Abstract

To promote the recycling of waste glass and satisfy the demands of environmental sustainability for ultrahigh performance concrete (UHPC), in this study, glass sand was employed to partially or entirely replace machine-made sand, and steel fibres were incorporated to fabricate ultrahigh performance shotcrete (UHPS). The effects of glass sand and steel fibres on the mechanical and electrical properties of composite materials were analysed in this study. Furthermore, alkali‒silica reaction (ASR) tests and microstructural analyses were conducted. The results indicate that at higher steel fibre contents, the incorporation of glass sand does not reduce the compressive strength of the UHPS and that glass sand has no significant effect on the split tensile or flexural strength. When the steel fibre content is 2% and the replacement ratio of glass sand reaches 100%, the mechanical properties of the UHPS reach their maximum. The addition of glass sand negatively affects the electrical properties, whereas the use of steel fibres improves them. The results of the alkali‒silica reaction tests confirm that the use of glass sand does not induce harmful expansion reactions. The study revealed the trends in the mechanical and electrical properties of concrete from a microstructural perspective and provided explanations for the alkali‒silica reaction outcomes. This study provides technical support for the application of UHPS to tunnel linings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tunnels are an important part of transportation infrastructure, and the lining structure plays a crucial role in supporting tunnel construction. Shotcrete is concrete mixed with cementitious materials and aggregates; at a specific ratio, shotcrete can be sprayed onto a sprayed surface via a pressure gun and instantaneously compacted. Shotcrete has been widely used in tunnel linings, structural repairs, and steel structure protection layers owing to its advantages, such as shorter final setting time, rapid hydration and hardening speed, higher early-age strength, flexible construction, convenience, and high efficiency1,2,3,4. A composite lining, which is a composite primary lining–waterproof layer–secondary lining structure is usually employed in tunnel construction5. The primary lining is a shotcrete and bolt support that serves as the main load-bearing structure, and the secondary lining is used as the safety reserve. However, ensuring perfect adhesion between the primary lining and the secondary lining is difficult; when these two do not cooperate, the force conditions of the lining change, thereby weakening the supporting function of the composite lining on the surrounding rock6. Moreover, the strength grade of shotcrete used for the primary lining is mostly C30 (compressive strength of 30 MPa), which faces surrounding rock with poor geological conditions, increasing the spray thickness is often necessary to meet the stiffness of the initial support, which increases the bending stress, brittleness, and construction costs7. In tunnel construction, lining structures with greater cost-effectiveness and applicability are urgently needed. Therefore, research on the construction technology of single-layer tunnel linings has been carried out. A single-layer tunnel lining is defined as “A supporting system composed of single or multiple layers of concrete, where the supporting layer and the lining layer are integrated, and the shear force can be fully transmitted between each layer”8. A single-layer tunnel lining with shotcrete is advantageous for decreasing the tunnel excavation volume, saving construction materials, and is used for tunnel construction9.

Ultrahigh performance concrete (UHPC) is a relatively new composite material that offers ultrahigh strength, high toughness and superior durability due to the use of large quantities of highly reactive cements, micron- and nanosized mineral admixtures, very low water‒cement ratios, and optimized particle gradation to produce a maximum packing density10,11. Applying UHPC in tunnel linings can improve many deficiencies of ordinary shotcrete and has become an excellent choice for single-layer permanent linings of tunnels. Currently, few studies address the application of UHPC in shotcrete. Zhang et al.12 combined reactive powder concrete with shotcrete to prepare ultrahigh-performance shotcrete (UHPS). In addition, owing to the high brittleness of plain concrete, the use of plain concrete as a supporting system in soft surrounding rock areas is prone to brittle failure13, and the application of fibres in UHPC significantly improves its strength and toughness. Steel fibres are among the most widely studied fibre materials, mainly due to their high elastic modulus and tensile strength, particularly, copper-coated steel fibres and stainless-steel fibres, with their superior corrosion resistance, exhibit greater durability14. Using steel fibres dramatically improves the lining structure strength and crack resistance15, which is more conducive to the coordinated deformation of both the surrounding rock and the lining and improves the structural integrity. Abbas et al.16 investigated how different steel fibres aspect ratios and volume fractions affect the fluidity and mechanical properties of UHPC and reported that as the steel fibres content increases, the fluidity decreases, and the compressive strength and bending toughness significantly increase. Steel fibres application in UHPC has been comprehensively analysed, but very few studies have been conducted on the UHPS. According to Zhang et al.12, different construction processes have different effects on the compressive strength of steel fibres-containing UHPC. Therefore, further exploration of how steel fibres affect the mechanical properties of UHPS is important.

In UHPC, quartz sand (QS) and river sand (RS) are usually used as high-quality aggregates. Although quartz sand has the advantages of a hard texture, wear resistance, and stable chemical properties, the mining process is time-consuming, generates noise pollution, and has extremely high costs. Moreover, dust pollution will be generated during the crushing process, and workers inhaling dust floating in the air for a long period will cause serious damage to the respiratory system. Excessive use of river sand, as a nonrenewable resource, has resulted in a serious reduction in domestic storage, and the rate of sand mining in many areas has far exceeded the rate of sand replenishment, which will seriously affect the river ecological environment. In recent years, an increasing number of researchers have attempted to use machine-made sand (MS) as a fine aggregate to produce UHPC17. Although machine-made sand is easily accessible, it is obtained by mining various rocks, causing direct damage to the mountain structure and affecting the ecological balance. Considering these adverse effects, UHPC must meet the environmental sustainability requirements. Moreover, a major global problem is waste disposal18. With the development of the glass industry market, the demand for glass is increasing, and the amount of waste glass generated is also increasing. According to statistics from the China National Resources Recycling Association, the output of waste glass reached 24.327 million tons in 2022 (flat glass accounted for approximately 47%), while the recovery rate was only 34.9%. A large amount of waste glass cannot be recycled and is usually discarded in landfills. Because it is not biodegradable, waste glass causes serious environmental pollution, especially in developing countries such as China. Therefore, the application of glass aggregates in concrete has become a highly promising method that can significantly improve the recovery rate of waste materials19. Some researchers have analysed the feasibility of replacing aggregates with glass sand within UHPC. Jiao Yubo et al.20 used waste glass sand to replace quartz sand and river sand within UHPC and obtained the best mechanical properties at a substitution rate of 75%. Nancy A et al.21 adopted glass sand to replace quartz sand within UHPC and proved that glass sand whose average particle size was 275 μm was the best gradation to replace quartz sand. However, no studies have been published on the replacement of machine-made sand with glass sand in UHPC, let al.one its application in UHPS. Consequently, relevant investigations on the application of waste glass sand in UHPS are needed.

