Abstract

Currently, bioabsorbable polymer stents are utilized to mitigate the risk of late stent restenosis in cardiovascular applications. In this context, we propose a novel assembly that integrates polycaprolactone (PCL) nano-fibers and oxidized starch (OS) with iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) to create a rigid-swelling scaffold for cardiovascular stents. This study fabricates the nanocomposite (NC) using a combination of electrospinning and electrospray techniques. The stent body is formed by leveraging the self-adhesive (SA) properties of multiple NC sheets, resulting in a multilayer (ML) structure. To achieve the desired stent shape, we employed the CO2 laser cutting method on a specific pattern after rolling the prepared sheets in two steps: OS hydration followed by melting the polymer between layers during the cutting process. Our results show that the multilayer structure of the cardiovascular stent body demonstrates favorable in vitro mechanical properties and biocompatibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is currently the leading cause of death in the world1 and is expected to continue to be the most common reason for death in the future. The disease is associated with the accumulation of oxidized lipoproteins in the extracellular matrix of intimate vascular tissue, leading to plaque formation. These processes damage the blood vessels at the plaque site, increasing the risk of vessel rupture or blood clots in that area. There are several treatments for this disease, including medication, balloon angioplasty, stent angioplasty, and surgical treatment. In recent years, the use of cardiovascular stents has become a preferred method due to the many advantages of this method over other therapies. Stent angioplasty is a preferred model in the treatment of atherosclerosis, performed to reduce blockage and restore blood by placing a vascular stent on the artery, dilating it at this point. Today, the use of cardiac stents has increased significantly due to their ease and effectiveness of artery occlusion treatment. Therefore, stent design, stent evaluation, and mechanical analysis of the most suitable different behaviors are important2,3. A stent is a tubular mesh-like object, and the size of the stent is relatively small. The stent provides a barrier that reduces the risk of the artery narrowing again and also supports the artery wall4. Restenosis occurs in more than 30% of patients after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty without stenting and in 20 to 30% of patients with stenting5. Complete destruction of a bioabsorbable stent liberates the vessel from its cage and potentially restores vascular anatomy as well as vasomotor responses, plasticity, physiological shear stress, and mechanotransduction6. Bioabsorbable polymers have been applied using a combination of synthetic polymers with the polymer polycaprolactone (PCL)7,8,9. PCL is a hydrophobic, biocompatible, semi-crystalline polymer that blends easily with a variety of synthetic and natural polymers10. After balloon deflation, immediate and acute stent recoil was observed in normal and diseased coronary arteries, the magnitude of which varied depending on the stent design. Low stent recoil during clinical examination is desirable to reduce the risk of subsequent restenosis11. A practical vascular stent should be non-toxic with self-expanding properties, fast expansion speed, and adequate mechanical support properties. However, there are no existing vascular stents that are all-inclusive12.

This study investigates a hybrid of OS based Fe3O4 nanocatalyst in thermoplastic (TPN) format and the polymer PCL for use in cardiovascular stents. However, low mechanical strength, inadequate cellular recognition sites, low bioactivity and hydrophobicity are the main disadvantages of PCL that limit its widespread use in biomedical applications. Blending with natural polymers are being investigated to maintain and benefit from the high potential of PCL while addressing the physicochemical and biological challenges10,13. The properties of PCL compounds with a slow decomposition rate and starch with a fast decomposition rate are quite different. In fact, when starch is added to PCL, the water absorption from PCL accelerates the decomposition rate14. Starch is a natural polymer composed mainly of two types of glucose polymers, amylose and amylopectin. The advantages of starch bioplastics are abundance, low cost, and biodegradability. However, most starch-based composites have low tensile strength and modulus15. One of the processes for producing improved bioplastics from starch is the thermoplastic (TP) process. The starch is mixed with a limited amount of water, heated and sheared to destroy its structure by the applied conditions and a homogeneous melt is obtained as starch TP16. The oxidation process increases the stability and reduces the swelling rate of starch in TP form. Our previous work on constructing TP from oxidized starch catalyzed by iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) demonstrated that the mechanical properties, swelling ratio, and stability of TP using IONPs were improved17. Some of the combination techniques include the use of TP melt blending of starch and PCL18, melt mixing and extrusion19, single nozzle electrospinning technology20, and coaxial electrospinning technology21. One of the advantages of using electrospinning technology over melt blending is that the nanofiber diameter size and the increased surface area of the polymer increase the rate of structural degradation of the nanofibers.

The present study used a two-nozzle electrospinning technique to form the TP composition of starch and PCL. The tube shapes created by the SA property of electrospun composite sheets can be cut using CO2 laser technique to achieve any desired pattern. The main novelty of this study is the use of two natural (oxidized starch@Fe3O4 NPs, TPN) and synthetic (PCL) agents in the form of nanocomposites for the vascular stent fabrication. Due to the time-consuming process of electrospinning-electrospraying, hybridization of several layers of nanocomposite sheets was used. By placing the created multi-layer nanocomposite in distilled water, the TPN in the structure swells by absorbing water, and as a result, after placing the sheets on top of each other, they stick together and hybridize with the adhesion created by the oxidized starch. In the 3D constructing of the stent, we used from 2D laser machining method as a novel and simple technique for fabricating of the stent (Fig. 1). The purpose of using oxidized starch as a green material in composite is to improve the mechanical properties of the PCL polymer and assist to building of multilayer stent. The in vitro stability of multi-layered scaffold was obtained by analyzing tensile and radial compressive strengths with appropriate results. Survival of HUVEC and L929 cells was assessed by both direct and indirect methods, and adhesion of HUVEC cells to the nanocomposite surface was successfully performed. Blood compatibility of samples was also assessed by PT, APTT, hemolysis analysis, and platelet adhesion tests. It can be said that it has a gradual degradation rate while maintaining its structural integrity. Therefore, this novel structure can be used as a vascular stent. Novelties of this work:

-

Hybrid nanocomposite approach: the study introduces a novel combination of natural (oxidized starch@Fe3O4 nanoparticles) and synthetic (PCL) materials in the fabrication of vascular stents. This hybrid approach aims to enhance the mechanical properties and biocompatibility of the stents compared to PCL as a conventional material.

-

Electrospinning and layering technique: the use of a two-nozzle electrospinning technique to create nano compositions formed from starch and PCL is an innovative method for stent fabrication. This method allows for the development of multi-layered structures that can be customized in terms of size and shape using CO2 laser machining.

-

Focus on biodegradability and mechanical enhancement: the incorporation of environmentally friendly oxidized starch aims to improve the mechanical properties of PCL while being biodegradable, addressing both mechanical and ecological concerns in stent design.

