Abstract

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a lipoprotein with potent atherogenic and thrombogenic potential. Its role in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) combined with three-vessel disease (TVD) remains unclear. This study aimed to investigate the correlation between Lp(a) levels and the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with ACS combined with TVD. Patients who underwent coronary angiography and were diagnosed with ACS combined with TVD were selected for the study. Patients were divided into three groups based on their Lp(a) levels. The correlation between Lp(a) and MACE was evaluated using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis, subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curve, receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC), and restricted cubic spline plot (RCS). A total of 1504 patients were included, with a median follow-up time of 38 months. Univariate Cox regression analysis showed that patients with higher Lp(a) levels had a significantly increased incidence of MACE (P < 0.001). After adjusting for confounding factors, multivariate Cox regression analysis indicated that high Lp(a) levels remained an independent predictor of MACE (P < 0.05). Subgroup analysis revealed that higher Lp(a) levels were significantly associated with a higher risk of MACE in subgroups including patients aged ≥ 60 years, males, those with hypertension, CKD, without diabetes, without hyperlipidemia, and without stroke (P < 0.05). Sensitivity analysis further confirmed the close correlation between Lp(a) and MACE (P < 0.05). Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that the cumulative incidence of MACE in the high Lp(a) group was significantly higher than in the low-level group (P < 0.001). The ROC curve analysis indicated that Lp(a) had some predictive value for the occurrence of MACE (AUC: 0.623, 95% CI: 0.593–0.653, P < 0.001). The RCS plot demonstrated that after transforming Lp(a) to a normal distribution as Log10Lp(a), there was an approximately U-shaped nonlinear association between Log10Lp(a) and the risk of MACE (P nonlinear < 0.001). Lp(a) levels were significantly associated with the risk of MACE in patients with ACS combined with TVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), encompassing conditions such as unstable angina and myocardial infarction that arise from acute myocardial ischemia, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), a composite of multiple adverse cardiovascular outcomes such as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke, being major contributors to this burden1,2,3. Among patients with ACS, those with three-vessel disease (TVD), defined as significant stenosis (≥ 50% narrowing) in all three major coronary arteries (left anterior descending, left circumflex, and right coronary arteries), are particularly vulnerable due to the extensive and severe nature of their coronary artery disease (CAD)4. Despite advances in treatment, the prognosis for these high-risk patients remains poor, emphasizing the need for improved risk stratification tools. Identifying reliable biomarkers that can predict the risk of MACE in this high-risk population is crucial for improving clinical outcomes. Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is an emerging biomarker of interest5.

Lp(a) is a lipoprotein particle structurally similar to low-density lipoprotein (LDL), but it includes an additional protein called apolipoprotein(a)5. Genetic variations in the LPA gene, which encodes apolipoprotein(a), contribute to the wide variability of Lp(a) levels in the population, making it a stable and inheritable risk factor6. Elevated levels of Lp(a) are recognized as a genetic risk factor for atherosclerosis and thrombosis, contributing to the development and progression of CVD7,8. Compared to other well-known biomarkers predictive of MACE, such as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), Lp(a) possesses unique biological characteristics and predictive advantages. The literature indicates that Lp(a) levels are primarily determined by genetic factors and are minimally influenced by external conditions, making it a stable and reproducible risk factor9. Additionally, Lp(a) plays a significant role in promoting the formation and instability of atherosclerotic plaques10. Its ability to inhibit the fibrinolytic system and induce inflammatory responses further contributes to its dual role in increasing the risk of thrombosis and cardiovascular events11. While traditional biomarkers like LDL-C, triglycerides, and HbA1c are critical for assessing cardiovascular metabolic risk, they primarily reflect lipid metabolism disorders or glycemic abnormalities, which are distinct from the genetic cardiovascular risk represented by Lp(a). Studies have demonstrated that Lp(a) has unique clinical value in evaluating residual cardiovascular risk, particularly in patients who experience cardiovascular events despite normal levels of traditional risk factors12,13. Therefore, investigating the predictive value of Lp(a) for MACE risk in ACS patients with TVD not only addresses gaps in existing research but also provides new insights and directions for personalized treatment strategies. Recent studies suggest that Lp(a) levels may serve as an independent predictor of cardiovascular outcomes, offering potential insights into residual cardiovascular risk, while the relationship between Lp(a) levels and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ACS and TVD remains complex and not fully understood14,15,16,17,18. The high complexity of their disease and elevated risk of adverse outcomes make this subgroup especially important for investigating the prognostic value of Lp(a). A better understanding of the role of Lp(a) in this specific population could help refine risk stratification models and guide personalized treatment strategies. Besides, variations in study designs, populations, and endpoints have also led to inconsistent findings, highlighting the need for more targeted research in this specific patient group.

