Abstract

The single nucleotide polymorphism in NOD2 (rs2066847) is associated with conditions that may predispose to the development of gastrointestinal disorders, as well as the known BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants classified as risk factors in many cancers. In our study, we analyzed these variants in a group of patients with pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer to clarify their role in pancreatic disease development. The DNA was isolated from whole blood samples of 553 patients with pancreatitis, 83 patients with pancreatic cancer, 44 cases of other pancreatic diseases, and 116 healthy volunteers. The NOD2 (rs2066847), BRCA1 (rs80357914) and BRCA2 (rs276174813) were genotyped. The statistically significant 3-fold increased risk of pancreatic cancer was detected among the patients with rs2066847 polymorphism (OR = 2.77, p-value = 0.019). We did not find the studied polymorphisms in BRCA1 (rs80357914) and BRCA2 (rs276174813). However, the adjacent polymorphisms have been detected only in patients with pancreatic diseases. The studied variant in NOD2 occurs more frequently in pancreatic patients and significantly increases the risk of pancreatic cancer. It can be considered as a genetic risk factor that predisposes to cancer development. The analyzed regions in BRCA1 and BRCA2 may be a potential target in further search for a genetic marker of pancreatic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

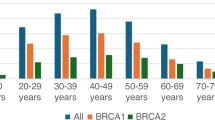

Pancreatitis, regardless of whether it is acute or chronic, always carries the risk of malignant transformation leading to the development of one of the most dangerous and most difficult to treat and diagnose cancers: pancreatic cancer1,2,3. Genetic background plays an important role here, but as is widely known, many genes are involved in the metabolic pathways of the pancreas. The search for genetic markers differentiating patients with pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis would be a huge achievement in advancing the development of personalized therapies and prevention regimens against the development of these diseases4,5. Significant progress in oncological treatment was made after the development of modern diagnostics and the introduction of molecular drugs acting specifically against the molecular change in the cancer cell6,7,8. The recent development of precision medicine is crucial because, based on extensive data on epidemiology, clinical parameters, family history, and genetic analyses, it can propose various strategic models for a given pancreatic disease9. An association between germline single nucleotide variants (SNV) of many genes and an increased risk of pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis has already been proven10,11,12,13. However, no clear differences have yet been identified because the same variants are often involved in different pathomechanisms of pancreatic diseases. Additionally, the influence of hereditary susceptibility to pancreatic cancer is enhanced by environmental factors such as smoking or alcohol consumption, which favors the formation of pathogenic somatic mutations leading to the development of cancer14. The literature often identifies germline mutations of many genes that increase the risk of pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer15,16,17. This entails an increased risk of loss of heterozygosity or loss of function in somatic cells (mostly in the KRAS, CDKN2A, TP53 and SMAD4/DPC4) often identified at different stages of the pancreatic cancer development18,19,20,21,22. Germline BRCA1/2 mutations occur in 4–7% of pancreatic cancers and they are the most common mutated genes in familial pancreatic cancer, however, mutations in BRCA2 are more common (5–17% of pancreatic cancer) and increase the risk of disease by 3.5–10 times22. Currently, the NCCN guidelines recommend testing all patients with pancreatic cancer for the presence of germline BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations. This is related to attempts at early detection of pancreatic cancer in patients’ relatives by recommending screening. Other high-risk factors include, among others: having a first-degree relative with pancreatic cancer, diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome or Lynch syndrome, detection of a CDKN2A mutation23. Recently, the role of other genes has been reported, e.g. according to The Cancer Genome Atlas, CHEK2 gene mutations are observed in 0.7% of pancreatic cancer cases and it probably interacts with the BRCA gene, deepening DNA repair disorders and contributing to cancer development24. Another gene that is recently attracting increasing attention of clinical geneticists is NOD2. This gene is associated with inflammatory bowel disease and pancreatitis. Recurrent pancreatitis can lead to cancer development by stimulating cell proliferation, inducing DNA damage, and stimulating angiogenesis. The conducted analyses for the NOD2 mutations among the patients with pancreatic cancer have not revealed any significant correlations yet, but only served as the preliminary studies25. This well-founded hypothesis needs to be further verified and explored on a bigger study group.

The aim of the study was to analyze the occurrence of three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) in NOD2 and BRCA1, BRCA2 genes among patients with acute pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer, in comparison to healthy volunteers. The results are an important scientific contribution to the knowledge on pathomechanisms of pancreatic diseases and may have influence on the development of predictive schemes.

Results

A total of 796 DNA samples was used for the analysis of the selected single nucleotide variants in the 11th exon of NOD2 (rs2066847), 2nd exon of BRCA1 (rs80357914), and 10th exon of BRCA2 (rs276174813). Research material was isolated from 680 clinical patients and 116 healthy volunteers. The patients were distinguished based on the type of the diseases: acute and chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and other pancreatic diseases. In further differentiation, the etiological factor of pancreatitis was considered, however in some cases it could not be identified. The analyses were not performed for all samples due to technical problems (lack of research material or PCR product, lack of HRM analysis/Sanger sequencing of sufficient quality). The final number of samples for which genetic analysis was performed is shown in Table 1. Due to the small number of cases in some factors of acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis, the following groups were finally distinguished for statistical analysis: idiopathic, biliary, alcoholic, other (postpartum, hyperlipidemia, drug-related, cancer-related, autoimmunological) and the group not diagnosed with an etiological factor.

