Abstract

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) have shown efficacy in clinical trials for slowing chronic kidney disease (CKD) progression, but real-world data in diverse populations are limited. This retrospective study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of SGLT2i versus renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) blockade in CKD patients. Data from Ramathibodi Hospital (2010–2022) were analyzed, including 6,946 adults with CKD stages 2–4, with and without diabetes, who received SGLT2i (n = 1,405) or RAAS blockade (n = 5,541) for at least three months. Patients were matched 1:4 by CKD stage and treatment initiation date. A weighted Cox proportional hazards model with inverse probability weighting assessed the effect on composite major adverse kidney events (MAKEs), including eGFR decline ≥ 40%, progression to CKD stage 5, dialysis initiation, and cardiovascular or kidney death. SGLT2i therapy was associated with a lower risk of composite MAKEs (HR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.36–0.98; P = 0.041) and less frequent progression to CKD stage 5 (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.34–0.80; P < 0.003). Adverse event rates were similar between groups, with lower urinary tract infection incidence in the SGLT2i group. These findings suggest SGLT2i therapy might reduce adverse kidney outcomes in CKD patients, regardless of diabetic status, with a favorable safety profile.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become a significant global health burden, affecting nearly 850 million people worldwide with no signs of abating1,2,3,4. Aging, obesity, and diabetes are key drivers of this growing trend1,5. In CKD management, delaying disease progression and reducing CKD-related mortality remain the primary therapeutic goals. For decades, the cornerstone treatment for patients with proteinuric CKD has been the blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)6,7. These agents have demonstrated established nephroprotective and cardioprotective benefits8,9. However, despite widespread use of RAAS blockade, the global burden of CKD continues to rise.

The introduction of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) has marked a paradigm shift in CKD management. Large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs)10,11,12 have demonstrated that SGLT2i use can slow kidney function decline, decrease the need for kidney replacement therapy (KRT), and reduce the risk of kidney or cardiovascular death in patients with CKD, irrespective of diabetic status. These compelling findings have led to the expansion of SGLT2i use in the 2024 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline, now recommending their use in a broader CKD population with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) greater than 20 ml/min/1.73 m7.

Although RCTs10,11,12 provide valuable insights, limitations inherent to their design, including restricted enrollment criteria and enforced medication adherence, may only partially capture real-world complexities. Comorbidities, variable medication adherence patterns, and drug interactions in real-world settings can significantly affect treatment effectiveness and safety. Previous real-world studies have shown the benefits of SGLT2i in slowing kidney decline and reducing cardiovascular events in diabetic patients13,14,15,16. However, real-world data remains limited for the broader CKD population, particularly non-diabetic individuals. Additionally, safety data from real-world settings in patients with CKD taking SGLT2i therapy is scarce. This knowledge gap warrants further investigation, particularly in middle-income settings.

This study addresses this gap by investigating the comparative effectiveness and safety of SGLT2i therapy versus RAAS blockade in reducing CKD progression and death from kidney or cardiovascular causes in a real-world cohort with CKD stages 2–4, including both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals. By generating real-world data on SGLT2i therapy in CKD, this study aims to inform optimal treatment strategies for a wider range of patients with CKD encountered in everyday clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

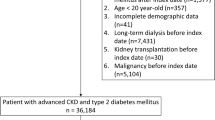

This study was a subset of a retrospective CKD cohort, utilizing real-world data from patients diagnosed with CKD at Ramathibodi Hospital, a university-affiliated tertiary care center and major referral hospital in Bangkok, Thailand, from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2022 (Fig. 1). CKD diagnoses were ascertained from a de-identified electronic database using International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes for identifying CKD cases, including ICD-9 codes (3895, 3927, 3942, 3943, 3995, and 5498) and ICD-10 codes (N18.0-N18.9). These codes were used with the 2012 KDIGO criteria, which define CKD as an eGFR persistently below 60 ml/min/1.73 m² for at least two measurements separated by more than three months. Persistent hematuria or proteinuria were not included as diagnostic criteria due to substantial missing data.

