Abstract

Genetic factors play a significant role in the occurrence and clinical course of diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). This research aimed to search the influence of adiponectin single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on the risk of developing and the severity of DPN in Egyptian patients. Adiponectin SNPs were genotype in 360 participants comprising diabetic sufferers with and without peripheral neuropathy and healthy volunteers via the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) approach. Regarding the + 45 T/G SNP, the TG/ and GG genotypes and the G allele were linked to an rised risk of DPN by comparing the DPN group with both the control and diabetic patients without peripheral neuropathy (DWPN) groups, and when comparing the DWPN group with the control group. Concerning + 276 G/T SNP, the GT genotype and T allele were linked to a declined risk of occuring DPN when comparing the DPN group with both other groups. Patients with DPN had greater frequencies of the GA genotype of the − 11,391 G/A SNP than individuals in the control group, while patients with DPN had greater frequencies of the AA genotype than patients in the DWPN group. Regarding clinic-pathological features, a meaningful rise in the mean values of fasting blood glucose (FBG), duration of the disease, and Toronto Clinical Neuropathy Severity Score (TCSS) were noted in the + 45 GG genotype and G allele carriers. Contrariwise, the + 276 TT genotype carriers had lower mean values for the same clinic-pathological features. For the T allele carriers, the same results were observed in case of duration of the disease and TCSS value. Our results concluded that adiponectin + 45 T/G SNP could be a risk factor considering DPN and the severity of the disease. The − 11391G/A SNP might be associated with DPN. In addition, + 276 G/T SNP could be a protective factor regarding DPN and the severity of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is the ninth prominent and principle reason of death in the past 30 years. It occurs due to either resistance to insulin action, insulin secretion, or both1,2. Globally, about 9.3% of adults currently have diabetes, and the prevalence will increase to 10.2% and 10.9% by 2030 and 20453,4. In Egypt, T2DM affects roughly 15.56% of adults, with a corresponding yearly mortality rate of about 86,478, and it is expected that the prevalence of diabetes will be increased to 13.1 million by 20355. DM is a complicated contact of systemic metabolic abnormalities like chronic hyperglycemia, local tissue reactions to toxic and harmful metabolites and dyslipidemia, which tends to trigger several macro- and microvascular complications leading to severe morbidities like nephropathy retinopathy, and neuropathy6.

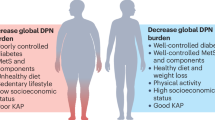

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is among the greatest and widespread frequent, distressing, and earliest chronic microvascular complications of diabetes and affects various periphery nerve systems comprising motor and sensory neurons, causing considerable disability and poor quality of life7,8. It is often asymptomatic throughout its early stages; nevertheless, once symptoms and obvious deficits have been established, it cannot be reversed9. Consequently, early diagnosis and timely mediation are essential to stop its development and progression. Several factors comprising diabetes duration, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) level, smoking, and gender, along with genetic factors, might influence the onset and the course of the disease7,10,11. One of the attractive candidates related to a susceptibility region for T2DM, traits related to diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease is adiponectin12,13,14,15. Adiponectin is a protein hormone derived from adipocytes with a molecular weight of 30 kDa12,16. It may exert several vasculoprotective effects, including its special pleiotropic influences on endothelial cells, endothelial progenitor cells, smooth muscle cells and macrophages17. Moreover, it plays a critical role in protecting versus inflammation through the macrophages polarization directly towards anti-inflammatory phenotype, resulting in the healing of wound and the resolution of inflammatory events18. Besides, it modulates the inflammatory response of endothelial cells by decreasing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) production and stopping vascular remodeling via blocking smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration of19. In addition, it promotes the p38 mitogen-activated protein family of kinases (p38MAPK) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and signaling pathways; thus, decreasing its plasma levels may interfere with the primary functioning of these essential pathways, inducing the development of diabetic phenotype20,21. Moreover, its low plasma levels changed lipid regulation causing Schwann cells collecting fat metabolites, which affects functions of peripheral nerve in diabetic sufferers22. Furthermore, abnormal levels of serum adiponectin are related to T2DM, obesity, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), insulin resistance, nephropathy, and neuropathy23,24. The adiponectin gene, which harbors three exons and two introns, is mapped on chromosome 3q2725. Numerous important single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the gene of adiponectin are significantly correlated to the pathogenesis of diabetes16,26. The SNPs to be investigated were chosen according to the following criteria: proved SNPs for frequency in Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS), and SNPs with scientific proof for their role in increased protein synthesis. Prior Studies have interested mostly on three SNPs, that were amongest the primary to be investigated via specialized resequencing attempts27. the gene’s immediate five flanking region contains − 11391G/ A (rs17300539), while exon 2 and intron 2 include + 45T/G (rs2241766), and + 276G/T (rs1501299), respectively28.

Although restricted prior studies investigated the linkage between the aforementioned adiponectin SNPs and the DPN risk29,30,31, the available inadequate documents and the unpredictable outcomes from these reports encouraged us toward considering a systematic and regular investigation of the adiponectin SNPs for their impact on the risk of DPN in T2DM patients. Thus, the current study aimed to obtain dependable approach to distinguish T2DM cases at high risk for DPN from others at low risk by determining the association of adiponectin SNPs, including + 45 T/G (rs2241766), + 276 G/T (rs1501299), and − 11,391 G/A (rs17300539) with the risk of DPN in our Egyptian patients. Moreover, the study examined SNPs’ prognostic significance in DPN sufferers by analyzing how they correlate with clinico-pathological features and disease severity.

Subjects and methods

Subjects design and description

The present case-control study involved 360 participants who were categorized into two groups: Group I consisted of 240 patients suffering from T2DM, which sub-grouped into 120 diabetic patients with peripheral neuropathy (DPN) and 120 diabetic patients without peripheral neuropathy (DWPN), and Group IIincluded 120 apparently healthy individuals. Cases and healthy controls were recruited from the patients attending the outpatient diabetic clinic of Zagazig University Hospital, Internal Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt from December 2021 to February 2023. The research ethical approval (reference number: ZU-IRB #9623/5-1-2022) was obtained by the Ethical Committee and the International Review Board (IRB), Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, and all procedures respected to the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical rules. Written informed agree and consent was taken from all subjects shared in this study. The diagnosis of the disease was done followed the American Diabetes Association (ADA) criteria32 and aged between 30 and 50 years ago. The exclusion standards comprised the existence of autonomic or peripheral neuropathies from reasons other than diabetes, severe comorbidities (such as, recent cardiovascular events, heart failure, malignancies, and liver disease or advanced renal failure), and advanced peripheral arterial disease. In addition, patients receiving long-term immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy, those with Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), those taking insulin, smokers, and those with hypertension were excluded from the research. Healthy subjects as a control group were randomly recruited from the general puplic at the same time. The collection of the complete personal information [such as age, gender, diabetes, and hypertension], a clinical examination [including comorbidity, blood pressure (BP), and blood glucose at the moment of neurological assessment], and anthropometric measurements [weight (kilograms), height (meters), and body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and disease duration] were done by the direct contact with all contributors and from the outpatient medical files. Regular and routine clinical-laboratory data as fasting blood glucose (FBG), lipid profile, and hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c) were collected from medical record sheet.

