Abstract

The urban agglomeration in central Guizhou is located in a crustal deformation area caused by tectonic uplift between the Mesozoic orogenic belt of East Asia and the Alpine-Tethys Cenozoic orogenic belt, with high mountains, steep slopes, fractured rock masses and a fragile ecological environment; this area is the most affected by landslides in Guizhou Province, China. In the past decade, there were a total of 613 medium and large landslide disasters, resulting in 137 deaths and a direct economic loss of 1.032 billion yuan. Therefore, this study selected 12 indicators from the topography, geological structure, and external inducing factors, and conducted factor collinearity analysis using the variance expansion coefficient to construct a landslide hazard assessment index system. The statistical analysis model was combined with a variety of machine learning models, and the selection of negative sample points was restricted in various ways to improve training data accuracy and enable machine learning model predictions with sufficiently supervised prerequisites. The accuracy of the model was validated by ROC curve analysis. The AUC values of the SVM, DNN, and bagging models were all greater than 0.85, indicating that the results were credible. However, the overall accuracy was SVM > DNN > Bagging; that is, SVM was more suitable for landslide hazard assessment of the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou. Finally, field surveys were used to validate multiple sites with historical landslides in extremely high-hazard areas and analyse their development characteristics. The evaluation results can provide strong guidance for engineering design, construction and disaster prevention decision-making of urban agglomeration in central Guizhou.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geological disasters refer to geological processes or phenomena that, under the action of the natural environment or human factors, cause the loss of human life and property and damage the environment25. The spatial–temporal distribution pattern is often the result of the joint action of humans and nature. The common types of geological disasters include landslides, collapses, debris flows, ground subsidence, and ground fissures. Disasters are complex and rapid, involving many factors, such as regional geological, hydrology, vegetation conditions and human activity intensity. China is a country with frequent geological disasters and severe disasters: there were 7840 geological disasters in 2020, including 4810 landslides, 1797 collapses and 899 debris flows; in 2021, there were 4772 geological disasters, including 2335 landslides, 1746 collapses, 374 debris flows; there were 5659 geological disasters in 2022, including 3919 landslides, 1366 collapses and 202 debris flows. As the type of geological disaster with the highest proportion, landslides have always been the focus of researchers, mainly on early identification3,23,58, susceptibility evaluation42,43 and hazard evaluation2,12. Disaster identification refers to the early screening of hidden landslide points using remote sensing, geophysical prospecting, and manual inspection. Susceptibility assessment, the most basic research work in landslide disaster assessment, refers to the static investigation of the likelihood of disasters occurring in a relatively stable disaster-conceiving environment based on topographic and geological conditions. Hazard assessment involves adding external inducing factors such as rainfall and road network density on the basis of susceptibility assessment to perform a more in-depth expression of the likelihood of a disaster.

Previously, hazard, susceptibility, and risk evaluations were often used together to describe the possibility of geological disasters or the degree of damage that may be caused to society without a clear conceptual differentiation between the three. At the Sixth International Landslide Symposium, Hutchinson21 clearly defined landslide hazard assessment as the possibility of landslide occurrence within a specific time period and divided it into two methods: local and regional evaluations. Three study directions are separated. Based on this concept and previous studies, the development of landslide hazard assessment methods has undergone a progression from the theoretical foundation and technical refinement of deterministic approaches to the practical exploration of non-deterministic methods and the intelligent evolution driven by data-driven technologies.

Deterministic methods refer to the use of traditional mechanical models to evaluate landslide disaster hazards based on the physical mechanism of landslide occurrence; the main methods include the limit numerical simulation method and the limit equilibrium method. However, the traditional model is more suitable for specific single landslide studies because of its clear physical meaning, high accuracy requirements for the underlying physical parameters, difficulty obtaining data and lack of regional generalization of the research method. The development of this method can be divided into three stages: the theoretical foundation phase (1960–1970s), the application expansion phase (1970s to the end of the twentieth century), and the model optimization phase (twenty-first century to present). Representative research achievements include Newmark39 proposed the classic cumulative displacement theory and further calculated the permanent displacement of the slope body under seismic conditions, which was used as the basis for seismic landslide hazard zoning. Morgenstern35 proposed the limit equilibrium method, which can be used to solve the safety factor of side slopes with arbitrary shapes. Satio49 proposed the classic creep theory “Saito method” and used topography, geology, slope and other factors as simulation conditions to accurately calculate the time to slip for a specific side slope. Wilson56 used the Newmark model to carry out a hazard assessment of the slope area along the fault zone. Milesa34 calculated the landslide displacement value of the East Bay Mountains in San Francisco based on the Newmark model and used the GIS platform to compile the seismic landslide hazard distribution level figure. Based on the improvement of the existing Newmark model, Rathje44 proposed a complete probabilistic framework for assessing landslide displacement and completed the seismic landslide hazard assessment for the California region. Kumar24 used the limit equilibrium method as the theoretical basis. The minimum safety factor for a specific landslide body is obtained using the particle swarm optimization method, and a corresponding landslide hazard assessment system is developed based on the MATLAB platform.

