Abstract

This study develops the you only look once segmentation (YOLOSeg), an end-to-end instance segmentation model, with applications to segment small particle defects embedded on a wafer die. YOLOSeg uses YOLOv5s as the basis and extends a UNet-like structure to form the segmentation head. YOLOSeg can predict not only bounding boxes of particle defects but also the corresponding bounding polygons. Furthermore, YOLOSeg also attempts to obtain a set of better weights by combining with several training tricks such as freezing layers, switching mask loss, using auto-anchor and introducing denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPM) image augmentation. The experiment results on the testing image set show that YOLOSeg’s average precision (AP) and intersection over union (IoU) are as high as 0.821 and 0.732 respectively. Even when the sizes of particle defects are extremely small, the performance of YOLOSeg is far superior to current instance segmentation models such as mask R-CNN, YOLACT, YUSEG, and Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation. Additionally, preparing the training image set for YOLOSeg is time-saving because it needs neither to collect a large number of defective samples, nor to annotate pseudo defects, nor to design hand-craft features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dies embedded on a wafer need to be inspected for defects before packaging to ensure product quality, chiefly by visual inspection (VI) or automated optical inspection (AOI). However, as for the VI, inexperienced operators may miss or overkill defects, compounded by the fact that their standards for detecting defects can vary more than those of experienced operators. The AOI system is easily disturbed by the surrounding environment, such as light source attenuation, surge, and vibration, which affect the inspection results. In addition, the algorithm of the machine is often customized, and the features used for image recognition must be manually described by experts, which often cannot be generalized when dies or wafers with various types of appearances are inspected. This is the reason why researchers have attempted to incorporate deep learning models into defect inspection systems in recent years. Because deep learning models automatically extract features, the design of the algorithms can be feature-free and may be generalized, leading to a certain degree has invariance against interference such as translation and rotation.

Factory workers often lack time to collect defect samples, and they need to spend a lot of time and manpower on defect annotation. Therefore, the first contribution of the method proposed in this study is to meet the needs of image augmentation through the denoising diffusion probabilistic models (DDPM)1. By generating pseudo defective images, both the number of images and the diversity of defects can be increased, enabling the model to learn more defect features, to improve the ability of the model itself to segment defects, and to alleviate the burden of collecting a large number of training images. However, while DDPM can generate pseudo images, it does not provide corresponding annotation files. Based on this, the second contribution of this study is the auto-annotation for pseudo defects through digital image processing (DIP) procedures. The combination of DDPM and DIP enables the generation of image sets and annotation sets that can be used to train models, saving the cost of sample collection and the cost of defect annotation.

Besides image augmentation, the third contribution of this study is to propose a novel you only look once segmentation (YOLOSeg) model that can detect and segment small defects. YOLOSeg is based on the you only look once, version 5 s (YOLOv5s) object detection model, aiming to obtain the predictive bounding boxes of the defects, which facilitates identifying the locations and sizes of the defects. Additionally, it has a UNet-like model architecture, which obtains the predictive bounding polygons of defects, and further delineates the contours of defects. To sum up, YOLOSeg is an instance segmentation model because it can predict not only the bounding boxes but the bounding polygons of the targeted objects.

The rationale to develop YOLOSeg is that the die particle defects in this study are quite small. There is a need to measure the area of those small defects in practice because it provides information to the traceability system to track and trace along the manufacturing process. When using current instance segmentation models, such as the mask regional-based convolutional neural networks (mask R-CNN)2, the you only look at coefficients (YOLACT)3, the segmenting objects by locations (SOLO)4, the YUSEG5, or the Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation (https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5) to segment small particle defects, they often encounter serious mis-detection problems, which affects the prediction performance. In this study YOLOSeg makes good use of multi-scale detection, which performs defect segmentation at various scales on the feature maps extracted and integrates the information of the bounding boxes and the bounding polygons into the loss function. As a result, the end-to-end training is achieved. Thus, the quality of the die appearance could be checked.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Firstly, the existing literature on wafer inspection and the applications of generative model based image augmentation in different defect inspection cases are reviewed in Sect. “Literature Reeviw”. Sect. “Methodology” describes the proposed methodology which includes the image-capturing hardware, the DDPM and the auto-annotation mechanism, and the model proposed YOLOSeg. Section “Results and analysis‘‘ presents the experimental results of a real-world die defect inspection problem. A model spot checking experiment is conducted to show the designing rationale of proposed YOLOSeg structure. Training tricks are suggested according to ablation studies. The defect segmentation results and comparative analysis are also exhibited. The concluding remarks and suggestions for future study are discussed in Sect. “Conclusion”.

Literature review

Generally, available die or chip defect inspection techniques could be the golden template matching method, the design-rule checking method, machine learning, and deep learning. The golden template matching method reveals pixel-wise difference between the image to be inspected and the pre-established golden template, where the significant difference indicates the potential defects. However, alignment issues must be addressed before running this method. When running the design-rule checking method, engineers must manually describe the geometric and textural features of each component according to the die or chip structure, component appearance and defect appearance. Then they design a series of detecting logic for the defects as well as the category to which the defects belong. Machine learning is mainly to establish the mapping relationship between die/chip features and defect categories through supervised learning. However, the design-rule checking method, machine learning need to design another completely different feature when the die/chip geometric features or appearances are greatly different, which may result in time-consuming operation.