Diabetic polyneuropathy assessment

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy was evaluated by neurological examination and nerve conduction study (NCS) of upper and lower limbs and a combined clinical and electrophysiological score. NCS was reflected the abnormality if the abnormality value was ≥ 1 in two separate nerves33. Grouping of patients based on DPN was as follows: cases with no electrophysiological or clinical confirmation of neuropathy were characterized as normal, those with clinical signs or indications of neuropathy were characterized as probable clinical DPN, those with a mixture of clinical signs and indications of neuropathy were characterized as possible clinical DPN, those with abnormal NCS but without clinical signs nor indications of neuropathy were characterized as subclinical DPN, and those with a mixture of clinical signs and indications in addition to abnormal NCS was characterized as confirmed DPN.

The Toronto Clinical Scoring System (TCSS) was employed to monitor the severity DPN according to symptoms, reflexes, and sensory testing findings34,35. According to the TCSS score, the neuropathy was classified into 0–5 (indicating no neuropathy), 6–8 (indicating mild neuropathy), 9–11 (indicating moderate neuropathy), and 12 (indicating severe neuropathy).

Methods

SNP selection

These SNPs were chosen based on their established associations with adiponectin function and their potential relevance to diabetic complications including DPN according to previous studies31,36,37,38. The primer sequences and restriction enzymes for examining of each SNP were examined based on the free, on-line (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), and (https://nc2.neb.com/NEBcutter2/?noredir) version 2.0, respetively.

Extraction of genomic DNA

By using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Cat-No: #51104; Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA), DNA from the genome was isolated from EDTA- blood samples as defined by the manufacturer’s instructions. A NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND1000; NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, Delaware, USA) and a 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis were employed to assess the concentration and quality of DNA, respectively, and stored and frozen at −80oC until use.

Genotyping of adiponectin + 45 T/G (rs2241766), + 276 G/T (rs1501299), and − 11,391 G/A (rs17300539) SNPs

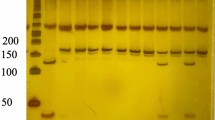

All SNPs were genotyped using the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) method by using the following primers: for + 45 T/G (rs2241766), F: 5̀-GAAGTAGACTCTGCTGAGATGG-3̀ and R: 5̀-TATCAGTGTAGGAGGTCTGTGATG-3̀, for + 276 G/T (rs1501299), F: 5̀-TCTCTCCATGGCTGACAGTG-3̀ and R: 5̀-AGATGCAGCAAAGCCAAAGT-3̀ (38), and for − 11,391 G/A (rs17300539), F: 5̀-TTGGATGTCTTGTTGAAG-3̀ and R: 5̀TTTCGGATAACATTTTGACAGC-3̀ (36). SNPs’ PCR reactions were carried out in 20 µL of 10 µL Master Mix specific to PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA), 1.5 µL of both primers (forward and reverse 10 pmol/µL), 4.5µL sterile deionized water, and 2.5µL of template DNA to produce the amplified PCR products.

To amplify PCR products, SNPs’ PCR reactions were conducted in 20 µL (1.5 µL of forward and reverse primers [10 pmol/µL], 10 µL Master Mix [Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA], 4.5 µL deionised water, and 2.5 µL of template DNA) in a thermal cycler (Biometra, Gottingen, Germany) as follows: initial denaturation at 94oC for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94oC for 30 s, (51oC for 30 s (for + 45T/G SNP), 52oC for 30 s (For + 276 G/T SNP) and 50oC for 30 s (for − 11391 G/A SNP)), and 72oC for 30 s, and a final extension of 7 min at 72oC. By using good quality FastDigest SmaI, BsmI, and MspI restriction enzymes(New England Biolabs, Massachusetts, USA) for 15 min at 37oC, the amplified PCR products were processed producing particulr fragments. In a gel documentation system (BioDocAnalyze, Biometra, Gottingen, Germany), the particular fragments were envisioned under UV light after being separated on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Statistical analysis

The computional SPSS software (version 20; IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was employed for the data analysis. The sample size was calculated according to the statistical method by using the online, Web-based, free, open-source program OpenEpi calculator version 3.01 (OpenEpi, n.d.). At 80% study power and 95% CI to find differences at the α-level of 0.05, the estimated sample will be 120 subjects per group, by calculation of CramerV for calculation of effect size effect size = 0.65. Quantitative data outcomes were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The outcomes of qualitative data were presented as numbers and percentages (N %). By applying the ANOVA test for quantitative variables, the variances in demographical data and laboratory parameters were compared between groups. The relationship between the genotype, allele, and the risk of diabetic polyneuropathy was examined via odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). ANOVA (F test) was used for comparison the means of several groups. Tukey’s test was employed for comparison in between groups. Chi-squared test was employed to find the association between categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was employed to find factors predicting the disease severity. The analysis of haplotype was applied via the Phase program39. The P value of 0.05 for all tests was reflected the significance.

Results

Demographical and clinico-laboratory data of studied groups

Table 1 includes the demographical and clinico-laboratory data of all studied groups. All three studied groups were matched regarding age and gender (P > 0.05). A significant difference was observed in all clinico-laboratory data when comparing diabetic patients with polyneuropathy with others (P < 0.001). Additionally, the same statistically significant difference was observed between the DWPN group and the control group (P < 0.001) apart from BMI and TG (P > 0.05). The mean duration of T2DM was highly significant in the DPN group when compared with the DWPN group (P < 0.001).