According to the above studies, waste glass is applicable in concrete, but glass aggregates have extremely high amorphous silica contents and high alkali reactivities in concrete22,23. The alkali‒silica reaction (ASR) that occurs causes excessive expansion of concrete, presenting potential hazardous risks. Therefore, conducting ASR determination is necessary to verify the feasibility of applying glass aggregates in concrete.

With the rapid advancement of modern transportation networks, tunnels are evolving in the direction of “longer, wider, and deeper” development, and people are increasingly emphasizing the safety of tunnels. When a tunnel accident occurs, it is mostly a malignant accident. Consequently, to ensure tunnel safety during construction and service, tunnel health detection is particularly important. Currently, fibre optic sensors are usually used for structural health monitoring of tunnel linings24,25,26, but they have several limitations, such as strong installation professionalism, high cost, poor durability, and vulnerability to external magnetic field interference27. To overcome these drawbacks, since the 1990s, self-sensing concrete materials have emerged as a potential solution28, among which self-sensing UHPC emerged in 201429. Many researchers have analysed how steel fibres affect UHPC piezoresistivity30,31,32, all of which have yielded good results. However, some researchers have also indicated that UHPC containing steel fibres does not possess piezoresistivity33,34. Zhang et al.12 also reported that incorporating steel fibres alone into a UHPS does not result in good piezoresistivity. Carbon fibres, as widely used conductive materials, achieve good self-sensing performance when applied to concrete. Wang35 and Zhang et al.36 successfully developed high-performance shotcrete (HPS) and UHPS with excellent sensing performance using carbon fibres, but both have the disadvantage of poor toughness in mechanics. If steel fibres and carbon fibres are used in combination, they may compensate for the poor toughness of the UHPS while having good self-sensing ability. However, studies have not been conducted on UHPS, which highlights the importance of relevant research.

In this study, waste glass sand and steel fibres were used as the main variables. The application of glass sand in UHPS was explored, with the aim of partially or completely replacing machine-made sand with glass sand to produce UHPS. Applying such a process improves the utilization rate of waste glass sand, reduces environmental pollution, and meets the sustainable development needs of UHPC. In addition, based on Wang et al.35 in our research group, a certain content of carbon fibres was used, and different contents of steel fibres were added to improve toughness while providing self-monitoring ability for the UHPS. The effects of the glass sand substitution rate and different steel fibres contents on the mechanical performance (compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths) and self-sensing properties (piezoelectricity and bending sensitivity) were analysed, and the effect of glass sand replacement was evaluated through ASR. The UHPS microstructure was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

Materials and methods

Raw materials

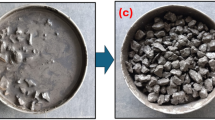

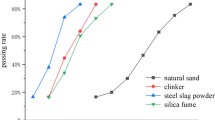

The cementitious material used in the test is P.II52.5 cement, which meets the requirements of “General Portland Cement” (GB175-2020)37. Silica fume is produced and tested by Gansu Sanyuan Silicon Materials Co., Ltd., and fly ash is produced and tested by Hebei Shengyi Mining. Metakaolin is produced and tested by Inner Mongolia Chaopai New Materials Co., Ltd., all of which meet the requirements of “Technical Specification for the Application of Mineral Admixtures” (GB/T 51003-2014)38. All the aggregates used in the test are machine-made sand and glass sand. The gradation curve showing machine-made sand can be observed in Fig. 1, and the raw material of glass sand is waste flat glass, as shown in Fig. 2. The chemical composition and physical characteristics of the cementitious materials and aggregates are detailed in Table 1. The fibres used in the test are as follows: the carbon fibres used are Taili short-cut carbon fibres (TC-35), and the steel fibres used are copper-plated steel fibres produced by Shandong Hongjude Metal Co., Ltd. Table 2 displays the fibre specifications and physical characteristics. The water reducing agent adopted during the concrete mixing process is a polycarboxylic acid-based high-performance water reducing agent, which achieves a reduction rate of 47%. The appearances of the glass sand, machine-made sand, steel fibres, and carbon fibres are shown in Fig. 3.

Mix design

The proportion of cementitious materials used in this test was cement: silica fume: fly ash: metakaolin = 0.7: 0.1: 0.1: 0.1. The water-binder ratio (w/b), sand-binder ratio, and contents of the carbon fibres and water reducing agent are 0.2, 0.7, 0.7% and 0.8%, respectively. A total of 25 groups with mix designs were designed in this test, as shown in Table 3.

Specimen preparation

To prevent the carbon fibres from agglomerating, the cementitious materials and aggregates are placed in the mixer and stirred for 2 min, the carbon fibres are added, and the mixture is stirred again for 2 min to fully disperse the carbon fibres. Next, the water reducing agent and water are blended in advance and introduced into the mixer and stirred for 2 min. Then, the steel fibres are screened into the mixer via a sieve with a 16 mm mesh during the operation of the mixer, and the stirring is continued for 1 min. After the slurry is stirred, it is quickly transferred to the hopper of the sprayer, and the machine is turned on for spraying. The spray nozzle is oriented at 90° to the large plate, and the large plate is oriented at 45° to the ground. The samples are sprayed from the bottom up. The spraying process and the effect of single-point spraying are shown in Fig. 4, and the thickness of single-point spraying is 140 mm.

After they are sprayed, to simulate the maintenance conditions in the tunnel, the samples were subjected to outdoor curing for 24 h and then demoulded and naturally maintained until the required age was reached. The large plate samples are cut into the required test samples via a rock cutting machine.

