Abstract

Previous research focused primarily on static metabolic syndrome (MetS) status, with less discussion on the effects of its dynamic changes on cardiovascular diseases (CVD), stroke, and all-cause mortality. This study examines the impact of MetS status changes on these health outcomes. This study used data from two prospective cohorts: the China Longitudinal Study of Health and Retirement (CHARLS) and the Wuhan Elderly Health Examination Center community (WEHECC). MetS was determined using the ATP III criteria. Participants were classified based on changes in MetS status, defined as MetS-free, MetS-recovery, MetS-developed, and MetS-chronic, assessed at baseline and at follow-up (three years later for CHARLS and six years later for WEHECC cohort). The primary outcomes for CHARLS included all-cause mortality, physician-diagnosed CVD, and stroke, while WEHECC cohort focused solely on all-cause mortality. Logistic regression models were utilized to calculate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Over the follow-up period from 2015 to 2018 in CHARLS, 335 participants (7.1%) developed CVD, and 237 (5.1%) experienced a stroke. Relative to the MetS-free group, individuals with MetS-chronic displayed higher risks of CVD (OR, 1.63 [95% CI, 1.25 to 2.13]) and stroke (OR, 2.95 [95% CI, 2.11 to 4.15]). In the WEHECC cohort, 40 participants died by 2022, with the MetS-chronic group showing a increased risk of all-cause mortality (OR, 2.76 [CI, 1.03 to 7.39]). Changes in MetS status are associated with different risks of CVD, stroke, and mortality, with chronic MetS significantly increasing these risks compared to MetS-free.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) encompasses a constellation of metabolic irregularities, including visceral obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia1. The presence of MetS heightens the susceptibility to cardiovascular events and amplifies the risk of all-cause mortality2,3,4. With the ongoing global surge in obesity-related health issues5, the prevalence of MetS is expected to escalate6, consequently intensifying the economic and healthcare burden link to it7,8.

Several prior studies have demonstrated a substantial association between MetS and an elevated risk of both all-cause mortality and mortality due to cardiovascular disease (CVD)9,10. Previous studies primarily investigated the relationships between the baseline MetS status and the incidence of adverse long-term outcomes. However, MetS represents a condition that assesses metabolic irregularities rather than being categorized as a distinct disease, since it can undergo changes with lifestyle modifications and is reversible6. Despite this potential for change, the benefits of actively managing and improving MetS outcomes remain uncertain, as previous studies have reported mixed results, with some showing significant reductions in adverse outcomes11,12 and others finding little to no long-term impact13. This uncertainty underscores the need for our study, which aims to investigate the effects of dynamic changes in MetS status. Limited research has been conducted to explore the influence of alterations in MetS status on the incidence of CVD11,12,13. A Korean cohort study observed that recovery from MetS was associated with a decreased risk of CVD events12, whereas the emergence of new MetS increased this risk. There was only a single study conducted on the mainland Chinese population13, utilizing the Kailuan cohort from Hebei province. However, this study focused on a specific occupational group of workers, leaving a notable gap in evidence the middle-aged and elderly population.

This study employed data from two prospective cohorts: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) and the Wuhan Elderly Health Examination Center community (WEHECC). The aim was to assess the association between changes in MetS status over time all-cause mortality as well as the incidence of CVD within a large sample of middle-aged and elderly individuals in mainland China (CHARLS) and a community-dwelling elderly population in Wuhan (WEHECC).

Methods

Study design and population

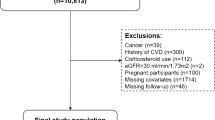

The CHARLS14, initiated in 2011, is an ongoing national longitudinal survey collecting vital health and retirement data from individuals aged 45 years and older in China. The dataset, publicly available at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/index/zh-cn.html, provides detailed information on its sampling design and cohort profile, ensuring a nationally representative sample. The survey employs rigorous one-on-one interviews with a structured questionnaire, ensuring high-quality and reliable data for comprehensive analysis. In this study, we employed data from the CHARLS 2011 and 2015 to ascertain the alterations in MetS status and conducted a follow-up assessment using CHARLS 2018. Detailed information of this study design was presented in Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study population selection for CHARLS and WEHECC. CHARLS, China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study; WEHECC, Wuhan Elderly Health Examination Center community; MetS, metabolic syndrome; MetS- = metabolic syndrome free status; MetS + = metabolic syndrome present status; BMI, body mass index.