Nondeterministic methods comprehensively consider the factors affecting landslide occurrence, such as slope, lithology, curvature, and vegetation coverage, and implement landslide hazard assessments through two means: knowledge- and data-driven methods. The knowledge-driven method is more subjective; the weight of each factor is more influenced by expert experience; the research results lack objectivity. Common implementation methods include the analytic hierarchy process, fuzzy mathematics, etc. In contrast, the data-driven approach involves performing statistical analysis on a large quantity of landslide sample data to identify patterns and calculate the hazard assessment results. This approach can effectively avoid subjective assessment of the weight values of the influencing factors, and the main implementation methods include the information value method and machine learning. The knowledge-driven methods can be divided into the experiential analysis stage (1970–1990s), the logical reasoning stage (1990s to the end of the twentieth century), and the integrated application stage (twenty-first century to present), with representative research achievements including: Al-Homoud4 combined Monte Carlo simulation technology with fuzzy mathematics theory and comprehensively considered geology, topography, precipitation, and drainage conditions. He proposed a side slope damage potential index, which can be used to determine the degree of slope stability. Yoshimatsu59 used the analytic hierarchy process to assign values to topographic factors in remote sensing images and to assess landslide hazards for all of Japan according to different scores. Cemiloglu11 conducted a landslide hazard assessment for Maragheh County by selecting factors such as elevation, altitude, slope, aspect, and rainfall, integrating them with GIS software, and utilizing a logistic regression model. The data-driven methods can be categorized into the emergence phase (1980–1990s), the exploration phase (1990s to the end of the twentieth century), and the intelligent optimization phase of driven models (twenty-first century to present), with representative studies including: Neuland38 used the binary discriminant analysis method to assess the hazard of 250 slopes in Germany based on indicators of geological processes, rock and soil lithology, and structural characteristics, Carrara10 used indicators such as slope gradient, slope height, and lithology to evaluate landslide hazard in the mountainous areas of central and southern Italy using multiple regression analysis and multivariate statistical models.. Based on a landslide cataloguing database, Akbar1 used an information value model to assess the hazard of the Kaghon area in Pakistan. Nanehkaran36,37 systematically elaborated on how to train a riverbank landslide hazard evaluation model based on remote sensing, geological, topographical, and hydrological data using artificial neural networks as the theoretical foundation. Mao30 introduced a series of hybrid machine learning predictive models, including SVM, RF, and FL, and integrated the TOPSIS method to assess landslide hazard in the surrounding areas of the basin.

In contrast, a data-driven approach is more objective and convenient when evaluating a nonspecific target. However, statistical analysis models cannot resolve the nonlinear relationships among disaster-prone factors well. In contrast, machine learning models have strong learning abilities but are computationally intensive and prone to overfitting. Therefore, in areas with complex geological structures and frequent landslides, a single model cannot be used for assessment; however, a variety of models need to be combined to improve the accuracy of assessment results. In addition, the division of the basic evaluation unit of the study area and the location selection of the negative sample points in machine learning are also topics of considerable controversy in the current research. A large evaluation unit size will cause information confusion and reduce accuracy, while a small size will affect efficiency and cause data redundancy; the short distance between the positive and negative sample points will cause the factor information of the sample dataset to be too large. These results are similar, affecting the model training accuracy. These are the directions that need to be investigated in follow-up studies.

As a rapidly growing economic sector in western China, the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou is also an important fulcrum for the implementation of the “two horizontal and three vertical” urbanization pattern and the implementation of national strategies such as the “One Belt, One Road” and “western development”. This study combines the information quantity method and a variety of different machine learning algorithms to evaluate the landslide hazard of urban agglomerations. It compares the accuracy of different models to determine the best evaluation result, which provides references for subsequent hazard prediction and prevention of landslide disasters in this area.

Overview and data preparation of the study area

Study area

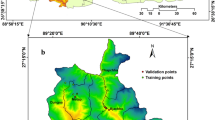

The urban agglomeration in central Guizhou is located in the central part of Guizhou Province, with a geographic location between 104°51′–108°12′E and 25°25′–28°29′N (Fig. 1). The overall terrain is high in the southeast and low in the northwest, with an average elevation of 1299 m. The average annual temperature is 15.3 °C, and the average annual precipitation is 1132 mm. Karst landforms in the territory account for more than 70% of the total area, with a complete range of morphologies, including karst fissures, karren formations, solution depressions and peak forests, with large undulations of the mountains, high depths of the canyons, and prominent environmental problems such as soil erosion, rock mass fracture and rocky desertification. Moreover, the risk of ecosystem degradation and natural disasters is high. This urban agglomeration is one of the 19 urban agglomerations planned in China, straddling five prefectures and cities, including 33 districts and counties, with a total area of approximately 54,000 square kilometres. The permanent population of this area in 2020 is 16.4347 million, and the GDP is 711.128 billion yuan, accounting for 67.71% of all of Guizhou Province. It is the core economic, cultural, and transportation area of Guizhou Province and has important location advantages and development potential.

Basic data sources

The main basic data used in this study included remote-sensing images, digital elevation models, geological maps, landslide disaster points, and meteorological raster data. The remote sensing images are from Landsat 9 OLI-2 on the USGS website (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) and were used for vegetation coverage calculation and selection of nonlandslide point samples in machine learning. The digital elevation model is from NASA (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/) and is used to extract slope, aspect, curvature, and TWI topographic moisture index. The 1:250,000 geological map and geological cross-section database are all from the Geological Cloud (https://geocloud.cgs.gov.cn/), which is used for lithology classification and calculating the distance to faults. The landslide hazard site data are from the Resources and Environmental Science and Data Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn/) and Chinese Qiyan Network (https://r.qiyandata.com), covering the period from 2004 to 2022. The meteorological data are from the China Meteorological Data Sharing Service Network (https://data.cma.cn/) and were interpolated by the data of each station. The vector data of administrative divisions, roads and water systems are from the National Geographic Information Resources Catalogue Service System (https://www/.webmap.cn/).