Test method

Fluidity

According to the provisions of the “Method for Determination of Cementitious Sand Fluidity” (GB/T2419-2005)39, the fluidity of the mixture was determined, and the test process is shown in Fig. 5. The table jumping experiment revealed that the mixes with flowability between 140 mm and 160 mm had the best bonding effect to the large plate and achieved better performance. When the flowability was less than 140 mm, the nozzles were clogged, and spraying could not be carried out. When the flowability was greater than 160 mm, the thickness of the single-point spray was reduced.

Compacted packing density

To obtain the most compacted packing density of glass sand, first, the glass sand is screened into three zones, Zone I: 0.15–0.3 mm (fine sand); Zone II: 0.3–0.6 mm (medium sand); Zone III: 0.6–1.18 mm (coarse sand). Second, according to the provisions of 6.5 in the “Standard for Quality and Inspection of Sand and Stone for Ordinary Concrete” (JGJ52–2006)40, the stacking ratio of Zones I and II in terms of the most compacted packing density is obtained, and then Zones I and II are regarded as a new whole and mixed with Zone III to obtain the optimal gradation of the entire system in the most compacted packing density. Figure 6 displays the test procedure.

Mechanical properties

Based on the provisions of the “Standard for Test Methods of Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete” (GB/T50081-2019)41, sample mechanical properties, including compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths, are tested. In the compressive strength test, the sample size and loading rate were 100 × 100 × 100 mm and 1 MPa/s, respectively; in the splitting tensile strength test, the sample size and loading rate were 100 × 100 × 100 mm and 0.1 MPa/s, respectively; and in the flexural strength test, the sample size and loading rate were 100 × 100 × 400 mm and 0.1 MPa/s, respectively. Three samples are obtained for each group of tests. Figure 7 displays the test procedure.

Electrical properties

For the electrical test, the dual-electrode arrangement method was adopted, and the electrode used a steel mesh. The electrode device is shown in Fig. 8a. Since the sample is obtained by cutting a large plate, the electrode is embedded in the concrete, and the electrode needs to be exposed before the test and then connected to an external DC power supply with a voltage of 1 V. To eliminate how the polarization effect affects our test results, the test sample needs to be preelectrified before the test, and the formal test can be performed until the current stabilizes.

In the piezoelectricity test, the sample size was 100 × 100 × 300 mm, and the detailed test device is shown in Fig. 8b. The loading method was cyclic loading at 1 kN/s. To prevent the sample from shifting at the no-load moment and affect the test results, the lower load limit is set to 1 kN, and the current value at this moment is recorded as the initial value.

In the flexural-sensitive test, the sample size is 100 × 100 × 400 mm, and the detailed test device is shown in Fig. 8c. The four-point bending loading method is adopted, and the loading rate is monotonic loading at 0.1 mm/min.

The results of the electrical performance test are expressed as the resistivity change rate (FCR), and its calculation formula is as follows:

where ρ is the resistivity, Ω·mm; ρi is the resistivity at any given time; ρ0 is the resistivity at the initial time; R represents resistance, Ω; U indicates voltage, V; S represents the sample cross-sectional area, mm2; and L represents electrode spacing, mm.

Alkali-silica reaction

According to the provisions of 3.38 in the “Test Code for Hydraulic Concrete” (SL/T352-2020)42, the ASR is determined via the rapid mortar bar method, and the test device and process are shown in Fig. 9. First, a 25.4 × 25.4 × 285 mm steel mould is used, the concrete is filled into it and fully vibrated, put into the standard curing room, demoulded following 24 h of curing, and the initial length is determined. Second, the samples are immersed in a curing bucket filled with tap water and cured in an 80 °C water bath for 24 h, and the reference length is measured. Third, they are immersed in a curing bucket filled with 1 mol/L NaOH solution and put into an 80 °C water bath for curing. Last, the sample length under various curing ages is determined. The expansion rate formula of the sample is as follows:

where εt represents the sample expansion rate after t days; Lt represents the sample length after t days, mm; L0 represents the sample reference length, mm; Δ represents the probe length, mm; Lp represents the reading of the micrometer after the sample is tested, mm; Ls represents the reading of the micrometer after the standard rod is tested, mm; and P represents the length of the standard rod, with a value of 300 mm.

Results and discussion

Optimization of glass sand gradation via compacted packing density

By using the compacted packing density test method, the binary combination packing density between the two finer glass sands in regions I and II was determined, and the results are shown in Fig. 10a. Generally, the binary mixture has a higher packing density than the single-component packing density. The packing density clearly increases and then decreases as the mixing ratio increases. During the continuous increase in the mixing ratio, the finer glass sand fills the voids between the coarser glass sands, decreasing the compactness of the voids in the system. When the finer glass sand completely fills the voids and there is no remainder, the packing density at this point is the highest. With a further increase in the mixing ratio, excessive finer glass sand will reduce the packing density. When the ratio of fine sand to medium sand is 0.35, the binary combination results in the best packing density of 1346.5 kg/m3. After the optimal ratio of fine sand to medium sand is obtained, it is regarded as a whole, and in the same way, the bulk density of mixing with coarse sand is determined, and the results are shown in Fig. 10b. When the ratio of fine sand to medium sand to coarse sand is 0.111:0.317:0.571, the ternary combination results in the best packing density of 1433.3 kg/m3. Figure 11 shows the gradation curve of the glass sand. The gradation of glass sand after optimization is very similar to that of machine-made sand, and it can be effectively used to replace machine-made sand.

Mechanical properties

This section systematically analyses how waste glass sand and steel fibres affect the mechanical performance of concrete, including the compressive strength at 1 d, 3 d, 7 d, 14 d, and 28 d, the splitting tensile strength at 28 d, and the flexural strength.

