Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) patient-derived xenografts (PDX) are relevant models for precision medicine. However, there are no collections derived from South American BC patients. Since ethnicity significantly impacts clinical outcomes, it is necessary to develop PDX models from different lineages. Our goals were to a) develop BC PDX from our population; b) characterize the expression of estrogen (ER), progesterone (PR), androgen (AR) and glucocorticoid (GR) receptors, basal and luminal cytokeratins, EGFR and HER2; c) identify PDX mutations; d) evaluate the response to treatments selected based on their biological and genetic features, and e) perform BC tissue cultures (BCTC) from PDX tissues and compare in vivo and ex vivo results. Surgical fragments were maintained in a culture medium and inoculated subcutaneously into untreated NSG female mice, or treated with estradiol pellets. Other fragments were fixed in formalin for diagnosis and immunohistochemistry, and a third piece was frozen at -80°C for molecular studies or whole exome-sequencing. Tumors were serially transplanted into NSG mice. Once the PDX was established, in vivo and ex vivo drug responses were evaluated. Eight PDX were established: two ER + [BC-AR685 (PR +) and BC-AR707 (PR-)], one from a triple-negative (TN) recurrence whose primary tumor was ER + (BC-AR485), one HER2 + (BC-AR474) and four TN primary tumors (BC-AR553, BC-AR546, BC-AR631 and BC-AR687). BC-AR685 had higher levels of PR isoform A than isoform B and was sensitive to mifepristone, tamoxifen, and palbociclib. BC-AR707 was inhibited by tamoxifen and testosterone. BC-AR474 was inhibited by trastuzumab and trastuzumab emtansine. BC-AR485 was sensitive to doxorubicin and resistant to paclitaxel in vivo and ex vivo. BC-AR687 carried a PIK3CA (C420R) mutation and was sensitive to alpelisib and mTOR inhibitors. All PDX expressed AR with varying intensities. GR and AR were co-expressed in the ER + tumors and in 3 TN PDX. We report the first PDX originated from South American countries that were genetically and biologically characterized and may be used in precision medicine studies. PDX expressing AR and/or GR are powerful tools to evaluate different endocrine treatment combinations even in TN tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths and the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women worldwide1. Luminal A tumors are mostly estrogen receptor α (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) positive ( +), with a low proliferation index and negative (-) for epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2). Luminal B tumors are ER + with low or null PR expression, have a high proliferation rate and may overexpress HER2. HER2 + tumors overexpress HER2, but are ER- and PR-. Basal tumors mainly consist of triple-negative (TN) tumors2,3.

In recent years, patient-derived xenografts (PDX) have gained attention as a platform for developing anticancer drugs. PDX models are created by transplanting a piece of the patient’s tumor into an immunosuppressed mouse. These models closely resemble the patient’s tumors4,5 and are considered more reliable than cancer cell lines for predicting therapeutic responses6,7,8. Extensive genomic studies have demonstrated that PDX models maintain a consistent overall global gene expression and activity profile compared to the parental tumors9, making them valuable for preclinical investigations. PDX models play a crucial role in advancing potential treatments to clinical trials, identifying tumor-specific biomarkers, and studying tumor progression mechanisms10.

It is worth noting that more than half of BC PDX models are TN, approximately 36% are ER + , and less than 10% are HER2 + 11,12. This distribution is linked to the characteristics of each subtype, with TN tumors being the most aggressive and easily engrafting as PDX13.

In addition to ER and PR, androgen (AR)14,15 and glucocorticoid (GR) receptors are emerging as candidates that may be important as prognostic factors and as therapeutic targets16. The association between AR or GR expression and patient prognosis is intricately linked to the specific molecular BC subtype17. There are, however, few studies that explore the co-expression of both receptors in the same samples.

Although large PDX collections exist in Europe and the USA, there is a need for PDX models originating from underrepresented populations. The percentage of BC PDX originated in patients classified as Hispanic or Latin may range from 17.618 to 0.8%19, but there are no collections available that originated from South American patients. Considering ethnic differences related to cancer risk and treatment response, developing PDX from these populations is a priority in the field20. In this study, we report the development and the genetic and biological characterization of eight BC PDX from South American women, including their repertoire of AR, GR, cytokeratins (CK 5/6 and CK8/18) and EGFR expression.

Methods

Animals

Immune compromised mice (NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ; NSG) were first acquired at the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) and were bred at IBYME Animal Facility. All animals were fed ad libitum and kept in air-conditioned room at 20 ± 2°C with a 12-h light/dark cycle period.

Animal ethics statement

Animal care and handling adhered to international guidelines and the regulations of the National Institute of Health. All studies were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the IBYME-IACUC Ethical Committee (Protocol 058/2017). At the end of the experiments, animals were euthanized using carbon dioxide chamber. Studies and analysis involving animals followed the recommendations in the ARRIVE guidelines.

Patient and ethical statement

Fresh tumor samples from BC patients who underwent tumor excision surgery at the Hospital "Magdalena V de Martínez" in General Pacheco were utilized. The protocol was approved by the Comité de Docencia e Investigación at the hospital (08/17), and the protocol and associated written informed consent were approved by the Enrique Segura IBYME IRB, 021–2017. The study was compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki. We affirm that no tissues were obtained from prisoners, and all samples were anonymized.

PDX generation

The following biobank generation workflow was established: at the time of tumor resection surgery, 3 tumor fragments were obtained and kept: i) in sterile DMEM/F12 culture medium for subsequent transplantation into NSG mice, ii) in 10% formalin for histopathological studies, and iii) frozen at -80°C for subsequent molecular studies (Fig. 1). The fragments from i) were inoculated subcutaneously (s.c.) by trocar into the right flank of 8-week-old female mice. The first successful passage of tumor tissue is designated as p0, and subsequent successful passages are designated as p1, p2, p3, pn, etc. At the time of tumor transplantation (p0), the operator was blind to the tumor subtype, so tumors were transplanted at minimum into one estradiol (E2)-treated and one untreated mouse, independent of the amount of ER. E2-pellets (0.5 mg) were developed in-house as already described21. In one occasion, the tumor was also transplanted inside a plastic cylinder following a method previously used to grow allogeneic tumors22. Tumor sizes (length x width) were recorded once a week using a Vernier caliper. The mice in which tumor uptake was not detected in the first 12 months were discarded. Tumors that reached a diameter greater than 8 mm were transplanted into other recipient mice, with or without E2 supplementation. In each passage the priority was the storage in cryotubes in liquid nitrogen. Procedures were performed as described by Alkema et al.23. Briefly, tumors were cut into pieces and placed into cryotubes containing 1.5 mL 90% FCS/ 10% DMSO. Cryotubes were transferred to a freezing container with isopropanol, kept in a − 80 °C freezer and then transferred to liquid nitrogen storage. If available, small pieces were kept frozen at -80°C and/or in formalin for tumor characterization. We considered that we had accomplished a PDX if at least three passages were performed and more than 3 cryotubes could be stored in liquid nitrogen.