Literature on wafer and die/chip defect segmentation

In recent years, the application of deep learning to wafer, die or chip defect detection has attracted widely attention6. This is mostly because the models eliminate manual feature extraction, and the model trained is resistant to shift, rotation, exposure, and noise. Therefore, deep learning-related models have been utilized to solve problems like defect classification, detection, and segmentation7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 on wafers, dies, or chips. Among these three task, classification methods identify whether an image contains defects or not, but they cannot provide information on the exact location and extent of the defects. Although defect classification seems relatively easy, it is not easy to achieve in practice. The reason is that the area of defects on an image is often much smaller which makes it difficult to achieve a satisfactory classification accuracy. Detection methods further identify where the defects are located. But they not only ignore the issue of object angles but also often result in overlapping bounding boxes for adjacent defects. On the other hand, segmentation methods provide a more detailed and accurate representation of the defects’ contours, enabling a more precise analysis of defects’ shape, size, and location. Wen et al. proposed a die defect segmentation method, in which the feature maps were first generated by feature pyramid networks with atrous convolution (FPNAC); then region proposals were generated with the region proposal network (RPN)13. Finally, the region proposals are mapped to the corresponding blocks and fed into the deep multi-branches neural network (DMBNN) for segmentation. Its mean pixel accuracy (MPA) was 93.97%, with the mean intersection over union (mIoU) at 83.58%. Tao et al. segmented the conductive particle defects in chips on glass substrate14. A multi-frequency feature learning CNN was proposed, comprising a UNet module, a multi-frequency module (MFM), and an active contour without edge (ACWE) loss function. It aimed to enhance multi-frequency feature fusion of conductive particles, to accelerate network training and to extract finer defect contour features. Experimental results showed that their method outperforms current mainstream models. The rate of precision, recall, and mIoU reached 92.71%, 90.95%, and 81.61%, respectively. Nakazawa and Kulkarni presented a method for detecting and segmenting abnormal wafer map defect patterns using an encoder-decoder architecture15. Synthetic wafer maps are used for training, validation, and testing, demonstrating the model’s capability to detect unseen defect patterns in real wafer maps. The results show that the proposed method effectively detects and segments defects, significantly enhancing the accuracy and reliability. Chiu and Chen proposed a method combining data augmentation and Mask R-CNN for classifying mixed-type wafer map defects16. Using real-world WM-811 K data, their approach enhanced defect pattern classification and segmentation by incorporating copy-paste and rotational augmentation techniques. The model achieved a single-type classification accuracy of 97.7%, with mixed-type classification showing 82% accuracy and a hamming loss of 0.155. Nag et al. introduced WaferSegClassNet (WSCN), a light-weight network designed for both classification and segmentation of semiconductor wafer defects17. Utilizing an encoder-decoder architecture and N-pair contrastive loss, WaferSegClassNet effectively handled single and mixed-type defects. It achieved high accuracy of 98.2% and Dice coefficient of 0.9999 on the MixedWM38 dataset. The model was significantly lighter at 0.51 MB and faster, requiring only 150 epochs to converge compared to state-of-the-art models. Wong used YOLOv5-segmentation to capture the region of interest (ROI) of the IC chip area18. This step was essential for isolating the chip accurately, allowing focused detection of defects like die rotations and cracks. The model performed well, achieving a high mean average precision (mAP) of 99.5%.

Based on the summarization of the above literature, classification methods identify whether an image contains defects or not, but they cannot provide information on the exact location and extent of the defects. Although defect classification seems relatively easy, it is not easy to achieve in practice. The reason is that the area of defects on an image is often much smaller which makes it difficult to achieve a satisfactory classification accuracy. Detection methods further identify where the defects are located. But they not only ignore the issue of object angles but also often result in overlapping bounding boxes for adjacent defects. On the other hand, segmentation methods provide a more detailed and accurate representation of the defects’ contours, enabling a more precise analysis of defects’ shape, size, and location. However, there is still room for improvement in the current methods’ ability to segment small defects. The proposed YOLOSeg has potential in detecting small die defects in semiconductor processes and can be a valuable addition to the field of defect analysis and quality control.

Literature on generative model based image augmentation for defect segmentation applications

Generative models, such as generative adversarial networks (GAN) and DDPM, have been instrumental in advancing artificial intelligence, particularly in their ability to generate realistic and diverse synthetic data. Goodfellow et al. proposed a prototype of GAN, which consists of a generator and a discriminator19. The generator randomly selects a real image from the image set and a pseudo image generated by a random number vector, whereas the discriminator interprets the authenticity of the pseudo image according to features of the real image. Through training and experience, the discriminator increases its ability to interpret the difference between the real and the pseudo images, making the generator try to generate more “realistic” pseudo images. Theoretically, the generator could ultimately generate very “real” pseudo images to the effect that it becomes difficult to distinguish the real image from the pseudo one. Thus, by continuous adversarial learning process between the two networks, it may be possible to create a better generative model. Ho et al. proposed a prototype of a DDPM, which consists of a forward and a reverse process1. In the forward process, Gaussian noise is gradually added to the original image over several steps, progressively making it resemble pure noise. In the reverse process, a neural network learns to reverse the noise additions. It predicts and subtracts the noise at each step, gradually reconstructing the original image from the noise.