Materials and methods

Oxidation of starch

Iron oxide nanoparticles were synthesized by co-precipitation reaction with a combination of FeCl3.6 H2O and FeCl2.4 H2O (Merck, ≥ 99%) in molar ratio (2: 1) and NH4OH (Merck, 25%) in an aqueous medium with argon flow injection22. A certain amount of corn starch (1 g) dispersed in 100 ml of deionized water, then placed in a reactor at 80 °C until a gelled starch obtained with a pH adjusted to 5 with NaOH (Merck, 99%) and HCL (Merck, 37%)23. Finally, 2.5 mg of IONP as catalyst and 200 µL of H2O2 (Merck, 30%) were carefully added into the reactor. At this stage, the reaction temperature was 50 °C for 1 h, thus reaching the highest degree of oxidation17.

Fabrication of TPs

The TP synthesis procedure was fully described in our previous work17. The TP process was used for plasticization of OS by hydrophobic and hydrophilic plasticizers. Oxidized starch (1 g), 50 µL of sesame oil (prepared from herbal medicine store, Iran), 20 µL citric acid (Merck, 99%) at 0.1 g/mL and glycerol (200–250 µL, Merck, ≥ 99.5%) have been used in the formation of TP products. The process was thoroughly and uniformly stirred in a glass reactor (total volume of 40 mL) at a temperature of 80–90 °C to produce a viscous solution. As the water evaporated, the amount of reaction solution decreased from 40 mL to about 10 mL.

Fabrication of NC from TP and polycaprolactone polymer

A two-nozzle electrospinning device (FNM Company, Iran) was used in this process. The TPN sample was completely immersed at 2.5% w/v (starch) in dimethyl sulfoxide solvent (DMSO, Merck 99%) and stirred for 24 h at 50 °C. The contents of the sample were placed into one of the syringe pumps. The injection rate was set at 1 ml/h. In another syringe pump, a 13.3% w/v polycaprolactone polymer solution (Mw = 80000, Sigma Aldrich) combined chloroform/methanol (1/2) (99% Merck Millipore) and beeswax (0.44% w/v) was considered. The PCL injection rate with beeswax (PBW) solution was set at 0.3 mL/h and the voltage of the electrospray device was at 13 kV on both nozzles. A thin film was formed by spraying the sample onto an aluminum foil-covered collector and the drum speed was taken as 1000 rpm. About 30 to 40% of this composite is related to TPN. In this process, a polymer sheet was prepared from 3 batches of PBW solution (2.25 ml of solvents, 0.3 g PCL and 0.01 g BW) and 3 batches of TPN solution (6.75 ml of 2.5% w/v in DMSO solvent). To obtain nanofibers with smaller diameters and according to nanofiber formation tests and experiments, the PBW solution should be at 13.3% (W/V). The highest TPN concentration in DMSO to obtain a transparent and homogeneous solution was achieved at 2.5%. Furthermore, the final combination after evaluation in ML sheet forming and laser cutting step (no melting or burning phenomenon), we consider 30–40% TPN in NC. Therefore, the injection rate of PBW and TP solutions will be different.

Characterization of OS and TP

In this section, OS samples were used in layer form according to the casting method and had a thickness of about 100–200 μm. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was used to investigate the formation of CO and COOH functional groups in OS. This analysis was done by Bes TeK device (EA 10) on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha spectrometer using an Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) operating at 12 kV. The binding energy was calibrated based on the C 1s peak at 285 eV. The TGA/dTG gravimetric analysis was performed by Mettler Toledo (TGA-DSC 1) between 40 and 700 °C for 80 mg of three samples of OS, TP and NC. The HRTEM image (HRTEM, FEI Tecnai G2 F20 SuperTwin TEM with accelerating voltage: 200 kV) was prepared by passing through the OS with NPs. The SEM-EDX images (Philips XL30, at 20 kv, F.E.I company) were taken from samples after sputtering.

Preparation of ML structure of NC film

Because the syringe injection speed in the electrospinning device is slow, it takes time to achieve the appropriate thickness. Additionally, a suitable compressive strength of about 20 kPa is required to achieve a cylindrical stent structure in the electrospun device. For this purpose, the ML structure was used to produce the desired body thickness (about 200–300 μm). In this technique, an electrospun sheet was placed on aluminum foil in distilled water for 1–2 h. Then, the NC layer could be easily separated from the aluminum sheet. After separating the composite from the sheet, several NC layers were placed on top of each other and bonded. This adhesive property is due to the presence of DI water and the interaction of functional groups in the sticky structure of OS. The ML structure was fabricated with sufficient compressive strength without the need for any new adhesive materials or solvents.

Three-dimensional stent fabrication

Electrospun sheets from simultaneous electrospinning of TP starch and PCL polymer were applied to aluminum foil. These leaves easily separate from the foil by absorbing water and sticking together. This creates a thicker 4-layer (FL) form used to make stents. In the next step, the FL film could be wrapped (two times) on a cylindrical mold in the undried state, then the cylinder was compacted on aluminum foil in a rectangular 2D state according to the laser cutting process. The rectangle was dried in room temperature cut into the desired pattern (strut thickness = 200–250 μm, strut width = 600–650 μm) using a CO2 laser cutting process. In this setup, a commercial CO2 laser (ROTEC Company, RT4040) was used with a maximum average output power of 10–11%, minimum power output of 5–6%, and speed of 10 mm/s. The design used for the stent was a specific origami pattern, made to a dimension (width = 2.7 mm and length = 16–17 mm). Then, the cylindrical mold was inserted into the fabricated tube (outer diameter = 1.9–2 mm) and placed in DI water for 0.5 h, finally, the cylindrical mesh sample was dried at room temperature after 24 h. Full integration of the 3D structure at the final stage involves merging the PBW at the laser-cut edge and filling the space between the layers with OS swelling.

Investigation of mechanical stability of NC

The mechanical properties of the NC samples were tested with dimensions of 1 × 2 cm (tensile dimension equal to 1 cm). The tensile strength of the samples was tested using a mechanical tensile analyzer (ZwickRoell Tensile Tester) on single-layer samples (thickness 30–40 μm) and ML samples (thickness 100–200 μm for 4 layers). At moving speeds of 1 mm/min and 2 mm/min, respectively. The tensile strength of the samples was measured before and after incubation at pH = 7.4, 37 °C and shaking at 100 rpm for 20 weeks (for single layer) and 12 weeks (for ML).

To evaluate the mechanical stability of the cylindrical structure (diameter = 3.4 mm and length = 1 cm), a compressive strength (Radial compression) analysis was used to apply a radial force to the cylindrical structure. Mechanical tensile analysis (Zwick Roell tensile tester with flat plate radial compression technique) was performed at a moving speed of 1 mm/min24. The compressive strength of the sample was measured before and after incubation at pH = 7.4, 37 °C and under shaking at 100 rpm at intervals between 2, 4 and 12 weeks of incubation.

