Abstract

High costs and project-based (short-term) financing mean that coastal engineering projects are often undertaken in the absence of appropriate post-construction monitoring programmes. Consequently, the performance of shoreline-stabilizing structures or beach nourishments cannot be properly quantified. Given the high value of beaches and the increase in erosion problems and coastal engineering responses, managers require as much accurate data as possible to support efficient decision-making. This work presents a methodological approach to characterise coastline position changes as a result of engineering actions. We describe a new, low-cost method based on satellite remote sensing to monitor shoreline evolution at high temporal and spatial resolution pre-, during and post-implementation. Initially, satellite-derived waterlines are identified and extracted from publicly available satellite imagery of the Landsat 5, 7, 8, and 9, and Sentinel-2 constellations using the automatic shoreline extraction tool SHOREX. The waterline positions are then compiled, differences over time are quantified, and a matrix is constructed that allows easy depiction and interpretation of spatial and temporal patterns of erosion/accretion. This allows the access and the comprehension of the morphological data by the non-expert. Two examples of application on the Valencian coast of Spain at different spatial scales demonstrate how beach response to coastal engineering actions can be characterised at different levels of detail (from local to regional) and over different periods of time. These applications evidence the utility of the approach as it allows analysis of pre- and post-intervention coastal change and offers a means to overcome the widespread lack of monitoring and hence to improve coastal engineering practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Beaches are a key natural and socio-economic resource of coastal environments worldwide1,2,3. The recreational use of beaches is the core of a global tourism sector based on sun, sea and sand4,5. As a result, many beaches are backed by dense tourism-related infrastructure, which are at risk from coastal change, especially during storms6,7.

Climate change is modifying hydrodynamics and elevating sea levels, which are resulting in increased rates and extent of erosion and increased risk on developed shorelines8,9,10. The important socioeconomic role of beaches means that their degradation or potential loss raises considerable concerns among the public, governmental bodies, businesses, and stakeholders11,12. A common response to the threat of erosion or flooding is to implement beach nourishments with the aim to stabilise or advance the shoreline and thereby sustaining the tourism economy and protect infrastructure13,14. However, to maintain beaches using nourishment may present complex and negative implications15, and it may require repeated interventions and monitoring to guide their location and timing.

Lack of information on coastal change is a major impediment in coastal management decision-making16. This is compounded by the fact that most engineering interventions are undertaken on a project basis and seldom involve pre- or post- project monitoring. In a few cases (e.g. Netherlands17, Gold Coast of Australia18, Oregon and Washington (USA)19, southwest France20, southeast England21) are observations of coastal change carried out at the regional scale with high spatiotemporal resolution. This lack of observations makes it impossible to assess the regional scale and long-term impact of interventions. The limited monitoring is partly due to expense and resource-commitment associated with commonly used techniques such as topographic profiles22.

In this respect, remote approaches based on satellite imagery offer an important source of information for monitoring coastal morphology, overcoming the drawbacks of traditional methods23,24. Successive multispectral images from the Landsat and Sentinel-2 optical satellite constellations constitute routinely sampled and publicly accessible optical imagery covering the whole planet over several decades25. An important advantage of these images is the systematic recording with a high temporal frequency (every 2 to 5 days when images from different satellites are combined). The possibility to freely access the optical satellite imagery has opened up a new scenario for the efficient characterisation of coastal spaces and beach dynamism26. The water/land boundary and beach width are parameters/indicators that can be readily derived from such imagery and are useful for describing the physical state of the beach in a consistent way27,28.

Several algorithmic solutions have recently been proposed to deduce the position of the coastline with sub-pixel accuracy (better than pixel size) from optical data (see review in29). Among them, diverse stand-alone extraction tools have been developed encompassing all the necessary steps from data acquisition to the definition of the waterline position (see benchmarking in30) from satellite imagery, i.e., the satellite-derived waterline (SDWL). Based on the subpixel solution proposed in31, the shoreline analysis and extration tool (SAET)32 and the automatic shoreline extraction tool SHOREX33,34 represent new, efficient ways to extract SDWLs over long periods (decades) and distances with sufficient accuracy to describe the morphological changes at different time scales on the beaches. Managing and analysing large waterline datasets, however, poses important challenges for the final users of this information.

Although tools such as the digital shoreline analysis system (DSAS)35 were designed to deal with such data, they may present performance limitations as they are tools incorporated to GIS software restricted to transect-based analysis36. As an alternative, we advocate the method based on spatial-temporal models of the beach width and its changes over time and space (proposed in37) to enable a matrix-based holistic vision of beach changes throughout a sedimentary cell. This technique allows the visualization of the response of a given intervention in the adjacent area and throughout the sediment cell. The interconnections can be visualised and the real impact (and success or failure) of each intervention can be assessed.

Based on remote sensing techniques leading to an easily accessible depiction of spatio-temporal shoreline change, this work presents a new methodological approach for the continuous monitoring of the morphological effects of coastal engineering projects worldwide. Two applications from the Valencian coast of Spain are used to illustrate the utility of the approach at local and regional scales.

Methodological approach

Definition of satellite-derived waterlines

The approach is based on the definition of SDWLs from the optical satellite images of equivalent pixel size acquired by the Sentinel-2 (S2) and Landsat 5, 7, 8 and 9 satellites (Fig. 1). The images (20–30 m pixel size respectively for the near-infrared bands) are available free of charge from the Copernicus Data Space Ecosystem (CDSE, https://dataspace.copernicus.eu) for the case of the S2, and the Earth Explorer of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS, https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/) for the case of the Landsat series, offering information from 1984 to the present.

The process of downloading, pre-processing, spatial georeferencing enhancement and subpixel definition was performed using the stand-alone python toolkit SHOREX33,34 developed within the Geo-Environmental Cartography and Remote Sensing Group (http://cgat.webs.upv.es/). Although SHOREX and SAET could be used interchangeably, SHOREX was chosen for this work as it constitutes the most efficient solution for multi-decadal analyses. The core of the system is a sub-pixel automatic SDWL extraction algorithm described a decade ago31 but subsequently improved, gaining accuracy and efficiency. Subsequently, the extraction workflow follows four main phases: downloading of the images; cloud filtering, subpixel georeferencing, creation of water indices for water/land classification; and finally, SDWL extraction at subpixel level (for more details see33,34).