With appropriate combinations with deep learning models, the generative models managed to significantly improve the prediction performance. Performing image augmentation through generative models is currently one of the most popular research topics. The idea is to add training images and to diversify the defect patterns by generating pseudo defective images, thereby improving the model’s prediction performance and avoiding overfitting during the training process. Auto-annotation algorithms could be beneficial after pseudo images are generated. Chen et al. developed a set of particle defect detection algorithms through YOLOv3 for defect detection, and utilized DIP to segment the primary and secondary axes of the defect, which served as a grading tool for die quality11. The experimental results showed that the pseudo defective images with size 64 × 64 generated by GAN archived 7.33% higher tested by AP. Tsai et al. worked on solar-power wafer patches (size 50 × 50 with heterogeneous textures)20. The first step was to augment the defective image set by two times through CycleGAN, and the second was to feed these image patches into a CNN model similar to LeNet structure for training. As for the inference, the experiment involved moving a 50 × 50 sliding window move upon the 500 × 500 original image. The experimental results showed that the pixel classification accuracy rate was 81.5%. De Ridder et al. introduced SEMI-DiffusionInst, a new framework for resist wafer defect classification and segmentation using a DDPM with size of 480 × 48021. This approach leveraged deep learning for precise defect inspection in SEM images, outperforming previous methods in both bounding box and segmentation accuracy by 3.83% and 2.10%, respectively. The study benchmarked various feature extractor networks, achieving notable improvements, especially in detecting line collapse and thin bridge defects. Wijaya et al. analyzed microstructure relationships in porous copper used in semiconductor wafers22. Their method integrated tomographic image acquisition, segmentation, feature extraction, and synthetic microstructure reconstruction. Using a UNet model, they achieved a segmentation accuracy of 95% and found that DDPM with size of 224 × 224 outperformed cGAN in generating realistic microstructure images, crucial for predicting material properties like electrical conductivity.

According to the literature review, the application of GAN and DDPM to semiconductors is an area that is still largely underexplored at present9,11. Furthermore, there is rare research combining DDPM image augmentation with defect segmentation models, which serves as the rationale for this research and may also constitute one of the contributions of this study. Because of its powerful generating ability and its stability23, this study chooses the DDPM to increase the diversity of defects. This is achieved by generating pseudo defective images, thereby saving time for sample collection of the defects.

Methodology

The overall process of this research is shown in Fig. 1. This section will introduce the image-capturing hardware, the physical image structure and manual annotation methods. Additionally, it will discuss the details of the YOLOSeg proposed in this study, the important training tricks of the YOLOSeg, post-processing methods, and the metrics used.

The hardware to capture die images and the manual annotation of defects

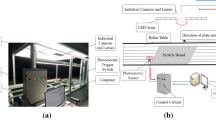

In this study, the imaging system shown in Fig. 2(a).11 captures images of the die surface. The charge-coupled device (CCD) model of this system is a Hitachi KP-FD202GV. The CCD is associated with an Olympus lens that has a 5X optical magnification. A 12 V/100W coaxial yellow light ring halogen lamp provides homogeneous lighting to highlight the surface features of the die. During imaging, each die is sequentially captured using an S-shaped scanning path controlled by a two-axis movement controller. The main pattern on the die is not exactly centered in the image to avoid overemphasizing positioning precision. Although a slight shift occurs, it is limited to a few pixels and does not affect the integrity of the die pattern. This slight shift between images renders the traditional golden template matching method inapplicable. Therefore, a deep learning method is suitable in this case thanks to its anti-shift ability.

The image-capturing system and the wafer die. (a) hardware configuration 11; (b) patch of a die; (c) manual annotation.

The partial patch of the wafer die surface in this study is shown in Fig. 2(b). Due to the non-disclosure agreement with the company that provided the image, the full picture of the wafer die cannot be shown, and Fig. 2(b) has been discolored. The die mainly includes a pad, an ion implantation zone, a bottom layer, etc. The pads are used to be contacted by probes for in-circuit-test (ICT) of the die. The ion implantation area is used to accelerate the ion electric field, so that high-energy ions could be implanted into the die to generate a photolithography pattern. The bottom layer is a thin film protective layer to prevent the components from moisture, corrosion and so on. During the manufacturing process of the wafer, the surface of the die will be polluted by the falling of particles. The shape, particle size and falling position of the particles are uncertain, whose appearances are generally dark.

After gathering the die image set, an annotation file for each image is prepared for model training. As shown in Fig. 2(c), Labelme is used to mark defects, with each vertex of the bounding polygon along the defect contour manually defined and assigned a class label. This coordinate and class data are saved in JSON format as ground truth and then converted to YOLO format to align with YOLOSeg model training requirements. These bounding polygons also allow us to derive the minimum bounding box for each defect, providing additional ground truth for assessing defect detection performance.

Small defect segmentation model: YOLOSeg

The structure of proposed YOLOSeg is shown in Fig. 3. The YOLOv5s structure in the YOLOv5 family is chosen as a base detection model. The backbone consists of a Focus layer, cross-stage-partial (CSP) with or without residual blocks (named CSP1n or CSP2n, respectively, where n represents the number of repetitions) and naïve convolution (Conv) layers. In the neck, a spatial pyramid pooling fast (SPPF) block and path aggregation network (PAN) are used for feature fusion. At the end of the model, three convolutional YOLOheads provide multi-scale anchor-based predictions. Information at the bottom of each feature map in Fig. 3 represents its spatial size as well as number of channels, respectively. In each YOLOhead, the spatial size is downsized to 32, 16, and 8 times and number of channels is 18 because number of defect classes is 1 and each of them has 3 anchors.

In addition to the object detection component of YOLOv5s, there is an auxiliary fully connected network called ProtoNet3. When combined with the detection head, this network completes the Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation architecture for instance segmentation24. In image segmentation, however, the main challenge lies in reconstructing the original image from a vector derived from the feature maps learned by the backbone25. The backbone of YOLOv5s is adapted to function as an encoder in a UNet-inspired structure. For the decoder, feature maps from the smallest scale of YOLOheads are chosen as the entry point. The neck structure of YOLOv5s enables a sophisticated fusion of semantic and fine-grained information. To facilitate information exchange at larger scales, additional shortcut connections between the encoder and decoder are incorporated. This structure is referred to as the UNEThead in YOLOSeg.