Patients were eligible if they (i) had any CKD stage from any cause and (ii) were prescribed either SGLT2i or RAAS blockade for more than three months since January 2015 (as per the initial availability of SGLT2i in Thailand). Patients were excluded if they had (i) less than one eGFR measurement within one year after the index date or (ii) type 1 diabetes mellitus. The index date was defined as the initial prescription date of either SGLT2i (the SGLT2i group) or RAAS blockade (the control group). Patients were followed until the first occurrence of any primary outcome component, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study if event-free.

Sample size calculation

In the DAPA-CKD trial12, which investigated the effect of dapagliflozin on CKD progression, the placebo group experienced a composite kidney outcome rate of 14.5% compared to 9.2% in the dapagliflozin group over the follow-up period. Therefore, to detect a difference of 5% with a power of 80% and a significance level (alpha) of 0.05, a minimum of 2,487 patients (415 SGLT2i and 2,072 RAAS blockade) for a ratio of 1:5 or 2,150 patients (430 SGLT2i and 1,720 RAAS blockade) for a ratio of 1:4 would be required in our study design.

Treatments, outcomes, and covariates

Patients in the SGLT2i group received any FDA-approved SGLT2i therapy for a minimum of three months, alongside standard CKD care and other indicated treatments. RAAS blockade was allowed if initiated before or switched to during follow-up, based on clinical indications. The control group received RAAS blockade for at least three months, along with standard CKD care and other indicated medications. To minimize potential temporal biases related to changing treatment practices, RAAS blockade initiation dates were matched to SGLT2i initiation dates within a one-year window.

In Thailand, three main insurance schemes exist: The Civil Servant Medical Benefit Scheme (CSMBS), Social Security System (SSS), and Universal Coverage Scheme (UCS). SGLT2i is covered by CSMBS for all FDA-approved indications (including both diabetic and non-diabetic conditions such as CKD), while coverage under SSS was limited, and UCS did not reimburse SGLT2i unless self-paid.

The primary outcome was the time to the first occurrence of a composite major adverse kidney event (MAKE) in patients receiving SGLT2i compared to those receiving RAAS blockade over a seven-year follow-up period. The composite MAKE included: (1) a sustained decline in eGFR of at least 40% from baseline (confirmed by a subsequent measurement after four weeks); (2) progression to CKD stage 5 (eGFR < 15 ml/min/1.73 m² for more than four weeks); (3) initiation of KRT lasting longer than three months; or (4) death from kidney or cardiovascular causes. Patients were censored at the time of loss to follow-up or at the study’s end if they remained event-free. The time to the composite MAKE occurrence was calculated as the interval between the treatment start date and either the date of the first MAKE event or the last follow-up date. Secondary outcomes included the individual components of the composite endpoint.

Safety outcomes included rates of urinary tract infections (UTIs), Fournier gangrene, hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), acute kidney injury (AKI), hypotension, bone fractures, and limb amputation.

Baseline covariate data, including comorbidities and causes of death, were retrieved using ICD-9/10 codes. Laboratory values were extracted from laboratory databases for baseline and follow-up visits.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics by treatment groups are presented as percentages for categorical variables and mean with standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables based on normality. These corresponding variables were compared using a Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) or student’s T-test (or Mann-Whitney U tests) as appropriate, respectively.

A propensity score (PS) analysis was used to balance covariates between treatment groups (SGLT2i vs. RAAS blockade) through the following steps: First, we developed a treatment model (TM) including key covariates known to influence treatment allocation: sex, age, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular comorbidities, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and baseline eGFR. Covariate balance was achieved when the weighted standardized mean differences did not exceed 0.2. The PS, representing the probability of receiving each treatment, was then calculated.