These instantaneous SDWLs are defined as the water/land intersection at the acquisition time of each image, and they were constituted by points located every 5 m (S2 imagery) and 7.5 m (Landsat). In order to validate the employment of the resulting waterline for coastal monitoring purposes, robust accuracy assessments have been carried out (Table 1). Thus, the accuracy of 91 SDWLs obtained at cala millor beach (Mallorca) using SHOREX was evaluated considering reference lines from a video monitoring system38. The root mean square error (RMSE) of the instantaneous SDWLs obtained from S2 images was 3.01 m and 3.59 m for Landsat 8. The results obtained on different coastal types appear on the same order of magnitude (Table 1), and indicate that dissipative beaches, more prone to present complex intertidal morphologies and water-saturated sands may pose a challenge when identifying the waterline position and lead to lower accuracies. In any case, both extraction tools as well as others designed with the same aim are capable of offering accuracy levels high enough to characterise erosion and recovery trends (see benchmarking in30).

The SDWL position obtained with these algorithms is dependent on the total water level elevation, which is defined by the instantaneous waves and tide conditions in combination with the beach morphology42,43. The shoreline positions can be obtained by referencing the SDWL positions to a single reference elevation datum enabling a more robust analysis of changes over time23. However, due to the limited total water level variations occurring on microtidal and low energetic coasts, the waterline and the shoreline position can be assimilated (hence the terms SDWL and SDS).

Spatial-temporal characterisation of beach width and shoreline changes

The information provided by the SDWLs can be arranged to enable further analysis. Spatial-temporal models (STMs) of the shoreline changes can be obtained by following the methodology described in37. Thus, beach widths are defined as the distance between the points that constitute the SDWLs and the inner edge of the beach (Fig. 2A) previously photointerpreted on a high-resolution orthophoto. The inner line of the beach is defined by photointerpretation of an aerial photograph, and the distance to the points defining each SDWL was measured (see Fig. 2B). All the obtained measurements are organised in space and time in order to overcome the unequal distribution of records and to have homogeneously available data throughout the site and the period analysed. Those measurements are used to deduce a continuum of values for times and locations that lack real measurement by applying a triangulated irregular network (TIN) interpolation and a rasterisation of the results to generate the STM (see Fig. 2C). This model consists of a Hovmöller-style diagram with the values of the shoreline changes organised in cells for time and space37. This overcomes the unequal distribution of records and renders homogenous data for the whole study site and period.

(A) Measurements of the distance between the points composing the SDWLs and the reference baseline, and the definition of the average distance for each date and baseline segment; (B) Organisation of the measurements over time and along the coast; and (C) the transformation of the discrete information into continuous STMs by interpolation, allowing the visualization of beach changes over time, or the alongshore characterisation of the shoreline position at any given time.

Analysis of beach width and shoreline changes on specific dates or sites

The analysis of the resulting STMs allows the derivation of temporal plots of shoreline changes broken down into profiles, beaches or sectors of interest to the user (Fig. 2C). This type of analysis enables the end-user to obtain a quantification of the shoreline changes over time at any location (profile a,b), enabling the identification of various responses to the engineering actions. It is also possible to define the beach width on any given day throughout the whole study area (profile c,d), and, for example, the narrowest beach sectors can be easily identified.

In addition, following the same spatial-temporal style of data organisation, a new diagram can be derived by summarising the information in cells of any desired size. This can be accomplished by averaging the beach width for certain periods of time (i.e., annual, seasonal, etc.) and coastal lengths, thus providing another mode of presentation for the shoreline information.

Illustrative results

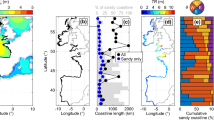

To demonstrate the utility and potential of the approach, this work presents two examples of applications from the Valencian coast of Spain (Fig. 3). This is a paradigmatic example of a developed sandy coastline experiencing erosion problems typical of such coasts. Heavy human pressure is evident in both urban development and artificialisation of the coastline because of actions carried out on and around the beaches. The two examples cover (a) at local scale, Ponent Beach in Benidorm (presented below in Sect. 3.1), and (b) at regional scale, the sector Valencia-Cullera, immediately south of the city and Port (Sect. 3.2). The application in Benidorm focuses on a beach nourishment project to widen the beach in support of the tourism industry. The analysis of the Valencia-Cullera beaches presents the application of the remote approach at the regional scale (ca. 20 km alongshore distance), characterising an erosive problem with multiple causes addressed by multiple engineering actions.

Map of the Valencian coast showing location and setting of the two exemplar applications: (a) the Valencia-Cullera segment, and (b) Ponent Beach in Benidorm. The Valencia-Cullera sector is a semi-enclosed sediment cell between Port of Valencia and Cape of Cullera which is a sub-section of the ancient sedimentary cell comprising the whole Gulf of Valencia. The Benidorm beaches are discrete headland-embayment systems.

Local scale application: Ponent Beach, Benidorm

This example involves a spatially and temporally detailed investigation of a single sand nourishment with local-scale effects.

Description of the site and coastal engineering actions

The Benidorm coast comprises two microtidal sandy beaches (Ponent Beach and Llevant Beach) that face south and are confined by prominent rocky headlands (Fig. 3b). They are thereby protected from the dominant east-northeast waves44, while the Island of Benidorm modifies any swell approaching from the south. Most of the natural beach sediment was derived from nearby ravines45. Platja de Ponent Beach is a 3100 m-long crescentic sandy beach delimited by rocky cliffs (Fig. 4). The Ponent Beach is isolated from the neighbouring Llevant Beach and there is almost no longshore transport into this coastal sector46.

Benidorm is a classic example of high-density, high-rise coastal tourism development47,48. It receives 2.4 million tourists per year49 based almost entirely on the recreational use of its beaches. Urbanization during and since the 1960s, involved an expansion of impermeable surfaces and canalization of ravines. These actions, along with the construction of maritime infrastructure, have led to a reduction in sediment supply to beaches and an erosion problem46.

