Abstract

With the rapid development of new energy industry, the demand for lithium resources continues to rise. The salinity-gradient solar pond (SGSP) technology is used to extract the lithium carbonate from Zabuye salt lake brine in the Tibet Plateau of China. Years of production practice proved that due to the unsatisfactory quality and insufficient amount of lithium-rich brine used to make the SGSP, the yield and grade of lithium concentrate in the solar pond has been seriously affected. In this paper, it has been investigated that the change rule of brine composition with different brine mixing ratios through the same/cross-year brine mixing laboratory experiments and the cross-year brine mixing production test. The optimal brine mixing ratio of winter concentrated brine and summer brine, the relevant operation parameters and the yield increase effect of lithium concentrate in the solar pond are obtained. The results show that the cross-year brine mixing method can not only significantly improve the yield and grade of lithium carbonate, but also alleviate the pressure of brine production in salt field. It is suggested that the SGSP technology coupled with the cross-year brine mixing method should be given priority in the production of lithium carbonate in Zabuye mining area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lithium is the lightest alkali metal element in the periodic table with the unique physicochemical characteristics1,2. As a vital raw material in the new energy field, lithium and its compounds has been widely used in various fields such as batteries, metallurgy, glass, ceramics, lubricants, pharmaceuticals, nuclear industry and polymer materials, which is known as the "energy metal of the twenty-first century" and “white petroleum”. According to the report of the United States Geological Survey in 20223, the global proven lithium reserves are approximately 89 million tons of metallic lithium, mainly present in solid lithium ores, clay, salt lake brine and seawater, of which more than 60% of lithium resources exist in the salt lake brine4,5. With the establishment of “dual carbon” target and the arrival of the turning point of the energy storage market economy, the global demand for lithium resources is accelerating6. Based on the comprehensive considerations of environmental protection and production costs, the development prospect of lithium extraction from salt lake brine is recognized as more favorable than that from solid lithium ores, which may become the main way to obtain lithium resources in the future. In recent years, the research and development of efficient and low-cost lithium extraction technology has become a hotspot in the key areas of salt lake strategic resources7.

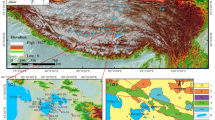

China is a large country of lithium resources with abundant reserves and high degree of concentration. The lithium resources in brine account for more than 80% of the total resources, and the hydrochemical types include carbonate-type, sulfate-type and chloride-type5,8. At this stage, the lithium extraction technology from salt lake brine mainly includes precipitation method, adsorption method, ion membrane electrodialysis method, calcination method and solar pond method, etc., which is suitable for different types of brine9,10,11,12. The carbonate-type brine is considered to have the optimal extraction condition because of the lowest magnesium-lithium ratio, and the solar pond method is the most traditional and mature process for lithium extraction from this type of brine. The carbonate-type salt lakes in China are mainly distributed in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and the typical representative of the successful industrialized development of lithium resources in salt lakes by using the solar pond method is Zabuye salt lake, located in Zhongba County, Xigaze Prefecture, Tibet. The location map of Zabuye salt lake is shown in Fig. 1.

Location map of Zabuye salt lake, Tibet (modifed from Ref.13).

Zabuye salt lake is currently the only known carbonate-type salt lake in the world that can naturally deposit lithium carbonate, and also a rare comprehensive large-scale salt lake deposit of lithium, boron, potassium and cesium11. The lithium extraction process from Zabuye salt lake brine is divided into two stages: brine production and lithium salts crystallization. The stage of brine production mainly involves pre-separating minerals such as NaCl, alkali, sylvine, glaserite and borax from the brine through natural evaporation in the salt fields, in order to obtain the lithium-rich concentrated brine. During the stage of lithium salts crystallization, the salinity-gradient solar pond (SGSP) is the core component. The prepared lithium-rich concentrated brine is introduced into the crystallization pond through the transportation pipeline, and a fresh water layer is laid on the surface of the brine to make a SGSP. By relying on solar radiation, the lithium-rich concentrated brine in the lower part of the solar pond heats up and precipitates lithium carbonate crystals14. On the basis of the traditional SGSP, the nucleation matrix assisting the stereo-crystallization of lithium carbonate is introduced to expand the crystallization surface, which promotes the full precipitation of lithium carbonate from the brine and accelerates the crystallization rate of lithium carbonate, so as to effectively improving the yield and grade of lithium concentrate in the single solar pond. The structure diagram of SGSP with stereo-crystallization process is shown in Fig. 215.

Structure diagram of SGSP with stereo-crystallization process (modifed from Ref.15).