Therefore, given the importance of Lp(a) in CVD and its potentially complex relationship with MACE, this study aimed to systematically investigate the association between Lp(a) levels and the risk of MACE in patients with ACS and TVD. By addressing the existing gaps in the literature and focusing specifically on the high-risk TVD population, this research seeks to provide clearer insights into the prognostic value of Lp(a). By conducting a retrospective analysis of a large patient cohort, we aimed to evaluate the impact of Lp(a) levels on the risk of MACE at different levels, thereby elucidating its potential value in clinical risk assessment and personalized treatment.

Methods

Study subjects

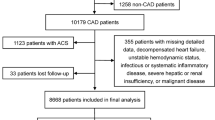

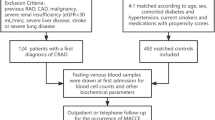

In this retrospective cohort-based observational study, we included the study population from patients with ACS combined with TVD who were treated at Zhongda Hospital affiliated to Southeast University, from July 1, 2013, to December 31, 2021. All patient records were reviewed retrospectively, and data collection was conducted through the hospital’s electronic medical record system.

Inclusion criteria for study participants: (1) Age ≥ 18 years; (2) Diagnosed with ACS, including acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction) and unstable angina; (3) Diagnosed with TVD via coronary angiography, indicating significant stenosis (≥ 50%) in the left anterior descending artery, left circumflex artery, and right coronary artery.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Presence of other severe diseases, such as advanced malignancies, severe hepatic or renal insufficiency; (2) History of heart transplantation or other major cardiac surgeries; (3) Incomplete data, significantly abnormal data, or loss to follow-up, making it impossible to perform subsequent follow-up and data analysis.

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 1504 patients with ACS combined with TVD were included in this study (Figure S1). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital affiliated to Southeast University (Approval number: 2023ZDSYLL141-P01). This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Since this was a retrospective study involving existing medical records, direct patient contact was not required, and informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital affiliated to Southeast University.

Data collection

The data for this study were primarily collected through the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) system as part of a retrospective analysis. The data collection process adhered strictly to ethical guidelines, and all patient information was anonymized during analysis to ensure privacy and confidentiality. Data collection was standardized, with all extracted variables independently checked by two trained researchers to ensure accuracy. (1) Basic information and clinical parameters: Basic patient information, including age, gender, and smoking status, was collected through the EHR system. Medical history information, such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stroke, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the use of antihypertensive and antidiabetic medications, was obtained by reviewing medical records. Data collection was standardized, with all extracted variables checked independently by two trained researchers to ensure accuracy. (2) Anthropometric measurements: Trained nurses measured the patients’ height and weight under standardized conditions to calculate the body mass index (BMI). Blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) and heart rate were measured by experienced medical personnel using a calibrated sphygmomanometer after the patient had rested in a static environment for at least five minutes. (3) Laboratory tests: Blood samples were collected from all participants at the initial diagnosis upon enrollment to measure biochemical markers, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG), HbA1c, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), LDL-C, apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), Lp(a), albumin, uric acid (UA), and fibrinogen. Samples were processed within 2 h of collection and analyzed in the hospital’s central laboratory using standardized protocols to ensure consistent quality control. (4) Clinical assessments: The GRACE score and Gensini score systems were used to evaluate the risk and severity of CVD. Additionally, echocardiography was performed to assess left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). All echocardiographic assessments followed American Society of Echocardiography guidelines, and the inter-observer variability was minimized through double reading by two independent cardiologists.

Data definition

In this study, smoking refers to a history of smoking, including current smokers and those who have quit smoking in the past. Hypertension is defined as persistently elevated blood pressure, typically defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg, or the use of antihypertensive medications19. Diabetes is defined as FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L, or the use of antidiabetic medications20. For patients on glucose-lowering medications, medical records were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis. Hyperlipidemia refers to abnormal lipid levels, including TC ≥ 5.2 mmol/L, LDL-C ≥ 3.4 mmol/L, triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L, or the use of lipid-lowering medications21. All lipid measurements were conducted in the fasting state, and values were verified using the hospital’s central laboratory records. Stroke is defined as brain function impairment caused by vascular occlusion (ischemic stroke) or rupture (hemorrhagic stroke), diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and imaging studies22. The CKD refers to persistent kidney function impairment, characterized by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min/1.73 m², elevated urinary protein levels for more than 3 months, or evidence of structural kidney damage23. The GRACE score is a system used to assess short-term and long-term mortality risk in patients with ACS, calculated based on factors such as age, heart rate, blood pressure, creatinine levels, heart function class, and cardiac enzyme levels24. Score calculation was performed using an online GRACE calculator tool, ensuring standardization. The Gensini score is used to assess the severity of coronary artery disease, based on the degree and extent of coronary artery stenosis, reflecting the overall burden of coronary artery disease25. Coronary angiographic data were reviewed by two independent interventional cardiologists to calculate the score, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. The eGFR is a method to estimate kidney function, calculated based on serum creatinine levels, age, and gender, expressed in mL/min/1.73 m226. The CKD-EPI equation was used, as it provides better accuracy for a wide range of populations compared to older formulas.