In 1991 a large beach nourishment was carried out on Ponent Beach with the aim of sustaining the developing tourist industry. A total of 710,847 m3 of sand was dredged from the seabed and deposited on the eastern part of the beach50. A breakwater was constructed on the easternmost end of the beach51. The sand volume translated into more than 500 m3 per linear meter, leading to a width increment of about 70 m in the easternmost area46. The nourished sand was slightly coarser than the native sand. D50 increased from 0.22 mm in 1990 (just before the nourishment) to 0.301 mm in 201251.

Response of Ponent Beach to coastal engineering actions: analysis and interpretation of the morphological changes

After discarding those affected by the cloud coverage, 521 images acquired between 25/05/1984 and 30/01/2023 were processed to define the instantaneous waterline at the acquisition time (Fig. 5).

Analysis of the STM shows an abrupt widening of the beach in response to the 1991 beach nourishment (Fig. 6). The STM allows the derivation of spatial and temporal profile plots of the beach width changes (Fig. 7). The greatest widening took place in 1991 during and after the nourishment project, from 37.6 m (22/02/91) to 80.8 m (13/05/91). In the subsequent 12 months there was some shoreline recession, although the beach remained wider than before the action. The shoreline trend pre-nourishment (between 25/05/1985 and 22/02/91) was −0.41 m/year while the post-nourishment trend (between 27/04/1991 and 30/01/2023) was −0.13 m/year. When considering Ponent Beach as a whole, 1991 was not the period of maximum width along the series. In 2012 the beach width reached a maximum of 75 m (Fig. 7A), probably linked to changes in wave conditions.

STM of beach width changes (m) relative to 1984 in Ponent Beach (May 1984-January 2023). Zones A-E are identified in (Fig. 4).

Evolution of the (A) average width at Ponent Beach and (B) at zones A-E (see Fig. 4).

The STM also enables the quantification of the responses to the nourishment to be broken down into five zones (Fig. 7). The easternmost part of the beach (zone E) followed an erosive trend before the nourishment, leading to a minimum width of 11.8 m on 13/07/1990. The widening linked to the engineering action was most pronounced in the eastern half of the beach (zones D and E) while towards the west the widening was progressively less, and almost non-existent in zone A. After the beach nourishment, the pre-engineering shoreline behaviour was resumed. Thus, after the nourishment the eastern part (zones D, E) followed an erosive trend, while zones A and B maintained a positive trend (Table 2). The rates of change, however, in most cases (except in zone B) have smoothed slightly. However, it is remarkable that the different sectors (with the exception of C) present more robust trends (expressed by R2 values), after the nourishment action.

The propensity for change is highest at the ends of the beach, while the central part (zone C) remains basically stable, as was the case before nourishment. However, as in the pre-nourishment situation, the easternmost sections exhibited fluctuating periods of fast erosion compared to the steady cumulative erosion in the west. The graphic (Fig. 6) shows that the nourished sand has remained in the system but has moved progressively westward, in line with previous observations46. The detailed behaviour of the shoreline reveals slight progressive phases in zone E (note the average width of the beach between 2008 and 2016) within an overall erosive regime while slightly erosive phases occur in zone A in the 1995–2000, 2007–2011 and 2013–2017 periods (see Fig. 7).

These results show that the beach evolution reflects persistent structural or permanent factors, which implies that in the medium term the eastern zone will require additional contributions in order to maintain its width. This characteristic could be a key factor in designing future nourishment policies.

Regional case study: Port of Valencia-Cape Cullera segment

Description of the site and human actions in this littoral cell

This application focuses on a 28 km coastal stretch that extends from the Port of Valencia to Cape Cullera (Fig. 3a, Fig. 8).

Study site between the Port of valencia and cape cullera (orange colour) divided into 32 sections for analysis. Local beach names are shown in white and inlets linking L’Albufera Lake with the sea are in purple. The red polygons define the municipalities, among which Valencia, Sueca and Cullera occupy the coastline. The location of two sites characterised in detail in the figures below is identified by blue triangles.

This coastal segment is characterised by a microtidal coast with a tidal range of 0.24 m and a wave regime mainly defined by low-energy waves, with an average significant wave height of 0.7 m and a mean peak period of 4.2 s, as reported in37. However, during storms, waves of significant size can be recorded. The largest waves primarily come from the first quadrant, especially from the east-northeast orientation, and to a lesser extent from the northeast52.

The coastal segment is part of the ancient larger sedimentary cell that historically comprised the entire Gulf of Valencia (from the Ebro Delta in the North to Cape Sant Antoni53. The entire stretch is composed of fine to medium-sized sandy beaches44. The orientation of the coast in relation to the wave regime results in strong longshore sediment transport towards the south. The sedimentary cell under consideration here is delimited in the north by the Port of Valencia, which by the middle of the twentieth century was already a total barrier to the southward movement of sediments. The southern limit of the cell is the Cape of Cullera, a limestone promontory that slows the southward sand drift, resulting in deposition in the beach barrier that encloses the Albufera de Valencia Lake53. The Cullera Cape does experience occasional sediment bypassing44.

The coastal sector’s evolution is significantly influenced by reduced sediment inputs, particularly from the Túria River basin, due to sediment retention by 20th-century dam constructions. Substantial sediment retention (6.66 hm3 in the Benagéber reservoir and 0.8 hm3 in the Buseo reservoir) has been recorded in the Túria River basin54. While not all of these sediments are sand, their impoundment has considerably reduced the supply of sediment to the beach.

The Port of Valencia has undergone numerous changes in configuration55 which has modified wave action on the surrounding beaches. The port began to be built at the end of the eighteenth century and has been progressively enlarged. By the middle of the twentieth century, it was already a total barrier to the passage of sediments (Fig. 9A). During 1992–93 the southern dock was constructed (Fig. 9B). In 2005 the northern docks were modified (leading to the construction of the marina associated with the America’s Cup 2007 sailing competition, Fig. 9C). In 2010 the dock in the NE was built, and since then the external appearance of the port has remained unchanged (Fig. 9D). The port not only blocks southward longshore sediment transport of sediments but has also altered the wave shadow zone (Fig. 9E).