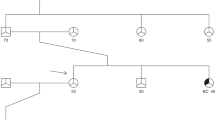

The allele frequencies in the studied group were determined, alongside the analysis of the frequencies of the investigated genetic variants in both global and European populations, based on the ALFA Allele Frequency Database (NCBI) and shown in Table 2 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). For the NOD2 gene variant (rs2066847), the global allele frequency of the duplication variant is reported as 0.08544, with a notably higher prevalence in European populations, where the frequency is 0.09429. In the studied population, the allele frequency was lower and amounted to 0,0516 (Table 2). Regarding the BRCA1 gene variant (rs80357914), the global allele frequency of the CT variant is 0.00065, whereas in European populations, it is slightly lower at 0.00051. For the BRCA2 gene variant (rs276174813), data from the gnomAD Study were utilized. According to the database, the global allele frequency for the delCTTAT variant is 0.000004, while in European populations, the frequency is slightly higher at 0.000008. In our study, there were no cases of both variants. Further statistical analysis included the assessment of variant frequencies in individual study groups, as well as for the etiological factor contributing to the disease occurrence. It should be mentioned that the frequency of alleles in specific populations is often lower than the global average due to differences in genetic diversity and allele distribution across regions. An interesting result was revealed for rs2066847 of NOD2 gene (Table 3). This polymorphism occurred least frequently among the control group and patients with “other diseases” (6% of participants). Considering the type of pancreatitis, the participants with the rs2066847 polymorphism seem to be more predisposed to chronic pancreatitis (CP), the prevalence of the polymorphism was 4% higher in this group compared to acute pancreatitis (AP) (10% of AP patients), but the difference was not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact two sided), probably due to due to the small size of the CP group (n = 21). In the AP group of patients, the polymorphism occurred least frequently in the case of an idiopathic factor (7% of patients), and most frequently in the case of alcoholic acute pancreatitis (12.76% of AP-Alc). This prevalence was not statistically significant compared to any other group of patients (chi-square or Fisher’s exact two sided). In the AP-Alc group, polymorphism was detected in 18 patients: 17/132 males with AP-Alc and only one female among 12 females with AP-Alc. However, this difference was also not statistically significant (Fisher’s exact two sided). The highest prevalence of the tested polymorphism was revealed in the group of patients with pancreatic cancer (16.86% of patients). In general, there is a tendency for the number of patients with the polymorphism to increase as the severity of pancreatic disease increases (Fig. 1). The statistically significant three-fold increased risk of pancreatic cancer was detected among the patients with rs2066847 polymorphism (OR 2.77, 95% CI 1.20–6.42; RR = 3.13, 95% CI 1.23–7.94; p-value = 0.019, Fisher’s exact test, two-sided). When comparing the occurrence of the tested genetic polymorphism between the remaining groups, no correlation was found (Tables 3 and 4).

The occurrence of NOD2 polymorphism (rs2066847) in particular groups of participants: control healthy volunteers, AP and CP patients with acute or chronic pancreatitis, PC pancreatic cancer, PD pancreatic diseases (AP, CP, PC), OD other disease, positive percentage of patients with rs2066847, negative percentage of patients without rs2066847.

The analysis of the genetic polymorphism was also performed considering the sex of the studied participants (Table 3). The polymorphism was observed in 2% more males than females, as well as in the case of pancreatic cancer—the polymorphism occurred almost twice as often in men. However, the difference was not statistically significant, probably due to the size of the groups.

In the case of BRCA1 and BRCA2, we did not identify the studied single nucleotide polymorphisms in any sample. However, all samples that showed a different curve in the HRM-PCR reaction (n = 13) revealed different single nucleotide variants after sequencing (Table S2). All these samples belonged to patients with pancreatic disease—84.6% of the patients had acute pancreatitis, one patient had pancreatic cancer, and one had another pancreatic disease. Within these polymorphisms, 3 different ones have been identified for BRCA1 (rs80357031, rs766004110, rs80356839), and 4 different for BRCA2 (rs80358475, rs28897710, rs56328701, rs2137474144). Only one of these samples had the studied NOD2 polymorphism. These genetic variants are classified as nonpathogenic. In order to assess the sensitivity of the method, we randomly sequenced PCR products without changes in the HRM curve. For BRCA1 and BRCA2, 11 and 15 samples, respectively. Most samples did not show polymorphic changes, but it should be emphasized that these methods are not intended to identify any change but have been optimized for the detection of rs80357914 and rs276174813.