Methods

Information value model

As an evaluation method that combines information theory and statistics, the information value (IV) method was formally proposed by Shannon51 and used in the communication field. It was not until the 1980s that the concept of information entropy was accepted by researchers in the geological field and was applied to geological disaster assessment. Geological disasters are formed by the comprehensive action of geological tectonic, topographic and geomorphic factors. The information value model is based on probability statistics and comparative mapping theory after extracting the information contributed by each factor to the occurrence of geological disasters. The information value of each factor in the evaluation unit is combined and superimposed to obtain the total information value I. A larger I value indicates a greater probability of geological disasters. The basic formula is:

where I(Y, x 1 x 2...xn) is the amount of information provided by geological disasters under the combination of evaluation factors x 1 x 2...xn, P(Y, x 1 x 2...xn) is the probability of geological disaster under the combination of evaluation factors x 1 x 2…xn, and P(Y) represents the probability of geological disaster. This formula is a theoretical calculation model of information value. However, since it is difficult to accurately estimate the probability of geological disasters caused by each factor, the sample frequency method is used to calculate the total information value of the evaluation unit under each factor combination. Formula (1) can be expressed as:

where I is the total information value under n evaluation factor combination conditions, I(xi, A) represents the information value provided by the evaluation factor xi for geological disaster A and N is the total number of geological disasters in the study area. Ni is the number of evaluation factors xi in the study area, S is the total study area, and Si is the study area containing the evaluation factor xi.

Support vector machines

As a classification prediction model based on mathematical statistics, support vector machines (SVMs) were proposed by Vapnik54 and applied to linear problems. The basic principle is to construct an optimal separating hyperplane, and this plane is the closest to both sides. The sample point distance is maximized to achieve the classification of sample data. This model was not good at solving nonlinear problems in the early days. It was not until7 introduced the kernel function on the original basis and successfully solved the computational difficulty of nonlinear SVMs that this model was widely used in various fields. However, a nonlinear relationship exists between landslide disasters and each influencing factor, so that SVMs can be used.

For linearly inseparable data {xi,y i}, xi ∈ R d, yi ∈ {− 1, + 1}, R represents the real number, i is the number of samples, d is the dimension of the data, and nonlinear mapping φ (x) is needed. The original data are mapped to a feature space. φ ⋅φ (x) + b = 0 is the hyperplane equation; in this case, the classification interval is 2/||ω||. To make 2/||ω|| maximum, allowable ||ω||2 is the minimum, and the classification line must satisfy the constraint condition:

where ε i is a slack variable. When solving the classification hyperplane, the smaller the value of εi is, the better. Therefore, the original problem can be converted to solve the quadratic programming problem of the minimum value of ||ω||2/2 + C (∑εi) under the constraint of Eq. (3), where C is the penalty factor, and the discriminant function obtained from the solution is:

where K(xi,yj) = φ (xi) ⋅ φ(xj) is the kernel function. Currently, the commonly used kernel functions include polynomial, radial basis, linear kerels and sigmoid kernels.

Deep neural network

Deep neural networks (DNNs) were first proposed by Hinton18 and used in image processing. As an improved artificial neural network (ANN) algorithm, the two have similar network structures, both consisting of input, hidden, and output layers. However, the traditional ANN structure usually contains only one hidden layer, while DNNs can have as many as dozens of layers. Therefore, the DNN algorithm can perform more sufficient space mapping on complex data and handle nonlinear problems well, thus allowing the in-depth mining of the feature relationships between data.

The DNN model includes three parts: topological structure, activation function and loss function, and DNN training algorithm. The topological structure is also known as a multilayer perceptron. The constituent units of each layer are called neurons. The neurons are connected by weights ω, with an additional offset value b. The activation function is responsible for mapping the neuron input to the output end, and the activation function includes sign, sigmoid, tanh, ReLU, and maxout functions. The loss function is used to measure the distance between the DNN output result vector and the sample expectation vector. The commonly used functions are cross-entropy, mean square error, L1 loss, and L2 loss. The DNN training algorithms can adjust the connection weights and bias values to reduce the error value of the network output. The main methods include the backpropagation algorithm and stochastic gradient descent methods.

In the schematic diagram of the DNN model (Fig. 2), X1,X2, and Xn are the input values, b is the offset value of the neural unit in the hidden layer, w1, w2, and wn are the weight values, Y is the model output value, and the calculation formula is:

In Formula (5), g is the activation function and z is the linear relationship between the input end and the output end. In this study, ReLU was chosen as the activation function, and x represented the input information of the previous neuron. The formula is as follows:

Bagging trees

The bagging (bootstrap aggregation) algorithm, an integration algorithm in the machine learning field, was first proposed by Breiman8. The basic idea is to integrate multiple classifiers into a strong classifier. The implementation steps include self-service resampling of the original data, parallel training the sampled datasets, and outputting the fitting results (Fig. 3). The characteristic of the bagging algorithm is that each weak classifier has no interdependence and can run independently. Therefore, the final output model has low variance and a low probability of overfitting. The commonly used base classifiers include decision trees, logistic regression, and SVMs.

Results

Division of evaluation units

According to the “General Rules for Regional Environmental Geological Survey” promulgated by the China Geological Survey, the assessment units are divided into two main categories: (1) the study area is divided into many grid units with the same shape and size, and (2) The study area is divided into natural evaluation units of varying sizes using criteria such as physical geography, administrative divisions, or economic development units. This study chose the first method and referred to the existing empirical formula52:

where G s is the suggested value of the grid unit and S is the denominator of the scale of the study area. Based on the scale of the basic data. The basic size of the grid unit was 30 × 30 m, and a total of 60 010 660 grid units were divided.