Source: Landsat 5 imagery courtesy of USGS, and S2 image from Copernicus, showing false colour. Image E shows the shadow areas affecting the beaches on the south for 20 and 50º waves (blue and red respectively) created by the two largest port enlargements, and the average frequency of waves above and below 2 m on this coast according to Spanish Ports Authority (https://www.puertos.es/en-us). The groins of Pinedo Beach appear in (E) in the red-shaded shadow area.

Evolution of the Port of Valencia between 1984 and 2021 (A–D).

Although of smaller magnitude, several breakwaters were constructed in recent decades at the mouths of the Gola del Pujol Nou, Gola del Perellonet, Gola del Perelló inlets (see Fig. 8). These have also affected longshore sediment transport. Agricultural and urban development have altered adjacent coastal dunefields53. Since the 1980s, a series of actions have been undertaken to restore the natural environment (Table 3). These involved the artificial introduction of sediments directly onto the shoreline and into dunefields. Multiple sediment inputs during the study period total 2,131,174 m3 of sand. These nourishments have been unevenly distributed in time and space, although the quantity and magnitude of contributions is greatest in the north. The volume contributed significantly increased in the middle of the study period (1990 to 2010).

Response of the beaches to coastal engineering actions

For this analysis, all the Landsat and S2 free-of-cloud images available from May 1984 to November 2020 were selected (Fig. 10). The extraction process led to the definition of 1044 shorelines (465 derived from L5, 226 from L7, 187 from L8, and 166 from S2). Compiling these in a STM allows the individual and collective impact of the various interventions to be assessed (Fig. 11).

STM of the changes in beach width with respect to the average beach width in 1984. The annual beach width average was defined for the 32 sections of 900 m length composing the study site. All the beach width measurements (for each 60 m segment and 1040 analysed dates) were considered. Seaward (landward) shifts are shown in shades of blue (red). The distribution of artificial sand inputs is presented in time and space, differentiating between direct inputs to the beach and to the dunes.

Impact of enlargements of the Port of Valencia

Changes in shoreline position and beach width show the influence of the port and artificial sediment inputs on the morphology of the beaches (Fig. 11). Construction of the southern dock in 1992 triggered strong erosion in the northern part of the study site (Sects. 3 to “Local scale application: Ponent beach, Benidorm”). In contrast, the northern modifications (starting in 2005) had a very limited effect on beach width. Figure 11 shows how the southern extension of the port in 1992 coincides with a progressive acceleration of erosion and southward extension of the erosion zone (see also Fig. 12A).

Examples of analysis with the support of this remote approach: (A) Average beach width in 1985 and 2020 along the whole study area, (B) evolution of the width on Platja del Dosser Beach (section 32) during the period 1984–2020, and (C) Evolution of the shoreline position on Platja de la Garrofera Beach (section 8) during 1990. See Fig. 8 for locations of B and C.

With the extension of the southern dock, the first kilometre of beaches immediately to the south (section “Introduction”) lay within the shadow zone of the most energetic swells (from NE and ENE). This led to a large increase in beach width in section “Introduction” in the situation in 2020 compared to 1985 (Fig. 12A). South from this point (Sects. 2-“Local scale application: Ponent beach, Benidorm”) the sediment deficit was exacerbated, probably due to the migration of sand both northwards (due to E and SE swell) and southwards (NE swell). Up to 1993 there was a retreat of about 15 m, but from 1993 to 1998 the beaches in this section lost an additional 28 m. The rapid retreat between 1993 and 1998 can also be seen in Sects. 3 to “Illustrative results”, albeit to a lesser extent. South of section “Illustrative results”, the erosive effects started later and lasted longer. The rest of the study site also experienced important changes, with a predominance of retreat in the northern part. In recent years the erosion zone reached the beaches of La Punta (Sect. 15) and Perellonet (16). In these places it is no longer clear whether construction of the dock is the main cause or whether it is a consequence of the underlying erosive trend.

On the other hand, the northern enlargement of the port (2009–2010) does not show significant effects on the downdrift beaches. The retreat in 2010 seems to reflect the impact of the storms at the end of 2009 and after 2010, beach width recovered in all the stretches.

Impact of beach nourishments and dune restoration

In order to counteract shoreline retreat in the northern sector (section “Introduction”), during 1998 and 1999 beach nourishments of 83,000 m3 were carried out. At the same time, by the end of 2001 two cross-shore breakwaters were constructed south of this section (see Fig. 9E) to prevent southward migration of the sand. As a result, the beach width recovered and between 1998 and 2001 the south of Pinedo Beach (Sect. 2) registered an increase in width (see Fig. 11). However, between 2001 and 2002, almost 15 m were lost, probably due to the impact of two storms in November 2001. Subsequently this stretch remained practically stable until 2017, when it again suffered a slight setback, probably due to the effect of more storms.

The placement of artificial sand had little effect on beach width (Figs. 8, 9). The nourishment of 500,000 m3 of very fine sand at Platja dels Ferros and La Garrofera in the spring of 1990 caused a rapid widening of the beaches (reaching 100 m increments in certain segments, Fig. 12C), although a few months later its effect had already disappeared. The rest of the large inputs made no obvious impact on shoreline position. These actions were not performed on the beach but were designed to rebuild (or rather directly to build) dunes. However, they probably had a positive effect on the sedimentary cell as a whole. During the period when most of the major contributions for the reconstruction of dunes took place (1997–2008), there was a clear advance of the shore in the southern sections of the study area. This gain in width in the central and southern sector, which both previously and after presented erosive trends, can only be explained by the fact that it received an increase in sediment input. The artificial nourishments, and particularly the dune interventions have not led to a significant and lasting widening of the beaches where they were emplaced. However, they seem to have had a positive response downstream increasing the width of the emerged beach.