Discussion

Pancreatic diseases are a serious health, social and economic problem worldwide, due to their often-severe course, complications, and high risk of recurrence26,27. Globally, the incidence of acute pancreatitis ranges from 30 to 40 cases per 100,000 individuals annually, with some regions in Europe reporting rates as high as 100 cases per 100,000 individuals28,29. In contrast, the average global incidence of pancreatic cancer is 4.9 cases per 100,000 individuals, while in Europe, the rates are higher, reaching 8–12 cases per 100,000 individuals30. Considering the relatively high incidence of pancreatitis, which is also etiological factors of pancreatic cancer, multifactorial etiology of pancreatic diseases and the difficulties in prevention and treatment, the problem is undeniably important and requires further research. They affect not only the organ itself, but the whole organism, limiting the efficient functioning of a person in society, thus increasing the cost of maintaining the individual and reducing the productivity of society. The most important are acute and chronic pancreatitis and malignant and non-malignant pancreatic tumours16,31,32. Pancreatic diseases pose difficulties not only for efficient diagnosis but also for the development of effective methods of prevention and prediction. The reason for this is the multifactorial and polygenic nature of these diseases33,34,35. The specific and crucial genes for the pancreas show activity that is not remarkably tissue-specific, but also highly inducible. This is why it is so difficult to find clear pathways leading to a given pancreatic disease, especially when it comes to inflammation and cancer36. Many genetic polymorphisms correlated with pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer have already been detected, and new ones are still being revealed9,37. Progress in genetic research and the increase in interest in this area provide a great opportunity to develop predictive schemes for the development of pancreatic disease and to propose new therapeutic methods38,39,40. The presented results of our work constitute an important contribution of an additional polymorphism that significantly increases the risk of pancreatic cancer. We paid attention to the three genes already mentioned and well known in the development of cancers and other related diseases, but we focused particular attention on selected clinically important genetic polymorphisms: rs2066847 of NOD2, rs80357914 of BRCA1, and rs276174813 of BRCA2. Recent studies suggest that BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations affect cellular responses not only through DNA repair defects but also by altering immune signaling pathways. For instance, BRCA1 mutations can dysregulate NF-κB signaling, a pathway also influenced by NOD2 activity. NF-κB is critical in immune responses and inflammation, which are processes where NOD2 plays a key role. Dysregulated NF-κB activity has been linked to cancer development and progression in BRCA-mutated cells. This overlapping impact on NF-κB suggests a possible indirect connection between BRCA1/BRCA2 and NOD2 through immune regulation and inflammatory signaling pathways41,42. Additionally, NOD2’s role in autophagy and cellular stress responses, mechanisms also implicated in BRCA-related tumor suppression, provides another avenue for potential interaction. Aberrations in these shared pathways might contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of cancer etiology, particularly in inflammation-driven cancers42.

NOD2 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2) known also as the CARD15 gene is located on chromosome 16q12.1 in humans and it encodes a pattern recognition receptor, which recognizes the conserved motifs in bacterial peptidoglycan and is involved in apoptosis by activating the NF-κB protein43,44. Mutations in this gene have been associated with many inflammatory diseases, for example, Crohn’s disease, Blau syndrome, severe pulmonary sarcoidosis45,46. as well as cancers in the colon, ovary, breast, lung, larynx, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma and many others47,48,49,50. Three NOD2 polymorphisms are of particular importance: NOD2 (NM_001370466.1): c.2023 C > T p.(Arg675Trp) (rs2066844), NOD2 (NM_001370466.1): c.2641G > C p.(Gly881Arg) (rs2066845) and NM_022162.3(NOD2): c.3019dup p.(Leu1007fs) (rs2066847) due to their association with increased risk of gastrointestinal cancers, but not with pancreatic cancer51. The last one is frameshift mutation NOD2 (NM_022162.3): c.3019dup p.(Leu1007fs) (rs2066847) in exon 11 and results in a prematurely truncated protein predicted to reduce its functional efficiency. This polymorphism was strongly correlated with Crohn’s Disease52,53. There is evidence that the pathophysiology of the pancreas is associated with inflammatory bowel diseases, in particular Crohn’s disease54,55, therefore, the role of NOD2 and rs2066847 polymorphism seems particularly interesting at this point. Contrary to previous reports, we have shown for the first time this polymorphism clearly correlates with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer − 3 times higher risk (Table 3) and shows a trend of increasing cases of pancreatic disease with an increasing number of mutations in the studied groups of participants (Fig. 1). Congruent studies were conducted by Nej et al.25; they showed a similar frequency of this polymorphism occurrence in healthy individuals (7%) and families with a history of pancreatic cancer (14%), but they did not confirm the association with an increased risk of familial pancreatic cancer, probably due to the small size of the study groups. We would like to mention that in our research we noticed the highest prevalence of polymorphism in the AP-Alc group compared to idiopathic AP cases, which can suggest a potential interaction between genetic predisposition and environmental factors, such as alcohol consumption. These results are consistent with previous studies indicating that NOD2 mutations may modulate the response to alcohol-induced injury56. NOD2 and the aforementioned rs2066847 should be investigated further because of their reasonable association with inflammatory bowel and pancreatic diseases.

Initially, in the case of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, the analysis was aimed at detecting two polymorphisms: rs80357914 and rs276174813, which have clinical importance (pathogenic) for breast and ovarian cancers55. BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are tumor suppressor genes that are primarily involved in cell cycle control, DNA repair pathways, and regulation of apoptosis. They are expressed in various cells, therefore mutations in these genes may predispose to multi-organ cancers, mostly including breast and ovary but also others such as colon, and prostate. There is evidence that mutations in these genes may also increase the risk of pancreatic cancer57. The primary research including homogenic populations indicated the germline mutation rates in pancreatic cancer cases ranged from 1 to 11% for BRCA1 and 0–17% for BRCA258,59. More recent studies that used panel testing confirm the presence of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants up to 3% for BRCA1 and up to 6% for BRCA2 among patients with pancreatic cancers60,61. Nevertheless, single nucleotide polymorphisms in these genes are common and they are often associated with a founder effect62,63,64. The rs80357914 of BRCA1 represents c.68_69delAG frameshift mutation in codon 23 of exon 2 and creates the STOP codon in position 39, which leads to premature termination of translation and significant truncation of the protein. This mutation was described for the first time in the Ashkenazi Jews as founder mutation65,66 and now it is present in 1–16% of the patients with a family history of breast or ovarium cancer, depending on the region of the Polish population55. This aggressive mutation was not detected in any of our studied samples., nor was the second polymorphism studied - rs276174813 of BRCA2. The population frequency of the analyzed mutations is very low, as indicated by the data presented in Table 2, that is probably why no positive case could be found in the study group. Doraczyńska-Kowalik et al. revealed in the Polish population of patients with breast or ovarian cancer, approximately 0.69% had the tested mutations (rs276174813 and rs80357914)67. There are no data regarding the involvement of these polymorphisms in pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis. However, other adjacent polymorphisms were detected based on the changed HRM-PCR curve in the samples (Table S2). In BRCA1, three polymorphisms were detected, in BRCA2—four polymorphisms. They have uncleared clinical significance, but it is worth emphasizing that they were present only in patients, mostly with acute pancreatitis. It is worth examining this on a larger group of patients. Perhaps screening in this region could be used to determine the risk of patients with pancreatic disease or to select a genetic panel for this purpose.