PDX workflow. The resected tumor was divided into three fragments: one was placed in sterile culture medium for transportation and subsequent transplantation into NSG mice with or without E2 supplementation. The second fragment was formalin-fixed and paraffin- embedded (FFPE) for further histopathological studies. The third fragment was frozen at -80 °C for subsequent molecular studies. This methodology plus cryopreservation was repeated at each passage when possible. Drug sensitivity studies ex vivo and in vivo were conducted on selected established PDX models. ER: Estrogen receptors; PR: Progesterone receptors; p0: tumor originated directly from the patients`sample; pn successive passages into NSG mice, WES whole exome sequencing.

Immunohistochemistry

ER, PR, HER2 and Ki67 from patient´s sample were evaluated by the Hospital Facilities and the data was obtained from clinical records. In our laboratory these biomarkers were evaluated in the PDX formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded samples by standard immunohistochemistry (IHC) using the avidin–biotin peroxidase complex technique (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Staining against ER (ab108398, RRID:AB_10863604), PR (8757, RRID:AB_2797144), HER2 (29D8, RRID:AB_10692490), CK5/6 (4,382,432; MyBioSource), CK8/18 (4381493; MyBioSource), AR (ab74272, RRID:AB_1280747), GR (D8H2, RRID:AB_11179215), EGFR (C74B9, RRID:AB_2230881), Ki67 (ab15580, RRID:AB_443209) and pS6 (2215; RRID:AB_331682) was determined by IHC. The histological sections were observed under a Nikon Eclipse E200 optical microscope, and images were obtained using a digital Nikon camera connected to the microscope and the ACT-2U software. Ten fields were randomly selected, and the percentage of positive nuclei was quantified.

Western blot

In the PR + PDX, PR isoforms were measured in total fraction as described previously24.

Whole exome sequencing (WES)

Genomic DNA was isolated from the PDX samples. Briefly, the tumors were mechanically disaggregated with a scalpel and ground in a mortar in the presence of dry ice. Then, the crushed tumor was recovered in a 1.5 ml tube, incubated in digestion buffer for 3 h at 55°C and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was recovered and 1 volume of phenol–chloroform-isoamyl was added and mixed by inversion for several minutes. The resulting mixture was stored at room temperature and then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. The aqueous phase was transferred to a fresh tube and added ½ volume of 7.5 M ammonium acetate and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol and incubated for 30 min at -20°C. Once the DNA precipitation was completed, it was centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed with twice of salt solutions with 70% ethanol. Then, the pellet was dried on a thermal block at 37°C and finally resuspended in Tris–EDTA buffer. Samples were sent to Macrogen, Inc to be processed. WES was performed with the Agilent library kit SureSelect V6-Post, and 151 paired-end sequencing was performed with the Illumina HiSeq4000 platform. Total readings exceed 45 million and Q30 exceeds 94% per sample with an average coverage of 65X and an 80% of the bases on target regions were covered by more than 25 × per sample. The PDX WES Tumor-Only (Xenome) workflow was successfully completed with the PDX Argentina data using the Cancer Genomic Cloud platform (https://www.cancergenomicscloud.org/). Briefly, preprocessing steps include quality control filtering, removing adaptors, mouse reads were removed with xenome, trimmed reads were aligned to human genome (GRCh38), duplicate reads were removed with PicardTools, and Base-Recalibrator from the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) was used to adjust the quality of raw reads. Variants were called in Mutect2 using the Exome Aggregation Consortium database lifted over to GRCh38 as a germline reference. Variant calls were then filtered using GATK FilterMutectCalls25. Finally genomic variant interpretation including variant impact, annotation, scoring and ancestry inferring, was conducted with Opencravat26, Annovar27, Maftools28 and RAIDS29.

In vivo drug testing

Tumors were transplanted by trocar s.c. into the right inguinal flank of 2-month-old virgin NSG mice. E2 supplementation was used when needed. Tumor growth was measured twice a week using a Vernier caliper. Treatments were initiated when tumors reached a size of 25 – 40 mm2. Gold standard treatments for each tumor subtype were chosen: fulvestrant (AstraZeneca), 250 mg/kg/week s.c.30; nab-paclitaxel (Nab-PAX; Abraxane), 15 mg/kg/4 days a week intravenously (i.v.)31; pegylated doxorubicin liposomes (Doxplax, LKM), 4,5 mg/kg/week i.v31; tamoxifen citrate (Abcam), 5 mg/kg/5 days a week s.c.32; trastuzumab (Raffo), 15 mg/kg/3 days a week intraperitoneally (i.p.)33; trastuzumab emtansine (TDM1, Roche), 15 mg/kg/3 days a week i.p.33; mifepristone (Abcam), 6 mg/pellet s.c.34; palbocilib isethionate (MedChemExpress)32, 20 mg/kg/day s.c.; testosterone (Sigma), 20 mg/pellet s.c35; alpelisib (Piqray Novartis), 30mg/kg/5 days a week per os (p.o.)36, everolimus (Afinitor Novartis), 5 mg/kg/5days a week p.o.37 and rapamycin (MedChemExpress), 17.5mg/kg/2 days a week i.p32. Alpelisib and everolimus for in vivo use were obtained from pills that were pounded and dissolved in corn oil. Rapamycin vehicle was 5.2% Tween 80 and 5.2% PEG400 dissolved in PBS. At the end of the experiments, mice were euthanized. Tumors were excised, weighed and, along with other tissues, were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin for histological evaluation.

Ex vivo drug testing

BC tissue cultures (BCTC) from PDX tissues were performed as previously described38. Briefly, tissue slices (50–100 mm thick) were obtained using a vibratome (Precisionary Instruments) and incubated in DMEM/F12 without phenol red (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), with 10% fetal calf serum (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and the experimental drugs: doxorubicin HCL (Raffo, 1uM); paclitaxel (LKM, 50 nM); alpelisib (MedChemExpress, 100 nM) and Everolimus (MedChemExpress, 50 nM). After 48 h, tissues were harvested, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. To determine cell proliferation, Ki67 was evaluated by IHC and the percentage of Ki67 + cells over total viable cells was reported. In other experiments the expression of pS6 was registered and quantified.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software (Version 8.3.0 for Windows, GraphPad Software Inc.) was used for statistical analysis. Tumor growth curves were compared using two-way ANOVA. To compare tumor growth curves at end point or for comparing mean differences at end point between more than two treatments, one-way ANOVA analyses was used. Following ANOVA, multiple comparisons tests were conducted comparing the experimental groups to each other (Tukey’s test). To compare mean differences between two treatments, the Student’s t-test was used.