The production and operation practice of lithium carbonate in the Zabuye mining area has proved that there are technical bottlenecks in the lithium extraction technology with SGSP, such as slow brine heating rate, small temperature-rising range, long production cycle, low lithium yield and grade. It is considered that the low CO32‑ concentration and low initial temperature of the lithium-rich brine are one of the important factors restricting the lithium yield and grade of the solar pond. In actual production, the lithium-rich brine poured into the crystallization pond is generally winter concentrated brine. Although the Li+ concentration in the brine has already been enriched to a higher level at this time, the CO32‑ concentration and the initial temperature of the brine are still low. It requires a long period of accumulating the heat and heating the brine up to precipitate the lithium carbonate. Due to incomplete precipitation of Li+, the crystallization effect of lithium carbonate is not ideal with the low yield and grade of lithium concentrate, while the Li+ concentration in the discharged tail brine is still high, resulting in the serious lithium loss. In recent years, the structure and operation of SGSP have been thoroughly studied and improved. The optimization means include the precipitation method with sodium carbonate, cyclic disturbance method and stereo-crystallization process, etc.15,16,17. However, there is no specific research work and effective measures on how to increase the CO32− concentration and initial temperature of lithium-rich brine poured into the crystallization pond.

The brine mixing method is a common operation technology in the production of salt fields, mainly through the blending of different components of brine to obtain the target brine that meets the subsequent production. The purpose of considering the brine mixing method here is to increase the CO32- concentration of the mother liquor for lithium extraction. In this paper, the comparative experiments of lithium precipitation by mixing and heating the brine such as the same-year and cross-year laboratory experiment and the cross-year production test have been carried out by using different qualities of brine from different stages, in order to understand the influence of brine mixing ratio on the precipitation rate and composition of solid salt minerals, so as to find the appropriate brine mixing ratio for practical production. The optimal brine mixing ratio of winter concentrated brine and summer brine, relevant operation parameters and the yield increase effect of lithium concentrate were obtained, and the action mechanism of brine mixing was comprehensively analyzed, providing the theoretical support for the actual process operation. The mixed brine pouring into the crystallization pond could be used as the mother liquor for lithium extraction to achieve the purpose of improving the yield and grade of lithium carbonate in solar pond.

Experimental principle and analytical method

Experimental principle

The precipitation reaction of Li2CO3 can be expressed by the ionic equation: 2Li+ (aq) + CO32-(aq) ⇌ Li2CO3(s). Based on this equilibrium reaction, the solubility product constant Ksp(Li2CO3) can be calculated. The calculation expression is Ksp(Li2CO3) = [Li*]2 ∙ [CO32−], where [ ] symbolizes ionic activity, and ionic activity is approximately replaced by the ion concentration for the purpose of providing intuitive guidance on brine mixing operations in practical production. It can be argued that the relevant property is actually an apparent solubility constant, noted K* by Millero and Hawke18. In this paper, the solubility product constant Ksp(Li2CO3) is used as the criterion to characterize the favorable mixture composition.

The brine mixing method is to proportionally mix a certain amount of brine with low Li+ and high CO32− into the brine with high Li+ and low CO32−, and the mixed brine could be poured into the crystallization pond as the mother liquor for lithium extraction to make the SGSP for heating the brine up and precipitating the lithium salts. Due to the increase in CO32− concentration after brine mixing, the lithium carbonate could be crystallized more thoroughly from the brine, thereby improving the lithium yield and reducing the production cost, especially avoiding the impact and damage caused by the use of alkaline industrial precipitation agents on the natural environment of salt lake. Compared with other methods, the brine mixing method is economical and environmentally friendly, easier to operate and has outstanding effect. It is very suitable for the green and efficient extraction of lithium resources from carbonate-type salt lakes in areas with inconvenient transportation and relatively backward industrial energy conditions.

The brine mixing method includes the same-year brine mixing method and the cross-year brine mixing method. The same-year brine mixing method means that the raw material used for the brine mixing are from the same year. The winter tail brine discharged from the SGSP after lithium precipitation is mixed with the summer concentrated brine obtained by the evaporation process of the salt fields in a certain proportion and used as the mother liquor for lithium extraction. This method utilizes part of the residual heat from the winter tail brine and reduces the pressure of brine production. Compared with the same-year brine mixing method, the raw material used in the cross-year brine mixing method come from the two years before and after, and there is a winter interval. Before the rainy season (July to September every year), the summer brine produced by the evaporation and concentration of the salt fields is stored for overwintering in SGSP, and then mixed with the winter brine in a certain proportion in February and March of the next year as the mother liquor of lithium extraction. This method can not only increase the CO32− concentration and rate of lithium precipitation from brine, but also effectively utilize some of the heat accumulated in the lower convective zone of SGSP, alleviating the pressure of brine production to a certain extent. The flow chart of optimization process of lithium extraction from Zabuye salt lake combined with brine mixing method is shown in Fig. 3.