Genotype and allele frequencies of adiponectin SNPs in all studied groups

Adiponectin SNPs in the DPN group and control group

Successful amplification of the adiponectin + 45 T/G (rs2241766), + 276 G/T (rs1501299), and − 11391 G/A (rs17300539) SNPs was demonstrated by the presence of PCR amplified products with sizes of 372 bp (bp), 468 bp, and 356 bp, respectively (Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Regarding + 45 T/G (rs2241766) SNP, after digestion by restriction enzyme, the PCR-RFLP results were TT wild type homozygous (undigested product) (372 bp), TG heterozygous (372 bp, 219 bp, and 153 bp), and GG mutant homozygous (219 bp and 153 bp) (Fig. 4). In the case of + 276 G/T (rs1501299) SNP, GG wild type homozygous (digested fragment) (320 bp, 148 bp), GT heterozygous (468 bp, 320 bp, and 148 bp), and TT mutant homozygous (468 bp) were observed (Fig. 5). Concerning − 11391 G/A (rs17300539) SNP, GG genotype (266 bp, 90 bp), GA genotype (356 bp, 266 bp, and 90 bp), and AA genotype (356 bp) were detected (Fig. 6). According to Table 2, in the case of + 45 T/G SNP, the DPN group showed greater frequencies of TG and GG genotypes and G allele than in control group (56.7% vs. 31.7%, 31.7 vs. 15%, and 60% vs. 30.8%, respectively). In comparison to the TT genotype and T allele, the TG and GG genotypes and G allele were substantially linked to increased risk of developing DPN [odd ratios (ORs) (95% confidence intervals (CIs)a: 8.18 (2.76–25.1), P1 < 0.001; 9.65 (2.72–36.1), P1 < 0.001 and 3.36 (1.95–5.95), P1 < 0.001, respectively]. The GT genotype and T allele of + 276 G/T SNP were less frequent in the DPN group than in the control group (8.3% vs. 35% and 10.8% vs. 25.8%, respectively). Hence, the GT genotype and T allele were significantly linked to decreased risk of developing DPN as compared to the GG genotype and G allele [ORs (95% CIs)a: 0.16 (0.05–0.5), P1 < 0.001; 0.35 (0.16–0.74), P1 = −0.002, respectively]. The frequency of GA genotype and A allele of −11391 G/A SNP were higher in the DPN group when compared to the control group (55% vs. 36.7% and 44.2% vs. 30%, respectively). Hence, the GA genotype and A allele were considerably linked to a rised risk of occuring DPN as contrasted to the GG genotype and G allele [ORs (95% CIs)a: 2.74 (1.14–6.6), P1 = 0.012 and 1.85 (1.05–3.25), P1 = −0.02, respectively].

Adiponectin polymorphisms in DWPN and control group

The DWPN group had higher frequencies of + 45 GG genotype and G allele than the control group (31.7% vs. 15% and 46.7% vs. 30.8%, respectively). The GG genotype and G allele of + 45 T/G SNP were considerably related to a rising risk of occuring diabetes compared to the TT genotype and T allele [ORs (95% CIs)b: 2.94 (1.02–8.58), P2 = 0.02 and 1.96 (1.12–3.45), P2 = 0.01, respectively] (Table 3). When comparing the two groups, there are no significant differences in + 276 G/T and − 11,391 G/A SNPs.

Adiponectin polymorphisms in DPN and DWPN

Regarding + 45 T/G SNP, the DPN group had significantly higher frequencies of TG and GG genotypes and G allele than the DWPN group. The TG and GG genotypes [ORs (95% CIs)c: 6.2 (2.02–19.7) and 3.29 (1.02–10.95), P3 < 0.001 and P3 = 0.02, respectively] and the G allele [OR (95% CI)c: 1.71 (1–2.96)] were linked to a statistically significant upregulated risk of DPN when compared to the TT genotype and T allele. Concerning + 276 G/T SNP, GT heterozygous and T allele were associated with protection from developing DPN when comparing both groups [ORs (95% CIs)c: 0.12 (0.04–0.3), P3 < 0.001 and 0.26 (0.13–0.55), P3 < 0.001, respectively]. Moreover, the AA genotype of −11,391 G/A SNP was more frequent in the DPN group than in the DWPN group, and this indicated that this genotype was associated with increased risk of DPN in our cohort (OR (95% CI)c: 4.51 (0.95–24.6), P3 = 0.03).

Association between adiponectin SNPs and clinico-laboratory features in the DPN group

The numerous associations between the genotype frequencies of adiponectin gene SNPs and clinico-laboratory features in the DPN group are listed in Table 3. Regarding + 45 T/G SNP, at the genotypic level, a statistically significant increase in the mean values of FBG (P = 0.014), duration of the disease (P < 0.001), and TCSS [severity score] (P < 0.001) were noted in sufferes of GG genotype versus those of TT and TG genotypes. However, no significant relationship was found between different genotypes for other clinical data (P > 0.05). At the allelic level, a significant increase was observed in the disease duration (P = 0.04) and TCSS (P = 0.02) in G allele carriers when compared to T allele carriers. Inversely, the results revealed that patients with the mutant genotype (TT) had lower mean values for FBG (P = 0.04), disease duration (P = 0.013), and TCSS (P = 0.007) in the instance of the + 276 G/T SNP compared to those with the wild-type genotype (GG) and heterozygous genotype (GT). The same findings were observed at the allelic level, with a statistically significant decrease in the mean values of duration of the disease (P = 0.008) and TCSS (P = 0.002) in T allele carriers compared with G allele carriers. Regarding − 11,391 G/A SNP, only a statistically significant increase in the mean value of LDL cholesterol was observed in patients carrying the AA genotype (P < 0.001) and A allele (P < 0.001) compared to the GG genotype and G allele.

Haplotype analysis of adiponectin + 45 T/G and + 276 G/T SNPs in the DPN and DWPN groups

Haplotype analysis was performed on the DPN and DWPN groups (Table 4). The results exhibited that the G+45-T+276 and T+45-T+276 haplotypes were significantly associated with a decreased risk of polyneuropathy (OR = 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.79; P = 0.006, and OR = 0.39, 95% CI 0.15–0.97; P = 0.02, respectively), while the G+45-G+276 haplotype was linked to the higher risk of polyneuropathy (OR = 4.3, 95% CI 1.74–11.1; P < 0.001).

Haplotype analysis of adiponectin + 45 T/G and − 11,391 G/A SNPs in the DPN and DWPN groups

As presented in Table 5, the outcomes did not show any associations with polyneuropathy, except for the individuals carrying G+45-A−11391 haplotype was significantly linked to increased odd of polyneuropathy (OR = 2.1, 95% CI 0.95–4.67; P = 0.04).