Follow-up outcomes

Patients were regularly followed up from the time of discharge until December 31, 2022. Follow-up was conducted through outpatient visits and telephone interviews every six months. All follow-up data were verified against hospital records to ensure completeness. The main focus was on the occurrence of MACE, including cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, and unplanned revascularization due to cardiovascular causes. Cardiovascular death was defined as death directly attributed to myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, arrhythmia, sudden cardiac arrest, or other cardiovascular-related complications. Non-fatal myocardial infarction was defined as evidence of myocardial injury (cardiac biomarkers such as troponin levels exceeding the 99th percentile upper reference limit) and meeting at least one of the following criteria: symptoms of ischemia, new or presumed new significant ST-segment-T wave changes, new left bundle branch block, pathological Q waves on the electrocardiogram, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality27. Non-fatal stroke was defined as a sudden onset of focal or global neurological symptoms lasting ≥ 24 h or requiring hospitalization, confirmed by imaging evidence of cerebral infarction (ischemic stroke) or intracranial hemorrhage (hemorrhagic stroke), excluding transient ischemic attacks28. Unplanned revascularization was defined as any unplanned percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery performed due to symptoms of myocardial ischemia, objective evidence of ischemia, or progression of CAD, excluding procedures performed during the initial hospitalization unless indicated by a new ischemic event29.

Measurement of lipoprotein(a)

In this study, the measurement of Lp(a) was performed using an immunoturbidimetric method (LASAY Lipoprotein(a) auto; SHIMA laboratories Co., Ltd). This technique is based on the principle that the formation of antigen-antibody complexes increases the turbidity of the solution, and the concentration of Lp(a) in the blood is quantitatively analyzed by measuring the increase in light scattering30. The method utilizes highly specific antibodies that bind to the apolipoprotein(a) component of Lp(a), forming large molecular complexes that lead to increased light scattering. By comparing the changes in light scattering to a standard curve with known concentrations, the Lp(a) concentration in the sample can be accurately determined. The reference range for Lp(a) in this study was set between 100 and 300 mg/L, with a detection limit of 2 mg/L. The method exhibits high specificity, enabling the accurate quantification of very low levels of Lp(a). All patients were divided into three groups based on the tertiles of Lp(a): T1: ≤ 184 mg/L, T2: 184–375 mg/L, T3: > 375 mg/L. The tertile cutoff points were determined based on the actual distribution of Lp(a) levels in the study population to ensure an even distribution of patients across the groups. This approach facilitates meaningful comparisons and allows for a clear assessment of the impact of different Lp(a) levels on the risk of MACE.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we utilized various statistical methods to analyze the data. Before conducting statistical analyses, all variables were checked for missing data and outliers. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation, and outliers were evaluated for their potential impact on the results. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the distribution differences of categorical variables, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the differences of continuous variables among the three groups. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Tukey’s test for ANOVA and Dunn’s test for the Kruskal-Wallis test to identify specific group differences.

Variables significantly associated with MACE were identified through univariate Cox regression analysis. These variables were then included in a multivariate Cox regression model to adjust for potential confounding factors. Confounders were selected based on clinical relevance and statistical significance (P < 0.05 in univariate analysis), and collinearity was checked using variance inflation factors. The results were expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). To further investigate differences among subgroups, we performed stratified analyses based on age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, stroke, and CKD. Multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted within each subgroup to evaluate the impact of various variables in different subgroups. Furthermore, to ensure the robustness of the results, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by excluding patients with eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 to validate the robustness of the model and the reliability of the association between Lp(a) and MACE. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to plot survival curves, and the Log-rank test was employed to compare event-free survival rates between different groups. Time points for survival analysis were set based on clinically meaningful intervals, and survival probabilities were calculated with 95% CIs. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to analyze the predictive ability of Lp(a) for MACE, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the discriminative power of the model. Finally, restricted cubic spline (RCS) plot was used to illustrate the nonlinear relationship between Lp(a) and MACE. The RCS plot provided a clearer visualization of the trend in the effect of Lp(a) on MACE. Data analysis was primarily conducted using R language (version 4.1.3) and SPSS software (version 26.0). R was used for plotting survival curve and RCS plot, while SPSS was employed for basic statistical descriptions and regression analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided, with a significance level set at P < 0.05.