Second, we constructed the MAKE outcome model using a cause-specific hazard model, weighted by the inverse probability of treatment allocation (i.e., PS), accounting for competing risks of death from other causes. We then estimated the probabilities of developing composite MAKEs, along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), for each treatment group. In addition, we estimated cause-specific hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs, adjusting for relevant factors identified in univariate analyses (P-value < 0.05) or established CKD progression risk factors (e.g., age, sex, diabetes, baseline eGFR).

Furthermore, the incidence rate of each individual MAKE component was estimated separately using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using the log-rank test. Finally, the cumulative incidence of common adverse events was estimated and compared between the SGLT2i and RAAS blockade groups using risk ratios and 95% CIs. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the Chi-square test. All data analyses and visualizations were performed using Stata 18.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was set at a P-value < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (COA. MURA2021/631 and COA. MURA2023/246). The requirement for written, informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University due to the retrospective nature of the study and use of de-identified data. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

From an initial cohort of 63,180 patients with CKD (all stages), we excluded 20,838 with stage 1 or stage 5 CKD and those meeting additional exclusion criteria detailed in Fig. 1. We further excluded 635 patients who initiated treatment after stage 5 onset. Of the remaining 23,172 patients, SGLT2i users were matched to RAAS blockade users, resulting in a final analysis cohort of 1,405 in the SGLT2i group and 5,541 in the RAAS blockade group (approximate a 1:4 ratio based on medication initiation date and baseline CKD stage). This sample size provides approximately 99% power to detect a 5% risk difference of MAKEs. The median (IQR) follow-up duration was 27.3 (13.6–42.0) months.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study participants. Patients treated with SGLT2i were significantly younger (mean [SD] age 69.7 [9.8] years vs. 71.4 [11.6] years, P < 0.001) and had a higher prevalence of T2D (94.0% vs. 43.7%, P < 0.001). Mean [SD] HbA1c levels were also significantly higher in the SGLT2i group (7.7 [1.5]% vs. 6.5 [1.3]%, P < 0.001). Both groups were predominantly composed of patients with CKD stage 3. The SGLT2i group had a slightly higher mean [SD] eGFR at enrollment compared to the RAAS blockade group (52.3 [11.3] ml/min/1.73m2 vs. 51.2 [11.6] ml/min/1.73m2, P = 0.003) and a significantly greater proportion of patients covered under the CSMBS (74.8% vs. 58.8%, P < 0.001). Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) data was missing for a substantial portion (82%) of the cohort.

Of the 1,405 patients in the SGLT2i group, 16.4% (n = 231) had never used RAAS blockade, 78.3% (n = 1,099) had previously used RAAS blockade but discontinued it before initiating SGLT2i, and 5.3% (n = 75) switched from SGLT2i to RAAS blockade during follow-up. All patients in the RAAS blockade comparison group remained SGLT2i-naïve throughout the study.

Treatment effect models

A logistic regression model estimated the probability of receiving SGLT2i or RAAS blockade. Before PS weighting, absolute standardized mean differences (ASMDs) between groups ranged from − 0.12 to 1.30, indicating some baseline imbalance. PS weighting effectively balanced these covariates, minimizing ASMDs to -0.03 to 0.16 and achieving variance ratios near 1 (see Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Effects of SGLT2i on composite MAKEs

During the follow-up period, 109 (7.7%) patients in the SGLT2i group and 459 (8.3%) in the RAAS blockade group experienced MAKEs. The cumulative incidence of composite MAKEs was lower among patients receiving SGLT2i therapy compared to those on RAAS blockade (2.5 vs. 2.9 per 1000 patient- months) (Supplementary Table S2). Following adjustment for PS and other factors, SGLT2i therapy was associated with a 41% lower risk of composite MAKEs compared to those receiving RAAS blockade (adjusted HR: 0.59; 95% CI: 0.36–0.98; P = 0.041) (Table 2). This difference was evident in a progressively widening gap in event-free probability between the two groups over time (Fig. 2). At 36 months, the probability of remaining free of MAKEs was 4% higher in the SGLT2i group (0.95 vs. 0.91), increasing to 6% at 60 months (0.92 vs. 0.86). The proportional hazards assumption was met for this event-free curve (Chi-square = 0.004; P = 0.947).