Haplotype analysis of adiponectin + 276 G/T and − 11,391 G/A SNPs in the DPN and DWPN groups

In Table 6, the findings revealed that the T+276-A−11391 and T+276-G−11391 haplotypes were significantly associated with a decreased risk of polyneuropathy (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.17–0.99; P = 0.029, and OR = 0.2, 95% CI 0.08–0.52; P < 0.001, respectively) compared to diseased groups.

Multiple regression analysis for the disease severity prediction via TCSS

By applying multiple regression analysis, the disease duration, + 45 T/G, and − 11,391 G/A SNPs were recognized as predictors of increasing the severity of the disease according to their TCSS scores. Furthermore, + 276 G/T SNP was identified as a predictor of decreasing the severity of the disease as defined by their TCSS scores (Table 7).

Discussion

Chronic hyperglycemia, inflammation, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and genetic factors play a significant role in developing DPN40,41. Several studies have focused on SNPs − 11,377 C/ G (rs266729) and − 11391G / A (rs17300539) in the promoter area, + 45 T / G (rs 2241766) in exon 2, and + 276 G /T (rs1501299) in intron 2. These four polymorphic variants are situated within the two linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks of adiponectin: block 1, including the promoter sequence covering the area from − 14,811 to − 4120, and block 2, including the exons in the region − 450 to + 454537. Thus, the adiponectin + 45 T/G, + 276 G/T, and − 11,391 G/A SNPs were selected in this study to obtain better insights about the possible link between these SNPs and the hazard of developing DPN in Egyptian patients. Despite the increasing proof that polyneuropathy symptoms are not a dependable sign of neuropathy in the progression of the disease, around 50% of cases are asymptomatic; therefore, they are susceptible to unconscious foot problems39. Thus, early recognition of individuals at high risk is extremely important. To address this demand, the current study has investigated the association between the abovementioned SNPs in the adiponectin gene and our population’s risk of developing DPN. To be aware, limited documents have investigated the association between the aforementioned adiponectin SNPs and the risk of DPN before, and the results were hazy and unclear, this guided us to carry out this work on such relations in our Egyptian cohort.

Considering + 45 T/G (rs2241766) SNP, the DPN group showed greater TG and GG genotypes and G allele frequencies than the control and DWPN groups. The DWPN group exhibited higher frequencies of GG genotype and G allele than the control group. Thus, our results indicated that individuals carrying TG and GG genotypes and G alleles could be more susceptible to developing DPN in our population. Reinforcing our findings, Ji et al.29observed that the frequency of the GG genotype in the DPN group was significantly higher than in the normal control group and non-diabetic peripheral neuropathy (NDPN) group. On the contrary, no significant association was observed when comparing the NDPN and control groups. Likewise our results, Mohammadzadeh and Zarghami42 and Motawi et al.43 in Iranian and Egyptian studies, respectively, stated that TG/GG genotypes and the G allele of + 45 SNP occured more repeatedly than the TT genotype and T allele in T2DM patients compared to the control group (P < 0.05). In addition, Li et al.44 reported that the wild type + 45 GG genotype was associated with the increased risk of T2DM in Japanese population. In contrast to our results, Jr. et al.45 stated that no suggestion for the association between the + 45T/G polymorphism and diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, or nephropathy. Moreover, Hasani-Ranjbar et al.29 and Choe et al.30revealed that + 45 T/G SNP is not associated with diabetic neuropathy. One possible clarification of our findings is that this silent mutation, a synonymous mutation in exon 2 near the exon-intron junction, does not modify the amino acids sequence (GGT→GGG, Glycine→Glycine), and might impact adiponectin gene expression and circulating concentration of adiponectin via its linkage disequilibrium with another polymorphism in one of the introns that causes destabilization of the pre-mRNA, results in declined mRNA levels, and finally the development of pathophysiological effect and elevating phenotypic variability (DPN risk in T2DM patients)37,46.

Prior studies noted that the + 276 G/T SNP could play a protective role in T2DM, diabetic nephropathy and coronary artery disease (CAD) in different populations with T2DM36,38,47. In addition, Hara et al. 2002 also stated that the the wild type + 276GG genotype of the adiponectin gene was related to T2DM in Japanese study. Consistent with these results, our findings suggested that the heterozygote GT genotype and the mutant (T allele) were less frequent in the DPN group than in the control and DWPN groups. Hence, the GT genotype and T allele were significantly linked to the decreased risk of developing DPN and could confer protection against DPN in our Egyptian population. In disagreement with our results, Ji et al.31 observed that + 276 G/T (rs1501299) SNP could dramatically increase the chance of developing DPN in T2DM patients. Moreover, Choe et al.30showed that this SNP is not significantly linked to diabetic neuropathy prevalence. In agreement with our results, considering T2DM patients, several other literatures also did not note any association in the Chinese Han population48,49,50. By contrast, several studies observed that + 276 SNP was associated with T2DM in different populations51,52,53,54. The exact mechanism of how + 276 G/T SNP may be a protective factor in DPN is not completely well-defined. Several studies may clarify the match between our results and prior research on patients with diabetic nephropathy. Flyvbjerg47 and Demir et al.55indicated that diabetic microvascular complications are described through structural and functional organ damage according to vascular system modifications, which influence the capillaries and arterioles in the retina, kidney, and nerves. These changes include the wall thickening of small blood vessels, which causes bleeding and protein leakage, and the narrowing of blood vessels which reduces blood flow and impairs oxygen flow throughout the body, causing tissue or organ damage that are highly sensitive to oxygen levels like retina, kidney, and nerve cells. Moreover, the major destructive factor that is contributed to the structural and functional changes in the retina, kidneys, nerves, and vessels in people with diabetes is hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia is an upregulation in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) with cytosolic NADPH oxidase and insufficiency in main antioxidants like reduced glutathione (GSH), which initially cause complications such as diabetic retinopathy (DR), diabetic nephropathy (DF), and diabetic neuropathy (DN)56,57,58,59. Genetically, the + 276 G/T SNP is an intronic mutation. However, there is a strong linkage disequilibrium and close association between this SNP and G90S missense mutation and other SNPs in the promoter region, respectively, representing that altering pre-mRNA splicing may cause downregulation of adiponectin expression60. In another words + 276 G/T is located distant from the common splice region inside intron 2 of the gene; with no well-known function. It may be an indicator of some other polymorphic modifications that influencing the gene expression. It has been observed that there was approximately complete linkage disequilibrium between this SNP and numerous genetic variations localized in the 3’ untranslated regions (3’UTR), which play a key function in the controlling of the gene expression via attaching proteins that control the processing, degradation or translation of mRNA60. Moreover, the mutant allele of this SNP (T allele) upregulated the plasma adiponectin levels and declined the insulin resistance61. Nevertheless, Kacso et al.62. observed that the TT genotype was associated with higher plasma adiponectin levels in T2DM patients. They speculated that although T2DM is characterized by “suppressed” adiponectin synthesis as reflected by lower adiponectin levels in T2DM patients in comparison to controls, diabetic carriers of the + 276 TT allele might be able to overcome this suppressed state in the presence of chronic inflammation that represents a characteristic of T2DM and a stimulus for adiponectin synthesis causing sufficiently increase in adiponectin levels. One interesting point is that diabetic patients carrying the T allele have better glycemic control than the other T2D subjects supporting a probable protective impact of this SNP. Moreover, another Spanish study reported that the adiponectin rs1501299 T allele upregulated plasma adiponectin levels and declined insulin resistance61.