To sum up our research, the group of patients with pancreatic cancer stands out. The statistically significant three-fold increased risk of pancreatic cancer in the case of rs2066847 carriers (OR 2.77, p = 0.019) is the most significant result of this study. This may suggest that NOD2 influences the mechanisms of pancreatic carcinogenesis. Literature indicates that NOD2 mutations may lead to immune response dysfunction, which promotes chronic inflammation and neoplastic progression68.

However, we would like to point out some limitations of the work. The lack of correlation of genetic determinants with pancreatitis may be due to many other etiological factors. Population studies on large numbers of highly homogeneous groups and experimental studies examining the biochemical pathways of the studied polymorphism may be the key to solving this issue. We would like to underline that the prevalence of rs2066847 was higher in patients with chronic pancreatitis (CP) compared with acute pancreatitis (AP). These differences were not statistically significant, but the small size of the CP group may have contributed to the lack of significance, emphasizing the need for larger cohort studies. In the literature, polymorphisms in the NOD2 gene have been associated with various inflammatory conditions, including Crohn’s disease, suggesting a potential molecular mechanism related to the regulation of the immune response and susceptibility to chronic inflammation in the pancreas69. It is worth adding that the literature on the research topic is poor and most of the articles are of an experimental nature, the limited literature on this topic determines the lack of a full discussion of the obtained results. Nevertheless, our results indicate a stronger link between pancreatic cancer and a genetic basis than in other cases examined. As already mentioned at the beginning of this work—pancreatic cancer is one of the most devastating diseases with extremely high mortality associated with late diagnosis, limitations of surgical treatment, and resistance to systemic therapy6,70. It is one of the worst prognosis cancers with a 5-year survival rate of 5–8%. According to the National Cancer Registry, in 2021, in Poland, pancreatic cancer cases accounted for 2.2% of cancers in men and 2.2% of cancers in women, while deaths accounted for 4.6% and 5.5% of all cancer-related deaths, respectively. Current statistics from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 confirm initial predictions, with an estimated incidence of + 0.6% in 2004–2019. As the incidence increased, the mortality rate also increased, although at a slower rate of + 0.3% per year71. Healthcare expenditures showed a positive correlation with morbidity and an inverse correlation with mortality, which was especially true for expenditures on medical care and hospital care. Pancreatic cancer is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States in the next decade. While advances in the treatment of other types of cancer have increased lifespan, mortality from pancreatic cancer has not changed significantly72. Most patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage of the disease and are treated mainly with chemotherapy regimens such as Fofirinox and gemcitabine with nab-paclitaxel73. The overall survival for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer is less than one year. Significant progress in oncological treatment was made after the introduction of molecularly targeted drugs. This is related to modern diagnostics of changes in the genome of cancer cells6,7. Detection of various genetic disorders in pancreatic cancer cells may become a diagnostic and therapeutic goal6,7,8. Gene mutations detected in pancreatic cancer cells are germline and somatic mutations. The influence of hereditary pancreatic cancer susceptibility genes is enhanced by environmental factors such as smoking or alcohol consumption, which favors the formation of pathogenic somatic mutations leading to the development of cancer14.

Conclusions

Single nucleotide polymorphism rs2066847 in NOD2 occurs more frequently in pancreatic patients and may predispose to cancer development, it increases the risk of cancer threefold. There was no correlation of NOD2 variant with acute pancreatitis and chronic pancreatitis. We did not find significant mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, however, the studied regions may be a potential target for further analysis in pancreatic patients.