Compressive strength

Table 4 shows the compressive strength experimental results for the UHPS with different glass sand and steel fibre contents under natural curing conditions at different ages. The compressive strength clearly increases as the curing time increases, but the growth rate changes. Figure 12 shows the relationship between the curing time interval and the average growth rate of the compressive strength. The growth rate of the compressive strength clearly decreases as the curing age increases, which is consistent with the experimental results of Masoud Pourbaba et al.43. This is because the cement utilized is 525 Portland cement, which has a faster hydration rate in the early stage, generating a large amount of C-S-H gel and Ca(OH)2. The secondary hydration reaction between Ca(OH)2 and pozzolanic materials also proceeds at a faster rate, which benefits from the use of metakaolin. Erhan et al.44 reported that the use of metakaolin accelerated the early strength gain of concrete. Simultaneously, during early concrete hardening, many pores inside the concrete are filled with hydration products, which makes the compressive strength develop faster in the early stage. The rate of increase in compressive strength decreases with increasing age, which is due to the use of fly ash, which separates cement particles or sticks them to cement particles, resulting in the volcanic ash reaction in the region of the fly ash particles not reacting at an early stage, and as the age increases, the fly ash begins to undergo a slow hydration reaction45. Moreover, owing to the low water/cement ratio used, too much unreactable cementitious material acts as a pore-filling material in the later stages, which causes a slow increase in strength in the later stages.

In terms of the 28-day strength, regardless of the change in steel fibre content, the sample compressive strength initially decreases and then increases as the substitution rate of glass sand increases. Although the content of steel fibres does not affect the change trend of the compressive strength with the content of glass sand, the turning point of the change trend of the compressive strength changes with increasing steel fibre content. When the steel fibre content is less than 1% and the substitution rate of glass sand increases from 0 to 75%, the compressive strength decreases, and the maximum compressive strength appears at a substitution rate of 0%. This may be because with the incorporation of glass sand, the gradation of the original machine-made sand is disrupted, and glass sand has more angular shapes than machine-made sand does, which causes concentrated stress at the corners of the matrix when it is subjected to pressure, resulting in an uneven stress distribution. The above comprehensively explains the reduced sample compressive strength. However, at a substitution rate of 100%, the compressive strength slightly increases because the gradation is improved at this point, but its strength is also slightly lower than that at 0% substitution. When the steel fibre content reached or exceeded 1%, the substitution rate of glass sand increased from 0 to 50%, the compressive strength decreased, and the compressive strength no longer reached a maximum at a 0% substitution rate of glass sand but reached a 100% substitution rate. When a sample is subjected to pressure, due to shear slip and the Poisson’s ratio effect, tensile stress is also generated inside the sample. During the deformation process, the steel fibres are gradually removed from the matrix. Compared with machine-made sand, glass sand has an irregular and multiangular shape, which further hinders the pullout process of the steel fibres. As the glass sand content increases, the energy consumed in the pullout process also continues to increase, resulting in increased compressive strength. However, with a lower content of steel fibres, the synergistic effect between the glass sand and the steel fibres cannot be well demonstrated, resulting in the above phenomenon.

The incorporation of steel fibres increases the sample compressive strength, and as the steel fibre content increases, regardless of the change in the glass sand substitution rate, the compressive strength generally tends to increase, which conforms to the research results of Yang Jian et al.46. The mean sample compressive strength without steel fibres is 105 MPa, and when 2% steel fibres are incorporated, the mean sample compressive strength is 130.6 MPa, which is an increase of 24.4%. The reason for this phenomenon is that as the steel fibres increase, the spacing between the steel fibres decreases, more fibres bear the load, more cracks form during the failure process, and the increase in steel fibres delays the formation of cracks and hinders their development, resulting in an increase in strength47.

Splitting tensile strength

Table 5 displays the experimental results for the splitting tensile strength. These results show that regardless of the change in the steel fibre content, the splitting tensile strength of the concrete samples does not change significantly with increasing substitution rate of glass sand, which is in accordance with the experimental results of Nafisa Tamanna et al.48. Corresponding to the five groups of diverse steel fibre contents, the effects of changes in the amount of glass sand on the splitting tensile strength fluctuate at approximately 8, 12, 15, 16, and 19 MPa. The possible reason for the above phenomenon may be that the tensile strength of concrete is much lower than its compressive strength. Therefore, when the concrete matrix containing steel fibres is subjected to tension, although the multiangular appearance of the glass sand can improve the interlocking of the cement and the glass sand, the change in steel fibre content more significantly affects the splitting tensile strength than the impact of the aggregate on the splitting tensile strength20. The same trend is also shown for the concrete matrix without steel fibres because a certain content of carbon fibres is used in this experiment, and its impact on the splitting tensile strength also significantly increases relative to that of the aggregate. Therefore, the result of the insignificant effect of the glass sand substitution rate on the splitting tensile strength is obtained. In addition, adding steel fibres significantly improves the splitting tensile strength. After adding 2% steel fibres, the average splitting tensile strength increased by 137.5% relative to that of the control group. The possible reason for this result is that after adding steel fibres, the fibres are tightly combined with the concrete matrix to resist tensile stress. As the steel fibre content increases, the fibres become tighter. When the matrix cracks, the fibres bridge the cracks. Concurrently, increasing the steel fibre content increases the matrix‒fibre contact area, which is more conducive to the conduction of stress and efficiently hinders crack development, thereby improving the splitting tensile strength49.

Flexural strength

Table 6 displays the experimental results for flexural strength. The same conclusion is obtained for the splitting tensile strength. Regardless of the content of steel fibres, glass sand does not significantly influence the flexural strength of the samples, which conforms to the experimental conclusions of Nafisa Tamanna et al.48. For the five groups with different steel fibre contents, the effects of changes in the amount of glass sand on the flexural strength fluctuate at approximately 6, 12, 15, 19, and 21 MPa. The possible reason is the same as that of the splitting tensile strength: the ultimate load of the flexural strength is mostly determined by the reinforcing effect of the fibres and that the influence of the substitution rate of the glass sand on the flexural strength is greatly weakened. Moreover, adding steel fibres significantly improves the flexural strength. After 2% steel fibres are added, the average flexural strength increased by 210.7% relative to that of the control group. Simultaneously, the samples without steel fibres exhibit brittle failure when they are damaged, and cracking causes failure, whereas the addition of steel fibres remarkably improves the failure mode, resulting in ductile failure and significantly increasing the toughness. This can be ascribed to a similar reason for the splitting tensile strength. When a sample does not crack, the steel fibres can be closely bound to the matrix. When initial cracking occurs, the steel fibres bridge the cracks. As the steel fibre content increases, the fibre bridging ability increases, causing an increase in the fibre‒matrix bonding area. If the cracks in a sample tend to further develop, it needs to overcome a greater force. Therefore, the flexural strength increases50.