Sensitivity analysis for the association between changes in MetS status and risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke

To validated our findings, we conducted a series of Sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis 1 incorporated the 2020 data, and while the overall findings remained consistent with those in Table 1, the MetS-recovery group exhibited a significant association with CVD outcomes (Table S6).

In Sensitivity analysis 2, after excluding the current or former smoker, consistent results were found with the original analyses. Different incidence rates and risks of CVD, stroke and all-cause mortality were observed among different dynamic patterns of MetS (Table S7).

In Sensitivity analysis 3, in Cox mixed-effects models, employing the province of origin of participants as a random effect, the obtained results were consistent with the original findings on the basis of Model 3 in Table 1 (Table S8).

Sensitivity analysis 4 suggested that the inclusion of weekly exercise volume as a covariate produced results consistent with the original findings on the basis of Model 3 in Table 1. For more detailed information, refer to Table S9.

This study included 6315 participants with identifiable MetS statuses at two time points in 2011 and 2015 (Fig. 1). Among the 6315 eligible participants, 1583 participants were excluded based on the follow exclusion criteria: (1) individual under age 45 years; (2) participants with a personal history of CVD and stroke at baseline, where CVD includes heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems; (3) participants who already had cancer at baseline; (4) individuals whose body mass index (BMI) remained at or below 18.5 in the second investigation periods. The final analysis included a total of 4707 participants, comprising 2073 in MetS-free group, 526 in MetS-developed group, 725 in MetS-recovery group and 1383 in MetS-chronic group.

In addition to the primary cohort (CHARLS), we included data from the Wuhan Elderly Health Examination Center community (WEHECC) to enhance the robustness and generalizability of our findings. CHARLS provides a nationally representative cohort of middle-aged and elderly individuals across China, while WEHECC allows us to examine a specific community-dwelling elderly population in Wuhan. By using data from both cohorts independently, we mitigate the potential biases that may arise from relying on a single dataset. This approach strengthens the external validity of our study and allows for a more comprehensive analysis by incorporating both national and regional perspectives, ultimately providing a more reliable and balanced understanding of the relationship between metabolic syndrome and health outcomes. This dataset included individuals aged 65 and above who underwent health examinations in 2014 and 2016, with follow-up on mortality outcomes until 2022, providing a follow-up duration of approximately 6 years. Initially, 851 individuals who participated in the 2014 survey were included. After excluding 492 participants who did not participate in the 2016 follow-up and 5 individuals with missing MetS definition data, a final cohort of 354 participants was included in the analysis. The specific participant selection process is presented in Fig. 1. Ethical approval for WEHECC was granted by the Wuhan University School of Medicine.

Exposure variables

In accordance with the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) criteria15, MetS was defined by the presence of a minimum of three out of the following five risk factors: (a) central obesity (waist circumference ≥ 85 cm in Asian men and ≥ 80 cm in Asian women); (b) low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C; fasting HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women); (c) elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg, or antihypertensive drug treatment in a patient with a history of hypertension); (d) hypertriglyceridemia (fasting plasma triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL or drug treatment for elevated triglycerides); and (e) hyperglycemia (fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or drug treatment for elevated glucose).

Fasting blood samples were collected and stored at the Chinese CDC. Biomarkers like HDL, triglycerides, and fasting glucose were assessed at the Younanmen Center of Capital Medical University. Trained nurses measured blood pressure three times with participants seated, using the average as the final result. Waist circumference was measured with participants standing, using a ruler at navel level after exhalation.

The participants were categorized into four distinct groups based on predefined criteria: MetS-free group (those who were free of MetS at both 2011 and 2015); MetS-developed group (those who did not have MetS at 2011 but developed during follow-up); MetS-recovery group (those who had MetS at 2011 but were MetS free at 2015), and MetS-chronic group (those with MetS at both 2011 and 2015). The alterations in the status of the individual components of MetS were also classified into four groups: free, developed, recovery, chronic.