Results

PDX development and patient’s characteristics

PDX were attempted from 79 women who underwent surgery for BC primary tumors and/or lymph node (LN) metastasis resection. The study was interrupted in March 2020 due to COVID pandemic. Although PDX development was resumed after March 2022, the establishment of ongoing possible PDX is not included in this study. Ninety specimens obtained from the BC donors, 75 primary tumors, 14 synchronic LN and 1 LN recurrence were transplanted into NSG female mice, obtaining a total of 8 established PDX. Among them, 2 were originated from ER + primary tumors (BC-AR707 and BC-AR685), 1 from a TN LN recurrence whose primary tumor had been ER + (BC-AR485), 1 from a HER2 + primary tumor (BC-AR474) and the other 4 from TN primary tumors (BC-AR546, BC-AR553, BC-AR631 and BC-AR687).

The human origin of the PDX was corroborated with DNA sequencing (WES). Tumor subtype distribution of parental tumor and successful PDX can be observed in Fig. 2. As expected, a shift favoring the development of TN PDX was observed, showing a success rate of 38.5% (5/13) being the subtype with the highest number of PDX generated.

Parental tumor and PDX subtype distribution. (A) Out of 90 specimens obtained from 79 BC patients that were transplanted into NSG mice, a total of 8 PDX models were successfully established. Five patients were excluded from the analysis since no biomarker information was available. The numbers inside the graph indicate the number of cases. (B) Diagram showing ER/PR/HER2 status of the paired parental BC tumors and the successfully established PDX models. ER Estrogen receptor; PR Progesterone receptor; TN Triple-negative.

The NCI PDXNet (United States) and EuroPDX (Europe) have prepared a guideline of minimal clinical information that is necessary to know about the patients9. The information from patients whose tumors generated a PDX is included in Table 1. Remarkably, the overall survival (OS) of patients bearing TN tumors whose tumors engrafted, was significantly shorter (Median: 20.5 months; n = 4) than those that did not engraft (Median: > 66 months, n = 9; p < 0.05), confirming that PDX growth predicts poor prognosis. This cohort of patients was characterized by advanced stages and large tumor sizes (35–60 mm). The patients had their children at very young ages (median: 19; range: 15–28) and had a high number of pregnancies (median: 5; range: 1–11). All patients, except one who was born in Paraguay, were born in Argentina and their ancestry was indirectly obtained from the exome seq analysis which defined them as American (Additional file 1).

PDX growth pattern

The HER2 + PDX grew slowly in E2-treated mice, and after a few passages the rate of tumor growth increased. The ER + PR- PDX engrafted more rapidly than the ER + PR + tumor, and both grew preferentially in E2-treated mice. A decrease in tumor latencies was observed after several passages in ER + PDX. Contrarily, the TN PDX had a high growth rate already in p0 and grew with or without E2 administration. Regardless of tumor subtype, when frozen and thawed, there was a delay in tumor growth (Fig. 3).

Tumor growth curves of successive PDX passages. The individual growth curves of each PDX are plotted. Human tumors transplanted into NSG female mice represent p0, and the next passages are indicated with different colors. Growth of passages without E2 (no symbol), with E2 (star symbol), from thawed samples (circle symbol), or from thawed samples transplanted into E2-treated mice (triangle symbol) is presented. CP the tumor was inoculated inside a plastic cylinder, TNBC Triple-negative breast cancer, ER Estrogen receptor, PR Progesterone receptor.

PDX morphological characteristics and biological markers

The patient samples and their corresponding PDX counterparts showed similar morphological features and biomarkers expression. Tumor morphology images can be found in Additional file 2 and Fig. 4, respectively. The HER2 + PDX (BC-AR474) maintained HER2 overexpression and exhibited less stromal tissue compared to the parental tumor (Fig. 4A). PDX BC-AR685 showed a trend of growing inside the mouse mammary ducts resembling the areas of DCIS observed in the patient (Fig. 4B). In other areas both tumors also displayed features characteristic of invasive carcinomas with cord-like structures and budding glandular differentiation. The PDX models maintained ER and PR expression (Fig. 4C). PDX BC-AR707 exhibited moderate differentiation, frequent mitoses, limited stroma and abundant ER expression resembling the parental tumor (Fig. 4D).

Histological features and biomarker expression of the parental tumors and their respective PDX. (A) Histologic morphology (H&E; top) and HER2 expression (bottom) of parental or PDX BC-AR474. (B) DCIS observed in the patient’s sample and BC-AR685 PDX growing inside a mouse mammary duct (H&E). (C) Histological features (H&E; top), ER and PR expression of the parental invasive carcinoma and PDX BC-AR685. (D) Histological features (H&E; top) and ER expression (middle) of the patient’s tumor and of the PDX BC-AR707. No PR expression was observed in the parental tumor and in the PDX (bottom). The percentage of positive cells for each biomarker reported in the clinical record is indicated. Bar: 100 µM. H&E Hematoxylin and eosin staining; ER Estrogen receptors, PR Progesterone receptors.

While this study did not specifically focus on determining metastatic foci, micro-metastasis was confirmed in necropsies of both ER + PDX, the HER2 + PDX and the TN PDX BC-AR546 (Additional file 3).

In addition to the established clinical biomarkers, BC may express AR and/or GR, along with other biomarkers such as basal (CK5/6) and/or luminal (CK8/18) cytokeratins, or EGFR, which may help to subclassify tumors. Immunostaining results for both the original tumors and their corresponding PDX are presented in Additional file 4 and Fig. 5, respectively. Parental tumors were AR + except for 485. The paraffin block of the 687 patient was damaged and only the PDX was evaluated. All PDX samples analyzed stained positive for AR, with different intensities, being stronger in BC-AR546, BC-AR687 and BC-AR685 compared with others. Since BC-AR687 have, in addition, an intense CK8/18 + staining, and shows gland differentiation, it may belong to the LAR (luminal androgen receptor) subtype.

Cytokeratins, AR, GR and EGFR expression in PDX models. Representative immunohistochemistry images after staining for CK5/6, CK8/18, androgen receptors (AR), glucocorticoid receptors (GR) and epidermal growth fator receptors (EGFR). Antibodies used and procedures were described in the Materials and Methods section. Nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. Bar: 100 µM.