PS-adjusted multivariable analysis identified other independent predictors of MAKEs (Table 2). Females with a history of cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, and anti-arrhythmic medication use were more likely to experience MAKEs. Conversely, higher baseline eGFR and older age were associated with a lower risk of composite MAKEs.

Effects of SGLT2i on individual components of MAKEs

Kaplan-Meier analysis of individual MAKE components revealed a significant 48% reduction in the risk of progression to CKD stage 5 for patients receiving SGLT2i compared to those on RAAS blockade (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.34–0.80; P = 0.003) (Fig. 3b). While the Kaplan-Meier curves suggest potential benefits of SGLT2i therapy in reducing the risk of substantial eGFR decline ≥ 40% from baseline (HR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.69–1.11; P = 0.265) and delaying the need for KRT (HR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.53–1.11; P = 0.164), these trends did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3a and c). There was no significant association between SGLT2i treatment and death from kidney or cardiovascular causes (HR: 1.66; 95% CI: 0.90–3.05; P = 0.102) (Fig. 3d). The proportional hazard assumptions were met for CKD stage 5 (Fig. 3b, Chi-square = 0.20; P = 0.653) and KRT (Fig. 3c, Chi-square = 0.01; P = 0.924), but not for ≥ 40% eGFR decline (Fig. 3a, Chi-square = 11.4; P = 0.001) and death (Fig. 3d, Chi-square = 8.07; P = 0.005).

Supplementary Figure S2 depicts changes in eGFR over five years. Both groups experienced a decline: from 48.19 to 39.54 mL/min/1.73 m² in the SGLT2i group and from 47.31 to 38.66 mL/min/1.73 m² in the RAAS blockade group. Mixed-effect linear regression analysis revealed a significantly higher overall-mean eGFR in the SGLT2i group, with a difference of 0.88 mL/min/1.73 m² (95% CI: 0.07–1.70; P = 0.034).

Effects of SGLT2i and other risk factors on death from non-kidney, non-cardiovascular causes (competing events)

SGLT2i therapy did not increase the risk of death from non-kidney, non-cardiovascular causes compared to RAAS blockade (see Supplementary Tables S3-S4). Independent risk factors associated with these deaths included advanced age (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.04–1.08; P < 0.001), peripheral vascular disease (HR: 3.12; 95% CI: 1.44–6.79; P = 0.004), and higher blood glucose levels (HR: 1.010; 95% CI: 1.004–1.016; P = 0.001).

Comparison of adverse events between SGLT2i and RAAS blockade

Table 3 summarizes the cumulative incidence of common adverse events in the SGLT2i and RAAS blockade groups. UTIs and AKI were the most frequent events. Notably, treatment with SGLT2i was associated with a 27% lower risk of UTIs than RAAS blockade (relative risk [RR]: 0.73; 95% CI: 0.56–0.94; P = 0.013). Rates of other adverse events, including AKI, hypoglycemia, bone fractures, hypotension, and Fournier gangrene, were comparable between groups.

Discussion

This real-world study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of SGLT2i therapy, predominantly as monotherapy, compared to RAAS blockade in a diverse population of patients with CKD stages 2–4, including both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals. Our findings suggest that SGLT2i therapy was associated with a 41% lower risk of MAKEs during follow-up compared to RAAS blockade. This association persisted after adjusting for diabetic status and other established CKD risk factors. Furthermore, SGLT2i therapy conferred a substantial benefit, with a 48% lower risk of progression to CKD stage 5. Contrary to initial safety concerns, this study found a lower incidence of UTIs in the SGLT2i group compared to RAAS blockade, with comparable rates of other adverse events between the two groups. These real-world findings complement existing evidence from RCTs by offering additional insights into the effectiveness and safety of SGLT2i therapy in routine clinical practice.