Outcome variables

The study examined outcomes including all-cause mortality, CVD, and stroke, using data from CHARLS. CVD events were identified through participant responses to questions about doctor-diagnosed heart conditions or stroke. CVD included heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems. Participants reporting these were classified as having CVD or stroke. All-cause mortality was tracked from 2015 to 2018, with CHARLS using informant interviews to document deaths.

Covariates

Several covariates were controlled in the study, including age, sex, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, working status, marital status, residence and disease history. Education level was categorized as high school or higher and middle school or less. Smoking status included never and current/former smoker. Alcohol consumption was categorized as none and current/former consumption. Work status was classified into 4 groups, including only agricultural work, only non-agricultural work, both agricultural and non-agricultural work and not work. Marital status was categorized as married/cohabiting, never married and other. Residence was sorted as village and other. Disease history included 8 diseases based on CHARLS involved: chronic lung disease, liver disease, kidney disease, stomach or other digestive disease, emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, memory-related disease, arthritis or rheumatism and asthma. Disease history in the baseline table was represented as a continuous variable, indicating the number of coexisting diseases.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were described by MetS status, with continuous variables as means (SDs) and categorical variables as numbers (percentages). ANOVA was used for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical ones. Logistic regression models were employed to calculate the odd ratio (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Models were adjusted as follows: Model 1; Model 2, adjusted for age and sex; Model 3, adjusted for age, sex, education level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, work, marital status, residence, disease history. A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted, including the following methodologies and approaches: (1) Analysis Including 2020 Data (Wave 5). (2) Excluding smokers and adjusting covariates. (3) Using fully adjusted mixed-effects Cox regression with province as a random effect. (4) On top of the existing Model 3, the covariate of weekly exercise duration was added to account for the influence of physical activity. Physical exercise lasting a minimum of 10 min per week was classified into three categories based on intensity: vigorous activities, moderate activities, and light activities.

For the WEHECC dataset, the same statistical methods were applied as described above. The analyses were adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, alcohol consumption, marital status, and education.

We addressed missing values for covariates using multiple imputations by chained equations (MICE). To ensure the robustness of our findings, we repeated the analyses using the non-imputed dataset, and the results were consistent with those from the imputed datasets. R version 4.2.2 was conducted for all statistical analysis in this study and 2-sided P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. To maintain consistency and clarity, all P-values are now reported to three decimal places, with P < .001 used to indicate values below this threshold.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the subject

In the CHARLS cohort analysis, among the 4707 eligible subjects at baseline, the mean age was 62.1 (± 8.58) years and 2514 (53.1%) were female. According to the definition of changes in MetS status, all participants were classified into four groups including MetS-free (n = 2073), MetS-recovery (n = 725), MetS-developed (n = 526) and MetS-chronic(n = 1383). A comprehensive summary of the baseline characteristics of the subjects categorized according to the dynamic patterns of MetS was presented in Table S1. It was observed that both the MetS-free and MetS-recovery groups exhibited the lowest proportions of individuals who did not engage in regular exercise compared to all other analyzed groups. In the investigated subgroups with younger mean ages, alcohol consumption and smoking were found to be more prevalent. In the comparison of comorbidity counts, it can be observed that participants diagnosed with MetS in 2011 had a higher number of comorbidities at baseline. The MetS-chronic group showed the highest percentages of hypertension (41.6%), diabetes (11.0%), hyperlipidemia (16.1%), and the highest means of BMI (26.3 ± 7 kg/m2), SBP (138 ± 19.4mmHg), DBP (79.7 ± 11.6 mmHg), WC (92.5 ± 9.92 cm), FPG (119 ± 45.9 mg/dL), TG (211 ± 111 mg/dL), and the lowest mean of HDL (45.6 ± 9.22 mg/dL), in the comparison of four groups. Furthermore, MetS components refer to the number of criteria met according to the ATP III diagnostic criteria. The baseline table presented the number of criteria met for the diagnosis of MetS among the participants, based on the diagnostic criteria of ATP III in 2011 and 2015. Individuals belonging to the MetS-chronic group exhibited a higher frequency of having 5 MetS components at baseline (2015) or in the prior examination (2011) compared to individuals in the remaining groups.