Specifically, a raw image passes through the backbone of the detection model and, simultaneously, is processed by a convolutional layer before entering the decoder to reduce the semantic gap. Two additional sets of feature maps are also extracted from the encoder at 304 × 304 and 152 × 152 scales for feature fusion within the decoder. The decoder first up-samples the input (initially 76 × 76) from the neck by a factor of two using a transpose convolution; the resulting feature maps are then concatenated with those from the encoder. This concatenated output is processed through a CSP bottleneck block with three CSP2n layers, a process that is repeated three times with progressively decreasing output channels. Finally, a depthwise convolution (DW Conv) is applied to produce the final prediction mask.

Notice that since coco.json, which is used for segmentation mAP computation, requires the same size of input image during training process for consistency. We train the detection part first. Then we train the segmentation part only by freezing the detection part. The total loss function consists of two components: one is the loss of YOLOv5s used for bounding boxes and classification; the other is a mask loss for segmentation. The formula for the total loss is given as follows:

Among them, Lossyolo includes the complete IoU (CIoU) loss that was used to measure the prediction performance of the position and size for the bounding box. In addition, Lossyolo includes the binary cross entropy (bce) loss with logits loss that was used to measure the prediction performance of the objectness for the bounding box. Note that because this study only predicts one class of defect, the item previously used by Lossyolo for predicting performance of the bounding box type is excluded here. ybbox and ŷbbox represent the ground-truth and prediction results of the bounding box, respectively. Lossmask mainly refers to dice loss, which is used to measure the prediction performance of the bounding polygon. ymask and ŷmask are the binary mask of ground-truth and the predicted mask, and α is the weight of mask loss. The larger the value is, the more important the contribution of the mask loss is.

Tricks for training the YOLOSeg

In the process of model training, YOLOSeg has several important training tricks that affect the performance of the prediction: such as implementing the freezing mechanism during training process, determining the type of loss function, using an auto-anchor mechanism during model initialization to automatically determine the default size of the anchor boxes, and last but not least, utilizing advanced image augmentation. The definition and purpose of each training trick are stated in the following.

1) The freezing mechanism during training process: When training YOLOSeg, it may be challenging to simultaneously learn the detection part and the segmentation part. Therefore, as a training trick, all network weights are initially learned. After achieving a stable loss value, the weights of the detection part are frozen, and only the weights of the segmentation part undergo fine-tuning. This process continues until the detection part has been able to properly detect the size and position of the defect. With a well-trained detection model, the decoder can then focus more effectively on transforming feature maps from neck and backbone into prediction mask.

2) Determine the type for Lossmask to segment small objects: Compared with the entire die image, the proportion of defects is very small. If traditional bce loss was used to measure the segmentation performance, it would come up with the issue of unbalanced classification. The study considers two loss functions that can improve the detection of small objects, including dice loss and combination of bce and dice loss (bce-dice). For bce loss, each pixel pair of the ground-truth mask and predicted mask is computed; that is,

where N is total number of pixels and i is the index of pixel. Since the defects to be detected only occupy a very small area of the entire die image, the mechanism of bce will guide the model to learn a large area of the background, resulting in low prediction performance26. Therefore, it is necessary to increase the weight of the defect area27. Dice loss is calculated as twice the ratio of the area of the intersection of the ground-truth and the predicted mask, and the total areas of them.

where ϵ is an extremely small value used for avoiding dividing by zero. Neither dice nor bce loss performed particularly well alone, so a combination loss function was implemented. The combination of bce and dice loss is the summation of both.

bce-dice loss has been proven to outperform bce or dice alone28. The main reason is that bce loss can guide dice loss in its learning process. If the defect segmentation result under an iteration is not within the range of indicated small defects at all, then the dice loss would be 0, and the correct gradient descent direction could not be learned. In this situation, with the help of bce loss, the network can find a learning direction.

3) Explore optimal anchor box default size: The default size of the 9 anchor boxes in YOLOSeg is learned from the COCO dataset, and the default anchor box width and height can be as large as 373 × 326 pixels, which may not be suitable for the image set of small defect detection in this study. Conceivably if the default size of the anchor box and the size of the detection target exist large differences, that will negatively influence performance of the defecting model. It is necessary to search for a proper default size of the anchor box through an automatic mechanism. First, perform k-means clustering through the width and height ground-truth of the anchor boxes in the training set to obtain centroids of the width and height of given number of anchor boxes. Then, the centroids are used as the initial condition of genetic evolution (GE) algorithm. The GE algorithm will perform several evolutions on all anchor boxes. During the process, the CIoU and the best possible recall (BPR) serve as the fitness function. After the evolution, if the fitness of a certain width and height combination improves, assign the result to the anchor box. If not, ignore it.

4) Image augmentation using DDPM: In the state-of-art object detection models, rich augmentation universally brings additional performance gain and provides robust model prediction when noise background is present. For defect detection, image quality is hardly changed significantly due to manufacturing requirements. Therefore, mosaic, flipping and affine transformation are turned off in the present implementation. In this study, the DDPM image augmentation is used to increase the number of training images and generate defects with rich appearance, which helps to work efficiently as shown in Fig. 4. However, it is too laborious for the DDPM to directly generate a complete wafer die defective image and it can only draw the approximate outline of the die. For this reason, this study refers to11’s generation strategy of “focusing solely upon the defects itself”. According to the auto-annotation procedure of11, only the coordinate information of the bounding box is provided in the annotation file, so the extracted defect patch contains redundant die background. This study attempts to make a difference. It fully uses the JSON annotation information corresponding to each training image, and then constructs a mask according to the contour of each defect. As might be expected, because the learning object is simplified, DDPM may easily generate a variety of “realistic” pseudo defects. Even when performing auto-annotation to the pseudo defects, since the white background and the gray pseudo defect sharply contrast each other’s brightness, the mask for extracting the pseudo defect may be feasible through the Otsu binarization. Later, randomly extract the pseudo defects, the embedded positions and the defect-free images, and one can embed pseudo defects in a certain coordinate position of the defect-free image, which ultimately creates the pseudo defective images and their corresponding annotation files.