Selection of evaluation indicators

Topographic and geomorphic factors

Topography and geomorphology impact on the occurrence, development, and evolution of geological disasters. Five relevant factors for the area, including slope, aspect, TWI, NDVI and plane curvature, were extracted based on the GIS platform. (1) Slope: This indicator is one of the key factors causing landslides. Figure 4e shows that with increasing slope angle, more frequent landslides occur15. (2) Slope aspect represents the projection direction of the slope surface from high to low. It affects ecological and environmental factors such as sunlight direction, thus affecting slope stability48. (3) TWI is a regional topography that has an important impact on the runoff flow direction57. (4) NDVI is related to soil structure stability20. Figure 4b shows that most landslides occur in areas with low vegetation coverage. (5) Plane curvature: This indicator can reflect the topographic change rate of the slope in the horizontal direction and greatly impacts landslide development41.

Geological structure factors

Geological conditions are important internal factors for landslide occurrence, and height affects slope structure, accumulation type and sliding bed morphology. Two relevant factors, rock group and fault density, were selected for analysis. (1) Rock group: Different lithologies have different effects on the occurrence of landslides. For example, rocks with lower strength are more likely to slide and fall and are more affected by erosion and weathering16,17. The 138 rock groups in this area were divided into five types according to hardness: hard rock, relative soft rock, soft rock and very soft rock. As shown in Fig. 4g, landslides mostly occurred in the soft lithology zone. (2) Fault density: In comparison, the rocks around faults are less stable and more prone to landslides9,60.

Inducing factors

Geological disasters occur under the joint action of various factors, among which external inducing factors play an important role in landslide formation. Four relevant factors, precipitation, evaporation, road network density and river network density, were selected for analysis. (1) Precipitation: The infiltration of large amounts of rainwater will cause the saturation of the soil‒rock layer on the slope and the accumulation of water in the aquifer at the lower part of the slope increases the weight of the sliding mass triggering landslides45,53. (2) Evaporation: In a dry climate, increased evaporation on the slope reduces soil moisture and causes soil to shrink, causing larger cracks on the slope surface and increasing landslide probability46,47. (3) Road network density: Road construction requires filling and excavating natural slopes, which changes their original stress state, making them unstable and leading to destruction55. Figure 4k shows that when the road network density is greater than 0.8, the density of disaster points is the highest. (4) River network density: Rivers can erode slopes on both sides of the river under the prolonged river scouring, forming a free surface, and landslides will eventually form under the action of gravity on the slope5.

Collinearity analysis of factors

When collinearity exists among multiple evaluation factors, a change in one of the factors will lead to corresponding changes in one or more other factors, resulting in error and reducing the accuracy of the evaluation model40. This study used the variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess the collinearity between the factors quantitatively. When the VIF is greater than 10, the collinearity between the factors is high and should be addressed; when the VIF is less than 10, it is considered to be no collinearity among the factors22,27. As shown in Table 1, the VIF values of the slope and aspect were significantly greater than 10 among the 12 selected evaluation indicators, indicating that a high correlation existed between them. Figures 4 and 5 show that the slope aspect is significantly greater than 10. The information value of the factors was lower, and the disaster point density values corresponding to different slope aspects were more similar. Therefore, the slope aspect factor was excluded, and the remaining 11 indicators were substituted into the model to continue the landslide hazard assessment.

Selection and training of negative sample points

In the machine learning classification problem, both positive and negative sample points must fully reflect the actual situation to achieve optimal classifier performance. There were 1947 landslide disaster sites within the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou, that is, 1947 positive sample points. This study used a 1:1 ratio and selected 1947 nonlandslide hazard sites to form the final sample dataset (Fig. 6). The selection rules are as follows:

-

(1) To improve nonlandslide sample site accuracy, the 11 influencing factors were overlaid and calculated to obtain the evaluation results of the information value method. The natural break point method was used to divide them into different zones. The negative sample points were selected from extremely low-prone areas and low-prone areas.

-

(2) The geological structure of the landslide site was already in a state of instability, and the probability of a geological disaster occurring again was high; therefore, the distance between nonlandslide and landslide sites was greater than 500 m.

-

(3) To reduce the redundancy of feature information at negative sample points, the distance between nonlandslide sites was greater than 500 m.

We randomly selected 70% of the total sample dataset as training samples and 30% as testing samples. The GIS platform was used to assign the evaluation result of the information model to the attribute of each sample point and used it as the input parameter of machine learning. Model training was completed in MATLAB and Python.

Model evaluation and comparison

The evaluation results of the SVM, deep neural network and bagging tree models were classified by the natural break point method, and the division intervals were consistent with those of the information value method: extremely low hazard, low hazard, moderate hazard, high hazard and extremely high-hazard; the results are shown in Fig. 7. In general, the hazard evaluation results calculated by the three models have high similarity. The high-hazard and extremely-high-hazard areas are mainly distributed in the middle and the upper regions of the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou, which is the central hub of the urban agglomeration. The geological structure is complex, the faults are densely distributed, and human engineering activities are extremely frequent. The lithology of the lower-left area is fragile, and the topography is large. It is also a high-hazard and extremely high-hazard landslide area. The moderate-hazard area is mainly distributed on both sides of the high-hazard area due to the similarity in geological structure. The low-hazard and extremely low-hazard areas are mainly distributed in the southern and western regions, where lithology is stable, and human activity intensity and external factors such as precipitation and evaporation are low. Therefore, landslide disasters are relatively rare.