In the WEHECC cohort, the MetS-free (n = 142), MetS-recovery (n = 12), MetS-developed (n = 108), and MetS-chronic (n = 92) groups were analyzed. The MetS-Chronic group exhibited the highest levels across several key indicators compared to the other groups. This group had the highest mean weight (65.5 kg), BMI (25.3 kg/m²), and waist circumference (86.8 cm), along with the highest prevalence of hypertension (80.4%), diabetes (42.4%), and dyslipidemia (97.8%). Additionally, the MetS-Chronic group had the most unfavorable metabolic profiles, with the highest fasting glucose (6.99 mmol/L) and triglycerides (2.32 mmol/L), and the lowest HDL-cholesterol (1.12 mmol/L). These findings highlight the significant metabolic and health burden in individuals with chronic MetS. Detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Table S2.

The risk for all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke incidence according to the dynamic MetS status

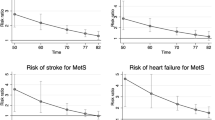

During follow-up period, 335 (7.1%) participants developed CVD, 237 (5.1%) participants developed stroke in 4707 participants in the longitudinal cohort. The overall effects of dynamic MetS status on CVD, stroke and all-cause mortality are comprehensive summarized in Table 1. On adjusted multivariable analysis model 3, compared with the Met-free group, MetS-chronic increased the risk of CVD (adjusted OR, 1.63 [CI, 1.25 to 2.13]), in Fig. 2. The MetS-chronic group had the highest risk of stroke (adjusted OR, 2.95 [CI, 2.11 to 4.15]), followed by the MetS-developed (adjusted OR, 2.22 [CI, 1.42 to 3.49]), and the MetS-recovery (adjusted OR, 2.08 [CI, 1.38 to 3.14]). The heightened risk observed across all change of MetS status did not reach statistical significance concerning all-cause mortality.

We supplemented our study with community data sourced from the WEHECC. The population consisted of individuals aged 65 and above. We utilized data from 2014 and 2016 to define the changes in the status of MetS and followed up on mortality outcomes until 2022. The cohort comprised 354 individuals, among whom 40 participants died during the follow-up period. On adjusted multivariable analysis model, compared with the Met-free group, MetS-chronic increased the risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted OR, 2.76 [CI, 1.03 to 7.39]) , as shown in Fig. 2.

Risk for all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke incidence according to the dynamic MetS status. CHARLS, China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study; WEHECC, Wuhan Elderly Health Examination Center community; MetS, metabolic syndrome; OR, odd ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular diseases. Adjusted for age; sex; education; smoking status; alcohol consumption; work; marital status; residence; disease history (chronic lung disease, liver disease, kidney disease, stomach or other digestive disease, emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, memory-related disease). *P values < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

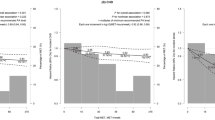

Age differences in changes in MetS status and risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke

To investigate the impact of age at which MetS developed on the risk of CVD, stroke, and all-cause mortality, the study stratified participants into two age groups: those below 65 years and those aged 65 years and above. The analysis revealed significant risk differences for CVD, stroke, and all-cause mortality between these distinct age groups (Fig. 3). Compared with the MetS-free group within the corresponding age bracket, MetS-chronic group (<65 years) exhibited higher risks of CVD (adjusted OR, 1.69 [CI, 1.19 to 2.38]), while MetS-chronic group (≥ 65 years) had higher risks of stroke (adjusted OR, 3.28 [CI, 1.91 to 5.62]).

Risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke incidence according to the age of MetS status change. MetS, metabolic syndrome; OR, odd ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular diseases. Adjusted for age; sex; education; smoking status; alcohol consumption; work; marital status; residence; disease history (chronic lung disease, liver disease, kidney disease, stomach or other digestive disease, emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, memory-related disease). *P values < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

Sex differences in changes in MetS status and risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke

The analysis unveiled disparities in risk for CVD, stroke, and all-cause mortality across distinct sex groups (Fig. 4). Compared the Mets-free group, Mets-chronic group was associated with a significant elevated risk on CVD in both males and females, while males were more vulnerable to Mets-associated CVD, with the ORs of 1.57 [CI, 1.12 to 2.22] for females and 1.88 [CI, 1.21 to 2.91] for males. The occurrence of Mets was significantly associated with stroke outcomes in females, while in males, a significant association was observed only with MetS-chronic group. In both sex, the MetS-chronic group had the highest risk of stroke, with the ORs of 3.62 [CI, 2.08 to 6.29] for female and 2.70 [CI, 1.71 to 4.25] for male, compared with the MetS-free group.

Risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke incidence according to the sex of MetS status change. MetS, metabolic syndrome; OR, odd ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular diseases. Adjusted for age; education; smoking status; alcohol consumption; work; marital status; residence; disease history (chronic lung disease, liver disease, kidney disease, stomach or other digestive disease, emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, memory-related disease). *P values < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered statistically significant.

Changes in MetS and its components and the risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke

The association between the MetS components and the risk of all-cause mortality, CVD and stroke is reported in Supplementary Table S3 to S5. After adjustment for confounding factors, the associations remained statistically significant for the persistent status of high WC and the development and persistence of high BP concerning both CVD and stroke outcomes. The following factors was associated with an increased risk of CVD: persistence of high WC (adjusted OR, 1.48 [CI, 1.07 to 2.05]), development of high BP (adjusted OR, 2.00 [CI, 1.39 to 2.87]) and persistence of high BP (adjusted OR, 1.79 [CI, 1.34 to 2.41]), in Model 3 of Supplementary Table S4. The following factors were found to be associated with an elevated risk of stroke: persistence of high WC (adjusted OR, 1.62 [CI, 1.10 to 2.38]), development of high BP (adjusted OR, 2.34 [CI, 1.45 to 3.80]), persistence of high BP (adjusted OR, 2.85 [CI, 1.95 to 4.18]) and persistence of low HDL (adjusted OR, 2.07 [CI, 1.45 to 2.97]), in model 3 (Table S5).

Discussion

This prospective cohort study demonstrates that dynamic changes in MetS significantly influence the risks of all-cause mortality, CVD, and stroke. Individuals with chronic MetS are at a higher risk for CVD and stroke compared to MetS-free individuals. Early onset of MetS further elevates the risk of CVD. For gender, females showed a higher stroke risk than males in the MetS-chronic group. Interestingly, no increased risk of CVD or all-cause mortality was found in the MetS-recovery group, indicating that MetS does not inevitably lead to adverse outcomes. These findings underscore the importance of early and sustained interventions to mitigate the risks associated with MetS.

Our study, which included participants from 28 provinces of China using the CHARLS questionnaire, offers a more comprehensive analysis compared to previous cohort studies limited by population scope13, lack of mortality data12, or regional focus11. While previous studies have established that MetS increases the risk of all-cause mortality and CVD9,10,16, they often based their findings on baseline MetS status. Our study emphasizes the need to consider the dynamic nature of MetS during follow-up to better understand its impact on health outcomes.

Chronic MetS was associated with a significantly higher CVD risk compared to the MetS-free group, whereas the MetS-recovery and MetS-developed groups showed a non-significant risk. This suggests that prolonged MetS is necessary for CVD development17,18. In contrast, the risk of stroke remained significant across all MetS groups, indicating that even those who recover from MetS may still face an elevated stroke risk19,20. The absence of significant effects on all-cause mortality might be due to the study’s follow-up period not being long enough. In our supplemented community cohort, the follow-up for mortality outcomes extended until 2022, allowing us to observe a significant effect of MetS-chronic group on died outcomes. Thus, we can infer that prolonged Mets status may increase the risk of all-cause mortality.