To be specific, the initial concentrations of Li+ and CO32− extracted from Zabuye salt lake in October each year are generally around 0.8 g/L and 30 g/L. After the natural evaporation and concentration in the multi-stage salt fields, part of it is made into the winter brine with high Li+ and low CO32− in February to March of the next year, in which the concentration of Li+ and CO32− in brine is about 2.2 g/L and 20 g/L. It is directly poured into the crystallization pond as the mother liquor for lithium extraction, and a layer of fresh water is laid on the surface of the brine to form a SGSP for heat accumulation and temperature rise to precipitate the lithium carbonate. The winter tail brine discharged after the salt collection is high in Li+ and low in CO32−, with the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− around 1.7 g/L and 20 g/L. Another part of the brine in the salt fields continues to undergo sun evaporation and concentration. Due to the gradual rise in temperature, it is made into the summer brine with low Li+ and high CO32− from July to September of the next year, in which the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− is about 1.2 g/L and 40 g/L. The SGSP can be used to store brine for overwintering, and the brine quality remains basically unchanged in February and March of the following year, with only a slight decrease in the concentrations of Li+ and CO32−. Then, by mixing it with the winter concentrated brine with high Li+ and low CO32− produced at that time and conducting the cross-year brine mixing operation in the brine mixing pond, a high-quality mother liquor for lithium extraction can be obtained. Further evaporation and concentration of the summer brine can produce the summer concentrated brine with low Li+ and high CO32−, in which the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− are as high as 1.6 g/L and 40 g/L or more. By mixing it with the winter tail brine discharged from the SGSP in the same year, the mother liquor suitable for the lithium deposition in the SGSP can also be obtained.

Analytical method

Relying on the Zabuye Salt Lake Resources and Environment Tibet Autonomous Region Field Scientific Observation and Research Station, the on-site temperature of mining area can be observed and recorded by the automatic meteorological observation instrument with an accuracy of ± 0.1 °C, and the brine density can be measured by the floating hydrometer with an accuracy of ± 0.001 g⋅cm−3. The weight of lithium mixed salt is weighed by the electronic scales with an accuracy of ± 0.01 g. The concentration of Li+ and CO32− in solid and liquid samples obtained during the experiment could be determined by the flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry and volumetric analysis, respectively19.

Experimental process and results discussion

The same-year brine mixing laboratory experiment

Experimental material

A same-year brine mixing experiment was carried out in the laboratory of Zabuye mining area on May 20, 2019. The physicochemical parameters of raw material brine used in the experiment are shown in Table 1.

Experimental process

According to the pre-set brine mixing ratio, different amounts of winter tail brine and summer concentrated brine were taken and mixed in a beaker to prepare a series of mixed solutions. The total volume of each mixed solution was controlled to be 3000 mL, so as to obtain enough salt crystals for laboratory analysis. After thoroughly stirring and mixing well, the mouth of the beaker was sealed with plastic film and placed in a thermostatic bath for water bath heating. The heating temperature was set at 40 °C. The heating operation started at 20:00 on May 21, 2019 and ended at 16:00 on May 23, 2019, with a total heating time of 44 h. During this period, the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− in the solution were continuously monitored. When the concentrations of the both remained relatively stable and no longer changed, it indicated that the solution had basically reached the equilibrium at this time, that is, the experiment was terminated. The solid–liquid separation of the heated solution was carried out by using the filtration equipment. The liquid samples were taken for chemical analysis. The solid samples were dried and weighed, and the contents of lithium carbonate were measured. Figure 4 shows the scene of the water bath heating in the same-year brine mixing laboratory experiment.

Experimental results and discussion

During the same-year brine mixing laboratory experiment, the test data and variations of Li+ and CO32- concentrations in brine before and after heating under different brine mixing ratios are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 5. The test data of the weight, grade and lithium yield of precipitated lithium mixed salt and their changes with the brine mixing ratio are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 6.

In this experiment, a decrease in the brine mixing ratio means that the proportion of winter tail brine is less and less, while the proportion of summer concentrated brine is more and more, resulting in a gradual decrease in Li+ concentration and a significant increase in CO32− concentration in brine after mixing. As can be seen from Fig. 5, after being sealed and heated at 40 °C until lithium carbonate was completely precipitated, the concentration of Li+ in brine decreased to a certain extent compared with that before heating, and the decreasing amplitude significantly increased with the decreasing of the brine mixing ratio, ranging from 0.02 g/L to 0.57 g/L. In comparison, the concentration of CO32− in brine after heating did not change much and decreased slightly. The results show that CO32− plays a decisive role in the saturated precipitation of lithium carbonate. When the concentrations of Li+ in brine are almost the same, the higher the concentration of CO32−, the larger the precipitation rate of lithium carbonate, and the better the crystallization effect.