Table 2 lists the statistical results of the SVM, DNN and bagging models. From the perspective of disaster density, the three types of models included extremely low-hazard areas < , low-hazard area < , moderate-hazard area < , and high-hazard area < extremely-high-hazard area, showing a gradual increasing trend, which corresponds with the objective disaster occurrence pattern. According to the distribution of the number of landslide sites, the three types of models all exhibited extremely high-hazard areas < extremely low-hazard areas < low-hazard areas, moderate-hazard areas < high-hazard areas, the number of extremely-high-hazard areas was the lowest due to having the smallest zoning area; therefore, this area also corresponds with the actual distribution of landslide sites. From the perspective of hazard zoning areas, the prediction results of the three types of models revealed that low-hazard areas had the largest area; however, some differences existed in the zoning of the remaining types. SVM represented as extremely high-hazard areas < extremely low-hazard area < high-hazard area < moderate-hazard area < low-hazard area. DNN was extremely high-hazard areas < high-hazard area < moderate-hazard area < extremely low-hazard area < low-hazard area. Bagging represented an extremely low-hazard area < extremely high-hazard area < moderate-hazard area < high-hazard area < low-hazard area.

Model accuracy validation

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is widely used in model evaluation in the machine learning field and was promoted by Fawcett13 for in-depth interpretation. In this landslide hazard assessment, the horizontal axis of the ROC curve represents the probability of being misclassified for the land slope sites of different hazard levels. The vertical axis represents the probability of correctly classifying land slope sites. The area enclosed by the ROC curve and the horizontal axis is the area under the curve (AUC). The closer the AUC is to 1, the higher the classification accuracy of the model. The model comparison results are shown in Fig. 8. The AUC values of the SVM, DNN and bagging machine learning models under different hazard levels were all greater than 0.85, indicating that the three types of models had high classification accuracy. However, in general, the AUC values of the extremely low-hazard area, low-hazard area, moderate-hazard area, high-hazard area, and extremely high-hazard area are all SVM > DNN > bagging; therefore, the SVM model has higher accuracy and is more suitable for landslide hazard assessment of urban agglomeration in central Guizhou Province.

Discussion

In landslide hazard assessment research, regardless of whether the method is deterministic or nondeterministic, strict or not, the influence of human subjectivity is unavoidable in the evaluation process, which leads to deviation in model reliability and accuracy. Therefore, many scholars often attributed it to the lack of reasonable and comprehensive evaluation models and introduced new mathematical methods. However, geological disasters are complex geoscience events, and model evaluation results are not consistent. If an overall understanding of geological disasters, from disaster formation to disaster causes, is lacking, and overall thinking about the relationship between the occurrence of disaster events and the surrounding environment cannot be established. Introducing algorithms will also lead to biased evaluation results. In the course of this research, the following points are worth discussing.

Indicator selection and data acquisition

Selecting evaluation indicators is the most important step in landslide hazard assessment. Additionally, different combinations of factors will lead to different assessment results33. At present, indicator selection is carried out using expert experience and subjective judgement. The differences between different studies lie in including subsequent factor correlation analysis, factor quantification and normalization, and data accuracy improvement14. This study used the VIF for factor screening. The Pearson correlation coefficient and the grade point average29,50 are commonly used. Whether different methods of factor collinearity analysis affect the final model evaluation result can be studied in the future. Considering factors with high-dimensional characteristics, the data are excessively redundant, and the calculation cost is high. Therefore, it is necessary to discretize the continuous disaster factors and unify the format for the convenience of subsequent evaluation; however, different discretization values will also affect the evaluation results. Additionally, some input data needed for direct or indirect evaluation are from planar maps, such as topographic maps and geological maps, such as geological elements, including soft interlayers and weak bases26, which often have a great impact on slope stability, however, it is difficult to reflect this role in the floor plan.

Division of evaluation units

The commonly used assessment units in landslide hazard assessment include slope and grid units6,19. In the former case, the study area should be divided into slope units based on geomorphic theory and the hydrological analysis model, however, this will increase calculation complexity and the uncertainty of the model evaluation results. In contrast, dividing the grid units is simple, and the calculation is straightforward. The scale bar of the sample data and the size of the study area should be appropriately selected; however, this would separate the inherent internal relationships of the slope system. Both have their advantages; however, it is difficult to choose. This can be considered an important proposition for comparative study in the future.

Model selection

Landslides are complex geological problems that cannot be explained by statistical analysis models alone28. In contrast, machine learning has a strong learning ability and can integrate landslide hazard assessment into a simple classification problem. Therefore, a supervised machine learning method can be used to mix a statistical model with a machine learning model to improve the accuracy of the evaluation results. This study used the evaluation result of the information model as the input parameter and called several machine learning models such as Bayesian, logistic regression, KNN, RF, bagging, SVM, BP neural network, and DNN. Finally, the model with the highest accuracy among SVM, DNN and bagging was selected for result analysis. However, in this process, we did not perform in-depth parameter tuning or algorithm optimization for a single algorithm, therefore, the accuracy of future models can be further improved.