Evaluation of the swelling ratio

Samples were placed in quadruplicate in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) at approximately 37 °C and rpm = 100. After drying the surface with a lint-free cotton cloth, the samples were weighed (M2). At different times, the mass difference compared to the dry sample (M1) was determined and the swelling ratio was determined according to Eq. 1.

Hemocompatibility investigation

Hemolysis

Blood samples and transferred to PT tubes containing citrate buffer. First, blood was diluted 4/5 with PBS. Each 1 cm2 NC sample was incubated with 900 µL of PBS in triplicate for 1 h, and 100 µL of diluted blood sample was added to each sample and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a shaking incubator. The samples were then centrifuged at 37 °C and 3000 rpm for 5 min, and the UV absorbance (Ai) of hemoglobin in the supernatant solution (i) of each sample was measured at 545 nm using a Cytation apparatus. Hemolysis rate (HR) was calculated using Eq. 2 calculated. In this formula, distilled water was considered as a positive control and PBS was considered as a negative control. all experiments involving human subjects were conducted with appropriate institutional approval (IR.TUMs.VCR.REC.1398.184) and informed consent obtained from all subjects and legal guardians.

Measurement of the clotting time and platelet adhesion

To prepare platelet-rich plasma (PRP), Human blood samples were collected from volunteers into PT tubes containing citrate buffer. Plasma was obtained by centrifuging whole blood at 1000 rpm for 15 min at 37 °C. For this purpose, 1 cm2 of scaffold samples were examined, and 1 ml of PRP was added to each sample (n = 3) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Surface plasma was then removed from the samples and prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) were measured using an ACLELITE device. Composite samples (PCL, PBW, NC) were observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Philips XL30, 20 Kv) up to a size of 1 cm2. First, 0.5 mL of PRP was added to each sample and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h, after which the plasma was removed. Scaffolds were washed three times with PBS and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Merck, 25%) for 0.5 h. The surface of the sample was coated with gold and photographed using a scanning electron microscope.

Cell viability investigation

In direct cell culture conditions

For the initial assessment of cytotoxicity, 3 cm2 samples were placed in approximately 500 µL of medium. Samples were incubated at 37 °C and sample extracts were prepared after incubation for 24, 48, and 72 h. For the growth of HUVEC endothelial cells and L929 fibroblasts (purchased from Pasture Institute, Iran), DMEM and DMEM F12 (Bio Idea company) containing 10% FBS serum (Biosera) were used at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Cells were cultured in four replicates at a cell density of 105 cells/ml in 96 cell culture plates. After 24 h, the initial medium was removed and 100 µL of extract sample was added to each well. After 24 h, the medium containing the extract was removed and cell growth and proliferation was measured at 570 and 630 nm in Alamar Blue solution (10%).

Direct cell culture conditions

To evaluate the cytotoxicity on the NC surface, direct cell seeding on the NC was used. DMEM F12 and DMEM with 10% FBS at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in humidified air were used to assess cell viability directly related to HUVEC endothelial cells and L929 fibroblasts (for 48 h). The 1 cm2 sample with a thickness of approximately 30–40 μm was sterilized with penicillin/streptomycin (1%), washed with PBS and medium, and then placed in a 48-well cell culture plate with the wells completely covered. Cells were cultured in triplicates at a cell density of 105 cells/ml, and the medium in the wells was changed daily. The OD absorbance of Alamar Blue (10%) was measured at 570 and 630 and cell viability was calculated.

Cell attachment test

Cell adhesion is mediated by HUVEC endothelial cells. NC samples were prepared, sterilized with penicillin/streptomycin (1%), and washed with PBS. Cells were cultured on the samples for 48 h at a cell density of 104 cells/ml, fixed with paraformaldehyde (4%), and treated with 100 µL DAPI solution (1 µg/ml) for fluorescence imaging. Fixed samples were coated with gold for SEM analysis.

Statistical analysis

In this study we used two-way and one-way ANOVA analysis and obtained the P-value (P) from Tukey’s multiple comparison method. ns (non-significant) represented P > 0.05 and *, **, ***, **** were used for P < 0.05, P < 0.01, P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001, respectively.

Results and discussions

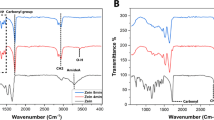

Investigation of oxidation reaction XPS analysis

The C 1s spectrum of OS with NPs (Fig. 2A) had three deconvoluted peaks corresponding to C–C and C–H bonds at 285.09 eV, C–O and C–O–C bonds at 286.21 eV, and C = O and O–C = O (for COOH) groups were assigned at 288.01 eV25,26. Figure 2B showed the O 1s XPS spectrum of OS-containing NPs. The O 1s-XPS spectrum was characterized by three peaks at 531.31 eV assigned to the C = O bond, with bond energies of 532.85 eV related to the C–O and C–OH bonds, and 534.76 eV based on the O–C = O bond27,28. Full spectrum of XPS analysis represented in Fig. 2C. The results confirmed the successful oxidation with the formation of C = O and COOH within the OS.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was used to investigate the formation of C = O and COO functional groups in OS, (A) the high-resolution and deconvoluted of XPS C1s spectra, (B) the high-resolution and deconvoluted of XPS O1s spectra, (C) general XPS spectra of OS, (D) transmission electron microscope (TEM) image after starch oxidation, (E) the contact angle of samples, (F) HRTEM of the IONPs in OSNP, significancy for (E) was evaluated by one-way ANOVA test and obtained the P-value (P) from Tukey’s multiple comparison method, * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001.

Thermogravimetry analysis for OS, TP and NC

The TGA thermograms of OS with NP (OSNP), TPN, and NC, as well as the first derivative curves in the dTG analysis, are presented in Figure S1A and B. Due to the presence of plasticizers in TP, the behavior of the mass loss curve is not the same in OSNP and TPN. The first mass loss was probably due to dehydration of the samples, from 130ºC to the beginning of OSNP decomposition. In the TPN curve, the second mass loss can be attributed to the volatilization of glycerol29 and citric acid. Mass loss occurs at temperatures from 226 °C to 350 °C with a peak at 310 °C for OS, from 230 °C to 355 °C with a peak at 312 °C for TPN, and from 310 °C to 700 °C with a peak at 395 °C for the corresponding NC. In the NC curve, the presence of PBW in the composite increased the peak position and increased the depolymerization temperature. The PCL polymer in PBW has a depolymerization temperature (DT) of approximately 415 °C30, while TPN, another component of the composite, has a DT of around 312 °C. When these two materials are combined, the resulting composite exhibits a DT of 395 °C. This temperature is higher than that of TPN alone but lower than that of PCL alone, indicating that the presence of PCL in the composite enhances overall thermal stability and influences the degradation behavior.