Regarding GR expression, stromal cells from all tumors were GR + , while tumor cells were GR + in all except for BC-AR474, BC-AR553, and BC-AR631. EGFR expression was positive with varying intensities in the HER2 + tumor and in the TN BC-AR485, BC-AR553 and BC-AR631. As mentioned previously, PDX BC-AR485 was a TN LN recurrence of a luminal tumor under treatment. Interestingly the recurrence showed strong CK5/6 expression and very low levels of the luminal biomarkers. TN tumors which express CK5/6 and EGFR may belong to the basal-like subtype.

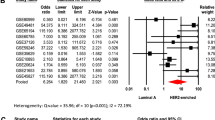

Whole exome sequencing analysis

Analysis of each PDX exome yielded single nucleotide variations (SNV). An initial filter included SNV with a population frequency under 10%. This analysis does not ponder the pathogenicity of each variation. The SNV distribution and classification through the 8 PDX is detailed in Additional file 5. Then, the impact of these variations on the functional capacity of the protein was retrieved from SIFT and Polyphen algorithms (Additional table 1). The 50 genes more frequently altered are listed in Fig. 6A, being MUC12 the top gene. Additionally, we found 6 pathways that are disrupted by these potentially pathogenic alterations: WNT, RAS, HIPPO, NOTCH, PI3K and TP53 (Fig. 6B). Several mutations that are not reported as pathogenic, may impact the protein structure, thus disrupting signaling pathways. WNT pathway was dysregulated in BC-AR474, BC-AR631, BC-AR687 and BC-AR707. BC-AR485, BC-AR546 and BC-AR553 presented alterations in the RTK-RAS pathway, while BC-AR546 and BC-AR685 presented alterations in the Hippo pathway. NOTCH seemed to be disrupted in BC-AR485 and BC-AR685. Finally, BC-AR687 and BC-AR685 exhibited the PI3K pathway affected.

Whole exome sequencing analysis (WES). Single nucleotide variations (SNV) and variant classification were analyzed in the 8 PDX with different filters: (A) Top 50 genes with SNV alterations. Colors indicate the type of alteration registered. (B) WNT, RAS, Hippo, NOTCH, PI3K and TP53 disrupted pathways are highlighted in pink, and above each pathway line, the altered genes involved are shown. (C) Alterations in breast cancer driver genes. Tumor mutation burden (TMB) of each PDX is shown at the top of Figures A and B, and estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), HER2 and KI67 expression at the bottom of Figures A and C.

Finally, we analyzed if the potential pathogenic variations alter BC driver genes, finding that all samples presented at least one driver gene with SNV (Fig. 6C). BC-AR687 presented a pathogenic BC mutation in PIK3CA (C420R) and BC-AR546 in TP53 (R175H), both of clinical relevance39,40.

Treatment responsiveness of HER2 + and ER + PDX

In all cases tumors were inoculated into NSG E2-treated mice as described in Materials and Methods. Mice bearing BC-AR474 tumors were treated with drugs that target HER2: trastuzumab and TDM1. Both treatments induced tumor regression (p < 0.001), being TDM1 more effective than trastuzumab (p < 0.05; Fig. 7A, left). Morphological characteristics in treated mice were in agreement with the observed changes in tumor size. Only few tumor nests surrounded by dense stromal tissue were observed in TDM1-treated mice (Fig. 7A, right). BC-AR685 tumors growing in E2-treated mice showed higher levels of PR isoform A than isoform B. Thus, mice bearing BC-AR685 PDX underwent treatments to target ER (tamoxifen), PR (mifepristone) and CDK4/6 (palbociclib). All treatments similarly inhibited tumor growth (p < 0.001; Fig. 7B, left). The differences in tumor weight at the end of the treatment were significant in mifepristone- and palbociclib-treated mice as compared with controls (p < 0.05; Fig. 7B, right). Finally, mice bearing BC-AR707 tumors were treated to target ER using tamoxifen, or AR using testosterone. Both treatments resulted in tumor regression (p < 0.001) and significantly reduced tumor weight (Fig. 7C, D).

Effects of therapeutic agents on tumor growth. Tumors were transplanted into female NSG mice (n = 3–4 mice /group) and treated with E2 pellets as described in Materials and Methods. Treatments were initiated when the tumors reached a size of ~ 25 mm2.(A) HER2 + PDX. left: Tumor growth curves after treatment with trastuzumab (TZ; 15 mg/kg/3 days per week i.p.) or trastuzumab emtansine (TDM1; 15 mg/kg/3 days per week i.p.) for 34 days. Right: Representative images (hematoxylin and eosin) of control, TZ- and TDM1-treated tumors showing reduced areas el epithelial nests surrounded by abundant stroma. (B) ER + PR + PDX. Tumor growth curve (left) and tumor weight (right) after treatment with tamoxifen citrate (TAM; 5 mg/kg/day, s.c.), mifepristone (MFP; 6 mg/pellet, s.c.) or palbociclib (PALBO; 20 mg/kg/5 days a week, s.c.) for 23 days. Western blot of a control tumor extract showing two bands corresponding to PR isoforms A and B. The uncropped image is shown in Additional File 6. Images of the excised tumors are shown in the right panel. (C) ER + PR- PDX: Tumor growth curve (left) and tumor weight (right) after treatment with TAM for 24 days as described above. (D) ER + PR- PDX: tumor growth curve (left) and tumor weight (right) after treatment with testosterone (TESTO; 20 mg/pellet) for 66 days. The X ± SD of tumor sizes or tumor weights are shown. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001. Bar: 100 µM.

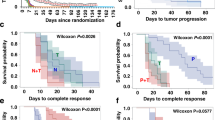

In vivo and ex vivo drug testing in TNBC PDX

TNBC BC-AR485 and BC-AR687 were selected to undergo in vivo and ex vivo assays. BC-AR485 primary tumor was ER + PR + HER2-, but the recurrence was TN. Therefore, we chose to treat the PDX with fulvestrant and with the chemotherapeutic agents paclitaxel (albumin-bound) and doxorubicin (pegylated liposomes). Figure 8A shows the growth curves after 18 days of treatment. Doxorubicin was the only therapeutic agent that significantly inhibited tumor growth (p < 0.001). Paclitaxel induced a slight decrease in tumor size that did not reach statistical significance and fulvestrant had no inhibitory effect. Ki67 expression was evaluated in excised tumors by IHC (Fig. 8B). Doxorubicin induced an extensive necrosis, but the remaining treatment-resistant tumor cells maintained their proliferative ability (Fig. 8B, arrow), so we did not detect a decrease in Ki67 expression as expected. Typical features of paclitaxel treatment, such as the presence of cells with macronuclei were observed in paclitaxel-treated tumors, however no statistically significant inhibition in Ki67 staining percentage was registered (Fig. 8B, arrow).