Concerning − 11,391 G/A (rs17300539) SNP, the results showed that the frequencies of heterozygous GA genotype and mutated A allele were higher in the DPN group when compared to the control group. Moreover, the mutated AA genotype was more frequent in the DPN group than in the DWPN group, and this indicated that this SNP was associated with an increased risk of DPN development in our cohort. One study investigated the effect of this SNP on DPN risk in the Iranian population and reported the lack of association between the − 11,391 G/A SNP and diabetic microvascular complications, including neuropathy29. Our findings follow those reported by El-Shal et al.38 who reported that − 11,391 G/A SNP is associated with diabetic nephropathy in the Egyptian population. In addition, Hamza et al.63 revealed that − 1139 G/A SNP was associated with the diabetic nephropathy in Iraqi population from the middele Euphrates region. Regarding T2DM, Similar to our finding, Nomani et al.64 observed that − 11,391 G/ A SNP of adiponectin gene was not significantly linked to susceptibility to T2DM. Contrary to our outcomes, the conclusion of Vasseur et al.65 indicated that this SNP were significantly associated with T2DM in French Caucasian study. Moreover, Olckers et al.66noted that GA heterozygote in Black South African individuals with T2DM patients had a protective effect on the T2DM. Adiponectin − 11,391 G/A (rs17300539) polymorphism is situated in the intron 1. Although not portion of the promoter, it might be present on the sequence of enhancer. Sequences of enhancer could be situated in area of introns and as a result can modify the gene expression67. Furthermore, this SNP could provide otherwise spliced mRNA or influence the stability ofmRNA68.

In this study, to examine the prognostic value of these SNPs in DPN patients, their associations with clinico-laboratory features in the DPN group were evaluated. Furthermore, our study is the first to focus on the effect of these SNPs on TCSS [severity score] to validate the possible role of adiponectin SNPs on the disease severity.

Considering the laboratory parameters, for + 45 T/G SNP, a statistically significant upregulate in the FBG mean values and duration of the disease were demonstrated in GG carriers and G allele carriers (except FBG) compared to TT and TG carriers and T allele carriers, respectively. In agreement with our results, Momin et al.69 revealed a higher level of FBG in TG and GG carriers than in the wild type. However, conflicting with our results, they observed a significant association between + 45 T/G SNP and higher BMI and TG in type 2 diabetics. Moreover, Hussain et al.70 and Joshaghani et al.71observed the association between the G allele in the + 45T/G SNP and the BMI increase. However, Ji et al.31, opposing our results, demonstrated no significant association between this SNP and the duration of diabetes and FBS in Korean T2DM with cardiovascular complications. Nevertheless, following our results, they demonstrated no significant differences between the + 45 T/G polymorphism and BMI, HbA1c, TG, and LDL. In addition, Palit et al.14 recorded the association of the + 45 T/G SNP with increased FBG in Gujarat diabetic patients.

Regarding + 276 G/T SNP, a statistically significant decline in the FBG mean values and duration of the disease were demonstrated in sufferers carrying the mutant (TT) genotype and the T allele (except FBG) in comparison to those with the wild type genotype (GG) and heterozygous genotype (GT) and G allele, respectively. Our observations are similar to the findings of Shramko et al.72who stated that + 276 GG genotype carriers had higher blood glucose levels than GT and TT carriers in T2DM patients. Inversely, another study found an association between this SNP with an increased mean value of FBG in Gujarat diabetic patients14. Moreover, Al-Nbaheen73 observed that this SNP in the adiponectin gene in the Saudi population with T2DM has no impact on any of the included baseline parameters like FBG, HbA1c, and lipid profile parameters.

Concerning − 113,919 G/A SNP, our results showed no significant association between any of the clinical features of DPN patients and this SNP. Only the LDL mean value revealed a statistically significant upregulation in the AA genotype and A allele carriers in comparison to the GG genotype and G allele carriers. Opposing to our results, Tabatabaei-Malazy et al.74noted a significantly higher BMI in women, and GA or AA carriers of − 11391G/A polymorphism in diabetic subjects when compared to non-diabetic subjects in the south-east of Iran. One explanation of our results is that the effect of SNPs of adiponectin on FBG (in case of + 45 T/G and + 276 G/T SNPs) and on LDL cholesterol (in case of −113919G/A SNP) may be attributed to the effect of adiponectin on glucose and lipid metabolism70. In addition, no association between these SNP and several of the above clinic-laboratory parameters related to DPN was observed. It is reasonable to infer that the genetic effects of these SNPs on T2DM are induced through changed adiponectin expression that affects some of the metabolic parameters75. The metabolic parameters might be detected by numerous genetic and environmental factors or lifestyle interferences in several populations and sample sizes76.