Surface wettability investigation

To evaluate the wettability of starch surfaces, contact angle analysis was used where distilled water was the desired liquid. The contact angle size (at 5 s) after placing water drops on the starch film surface was studied using a device (WCA, made in Iran). Figure 2E shows the contact angle was measured for normal starch without oxidation (NS) and for normal starch with added IONPs (NSNP) without any chemical reaction. The presence of IONPs in the starch resulted in a decrease in the contact angle. In contact angle relative to the OSNP, a strong increase in the contact angle was observed (compared to OS), which may be due to the presence of a larger number of C = O groups and increased hydrophobicity of the surface. Furthermore, in hydrophilic solid surfaces (contact angle < 90°), the apparent contact angle decreases as the roughness of the solid surface increases31. Therefore, we can conclude that the surface roughness of OSNPs decreased and the contact angle increased. However, incorporating the OSNP in NC significantly decreased the contact angle of the surface (compared to PBW).

Evaluating the nanostructures by HRTEM and SEM images

After the oxidation reaction, the interaction of Fe3O4 NPs with starch was shown using TEM in Fig. 2D. Before the oxidation process, the IONPs could be easily separated from the starch solution; however, after oxidation, the IONPs became completely associated with the OS. The oxidized sample was separated by the magnet 3–4 times and finally, a fraction of NC completely related to NPs and OS were detected by TEM imaging where the average particle size was about 7.3 ± 1.2 nm. HRTEM images passing through the NPs were shown in Fig. 2F. The synthesized IONPs had a fractal lattice polycrystalline structure and the distance between the two crystal layers was measured to be about 0.20 ± 0.02 nm. This description indicates that the nanoparticles are composed of multiple small crystallites, each having a unique orientation, which together form a complex three-dimensional structure resembling a fractal pattern. Fractal structures are characterized by self-similarity and intricate patterns that repeat at different scales. This feature can contribute to unique physical and chemical properties, making the IONPs particularly interesting for various applications in fields like biomedicine, catalysis, and magnetic materials. Moreover, the spacing between the two crystal layers measurement, known as the interplanar distance, refers to the distance between adjacent planes of atoms in the crystal lattice of Fe3O417.

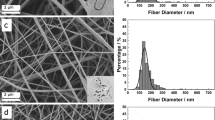

The Fig. 3A and B represented the schematic of using the two-electrospinning technique for TPN and PWB blending. After electrospinning to obtain PCL polymer fibers (112.9 ± 67.3 nm) (Fig. 3C) and PBW fiber with BW addition to PCL (Fig. 3D), the solution of PCL polymer was used at a concentration of 13.3% w/v in the solvent methanol and chloroform in a ratio of 1/2 for PCL nanofiber and with BW added at a concentration of 0.44% w/v for PBW nanofiber fabrication. The reduction in fiber diameter and suppression of bead formation was due to the addition of BW to the PCL solution. The diameter of PBW nanofibers was expected to be about 54.4 ± 15.9 nm. For NC composed from PBW and TP, a two-nozzle electrospinning device was used (according to the Fig. 3B, TPN was sprayed on one side, while PBW nanofibers were spun onto the collector on the other side). SEM images and size distributions of the NC fibers (60.34 ± 16.2 nm) were shown in Fig. 3E. There were protrusions on the lateral surface of the fibers associated with TP starch. These extensions were made in a circular shape and very fine fibers were stretched between parallel PBW fibers. TP nanofibers precipitated randomly during the processing of PBW fibers, and PBW fibers played a supporting role for TPN nanofibers. The diameter of the TPN nanofibers became 15.0 ± 2.9 nm and the diameter of the round particles became about 100–220 nm. In addition, the distribution of carbon, iron, and oxygen elements was shown in Fig. 3F, G, and H. The composite detail measured with the aid of using EDAX proven in Fig. 3I, on this determine the ratio of C, Fe and O factors is provided in extra seen points. The distribution of elements was mainly based on the uniform distribution of iron with the shape of the internal nanofibers and then the elements carbon and oxygen. During the stability test (5 months), in each NC sample, a uniform structure was observed at each stage. In each of the mechanical and cellular tests using different parts of the composite sample, the results were nearly identical. This electrospray process appears to enhance the distribution of the materials, resulting in a more cohesive and visually consistent product.

The NC process fabrication, (A) preparation of TP and PBW solution, (B) the electrospinning device with two syringe pump to hybridize the TP and PBW components in the NC, Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images, (C) PCL nanofibers, (D) PBW nanofibers, (E) NC nanofibers, (F) carbon element distribution pattern (blue dots), (G) Iron element distribution pattern (yellow dot) (H) distribution of oxygen element (violet dot), (I) Focused composite of the EDAX elements (C (blue dot), Fe (yellow dot) and O (violet dot)) on the surface of NC, (J) swelling ratio of the TP, TPN, PBW and NC, (K) the tensile stress analysis of the TP, TPN, PBW and NC.

The swelling ratio investigation

TP samples including TP and TP of OSNP (TPN) were placed at approximately 37 °C in phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4). As shown in the Fig. 3J, the water absorption rate of TP is higher than that of TPN and TP also begins to degrade after 90 min. This indicates that the structure of TPN due to the surface reaction of NP and functional groups such as carbonyl and carboxyl leads to higher stability and lower water absorption rate in aqueous media and under biological conditions. This Figure showed that the water absorption rate of PBW was higher than that of NC. After 10 h, it was evident that the water absorption content in NC (188 ± 15%) was higher than that in PBW (166 ± 30%). It can be concluded that the presence of TPN within the NC structure first decreased the rate of water absorption into the structure. In addition, TPN filled the empty space between fibers by swelling, and water absorption rate decreased as the porosity decreased. However, in PBW, the empty spaces between the nanofibers were filled with water, and more space was created by the nanofibers to absorb water32. After 10 h, it was obvious that the water uptake of NC was higher than the PBW. As a result, it can be said that the rate of water absorption in NC has decreased, but its capacity has increased. IONPs by catalytic effect for oxidation facilitate the oxidation of starch17, improving its structural integrity and degradation rate.

The mechanical analysis of the samples

To better evaluate the tensile strength of the TPs, NC, and PBW Fig. 3k was used. Wherein the tensile strength analysis for TP and TPN, TPN containing starch oxidized with NPs has a higher tensile strength due to the interplay of NPs to OS. We utilized IONPs to enhance the mechanical properties of oxidized starch (OS). The addition of IONPs increases the strength and stability of TPN (Fig. 3j and k). An increase in Young’s modulus and tensile strength was observed in NC compared to PBW, demonstrating mechanical improvement with the addition of TPN to PBW. However, the use of TPN in NC reduced elongation, which is a behavior commonly observed in filler-matrix composite structures. The decrease in elongation at break in filled polymer composites (NC) can be attributed to the fact that TPN, as a filler, typically exhibits much less deformation than the polymer matrix. Consequently, TPN causes the matrix to undergo greater deformation than the overall deformation of the composites33. In degradation state, the elongation increased beyond what was observed with PBW elongation; consequently, this reduction was offset during the degradation stage (2–12 weeks) and resulted in an overall improvement (Fig. 5A).