Effect of therapeutic agents on the growth of TNBC PDX in vivo and ex vivo. (A) BC-AR485 growth curves: Tumors were transplanted by trocar into NSG female mice (n = 4/group). When the tumors reached a size of ~ 25 mm2, fulvestrant (FULVE; 250 mg/kg/week s.c.), nab-paclitaxel (Nab-PAX; 15 mg/kg/4 days per week i.v.), and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (DOXO-L; 4.5 mg/kg/week i.v.) treatments were initiated and continued for 18 days. Tumor size was measured every 2–3 days and plotted. (B) Ki67 expression. At the end of the experiment, tumors were excised, processed for IHC studies and the expression of Ki67 was evaluated. The X̅ ± SD of 10 randomly fields were quantified and a representative image is shown. Black arrow shows an extensive area of necrosis (DOXO-L) and macronuclei induced treatment (Nab-PAX). (C) BC-AR687 growth curves. Tumors were transplanted by trocar into NSG female mice (n = 4/group). When the tumors reached a size of ~ 25 mm2, mice were treated with everolimus (EVERO-a, Afinitor Novartis) 5 mg/kg/5days a week p.o., alpelisib (ALPE-p, Piqray Novartis), 30mg/kg/5 days a week per os (p.o.) and rapamycin (RAPA, MCE) 17.5mg/kg/2 days a week intraperitoneally (i.p.). (D) Ki67 expression. The X̅ ± SD of 10 randomly fields were quantified and a representative image is shown. (E) Scheme of breast cancer tissue cultures (BCTC) from PDX. Tumors were excised, cut in thin slices with a Vibratome and pieces were cultured for 48 hs with therapeutic agents. Then tissues were formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin to quantify pS6 and KI67 expression evaluated by immunohistochemistry (IHC). (F) The X̅ ± SD of 10 randomly fields were quantified and representative images are shown. Top: Ki67 index in control, DOXO- or PAX-treated cultures. Bottom: pS6 index in alpelisib (ALPE)- or everolimus (EVERO)-treated cultures. *: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001; ****: p < 0.0001. Bar: 100 µM.

BC-AR687 carries a PIK3CA mutation (C420R). Luminal BC patients that carry this mutation are candidates for alpelisib treatment. On the other hand, the possibility to treat TNBC patients with PIK3CA mutations with this type of agents is being explored. Thus, we tested the effects of alpelisib and two mTOR inhibitors, everolimus and rapamycin, which target the same pathway on tumor growth. Remarkably, a similar inhibitory effect was observed with the three therapeutic compounds, both in tumor growth evaluations (Fig. 8C, p< 0.05 and p < 0.01) and Ki67 expression (Fig. 8D ;p< 0.001).

Then, we evaluated drug sensitivity in ex vivo assays as indicated in Fig. 8E. BCTC performed in BC-AR485 showed that only doxorubicin treatment reduced the Ki67 staining (p < 0.05), indicating a concordance between the in vivo growth curves data and the ex vivo results (Fig. 8F, top). In the BC-AR687 ex vivo model, alpelisib and everolimus were shown to inhibit pS6 expression, a biomarker of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activity. Only everolimus reached statistical significance.

Discussion

We have successfully created and studied PDX models focusing on their expression of steroid hormones representing the three clinical BC subtypes. There are over 1000 PDX models developed worldwide41,42,43,, but ours is the first BC PDX model from a South American population. Using the Exome-Seq data, we were able to determine that the patients mainly matched with the American lineage. These models, along with others, may be useful in studies requiring drug testing in a variety of PDX models with different ancestries.

Understanding the genetic heritage of a population is crucial for learning its sensitivity to certain diseases, response to treatments, and clinical manifestations. Argentina has a significant history of unique and unrepeatable ethnic mixing, making it essential to study the genetic characteristics of the population. The PoblAR project, initiated in 2016, is the first repository of genomic data in Argentina and is still in the data collection stage. The analysis of population characteristics is a recent development in our history, and there is currently no other BC PDX Biobank in Argentina or Latin America. The PDX models established by this project, mostly from the boundaries of Buenos Aires city and from immigrants from Paraguay and Bolivia, will allow for appropriate models for precision medicine studies in our region.

Although compelling data indicates that BC PDX performed from metastatic sites engraft better than primary tumors42,43,44,45, there is little information regarding the engraftment of synchronic LN BC metastases. In our study, 15 synchronic LN metastases were transplanted together with the primary tumors, and unexpectedly, only the latter originated tumors that could be successfully transplanted. In agreement with the observation that the LN status at diagnosis is associated with successful PDX establishment18, 5 out of 7 patients were LN + at the time of surgery. Overall, the characteristics of the patients who generated PDX models, shared various criteria with those described by others as related to better engraftment: most patients were young46, had large tumor sizes46, had a high histologic grade46,47 with high Ki67 labeling index18,46, and had “cold” tumors12. It has been reported that non-immune tumors engraft better than those with a high immune component12.

The engraftment rate was lower than those obtained by others (reviewed in48). This might have been due to a higher rate of mortality observed in E2-treated intact mice, or because the number of mice originally transplanted per PDX was low. To increase the rate of engraftment of luminal BC several authors inoculated tumor cells inside the mouse mammary ducts obtaining encouraging results49,50. In these cases, in vivo imaging methods are necessary to check tumor outgrowth. We transplanted the tumors s.c. into the flank next to the 4th mammary gland so that tumors can be easily measured with a caliper. Using this method, tumor transplants may also experience intraductal growth as shown in Fig. 4B. Since Saal et al., showed that allograft tumor growth was obtained when tumor cells were inoculated inside a s.c. implanted glass cylinder22, this methodology with some modifications was attempted. Interestingly, one of the luminal PDX was established using this method. The success might be circumstantial, or the implantation in this type of device may provide some advantage to sustain ER + tumor growth, an observation that deserves further investigation. As mentioned by others11, TN tumors showed a higher growth rate compared to ER + or HER2 + tumors. Additionally, tumors from patients who had received previous treatment, engraft much more efficiently than treatment-naive tumors4,46. BC-AR485 originated from an LN recurrence from a patient who had a luminal BC that was treated with chemotherapy and tamoxifen. Surprisingly, this tumor recurrence became TN. Changes from luminal subtype (ER +) to TN subtype after chemotherapy treatment have been reported in 1651 or 30%52 of the cases and the discordance may also be bi-directional (from positive to negative and vice versa)53. Most cells that remain resistant to the chemotherapy are stem cells54,55,56,57,, and this might have occurred in the 485 patient since the tumor recurrence and the PDX also expressed basal cytokeratins (CK5/6). The PDX was sensitive to doxorubicin, and resistant to taxanes. The patient received anthracycline + cyclophosphamide as a first-line treatment. PDX generally retain drug-sensitivity profiles as the original tumors, but PDX derived from treatment-resistant tumors can become sensitive again after xenografting due to the drug holiday effect, where treatment is discontinued until the PDX is generated. This has been observed mainly in melanoma and lung adenocarcinomas.