Metrics for evaluating the model performance

Instance segmentation models often use mAP and mIoU to evaluate the model performance. The mAP is generally used to evaluate the performance of object detection, which measures the union of ground-truth bounding boxes and prediction bounding boxes divided by the intersection to obtain the patch-level IoU. When the patch-level IoU between a ground-truth bounding box and a prediction bounding box is greater than or equal to the AP IoU threshold, it represents a true positive (TP), which means accurate detection. If the patch-level IoU is smaller than the threshold, it represents false positive (FP), which means inaccurate detection. When the ground-truth box is not detected, it represents a false negative (FN). Next, sort by descending order the confidence of the prediction box, and calculate each precision and recall rate to draw the precision-recall curve (PR curve). The precision represents how many proportions in the prediction box are greater than the IoU threshold; the recall rate represents how many proportions in the ground-truth box are accurately detected. In addition, the AP is the area under the curve of the PR curve; the mAP is the average value of AP obtained by each object type.

On the other hand, mIoU is used to evaluate the prediction performance of object segmentation, which measures the union of ground-truth bounding polygons and prediction bounding polygons divided by the intersection to obtain pixel-level IoU. The average IoU value calculated after comparing the prediction results with the real ground-truth is the mIoU.

For there is only one class of defect to be detected in this study, the AP and the IoU are adopted as the metrics of performance evaluation. In this study, we AP@IoU = 0.5 is chosen as the primary metric for evaluating model performance. This decision is driven by the metric’s widespread acceptance and historical significance in the field of object detection. AP@IoU = 0.5 offers a balanced approach by considering a prediction correct if IoU with the ground truth is at least 0.5. This threshold is traditionally used as it represents a reasonable compromise between detection accuracy and tolerance for small localization errors, making it particularly suitable for practical applications where perfect alignment is less critical. Before evaluation, note that a post-processing of non-maximum suppression (NMS) and clear segmentation are used3. The NMS will find the one with the highest objectness from the predicted bounding boxes with a high overlap (defined by a NMS IoU threshold). The clear segmentation will consider the region of predicted mask within the bounding boxes only, and the other region is regarded as nothing, even if in actual the model may predict there is something there. The post-processing is shown in Fig. 5. We then use the result masks to compute the AP and the IoU.

Results and analysis

This section will first introduce the data material. Subsequently, a series of experiments on proposed YOLOSeg will be conducted. These include explaining the rationale of network structure, determining the training tricks, and demonstrating the perdition performance. The YOLOSeg has several key hyper-parameters. The YOLOSeg structure has an input shape of 608 × 608 × 3, with 3 anchors for each YOLOhead and an NMS IoU threshold of 0.45. The metric for YOLOSeg is set to an AP IoU threshold of 0.5, and the auto-anchor has 1,000 evolutions of GE and 9 clusters of k-means. The weight of mask loss is set to 6 for the loss function. The optimizer has a momentum of 0.937, an initial learning rate of 0.01, a final learning rate of 0.1, and a decay rate of 0.0005. The DDPM has an input shape of 64 × 64 × 3 and generates pseudo images at 1.25 times the original number of images. Considering these configurations, YOLOSeg can be fine-tuned for specific tasks and datasets.

Image dataset

The image dataset of wafer die defects analyzed in this study is provided by a technology company in Taiwan. The original image size contains 1232 × 972 × 3 pixels. In this study, 549 defective images were collected as the dataset for training the model, which has been divided into 90% for training and 10% for validation. Besides the training image set, the study also used the validation image set to conduct sampling surveys and sensitivity experiments for the model. Another 275 defective images were used as a testing image set to evaluate the segmentation performance of the model.

The particle defects in semiconductor data have distinct characteristics that pose challenges for detection and segmentation. Firstly, the size and shape of these defects are generally very small, often constituting less than 0.02% of the entire image’s size. They typically appear as irregular dark spots on the wafer surface, though their shapes can vary. Secondly, the defects often exhibit low contrast against the wafer background, making them difficult to distinguish. The similar tones of the wafer surface and the defects create challenges for both manual annotation and automated detection processes. This low contrast necessitates advanced techniques for accurate defect identification and segmentation. The characteristics, small size and low contrast, are prevalent in wafer die defects, yet they present significant difficulties for existing segmentation methods, which often lack the precision required for accurate measurement. This dataset was chosen for its representative nature of common challenges in semiconductor defect inspection. By using this dataset, we aim to demonstrate and develop more effective techniques capable of overcoming these limitations, thereby advancing the accuracy and reliability of defect detection and segmentation in semiconductor manufacturing.

Figure 6 displays the ground-truth distribution in the training image set. Figure 6(a) shows the distribution of defect centroids, with x and y representing the coordinates of these centroids. In Fig. 6(a), except for the four pad areas, particle defects scattered at various positions within the wafer die image. There are many spot-like patterns on the pad area, and it is difficult for the human eye to distinguish them from the particle defects. Therefore, during annotation, we opted to exclude the pad areas from consideration to maintain annotation clarity and accuracy. Figure 6(b) is the scatter diagram representing the normalized size of the defects. It is evident that most defects are extremely small and their height and width constitute less than 0.02 of the entire image’s dimensions.