The process of (A) ML sheet fabrication, (B) Tube constructing and laser cutting, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images related to the composite in ML structure, (C) before, (D) after incubation for 30 min, (E) the edge melted in laser cutting, (F) the cross section of stent strut, (G) The diagram of BET nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm, (H) BJH pore-size distribution

The SEM morphology of the ML structure of NC

The ML structure was fabricated using water-swollen TPN, eliminating the need for additional adhesives or solvents. A custom mesh design for the stent body was created using CO2 laser cutting (Fig. 4A and B). These fabrication steps affected the ML structure, which was analyzed using SEM.

The mechanical stability of (A) single-layer membrane by tensile strength analysis after 20 weeks, (B) mechanical stability of ML membrane by tensile strength analysis after 12 weeks, (C) mechanical stability of coil-shaped structure by radial compressive strength analysis after 12 weeks, (D) weight reduction of composite sample after incubation in phosphate buffer for 20 weeks, incubation condition: at pH = 7.4, temperature = 37 ºC and rpm =100, (weight loss data points are presented as mean±SD for n=4)

The thickness of the ML samples after 30 min exposure to PBS and drying at room temperature was evaluated in the cross-sectional images of SEM analysis in Fig. 4C and D. The results showed that the layers were completely merged due to water absorption. Complete adhesion of the layers occurred through water absorption and activation of functional groups within the TP structure. The self-adhesive mechanism includes swelling of TPN between layers by water absorption and bonding of layers with TPN like gel forming according to SEM image (Fig. 4D). Delamination process was accrued in some samples with lower amount of TP (< 30%) therefore we used 30–40% of TP in NC. The morphology of the multilayer NC after laser cutting was analyzed by SEM (Fig. 4E and F). The shape of the laser cutting area after laser cutting was shown in Fig. 4E and the laser cutting edge with the width of the melting area was estimated to be about 140–150 μm. Furthermore, the surface morphology of NC was observed in the regions outside the melting zone, and the morphology of the NC surface produced porosity in these regions. A cross-sectional image inside the stent strut was shown in Fig. 4F and the layers were fully merged.

Investigation of Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis of NC structure

The specific surface area and pore size distribution of the prepared NC (density = 0.8 g/cm3) by nitrogen gas adsorption were analyzed (BET apparatus, TriStar II Plus 3.03, Micromeritics at T = 77 K). In addition, the physisorption analysis of nitrogen shows the adsorption-desorption isotherm (Fig. 4G) and the pore distribution diagram shows that mesoporous dimension34. The BET surface area was measured to be 212.35 m2/g. The NC samples showed a pore size distribution ranging from 1.6 to 45 nm and a total pore volume of 0.211 cm3/g (about 17% porosity) (Fig. 4H).

The stability of NC

To evaluate the mechanical stability of the single-layer film under incubation conditions (37 °C in PBS, rpm = 100), the tensile analysis was used in Fig. 5A. Furthermore, in Fig. 5B, the mechanical stability of the ML film was investigated by tensile analysis. The Young’s modulus and tensile strength of the single-layer membranes did not change after 2 weeks. However, Young’s modulus decreased rapidly within 4 weeks35 and the elongation at break (%) increased. But, over time, after 20 weeks, there was no visible change in Young’s modulus, but the variable elongation (%) decreased. This indicates that during this period the sample deteriorated and gradually lost its structural consistency. In Fig. 5B, the empty space between the layers reduced the ultimate tensile strength in the ML mode compared to the single layer. After exposing the ML samples to incubation conditions (37 °C in PBS, RPM = 100) after 2 weeks, Young’s modulus decreased and the elongation (%) increased.

The compressive strength at 70% of radial compression was about 25.4 ± 0.5 kPa, which was higher than that of the PCL sample (about 21.3 kPa)24. After incubating the samples in PBS, a decrease in compressive strength of up to 15–18 kPa was observed. This can be attributed to the decrease in thickness with water absorption (Fig. 4C and D). The decrease in compressive strength after 4 and 12 weeks was not noticeable from that after 2 weeks (Fig. 5C). Even after 12 weeks of incubation, the appearance of the ML tubes remained intact, with no signs of unfolding or collapse.

The mass loss (Fig. 5D) was due to the release of the polar parts of the NC in the polar environment generated by the potassium salt solution in PBS, indicating some degree of degradability of the composite. These polar moieties belong to the carboxyl, carbonyl, and hydroxyl groups of the TP structure. Although PCL polymer is one of the biodegradable materials, its degradation rate is very slow36 and it is much more stable than OS in an aqueous environment. However, its nanofiber structure increases the surface area to volume ratio. In general, it can be said that two factors increase the degradation rate of NC structures: TP and their nanostructures37. The mass loss of PBW was also evaluated and a small change (about 1–2%) in weight was obtained, indicating that PBW, due to its hydrophobic structure compared to NC, has a more stable structure. Therefore, the use of TPN in NC has the potential to increase the NC decomposition rate to an appropriate level.

This study showed that the monolayer membranes exhibited stable Young’s modulus for the first two weeks after implantation, followed by a significant decrease over the next four weeks. This initial stability is important for mechanical support in tissue engineering, but the subsequent decrease indicates a loss of structural consistency that may contribute to tissue integrity due to controlled degradation. After 20 weeks, the Young’s modulus stabilized, but the elongation at break decreased, indicating a continued deterioration of the material for tissue regeneration. The initial compressive strength of the NC tube slightly decreased in strength, maintained integrity over 12 weeks, indicating their suitability for load-bearing applications. The material exhibits some biodegradability from the release of polar components, while minimal mass loss in PBW indicates stability in environments exposed to moisture, making it suitable for long-term use.

Examination of the hemocompatibility of the NC

The two parameters PT and APTT shown in Figure S2A and B were used to investigate the clotting time of different combination groups (Control: PRP without any agent, TPN, PCL, PBW and NC). Their value was not significantly different from that of the control group. As a result, these groups have no effect on blood clotting using investigation of PT and APTT. The reason why these two parameters were significantly increased in PCL and PBW samples compared to the control samples is probably due to the attachment of some proteins from the serum to the surface of the samples38. The interaction between these serum proteins and sample surfaces could potentially alter the kinetics of the clotting process, thereby leading to prolonged clotting times in these specific groups. Further investigation into the nature of these protein surface interactions may provide further insight into the underlying mechanisms affecting coagulation in this context.