From the experiments, the amount of lithium carbonate precipitated from brine varies with different brine mixing ratios. It can be seen from Table 3 and Fig. 6 that when the brine mixing ratio is 1:0, that is, the winter tail brine is directly sealed and heated at 40 °C without brine mixing, and there is almost no lithium mixed salt precipitated from the brine, indicating that the lithium carbonate in the winter tail brine used in the experiment has not reached saturation and crystallized throughout the entire heating process. As the continuous reduction of the brine mixing ratio decreases, that is, the amount of summer concentrated brine added increases, the weight of lithium mixed salt precipitated from the brine gradually increased, while the grade difference of lithium carbonate is not significant, ranging from 71.82% to 80.39%. The calculated lithium yield shows an increasing trend with the reduction of brine mixing ratio. When the brine mixing ratio is 1:1.25 or even lower, the weight of the precipitated lithium mixed salt significantly increases, and the yield of lithium carbonate is almost above 20%. Especially when the brine mixing ratio is reduced to 0:1, that is the summer concentrated brine is directly sealed and heated at 40 °C without brine mixing, the crystallization effect of lithium mixed salt is the best. The amount of converted pure lithium carbonate is the largest, and the yield of lithium carbonate is also the highest, reaching 30.18%. This is because the quality of summer concentrated brine used in the experiment is better. Although the concentration of Li+ is low, the concentration of CO32− is high. The lithium carbonate in brine has basically reached a saturated state, and can be crystallized once heated. On the contrary, the winter tail brine discharged from the solar pond after lithium extraction has a high concentration of Li+ and too low concentration of CO32−, and the lithium carbonate in brine is far from saturation. If it is directly sealed and heated without brine mixing, there is almost no lithium mixed salt precipitated, and the crystallization effect of lithium carbonate is the worst. This further indicates that the concentration of CO32− in brine has a significant impact on the crystallization effect of lithium carbonate. It is suggested that for the winter tail brine with high Li+ and low CO32− discharged from the solar pond after lithium extraction, a certain amount of the summer concentrated brine with low Li+ and high CO32− prepared from the salt field at the same period should be appropriately mixed with to regulate the concentration of CO32−, and the mixed liquid after brine mixing could be poured into the crystallization pond as the mother liquor for lithium extraction for recycling. In addition, it is necessary to pay attention to the brine production process in the salt field. The concentration of CO32− should be increased as much as possible while ensuring the high concentration of Li+ in the summer concentrated brine.

The cross-year brine mixing laboratory experiment

Experimental material

A cross-year brine mixing experiment was carried out in the laboratory of Zabuye mining area on May 5, 2020. The physicochemical parameters of the raw material brine used in the experiment are shown in Table 4.

Experimental process

Due to the fact that some salt crystals had already precipitated from the summer brine stored hermetically from August 2019 to May 2020, it needs to be heated to 20 °C for stirring and redissolution before the brine mixing operation. The summer brine were mixed evenly with the winter concentrated brine according to the preset brine mixing ratio, and then heated in a water bath at the temperature of 40 °C. The brine heating operation began at 12:00 on May 5, 2020 and lasted until 12:00 on May 8, 2020, with a total heating time of 72 h. When the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− in brine remained relatively stable and did not change, the experiment was terminated. The samples were analyzed and tested after the solid–liquid separation.

Experimental results and discussion

During the cross-year brine mixing laboratory experiment, the test data and variations of Li+ and CO32− concentrations in brine before and after heating under different brine mixing ratios and their changes are shown in Table 5 and Fig. 7. The test data of the weight, grade and lithium yield of precipitated lithium mixed salt and their changes with the brine mixing ratio are shown in Table 6 and Fig. 8.

As can be seen from Table 5 and Fig. 7, the concentration of Li+ in winter concentrated brine is higher, reaching 2.07 g/L, while that of CO32− is lower, only 25.04 g/L. The summer brine for mixing is just the opposite, with a lower concentration of Li+, only 1.19 g/L, and a higher concentration of CO32−, reaching 45.24 g/L. Although the concentration of Li+ in the original winter concentrated brine is slightly reduced after mixing with summer brine, the concentration of CO32− is significantly increased. After heating, both the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− decreased to varying degrees, indicating that a certain amount of lithium carbonate precipitated from the mixed brine under different brine mixing ratios.