Model spot checking and designing rationale of YOLOSeg structure

On the basis of the object detection model, this study has developed an instance segmentation model for wafer die particle defects. As shown in Table 1, the mask R-CNN, the YOLACT, and the SOLO are chosen to conduct model spot checking, which is widely practiced nowadays. According to the experiment, AP and IoU of mask R-CNN can reach 0.747 and 0.597, respectively, which are approximately 13% and 7% higher than those of YOLACT. The AP and IoU of recently developed SOLO are merely 0.104 and 0.083, respectively. It means that SOLO exhibits very low prediction performance. Generally speaking, mask R-CNN is good but it takes 6,000 iterations to train a model, YOLACT is also good but its prediction performance is not as good as mask R-CNN, whereas SOLO struggles to detect small defects and is less suitable for this scenario.

The reason to resort to the instance segmentation is because it involves two fields: the object detection and the semantic segmentation model. In addition, we also acknowledge that there are models specifically designed for small object detection or segmentation in the two fields aforementioned. For this purpose, we endeavor to use three object detection models (Faster R-CNN, SSD and YOLOv5s) and three semantic segmentation models (FCN, SegNet and UNet) to perform model spot checking, so as to construct a prototype model suitable for the case in this study.

Let us refer to Table 1 again. Among the object detection models, Faster R-CNN, SSD and YOLOv5s are equal or better than mask R-CNN and YOLACT as far as AP is concerned. The AP of YOLOv5s even reaches 0.830, about 8.5% greater than that of Faster R-CNN and SSD, indicating that YOLOv5s has much better detection ability for small objects such as particle defects. Therefore, this study decided to select YOLOv5s as the detector of defect prediction boxes. In terms of semantic segmentation model, the IoU of UNet reaches 0.887, which means that its defect segmentation ability is much higher than that of mask R-CNN, YOLACT and SOLO, and is 64% greater than that of FCN and SegNet. Hence this study decided to select UNet as the segmenter of polygon boxes for defect prediction.

Based on the model spot-checking experiment, it was found that the existing instance segmentation models can perform to a certain extent in both small defect detection and small defect segmentation. However, the pure object detection model YOLOv5s performs better in small defect detection, while the pure semantic segmentation model UNet excels in small defect segmentation. The YOLOSeg proposed in this study is a combination of YOLOv5s and UNet, and this experiment may be regarded as the motif of the structural design of YOLOSeg.

Ablation studies

As one is undergoing the model training, the planned training tricks will exert influences upon the prediction performance of YOLOSeg. We initiate an ablation study to gradually increment model training tricks so as to explore the strength of each training trick’s contribution to the overall model. As shown in Table 2, this study selected Experiment A as the baseline. Experiment A trained the detection part and segmentation part for YOLOSeg at the same time; Experiment B was based on Experiment A and froze the detection part before it trained the segmentation part. Experiment C is based upon Experiment B. When Experiment C was training the segmentation part, its mask loss was switched from dice loss to bce-dice loss. Experiment D and Experiment E continued to put in mechanisms such as auto-anchor and DDPM image augmentation.

During the training, the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer with momentum is chosen and the one-cycler learning rate scheduler is used. The process of YOLO-based augmentation is also included. Experiments A and B show that if we train YOLOSeg with segmentation and detection tasks at once, predicting segmentation will have near zero performance compared with training detection first and train segmentation last while freezing detection part. This issue is possibly caused by the intrinsic property of segmentation and detection tasks, especially a small defect inspection problem. In Experiment A, a model has to learn both pixel level and bounding box level prediction, simultaneously. While in Experiment B, in the segmentation training process, the detection model part already possesses well-trained weight and bias for extracting useful information about defect location. With the aid of a detection model, the decoder can focus on how to transform feature maps from neck and backbone to prediction initial mask.

From Experiment B one knows that after freezing the detection part, the learning button of the segmentation part was pushed. Moreover, one sees from Experiment C that the most crucial training trick in this research is switching the mask loss of the segmentation part to bce-dice loss after the detection part was frozen. When the segmentation part gained the learning opportunity, dice loss continued to evaluate from a global perspective, while bce loss in a complementary fashion zooms in pixel by pixel from a microscopic perspective. The results of Experiment C show that when the AP rises slightly, there has been an explosive surge in the IoU.

This study also tried to switch dice loss towards focal loss, but the IoU could only reach 0.415, far lower than the performance of bce-dice loss, which was 0.715. The auto-anchor algorithm is found to be harmful for the AP about 3% but may increase IoU over 1% from the result of Experiment D for extremely small defects. The k-means and GE algorithm often offer small default anchor size which causes unstable gradient information flow or insufficient receptive field for prediction. Finally, Experiment E introduced the DDPM image augmentation to increase the quantity of training images and generate pseudo defects with rich appearances. With the help of this, it can be found a significant advantage in the improvement of the IoU. While AP bounces back slightly across experiments C, D, and E, the IoU increases from 0.715 in C to 0.754 in E. This indicates that DDPM augmentation significantly improves segmentation quality. Training with DDPM adds computational overhead, but this is balanced by a significant improvement in segmentation quality. The better segmentation accuracy justifies the extra training cost, making the trade-off worthwhile.

Die defect inspection performance of models

This experiment compared the prediction performance on the testing image set between state-of-the-art instance segmentation models and the proposed YOLOSeg. In particular, mask R-CNN2, YOLACT3, YUSEG5, and Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation were chosen but SOLO4 was excluded from the comparison due to its underwhelming performance during the model spot checking process in sub-Sect. “Model spot checking and designing rationale of YOLOSeg structure”. In addition, YUSEG can be regarded as a two-stage YOLOSeg where YOLO and UNet were trained separately. First, YOLO was used to detect the defects in the input image, and then cropped it into patches in accordance with the prediction boxes. Then, put the cropped patches into UNet for defect segmentation. Whereas the proposed YOLOSeg is an end-to-end model and thus can also be called the one-stage YOLOSeg. Besides, the primary difference between the proposed YOLOSeg and Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation lies in the segmentation head. YOLOSeg enhances the YOLOv5s model by integrating a UNet-like structure into the segmentation head.