Examining the amount of released hemoglobin in blood samples incubated with different composite groups showed the hemolysis rate of the samples (Figure S2C). The hemolysis rate of the samples was less than 0.5%, which was less than the critical limit (5%) according to ASTM E2524-0839, indicating that the composite samples did not cause hemolysis in all groups.

SEM electron images of the composite samples (Control (+): PRP without any agents, NC and PBW) after the process of incubation in PRP, washing and stabilization, were shown in Figure S2D, E, and F. According to the control (+) which was washed and stabilized platelets in the size of about 1–3 µM, there was no activated platelet adhesion on the sample surface. In the NC, inactive platelets are trapped in the fibrous spaces and TPs, but their dimensions are small (≤ 1 μm) and not activated.

Investigation of cytotoxicity

An indirect method was first used to investigate the cytotoxicity of different groups (control without sample, NC, TPN, PCL, and PBW). The results of this study on two cell lines HUVEC and L929 were shown in Fig. 6A and B. Cell viability remained unchanged after incubating the samples in culture medium for 24, 48, and 72 h, indicating no significant difference from the control group. In the direct method in Fig. 6C, the cell viability of the NC and control had no significant difference. Scaffolds made of biocompatible materials behave like cellular matrices creating a suitable environment for cell growth40. In general, the L929 cell line is well established and has been used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of biomaterials41. Therefore, we used this cell line to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the composite. However, the cell viability of more than 70% in this category confirmed the non-toxicity of the material according to the ISO norm and indicated the non-toxicity of the NC42.

Cell viability (%) of (A) HUVEC cells in three conditions of 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation for the composite extraction and the cell viability (%) of (B) L929 cells in the three conditions of 24, 48 and 72 h of incubation for the composite extraction (indirect cell viability data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 4), (C) the cell viability (%) of L929 and HUVEC cells in 48 h of incubation for composite by direct method (direct cell viability data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 3), (D) light microscopic image of HUVEC cells on the bottom of cell culture plate (control), (E) SEM image of attachment of HUVEC cells on the NC with the scale bar of 50 μm, (F) quantitative analysis of DAPI intensity for NC and control group by measure the RGB ratio of blue color (B/(R + G + B)), DAPI staining images related to the attachment of HUVEC cells on the sample after 48 h of cell culture for (G) bottom of cell culture plate (control) and for (H) NC surface. Data points were analyzed by two-way and one-way ANOVA test (Tukey’s multiple comparison method) and the ns used as non-significant (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the differences between all groups and the control group in (A–C) at each time were not significant. In (C), the difference between L929 and HUVEC cell viability was not significant.

The attachment of HUVEC cells on NC

The incidence of HUVEC cell attachment on different surfaces of cardiovascular stents is of fundamental importance43. light microscopic image of HUVEC cells on the bottom of cell culture plate (control) was shown in Fig. 6D. The SEM image of the NC in Fig. 6E (with scale bars 50 μm) show the adhesion of the cells on the NC surface. Cells were observed to be oriented along the lines of PBW fibers. Cell elongation on NC is more noticeable than in control. The degree of endothelial cell attachment to the surface is considered one of the most important and vital variables in stent design. Surface endothelialization reduces the incidence of arterial stenosis and inflammatory response. DAPI staining was used to show the attachment of HUVEC cells to the surface of the NC and to the bottom of the cell culture dish as a control. Quantitative analysis (Fig. 6F) of DAPI intensity was done in control (Fig. 6G) and NC (Fig. 6H) groups by measuring the blue RGB ratio (B/(R + G + B)). The difference between NC and control was not significant. ImageJ software was used for obtaining the RGB values.

Investigating the degradation of samples in PRP

Platelets have lysosomes in addition to alpha and delta-granules, therefore we used of PRP for degradation44. To evaluate the degradation of NC and PBW in PRP, the samples were incubated in PRP for 24 h, then washed (Four times) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were subsequently obtained. Figure 7A shows the NC (nanofiber composite) before incubation, while Fig. 7B shows the NC after incubation. The most important finding in these figures is the change in surface morphology and the disappearance of the gap between the nanofibers. Figure 7C shows the PBW nanofibers before incubation, while Fig. 7D shows the PBW after incubation in PRP. From these images, we can see that the nanofibers have merged, leading to an increase in the nanofiber size. These changes may result from the enzymatic degradation of materials by lysosomes.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images illustrating the degradation of nanocomposites (NC) and PCL with BW (PBW) after incubation in platelet-rich plasma (PRP). (A) NC before incubation shows distinct nanofiber spacing. (B) NC after 24 h in PRP exhibits altered surface morphology and a notable disappearance of the gaps between nanofibers. (C) PBW nanofibers before incubation display a uniform arrangement. (D) PBW after 24 h in PRP reveals merging of nanofibers, resulting in an increase in overall nanofiber size.

The 3D stent design evaluation

Detailed information about the mesh design stent is presented in Fig. 8A. The dimensions of each component are as follows: the length of the closed diamond with a larger diameter measure between 3.5 and 3.8 mm, while the smaller diameter in its closed form is approximately 0.3 mm. The width of the band between each diamond is about 0.6–0.65 mm. The length of the stent consists of three diamonds, each measuring approximately 16–17 mm, and the width of the stent features four closed diamonds. For comparison, the degradation rate of the 3D-printed surface modified sulfated chitosan-PCL stent 24 was 16 and 7% with and without lysozyme after 60 days, considering its 3 mm diameter and 10 mm length. In another studies on stents where PCL polymer was considered specifically for 3D printing with a radial compression of 0.56 ± 0.11 N/mm (radial compression of the present study was calculated between 0.56 and 0.57 N/mm). Large size (15 mm long and 5.5 mm nominal diameter) with strut width (350 μm) for application of flow-diverting in endovascular treatment of aneurysms45. Furthermore, the radial compression in comparison to sulfated chitosan-PCL and PCL polymer (about 0.36 N/mm)24 was improved.

The schematic of (A) mesh design in 2D format, (B) the constructing of stent for balloon expansion usage, (C) the stent fabricated on the closed balloon with a diameter of 2.3 ± 0.07 mm, (D) stent opened with a balloon up to a diameter of about 3.56 ± 0.04 mm, (E) and then stent closure approximately 2.42 ± 0.05 mm of diameter with balloon deflation, (F) remaining the stent in the open state (diameter of 3.43 ± 0.2 mm) by removing the balloon pressure after being placed in the aqueous environment at T = 37 ºC for 30 s, (Data are presented as mean ± SD for n = 6)

In another application, where the polyethylene glycol (PEG) was added to PCL, a simple coil design for a thermosensitive shape memory drug-eluting stent was used with good biocompatibility. The degradation rate in the optimal state was achieved at about 47% after 60 days and the ultimate tensile strength was about 1.1 ± 0.35 MPa46. The degradation rate of PCL or PCL/PLA alone is very low47, and it is best combined with hydrophilic polymers. Synthetic polymers have favorable mechanical properties, but due to their low degradation rate and biocompatibility, they have weaknesses compared to naturally derived materials. In this study, the combination of PCL, a synthetic polymer, and natural hydrophilic TP was investigated for the first time as a stent body. To fabricate the stent body and its application on the angioplasty balloon, a specific mesh design was created using CO2 laser cutting. Research has been conducted on the application of fiber laser cutting method for PCL sheets48.