Materials and methods

Study group

The study included 553 patients with a history of pancreatitis, 83 patients with pancreatic cancer, 44 patients with other pancreatic diseases (e.g. pancreatic cysts, pancreatic tumors, ampullary carcinoma), and 116 healthy volunteers (control group) recruited in the Świętokrzyskie voivodeship from 2013 to 2024. The whole peripheral blood was obtained from the healthy volunteers and patients of Provincial Hospital in Kielce, Holy Cross Cancer Center, and St Alexander Hospital in Kielce, then stored at − 80 °C in the Department of Interventional Medicine with the Laboratory of Medical Genetics, Collegium Medicum of The Jan Kochanowski University in Kielce, Poland. The characteristics of the study group with the inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 5. The study group size was determined based on the average incidence rates of the respective diseases. Specifically, an incidence rate of 35 cases per 100,000 individuals was utilized for acute pancreatitis, while for pancreatic cancer, the corresponding rate was established at 4.9 cases per 100,000 individuals, ensuring an evidence-based and statistically robust approach28,29,30. The participants in the control group were not younger than 56 years old, so age is not a differentiating factor between groups and minimizes the impact of young age on reducing the risk of developing a given disease. The remaining study groups were not differentiated by age, because we wanted to verify every case of the disease, regardless of age, in relation to the genetic factor. The etiology of acute (AP, n = 532) and chronic pancreatitis (CP, n = 21) was divided into seven categories: idiopathic, biliary, alcoholic, postpartum, hyperlipidemia, drug-related, cancer-related, autoimmunological. However, due to the small number of cases with chronic pancreatitis, the etiological agent was reported only in supplements (Table S1). In 92 cases of pancreatitis, the etiological factor could not be determined based on the interview and was classified as ND (not diagnosed). The pancreatic cancer stage TNM was classified according to the American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition. The tumor grade and type of the cancer were classified based on histological examination (64, 65). Detailed clinical data of patients including the type and etiology of disease, family history, sex, and age of patients are presented in Table S1. Data collected in the family history concerned the incidence of pancreatic diseases in general (diabetes, pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer). The data were categorized according to the level of relationship and coded according to the following scheme: no diseases in the family, illness in the mother or father, sick siblings, grandfather or grandmother’s illness, a sick son or daughter, extended family.

DNA isolation and quality control

DNA isolation was performed using a commercial column kit Genomic Micro AX Blood Gravity (A&A Biotechnology, Gdańsk) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Before DNA isolation, the blood was thawed, and the tubes were mixed to homogenize the input material. The material was stored at 4 °C. The quality and quantity of isolated DNA were spectrophotometrically analyzed using a droplet measurement device (DeNovix Ds-11, DeNovix Inc., Wilmington, USA). Absorbance was checked for wavelengths of 230 nm, 260 nm, and 280 nm. The minimum DNA concentration required for the research was 10 ng/µl. Samples for which the above criteria were not met were re-isolated.

PCRs

NOD2

For genotyping NOD2 (NM_001370466.1): c.2938dup (rs2066847) mutations TaqMan SNP Genotyping assays (ThermoFischer Scientifics) were used. The amplification and detection procedure were carried out in total reaction volume 10 µl, containing 5 µl TaqPathTM ProAmpTM Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 0.25 µl TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assay (20×) (ThermoFischer Scientifics), 1 µl Genomic DNA (10ng) and 3.75 µ Nuclease-Free Water (ThermoFischer Scientifics). The PCR amplification was conducted using Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen) with an initial step of 95 °C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s. Random positive samples were sequenced and compared to reference sequence.

BRCA1 and BRCA2

BRCA1 (NM_007294.4): c.68_69delAG (rs80357914) in exon 2 and BRCA2 (NM_ 000059.4): c. 1796_1800del (rs276174813) in exon 10 to reference GRCh38 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq/) were genotyped by PCR amplification and high resolution melting (HRM) curve analysis using specific primers (Table 6) and Master Mix with DNA binding Dye (RT HS-PCR Mix EvaGreen®, A&ABiotechnology, Poland). The following sequences of the primers were kindly provided by the Department of Molecular Diagnostics, Holy Cross Cancer Center, Kielce, Poland.

All primers (synthesized by the oligo.pl company) were designed in this study using BLAST software (The National Center for Biotechnology Information—NCBI) and verified by OligoAnalyzer™ Tool (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc.). The sequences of the primers, the size of PCR products, and the gene regions with accession numbers are presented in Table 6.

The final volume of PCR reagents for each sample was as follows: 5 µL of EvaGreen MasterMix, 1 µL of each 10 pmol primer (Forward and Reverse), 1 µL (10 ng) of DNA or water in negative control, all filled up with water to 10 µL of total volume. The analysis was conducted in a RotorGene Q 5-plex Thermalcycler (Qiagen, Germany) according to the protocol: Initial denaturation 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 67 °C for 30 s (with touchdown 1 °C/10 cycles), 72 °C for 20 s. The fluorescent data were acquired at the end of each extension step during PCR cycles (Excitation on 460 ± 10 nm, detection on 510 ± 5 nm). The HRM analysis was preceded by incubation at 95 °C for 10 s and 40 °C for 20 s (heteroduplex formation). The melting analysis was conducted on the temperature range 73–81 °C. The Rotor-Gene Q proprietary software (version 2.3.5) was used to genotype the different genotypes. The negative derivative of fluorescence (F) over temperature (T) (dF/dT) curve primarily displays the temperature of melting (Tm), the normalized raw curve depicting the decreasing fluorescence versus increasing temperature, and difference curves were used. A sample without genetic variants was used as a negative reaction control. The above testing protocol was optimized and validated using DNA samples with BRCA1 (NM_007294.4): c.68_69delAG (rs80357914) in exon 2 or BRCA2 (NM_ 000059.4): c. 1796_1800del (rs276174813), which were derived from in-house sources. All samples with suspected genetic variants (a different HRM normalization graph and melt curve analysis from the negative reaction control) were verified using reference capillary sequencing using the SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer sequencer (Applied Biosystems by ThermoFisher Scientific). The sequences of the PCR products were compared to the reference sequences of BRCA1 or BRCA2 available from GeneBank using the BLAST platform (Table 6).