Results

Clinical characteristics based on lp(a) grouping

Table 1 summarized the clinical characteristics of patients stratified into three groups based on Lp(a) tertiles. Significant differences were observed across the groups for variables including age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CKD, antidiabetic drugs, GRACE score, Gensini score, BMI, LVEF, TC, triglycerides, LDL-C, ApoA1, ApoB, albumin, eGFR, and fibrinogen (P < 0.05). Notably, the incidence of MACE increased progressively with higher Lp(a) levels (P < 0.001).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of the association between Lp(a) and MACE

Univariate Cox regression analysis (Table 2) identified several factors significantly associated with MACE, including age, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, CKD, antihypertensive drugs, antidiabetic drugs, GRACE score, Gensini score, LVEF, FPG, HbA1c, albumin, uric acid, eGFR, and fibrinogen (P < 0.05).

Multivariate Cox regression models were constructed using variables with P < 0.05 from the univariate analysis. In the fully adjusted model (Model 4), Lp(a) was independently associated with MACE, both as a categorical and continuous variable. Patients in the T3 group of Lp(a) had a 1.363-fold higher risk of MACE compared to the T1 group (HR: 1.363, 95% CI: 1.088–1.709, P = 0.007). Similarly, each unit increase in Log10Lp(a) corresponded to a 43.7% higher risk of MACE (HR: 1.437, 95% CI: 1.122–1.841, P = 0.004) (Table 3). Furthermore, based on the fully adjusted Model 4, we additionally adjusted for several lipid parameters (such as triglycerides, HDL-C, LDL-C, ApoA1, and ApoB) to construct a new model, and the results still confirmed the independent association between Lp(a) and the risk of MACE (P < 0.05) (Table S1).

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

Subgroup analysis (Table 4) revealed a stronger association between elevated Lp(a) levels and MACE risk in specific subgroups, including patients aged ≥ 60 years, males, and those with hypertension or CKD, and those without diabetes, hyperlipidemia or stroke. In these subgroups, patients in the T3 group of Lp(a) had a 1.366–1.567 times higher risk of MACE compared to the T1 group (P < 0.05).

Sensitivity analysis (Table 5) showed that even after excluding patients with eGFR < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, higher Lp(a) levels remained significantly associated with increased MACE risk (P < 0.05).

Visualization of the correlation between Lp(a) and MACE

The Kaplan-Meier curve (Fig. 1A) showed that patients in the T3 group had significantly lower MACE-free survival compared to the T1 group (P < 0.001). The ROC curve (Fig. 1B) indicated that Lp(a) had moderate predictive value for MACE (AUC: 0.623, 95% CI: 0.593–0.653, P < 0.001). Furthermore, the RCS plot (Fig. 1C) revealed a U-shaped nonlinear association between Log10Lp(a) and MACE risk (P nonlinear < 0.001).

Discussion

This study found that Lp(a) levels were significantly associated with the risk of MACE in patients with ACS combined with TVD. Patients with higher Lp(a) levels had a significantly increased incidence of MACE, and after adjusting for confounding factors, Lp(a) remained an independent predictor of MACE. Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis further validated this association. Additionally, the study demonstrated an approximately U-shaped nonlinear relationship between Log10Lp(a) and the risk of MACE. These findings suggest that monitoring and controlling Lp(a) levels may help reduce the risk of MACE in patients with ACS combined with TVD, providing important implications for clinical management.