Electrical properties

In this section, the effects of the substitution rate of waste glass sand and the content of steel fibres on the electrical properties of concrete under the condition of a constant carbon fibre content (0.7% CF), including the effects of glass sand and steel fibres on the initial resistivity and piezoelectricity of concrete, are analysed. Combined with the above analysis, considering the weak impact of glass sand on flexural strength, only the impact of steel fibres on it is considered in bending sensitivity tests.

Initial resistivity

Figure 13 shows the effects of the glass sand substitution rate and steel fibre content on the initial resistivity of a sample at a curing age of 28 days and a sample size of 100 × 100 × 300 mm. Both variables clearly have different degrees of impact on the initial resistivity of the samples. When the steel fibre content is constant, the initial resistivity tends to increase as the glass sand substitution rate increases. This is because glass sand, as an amorphous solid, can be a good insulator, and its resistivity is much higher than that of ordinary aggregates. When glass sand is incorporated, electron movement inside the sample matrix is hindered. Therefore, as the glass sand content increases, the initial resistivity of the sample increases, which conforms to the results of Wang et al.35. The steel fibre content also negatively affects the initial resistivity of a sample. As the steel fibre content increases, the initial resistivity of a sample significantly increases. Taking the glass sand content of 100% as an example, the resistivity of the sample containing 0.5% steel fibres increases by 266% relative to that of the sample without steel fibres. The possible reason is that the addition of steel fibres severely affects the distribution of carbon fibres in the matrix, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of conductive paths that originally overlapped, hindering the formation of the tunneling effect and significantly increasing the initial resistivity; as the steel fibre content increases, the initial resistivity stabilizes because at steel fibre contents > 0.5%, the contact points between steel fibres increase significantly51. Concurrently, the probability of the steel fibres and carbon fibres overlapping also increases. These newly generated conductive paths compensate for the negative effects caused by the uneven distribution of carbon fibres. Therefore, the phenomenon whereby the initial resistivity stabilizes occurs.

Piezoresistivity

Figure 14 shows the effects of the glass sand substitution rate and steel fibre content on the sample piezoresistivity at a curing age of 28 days and a sample size of 100 × 100 × 300 mm. In the three-cycle loading, there is a good correspondence between the load and the FCR; in other words, as the load increases and decreases, the FCR also decreases and increases. When the matrix is under pressure, compressive deformation will occur, resulting in changes in the contact between the conductive functional fillers and changes in the intrinsic resistivity. In this study, owing to the effect of the pressure load, the spacing between the fibres decreases, and the intrinsic resistivity of the conductive filler decreases, making electron transmission easier, and more fibres overlap to generate conductive paths, resulting in a decrease in the resistivity of the matrix. Because the concrete is always in the elastic stage under the action of the load, deformation can be recovered during the unloading process; therefore, the resistivity of the matrix increases. Under different substitution rates of glass sand, the FCR shows different magnitudes of change. As the glass sand content increases, the FCR becomes increasingly moderate. This occurred because glass sand has a relatively high resistivity, which hinders electron transfer in the matrix. In addition, in the literature, a higher sand–binder ratio has a more significant effect on the FCR52. Therefore, the glass sand in this experiment had a more significant effect on the FCR.

The horizontal comparison shows that the steel fibres also affect the FCR. As the steel fibre content increases, the FCR becomes steeper and then stabilizes. In this experiment, because of the low water‒binder ratio used in the mixture, the ionic conductivity is weak, so the matrix conductivity mainly depends on electron transfer, and electron transfer depends mainly on the distribution of the conductive fibres. When steel fibres are added, the distribution of carbon fibres is affected, and the initial resistivity increases, but the total amount of fibres increases. When the fibers are subjected to pressure loading, the spacing between them decreases, which is more conducive to electron transfer, and the probability of forming conductive paths between fibres continues to increase, so the FCR becomes steeper. As the steel fibre content continuously increases, although the total fibre number increases, the carbon fibre dispersion in the matrix is significantly affected, resulting in the FCR not being further improved but slightly decreasing and then stabilizing.

A detailed change is also shown in Fig. 14. Although the FCR has good reciprocity under the three-cycle load, an irreversible decrease in resistivity occurs after each cycle. This decrease is slight, possibly because under the action of the pressure load, the initial defects and pores existing in the matrix are compacted, which causes permanent slight deformation, resulting in closer proximity or overlap between more fibres, thereby reducing the resistivity53.

Bending sensitivity

Figure 15 shows the effects of bidirectional conductive admixtures with varying steel fibre contents (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0%) and quantitative carbon fibres (0.7% CF) on the load‒deflection‒FCR curve of the concrete during bending. When no steel fibres are added, the sample clearly experiences brittle failure, and the contribution of using only carbon fibres to the flexural sensitivity is limited. When steel fibres are added, both the ultimate load and the peak deflection tend to increase, and the concrete beams all exhibit flexural hardening behaviour; that is, the ultimate load is greater than the cracking load, and its toughness is significantly greater. In the first cracking process of the concrete beam with steel fibres, the FCR-deflection curve shows a significant linear increase. As the steel fibre content increased, the slopes of the FCR-deflection curves in the first cracking process were 246.5, 65.5, 27.2, and 12, respectively. The trend becomes increasingly moderate, which means that increasing the steel fibre content reduces the cracking sensitivity of the concrete beam, since after adding steel fibres, the crack development in the first cracking process is slower, resulting in a slower change in the FCR. After the first drop in the load, a plateau appears on the FCR-deflection curve, which was also observed by Ding et al.54, and the length of the plateau is continuously shortened as the number of steel fibres increases. As the load increases, the FCR-deflection curve becomes steeper in the rising process, and the steepness of the curve further increases with increasing steel fibres.