Table 3 presents a comparison of different instance segmentation models in terms of number of model parameters in million, AP@IoU = 0.5, and IoU during testing stage. Mask R-CNN has the highest parameter count at 44 million, followed by YUSEG with 38.2 million and YOLACT with 31.2 million. Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation is much lighter with 7.6 million parameters. The YOLOSeg models include additional parameters for augmentation: YOLOSeg with DCGAN has 3.9 million for DCGAN and 7.15 million for YOLOSeg, totaling 11.05 million, while YOLOSeg with DDPM has 7 million for DDPM and 7.15 million for YOLOSeg, totaling 14.15 million. The additional parameters for DCGAN and DDPM do not affect inference directly. In terms of AP@IoU = 0.5, Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation leads with 0.872, showing strong detection capabilities. The YOLOSeg models also exhibit high AP, with 0.813 for DCGAN and 0.821 for DDPM, demonstrating effective detection. Mask R-CNN and YUSEG have comparable AP values of 0.745 and 0.743, respectively, while YOLACT has the lowest AP at 0.592. The IoU shows that YOLOSeg with DDPM achieves the highest IoU of 0.732, indicating superior segmentation performance. YOLOSeg with DCGAN also shows a high IoU of 0.722. Mask R-CNN provides a decent IoU of 0.594, better than YUSEG at 0.576 and YOLACT at 0.528. Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation has the lowest IoU at 0.433, despite its high AP. There is a trade-off between AP and IoU. Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation excels in AP, making it suitable for tasks prioritizing detection speed and efficiency, but its low IoU indicates less precise segmentation. In contrast, the proposed YOLOSeg models, especially with DDPM, balance high AP with significantly better IoU, making them ideal for applications requiring precise segmentation.

Figure 7 shows the qualitative prediction results of different instance segmentation models. Due to the signed non-disclosure agreement and the overlapping prediction results, we reproduced, sliced and discolored the prediction results of each model. Figure 7 shows that the proposed YOLOSeg is superior to the other instance segmentation models in terms of defect detection and segmentation. YOLOSeg has significantly fewer missing boxes, and the mask edge is closer to the defect contour.

Figure 8 illustrates two failure cases of the proposed YOLOSeg model. Comparing with Figs. 8(a3) and (b3), Figs. 8(a1)-(b2) show the detection and segmentation results where only a portion of the defects is identified. The model’s failure to detect all defects may be due to the subtle appearance of defects and their low contrast against the background. These reasons make it difficult to accurately detect and segment all defect areas.

Effects of DDPM image augmentation on prediction performance

The DDPM-based image augmentation method inputs the real particle defective patches. After adversarial learning, pseudo particle patches are generated and pasted randomly on the defect-free die images. Thereafter pseudo defective images can be generated, as Fig. 9 has presented below.

This study resorted to generating different numbers of pseudo defective images by virtues of DDPM and DCGAN, then augmented the training image set to 1 (the baseline), 1 and ¼, 1 and ½, 1 and ¾, and 2 times, respectively. After the images have been trained with the YOLOSeg, we continued to record the AP and the IoU trajectories of the training image set and the testing image set, as exhibited in Fig. 10. The AP of the training image set first rose slightly and then plunged sharply, while the IoU dropped dramatically first and then slightly went down. The AP and IoU of the testing image set are not only less than those of the training image set, but also show a decreasing trend. Overall, the best performance was recorded at the time when the pseudo image has been augmented to 1 and ¼ times. From this experiment, we have seen that particle defects generated by the DDPM and DCGAN can be naturally embedded on the wafer die image in different shapes, sizes, and numbers. This experiment increases the number of training images and diversifies the defects. More than that, YOLOSeg has the opportunity to learn richer appearances of the defect, eventually being a role to leverage the prediction performance of YOLOSeg.

Conclusion

Defective image collection, defect annotation, and feature engineering description are the most time-consuming tasks of defect inspection. The YOLOSeg proposed in this study effectively overcome these challenges step by step with DDPM generative pseudo defective images, DIP of auto-annotating pseudo defects, and fully convolutional automatic feature learning. Regardless of the variability in die patterns, adopting YOLOSeg, eliminates the need to collect a large number of defective samples, annotate numerous of defects, or rely heavily on feature engineering. Users only needs to prepare a few defective images with corresponding manual annotations. These can be adapted using the frozen layer, loss function conversion, auto-anchor, and the DDPM image augmentation to train YOLOSeg. After that, YOLOSeg is capable of predicting shapes, coordinates, and confidences of the defects. The conducted experiments show that YOLOSeg outperforms other current state-of-the-art models (AP reaching 0.821 and IoU reaching 0.732) including mask R-CNN, YOLACT, YUSEG, and Ultralytics’s YOLOv5s-segmentation in the field of instance segmentation. These results endorse the applicability of YOLOSeg in the detecting and segmenting defects as small as the particles on the wafer die. YOLOSeg is potentially helpful for the defect detection and segmentation that has to deal with various kinds of wafer die patterns.

Each pixel in die images corresponds to 3.36 μm. The proposed method achieved an IoU score of 0.732 which means that 73.2% of the segmented area accurately overlaps with the ground truth. Consequently, the discrepancy from the ground truth is 26.8%. Although the proposed method represented a 20–30% improvement of IoU over state-of-the-arts, there is room for enhancement, especially given the stringent nano-scale precision requirements in semiconductor manufacturing. Future research should focus on further refining the segmentation algorithms to reduce the error margin.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions from the anonymous semiconductor company in Taiwan but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

K. He, G. Gkioxari, P. Dollár, and R. Girshick. Mask r-cnn, in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 2017, pp. 2961–2969 (2017).