Despite current evidence suggesting a close association between Lp(a) with CVD and mortality31,32,33, the association between Lp(a) and adverse prognosis in CVD patients still requires further discussion. For example, a retrospective cohort analysis by Berman et al. involving 16,419 patients indicated that elevated Lp(a) levels were significantly associated with long-term MACE, regardless of the presence of baseline CVD34. Additionally, in another retrospective study involving 262 patients with AMI, high Lp(a) levels (≥ 32 mg/dL) were associated with a significantly increased risk of MACE35. In addition, in a study involving 2,086 patients who underwent PCI for in-stent restenosis, those with elevated baseline Lp(a) levels had a significantly increased risk of MACE during a median follow-up period of 36 months36. Additionally, Zhang et al., in a single-center retrospective cohort study involving 1,168 ischemic heart failure patients undergoing elective PCI, found that elevated serum Lp(a) levels were independently associated with an increased risk of MACE, all-cause mortality, and revascularization, with a more pronounced effect observed in obese patients37. And in a study involving 300 AMI patients, Wang et al. established a myocardial ischemia‒reperfusion injury (MIRI) grading system based on clinical manifestations and coronary angiography and found that as the MIRI grade increased, Lp(a) levels significantly rose, cardiac function deteriorated, and the one-year incidence of MACEs significantly increased, particularly in patients with three-vessel disease and high Lp(a) levels, suggesting that elevated Lp(a) levels may exacerbate myocardial injury and substantially increase the risk of poor prognosis, providing important insights for risk assessment and intervention strategies38. And Li et al. in a prospective cohort study involving 1,543 STEMI patients who underwent emergency PCI, demonstrated that elevated Lp(a) levels (≥ 50 mg/dL) significantly increased the risk of MACE in patients with diabetes, while no similar association was observed in non-diabetic patients39. This finding indicates that high Lp(a) levels have a markedly adverse impact on the prognosis of such patients, with the risk being particularly pronounced in those with diabetes. Moreover, in patients with AMI, a study indicated that higher Lp(a) levels were positively associated with the risk of long-term recurrent myocardial infarction, exhibiting a nonlinear relationship, but are not significantly associated with all-cause mortality, and subgroup analysis revealed no significant differences in the impact of Lp(a) on recurrent myocardial infarction among different populations, which highlights the potential impact of elevated Lp(a) levels on recurrent myocardial infarction, though its clinical significance requires further prospective investigation40. However, in a single-center retrospective study, Park et al. analyzed the impact of baseline Lp(a) levels on long-term clinical outcomes in 1,908 Korean AMI patients, the results showed that baseline Lp(a) levels were not independently associated with the occurrence of MACE within three years41. And another retrospective cohort study that included 295 patients with coronary artery disease and psoriasis found that high Lp(a) levels were not significantly associated with adverse outcomes over a 3-year period in the overall population42. The above studies indicate that there is no consensus on the correlation between Lp(a) and MACE. Our study, while verifying the correlation between Lp(a) and the risk of MACE in patients with ACS combined with TVD, further revealed a nonlinear relationship between Lp(a) and MACE. This suggests that the correlation between Lp(a) and MACE may be complex and could vary depending on the study population. Therefore, more research is needed in the future to further explore their association.

Furthermore, the potential mechanisms by which Lp(a) promotes the occurrence of MACE also need further discussion. First, Lp(a) carries a large amount of oxidized phospholipids, which can promote the formation of foam cells within the arterial wall, accelerating the formation and progression of atherosclerotic plaques43. Second, the apolipoprotein(a) component in Lp(a) is similar to plasminogen and can competitively inhibit the activation of plasminogen, leading to impaired fibrinolytic system function and an increased risk of thrombosis44. Third, Lp(a) can induce vascular endothelial cells and monocytes to release various pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, exacerbating the inflammatory response45. Fourth, Lp(a) increases the oxidation tendency of LDL, promoting the development of atherosclerosis and potentially leading to plaque instability46. Fifth, Lp(a) can also promote the proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells, further exacerbating atherosclerotic lesions47. Sixth, Lp(a) may promote the occurrence and development of coronary lesions, thereby contributing to the adverse prognosis of CVD48. Additionally, we observed an approximately U-shaped nonlinear relationship between Log10Lp(a) levels and the risk of MACE. This finding suggests that Lp(a) levels may not simply follow the principle of “the lower, the better”. Extremely low Lp(a) levels could potentially impair physiological repair functions, such as tissue repair and anti-inflammatory effects, thus increasing the risk of MACE. Conversely, high Lp(a) levels exacerbate atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and inflammation, leading to a significantly increased MACE risk. However, the exact biological basis for this U-shaped relationship remains unclear and warrants further investigation. Future studies should aim to validate this observation and explore the mechanistic pathways underlying both low and high Lp(a) levels and their impact on cardiovascular outcomes.

Since Lp(a) levels are primarily determined by genetics, conventional lifestyle modifications and lipid-lowering therapies have limited effects on them. Therefore, optimized management of patients with elevated Lp(a) levels is particularly important. Currently, targeted therapies for Lp(a), such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), are emerging as research hotspots, offering new strategies for reducing cardiovascular risk49. Notably, a clinical trial found that Lp(a) levels significantly increased during the peri-infarction and early postinfarction period in patients with AMI, especially in those with higher Lp(a) levels at admission50. However, a single subcutaneous dose of evolocumab administered within 24 h of admission effectively prevented the increase in Lp(a) levels, suggesting that PCSK9 inhibitors may have potential clinical value in managing Lp(a) during the peri-infarction period. This indicates that, in addition to controlling traditional cardiovascular risk factors, interventions targeting Lp(a) levels may offer new strategies for reducing the risk of MACE. Interestingly, another study found that Lp(a) levels in STEMI patients were lowest during the acute phase, gradually increased thereafter, and peaked at follow-up 3 to 6 months post-discharge51. This dynamic change suggests that repeated measurements of Lp(a) levels after myocardial infarction may be crucial for guiding future treatments, particularly in identifying high-risk patients and optimizing interventions.