Our findings suggest that SGLT2i therapy might offer potential benefits in managing CKD in real-world settings, particularly when added to standard care. The 41% reduction in the risk of MAKEs aligns with the evidence from large-scale RCTs 10,11,12,17,18,−19, which reported a 14–39% decrease in composite kidney events for SGLT2i therapy compared to placebo in patients with CKD. The observed benefit persisted despite potential variations in medication adherence, a common real-world challenge20, suggesting its effectiveness in clinical practice. Our findings are consistent with similar risk reductions (6–76%) reported in real-world studies comparing SGLT2i therapy to other anti-diabetic medications in diabetic patients with CKD14,16,21,22. This consistency across real-world data, RCTs, and other studies strengthens the rationale for broader SGLT2i use across the CKD spectrum, regardless of diabetic status.

Our analysis also revealed that SGLT2i therapy significantly reduced the risk of progressing to CKD stage 5. However, this benefit appeared more modest compared to the study by Lui et al.16, which focused solely on diabetic patients. Our inclusion of a broader CKD population might explain this difference. Similarly, subgroup analysis from the EMPA-KIDNEY trial11 reported a more pronounced benefit of SGLT2i therapy on kidney outcomes in diabetic patients with CKD compared to non-diabetic patients. While trends suggested potential benefits for SGLT2i therapy in slowing eGFR decline and delaying KRT initiation, these findings did not reach statistical significance. Although the proportional hazards assumption was satisfied for the composite MAKE endpoint, it was violated for certain individual components, including a ≥ 40% eGFR decline and death from kidney or cardiovascular causes. This may be due to the limited number of individual events and the relatively short median follow-up period of 27 months. Further research involving larger cohorts and extended follow-up durations are necessary to assess these longer-term outcomes.

We identified several independent risk factors for the composite MAKE endpoint in patients with CKD, which align with established associations between CKD and cardiovascular comorbidities23,24. Unexpectedly, older age was associated with a lower risk of MAKEs. Competing risks might explain these seemingly paradoxical findings. Older adults with advanced CKD may be less likely to experience MAKEs due to a higher overall mortality risk from non-kidney and non-cardiovascular causes25. Additionally, concerns about frailty or co-existing geriatric conditions in this population might lead to less aggressive treatment approaches, potentially influencing the observed risk of MAKEs26.

Regarding safety, UTIs were the most common adverse event. Notably, UTIs occurred more frequently in the RAAS blockade group than in the SGLT2i group. This finding corroborates previous trials11,27,28 and real-world studies29,30,31, suggesting no significant increase in UTI risk with SGLT2i in patients with CKD. This is reassuring, given concerns raised by FDA warnings32. Selection bias is a potential limitation, as the prescription of SGLT2i might be more cautious for patients with a history of UTIs. There were no other significant safety concerns, including DKA, AKI, Fournier gangrene, or bone fractures. Our data support the generally favorable safety profile of SGLT2i therapy observed in previous studies for patients with CKD11,12,29. However, personalized medicine approaches remain crucial to optimize treatment benefits while considering patient-specific risk factors for side effects.