The specific precipitation situation of lithium carbonate could be known from Table 6 and Fig. 8. Due to that the lithium carbonate in winter concentrated brine or summer brine is not saturated, the precipitation effect of lithium carbonate is not good when it is directly sealed and heated, and the lithium yield is only 16.10% and 10.00% respectively. When the winter concentrated brine and summer brine are mixed at the ratio of 1:0.5, the concentration of Li+ in the mixed brine is 1.78 g/L and that of CO32− is 31.77 g/L. The lithium precipitation effect of brine after heating is significant, and the lithium yield reaches 31.89%. Especially when the brine mixing ratio is 1:0.75, the concentration of Li+ is 1.69 g/L and that of CO32− is 33.68 g/L. At this time, the mixed brine has the best effect of lithium precipitation after heating, and the lithium yield can reach 34.44%. It can be seen that under the several brine mixing ratios investigated in the experiment, the precipitation amount of lithium carbonate in the mixed brine increases first and then decreases with the decrease of brine mixing ratio. Compared with winter concentrated brine or summer brine without mixing, the lithium yield has increased by 1.36 ~ 3.44 times, and the grade of lithium mixed salt is also above 70%. In addition, when the concentration of Li+ in the mixed brine is above 1.60 g/L and the concentration of CO32− is above 30 g/L, the lithium yield is relatively higher, which can reach more than 30%. The results show that both the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− are very important for the crystallization effect of lithium carbonate in brine, and the cross-year brine mixing method can significantly improve the precipitation amount and yield of lithium carbonate by increasing the concentration of CO32− in brine. Therefore, when pouring the winter concentrated brine into the crystallization pond at the beginning of each year, a certain amount of summer brine can be added to control the concentrations of Li+ and CO32− to be above 1.60 g/L and 30 g/L. That is, Ksp(Li2CO3) = 0.02645 is used as the criterion for characterizing the favorable mixture composition. Cheng et al.20 measured the solubility of Li2CO3 in Na–K–Li–Cl brines within the temperature range of 20 to 90 °C. According to the Ksp(T) equation proposed, Ksp(25°C) = 0.0012 and Ksp(40 °C) = 0.0007. Using the solubility line, the apparent solubility constant can be roughly estimated at 0.021 at 25 °C and 0.015 at 40 °C in pure water. There is a certain difference between the values in the literature and those obtained in this paper, which is mainly due to the following reasons: Firstly, the numerical results in Cheng et al.20 are the data of lithium carbonate in a single salt solution, and these values will vary greatly depending on the salinity of the brine and the nature of the electrolyte. The Pitzer ion-interaction model has been used to theoretically predict the osmotic coefficient and the activity coefficients of chemical species at different concentrations of electrolytes and different temperatures. As the research object of this paper, the Zabuye salt lake brine is a complex eight-element water-salt system, which differs greatly from the relatively simple single-salt system in the literature. Therefore, the numerical values in the literature have certain reference and guidance significance for this study. Secondly, unlike the experimental conditions set in the literature, the actual production process of the mining area will be affected by various factors, so the value calculated based on the measured ion concentration is an empirical value, which may be more intuitive and feasible for guiding the brine mixing operations. And then the mixed brine is poured into the crystallization pond as the mother liquor for lithium extraction, and a fresh water layer is laid to construct a SGSP for temperature rising and lithium precipitation. This allows for a higher lithium yield.

In addition, it is crucial to ensure the safe storage and overwintering of summer brine with low Li+ and high CO32- in the process of the cross-year brine mixing operation, which requires to prevent CO32− in summer brine from crystallizing out in the form of sodium carbonate in advance due to the decrease in ambient temperature of winter. The effective way is to keep the temperature of summer brine relatively stable. Theoretically, there will be no CO32− precipitation if the brine storage temperature is higher than that of summer brine. The SGSP in the production and operation of Zabuye mining area could precisely meet this requirement. It can not only provide a large amount of low-temperature heat energy at a lower cost, but also has a long-term heat storage capacity. At the same time, the characteristics of cross-season heat storage of SGSP make it highly attractive in cold regions, that is, storing the solar energy collected in summer and autumn for use in winter. It has also been pointed out in the literature that the existence of surface ice in winter is beneficial for the structure stability and winter insulation performance of the SGSP, and the overwintering operation has little effect on the chemical composition of the stored brine21,22,23,24. Therefore, after the end of lithium carbonate production in August or September every year, the summer brine with the concentration of CO32− generally around 50 g/L could be poured into the crystallization pond, and then a layer of fresh water is laid to construct a SGSP, which can store the summer brine for insulation and overwintering. When the crystallization pond needs to be filled with brine in February or March of the next year, the overwintered summer brine of a certain temperature with low Li+ and high CO32− can be used as a suitable raw material for mixing with the winter concentrated brine.

From the above two brine mixing methods, the implementation effect of the cross-year brine mixing method is significantly better than that of the same-year brine mixing method. In addition, the cross-year brine mixing method can not only significantly increase the yield and grade of lithium mixed salt, but also reduce the amount of the concentrated brine required for pouring into the crystallization pond, alleviating the pressure of brine preparation in salt fields to a certain extent. Meantime, due to that the overwintered summer brine has been in the lower troposphere of SGSP and accumulated a portion of heat, its temperature can generally reach 15°C or above. After mixed with the winter concentrated brine and poured into the crystallization pond, the initial temperature of brine in the lower troposphere of SGSP can be raised by at least 5°C, thus contributing to the improvement of the crystallization efficiency of lithium carbonate. To sum up, it is suggested that the SGSP technology coupled with the cross-year brine mixing method should be given priority in the production of lithium carbonate in Zabuye mining area.