Sequencing

Negative samples for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations were randomly sequenced to confirm negative results, as well as all samples suspected of polymorphism. Sequencing of individual samples consisted of four steps: purification of the PCR products, sequencing reaction, purification of the products resulting from the sequencing reaction, and capillary electrophoresis. ThermoFisher Scientific (MA, USA) reagent was used for this procedure. In the first step, PCR products were visually assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis (band intensity), and the samples were diluted twice if necessary. To 5 µL of the sample solution, 2 µL of ExoSap-IT Express PCR Product Cleanup (cat. 75001.200.UL) was added. The samples were mixed and centrifuged (5 s at 1000 × g). The samples were incubated in a Master Cycler X50 (Eppendorf, SE Hamburg, Germany) for 4 min at 37 °C and 1 min at 80 °C and then placed on ice. The individual primers (Table 6) were diluted to 3.2 µM. For each primer, a reaction mixture was prepared consisting 0.5 µL of BigDye Terminator v3.1 Ready Reaction Mix (from BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit, no cat. 4337458), 1 µL of BigDye Terminator v1.1 and v3.1 5× Sequencing Buffer (cat. 4336697), 6.5 µL of deionized water (RNase/DNase-free), 1 µL of primer (3.2 µM), respectively multiplied by the number of samples. The mixture was vortexed and centrifuged (5 s at 1000 × g). Nine microliters of the obtained mixture and 1 µL of the PCR product purified in the previous step were then added to the plate. The plate was sealed, vortexed for 3 s, centrifuged (5 s at 1000 × g), and incubated in a Master Cycler X50 (Eppendorf, SE, Hamburg, Germany) under the following conditions: denaturation at 96 °C for 1 min, followed by amplification for 25 cycles at 96 °C for 10 s, annealing for 5 s at 50 °C, and extension at 60 °C for 4 min, and 4 °C until the samples were ready for purification. A mixture was then prepared per sample: 45 µL of SAM solution (no cat. 4376497), 10 µL of XTerminator solution (cat. 4376493) vortexed, and 55 µL of the solution was added to each well on the plate removed from the thermal cycler to prevent the balls from sinking to the bottom. After resealing with foil, the mixture was vortexed for 20 min at 1800 rpm and centrifuged (2 min at 1000 × g). After changing the foil to septa and checking the buffer level, the plate was inserted into a SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer sequencer (Applied Biosystems by ThermoFisher Scientific) and sequenced on the Short Seq_BDX run module. After the process was completed, the results were automatically saved on the disk in the ab1 format.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative data distributions were described by frequency and percentages. Frequencies were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (in case the sample number is below n = 10). The normality of the distribution was checked with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Due to the violation of the assumption of normality verified by Shapiro–Wilk test (p < 0.05), the distributions of quantitative features were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. All statistical tests were two-sided. The occurrence of specific SNVs between study groups was determined by OR (odds ratio) and RR (relative risk) with confidence interval (95% CI) and it was analyzed statistically using Fisher’s exact or chi-square test, two-sided. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism, version 9 (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for the analyses and derivation of figures.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files (Tables S1 and S2). Anonymized clinical data and detailed genetic results for the study participants are available in Table S1, and HRM-PCR results are available in Table S2. Sequencing chromatograms of PCR products for positive and negative control of BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene fragments as well as HRM-PCR reaction curves is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Le Cosquer, G. et al. Pancreatic cancer in chronic pancreatitis: pathogenesis and diagnostic approach. Cancers 15, 761. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15030761 (2023).

Kirkegård, J. et al. Acute pancreatitis as an early marker of pancreatic cancer and cancer stage, treatment, and prognosis. Cancer Epidemiol. 64, 101647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canep.2019.101647 (2020).

Bassi, C. et al. The 2016 update of the International Study Group (ISGPS) definition and grading of postoperative pancreatic fistula: 11 years after. Surg. (United States). 161 (3), 584–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.11.014 (2017).

Umans, D. S. et al. Pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer: a case of the chicken or the egg. World J. Gastroenterol. 27, 3148–3157. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i23.3148 (2021).

Ebert, M., Schandl, L. & Schmid, R. M. Differentiation of chronic pancreatitis from pancreatic Cancer: recent advances in molecular diagnosis. Dig. Dis. 19, 32–36 (2001).

Ryan, D. P., Hong, T. S. & Bardeesy, N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1039–1049 (2014).

Klein, A. P. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies five new susceptibility loci for pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 9, 556 (2018).

Ansari, D., Torén, W., Zhou, Q., Hu, D. & Andersson, R. Proteomic and genomic profiling of pancreatic cancer. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 35, 333–343 (2019).

Shelton, C. A. & Whitcomb, D. C. Precision medicine for pancreatic diseases. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 36, 428–436 (2020).

Hayashi, A., Hong, J. & Iacobuzio-Donahue, C. A. The pancreatic cancer genome revisited. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 469–481 (2021).

Halbrook, C. J., Lyssiotis, C. A., di Pasca, M. & Maitra, A. Pancreatic cancer: advances and challenges. Cell 186, 1729–1754 (2023).

Guo, K. et al. Exploring the key genetic association between chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma through integrated bioinformatics. Front. Genet. 14, 1115660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2023.1115660 (2023).

Oracz, G. et al. Loss of function TRPV6 variants are associated with chronic pancreatitis in nonalcoholic early-onset Polish and German patients. Pancreatology 21, 1434–1442 (2021).