Considering the TCSS score and the disease severity, no prior study considered the relationship between the adiponectin SNPs and the disease severity in DPN patients. Our results revealed a statistically significant increase in the mean value of TCSS in + 45GG carriers and + 45G allele carriers compared to + 45TG and + 45TT carriers and + 45T allele carriers, respectively. Moreover, a statistically significant downregulate in the mean value of TCSS was observed in mutant genotype + 276TT and + 276T allele compared to + 276GT, + 276GG, and + 276G allele, respectively. These results revealed that the mutated genotype and + 45 T/G SNP allele are associated with increased disease severity. Besides, the mutated genotype and + 276 G/T SNP allele are associated with decreased disease severity in our population. Our data indicated the possible pivotal role of these adiponectin SNPs in the determination of disease severity in order to predict the progression of the disease. In addition, multiple regression analysis was performed to confirm our results and further analyze the relationship between the clinico-laboratory features of the disease and the studied SNPs and the TCSS in the DPN group to recognize the predictive factors that might account for the disease severity. It indicated that the duration of the disease and the + 45 T/G and − 11,391 G/A SNPs were identified as high-risk factors for the disease severity in DPN patients’ TCSS scores. Additionally, + 276 G/T is protective in the disease severity. Agreeing with our results, Szopa et al. [36] noted that the T allele of + 276 G/T was a protective risk factor, whereas the A allele of −11.391G/A was a risk factor concerning T2DM in Polish Caucasian patients.

Based on the haplotype analysis, our findings showed that G+45-T+276 and T+45-T+276 haplotypes were significantly associated with a decreased risk of polyneuropathy when comparing DPN and DWPN groups. Nevertheless, the G+45-G+276 haplotype was significantly linked to a higher risk of DPN when comparing the same groups. Similarly, Szopa et al.36 stated that the T+45-T+276 haplotypes were less frequent in the T2DM group than in the control group. Esteghamati et al.77 observed the same results in coronary artery disease in Iranian patients with type 2 diabetes. Moreover, Ji et al.29 found that G+45-T+276 haplotypes are negatively linked to the risk of DPN compared to the DPN and control groups. A recent study by Joshaghan et al. showed that the + 45G/+276G haplotype was linked to the increased risk of T2D in the Iranian population.

On the contrary, the same authors observed that the G+45-G+276haplotype was negatively associated with the risk of DPN when comparing the same groups. One explanation is that the + 45 T/G and + 276G/T SNPs are in a linkage disequilibrium block28. Furthermore, the two SNPs may be in linkage disequilibrium with other functional genetic loci that modify adiponectin production or its polymerization capability, altering its biological activity. In the case of haplotype analysis of adiponectin + 45 T/G and − 11,391 G/A SNPs in the DPN and DWPN groups, the individuals carrying G+45-A−11391haplotype were significantly associated with an increased risk of polyneuropathy. Our results may be attributed to the presence of strong linkage disequilibrium between this SNP and other SNPs of adiponectin gene like − 11,377 and − 11,391 SNPs in the 5′ promoter region that affects the expression, structure, or action of adiponectin65. Moreover, for haplotype analysis of adiponectin + 276 G/T and − 11,391 G/A SNPs in both groups, T+276-A−11391 and T+276-G−11391 haplotypes were significantly associated with a decreased risk of polyneuropathy.

Our current study is exceptional because no previous study has investigated the association between the adiponectin SNPs and the disease severity in DPN patients. Nevertheless, this study has a few potential limitations that should be taken into consideration. The first one, we carried out our study on Egyptian population, thus outcomes may not be appropriate to all populations and all ethnicities. Secondly, the study design was presented as a cross-sectional study, so we cannot give causality in the similar way as prior interventional literatures or longitudinal follow-up cohort studies. Therefore, our results cannot be concluded as complete information about adiponectin genetic polymorisms in all Egyptin population due to the small sample size. Finally, our study didn’t include the effect of environmental influences, lifestyle, and gene–gene interactions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our results showed that the adiponectin + 45 T/G SNP could be a risk factor for developing peripheral neuropathy in our Egyptian diabetic patients, impacting the disease severity considering TCSS score. The adiponectin − 11,391 SNP could be associated with DPN but not the severity of the disease. Moreover, adiponectin + 276 G/T SNP could be a protective factor regarding DPN risk and the severity of the disease. Nonetheless, In future work, we recommended that these SNPs should be recognized by structured prospective studies to analyze how these genetic mutations cause or accelerate DPN and their possible interaction with other risk factors. Thus, a definite assessment of the possible relationship probably needs the addition of more studies and larger sample sizes applied on DPN patients in different population and ethinities. Moreover, it is important to apply this genetic information to diabetic cases to determine the individuals at high risk for developing DPN to make precautionary strategies and modify the treatment protocol by selecting medication, dosage, and route of administration. Finally, future studies should be applied updated molecular technology techiques rather than PCR-RFLP to analyze the aformetioned SNPs.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study data are provided within supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DF:

-

Diabetic nephropathy

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- DPN:

-

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy

- DR:

-

Diabetic retinopathy

- DWPN:

-

Diabetic patients without peripheral neuropathy

- HBA1C:

-

Hemoglobin A1C

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NDPN:

-

Non-diabetic peripheral neuropathy

- PCR-RFLP:

-

Polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- T1DM:

-

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 Diabetes mellitus

- TCSS:

-

The Toronto Clinical Scoring System

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

References

Zheng, Y., Ley, S. H. & Hu, F. B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14 (2), 88–98 (2018).

Yang, Y. & Wang, P. Association of CYP19A1 and CYP1A2 genetic polymorphisms with type 2 diabetes mellitus risk in the Chinese Han population. Lipids Health Dis. 19 (1), 187 (2020).

International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas [EB/OL]. IDF diabetes atlas 9th edition (2019). http://www.diabetesatlas.org/. Accessed 3 Oct 2021.

Saeedi, P. et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 157, 107843 (2019).

Hegazi, R. et al. Epidemiology of and risk factors for type 2 diabetes in Egypt. Ann. Glob Health. 81 (6), 814–820 (2015).

Faselis, C. et al. Complications of type 2 diabetes Mellitus. Curr. Vasc Pharmacol. 18 (2), 117–124 (2020).

Zhao, Y. et al. Genetics of diabetic neuropathy: systematic review, meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. 6, 1996–1913 (2019).

Ma, O. K. et al. Identification of a novel adiponectin receptor and opioid receptor dual acting agonist as a potential treatment for diabetic neuropathy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 158, 114141 (2023).

Carmichael, J. et al. Advances in screening, early diagnosis and accurate staging of diabetic neuropathy. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 671257 (2021).

Kallinikou, D. et al. Diabetic neuropathy in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and associated genetic markers. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 35, e3178 (2019).