This study provided strong evidence for the association between Lp(a) levels and MACE risk in patients with ACS combined with TVD, with several notable strengths. First, it leveraged a large, well-defined cohort with detailed clinical data, which enhances the reliability and statistical power of the findings. Second, the use of subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis strengthened the validity of the results by addressing the potential variability and robustness of the association. Third, the discovery of a U-shaped nonlinear relationship between Log10Lp(a) and MACE risk provides a new perspective for the existing literature and highlights the complex role of Lp(a) in cardiovascular risk. This finding is particularly significant as it contrasts sharply with previous studies that primarily focused on linear relationships between Lp(a) levels and cardiovascular risk. The observation of a U-shaped curve indicates that both extremely high and low levels of Lp(a) may increase the risk of MACE. Although this U-shaped relationship was not entirely anticipated, it reveals the bidirectional complexity of Lp(a)’s role in CVD. Moreover, this finding is novel within the specific high-risk population of ACS combined with TVD, as previous studies have rarely explored such relationships in this subgroup. To translate this discovery into clinical practice, we recommend that future research focus on identifying an optimal range of Lp(a) levels that balances its beneficial and harmful effects. This could provide a basis for monitoring and controlling Lp(a) levels to reduce the risk of MACE in patients with ACS and TVD. At present, larger prospective studies are needed to validate this relationship and determine specific target ranges for intervention. However, several limitations must be acknowledged to provide a balanced interpretation of the findings. First, as an observational study, it cannot establish a causal relationship. While a significant association was found between elevated Lp(a) levels and increased MACE risk, residual confounding due to unmeasured factors, such as genetic predispositions, inflammatory markers, or environmental influences, cannot be ruled out. These factors might have biased the observed association, potentially overestimating or underestimating the true effect. Second, the sample in this study mainly consisted of an Asian population, which may limit the generalizability of the results to other ethnicities or regions. For instance, Lp(a) levels and their impact on cardiovascular risk are known to vary significantly across populations, with African ancestry populations typically having higher levels and potentially different risk profiles52. This ethnically homogeneous cohort may not fully represent the broader global population. Third, although various confounding factors were adjusted for, the possibility of residual confounding cannot be completely excluded. For example, socioeconomic status, dietary habits, or other behavioral factors that were not accounted for might have influenced the outcomes. These unmeasured confounders could have introduced bias, complicating the interpretation of the findings. Fourth, due to the relatively short study duration, the impact of changes in Lp(a) levels on long-term prognosis could not be assessed. Acute phase reactions, particularly during or after cardiovascular events, may cause transient elevations in Lp(a) levels. This raises the possibility of misclassification in baseline measurements, and longer follow-up periods are required to assess the stability and long-term implications of Lp(a) levels. Finally, there may be some measurement error in the assessment of Lp(a) levels. Although standardized assays were used, potential variability in pre-analytical handling, assay calibration, or unit reporting (e.g., mg/dL versus nmol/L) could have introduced imprecision. Such errors might have attenuated the observed associations, leading to an underestimation of the true impact. Furthermore, selection bias may also exist, as the study included only patients with ACS and TVD who survived the acute phase. This could potentially exclude patients with more severe conditions, thereby underestimating the true risk associated with elevated Lp(a) levels. In summary, while this study offers valuable insights into the relationship between Lp(a) and MACE risk, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Addressing these limitations in future studies with more diverse populations, robust study designs, and longer follow-up periods is essential to confirm and expand upon these results.

Conclusions

This large cohort study established a significant association between Lp(a) levels and the risk of MACE in patients with ACS combined with TVD, and revealed an approximately U-shaped nonlinear relationship between Log10Lp(a) and the risk of MACE. Even after adjusting for confounding factors, high Lp(a) levels remained an independent predictor of MACE. However, it is important to note that while the association is statistically significant, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to potential residual confounding and the observational nature of the study. The findings suggest that incorporating Lp(a) levels into routine monitoring and individualized treatment plans for patients with ACS combined with TVD may effectively improve long-term prognosis, reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events, and enhance patient quality of life. Nonetheless, further validation through prospective trials and randomized studies is needed before Lp(a) monitoring can be universally recommended. Future research should further explore the mechanisms of Lp(a) and evaluate the impact of Lp(a)-targeted interventions on patient outcomes.

Data availability

The data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Goldsborough, E. 3rd, Osuji, N. & Blaha, M. J. Assessment of Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A 2022 Update. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North. Am. 51(3), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2022.02.005 (2022).

Damluji, A. A. et al. Management of acute coronary syndrome in the older adult population: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 147(3), e32–e62. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001112 (2023).