Sample cleaning and dataset construction

When extracting the discrete values of the evaluation indicators based on historical landslide sites, there may be some blank values (0) or anomalous values (9999). This study used only the average value of the pixel size 3 × 3 neighbourhood of the outlier point to replace the attributes, and the multiple smoothing methods were not compared. Therefore, the evaluation accuracy of the model may be further improved. During dataset construction, the selection rules of negative samples and the imbalance in the proportion of positive and negative samples will directly affect the evaluation accuracy of the model. Compared with the random generation method, selecting negative samples in this study was restricted in three ways; however, it is still possible to improve the quality of the dataset further.

Field investigation

In the geological disaster prevention policies of this region, small-scale landslide disaster sites are usually reported by lower-level administrative units and then handled independently; for large-scale landslide disaster sites, professional and technical personnel deploy a large quantity of slope deformation monitoring equipment around the sites to accurately monitor point positions. Based on the above landslide hazard assessment results, an area with extremely high hazard was screened, and 12 known landslide sites in this area were selected for field disaster investigation (Fig. 9). Currently, three field situations exist: (1) Large-scale historical landslide sites. The characteristics of the slope are a long movement distance, wide area, severe damage to surface soil and vegetation, exposed bedrock, and severe damage to the ecological environment. This type of disaster point is extremely harmful to residential areas and roads at the slope foot. (2) Landslide sites are difficult to find. Because the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou is a mountainous area with lush vegetation, this type of landslide occurs in the middle of the forest and is not easy to detect manually; however, they will not cause damage to the socioeconomy or residential property. This type of landslide site also indirectly reflects that the NDVI can be used only as an important factor in landslide hazard assessment and does not play a decisive role. (3) Disappearance of disaster sites. Due to road construction of different grades, the expansion of residential houses and the development of tourist attractions, some small landslide sites have been artificially managed by terrain adjustment, surface reinforcement, and crop cover. Although this type of landslide site has disappeared or only some remaining traces are present, the surrounding lithology, fault distribution, and hydrometeorological conditions have changed very little, and the possibility of a subsequent occurrence remains. Therefore, it is still a high-hazard area according to the assessment results.

Future prospects

To further optimize the model, big data technologies can be leveraged to obtain massive high-resolution information from historical remote sensing data, landslide records, and environmental monitoring data. This approach enhances the quality of input parameters, improves feature selection, and elevates dataset quality31,32. Additionally, advanced deep learning algorithms or hybrid optimization techniques, such as Deep Belief Networks (DBN) and neuro-fuzzy systems integrated with evolutionary algorithms, can be introduced to strengthen the model’s ability to capture complex nonlinear relationships36,37. In practical applications, the model can be deeply integrated with GIS systems to combine evaluation results with real-time data on rainfall, human activities, and surface deformation. This allows for dynamic updates of landslide susceptibility maps, enabling precise disaster response in specific regions, and providing robust support for community safety and sustainable infrastructure development.

Conclusions

This study combined a statistical analysis model with a machine learning model and selected 11 indicators, such as the DEM, NDVI, and TWI, to assess the global landslide hazard of the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou. The specific innovations and findings are as follows:

-

(1) The upper-middle and lower-left areas of the urban agglomeration were the extremely high-hazard and high-hazard landslide areas, respectively. The low-hazard areas and the extremely low-hazard areas were mainly distributed in the southern and western regions, respectively. The remaining areas were considered moderate-hazard areas. Regional governments with different hazard levels need to adopt corresponding disaster prevention measures to protect the safety of people and property.

-

(2) The variance expansion coefficient was used to carry out collinearity diagnosis on the evaluation indicators. There was a high correlation between the slope and aspect in this area. After comprehensive consideration of the information value and the disaster point density of the two indicators, those with less influence were excluded. The slope aspect factor and follow-up work should be continued to reduce the evaluation model error effectively.

-

(3) After the low-landslide-hazard area is preliminarily identified based on the information value model, the negative sample points are randomly selected, and the distances between the negative sample and positive sample points and between each negative sample point are equal. A distance greater than 500 metres can effectively improve the overall sample dataset quality.

-

(4) The output values of the statistical analysis model were used as the input values of the SVM, DNN, and bagging machine learning models to achieve the machine learning model prediction with sufficient supervision. The AUC values of the three model types were all greater than 0.85, indicating excellent classification performance. However, the overall accuracy was SVM > DNN > bagging, indicating that SVM is more suitable for landslide hazard assessment of the urban agglomeration in central Guizhou. It also shows that combining and comparing different methods can improve the accuracy and stability of landslide hazard assessment.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Akbar, T. A. & Ha, S. R. Landslide hazard zoning along Himalayan Kaghan Valley of Pakistan-by integration of GPS, GIS, and remote sensing technology. Landslides 8(4), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-011-0260-1 (2011).

Alex, S. & Scott, M. Individual risk evaluation for landslides: Key details. Landslides 19(4), 977–991. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-021-01838-8 (2021).

Ali, M. F., Biswajeet, P., Shattri, M., Zainuddin, M. Y. & Ahmad, F. A. A hybrid model using machine learning methods and GIS for potential rockfall source identification from airborne laser scanning data. Landslides 15(9), 1833–1850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-018-0990-4 (2018).

Al-Homoud, A. S. & Al-Masri, G. A. An expert system for analysis and design of cut slopes and embankments. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 1(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.V.2.157 (1999).

Arabameri, A., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Yamani, M. Applying different scenarios for landslide spatial modeling using computational intelligence methods. Environ. Earth Sci. 76(24), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-7177-5 (2017).

Baeza, C., Lantada, N. & Moya, J. Influence of sample and terrain unit on landslide susceptibility assessment at La Pobla de Lillet, Eastern Pyrenees Spain. Environ. Earth Sci. 60(1), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-009-0176-4 (2010).