Zhan, W., Shelton, C. A., Greer, P. J., Brand, R. E. & Whitcomb, D. C. Germline variants and risk for pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 47, 924–936 (2018).

Thompson, E. D. et al. The genetics of ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas in the year 2020: dramatic progress, but far to go. Mod. Pathol. 33, 2544–2563. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0629-6 (2020).

Strum, W. B. & Boland, C. R. Advances in acute and chronic pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 29, 1194–1201. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i7.1194 (2023).

Głuszek, S. & Kozieł, D. Genetic determination of pancreatitis. Med. Stud. 34, 70–77 (2018).

Paniccia, A. et al. Prospective, multi-institutional, real-time next-generation sequencing of pancreatic cyst fluid reveals diverse genomic alterations that improve the clinical management of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology 164, 117–133e7. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2022.09.028 (2023).

Ma, Y. et al. Loss of Heterozygosity for KrasG12D promotes malignant phenotype of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by activating HIF-2α-c-Myc-regulated glutamine metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23126697 (2022).

Lizard-Nacol, S. et al. Loss of Heterozygosity at the TP53 gene: independent occurrence from genetic instability events in node-negative breast Cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 72, 599–603 (1997).

Gu, Y. et al. Impact of clonal TP53 mutations with loss of heterozygosity on adjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 131, 1320–1327. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-024-02825-1 (2024).

Hu, H. et al. Mutations in key driver genes of pancreatic cancer: molecularly targeted therapies and other clinical implications. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 42, 1725–1741. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-020-00584-2 (2021).

Wong, W., Raufi, A. G., Safyan, R. A., Bates, S. E. & Manji, G. A. BRCA mutations in pancreas cancer: spectrum, current management, challenges and future prospects. Cancer Manage. Res. 12, 2731–2742 (2020).

Vittal, A., Saha, D., Samanta, I. & Kasi, A. CHEK2 mutation in a patient with pancreatic adenocarcinoma—a rare case report. AME Case Rep. 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.21037/acr-20-83 (2021).

Nej, K. et al. The NOD23020insC mutation and the risk of familial pancreatic cancer? Hered Cancer Clin. Pract. 2 (3), 149–150 (2004).

Hernandez, D., Wagner, F., Hernandez-Villafuerte, K. & Schlander, M. Economic burden of pancreatic cancer in Europe: a literature review. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 54, 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-022-00821-3 (2023).

Peery, A. F. et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: Update 2021. Gastroenterology 162, 621–644 (2022).

Iannuzzi, J. P. et al. Global incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 162, 122–134 (2022).

Kozieł, D. & Głuszek, S. Epidemiology of acute pancreatitis in Poland – selected problems. Med. Stud. 32, 1–3 (2016).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Shimizu, K. et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for chronic pancreatitis 2021. J. Gastroenterol. 57, 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-022-01911-6 (2022).

Lilly, A. C., Astsaturov, I. & Golemis, E. A. Intrapancreatic fat, pancreatitis, and pancreatic cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 80, 206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-023-04855-z (2023).

Klein, A. P. Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 493–502. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-021-00457-x (2021).

Szatmary, P. et al. Acute pancreatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Drugs 82, 1251–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-022-01766-4 (2022).

Kenner, B. et al. Artificial Intelligence and early detection of pancreatic cancer: 2020 summative review. Pancreas 50, 251–279 (2021).

Kandikattu, H. K., Venkateshaiah, S. U. & Mishra, A. Chronic pancreatitis and the development of pancreatic Cancer. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 20, 1182–1210 (2020).

Zhao, Z. Y. & Liu, W. Pancreatic cancer: a review of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533033820962117 (2020).

Kamimura, K., Yokoo, T. & Terai, S. Gene therapy for pancreatic diseases: current status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3415. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19113415 (2018).

Huang, X., Zhang, G., Tang, T. Y., Gao, X. & Liang, T. B. Personalized pancreatic cancer therapy: from the perspective of mRNA vaccine. Military Med. Res. 9, 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-022-00416-w (2022).

Kolbeinsson, H. M., Chandana, S., Wright, G. P. & Chung, M. Pancreatic cancer: a review of current treatment and novel therapies. J. Invest. Surg. 36, 2129884. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941939.2022.2129884 (2023).

Bhat-Nakshatri, P. et al. Signaling pathway alterations driven by BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations are sufficient to initiate breast tumorigenesis by the PIK3CAH1047R Oncogene. Cancer Res. Commun. 4, 38–54 (2024).

Li, Z. & Shang, D. NOD1 and NOD2: essential monitoring partners in the innate immune system. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 46, 9463–9479 (2024).

Kobayashi, K. S. et al. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science 307, 731–734 (2005).

Kawai, T. & Akira, S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int. Immunol. 21, 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxp017 (2009).

Kim, T. H. et al. Altered host:pathogen interactions conferred by the Blau syndrome mutation of NOD2. Rheumatol. Int. 27, 257–262 (2007).

Sato, H. et al. CARD15/NOD2 polymorphisms are associated with severe pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur. Respir. J. 35, 324–330 (2010).

Kutikhin, A. G. Role of NOD1/CARD4 and NOD2/CARD15 gene polymorphisms in cancer etiology. Hum. Immunol. 72, 955–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humimm.2011.06.003 (2011).

Lener, M. R. et al. Prevalence of the NOD2 3020insC mutation in aggregations of breast and lung cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 95, 141–145 (2006).