The schematic of the stent, featuring a closed structure and an open shape upon balloon expansion, is shown in Fig. 8B. In this design model (Fig. 8C), the stent is cut into a cylinder with a diameter of 1.9 to 2 mm (on a closed balloon with a diameter of 2.3 ± 0.07). This stent can be expanded to a diameter of 3.56 ± 0.04 mm on a balloon (Fig. 8D). The balloon pressure was then removed and the stent was closed to a diameter of approximately 2.42 ± 0.05 mm (Fig. 8E). To check and ensure that the stent remained open by removing balloon pressure, the stent was placed in a water environment at 37 ºC for 30 s and the same open state was maintained by absorbs water into its structure (diameter of 3.43 ± 0.2 mm) (Fig. 8F). Acute stent recoil (insufficient stent expansion and reduction of final stent surface area) is an important factor in stent design to avoid clinical events and restenosis 11. The achieved recoil ratio is about 3 to 4% and the recoil ratio of this stent improved in comparison to PCL as synthetic polymer (9–30%) 47 and when using balloon angioplasty needs to be evaluated in the future in an animal model. The Young’s modulus obtained from the presented stent (227 ± 19 MPa) compared with other works was obtained lower than pure PCL 47 but was obtained more than PEG/PCL 46.

Conclusion

The objective of this study was to generate a three-dimensional stent structure with balloon-expandable properties for use in cardiovascular stents. The body of the stent was composed of biodegradable NC based on PCL polymer and thermoplastic of oxidized starch TPN. The use of starch increased the rate of structure degradation due to water absorption. This improved the mechanical properties of the stent and increased the Young’s modulus and tensile strength of the electrospun PCL. This was also a very important factor in the balloon expansion of the stent. The stability of starch in an aqueous environment has been a very important factor when using starch as a material for cardiovascular stents. Therefore, the oxidation in the vicinity of iron oxide nanoparticles improved the structure of starch and increased its stability. This process facilitated the formation of functional groups, specifically carboxyl and carbonyl groups, which interacted with the Fe3O4 nanoparticles. As a result, the stability of starch in water was greatly improved. Based on the studies conducted on the stability of the stent and its degradation, it can be stated that the stent had a suitable degradation rate while maintaining structural integrity. Cytotoxicity results in HUVEC and L929 cell lines were also reasonable. Blood compatibility testing also confirmed that this NC was used according to suitable standards for vascular stents. Therefore, this structure can be used as a new design cardiovascular stent. One of the most important limitations of this type of stent was its radial strength after degradation when used as a stent in vascular occlusion. Note that this resistance is not completely eliminated after balloon expansion and its mechanical properties gradually decrease. The main purposes of using oxidized starch in the stent body are:

-

Mechanical property enhancement: oxidized starch is incorporated to improve the mechanical properties of polycaprolactone (PCL), making the stent more durable and resilient.

-

Adhesion aid: oxidized starch plays a critical role in facilitating the adhesion between layers of the multi-layer nanocomposite sheets during the hybridization process. This helps in creating a stable and cohesive structure.

-

Green material usage: as a natural polymer, oxidized starch serves as an environmentally friendly material in the composite, aligning with the increasing demand for sustainable biomedical materials.

-

Structural integrity maintenance: the oxidized starch contributes to maintaining the structural integrity of the stent during its gradual degradation, ensuring it remains functional throughout its intended lifespan.

Overall, the incorporation of oxidized starch is pivotal for achieving a composite material that is effective for vascular stent applications, due to its mechanical, adhesive, and biocompatibility properties.

Data availability

Data is available in the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Martin, D. M. & Boyle, F. J. Drug-eluting stents for coronary artery disease: a review. Med. Eng. Phys. 33(2):148–163 .

Ahadi, F. et al. Evaluation of coronary stents: a review of types, materials, processing techniques, design, and problems. Heliyon 9 (2), e13575 (2023).

Alam, S. T. et al. A review based on biodegradable and Bioabsorbable stents for Coronary Artery Disease. Procedia Comput. Sci. 152, 354–359 (2019).

Novitzke, J. A patient guide to brain stent placement. J. Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2 (2), 177–179 (2009).

Mittal, B. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases in coronary artery disease. Adv. Clin. Chem. 64, 1–72 (2014).

Lee, D. H. & de la Hernandez, J. M. The newest generation of drug-eluting stents and Beyond. Eur. Cardiol. 13 (1), 54–59 (2018).

Asti, A. & Gioglio, L. Natural and synthetic biodegradable polymers: different scaffolds for cell expansion and tissue formation. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 37 (3), 187–205 (2014).

Guerra, A. J. & Ciurana, J. 3D-printed bioabsordable polycaprolactone stent: The effect of process parameters on its physical features. Mater. Des. 137, 430–437. (2018).

Guerra, A. J., San, J. & Ciurana, J. Fabrication of PCL/PLA Composite Tube for Stent Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP. 65, 231–235 (2017).

Atari, M., Labbaf, S. & Javanmard, S. H. Fabrication and characterization of a 3D scaffold based on elastomeric poly-glycerol Sebacate Polymer for heart valve applications. J. Manuf. Process. 102, 350–364 (2023).

Abhyankar, A. D. & Thakkar, A. S. In vivo assessment of stent recoil of biodegradable polymer-coated cobalt-chromium sirolimus-eluting coronary stent system. Indian Heart J. 64 (6), 541–546 (2012).

Shi, S. et al. An innovative solvent-responsive coiling–expanding stent. Adv. Mater. 33 (32), 2101005 (2021).

Homaeigohar, S. & Boccaccini, A. R. Nature-Derived and Synthetic Additives to poly(ɛ-Caprolactone) Nanofibrous Systems for Biomedicine; an Updated Overview. Front. Chem.. 9 (2022).

Ghavimi, A. A. Polycaprolactone/starch composite: fabrication, structure, properties, and applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 103 (7), 2482–2498 (2015).

Oyeyemi Fabunmi, O. et al. Developing Biodegradable Plastics from starch. (2007).

Zdrahala, R. J. Thermoplastic starch revisited. Structure/property relationship for dialed-in biodegradability. Macromol. Symp. 123 (1), 113–121 (1997).

Hataminia, F. et al. Green synthesis of oxidized starch with a novel catalyst based on Fe3O4 nanoparticles and H2O2 reagent to form thermoplastic as a stable gel coating on the cardiovascular stents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. (2022).