The cross-year brine mixing production test

Test material

From February 25th to May 20th, 2022, a cross-year brine mixing production test has been carried out in the third operation area of the Zabuye mining area, lasting nearly three months. The physicochemical parameters of raw material brine and the brine after mixing used in the cross-year brine mixing production test are shown in Table 7. When the winter concentrated brine and the summer brine stored for overwintering were mixed evenly at the optimal ratio of 1:0.75, the temperature of the mixed brine was 6.0 °C, which was 13 °C higher than that of the winter concentrated brine. Although the concentration of Li+ in the mixed brine was reduced by 0.26 g/L compared with the winter concentrated brine, the CO32− concentration was increased by at least 5 g/L. These results indicate that the initial temperature and CO32− concentration of brine can be significantly increased by brine mixing operation.

Test process

The crystallization pond S10 was selected as the brine mixing test pond, and the crystallization pond S11 without brine mixing as the comparison test pond. Both of them have an area of 4000 m2 and a depth of 3.8 m approximately. By controlling the flow rates of the water bump for extracting the winter concentrated brine and the summer brine to 200 m3/h and 150 m3/h respectively, the brine mixing ratio could be maintained at 1:0.75. The two were converged at the brine delivery channel and gradually mixed evenly during the flow process before being poured into the crystallization pond. Figure 9 shows the scene of brine mixing in the brine delivery channel during the cross-year brine mixing production test. The stereo-crystallization process with solar pond was adopted in each test pond. The brine filling depth was about 2.40 m, and the thickness of fresh water layer was about 0.30 m. And then the SGSP was made and formed for heat accumulation and temperature raising to precipitate the lithium carbonate. The operation scene of test pond S10 during the cross-year brine mixing production test process could be seen from Fig. 10.

Test results and discussion

The systematic sampling before brine discharge was carried out in the test pond S10 and the comparison pond S11 on May 19, 2022. A series of samples were taken at the fixed sampling points of each pond according to the pre-set depths (i.e., the height from the bottom of the pond was 10 cm, 50 cm, 100 cm, 150 cm, 180 cm, 200 cm, 220 cm, 240 cm, 260 cm and 280 cm). The temperature, density, Li+ and CO32− concentrations of the liquid samples were measured respectively. Table 8 lists the observation data of the test pond S10 and the comparison pond S11 before brine discharge in the cross-year brine mixing production test. Figure 11 compares the changes of important parameters of the two ponds before brine discharge such as the brine temperature, density, and concentrations of Li+ and CO32- with the height from the bottom of the pond.

As can be seen from Fig. 11 and Table 9, although the initial brine temperature of the test pond S10 was 5°C higher than that of the comparison pond S11, with the formation of the salinity-gradient layer, the brine in the SGSP received solar radiation for a long time to heat up and gradually became stable in the later stage. The longitudinal distributions of brine temperature in the two ponds before brine discharge were basically the same, with the average brine temperature around 28.4°C, and that of the lower convective zone (LCZ) around 32°C. The temperature difference of the test pond S10 from brine irrigation to brine discharge was 22.5°C, while that of the comparison pond S11 was 27.3°C. The longitudinal distribution of brine density in both ponds before brine discharge was similar, only the comparison pond S11 was slightly lower than the test pond S10, which can be considered that the salt minerals have been completely precipitated from the brine in the two ponds and reached the equilibrium state. Meanwhile, the longitudinal distributions of Li+ and CO32- concentrations in the brine of two ponds were also similar, but the concentration of Li+ in the LCZ of the test pond S10 was lower than that of the comparison pond S11, and the concentration of CO32- was significantly higher. From brine irrigation to brine drainage, the change in concentration of Li+ in the brine of the two ponds had little difference, ranging from 0.7 g/L to 0.8 g/L, while that of CO32- had a relatively large difference. The concentration of CO32- in the test pond S10 changed up to 8.03 g/L, and that in the comparison pond S11 had a change of 6.91 g/L, indicating that the lithium carbonate was precipitated more completely from the brine of the test pond S10.

Figure 12 shows the actual crystallization effect of lithium carbonate in the test pond S10 after the brine has been discharged from the solar pond. It can be seen that lithium carbonate concentrate was deposited on the slope, bottom, and nucleation matrix inside the pond. The lithium mixed salt precipitated at different positions of the test pond S10 and the comparison pond S11 has been collected and weighed respectively. The recorded data are shown in Table 10, and the comparison of the actual yield increase effect of pure lithium carbonate in the cross-year brine mixing production test is drawn, as shown in Fig. 13.

When the concentration of Li+ in brine was above 2.00 g/L, the concentration of CO32- in brine poured into the test pond S10 was above 27.00 g/L, which was higher than that in winter concentrated brine poured into the comparison pond S11. At this time, Ksp(Li2CO3) is 0.0368, which is greater than the standard for characterizing the favorable mixture composition Ksp(Li2CO3) = 0.02645. As the concentration of CO32- in brine has a significant impact on the crystallization effect of lithium carbonate, Lithium carbonate has been precipitated from the brine of the test pond S10 more completely, which can be clearly seen from Fig. 13. The statistical data in Table 10 also showed that the lithium carbonate precipitated on the nucleation matrix, the bottom and the slope of the test pond S10 has increased to varying degrees compared with that of the comparison pond S11. The total weight of pure lithium carbonate in the test pond S10 was 19.75 t, which is 3.04 t more than that in the comparison pond S11, and the yield increase ratio reached 18.2%. The results indicated that the production of lithium carbonate in a single solar pond can be significantly increased based on the stereo-crystallization process of the solar pond combined with the cross-year brine mixing method.