In addition to the classic steroid hormone receptors ER and PR, AR14 and GR55,56,57,58,59 are emerging as potential targets in BC therapy. Although several studies evaluate AR or GR expression, there is limited information regarding the co-expression of both receptors in the different BC subtypes.

AR is expressed in 70–80% of all BC: approximately 80% of ER + tumors, 50% of HER2 + tumors and 10–30% of TN breast tumors14,48,60. As expected, both luminal PDX were AR + . AR may be located in the cytoplasm, and in the presence of an androgenic ligand, AR can shuttle to the nucleus. All TN PDX had different intensities of nuclear AR staining, and those that showed strong nuclear AR and CK8/18 staining may belong to the LAR subtype. This subtype may represent less than 10% of TN PDX61. TNBC from the basal-like subgroups 1 and 2 may also express AR at lower levels but they express, in addition, basal cytokeratins such as CK5/6. BC-AR687 carries a PIK3CA mutation (C420R) frequently observed in luminal and apocrine LAR tumors62. Alpelisib is recommended together with endocrine therapies in luminal BC patients carrying this mutation63,64. Interestingly, BC-AR687 was inhibited by alpelisib and by two mTOR inhibitors.

There is also controversy about whether AR agonists or antagonists should be used to treat AR + BC. Testosterone had similar inhibitory effects as tamoxifen in the ER + PR- PDX in the presence of E2. It is known that dihydrotestosterone inhibits estrogen-induced cell proliferation in ZR-75–1 BC cells65 and may stimulate or inhibit the growth of basal-like TN PDX expressing low AR levels66. RAD140 is an AR agonist with similar inhibitory effects as fulvestrant in 3 PDX from the HBCx-series67. Similarly, enobosarm, another AR agonist, inhibited tumor growth of PDX-bearing wild-type or mutant ER68.

Between 30 and 70% of invasive BC express GR48. High GR expression correlates with poor prognosis in ER- and good prognosis in ER + BC17,69. In our cohort, mild GR expression was observed in the ER + PDX. Intense nuclear staining was observed in two AR + TN PDX (BC-AR687 and BC-AR546), and in the TN recurrence (BC-AR485). These TN PDX may be useful to discriminate the role of mifepristone acting as antiandrogen or antiglucocorticoid vs. its antiprogestational effects70. A GR signature was found to be higher in PDX derived from patients with residual cancer burden compared to those derived from patients with complete pathological response16 and, as mentioned previously, this correlates with a worse prognosis. To our knowledge, there is no information regarding GR expression by IHC in other BC PDX. Remarkably stromal cells showed an intense nuclear staining.

The EGFR pathway has become a potential target in the basal-like subtype because at least 50% of basal-like tumors express EGFR as assessed by IHC and may be treated with EGFR inhibitors. Luminal B tumors may also express EGFR, while luminal A show low expression of most of the genes examined in the HER family pathway71. In this regard, high EGFR was observed in the HER2 + PDX, the TN recurrence (BC-AR485), and in TN BC-AR553. The ER + PDX were almost negative for EGFR.

The HER2 + PDX BC-AR474 had a good response to trastuzumab and to TDM1, with the latter showing a higher efficacy than the former. The doses were similar to those used by others72. This PDX is useful to test the effect of combination therapies or to improve the effect of HER2-directed therapies.

Regarding the ER + PDX generated, BC-AR685 exhibited a growth pattern resembling intraductal growth, which is similar to the images observed with T47D-YB xenografts31. While we couldn’t conduct a PR western blot of the original tumor, the PDX showed higher levels of PRA than PRB when it was growing in the presence of estrogens. The tumor growth was inhibited by mifepristone treatment, as expected from previous data38. Similar inhibitory effects were observed with tamoxifen and palbociclib treatments.

A significant challenge in the PDX field is the high cost of experiments designed for drug testing. To address this, various culture techniques are being utilized10,12. In this study, we adapted the BCTC technology originally performed directly from the patient’s sample38. Initially, we used expensive filters to adhere the tumor slices, but later, we adapted a similar technology using dental sponges instead of filters73. This technology, along with organoids and spheroids derived from PDX, closely recapitulates the morphological features of the parental tumors and offers promising opportunities for drug screening and facilitating chemical discovery6,74. The main advantage of using tissue slice cultures instead of cell suspensions is that, in the former, the tumor architecture is maintained. However, the technique requires training and the expertise of a pathologist to conduct tissue quality assurance.

There are two potential limitations of this study: the relatively low number of PDX generated compared to other collections and the fact that ancestry data were indirectly obtained from Exome-Seq data.

Conclusion

In this report, we present the development and complete characterization of 8 PDX with a South American background for use in BC research.

Data availability

Exome sequencing data is publicly available at the SRA repository (PRJNA1158830).

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Perou, C. M. et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 406, 747–752 (2000).

Prat, A. & Perou, C. M. Deconstructing the molecular portraits of breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 5, 5–23 (2011).

Byrne, A. T. et al. Interrogating open issues in cancer precision medicine with patient-derived xenografts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 17, 254–268 (2017).

Woo, X. Y. et al. Conservation of copy number profiles during engraftment and passaging of patient-derived cancer xenografts. Nat. Genet. 53, 86–99 (2021).

Yoshida, G. J. Applications of patient-derived tumor xenograft models and tumor organoids. J. Hematol. Oncol. 13, 4 (2020).

DeRose, Y. S. et al. Tumor grafts derived from women with breast cancer authentically reflect tumor pathology, growth, metastasis and disease outcomes. Nat. Med. 17, 1514–1520 (2011).

Souto, E. P., Dobrolecki, L. E., Villanueva, H., Sikora, A. G. & Lewis, M. T. In vivo modeling of human breast cancer using cell line and patient-derived xenografts. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 27, 211–230 (2022).