Our retrospective design with PS matching has several limitations. The real-world nature of the study precludes establishing direct causal relationships between SGLT2i therapy and outcomes. While temporal matching and PS weighting adjusted for key covariates (demographics, baseline kidney function, diabetes, and cardiovascular comorbidities), residual confounding and selection bias remain possible. Treatment selection was influenced by clinical judgment, patient preferences, and insurance coverage. Unmeasured confounders, such as physician prescribing patterns, patient adherence, and evolving clinical practices, may have impacted the observed benefits, especially regarding MAKE risk reduction. Real-world (or found) data limitations, such as variable timing of eGFR measurements, hindered systematic acute and chronic slope analyses commonly performed in RCTs. Reliance on ICD codes without consistent urinary markers may have introduced inaccuracies in the classification of CKD stages 1–2. The single-center design at a tertiary care hospital and variations in insurance coverage may limit generalizability to primary care settings or healthcare systems with differing SGLT2i access. Furthermore, while most SGLT2i patients were RAAS blockade-naïve or had discontinued prior use, 5% switched to RAAS blockade during follow-up. This complicates benefit attribution and limits the precise determination of SGLT2i’s independent effects in a real-world setting. Future multicenter studies with standardized medication protocols, comprehensive urine data collection, and diverse populations across various healthcare systems are needed to confirm the independent effects of SGLT2i therapy in CKD management.

Despite these limitations, this study adds valuable real-world evidence supporting SGLT2i therapy in CKD management. By including both diabetic and non-diabetic patients and employing competing risk analysis, we have enhanced the relevance and robustness of our findings. Furthermore, this study provides important safety data on SGLT2i use in a real-world setting, where such data was previously limited29. These findings can help guide clinical decision-making in everyday practice.

This real-world study might support the expanded use of SGLT2i therapy in patients with CKD stages 2–4, regardless of diabetic status. SGLT2i treatment was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of MAKEs compared to RAAS blockade in diabetic and non-diabetic patients, and showed potential in delaying progression to CKD stage 5. Along with a favorable safety profile, these findings align with the 2024 KDIGO guidelines recommending broader application of SGLT2i in CKD management7. Future studies with longer follow-up periods and comprehensive urine data collection are needed to further validate these results and refine treatment strategies for patients with CKD.

Data availability

The datasets collected and analyzed during this work are not publicly available; however, anonymized data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DPP4 inhibitors:

-

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GLP−1 receptor agonist:

-

Glucagon−like peptide-1 receptor agonists

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- RAAS:

-

Renin−angiotensin−aldosterone system blockade

- SGLT2i:

-

Sodium-glucose cotransporter−2 inhibitors

References

Bikbov, B. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: Asystematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395, 709–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30045-3 (2020).

Rhee, C. M., Kovesdy, C. P. & Epidemiology Spotlight on CKD deaths-increasing mortality worldwide. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 11, 199–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph201525 (2015).

Stanifer, J. W., Muiru, A., Jafar, T. H. & Patel, U. D. Chronic kidney disease in low- and middle-income countries. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 31, 868–874. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfv466 (2016).

Jager, K. J. et al. A single number for advocacy and communication-worldwide more than 850 million individuals have kidney diseases. Nephrol. Dial Transpl. 34, 1803–1805. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfz174 (2019).

Matsushita, K. et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: Acollaborative meta-analysis. Lancet 375, 2073–2081. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60674-5 (2010).

Lewis, E. J., Hunsicker, L. G., Bain, R. P. & Rohde, R. D. The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. The collaborative Study Group. N Engl. J. Med. 329, 1456–1462. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199311113292004 (1993).

KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 105, S117–s314, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018 (2024).

Wright, J. T. Jr. et al. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: R esults from the AASK trial. JAMA 288, 2421–2431. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.19.2421 (2002).

Lewis, E. J. et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl. J. Med. 345, 851–860. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa011303 (2001).

Perkovic, V. et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl. J. Med. 380, 2295–2306. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1811744 (2019).

Herrington, W. G. et al. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl. J. Med. 388, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2204233 (2023).

Heerspink, H. J. L. et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl. J. Med. 383, 1436–1446. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024816 (2020).

Heerspink, H. J. L. et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: Apre-specified analysis from the DAPA-CKD randomized controlled trial. Eur. Heart J. 42, 1216–1227. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab094 (2021).

Heerspink, H. J. L. et al. Kidney outcomes associated with use of SGLT2 inhibitors in real-world clinical practice (CVD-REAL 3): Amultinational observational cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(19)30384-5 (2020).