Lubiński, J. et al. The 3020insC allele of NOD2 predisposes to cancers of multiple organs. Hered Cancer Clin. Pract. 2, 59–63 (2005).

Branquinho, D., Freire, P. & Sofia, C. NOD2 mutations and colorectal cancer—where do we stand? World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 8 (4), 284–293 (2016).

Liu, J., He, C., Xu, Q., Xing, C. & Yuan, Y. NOD2 polymorphisms associated with cancer risk: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 9 (2), e89340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089340 (2014).

Schnitzler, F. et al. The NOD2 p.Leu1007fsX1008 mutation (rs2066847) is a stronger predictor of the clinical course of Crohns disease than the FOXO3A Intron variant rs12212067. PLoS One. 9 (11), e108503. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0108503 (2014).

Schnitzler, F. et al. Development of a uniform, very aggressive disease phenotype in all homozygous carriers of the NOD2 mutation p.Leu1007fsX1008 with Crohn’s disease and active smoking status resulting in ileal stenosis requiring surgery. PLoS One. 15 (7), e0236421. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236421 (2020).

Antón, M. D. et al. Chronic pancreatitis as the initial presentation of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26, 300–302 (2003).

Hartwig, M. et al. Prevalence of the BRCA1 c.6869delAG (BIC: 185delAG) mutation in women with breast cancer from north-central Poland and a review of the literature on other regions of the country. Wspolczesna Onkologia. 17 (1), 34–37 (2013).

Watanabe, T., Kudo, M. & Strober, W. Immunopathogenesis of pancreatitis. Mucosal Immunol. 10 (2), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2016.101 (2017).

Daly, M. B. et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 19 (1), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.6004/JNCCN.2021.0001 (2021).

Lal, G. et al. Inherited predisposition to pancreatic adenocarcinoma: role of family history and germ-line p16, BRCA1, and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Res. 60 (2), 409–416 (2000).

Salo-Mullen, E. E. et al. Identification of germline genetic mutations in patients with pancreatic cancer. Cancer 121 (24), 4382–4388 (2015).

Lowery, M. A. et al. Prospective evaluation of germline alterations in patients with exocrine pancreatic neoplasms. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 110 (10), djy024. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy024 (2018).

Hu, C. et al. Association between inherited germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc.. 319 (23), 2401–2409 (2018).

Górski, B. et al. A high proportion of founder BRCA1 mutations in polish breast cancer families. Int. J. Cancer. 110, 683–686 (2004).

Ferla, R. et al. Founder mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Ann. Oncol. 18 (Supp. 6), vi93–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm234 (2007).

Werner, H. BRCA1: an endocrine and metabolic regulator. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 844575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.844575 (2022).

Roa, B. B., Boyd, A. A., Volcie, K. & Richards, S. C. Ashkenazi jewish population frequencies for common mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Nat. Genet. 14, 185–187 (1996).

King, M. C. et al. Breast and ovarian Cancer risks due to inherited mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science 302, 643 (2003).

Doraczynska-Kowalik, A. et al. Detection of BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants in patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer and their families. Analysis of 3,458 cases from Lower Silesia (Poland) according to the diagnostic algorithm of the National Cancer Control Programme. Front. Genet. 13, 941375. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.941375 (2022).

Negroni, A., Pierdomenico, M., Cucchiara, S. & Stronati, L. NOD2 and inflammation: current insights. J. Inflamm. Res. 11, 49–60. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S137606 (2018).

Ogura, Y. et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 411, 603–606 (2001).

Takaori, K. et al. International Association of Pancreatology (IAP)/European Pancreatic Club (EPC) consensus review of guidelines for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology 16, 14–27 (2016).

Cucchetti, A. et al. European’ health care indicators and pancreatic cancer incidence and mortality: a mediation analysis of Eurostat data and global burden of Disease Study 2019. Pancreatology 23, 829–835 (2023).

Okano, K. & Suzuki, Y. Strategies for early detection of resectable pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 20 (32), 11230–11240 (2014).

Altimari, M., Wells, A., Abad, J. & Chawla, A. The differential effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation on nodal downstaging in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology 23, 805–810 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by project number SUPS.RN.24.015 financed by Jan Kochanowski University, Kielce, Poland. We would like to thank all swab donors and hospital directors who agreed to this scientific collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.: conceptualization, data curation, resources; W.A.-B.: data curation, statistical analysis of results, tables and figures preparation, writing—original draft, editing, review; M.W.-K.: data curation, methodology, validation, supervision, resources, writing—review, editing; B.M.: data curation, validation, supervision, resources; M.K.: data curation, validation, resources; R.O.: methodology, laboratory work, validation; Ł.M.: methodology, laboratory work, validation; D.K.: data curation, validation, supervision, resources; S.G.: conceptualization, supervision, resources, writing—review and editing.All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author has made substantial contributions to the conception and approved the submitted version. Each author has agreed to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and declares that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and informed consent

The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Collegium Medicum, Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce, Resolution No 1/2012 from 11.04.2012. All participants were informed of the purpose of the project and planned research. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the project. Table S1 presents the anonymized project members with detailed characteristics.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matykiewicz, J., Adamus-Białek, W., Wawszczak-Kasza, M. et al. The known genetic variants of BRCA1, BRCA2 and NOD2 in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer risk assessment. Sci Rep 15, 1791 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86249-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86249-8