These findings highlight the critical need for transitioning individuals from a MetS to a non-MetS state to reduce adverse outcomes. Effective monitoring and management of key metabolic indices—waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting glucose, and lipid levels—are essential in reducing CVD and stroke risks9,10,16. Interventions such as lifestyle modifications (e.g., diet, exercise, smoking cessation) and dynamic medication adjustments are crucial21. Regular follow-ups combining lifestyle and medication strategies can optimize long-term health and quality of life, underscoring the importance of proactive health management.

Our study identified that the age at which MetS status changed was correlated with the risks of CVD and stroke. The slightly higher mean age observed in the MetS-Recovery and MetS-Chronic groups suggests that older individuals are either more susceptible to developing chronic MetS, while early onset of MetS is associated with higher CVD risk. Unhealthy lifestyle factors, such as smoking, lack of exercise, and poor weight control, significantly contribute to MetS risk22. Those with early MetS development likely experienced more unhealthy lifestyles, leading to obesity, metabolic issues, and long-term adverse outcomes23. Individuals aged over 65 have a higher risk of stroke. Stroke was mainly caused by the atherosclerosis, and MetS was considered as an important risk factor for developing atherosclerosis24. As age increases, there is a gradual decline in the elasticity of blood vessels, rendering them more vulnerable and prone to atherosclerosis. This vascular remodeling can lead to plaque buildup on blood vessel linings, increasing stroke risk25. These findings highlight the importance of preventive health strategies to reduce MetS risk and emphasize proactive management and interventions for those already diagnosed to reverse the syndrome and minimize adverse outcomes.

Metabolic syndrome increases stroke risk more in women than men. A large study in northern Manhattan found that, even after adjusting for factors like smoking, alcohol use, and inactivity, women with MetS had a higher stroke risk than men26. Several previous studies had reached the same conclusion19,27. The most common biological explanation for sex differences in stroke is related to sex steroid hormones, particularly estrogen28. In premenopausal women, elevated oestradiol enhances vascular health and protects against stroke by improving endothelial function and lipid profiles. However, this protection diminishes during the transition to postmenopause, increasing stroke risk29. Diabetes, hypertension and elevated BMI are more strongly associated with incident stroke in female compared with male30. Females are more prevalent in MetS-recovery, MetS-developed, and MetS-chronic groups, while males dominate the MetS-free group. This highlights the need for focused MetS prevention and health management in women to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes like stroke.

The study further showed that alterations in some MetS components altered risks for CVD and stroke. For example, persistent status of high WC, the development of high BP and persistence of high BP associated with higher risk of CVD and stroke, compared with remaining free of these components31,32. The higher risk of stroke also related to persistence of low HDL. Previous studies have also shown that higher BP and WC were strongly associated to CVD and stroke33,34. Greater focus should be placed on monitoring BP and WC, key components of MetS, to prevent CVD and stroke. Baseline data shows that individuals in the MetS-developed Group have elevated waist circumference, BP, triglycerides, and fasting glucose, along with lower HDL, indicating higher metabolic risk. The MetS-Recovery Group, despite improvements, still shows abnormalities in WC and HDL, requiring ongoing management. Components like waist circumference, HDL, BP, glucose, and triglycerides respond well to lifestyle changes, including diet, exercise, and medication adherence35, which are vital for reducing MetS risks and preventing its progression to CVD and stroke.

In the sensitivity analysis that included data from 2020, although we anticipated that individuals who transitioned to the MetS-recovery group would experience better outcomes, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic may have introduced important confounding effects. In our study, we observed that improvements in the recovery group were particularly evident in glycemic control, along with reductions in waist circumference and other relevant MetS-related markers. However, prior research has shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection can exacerbate hyperglycemia through pancreatic β-cell impairment, and the use of glucocorticoids in severe COVID-19 cases can further raise blood glucose levels36,37. Additionally, older adults—who comprise a substantial portion of the CHARLS cohort—are at an elevated risk of muscle mass loss, particularly in the context of reduced physical activity during the pandemic38. Thus, although waist circumference reduction often indicates metabolic improvement, it may also reflect a decline in muscle mass and the potential development of sarcopenia in this setting. Prolonged inflammation and other pandemic-related stressors could therefore attenuate or negate the anticipated benefits of MetS recovery, ultimately affecting cardiovascular outcomes in this population.