Nagasu, H. et al. Kidney outcomes Associated with SGLT2 inhibitors Versus other glucose-lowering drugs in real-world clinical practice: The Japan chronic kidney Disease Database. Diabetes Care. 44, 2542–2551. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-1081 (2021).

Liu, A. Y. L. et al. A real-world study on SGLT2 inhibitors and diabetic kidney disease progression. Clin. Kidney J. 15, 1403–1414. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfac044 (2022).

Zinman, B. et al. Cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl. J. Med. 373, 2117–2128. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 (2015). Empagliflozin.

Wiviott, S. D. et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl. J. Med. 380, 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1812389 (2019).

Neuen, B. L. et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for the prevention of kidney failure in patients with type 2 diabetes: Asystematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7, 845–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30256-6 (2019).

Cai, J., Divino, V. & Burudpakdee, C. Adherence and persistence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus newly initiating canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, dpp-4s, or glp-1s in the United States. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 33, 1317–1328. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2017.1320277 (2017).

Forbes, A. K. et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and kidney outcomes in real-world type 2 diabetes populations: Asystematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 25, 2310–2330. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.15111 (2023).

Siriyotha, S. et al. Clinical effectiveness of second-line antihyperglycemic drugs on major adverse cardiovascular events: An emulation of a target trial. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1094221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1094221 (2023).

Yang, J. G. et al. Chronic kidney disease, all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality among Chinese patients with established cardiovascular disease. J. Atheroscler Thromb. 17, 395–401. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.3061 (2010).

Elsayed, E. F. et al. Cardiovascular disease and subsequent kidney disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 167, 1130–1136. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.11.1130 (2007).

Singh, A. K. et al. Causes of death in patients with chronic kidney disease: insights from the ASCEND-D and ASCEND-ND cardiovascular outcomes trials. Eur. Heart J. 43 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac544.1053 (2022).

Wilson, T. et al. Treatment preferences for Cardiac procedures of patients with chronic kidney disease in Acute Coronary Syndrome: design and pilot testing of a Discrete Choice Experiment. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 8, 2054358120985375. https://doi.org/10.1177/2054358120985375 (2021).

Puckrin, R. et al. SGLT-2 inhibitors and the risk of infections: Asystematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Diabetol. 55, 503–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-018-1116-0 (2018).

Zinman, B. et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl. J. Med. 373, 2117–2128. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 (2015).

Chan, G. C., Ng, J. K., Chow, K. M. & Szeto, C. C. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce adverse kidney and cardiovascular events in patients with advanced diabetic kidney disease: Apopulation-based propensity score-matched cohort study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 195, 110200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110200 (2023).

Dave, C. V. et al. Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 inhibitors and the risk for severe urinary tract infections: APopulation-based Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 171, 248–256. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-3136 (2019).

Sarafidis, P. A. & Ortiz, A. The risk for urinary tract infections with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: no longer a cause of concern? Clin. Kidney J. 13, 24–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfz170 (2019).

Administration., U. S. F. & a., D. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA Revises Labels of SGLT2 Inhibitors for Diabetes to Include Warnings About too much Acid in the Blood and Serious Urinary Tract Infections; (2015). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm475463.htm;published 4 December ; last accessed 24 April 2024., http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm475463.htm (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT) N42A640323. The study funder had no role in the design or conduct of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.I., A.T., and S.B. conceptualized the study and developed the methodology; A.T., N.U., S.B., S.H., and W.P. performed the formal analysis; S.B. and S.H. prepared the original draft; A.I., A.T., G.M., J.A., N.U., S.B., S.H., and W.P. contributed to the review and editing; S.B. and N.U. handled visualization; A.T. secured funding. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hunsuwan, S., Boongird, S., Ingsathit, A. et al. Real-world effectiveness and safety of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors in chronic kidney disease. Sci Rep 15, 1667 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86172-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86172-y