Nevoralová, M. et al. Structure characterization and Biodegradation Rate of Poly(ε-caprolactone)/Starch blends. Front. Mater. 7. (2020).

Averous, L. et al. Properties of thermoplastic blends: starch–polycaprolactone. Polymer 41 (11), 4157–4167 (2000).

Jukola, H. et al. Electrospun Starch-Polycaprolactone Nanofiber‐based constructs for tissue Engineering. AIP Conf. Proc. 973 (1), 971–974 (2008).

Komur, B. et al. Starch/PCL composite nanofibers by co-axial electrospinning technique for biomedical applications. Biomed. Eng. 16 (1), 40 (2017).

Mahdavi, M. et al. Synthesis, surface modification and characterisation of biocompatible magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Molecules 18 (7), 7533–7548 (2013).

Tolvanen, P. et al. Oxidation of starch by H2O2 in the Presence of Iron Tetrasulfophthalocyanine Catalyst: the Effect of Catalyst Concentration, pH, solid–liquid ratio, and origin of Starch. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52 (27), 9351–9358 (2013).

Qiu, T. et al. Development of 3D-Printed Sulfated Chitosan Modified Bioabsorbable stents for Coronary Artery Disease. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8. (2020).

Robinson, M. R. et al. As(V) and as(III) sequestration by starch functionalized magnetite nanoparticles: influence of the synthesis route onto the trapping efficiency. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 21 (1), 524–539 (2020).

Moreira, G. F. et al. XPS study on the mechanism of starch-hematite surface chemical complexation. Miner. Eng. 110, 96–103 (2017).

Chiu, N. F. et al. Immunoassay-Amplified Responses Using a Functionalized MoS 2 -Based SPR Biosensor to Detect PAPP-A2 in Maternal Serum Samples to Screen for Fetal Down’s Syndrome. Int. J. Nanomed. 16. (2021).

Capelli, S., Motta, D. & Evangelisti, C. Effect of Carbon Support, Capping Agent amount, and pd NPs size for Bio-adipic Acid production from Muconic Acid and Sodium Muconate. 10(3). (2020).

Passaretti, M. et al. Biocomposites based on Thermoplastic Starch and Granite Sand Quarry Waste. J. Renew. Mater. 7, 393–402 (2019).

del Angel, K. et al. Development, fabrication, and characterization of Composite Polycaprolactone membranes Reinforced with TiO2 nanoparticles. Polymers 11, 1955 (2019).

Li, C. et al. A numerical solution to the effects of surface roughness on water–coal contact angle. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 459. (2021).

Hekmati, A. H. et al. Effect of nanofiber diameter on water absorption properties and pore size of polyamide-6 electrospun nanoweb. Text. Res. J. 84 (19), 2045–2055 (2014).

Husseinsyah, S. & Ahmad, R. Properties of low-density polyethylene/palm kernel shell composites: Effect of polyethylene co-acrylic acid. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 26. (2013).

Schlumberger, C. et al. Reliable surface area determination of powders and meso/macroporous materials: small-angle X-ray scattering and gas physisorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 329, 111554 (2022).

Sonseca, Á., Menes, O. & Giménez, E. A comparative study of the mechanical, shape-memory, and degradation properties of poly(lactic acid) nanofiber and cellulose nanocrystal reinforced poly(mannitol sebacate) nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 7 (35), 21869–21882 (2017).

Archer, E., Torretti, M. & Madbouly, S. Biodegradable polycaprolactone (PCL) based polymer and composites. Phys. Sci. Rev. (2021).

Hackett, J. et al. Electrospun Biocomposite Polycaprolactone/Collagen Tubes as scaffolds for neural stem cell differentiation. Materials 3. (2010).

Nelson Sathy, B. et al. Role of Nanofibrous Poly(Caprolactone) Scaffolds in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Attachment and Spreading for In Vitro Bone Tissue Engineering—Response to Osteogenic Regulators. Tissue Eng. Part A. 16, 393–404. (2009).

Choi, J. et al. Physicochemical characterization and in Vitro Hemolysis Evaluation of Silver Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Sci. 123 (1), 133–143 (2011).

Helen, W. & Gough, J. E. Cell viability, proliferation and extracellular matrix production of human annulus fibrosus cells cultured within PDLLA/Bioglass composite foam scaffolds in vitro. Acta Biomater. 4 (2), 230–243 (2008).

Nasseri, E. B. & Eskandarizadeh, A. Comparative study of different cytotoxicity of bonding systems with different dentin thickness on L929 cell line: an experimental study. Dent. Res. J. 17 (6), 424–432 (2020).

Srivastava, G. K. et al. Comparison between direct contact and extract exposure methods for PFO cytotoxicity evaluation. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 1425 (2018).

Wang, G. X. et al. The adhesive properties of endothelial cells on endovascular stent coated by substrates of poly-l-lysine and fibronectin. Artif. Cells Blood Substit. Immobil. Biotechnol. 34 (1), 11–25 (2006).

Ciferri, S. et al. Platelets release their lysosomal content in vivo in humans upon activation. Thromb. Haemost. 83 (1), 157–164 (2000).

Tidwell, K., Harriet, S. & Barot, V. Des. Anal. Biodegradable Polycaprolactone Flow. Diverting Stent Brain Aneurysms. 8(11). (2021).

Yang, C. S. et al. Thermo-Induced shape-memory PEG-PCL copolymer as a dual-drug-eluting biodegradable stent. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 5 (21), 10985–10994 (2013).

Guerra, A. J. et al. 3D-Printed PCL/PLA Composite stents: towards a New Solution to Cardiovascular problems. Materials 11 (9), 1679 (2018).

Guerra, A., Farjas, J. & Ciurana, J. Fibre laser cutting of polycaprolactone sheet for stents manufacturing: a feasibility study. Opt. Laser Technol. 95, 113–123 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Tehran University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support (grant number: 98-01-87-42142) and Research Center for Advanced Technologies in Cardiovascular Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (grant number: 1401-3-489-62953) for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.H. contributed to the project by conceptualizing the idea, developing the methodology, and writing the original draft. H.Gh. assisted with data curation, conducted investigations, validated the findings, and contributed to the writing through review and editing. R.ّّّF was responsible for visualization, as well as investigation and validation of the research. S.M.A.H. contributed to the validation and methodology aspects of the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The ethical approval was obtained from National Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences with ethical number of IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.184. informed consent obtained from all subjects and legal guardians. The privacy rights of human subjects always be observed and all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hataminia, F., Faridi-Majidi, R., Hashemi, S.M.A. et al. Fabrication of a multilayer bioabsorbable composite vascular stent utilizing oxidized starch-Fe3O4 nanoparticles and polycaprolactone nanofibers. Sci Rep 15, 7454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86111-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86111-x