According to the provisions of the “Code for Design of Concrete Structures” (GB50010-2010)55, the deflection of a concrete beam with a span of less than 7 m is limited to l0/200 (l0 is the span) in the normal service limit state. In this experiment, the span of the beam used is 400 mm; that is, the allowable maximum deflection is 2 mm. Since the concrete beam without steel fibres has already failed at a deflection of 2 mm, the values of FCR at a deflection of 2 mm with steel fibre contents of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0% are given, which are 55.2, 41.1, 25.5, and 2.2%, respectively, indicating that under the same deflection, the FCR decreases with increasing steel fibres. When there are more steel fibres, there are more fibre-bridged cracks, and the conductive network is more stable during the cracking process54.

A detailed change is shown in the figure. At a low steel fibre content (0, 0.5%), the FCR decreases with increasing load before the concrete beam cracks, as shown in Fig. 15a, b, whereas with increasing steel fibre content, the FCR does not change before cracking, as shown in Fig. 15c–e. When the concrete beam is bent, the upper part of the beam neutral axis is under compressive stress, which makes the upper part of the matrix more compact, resulting in a decrease in resistivity and then a decrease in FCR. As steel fibres increase, the compressive strain generated under the same compressive stress is not enough to cause a change in resistivity, so the FCR does not change. In the later stage of the development of the FCR-deflection curve of the concrete beam containing steel fibres, the noise signal is improved, and this trend becomes more moderate as the steel fibre content increases. At a later stage in the development of cracks in concrete beams, many of the fibres may separate again after having overlapped at some point during the pull-out process27, this phenomenon further increases the probability of occurrence with an increasing number of fibres pulled out. Therefore, the instability of the conductive path occurs in the later stage. As the steel fibre number increases, the rate of crack development in the concrete beam decreases, and although the fibres are constantly being pulled out, the stability of the conductive path is better than that of the low fibre content. Therefore, the noise signal is weakened.

ASR

The application of glass in concrete is limited because the amorphous silica in glass sand reacts with alkaline substances to form ASR gel, which expands when it encounters water, resulting in cracking and damage to the concrete. Therefore, the ASR expansion of glass sand applied in concrete was evaluated. Since the fibres do not undergo an ASR reaction, the effect of the fibres on the ASR is not considered.

Figure 16 shows the variation in the ASR expansion rate with time for samples without steel fibres for different glass sand substitution rates. At 14 days, the sample containing 100% glass sand exhibited the highest expansion, with an expansion rate of 0.061%, which is far lower than the safety standard of 0.1%. Therefore, the glass sand used in this experiment does not have a harmful alkali‒silica reaction. The reasons for this low ASR expansion can be attributed to the following points: (1) When glass sand whose particle size is < 1 mm is used, the ASR gel produced by its reaction with alkaline substances in the concrete will not expand when it encounters water, and this gel will strengthen the cement matrix–glass sand bonding force56. The glass sand used in this experiment has a maximum grain size of 1.18 mm, and the proportion of > 1 mm glass sand is very small. (2) The glass sand used in this experiment has a maximum grain size of 1.18 mm, and the proportion of > 1 mm glass sand is very small. (2) The water-binder ratio used in the test is 0.2, resulting in very high compactness of the concrete. During the rapid mortar bar test, the alkaline solution cannot easily enter the interior of the concrete to react with the glass sand. (3) A certain amount of fly ash and silica fume are used in the mix ratio of this study, and the use of these pozzolanic materials also inhibits the development of ASR57, and the presence of carbon fibres also reduces the expansion rate.

SEM

Aggregate morphology and the ITZ

Figure 17 shows the SEM observations of the concrete samples after the ASR test (with a GS substitution rate of 50%). The aggregate size clearly has a greater effect on the compressive strength. As shown in Fig. 17a, b, there are significant differences in the appearances of glass sand and machine-made sand. The shape of machine-made sand is more regular and mostly prismatic, whereas the shape of glass sand is mostly flat, elongated, and angular, which results in stress concentration at the tip position more easily under pressure. Moreover, adding glass sand disrupts the gradation of machine-made sand, which explains the decreased compressive strength after adding glass sand (0-75%). Figure 17c, d show that the aggregates are tightly bonded to the matrix and that there are no obvious defects in the ITZ. Furthermore, because glass sand has an irregular shape, the bonding surface area with the matrix is larger than that of machine-made sand, while the gradation of aggregates is also improved when 100% GS is used, which explains the increasing compressive strength with the continuously increasing glass sand substitution rate (75-100%).

A close examination in Fig. 17d reveals that the ITZ of the sample is extremely thin and devoid of any discernible flaws. Moreover, no ASR gel or cracks are detected around the glass sand. Additionally, the relatively low ASR expansion can be attributed to the conclusions of Rajabipour et al.58, who reported that ASR occurs within microcracks inside larger glass and that no expansive ASR gel is generated on the glass surface. Figure 17b shows that there are no significant defects within the glass sand used in this study, which also explains the low ASR expansion rate.

Fibre Pullout performance

Figure 18 presents the SEM observations of the concrete samples containing 100% GS and 1% SF. As depicted in Fig. 18a, upon compressive stress, the irregular shape of the glass sand results in a tight mechanical interlocking phenomenon with the steel fibres, which severely hinders the pullout of the steel fibres, which indicates the existence of favourable synergy between the steel fibres and glass sand and explains the change in the turning point of the compressive strength development trend as the steel fibre content increases.

Figure 18b, c show that during the four-point bending test and the splitting tensile test, concrete debris is observed on the steel fibre surface, where numerous dense scratches are observed. Figure 18d shows that, owing to the pullout of steel fibres, a certain number of cracks are generated at the steel fibre-matrix junction. These phenomena indicate that the steel fibres are crucial for the sample splitting tensile strength and bending strength, which explains the small effect of the glass sand on them, whereas the steel fibres play an important role.

Fibre distribution state

Figure 19 shows the SEM observations of the concrete samples with varying steel fibre contents under the condition of a GS substitution rate of 50%. Figure 19a–c show the distributions of carbon fibres with steel fibre contents of 0%, 1%, and 2%, respectively. With no addition of steel fibres, they are clearly uniformly dispersed in the matrix, and the phenomenon of carbon fibre bridging is observed. However, when steel fibres are incorporated, the carbon fibre distribution is affected, and the phenomenon of carbon fibre agglomeration occurs, resulting in a decrease in the conductive path, which is more significant under 2% SF, explaining the increase in the initial resistivity after adding steel fibres. Figures 18d and 19d show that steel fibre and carbon fibre bridging and steel fibre bridging compensate for the decrease in the conductive path caused by the agglomeration of carbon fibres, which explains the stabilization of the initial resistivity with the continuous increase in steel fibres.