Coastal storms and sediment deficit

The approach advocated here also enables the assessment of natural processes, including storms on the shoreline change record. As an example, in 2000 and 2001, especially to the south of the Perellonet inlet, the shoreline advanced between 2.5 and 15 m, but following strong storms in November 2001, erosion predominated (with retreat between 7.5 and 30 m). This same pattern was repeated after storms at the end of 2009 and 2012, in January 2017 and, particularly, after the storms in the winter of 2019/20. In the latter winter, especially as a result of Storm Gloria, a generalised retreat occurred on the whole shoreline. The severity of retreat was attributed to the large number and high magnitude of these storms55. The sectors further south also showed a marked erosional trend. The negative trend at the southern end (Platja del Dosser, Sects. 31–32, Fig. 12B) has been highlighted55 as it affects a stretch that had been historically advancing updrift of the cape of Cullera which acts as a natural sediment trap53. While Sect. 32 (Platja del Dosser south) had a positive balance until 2013 (+ 14 m compared to 1984), it has since retreated at an accelerating rate. In 2017 it was already showing a negative trend compared to 1984, and in 2020 it showed a loss of more than 7 m. These results suggest a strong sediment deficit in the sector probably due to the combined effects of the port and the chronic decrease in fluvial sediment contributions. From all the above, it can be deduced that the sustainability of these beaches is jeopardised by anthropogenic actions and that individual nourishments have had little regional impact.

Discussion

Despite a generally erosive scenario on coastlines worldwide, few public administrations implement monitoring systems to record coastline changes. Similarly, efficient protocols for monitoring coastal engineering actions are poorly developed and inconsistently applied. In response to the erosion problems that affect many coasts, beach nourishment actions are projected to increase with growing associated costs and important economic and logistical challenges56. Experience has shown that often engineered interventions do not perform as predicted by modelling57,58,59 or other means of prediction. The occurrence of unanticipated effects can lead to further interventions or re-engineering of the shoreline60. The lack of monitoring is often a result of project-based financing whereby the engineered structure is built but no further provision is made for long-term post-emplacement monitoring. In many countries, large coastal engineering projects undergo an environmental impact assessment that may require post-project surveillance programmes. In most cases, however, monitoring is very limited. With a few notable exceptions regional or national authorities seldom have provision for routine coastal monitoring and the success or otherwise of engineered interventions is poorly known. Several studies have shown that the fate of nourished sand is not always known. Staudt et al.14 described several existing monitoring practices, usually based on topo-bathymetric profiles. Thus, in Denmark, Belgium or the Netherlands, an annual or twice-yearly control is carried out to verify the efficiency of the protection measures applied. In Spain, monitoring is only carried out in the case of large inputs where an Environmental Impact Assessment has identified monitoring as mandatory. In the case of the USA, there is usually an obligation to monitor interventions but without defining a fixed time pattern for its realisation, and often surveys are carried out only after major storms or hurricanes61.

This scenario highlights the needs of end users for techniques to understand the effects of these actions and evaluate their effectiveness not only in the area where the intervention takes place but also in the whole sediment cell. Impacts must also be monitored from a sufficiently long temporal perspective since, in many cases, sediment displacements are only detected several years after the intervention. This broadening of the spatial and temporal scale can be done efficiently and robustly with remote sensing techniques, as the results presented here have shown.

Advantages of this remote approach for coastal monitoring

Continuum monitoring is an important means by which the performance of an engineering intervention can be assessed. Based on remote sensing, the proposed approach has the capability to derive multiple, closely spaced shorelines, covering large coastal territories. When combining S2 and Landsat 8 and 9 optical satellites the approach offers a theoretical global median average revisit interval of 2.3 day62. The SDWL positions are defined with error levels in the order of magnitude (about 3 m in the Mediterranean, see38) comparable to the best available techniques (see benchmarking30). This accuracy is sufficiently high to accurately characterise erosion and recovery trends, and beach response in the short (days) and mid-term (months)63. The SDWLs provide a detailed and continuous view of the evolving beach width with a detailed spatial and temporal characterisation beyond the scope of traditional shoreline monitoring techniques.

The STMs enable the user to define temporal plots to quantify shoreline changes on individual profiles or sectors of interest. For example, the daily beach width at Ponent Beach in Benidorm and its different sectors could be assessed as a response to a nourishment action. The comparison of the evolution followed by different shoreline sectors and their shoreline change rates allows end-users to assess the effectiveness of the engineering action three decades later, and to identify a trend according to which the sediment displaces towards the western side of the beach. This trend could not have been detected if the monitoring of the site had been limited to two or three years. Furthermore, the beach width information contained on the STMs can be summarised in cells of any desired size to create easily comprehensible diagrams. The resulting matrix of coastline and beach width changes constitutes an accessible way to understand and analyse the morphological data, even for non-specialist end-users (see Fig. 11). In addition, it is also possible to quantify the beach width on any given day of the historical series throughout the whole study area. The easy identification of the narrowest beach segments (Fig. 12B) is of interest in regions with a highly developed sun, sea and sand tourism industry as in the case in the Mediterranean and Caribbean coasts or the North American coasts of Florida, North and South Carolina or California, among others, for which the existence of narrow sections may condition the management and recreational usage of the beach (e.g.64,65,66).

Our remote approach contributes to the investigation of causal relationships including human actions and changing oceanographic dynamics. As can be seen in the two cases analysed, the remote approach offers the required holistic vision and permits a multi-scale analysis that allows a clear insight on how the coastal system has responded to human actions. In the case of Benidorm, a significant nourishment action determined the subsequent evolution of the coastal segment. The beach response can be clearly identified and remains over decades, leading to significant increases in beach width. This is especially marked in the eastern zone, alleviating its erosive problems. Nevertheless, after the nourishment the erosive trend was maintained in the eastern zone, reflecting the existence of permanent factors and implying that future nourishments will be required. In the case of the beaches south of Valencia, coexisting effects associated with the impact of the Port of Valencia, several nourishment actions, and cross-shore obstacles to longshore drift, together modify the coastline shape. The proposed remote approach quantified the progressive acceleration and extension of the erosion towards the south coinciding with the southern extension of the Port of Valencia in 1992. Since then, the sediment distribution was completely altered, jeopardising the sustainability of the beaches in the sector.