Boser, B. E., Guyon, I. M., Vapnik, V. N. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers. In Proceedings of the fifth annual workshop on computational learning theory, Association for Computing Machinery, pp 144–152 (New York, NY, 1992).

Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 24(2), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00058655 (1996).

Bucci, F., Santangelo, M., Cardinali, M., Fiorucci, F. & Guzzetti, F. Landslide distribution and size in response to Quaternary fault activity: The Peloritani Range, NE Sicily Italy. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 41(5), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3898 (2016).

Carrara, A. Multivariate models for landslide hazard evaluation. J. Int. Assoc. Math. Geol. 15(3), 403–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01031290 (1983).

Cemiloglu, A., Zhu, L., Mohammednour, A. B., Azarafza, M. & Nanehkaran, Y. A. Landslide susceptibility assessment for Maragheh County, Iran, using the logistic regression algorithm. Land 12(7), 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071397 (2023).

Cui, P., Zhu, Y., Han, Y., Chen, X. & Zhuang, J. The 12 May Wenchuan earthquake-induced landslide lakes: Distribution and preliminary risk evaluation. Landslides 6(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-009-0160-9 (2009).

Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 27(8), 861–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2005.10.010 (2006).

Fang, R., Liu, Y. & Huang, Z. A review of regional landslide hazard evaluation methods based on machine learning. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard Control 32(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.16031/j.cnki.issn.1003-8035.2021.04-01 (2021).

Gorokhovich, Y., Machado, E. A., Melgar, L. I. G. & Ghahremani, M. Improving landslide hazard and risk mapping in Guatemala using terrain aspect. Nat. Hazards 81(2), 869–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-2109-8 (2016).

Guzzetti, F., Cardinali, M. & Reichenbach, P. The influence of structural setting and lithology on landslide type and pattern. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 2(4), 531–555. https://doi.org/10.2113/gseegeosci.II.4.531 (1996).

Henriques, C., Zêzere, J. L. & Marques, F. The role of the lithological setting on the landslide pattern and distribution. Eng. Geol. 189, 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.01.025 (2015).

Hinton, G. E. & Salakhutdinov, R. R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 313(5786), 504–507. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127647 (2006).

Huang, F. et al. Efficient and automatic extraction of slope units based on multi-scale segmentation method for landslide assessments. Landslides 18(11), 3715–3731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-021-01756-9 (2021).

Huang, F., Chen, L., Yin, K., Huang, J. & Gui, L. Object-oriented change detection and damage assessment using high-resolution remote sensing images, Tangjiao Landslide, Three Gorges Reservoir China. Environ. Earth Sci. 77(5), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-018-7334-5 (2018).

Hutchinson, J. N. Landslide hazard assessment. Keynote paper. In Proceeding of 6th international symposium on landslides (ed. Bell, D. H.) 1805–1841 (Balkema, 1995).

Jing, C. et al. Variance inflation model for GNSS/accelerometer fusion deformation monitoring. J. Geodesy Geodyn. 43(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.14075/j.jgg.2023.05.0.10 (2023).

Kamila, P. Landslide features identification and morphology investigation using high-resolution DEM derivatives. Nat. Hazards 96(1), 311–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3543-1 (2018).

Kumar, V., Burman, A., Himanshu, N. & Gordan, B. Rock slope stability charts based on limit equilibrium method incorporating generalized Hoek-Brown strength criterion for static and seismic conditions. Environ. Earth Sci. 80(6), 212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09498-6 (2021).

Li, T. Disaster geology (Beijing Publishing House, 2002).

Liu, J. et al. Formation and chemo-mechanical characteristics of weak clay interlayers between alternative mudstone and sandstone sequence of gently inclined landslides in Nanjiang, SW China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 79(9), 4701–4715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-01859-y (2020).

Liu, M. The solution to multicollinearity: A new standard for eliminating variables. Stat. Decis. 5(2), 82–83. https://doi.org/10.13546/j.cnki.tjyjc.2013.05.012 (2013).

Liu, Z., Shao, J., Xu, W., Chen, H. & Shi, C. Comparison on landslide nonlinear displacement analysis and prediction with computational intelligence approaches. Landslides 11(5), 889–896. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-013-0443-z (2014).

Lucchese, L. V., de Oliveira, G. G. & Pedrollo, O. C. Attribute selection using correlations and principal components for artificial neural networks employment for landslide susceptibility assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7968-0 (2020).

Mao, Y. et al. Utilizing hybrid machine learning and soft computing techniques for landslide susceptibility mapping in a drainage basin. Water 16(3), 380. https://doi.org/10.3390/w16030380 (2024).

Mao, Y. et al. A MapReduce-based K-means clustering algorithm. J. Supercomput. 78(4), 5181–5202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-021-04078-8 (2022).

Mao, Y., Licai, Z., Feng, L., Nanehkaran, Y. A. & Zhang, M. Azarshahr travertine compression strength prediction based on point-load index (Is) data using multilayer perceptron. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 20807. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46219-4 (2023).

Meten, M., PrakashBhandary, N. & Yatabe, R. Effect of landslide factor combinations on the prediction accuracy of landslide susceptibility maps in the Blue Nile Gorge of Central Ethiopia. Geoenviron. Disasters 9(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-015-0016-7 (2015).

Miles, S. B. & Ho, C. L. Rigorous landslide hazard zonation using Newmark’s method and stochastic ground motion simulation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 18(4), 305–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0267-7261(98)00048-7 (1999).