Conclusion

New energy vehicles require lithium batteries. Lithium carbonate, as the main raw material for power batteries, will continue to increase in demand with the rapid development of downstream new energy industries. China’s salt lakes are rich in lithium resources. Zabuye salt lake, located on the Tibet Plateau, known as the roof of the world, adopts the green technology of SGSPto extract the lithium carbonate from salt lake brine, which is a pioneer in lithium extraction from salt lakes in China and a powerful supplier of lithium resources. Due to the unsatisfactory quality and the insufficient amount of lithium-rich brine used to make the SGSP, the production and yield of the lithium concentrate in single solar pond has been seriously affected. It is concluded that the concentration of CO32- in lithium-rich brine is a very important influence factor for the precipitation of lithium carbonate in the SGSP, which is the same as that of Li+. The brine mixing method can cleverly utilize the advantages of different qualities of brine for regulation, thereby obtaining the best quality of lithium-rich brine that meets the conditions for making the SGSP. The research results show that the precipitation rate of lithium carbonate can be significantly improved by the cross-year brine mixing method, and the implementation effect is obviously better than that of the same-year brine mixing method. The winter concentrated brine with high Li+ and low CO32- should be mixed with the summer brine stored for overwintering with low Li+ and high CO32- to ensure that the concentration of CO32- is as high as possible under the condition of higher Li+ concentration. The resulting mixed brine could be used as the mother liquor for lithium extraction. This will not only increases the yield and grade of lithium concentrate in a single solar pond, but also reduces the dosage of the winter concentrated brine and the pressure of brine production in the previous procedure. Under the circumstance of greater environmental protection pressure and the serious shortage of salt field area, it is recommended that on the basis of the traditional "lithium extraction technology with SGSP", the stereo-crystallization process of solar pond coupled with the cross-year brine mixing method can be given priority to the production of lithium carbonate in Zabuye mining area, which is conducive to the green and efficient extraction of lithium resources in salt lakes on the Tibet Plateau.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SGSP:

-

Salinity-gradient solar pond

- UCZ:

-

Upper convective zone

- NCZ:

-

Non-convective zone

- LCZ:

-

Lower convective zone

- HDPE:

-

High-density polyethylene

- C x :

-

Concentration of x ion in brine (g/L)

- Cb x :

-

Concentration of x ion in brine before heating after brine mixing (g/L)

- Ca x :

-

Concentration of x ion in brine after heating (g/L)

- T b :

-

Brine temperature (°C)

- R :

-

Brine mixing ratio

- W LC :

-

Weight of lithium mixed salt

- W pLC :

-

Weight of pure lithium carbonate

- △W pLC :

-

Weight increase of pure lithium carbonate

- △wt :

-

Weight increase percent of pure lithium carbonate (%)

- G LC :

-

Grade of lithium mixed salt (%)

- Y LC :

-

Yield of lithium carbonate (%)

- ρ b :

-

Brine density (g/cm3)

- d p :

-

Height from the bottom of the solar pond (cm)

- W pLC nm :

-

Weight of pure lithium carbonate on the nucleation matrix (t)

- W pLC bp :

-

Weight of pure lithium carbonate at the bottom of pond (t)

- W pLC sp :

-

Weight of pure lithium carbonate on the slope of pond (t)

- T b, max :

-

Maximum brine temperature (°C)

- T b, av :

-

Average brine temperature (°C)

- T b, avL :

-

Average brine temperature in the LCZ (°C)

- △T b :

-

Brine temperature change from brine irrigation to brine drainage (°C)

- C x , av :

-

Average concentration of x ion in brine (g/L)

- C x , maxL :

-

Maximum concentration of x ion in brine of the LCZ (g/L)

- C x , minL :

-

Minimum concentration of x ion in brine of the LCZ (g/L)

- △C x :

-

Concentration change of x ion in brine from brine irrigation to brine drainage (g/L)

- Ksp(Li2CO3):

-

Solubility product constant of lithium carbonate

- [x] :

-

Ionic activity of x ion which is replaced by ion concentration

References

Ferrari, S. et al. Solid-state post Li metal ion batteries: A sustainable forthcoming reality?. Adv. Energy Mater. 11(43), 2100785 (2021).

Liu, Y. B., Ma, B. Z., Lv, Y. W., Wang, C. Y. & Chen, Y. Q. Thorough extraction of lithium and rubidium from lepidolite via thermal activation and acid leaching. Miner. Eng. 178, 107407 (2022).