The analysis of the effects of sand inputs also allowed us to observe how the inputs would have a positive impact on the coastal system, although not necessarily where erosion problems are most severe. The proposed analysis identifies the medium-term usefulness of nourishment actions, which represent a new input of sediment into the coastal littoral system. Discharges onto the dune system rather than onto the beach itself appear to be an effective and useful measure to nourish the system as a whole with sediment. The sediment may drift and end up having a positive impact where the conditions of the beach profile have allowed the retention of sediment, in different parts of the coastal cell than where the nourishment actions were carried out. While they have not led to a significant and lasting widening of the beaches where they were emplaced, they seem to benefit the ‘sediment health’ of the whole sediment cell.

Landsat and S2 optical satellite imagery constitutes a suitable cost-effective approach for obtaining morphological information to monitor the coast. These constellations are framed in long-term data acquisition USGS and ESA projects, which assure the acquisition of images as a publicly available resource in the future67. Starting in 1984 (Landsat 5 images), this database presents a high degree of homogeneity, which allows for the development of systematic and automated analysis processes. This can constitute a key characteristic when considering its adoption by public administrations for monitoring at local, national or regional scale. The low cost is especially interesting for monitoring the coasts in developing countries where traditional and ground-based surveying methodologies are not feasible due to limitations associated with data inconsistency, inaccessibility or impossibility to deal with the costs68. In turn, retrospective studies can provide feedback and increase the understanding of the impact of coastal engineering actions, which can aid future planning. The availability of multidecadal series of shoreline data over sedimentary cells enables the robust detection of cumulative or erosional trends, offers a better understanding of the influence of climatic events69,70 and provides support to diagnose the present sedimentary state of beaches71.

Our approach offers a continuum of data over time and space, that contrasts with studies sustained on more traditional techniques such as topo-bathymetric profile surveying72,73,74 the photointerpretation of aerial photos75, light detection and ranging (LiDAR) surveying76, or videomonitoring techniques77. When there is a clear relationship between the artificial action and the morphological response beaches can be monitored using those techniques (e.g., by photointerpreting aerial photographs in Benidorm46). However, those sources of punctual information have important information gaps, both spatially and temporary, between measurements. When multiple interventions and disruptive events are involved (as in the case of the Valencia-Cullera sector), more detailed datasets are needed.

Adaptations to diverse coastal characteristics, limitations, and complementarity with other data sources

SAET and SHOREX extraction tools32,33 are both efficient solutions for the definition of the SDWL position, offering a level of accuracy in a broad typology of coasts comparable to the most accurate extraction tools (see30). Although they may be used interchangeably, each one presents advantages and drawbacks. Thus, SHOREX constitutes the best option for long-term studies with low magnitudes of error in multiple coastal types, ranging from ≈3 m RMSE in microtidal coasts to ≈5 m RMSE in tidal and exposed coasts38,40. In contrast, SAET may be the most efficient option for a preliminary assessment of the beach’s response to engineering actions and disruptive events. Although originally designed for monitoring the immediate effects of coastal storms63, it may enable efficient rapid mapping at regional scale of the effects of engineering actions. Its application may be more convenient in regions with no availability of auxiliary data (e.g. orthophotographs) to support the georeferencing process required by SHOREX, still offering a comparable level of errors in a broad variety of coastal types41.

With respect to coastlines with high tidal range and more wave energy, the variability of the water level associated with the acquisition of each satellite image may constitute an important source of errors in the resulting SDWLs therefore reducing their representativity when describing coastline changes43,78. In those environments consensus exists on the need for a horizontal correction based on instantaneous tidal conditions. This would lead to the transformation of SDWLs into datum-based SDSs relative to a single reference elevation datum to allow more robust definition of erosion and accretion trends24. Nevertheless, at this point there is still uncertainty about the role of run-up and swash in the definition of SDWL42, and more research is needed to efficiently estimate and compute the instantaneous water level and the local beach slope to attain this transformation79. Although the proposed method was originally designed and works best in microtidal settings, the selection of new appropriate shoreline proxies (e.g. wet-dry interphase or dune vegetation limit) could extend its utility to dissipative coasts with higher tidal ranges30,41. The employment of new proxies to represent coastline change could also enable the application in other coastal environments such as cliffs or urban coastal fronts79.

On coasts such as the Mediterranean (where recreational use of the beaches is high and there are numerous engineering actions) there is a high revisit frequency of satellite images. In high cloud coverage regions, the approach can be hampered by a lower number of useful images. Similarly, clouds can limit the availability of satellite imagery after storms, impeding a detailed characterisation of the beach morphology during their aftermath. These information gaps could be even more critical in tidal and/or energetic environments where the availability of fewer records would exacerbate the influence of water level changes, and severely hinder the detection and quantification of actual morphological changes.

Traditional monitoring is usually performed on the basis of topo-bathymetric profiles (from the foot of the dune to the depth of closure) and from these measurements, changes in volume are evaluated. Monitoring based on SDWLs can only detect changes in beach width. The variations can only be considered as an indication of the real changes. Nevertheless, the shoreline position changes may directly relate to volumetric changes on a particular beach61. In any case, depending on the characteristics of the study site and the monitoring purposes, the approach based on characterising coastline changes constitutes a robust technique for morphological characterisation when combined with 3D data. Although satellite-derived shorelines may robustly quantify the trends and erosion/accretion patterns, they provide bidimensional information with intrinsic limitations regarding the decimetre spatial accuracy. In general, they do not allow us to identify the most subtle coastline changes or the dynamism of the sediment on dunes and submerged parts of the beach. While techniques able to derive three-dimensional surfaces are being developed and the creation of seamless topo/bathy surveys is expected in the future80, the quantitative assessment of beach morphology using 3D methods is still scarce79, and in situ techniques as topographic surveys with the support of global navigation satellite systems (GNSSs) or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) can still constitute a highly accurate source of 3D data in the short term23 to complement the information provided by the SDWLs. This is the case in Valencia, where the dune restoration actions seem to play a key role as sediment input (see Fig. 11), but for which detailed volumetric quantification of the dune field and its evolution52 is required to quantify and understand the sediment dynamism over the coastal sector.