Ma, Z. et al. Thrombospondin-1 plasma levels associated with in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. 375, 98–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.01.011 (2023).

SerruysPW et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):584]. N Engl. J. Med. 360(10), 961–972. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0804626 (2009). (published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2013 Feb 7;368(6):584).

Tsimikas, S. A test in context: Lipoprotein(a): Diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69(6), 692–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.042 (2017).

Kronenberg, F. & Utermann, G. Lipoprotein(a): Resurrected by genetics. J. Intern. Med. 273(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02592.x (2013).

Boffa, M. B. & Koschinsky, M. L. Lipoprotein (a): Truly a direct prothrombotic factor in cardiovascular disease? J. Lipid Res. 57(5), 745–757. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R060582 (2016).

Lampsas, S. et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic diseases: From pathophysiology to diagnosis and treatment. Molecules 28(3), 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28030969 (2023).

Marcovina, S. M. Lipoprotein(a): A genetically determined risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 60(8), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408363.2023.2229915 (2023).

Duan, Y. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is associated with the progression and vulnerability of new-onset carotid atherosclerotic plaque. Stroke 54(5), 1312–1319. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.042323 (2023).

Ugovšek, S. & Šebeštjen, M. Lipoprotein(a)-The crossroads of atherosclerosis, atherothrombosis and inflammation. Biomolecules 12(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12010026 (2021).

Hoogeveen, R. C. & Ballantyne, C. M. Residual Cardiovascular risk at low LDL: Remnants, Lipoprotein(a), and inflammation. Clin. Chem. 67(1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinchem/hvaa252 (2021).

Gomez-Delgado, F., Raya-Cruz, M., Katsiki, N., Delgado-Lista, J. & Perez-Martinez, P. Residual cardiovascular risk: When should we treat it? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 120, 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2023.10.013 (2024).

Ezhov, M. V., Tmoyan, N. A., Afanasieva, O. I., Afanasieva, M. I. & Pokrovsky, S. N. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular outcomes after revascularization of carotid and lower limbs arteries. Biomolecules 11(2), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom11020257 (2021).

Wang, Z. W., Li, M., Li, J. J. & Liu, N. F. Association of lipoprotein(a) with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 106, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2022.09.010 (2022).

Amiri, M. et al. Circulating lipoprotein (a) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 38(5), 485–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-022-00956-4 (2023).

Raitakari, O. et al. Lipoprotein(a) in youth and prediction of major cardiovascular outcomes in adulthood. Circulation 147(1), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060667 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Synergistic effect of lipoprotein(a) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein on the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A large prospective cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 15, 1392859. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2024.1392859 (2024).

Whelton, P. K. et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Executive summary—A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 71(6), 1269–1324. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066 (2018). [published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018 Jun;71(6):e136–e139. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000075] [published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018 Sep;72(3):e33. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYP.0000000000000080].

ElSayed, N. A. et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46(Suppl 1), S19–S40. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S00 (2023). [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2023 May 1;46(5):1106. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-er05] [published correction appears in Diabetes Care. 2023;46(9):1715. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-ad08.

Karantas, I. D., Okur, M. E., Okur, N. Ü. & Siafaka, P. I. Dyslipidemia management in 2020: An update on diagnosis and therapeutic perspectives. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord Drug Targets. 21(5), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871530320666200810144004 (2021).

Wu, S. et al. Stroke in China: Advances and challenges in epidemiology, prevention, and management. Lancet Neurol. 18(4), 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30500-3 (2019).

Levin, A. et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: Known knowns and known unknowns. Kidney Int. 105(4), 684–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.016 (2024).

Eagle, K. A. et al. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: Estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA 291(22), 2727–2733. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.291.22.2727 (2004).

Gensini, G. G. A more meaningful scoring system for determining the severity of coronary heart disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 51(3), 606. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80105-2 (1983).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150(9), 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009). (published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2011 Sep 20;155(6):408)

Thygesen, K. et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 138(20), e618-e651 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617 (published correction appears in Circulation. 2018 Nov 13;138(20):e652. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000632)

Sacco, R. L. et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 44(7), 2064–2089. https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0b013e318296aeca (2013). [published correction appears in Stroke. 2019 Aug;50(8):e239. doi: https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000205]

Neumann, F. J. et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur. Heart J. 40(2), 87–165. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394 (2019). ([published correction appears in Eur Heart J. 2019 Oct 1;40(37):3096. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz507)

Xu, N. et al. Prognostic impact of lipoprotein(a) in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention modified by low density lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin. Chim. Acta. 540, 117217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2023.117217 (2023).

Wang, Z., Yan, X., Fang, L., Tang, J. & Zhang, J. Association between lipoprotein(a), fibrinogen and their combination with all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer-related mortality: Findings from the NHANES. BMC Public. Health. 24(1), 1927. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19443-4 (2024).