U.S. Geological Survey. Mineral Commodity Summaries 2022. U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.3133/mcs2022 (2022).

Goto, M. et al. Nuclear and thermal feasibility of lithium-loaded high temperature gas-cooled reactor for tritium production for fusion reactors. Fusion Eng. Des. 136, 357–361 (2018).

Kesler, S. E. et al. Global lithium resources: Relative importance of pegmatite, brine and other deposits. Ore Geol. Rev. 48, 55–69 (2012).

Wang, Q. et al. Recent advances in magnesium/lithium separation and lithium extraction technologies from salt lake brine with high magnesium/lithium ratio. CIESC J. 72(6), 2905–2921 (2021).

Zhang, C., Lu, H.Y., Fei, P.F., Yang, L.R. Development Trend of Global Research in the Field of Lithium Extraction from Salt Lake Brine. J. Salt Lake Res. https://link.cnki.net/urlid/63.1026.P.20230920.1607.002 (2023).

Valyashko, M. G. Basic chemical types of natural waters and the conditions producing them. Records Acad. USSR 102, 315–318 (1955).

Liu, G., Zhao, Z. W. & Ghahreman, A. Novel approaches for lithium extraction from salt-lake brines: A review. Hydrometallurgy 187, 81–100 (2019).

Liu, Y. B., Ma, B. Z., Lv, Y. W., Wang, C. Y. & Chen, Y. Q. A review of lithium extraction from natural resources. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 30(2), 209–224 (2023).

Nie, Z. et al. Research progress on industrialization technology of lithium extraction from salt lake brine in China. Inorg. Chem. Ind. 54(10), 1–12 (2022).

Xu, S. S. et al. Extraction of lithium from Chinese salt-lake brines by membranes: Design and practice. J. Membr. Sci. 635, 119441 (2021).

Wang, Y. S., Zheng, M. P., Yan, L. J., Bu, L. Z. & Qi, W. Influence of the regional climate variations on lake changes of Zabuye, Dangqiong Co and Bankog Co salt lakes in Tibet. J. Geogr. Sci. 29(11), 1895–1907 (2019).

Ding, T. et al. Impact of regional climate change on the development of lithium resources in Zabuye salt lake, Tibet. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 865158 (2022).

Wu, Q. et al. The application of an enhanced salinity-gradient solar pond with nucleation matrix in lithium extraction from Zabuye salt lake in Tibet. Solar Energy 244, 104–114 (2022).

Wu, Q. et al. Study of the optimization of the stereo-crystallization process with enhanced salinity-gradient solar pond for lithium extraction from Zabuye salt lake in Tibet. Carbonates Evaporites 39, 10 (2024).

Yu, J. J. et al. Experimental study on improving lithium extraction efficiency of salinity-gradient solar pond through sodium carbonate addition and agitation. Solar Energy 242, 364–377 (2022).

Millero, F. J. & Hawke, D. J. Ionic interactions of divalent metals in natural waters. Mar. Chem. 40(1–2), 19–48 (1992).

Qinghai Institute of Salt Lakes, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Analysis Methods for Brines and Salts (Second Edition). (Science Press, 1988).

Cheng, W., Li, Z. & Cheng, F. Solubility of Li2CO3 in Na–K–Li–Cl brines from 20 to 90 °C. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 67, 74–82 (2013).

Atkinson, J. F. Effect of surface ice on solar pond performance. Solar Energy 45(4), 207–214 (1990).

Bryant, H. C. & Colbeck, I. A solar pond for London. Solar Energy 19(3), 321–322 (1977).

Li, N. Water Object Study of Salt Gradient Solar Pond and Effect of Surface Ice on Solar Pond Performance (Dalian University of Technology, 2010).

Lund, P. D. & Routti, J. T. Feasibility of solar pond heating for northern cold climates. Solar Energy 33(2), 209–215 (1984).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20148, U21A2017), the Science and Technology Plan Projects of Tibet Autonomous Region (XZ202401JD0020) and the Enterprise Horizontal Scientific Research Project (HE2124, HE2316) for their funding. The author thanks Tibet Mining Asset Management Co. Ltd and Zabuye Salt Lake Resources and Environment Tibet Autonomous Region Field Scientific Observation and Research Station for providing access to the test site and convenient conditions under which this work was conducted.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Q. and Y.J. wrote the main manuscript text. Z.J. and Z.K. provided the experimental materials and coordinated the experimental conditions. L.J. and S.D. collected and organized the experimental data. B.L., H.Z. and W.Q. conducted the experimental research. N.Z. and B.L. prepared Figs. 1–10 and provided the research funding support. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Q., Yu, J., Zhang, J. et al. Study on the application of brine mixing method in lithium extraction from Zabuye salt lake, Tibet. Sci Rep 15, 2846 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86425-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86425-w