Conclusion

In this study, the grading of glass sand was optimized, replacing manufactured sand with glass sand, and the UHPS was prepared by incorporating steel fibres in varying proportions. The following conclusions were drawn:

-

(1)

Under natural curing conditions, there is a good synergistic effect between a higher dosage of steel fibres and glass sand. The use of glass sand to replace the mechanism sand in the UHPS can improve the compressive strength. the effect of glass sand on the splitting tensile strength and flexural strength is not significant, and the addition of steel fibre significantly improves the mechanical properties of UHPS. When the replacement rate of glass sand is 100%, the dosage of steel fibres is 2%, the mechanical properties reaches a maximum, with compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength being 135.16 MPa, 19.49 MPa, and 21.69 MPa, respectively.

-

(2)

The results of the electrical tests showed favourable results. The addition of glass sand significantly increased the initial resistivity and weakened the pressure sensitivity; steel fibres had a positive effect on both the pressure and bending sensitivity but increased the initial resistivity.

-

(3)

The effects of different glass sand contents on the ASR were analysed, and the results revealed that the expansion rates were all within the safety limits, indicating satisfactory results.

-

(4)

SEM observations of the aggregate morphology, interfacial transition zone (ITZ) and bonding of steel fibres to the matrix rationally explain the developmental changes in compressive strength and the reason for the lower expansion of glass aggregates and elucidate the key role of steel fibres in split tensile strength and flexural strength. Moreover, the distribution of fibres in the matrix was analysed to explain the effect of steel fibres on the initial resistivity.

The glass sand produced from recycled and reused waste flat glass not only has excellent environmental protection advantages but also has excellent performance in UHPS applications. While meeting the environmentally sustainable development needs of UHPC, glass sand has great potential as an alternative material for traditional aggregates.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Bryne, L. E., Ansell, A. & Holmgren, J. Investigation of restrained shrinkage cracking in partially fixed shotcrete linings. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 42, 136–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2014.02.011 (2014).

Tong, J. et al. Shear strength characteristics of shotcrete–rock interface for a tunnel driven in high rock temperature environment. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resources. 2, 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40948-016-0039-x (2016).

Wang, J., Niu, D. & He, H. Frost durability and stress–strain relationship of lining shotcrete in cold environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 198, 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.264 (2019).

Cengiz, O. & Turanli, L. Comparative evaluation of steel mesh, steel fibre and high-performance polypropylene fibre reinforced shotcrete in panel test. Cem. Concr. Res. 34(8), 1357–1364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2003.12.024 (2004).

Ye, Z. et al. Application of transient electromagnetic radar in quality evaluation of tunnel composite lining. Constr. Build. Mater. 240, 117958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117958 (2020).

Ding, H. et al. Aseismic performance analysis of composite lining embedded in saturated poroelastic half space. Int. J. Geomech. 20(9), 04020156. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0001787 (2020).

Yang, F., Sun, C. & Qiu, P. Research on the application of high strength shotcrete in railway tunnels. Railway Eng. 10, 111–113. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-1995.2015.10.23 (2015).

Guan, B. Tunnel engineering design key points. Beijing:People’s Traffic Press. 394–397, 419–420 (2003).

Li, Z. et al. Performance of single-layer lining using shotcrete and reinforcement ribs employed for supporting large-span tunnel. Materials 16(24), 7590. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16247590 (2023).

Zhou, M. et al. Mixture design methods for ultra-high-performance concrete-a review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 124, 104242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104242 (2021).

Abbas, S., Nehdi, M. & Saleem, M. Ultra-high performance concrete: mechanical performance, durability, sustainability and implementation challenges. Int. J. Concrete Struct. Mater. 10, 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40069-016-0157-4 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Preparation, mechanics and self-sensing performance of sprayed reactive powder concrete. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 7787. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11836-y (2022).

Xu, G. et al. Progressive failure process of secondary lining of a tunnel under creep effect of surrounding rock. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 90, 76–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2019.04.024 (2019).

Khan, M., Abbas, Y. & Fares, G. Review of high and ultrahigh performance cementitious composites incorporating various combinations of fibers and ultrafines. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 29(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksues.2017.03.006 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Comparison of the structural behavior of reinforced concrete tunnel segments with steel fiber and synthetic fiber addition. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 103, 103506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2020.103506 (2020).

Abbas, S., Soliman, A. M. & Nehdi, M. L. Exploring mechanical and durability properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating various steel fiber lengths and dosages. Constr. Build. Mater. 75, 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.11.017 (2015).

Ma, R. et al. Feasibility study on preparing economical and environmentally-friendly high-flowability ultra-high performance cementitious composites with original graded stone powder free recycled manufactured sands. J. Clean. Prod. 390, 136190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136190 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. RETRACTED: influence of eco-friendly fine aggregate on macroscopic properties, microstructure and durability of ultra-high performance concrete: a review. J. Building Eng. 65, 105783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105783 (2023).

Gholampour, A. et al. Concrete containing recycled concrete coarse aggregate and crushed glass sand: mitigating the effect of alkali–silica reaction. Struct. Concrete. 25, 3682–3702. https://doi.org/10.1002/suco.202301029 (2024).

Jiao, Y. et al. Mechanical and fracture properties of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing waste glass sand as partial replacement material. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 123501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123501 (2020).

Soliman, N. A. & Tagnit-Hamou, A. Using glass sand as an alternative for quartz sand in UHPC. Constr. Build. Mater. 145, 243–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.03.187 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. Experimental and numerical study of long-term alkali-silica reaction (ASR) expansion in mortar with recycled glass. Cem. Concr. Compos. 139, 105043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105043 (2023).

Dong, W., Li, W. & Tao, Z. A comprehensive review on performance of cementitious and geopolymeric concretes with recycled waste glass as powder, sand or cullet. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 172, 105664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105664 (2021).