Meehan, T. F. et al. PDX-MI: minimal information for patient-derived tumor xenograft models. Cancer Res. 77, e62–e66 (2017).

Singhal, S. S. et al. Recent advancement in breast cancer research: insights from model organisms-mouse models to zebrafish. Cancers 15, 2961. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15112961 (2023).

Dobrolecki, L. E. et al. Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models in basic and translational breast cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 35, 547–573 (2016).

Petrosyan, V. et al. Immunologically “cold” triple negative breast cancers engraft at a higher rate in patient derived xenografts. N.P.J. Breast Cancer https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-022-00476-0 (2022).

Cao, C., Lu, X., Guo, X., Zhao, H. & Gao, Y. Patient-derived models: Promising tools for accelerating the clinical translation of breast cancer research findings. Exp. Cell. Res. 425, 113538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113538 (2023).

Collins, L. C. et al. Androgen receptor expression in breast cancer in relation to molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses’ Health Study. Mod. Pathol. 24, 924–931 (2011).

Hickey, T. E. et al. The androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat. Med. 27, 310–320 (2021).

West, D. C. et al. Discovery of a glucocorticoid receptor (GR) activity signature using selective gr antagonism in er-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 24, 3433–3446 (2018).

Snijesh, V. P. et al. Differential role of glucocorticoid receptor based on its cell type specific expression on tumor cells and infiltrating lymphocytes. Transl. Oncol. 45, 101957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2024.101957 (2024).

Echeverria, G. V. et al. Predictors of success in establishing orthotopic patient-derived xenograft models of triple negative breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 9(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41523-022-00502-1 (2023).

Goetz, M. P. et al. Tumor Sequencing and Patient-Derived Xenografts in the Neoadjuvant Treatment of Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109, djw06. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw306 (2017).

Yagishita, S. et al. Characterization of the large-scale Japanese patient-derived xenograft (J-PDX) library. Cancer Sci. 112, 2454–2466 (2021).

Sahores, A. et al. Novel, low cost, highly effective, handmade steroid pellets for experimental studies. PLoS One 8, e64049. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064049 (2013).

Saal, F., Colmerauer, M. E., Braylan, R. C. & Pasqualini, C. D. Tumor growth in allogeneic mice bearing a lucite cylinder. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 49, 451–458 (1972).

Alkema, N. G. et al. Biobanking of patient and patient-derived xenograft ovarian tumour tissue: efficient preservation with low and high fetal calf serum based methods. Sci. Rep. 5, 14495. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14495 (2015).

Helguero, L. A. et al. Progesterone receptor expression in medroxyprogesterone acetate-induced murine mammary carcinomas and response to endocrine treatment. Breast Cancer ResTreat 79, 379–390 (2003).

Evrard, Y. A. et al. Systematic establishment of robustness and standards in patient-derived xenograft experiments and analysis. Cancer Res. 80, 2286–2297 (2020).

Pagel, K. A. et al. Integrated Informatics Analysis of Cancer-Related Variants. J.C.O. Clinical Cancer Inform. 4, 310–317 (2020).

Yang, H. & Wang, K. Genomic variant annotation and prioritization with ANNOVAR and wANNOVAR. Nature Protoc. 10, 1556–1566 (2015).

Mayakonda, A., Lin, D. C., Assenov, Y., Plass, C. & Koeffler, H. P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 28, 1747–1756 (2018).

Belleau, P., Deschenes, A., Chambwe, N., Tuveson, D. A. & Krasnitz, A. Genetic ancestry inference from cancer-derived molecular data across genomic and transcriptomic platforms. Cancer Res. 83, 49–58 (2023).

Giulianelli, S. et al. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates progestin-induced mammary tumor growth by interacting with progesterone receptors at the cyclin D1/MYC promoters. Cancer Res. 72, 2416–2427 (2012).

Sequeira, G. et al. The effectiveness of nano chemotherapeutic particles combined with mifepristone depends on the PR isoform ratio in preclinical models of breast cancer. Oncotarget 5, 3246–3260 (2014).

Rodriguez, M. J. et al. Targeting mTOR to overcome resistance to hormone and CDK4/6 inhibitors in ER-positive breast cancer models. Sci. Rep. 13, 2710. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29425-y (2023).

Yu, L. et al. Eradication of growth of HER2-positive ovarian cancer with trastuzumab-DM1, an antibody-cytotoxic drug conjugate in mouse xenograft model. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 24, 1158–1164 (2014).

Abascal, M. F. et al. Progesterone receptor isoform ratio dictates antiprogestin/progestin effects on breast cancer growth and metastases: A role for NDRG1. Int. J. Cancer 150, 1481–1496 (2022).

Chuu, C. P. et al. Inhibition of tumor growth and progression of LNCaP prostate cancer cells in athymic mice by androgen and liver X receptor agonist. Cancer Res. 66, 6482–6486 (2006).

Cataldo, M. L. et al. The effect of the alpha-specific PI3K inhibitor alpelisib combined with anti-HER2 therapy in HER2+/PIK3CA mutant breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 13, 1108242. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.1108242 (2023).

Mazumdar, A. et al. Targeting the mTOR pathway for the prevention of ER-negative breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 15, 791–802 (2022).

Rojas, P. A. et al. Progesterone receptor isoform ratio: a breast cancer prognostic and predictive factor for antiprogestin responsiveness. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 109, djw317. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw317 (2017).

Kakudo, Y., Shibata, H., Otsuka, K., Kato, S. & Ishioka, C. Lack of correlation between p53-dependent transcriptional activity and the ability to induce apoptosis among 179 mutant p53s. Cancer Res. 65, 2108–2114 (2005).

Zhang, H. et al. Comprehensive analysis of oncogenic effects of PIK3CA mutations in human mammary epithelial cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 112, 217–227 (2008).

Lewis, M. T. & Caldas, C. The power and promise of patient-derived xenografts of human breast cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 14, a041329. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a041329 (2024).

Marangoni, E. et al. Patient-derived tumour xenografts as models for breast cancer drug development. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 26, 556–561 (2014).

Martins-Filho, S. N. et al. EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinomas from patients who progressed on EGFR-inhibitors show high engraftment rates in xenograft models. Lung Cancer 145, 144–151 (2020).

Chen, C. et al. The essential factors of establishing patient-derived tumor model. J. Cancer 12, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.51749 (2021).

Cottu, P. et al. Modeling of response to endocrine therapy in a panel of human luminal breast cancer xenografts. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 133, 595–606 (2012).