Conclusions

The methodology presented in this work has a high potential for defining the state of beaches and quantifying changes along large stretches of coastline in a response to coastal engineering projects. The results presented here demonstrate the ability for systematic monitoring of the shoreline position using Landsat and S2 satellite image series. They allow the characterisation of the response of beaches both in high detail at local scale as well as over long and sedimentarily interconnected coastal segments and over periods of time long enough to demonstrate the persistence or otherwise of long-term trends.

The combination of the large shoreline dataset and methods for organising this information and deriving useful indicators such as the beach width may constitute a comprehensive approach to monitor civil engineering interventions, assess their effectiveness, and support the adoption of measures to enable the physical maintenance of beaches.

A detailed sequence of spatial and temporal changes can be detected and portrayed such that the success and longevity of various interventions can be assessed. This offers a step-change improvement on traditional approaches and is in addition, not costly. This provides key data to understand the coastal engineering actions and to support coastal decision-making.

Data availability

All satellite imagery employed in this work is publicly available from Copernicus and USGS servers.

References

Turner, R. K. Integrating natural and socio-economic science in coastal management. J. Mar. Syst. 25, 447–460 (2000).

Gormsen, E. The impact of tourism on coastal areas. GeoJournal 42, 39–54 (1997).

Houston, J. R. The value of florida beaches. Shore Beach 81, 4–11 (2013).

Lazarow, N., Raybould, M. & Anning, D. Beach, sun and surf tourism. In Handbook of Tourism Economics Analysis, New Applications and Case Studies (ed. Tisdell, C.) 361–389 (World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2013).

Mestanza-Ramón, C. et al. An attempt to characterize the “3S” (sea, sun, and sand) parameters: Application to the galapagos Islands and continental ecuadorian beaches. Sustainability 12, 3468 (2020).

Alexandrakis, G., Manasakis, C. & Kampanis, N. A. Valuating the effects of beach erosion to tourism revenue. Manag. Perspect. Ocean Coast Manag. 111, 1–11 (2015).

Phillips, M. R. & Jones, A. L. Erosion and tourism infrastructure in the coastal zone: Problems, consequences and management. Tour. Manag. 27, 517–524 (2006).

Bird, E. C. Coastal erosion and rising sea-level. In Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Subsidence: Causes, Consequences, and Strategies (ed. Bird, E. C.) (Springer, 1996).

Nicholls, R. J. & Cazenave, A. Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal zones. Science 328, 1517–1520 (2010).

Slott, J. M., Murray, A. B., Ashton, A. D. & Crowley, T. J. Coastline responses to changing storm patterns. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L18404 (2006).

Alves, B., Rigall-I-Torrent, R., Ballester, R., Benavente, J. & Ferreira, Ó. Coastal erosion perception and willingness to pay for beach management (Cadiz, Spain). J. Coast. Conserv. 19, 269–280 (2015).

Koutrakis, E. et al. ICZM and coastal defence perception by beach users: Lessons from the mediterranean coastal area. Ocean Coast. Manag. 54, 821–830 (2011).

Hanson, H. et al. Beach nourishment projects, practices, and objectives—A European overview. Coast. Eng. 47, 81–111 (2002).

Staudt, F. et al. The sustainability of beach nourishments: a review of nourishment and environmental monitoring practice. J. Coast. Conserv. 25, 1–24 (2021).

de Schipper, M. A., Ludka, B. C., Raubenheimer, B., Luijendijk, A. P. & Schlacher, T. A. Beach nourishment has complex implications for the future of sandy shores. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2 (1), 70–84 (2021).

Palazón, A., Aragonés, L. & López, I. Evaluation of coastal management: Study case in the province of Alicante Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 572, 1184–1194 (2016).

Tonnon, P.K. et al. Uitvoeringsprogramma monitoring en evaluatie Pilot Zandmotor. Technical Report at https://www.vliz.be/imisdocs/publications/256419.pdf (2011).

Strauss, D., Murray, T., Harry, M. & Todd, D. Coastal data collection and profile surveys on the gold coast: 50 years on. In Australasian Coasts & Ports 2017: Working with Nature: Working with Nature (eds Strauss, D. et al.) (Engineers Australia PIANC Australia and Institute of Professional Engineers, 2017).

Ruggiero, P., Kaminsky, G. M., Gelfenbaum, G. & Voigt, B. Seasonal to interannual morphodynamics along a high-energy dissipative littoral cell. J. Coast. Res. 21, 553–578 (2005).

Lerma, A. N. et al. Decadal beach-dune profile monitoring along a 230-km high-energy sandy coast: Aquitaine, Southwest France. Appl. Geogr. 139, 102645 (2022).

Bradbury, A., Mason, T. & Barter, P. W. J. Large-scale multiagency strategic beach monitoring of the South-East Coast of England–provision of data and analytical tools. Proc. 2005 National Conference on Beach Preservation Technology (2005).

Mason, D. C., Gurney, C. & Kennett, M. Beach topography mapping—A comparison of techniques. J. Coast. Conserv. 6, 113–124 (2000).

Turner, I. L., Harley, M. D., Almar, R. & Bergsma, E. W. Satellite optical imagery in coastal engineering. Coast. Eng. 167, 103919 (2021).

Vitousek, S. et al. The future of coastal monitoring through satellite remote sensing. Camb. Prisms Coast. Futures 1, e10 (2023).

Belward, A. S. & Skøien, J. O. Who launched what, when and why; trends in global land-cover observation capacity from civilian earth observation satellites. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 103, 115–128 (2015).

Mahrad, B. E. et al. Contribution of remote sensing technologies to a holistic coastal and marine environmental management framework: a review. Remote Sens. 12, 2313 (2020).