Krittanawong, C. et al. Lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice: A guide for the clinician. Prog Cardiovasc. Dis. 79, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2023.07.006 (2023).

Wang, Z., Li, M. & Liu, N. The nonlinear correlation between lipoprotein (a) and the prevalence of aortic valve calcification in patients with new-onset acute myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol. 77(10), 950–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/00015385.2022.2129183 (2022).

Berman, A. N. et al. Lipoprotein(a) and major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with or without baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83(9), 873–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2023.12.031 (2024).

Dai, K. et al. Impact of lipoprotein (a) on long-term outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ. J. 87(10), 1356–1361. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0221 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Association between lipoprotein(a) and long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention for lesions with in-stent restenosis. J. Clin. Lipidol. 17(4), 458–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2023.05.094 (2023).

Zhang, B. et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a novel biomarker for predicting adverse outcomes in ischemic heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1466146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1466146 (2024). Published 2024 Sep 5.

Wang, X. et al. Novel grading system for ischemia–reperfusion injury manifestations in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 19349. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24019-6 (2022). Published 2022 Nov 11.

Li, N. et al. Prognostic impacts of diabetes status and lipoprotein(a) levels in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01881-w (2023).

Miñana, G. et al. Lipoprotein(a) and long-term recurrent infarction after an acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 211, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.10.028 (2024).

Park, J. S. et al. Baseline lipoprotein(a) levels and long-term cardiovascular outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. J. Korean Med. Sci. 38(13), e102. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e102 (2023). Published 2023 Apr 3.

Zhao, L. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is a new prognostic factor in patients with psoriasis and coronary artery disease: A retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 22(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-023-01901-4 (2023).

Kamstrup, P. R., Hung, M. Y., Witztum, J. L., Tsimikas, S. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Oxidized phospholipids and risk of calcific aortic valve disease: The Copenhagen General Population Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 37(8), 1570–1578. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308761 (2017).

Schmidt, K., Noureen, A., Kronenberg, F. & Utermann, G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J. Lipid Res. 57(8), 1339–1359. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R067314 (2016).

Pirro, M. et al. Lipoprotein(a) and inflammation: A dangerous duet leading to endothelial loss of integrity. Pharmacol. Res. 119, 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2017.02.001 (2017).

Jiang, H. et al. Mechanisms of oxidized LDL-mediated endothelial dysfunction and its consequences for the development of atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 925923. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.925923 (2022). Published 2022 Jun 1.

Koschinsky, M. L. & Boffa, M. B. Oxidized phospholipid modification of lipoprotein(a): Epidemiology, biochemistry and pathophysiology. Atherosclerosis 349, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2022.04.001 (2022).

Wang, Z., Xiao, S. & Liu, N. Association of lipoprotein(a) with coronary severity in patients with new-onset acute myocardial infarction: A large cross-sectional study. Clin. Chim. Acta. 540, 117220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2023.117220 (2023).

Varzideh, F., Kansakar, U. & Santulli, G. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular risk: New insights. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. Published Online November. 15. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwae378 (2024).

Vavuranakis, M. A. et al. The trajectory of lipoprotein(a) during the Peri- and early postinfarction period and the impact of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibition. Am. J. Cardiol. 171, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.01.058 (2022).

Sourij, C. et al. Changes in lipoprotein(a) levels in people after ST elevation myocardial infarction-the STEMI-lipids study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(21), 15531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242115531 (2023). Published 2023 Oct 24.

Tsimikas, S. et al. NHLBI working group recommendations to reduce Lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.014 (2018).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation of China (BK20220829), the Double Innovation Doctoral Program of Jiangsu Province (JSSCBS20210087), the Open Project Programme of the Key Base for Standardized Training for Emergency Physicans, Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University (ZDZYJD-JZ-2022-11), and the Talent Development Programme of Southeast University School of Medicine Affiliated Zhongda Hospital (CZXM-GSP-RC131).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qianhui Li, Shuailei Xu and Junxian Shen : Data curation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Software. Qianhui Li: Writing - original draft. Qianhui Li, Shuailei Xu, Junxian Shen and Fengnian Sun: Writing - review & editing. Fengnian Sun: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital affiliated to Southeast University (Approval number: 2023ZDSYLL141-P01). This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Since this was a retrospective study involving existing medical records, direct patient contact was not required, and informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital affiliated to Southeast University.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Xu, S., Shen, J. et al. The nonlinear association between lipoprotein(a) and major adverse cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients with three-vessel disease. Sci Rep 15, 1720 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86154-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86154-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Residual cardiovascular risk in coronary artery disease: from pathophysiology to established and novel therapies

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2026)