Alkanlı, N., Ay, A. & Alkanlı, S. S. Investigation of the relationship between microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus and proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-18 gene variations. Gevher Nesibe J. Med. Health Sci. 5 (7), 67–66 (2020).

Jialal, I. et al. Neutrophil and monocyte ratios to high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and adiponectin as biomarkers of nascent metabolic syndrome. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig ; 41 (2). (2020).

D’Marco, L. et al. Epicardial adipose tissue, adiponectin and leptin: a potential source of cardiovascular risk in chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (3), 978 (2020).

Palit, S. P. et al. A genetic analysis identifies a haplotype at adiponectin locus: Association with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 2904 (2020).

Alimi, M., Goodarzi, M. T. & Nekoei, M. Association of ADIPOQ rs266729 and rs1501299 gene polymorphisms and circulating adiponectin level with the risk of type 2 diabetes in a population of Iran: a case–control study. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 20, 87–83 (2021).

Howlader, M. et al. Adiponectin gene polymorphisms associated with diabetes mellitus: a descriptive review. Heliyon 7 (8), e07851 (2021).

Li, F. Y. L. et al. Cross-talk between adipose tissue and vasculature: role of Adiponectin. Acta Physiol. (Oxford, England). 203 (1), 167–180 (2011).

Ohashi, K. et al. Adiponectin promotes macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 285(9), 6153–60 (2010).

Ghantous, C. M. et al. Differential role of leptin and adiponectin in cardiovascular system. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 534320 (2015).

Esmaili, S., Hemmati, M. & Karamian, M. Physiological role of adiponectin in different tissues: a review. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 126 (1), 67–63 (2020).

Bushra, S. et al. Adiponectin ameliorates hyperglycemia-induced retinal endothelial dysfunction, highlighting pathways, regulators, and networks. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 3135–3166 (2022).

Askwith, T. et al. Oxidative stress and dysregulation of the taurine transporter in high-glucose-exposed human Schwann cells: Implications for pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297(3), E620-8 (2009).

Chen, T. et al. Association of serum adiponectin with intima media thickness of dorsalis pedis artery and macroangiopathy in type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 4739271 (2020).

Sun, Q. et al. Serum aadiponectin levels are positively associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 11, 567959 (2020).

Isakova, J. et al. ADIPOQ, KCNJ11 and TCF7L2 polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes in Kyrgyz population: a case control study. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 23 (2), 1628–1631 (2019).

Hossain, M. M. & Howlader, M. The Rs2241766, Rs266729 and Rs1501299 polymorphisms in ADIPOQ gene play substantial role in predisposition to diabetes. Der Pharmacia Lettre. 14 (1), 06–11 (2022).

Takahashi, M. et al. Genomic structure and mutations in adipose-specific gene, adiponectin. Int. J. Obes. 7, 861 (2000).

Menzaghi, C., Trischitta, V. & Doria, A. Genetic influences of adiponectin on insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 56, 1198–1209 (2007).

Hasani-Ranjbar, S. et al. Genetic association analysis of the adiponectin polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes with and without complications. Iran. J. Diabetes Lipid Disorders. 10, 1–4 (2011).

Choe, E. Y. et al. Variants of the adiponectin gene and diabetic microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism 62 (5), 677–685 (2013).

Ji, Z. Y. et al. Association of adiponectin gene polymorphisms with an elevated risk of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes patients. J. Diabetes Complicat. 29, 887–892 (2015).

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 31, 55–60 (2008).

Dyck, P. J., Carter, R. E. & Litchy, W. J. Modeling nerve conduction criteria for diagnosis of diabetic polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 44 (3), 340–345 (2011).

Bril, V. & Perkins, B. A. Validation of the Toronto Clinical Scoring System for diabetic polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care. 25 (11), 2048–2052 (2002).

Yang, Z. et al. Scoring systems to screen for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018 (7), CD010974 (2018).

Szopa, M. et al. Variants of the adiponectin gene and type 2 diabetes in a Polish population. Acta Diabetol. 46 (4), 317–322 (2009).

Han, L. Y. et al. Associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms (+ 45T > G, + 276G > T, – 11377C > G, – 11391G > A) of adiponectin gene and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 54 (9), 2303–2314 (2011).

El-Shal, A. S., Zidan, H. E. & Rashad, N. M. Adiponectin gene polymorphisms in Egyptian type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with and without diabetic nephropathy. Mol. Biol. Rep. 41 (4), 2287–2298 (2014).

Stephens, M., Smith, N. J. & Donnelly, P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 978–989 (2001).

Pop-Busui, R. et al. Inflammation as a therapeutic target for diabetic neuropathies. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 16, 29 (2016).

Cole, J. B. & Florez, J. C. Genetics of diabetes mellitus and diabetes complications. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 16 (7), 377–390 (2020).

Mohammadzadeh, G. & Zarghami, N. Associations between single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the adiponectin gene, serum adiponectin levels and increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Iranian obese individuals. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 69 (7), 764–771 (2009).

Motawi, T., Salman, T., Shaker, O. & Abdelhamid, A. Association of polymorphism in adiponectin (+ 45 T/G) and leptin (–2548 G/A) genes with type 2 diabetes mellitus in male egyptians. Arch. Med. Sci. 11 (5), 937–944 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Yao YAssociation of adiponectin SNP + 45 and SNP + 276 with type 2 diabetes in Han Chinese populations: a meta-analysis of 26 case-control studies. PLoS One. 6 (5), e19686 (2011).

Rudofsky, G. Jr. et al. No association of the 94T/G polymorphism in the adiponectin gene with diabetic complications. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 7(4), 455–459 (2005).

Al-Daghri, N. et al. Adiponectin gene variants and the risk of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38 (6), 3703–3708 (2011).

Flyvbjerg, A. Pathogenesis of microvascular complications. Chapter 37. Textbook of Diabetes Microvascular Complications in Diabetes, Fifth Edition. 1104 Page 2016. (2017). Published 2017 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Xia, H., Mo, Y. Z., Bian, R. W., Shen, J. & Ma, L. J. Correlation between single nucleotide polymorphism of adiponectin gene and type 2 diabetes in Chinese. Chin. J. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 20, 236–237 (2004).

Wang, S. F., Zhao, J. J., Jiang, Q., Gao, L. & Ma, H. The correlation betwween adiponectin gene polymorphism and type 2 diabetes. Chin. J. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 23, 51–52 (2007).