D. Bolya, C. Zhou, F. Xiao, and Y. J. Lee. Yolact: Real-time instance segmentation, in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Korea, 9157–9166 (2019).

X. Wang, T. Kong, C. Shen, Y. Jiang, and L. Li. Solo: Segmenting objects by locations, in Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 649–665 (2020)

B. Bai, J. Tian, and T. Wang. YUSEG: Yolo and Unet for cell instance segmentation is all you need, in 36th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, United States (2022).

A. Dutta and S. Biswas. Cnn based extraction of panels/characters from bengali comic book page images, in 2019 International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition Workshops (ICDARW) (Vol. 1, pp. 38–43). IEEE, (2019).

Y. G. Kim, D. U. Lim, J. H. Ryu, and T. H. Park. SMD defect classification by convolution neural network and PCB image transform, in 2018 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Computing, Communication and Security, Kathmandu, Nepal, 180–183 (2018).

Cheon, S., Lee, H., Kim, C. O. & Lee, S. H. Convolutional neural network for wafer surface defect classification and the detection of unknown defect class. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 32(2), 163–170 (2019).

Chen, X. et al. A light-weighted cnn model for wafer structural defect detection. IEEE Access 8, 24006–24018 (2020).

Ahmadi, B., Heredia, R., Shahbazmohamadi, S. & Shahbazi, Z. Non-destructive automatic die-level defect detection of counterfeit microelectronics using machine vision. Microelectron. Reliab. 114, 113893 (2020).

Chen, S. H., Kang, C. H. & Perng, D. B. Detecting and measuring defects in wafer die using gan and yolov3. Appl. Sci. 10(23), 8725 (2020).

Chen, S. H. & Tsai, C. C. SMD LED chips defect detection using a YOLOv3-dense model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 47, 101255 (2021).

Wen, G., Gao, Z., Cai, Q., Wang, Y. & Mei, S. A novel method based on deep convolutional neural networks for wafer semiconductor surface defect inspection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 69(12), 9668–9680 (2020).

Tao, X., Ma, W., Lu, Z. & Hou, Z. Conductive particle detection for chip on glass using convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 3519310 (2021).

Nakazawa, T. & Kulkarni, D. V. Anomaly detection and segmentation for wafer defect patterns using deep convolutional encoder–decoder neural network architectures in semiconductor manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manufact. 32(2), 250–256 (2019).

Chiu, M. C. & Chen, T. M. Applying data augmentation and mask R-CNN-based instance segmentation method for mixed-type wafer maps defect patterns classification. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manufact. 34(4), 455–463 (2021).

Nag, S., Makwana, D., Mittal, S. & Mohan, C. K. WaferSegClassNet-A light-weight network for classification and segmentation of semiconductor wafer defects. Comput. Ind. 142, 103720 (2022).

T. H. Wong, “Die defect detection for integrated circuit using deep learning object detection techniques,” Doctoral dissertation, UTAR (2023).

I. Goodfellow, J. Pouget-Abadie, M. Mirza, B. Xu, D. Warde-Farley, S. Ozair, A. Courville, and Y. Bengio, “Generative adversarial nets,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 27, (2014).

D. M. Tsai, M. S. Fan, Y. Q. Huang, and W. Y. Chiu, “Saw-mark defect detection in heterogeneous solar wafer images using GAN-based training samples generation and CNN classification,” In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on Computer Vision, Imaging and Computer Graphics Theory and Applications, Prague, Czech Republic, pp. 234–240 (2019).

V. De Ridder, B. Dey, S. Halder, and B. Van Waeyenberge, “SEMI-DiffusionInst: A diffusion model based approach for semiconductor defect classification and segmentation,” in 2023 International Symposium ELMAR, pp. 61–66. IEEE, (2023).

Wijaya, A., Wagner, J., Sartory, B. & Brunner, R. Analyzing microstructure relationships in porous copper using a multi-method machine learning-based approach. Commun. Mater. 5(1), 59 (2024).

Tang, S. et al. A timestep-adaptive-diffusion-model-oriented unsupervised detection method for fabric surface defects. Processes 11(9), 2615 (2023).

Dutta, A., Garai, A., Biswas, S. & Das, A. K. Segmentation of text lines using multi-scale CNN from warped printed and handwritten document images. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recognit. 24(4), 299–313 (2021).

Casas, E., Ramos, L., Romero, C. & Rivas-Echeverría, F. A comparative study of YOLOv5 and YOLOv8 for corrosion segmentation tasks in metal surfaces. Array 22, 100351 (2024).

Yang, C. H., Ren, J. H., Huang, H. C., Chuang, L. Y. & Chang, P. Y. Deep hybrid convolutional neural network for segmentation of melanoma skin lesion. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021, 9409508 (2021).

F. Milletari, N. Navab, and S. A. Ahmadi, “V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation,” in 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision, (Stanford, California, USA, 2016) 565–571.

Taghanaki, S. A. et al. Combo loss: Handling input and output imbalance in multi-organ segmentation. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 75, 24–33 (2019).

Funding

National Science and Technology Council, 113-2221-E-131-031.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ssu-Han Chen wrote the main manuscript text and did main experiment. Yen-Ting Li, Yu-Cheng Chan, Chen-Che Huang, and Yu-Chang Hsu prepared method, coding, and did experiment. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Declarations

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, YT., Chan, YC., Huang, CC. et al. YOLOSeg with applications to wafer die particle defect segmentation. Sci Rep 15, 2311 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86323-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86323-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Hybrid Wafer Defect Detection and Segmentation Using Verilog-Based Image Preprocessing and Deep Learning Architectures

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)