Morgenstern, N. R. & Price, V. E. The analysis of the stability of general slip surfaces. Geotechnique 15(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1965.15.1.79 (1965).

Nanehkaran, Y. A. et al. Riverside landslide susceptibility overview: Leveraging artificial neural networks and machine learning in accordance with the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals. Water 15(15), 2707. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15152707 (2023).

Nanehkaran, Y. A. et al. Deep learning method for compressive strength prediction for lightweight concrete. Comput. Concr. 32(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.12989/cac.2023.32.3.327 (2023).

Neuland, H. A prediction model of landslips. Catena 3(2), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/0341-8162(76)90011-4 (1976).

Newmark, N. M. Effects of earthquakes on dams and embankments. Geotechnique 15(2), 139–160. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1965.15.2.139 (1965).

O’brien R.M., A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 41(5), 673–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9018-6 (2007).

Ohlmacher, G. C. Plan curvature and landslide probability in regions dominated by earth flows and earth slides. Eng. Geol. 91(2), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2007.01.005 (2007).

Perera, E. N. C., Jayawardana, D. T., Jayasinghe, P. & Manjula, R. Landslide vulnerability assessment based on entropy method: A case study from Kegalle district, Sri Lanka. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 5(4), 1635–1649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-019-00615-w (2019).

Pratap, R. & Vikram, G. Landslide hazard, vulnerability, and risk assessment (HVRA), Mussoorie township, lesser himalaya, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 24(1), 473–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01449-2 (2022).

Rathje, E. M. & Saygili, G. Probabilistic seismic hazard analysis for the sliding displacement of slopes: Scalar and vector approaches. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 134(6), 804–814. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2008)134:6(804) (2008).

Ray, R. L. & Jacobs, J. M. Relationships among remotely sensed soil moisture, precipitation and landslide events. Nat. Hazards 43(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-006-9095-9 (2007).

Reder, A., Rianna, G. & Pagano, L. Physically based approaches incorporating evaporation for early warning predictions of rainfall-induced landslides. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 18(2), 613–631. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-18-613-2018 (2018).

Rianna, G., Reder, A. & Pagano, L. Estimating actual and potential bare soil evaporation from silty pyroclastic soils: Towards improved landslide prediction. J. Hydrol. 562, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.05.005 (2018).

Ruff, M. & Czurda, K. Landslide susceptibility analysis with a heuristic approach in the Eastern Alps (Vorarlberg, Austria). Geomorphology 3(94), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.10.032 (2008).

Saito, M. Research on forecasting the time of occurrence of slope failure. Q. Rep Rtri 10(3), 135–142 (1969).

Sandeep, C. S. & Senetakis, K. The tribological behavior of two potential-landslide saprolitic rocks. Pure Appl. Geophy. 175(12), 4484–4499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-018-1939-1 (2018).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27(3), 379–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x (1948).

Tang, G., Liu, X. & LV, G.,. The principles and methods of digital elevation models and geospatial analysis (Science Press, 2005).

Uwihirwe, J., Hrachowitz, M. & Bogaard, T. A. Landslide precipitation thresholds in Rwanda. Landslides 17(10), 2469–2481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-020-01457-9 (2020).

Vapnik, V. N. A note on one class of perceptrons. Automat. Rem. Control 25, 821–837 (1964).

Wang, X., Zhang, L., Wang, S. & Lari, S. Regional landslide susceptibility zoning with considering the aggregation of landslide points and the weights of factors. Landslides 3(11), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-013-0392-6 (2014).

Wilson, R. C. & Keefer, D. K. Dynamic analysis of a slope failure from the 6 August 1979 Coyote Lake, California, earthquake. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 73(3), 863–877. https://doi.org/10.1785/BSSA073003086 (1983).

Xu, C., Xu, X., Zhou, B. & Sheng, L. A study on the probability of co seismic landslides: A new generation of seismic landslide hazard model. J. Eng. Geol. 27(5), 1122–1130. https://doi.org/10.13544/j.cnki.jeg.2019084 (2019).

Yan, L. et al. Integrated methodology for potential landslide identification in highly vegetation-covered areas. Remote Sens. 15(6), 1518. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15061518 (2023).

Yoshimatsu, H. & Abe, S. A review of landslide hazards in Japan and assessment of their susceptibility using an analytical hierarchic process (AHP) method. Landslides 3(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-005-0031-y (2006).

Zhang, Y., Chen, G., Zheng, L., Li, Y. & Wu, J. Effects of near-fault seismic loadings on run-out of large-scale landslide: A case study. Eng. Geol. 166, 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2013.08.002 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Weiquan Zhao, Zulun Zhao, Liang Huang, and Wei Li for their help in the field work.

Funding

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript. This research was supported by Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science) (Nos. ZK [2024] General 628), Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science) (Nos. ZK [2022] General 277), Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program (Nos. [2023] General 202) and the Youth Foundation Project of Guizhou Academy of Sciences (Nos. [2024] 13).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junhua Luo and Weiquan Zhao codesigned the research methods and implementation process. The material preparation, data collection and analysis were completed by Junhua Luo, Liang Huang, and Wei Li. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Junhua Luo, and Zulun Zhao and Weiquan Zhao participated in the subsequent revisions of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, J., Zhao, Z., Li, W. et al. Landslide hazard assessment of an urban agglomeration in central Guizhou Province based on an information value method and SVM, bagging, DNN algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 2483 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86258-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86258-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multi-scale risk assessment method for pipeline slope hazards

Journal of Mountain Science (2025)