochemical, nutritional, and nutraceutical properties of cactus pear accessions

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Comparative evaluation of red and white aril genotypes of Manila tamarind for fruit physicochemical and bioactive attributes

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Determination of gene association analysis of some leaf traits in mulberries using simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers

Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (2025)