Lee, J. et al. Factors associated with engraftment success of patient-derived xenografts of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 26, 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-024-01794-w (2024).

Zhang, X. et al. A renewable tissue resource of phenotypically stable, biologically and ethnically diverse, patient-derived human breast cancer xenograft models. Cancer Res. 73, 4885–4897 (2013).

Matthews, S. B. & Sartorius, C. A. steroid hormone receptor positive breast cancer patient-derived xenografts. Horm. Cancer 8, 4–15 (2017).

Richard, E. et al. The mammary ducts create a favourable microenvironment for xenografting of luminal and molecular apocrine breast tumours. J. Pathol. 240, 256–261 (2016).

Fiche, M. et al. Intraductal patient-derived xenografts of estrogen receptor alpha-positive breast cancer recapitulate the histopathological spectrum and metastatic potential of human lesions. J. Pathol. 247, 287–292 (2019).

Matsumoto, A. et al. Prognostic implications of receptor discordance between primary and recurrent breast cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 701–708 (2015).

He, Y. et al. Clinical significance and prognostic value of receptor conversion after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Front. Surg. 9, 1037215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.1037215 (2022).

Yilmaz, C. & Cavdar, D. K. Biomarker discordances and alterations observed in breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: causes, frequencies, and clinical significances. Curr. Oncol. 29, 9695–9710 (2022).

Prieto-Vila, M., Takahashi, R. U., Usuba, W., Kohama, I. & Ochiya, T. Drug resistance driven by cancer stem cells and their niche. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18122574 (2017).

Pan, D., Kocherginsky, M. & Conzen, S. D. Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor is associated with poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 71, 6360–6370 (2011).

Kach, J., Conzen, S. D. & Szmulewitz, R. Z. Targeting the glucocorticoid receptor in breast and prostate cancers. Sci. Transl. Med 7, 305ps319. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7531 (2015).

Abduljabbar, R. et al. Clinical and biological significance of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 150, 335–346 (2015).

Skor, M. N. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism as a novel therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 6163–6172 (2013).

Vilasco, M. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 130, 1–10 (2011).

Vera-Badillo, F. E. et al. Androgen receptor expression and outcomes in early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106, djt319. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djt319 (2014).

Coussy, F. et al. Response to mTOR and PI3K inhibitors in enzalutamide-resistant luminal androgen receptor triple-negative breast cancer patient-derived xenografts. Theranostics 10, 1531–1543 (2020).

Lehmann, B. D. et al. PIK3CA mutations in androgen receptor-positive triple negative breast cancer confer sensitivity to the combination of PI3K and androgen receptor inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res. 16, 406. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-014-0406-x (2014).

Juric, D. et al. Alpelisib plus fulvestrant in PIK3CA-altered and PIK3CA-Wild-type estrogen receptor-positive advanced breast cancer: a phase 1b clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 5(2), e184475. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4475 (2019).

Chakravarty, D. et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. J.C.O. Precis. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.17.00011 (2017).

Poulin, R., Baker, D., Poirier, D. & Labrie, F. Androgen and glucocorticoid receptor-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation by medroxyprogesterone acetate in ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 13, 161–172 (1989).

Wang, X. et al. Functional characterization of androgen receptor in two patient-derived xenograft models of triple negative breast cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 206, 105791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105791 (2021).

Yu, Z. et al. Selective androgen receptor modulator rad140 inhibits the growth of androgen/estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer models with a distinct mechanism of action. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 7608–7620 (2017).

Ponnusamy, S. et al. Androgen receptor is a non-canonical inhibitor of wild-type and mutant estrogen receptors in hormone receptor-positive breast cancers. iScience. 21(341), 358 (2019).

Mitre-Aguilar, I. B. et al. The role of glucocorticoids in breast cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. 30, 298–314 (2022).

Elia, A. et al. Antiprogestins for breast cancer treatment: We are almost ready. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 241, 106515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2024.106515 (2024).

Hoadley, K. A. et al. EGFR associated expression profiles vary with breast tumor subtype. BMC Genomics 8, 258. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-8-258 (2007).

Irie, H. et al. Acquired resistance to trastuzumab/pertuzumab or to T-DM1 in vivo can be overcome by HER2 kinase inhibition with TAS0728. Cancer Sci. 111, 2123–2131 (2020).

Gustafsson, A. et al. Patient-derived scaffolds as a drug-testing platform for endocrine therapies in breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 11, 13334. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92724-9 (2021).

Gordon, M. A. et al. Synergy between Androgen Receptor Antagonism and Inhibition of mTOR and HER2 in Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16, 1389–1400 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Virginia Novaro, for sharing alpelisib, everolimus and rapamycin, to Ramiro Perrota and Mariana Salatino for sharing trastuzumab and TDM1, and to Sales, Baron, Bigand and Williams Foundations for their continuous support. The authors thank Dennis Dean and Jeffrey Grover from Seven Bridges Genomics (Charlestown, Massachusetts) for their advice on implementing the PDXnet workflow at CGC.

Funding

The study was supported by: Asistencia financiera IV, Instituto Nacional del Cáncer, 2018–2019, PICT- ANPYT 2021–029, both to C. Lanari and with continuous support of Fundación Sales.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S. participated starting with the first PDX and BCTC; G.P. continued with the PDX development, PDX characterization and drafted and revised the manuscript; L.A. continued with the PDX establishment and BCTC experiments under the supervision of P.A.R.; M.C. and C.A.L. participated in treatment experiments; A.E. and M.A. performed the exome-seq analysis and designed the corresponding figures, S.I.V. analyzed the morphological features of tumors and supervised IHC assays; P.M.V., J.B. and E.S. collaborated with human tissue supply, consented the patients and provided clinical record´s data; C.L. designed the project, supervised the study and drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. CAL, CL, MA, and PAR are members of CONICET research career, MC, AE, GP are fellows from CONICET, LA is fellow from ANPCYT. GS participated as fellow from CONICET, now he works at the “Dr. Arturo Oñativia Hospital” in Salta, Argentina. SIV is now an independent pathologist.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients signed a written informed consent to participate in this project. The study was approved by the Hospital´s authorities and from the Enrique Segura IBYME IRB # 021–2017. Animal experiments were approved by the IBYME-IACUC committee (058–2017).

Consent for publication

All authors agree with the contents of the manuscript and agree for its publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pataccini, G., Elia, A., Sequeira, G. et al. Steroid hormone receptors, exome sequencing and treatment responsiveness of breast cancer patient-derived xenografts originated in a South American country. Sci Rep 15, 2415 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86389-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86389-x