Our study has limitations. First, the follow-up of this study is relatively short, short follow-up could not evaluate of long-term effects of the changes of MetS status. We recommend extending follow-up in future studies to at least 10 years to more comprehensively assess the impact of MetS on health outcomes over time. Second, individuals at baseline may have had prior long-term exposure to metabolic syndrome, therefore, there is a possibility of misestimating the effects of MetS-recovery and MetS-chronic on all-cause mortality, CVD, and stroke. Third, a limitation of the CHARLS dataset is the potential underreporting of conditions like hypertension and diabetes39 However, the use of objective measurements for fasting glucose and blood pressure mitigates this issue for MetS classification. Additionally, the likelihood of underreporting for CVD and stroke is low, as these conditions typically require medical attention, making self-reports more reliable. Fourth, since this cohort consists of middle-aged and older individuals living in mainland China, the results may not be the same in other populations. Furthermore, the ATP III criteria do not serve as the sole standardized definition for metabolic syndrome. Additionally, while we used the ATP III criteria, which are widely recognized and validated for defining metabolic syndrome, they treat all components equally and do not account for the potentially disproportionate impact of specific components, such as triglycerides and fasting glucose, on overall MetS status. Finally, our data did not include assessments of the severity of CVD and stroke.

Conclusion

Dynamic changes in MetS increase the risks of CVD and stroke, especially in females and with early onset. The implications of our findings underscore the significance of monitoring dynamic changes in MetS for effective prevention and control of CVD and stroke.

Data availability

Datasets were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2011-2018 (available at https://charls.pku.edu.cn/).

References

Alberti, K. G. M. M., Zimmet, P. & Shaw, J. The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet 366, 1059–1062 (2005).

Hunt, K. J., Resendez, R. G., Williams, K., Haffner, S. M. & Stern, M. P. National cholesterol education program versus world health organization metabolic syndrome in relation to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the San Antonio heart study. Circulation 110, 1251–1257 (2004).

Wilson, P. W. F., D’Agostino, R. B., Parise, H., Sullivan, L. & Meigs, J. B. Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 112, 3066–3072 (2005).

Silveira Rossi, J. L. et al. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases: going beyond traditional risk factors. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 38, e3502 (2022).

Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15, 288–298 (2019).

Saklayen, M. G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 20, 12 (2018).

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27 (2017).

Wang, Y., Wang, L. & Qu, W. New national data show alarming increase in obesity and noncommunicable chronic diseases in China. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 71, 149–150 (2017).

Amouzegar, A., Mehran, L., Hasheminia, M., Kheirkhah Rahimabad, P. & Azizi, F. The predictive value of metabolic syndrome for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 33, e2819 (2017).

Guembe, M. J., Fernandez-Lazaro, C. I., Sayon-Orea, C., Toledo, E. & Moreno-Iribas, C. Risk for cardiovascular disease associated with metabolic syndrome and its components: a 13-year prospective study in the Rivana cohort. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19, 195 (2020).

Lai, Y. et al. Modification of the all-cause and cardiovascular disease related mortality risk with changes in the metabolic syndrome status: a population-based prospective cohort study in Taiwan. Diabetes Metab. 49, 101415 (2023).

Park, S. et al. Altered risk for cardiovascular events with changes in the metabolic syndrome status: a nationwide population-based study of approximately 10 million persons. Ann. Intern. Med. 171, 875–884 (2019).

He, D. et al. Dynamic changes of metabolic syndrome alter the risks of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: evidence from a prospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 706999 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68 (2014).

Alberti, K. G. M. M. et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120, 1640–1645 (2009).

Sundström, J. et al. Clinical value of the metabolic syndrome for long term prediction of total and cardiovascular mortality: prospective, population based cohort study. BMJ 332, 878–882 (2006).

Wang, J. et al. The metabolic syndrome predicts cardiovascular mortality: a 13-year follow-up study in elderly non-diabetic Finns. Eur. Heart J. 28, 857–864 (2007).