Hao, J. M., Dian, Z. H. & Liu, J. X. Correlation between single nucleotide polymorphism of adiponectin gene and type 2 diabete in Han population of Hainan. Hainan Med. J. 20, 1–3 (2009).

Mackawy, A. M. H., Alzohairy, M. A. A., Ahmed, E. A. A. & Badawy, M. E. H. Adiponectin gene polymorphism and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in obese patients in Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia. J. Am. Sci. 7 (12), 432–443 (2011).

Siitonen, N. et al. Association of ADIPOQ gene variants with body weight, type 2 diabetes and serum adiponectin concentrations: the Finnish diabetes Prevention Study. BMC Med. Genet. 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-12-5 (2011). PMID: PMCID:.

Thirunavukkarasu, A., Nithya, R., Muthukumaran, K. & Sivasankari, C. Association of the 45 T/G and 276 G/T Polymorphisms in the adiponectin gene with type 2 diabetes in South Indian population. J. Environ. Res. Develop. 8 (3A), 563–567 (2014).

Yu, T. K., Maung, K. K., Thida, A. & Myint, T. Single nucleotide polymorphism at + 276 G > T of the adiponectin gene and plasma adiponectin level in Myanmar type 2 diabetic patients. J. ASEAN Fed. Endocr. Soc. 33 (2), 160–164 (2018).

Demir, S. et al. Emerging targets in type 2 diabetes and diabetic ccomplications. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 8 (18), e2100275 (2021).

Cecilia, O.-M. et al. Oxidative Stress as the Main Target in Diabetic Retinopathy Pathophysiology. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 8562408 (2019).

Zhang, H., Wang, L. & Chu, Y. Reactive oxygen species: the signal regulator of B cell. Free Radic Biol. Med. 142, 16–22 (2019).

Irazabal, M. V. & Torres, V. E. Reactive oxygen species and redox signaling in chronic kidney disease. Cells 9, 1342 (2020).

Kang, Q. & Yang, C. Oxidative stress and diabetic retinopathy: molecular mechanisms, pathogenetic role and therapeutic implications. Redox Biol. 37, 101799 (2020).

Menzaghi, C. et al. A haplotype at the adiponectin locus is associated with obesity and other features of the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes 51 (7), 2306–23s12 (2002).

de Luis, D. A. et al. Role of rs1501299 variant in the adiponectin gene on total adiponectin levels, insulin resistance and weight loss after a Mediterranean Hypocaloric diet. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 148, 262–267 (2019).

Kacso, I. M. et al. 276G > T polymorphism of the ADIPOQ gene influences plasma adiponectin in type 2 diabetes patients but is not predictive for presence of type 2 diabetes in a caucasian cohort from Romania. Maedica (Bucur). 7 (4), 271–276 (2012).

Hamza, A. A., Albadiri, M. Q., Ali, A. & Ahmed, A. A. Impact of the rs17300539 SNP in ADIPOQ gene on the development of diabetic nephropathy in T2DM in Iraqi population from middle Euphrates region. Lat Am. J. Pharm. 43(special issue, Part 5), 1812–1819 (2024).

Nomani, H. et al. Association between the – 11377 C/G and – 11391 G/A polymorphisms of adiponectin gene and adiponectin levels with susceptibility to type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in population from the west of Iran, correlation with lipid profile. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 (3), 3574–3582 (2019). Discu.

Vasseur, F. et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphism haplotypes in the both proximal promoter and exon 3 of the APM1 gene modulate adipocyte-secreted adiponectin hormone levels and contribute to the genetic risk for type 2 diabetes in French caucasians. Hum. Mol. Gen. 11, 2607–2614 (2002).

Olckers, A. et al. Protective effect against type 2 diabetes mellitus identified within the ACDC gene in a black South African diabetic cohort. Metabolism 56, 587–592 (2007).

Liu, Y., Li, H., Tanaka, K., Tsumaki, N. & Yamada, Y. Identification of an enhancer sequence within the first intron required for cartilage-specific transcription of the α2 (XI) collagen gene. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 12712–12718 (2000).

Wang, D. & Sadée, W. Searching for polymorphisms that affect gene expression and mRNA processing: Example ABCB1 (MDR1). AAPS J. 8, E515–E520 (2006).

Momin, A. A., Bankar, M. P. & Bhoite, G. M. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms of adiponectin gene with type 2 diabetes mellitus, and their influence on cardiovascular risk markers. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 32 (1), 53–60 (2017).

Hussain, M. K. et al. Adiponectin gene polymorphisms as a predictor for development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Iraqi population. Gene 662, 118–122 (2018).

Joshaghani, H. R. et al. Association of adiponectin gene polymorphisms and their haplotypes with type 2 diabetes and related metabolic traits in an Iranian population. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 40 (2), 216–222 (2020).

Shramko, I. et al. Polymorphism in adiponectin and adiponectin receptor genes in diabetes mellitus pathogenesis. Pathophysiology 29 (1), 81–91 (2022).

Al-Nbaheen, M. S. Effect of genetic variations in the ADIPOQ gene on susceptibility to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 15, 2753–2761 (2022).

Tabatabaei-Malazy, O. et al. Gender-specific differences in the association of adiponectin gene polymorphisms with body mass index. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 7 (3), 241–246 (2010).

Mackevics, V. et al. The adiponectin gene is associated with adiponectin levels but not with characteristics of the insulin resistance syndrome in healthy caucasians. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 14 (3), 349–356 (2006).

Dedoussis, G. V., Kaliora, A. C. & Panagiotakos, D. B. Genes, diet and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Rev. Diabet. Stud. 4 (1), 13–24 (2007).

Esteghamati, A. et al. Association of + 45(T/G) and + 276(G/T) polymorphisms in the adiponectin gene with coronary artery disease in a population of Iranian patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39 (4), 3791–3797 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged all subjects included in our study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NMB and SFS prepared the idea and designed the study. NMB and SFS did the data statistical analysis. NMB and SFS performed all the laboratory investigations and interpreted the patients’ data regarding each studied group. NAH and NFI selected the patients and the control group. All authors wrote, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Committee of Zagazig University and the International Review Board (IRB), Faculty of Medicine approved this study (reference number is IRB#:9623-5-1-2022).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakr, N.M., Hashim, N.A., Ibrahim, N.F. et al. Association between adiponectin single nucleotide polymorphisms and the risk of diabetic polyneuropathy. Sci Rep 15, 3872 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86143-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86143-3