Gómez, J., Casas, J. R. & Villalba, S. Structural Health Monitoring with distributed optical Fiber sensors of tunnel lining affected by nearby construction activity. Autom. Constr. 117, 103261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103261 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. Structural Health Monitoring of Large-Section Tunnel of Jingxiong High-Speed Railway Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Monitoring Technology. Laser Optoelectron. Progress, 57(21), 210603. https://doi.org/10.3788/LOP57.210603 (2020).

Wang, T., Shi, B. & Zhu, Y. Structural monitoring and performance assessment of shield tunnels during the operation period, based on distributed optical-fiber sensors. Symmetry 11(7), 940. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11070940 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Self-sensing ultra-high performance concrete: a review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 35, 032003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/ad092d (2023).

Chen, P-W. & Chung, D. D. Carbon fiber reinforced concrete for smart structures capable of non-destructive flaw detection. Smart Mater. Struct. 2, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/2/1/004 (1993).

Song, F., Li, Q. & Xu, S. A review of self-sensing ultra-high performance concrete: towards next-generation smart structural materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 145, 105350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105350 (2024).

Sun, M-Q. et al. Development of cement-based strain sensor for health monitoring of ultra high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 65, 630–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.105 (2014).

Hou, Y-Y., Sun, M-Q. & Chen, J-Z. Electrical resistance and capacitance responses of smart ultra-high performance concrete with compressive strain by DC and AC measurements. Constr. Build. Mater. 327, 127007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127007 (2022).

Qiu, L. et al. Self-sensing ultra-high performance concrete for in-situ monitoring. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 331, 113049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2021.113049 (2021).

You, I. et al. Electrical and self-sensing properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete with carbon nanotubes. Sensors 17(11), 2481. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17112481 (2017).

Le, H. V. et al. Enhancing self-stress sensing ability of smart ultra-high performance concretes under compression by using nano functional fillers. J. Building Eng. 44, 102717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102717 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Study on mechanical properties and self-sensing properties of sprayed high-performance concrete containing glass aggregate. Front. Mater. 10, 1320584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2023.1320584 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Optimization of performance index of self-sensing spray reactive powder concrete based on response surface methodology. Mater. Lett. X. 13, 100120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlblux.2021.100120 (2022).

GB175-2007. General-purpose Silicate Cement (Chinese Standard, 2007).

GB/T51003. 2014 Technical Specification for the Application of Mineral Admixtures (Chinese Standard, 2014).

GB/T2419-2005. Method for Determination of Cementitious Sand Fluidity (Chinese Standard, Beijing, 2005).

JGJ52-2006. Standard for Quality and Test Methods of Sand and Stone for Ordinary Concrete (Chinese Standard, 2006).

GB/T50081-2019 Standard Test Methods for Physical and Mechanical Properties of Concrete. Chinese Standard, Beijing, China. (2019).

SL/T352. 2020 Test Procedure for Hydraulic Concrete (Chinese Standard, 2020).

Pourbaba, M. et al. Effect of age on the compressive strength of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 175, 402–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.203 (2018).

Güneyisi, E. et al. Strength, permeability and shrinkage cracking of silica fume and metakaolin concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 34, 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.02.017 (2012).

Golewski, G. The role of pozzolanic activity of siliceous fly ash in the formation of the structure of sustainable cementitious composites. Sustain. Chem. 3(4), 520–534. https://doi.org/10.3390/suschem3040032 (2022).

Yang, J., Chen, B. & Nuti, C. Influence of steel fiber on compressive properties of ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 302, 124104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124104 (2021).

Wu, Z. et al. Effects of steel fiber content and shape on mechanical properties of ultra high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 103, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.11.028 (2016).

Tamanna, N., Tuladhar, R. & Sivakugan, N. Performance of recycled waste glass sand as partial replacement of sand in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 239, 117804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117804 (2020).

Larsen, I. L. & Thorstensen, R. T. The influence of steel fibres on compressive and tensile strength of ultra high performance concrete: a review. Constr. Build. Mater. 256, 119459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119459 (2020).

Yoo, D-Y. et al. Effects of fiber shape, aspect ratio, and volume fraction on flexural behavior of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced cement composites. Compos. Struct. 174, 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruct.2017.04.069 (2017).

Lee, N. et al. Relationship between three-dimensional steel fiber statistics and electromagnetic shielding effectiveness of high-performance, fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Materials 13(22), 5125. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13225125 (2020).

Allam, H. et al. About the self-sensing behavior of smart concrete and its interaction with the carbon fiber percolation status, sand connectivity status and grain size distribution. Constr. Build. Mater. 324, 126609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126609 (2022).

Dong, S. et al. Super-fine stainless wires enabled multifunctional and smart reactive powder concrete. Smart Mater. Struct. 28(12), 125009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/ab4eaf (2019).

Ding, Y. et al. Effect of steel fiber and carbon black on the self-sensing ability of concrete cracks under bending. Constr. Build. Mater. 207, 630–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.160 (2019).

GB50010. 2010 Code for the Design of Concrete Structures (Chinese Standard, 2010).

Idir, R., Cyr, M. & Tagnit-Hamou, A., Ingénierie, Développement Use of waste glass in cement-based materials. Environnement. https://doi.org/10.4267/dechets-sciences-techniques.3132 (2010).

Du, H. & Tan, K. H. Effect of particle size on alkali–silica reaction in recycled glass mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 66, 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.092 (2014).

Rajabipour, F., Maraghechi, H. & Fischer, G. Investigating the alkali-silica reaction of recycled glass aggregates in concrete materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 22(12), 1201–1208. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000126 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the reviewers for their valuable feedback and suggestions aimed at enhancing the paper’s quality; This research was funded by the Science Technology Department Program of Jilin Province (grant numbers, 20220203056SF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing–review and editing. S.W. Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology Writing–original draft.Y.Z. Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. X.Q. Writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Wu, S., Zhang, Y. et al. Study on the mechanics and self-sensing properties of ultrahigh-performance shotcrete containing waste glass aggregates. Sci Rep 15, 2936 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86257-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86257-8