He, S. et al. Long-term influence of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome on all-cause and cardiovascular death, and microvascular and macrovascular complications in Chinese adults—a 30-year follow-up of the Da Qing diabetes study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 191, 110048 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Metabolic syndrome and stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Clin. Neurosci. 40, 34–38 (2017).

Zhang, F. et al. Association of metabolic syndrome and its components with risk of stroke recurrence and mortality: a meta-analysis. Neurology 97, e695–e705 (2021).

Mozaffarian, D. Promise of improving metabolic and lifestyle risk in practice. Lancet 371, 1973–1974 (2008).

Yao, F. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of metabolic syndrome among adults in China from 2015 to 2017. Nutrients 13, 4475 (2021).

Park, H. S., Oh, S. W., Cho, S., Choi, W. H. & Kim, Y. S. The metabolic syndrome and associated lifestyle factors among South Korean adults. Int. J. Epidemiol. 33, 328–336 (2004).

Novo, S. et al. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) predicts cardio and cerebrovascular events in a twenty years follow-up: a prospective study. Atherosclerosis 223, 468–472 (2012).

Bos, D. et al. Atherosclerotic carotid plaque composition and incident stroke and coronary events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 1426–1435 (2021).

Boden-Albala, B. et al. Metabolic syndrome and ischemic stroke risk: Northern Manhattan study. Stroke 39, 30–35 (2008).

Takahashi, K. et al. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of ischemic stroke in women. Hypertens. Res. 30, 643–648 (2007).

Reeves, M. J. et al. Sex differences in stroke: epidemiology, clinical presentation, medical care, and outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 7, 915–926 (2008).

Gasbarrino, K., Di Iorio, D. & Daskalopoulou, S. S. Importance of sex and gender in ischaemic stroke and carotid atherosclerotic disease. Eur. Heart J. 43, 460–473 (2022).

Rexrode, K. M. et al. The impact of sex and gender on stroke. Circ. Res. 130, 512–528 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Association of age of onset of hypertension with cardiovascular diseases and mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 2921–2930 (2020).

Wang, L. et al. A prospective study of waist circumference trajectories and incident cardiovascular disease in China: the Kailuan cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 338–347 (2021).

Rapsomaniki, E. et al. Blood pressure and incidence of twelve cardiovascular diseases: lifetime risks, healthy life-years lost, and age-specific associations in 1·25 million people. Lancet 383, 1899–1911 (2014).

Mulligan, A. A., Lentjes, M. A. H., Luben, R. N., Wareham, N. J. & Khaw, K. Changes in waist circumference and risk of all-cause and CVD mortality: results from the European prospective investigation into cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 19, 238 (2019).

Yamaoka, K. & Tango, T. Effects of lifestyle modification on metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 10, 138 (2012).

Bornstein, S. R. et al. Practical recommendations for the management of diabetes in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 8, 546–550 (2020).

Cummings, M. J. et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York city: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 395, 1763–1770 (2020).

Landi, F. et al. Muscle loss: the new malnutrition challenge in clinical practice. Clin. Nutr. 38, 2113–2120 (2019).

Li, C. & Lumey, L. H. Impact of disease screening on awareness and management of hypertension and diabetes between 2011 and 2015: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Public Health 19, 421 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express our gratitude to the all the participants of CHARLS research team as well as each respondent who answered the questionnaire carefully.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (82370074) and Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2024AFC002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and H.L. wrote the main manuscript text and J.L. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4. W.L. prepared the manuscript for revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for CHARLS was granted by the Institutional Review Board at Peking University. Ethical approval for WEHECC was granted by the Wuhan University School of Medicine.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Liu, W., Li, H. et al. Changes of metabolic syndrome status alter the risks of cardiovascular diseases, stroke and all cause mortality. Sci Rep 15, 5448 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86385-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86385-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Associations of abdominal obesity and plasma fatty acids with microvascular diseases

Communications Medicine (2026)

-

Impact of phytosterol supplementation on metabolic syndrome factors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome (2025)

-

The additive effect of cardiopulmonary fitness and triglyceride-glucose index on the risk of metabolic syndrome

BMC Cardiovascular Disorders (2025)