Bernatchez, P. & Fraser, C. Evolution of coastal defence structures and consequences for beach width trends, Québec, Canada. J. Coast. Res. 28, 1550–1566 (2012).

Teodoro, A. C., Pais-Barbosa, J., Veloso-Gomes, F. & Taveira-Pinto, F. Evaluation of beach hydromorphological behaviour and classification using image classification techniques. J. Coast. Res. 56, 1607–1611 (2009).

Zhou, X., Wang, J., Zheng, F., Wang, H. & Yang, H. An overview of coastline extraction from remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 15, 4865 (2023).

Vos, K. et al. Benchmarking satellite-derived shoreline mapping algorithms. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 345 (2023).

Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Almonacid-Caballer, J., Ruiz, L. A. & Palomar-Vázquez, J. Automatic extraction of shorelines from landsat TM and ETM+ multi-temporal images with subpixel precision. Remote Sens. Environ. 123, 1–11 (2012).

Palomar-Vázquez, J., Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Almonacid-Caballer, J. & Cabezas-Rabadán, C. Shoreline analysis and extraction tool (SAET): A new tool for the automatic extraction of satellite-derived shorelines with subpixel accuracy. Remote Sens. 15, 3198 (2023).

Cabezas-Rabadán, C., Pardo-Pascual, J. E. & Palomar-Vázquez, J. Characterizing the relationship between the sediment grain size and the shoreline variability defined from Sentinel-2 derived shorelines. Remote Sens. 13, 2829 (2021).

Palomar-Vázquez, J., Almonacid-Caballer, J., Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Cabezas-Rabadán, C. & Fernández-Sarría, A. Sistema para la extracción masiva de líneas de costa a partir de imágenes de satélite de resolución media para la monitorización costera: SHOREX. in XVIII Congreso de Tecnologías de la Información Geográfica 36–46 (2018).

Thieler, E. R., Himmelstoss, E. A., Zichichi, J. L. & Ergul, A. The Digital Shoreline Analysis System (DSAS) Version 4.0 - An ArcGIS extension for calculating shoreline change. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1278 at https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20081278 (2009).

Facun, L. P. et al. QGIS shoreline change analysis tool (QSCAT): A fast, open-source shoreline change analysis plugin for QGIS. Environ. Model. Softw. 184, 106263 (2025).

Cabezas-Rabadán, C., Pardo-Pascual, J. E. & Palomar-Vázquez, J. Characterizing beach changes using high-frequency sentinel-2 derived shorelines on the valencian coast (Spanish Mediterranean). Sci. Total Environ. 691, 216–231 (2019).

Sánchez-García, E. et al. An efficient protocol for accurate and massive shoreline definition from mid-resolution satellite imagery. Coast. Eng. 2020, 103732 (2020).

Sánchez-García, E. et al. Beach monitoring project on central Chile. 5ª Conferência MEC2019 (2019).

Cabezas-Rabadán, C., Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Palomar-Vázquez, J., Ferreira, Ó. & Costas, S. Satellite derived shorelines at an exposed meso-tidal beach. J. Coast. Res. 95, 1027 (2020).

Pardo-Pascual, J. E. et al. Assessment of satellite-derived shorelines automatically extracted from sentinel-2 imagery using SAET. Coast. Eng. 188, 104426 (2024).

Cabezas-Rabadán, C. et al. Assessing satellite-derived shoreline detection on a mesotidal dissipative beach. Remote Sens. 16, 617 (2024).

Konstantinou, A. et al. Satellite-based shoreline detection along high-energy macrotidal coasts and influence of beach state. Mar. Geol. 462, 107082 (2023).

Pardo-Pascual, J. E. & Sanjaume, E. Beaches in valencian coast. In The Spanish Coastal Systems: Dynamic Processes, Sediments and Management (ed. Morales, J. A.) (Springer, 2019).

Sanjaume, E. Las costas valencianas: sedimentología y morfología. PhD thesis, Universidad de Valencia (1985).

Toledo, I., Pagán, J. I., López, I. & Aragonés, L. Causes of the different behaviour against erosion: Study case of the benidorm beaches (1956–2021). Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 41, 648–661 (2023).

Nolasco-Cirugeda, A., Martí, P. & Ponce, G. Keeping mass tourism destinations sustainable via urban design: The case of benidorm. Sustain, Dev. 28, 1289–1303 (2020).

Rico-Amorós, A. M., Olcina-Cantos, J. & Saurí, D. Tourist land use patterns and water demand: Evidence from the Western Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 26, 493–501 (2009).

INE, National Statistics Institute. Spanish Statistical Office. https://www.ine.es/ (2023).

Ministerio de Obras Públicas y Transportes (MOPT). Proyecto de liquidación de obras de emergencia de la playa de Poniente de Benidorm (Alicante). Technical Report at https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/costas/publicaciones.html (1991).

Aragonés, L., García-Barba, J., García-Bleda, E. & López, I. Beach nourishment impact on posidonia oceanica: Case study of poniente beach (Benidorm, Spain). Ocean Eng. 107, 1–12 (2015).

Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Cabezas-Rabadán, C. & Palomar-Vázquez, J. Anàlisi dels cànvis morfològics del cordo dunar i les platges de la Devesa del Saler a consequència del temporal Gloria. In A Vicenç M Rosselló, geògraf, als seus 90 anys (eds Pardo-Pascual, J. E. et al.) (Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2021).

Sanjaume, E. & Pardo-Pascual, J. E. Littoral dunes on valencia coast. In The Spanish Coastal Systems: Dynamic Processes, Sediments and Management (ed. Morales, J. A.) (Springer, 2019).

Cobo, R. Los sedimentos de los embalses españoles. Ing. Agua 15, 231–241 (2008).

Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Palomar-Vázquez, J. & Cabezas-Rabadán, C. Estudio de los cambios de posición de la línea de costa en las playas del segmento valència-cullera (1984–2020) a partir de imágenes de satélite de resolución media de libre acceso. Cuad. Geogr. Univ. València 108, 79–104 (2022).

Amrouni, O., Heggy, E. & Hzami, A. Shoreline retreat and beach nourishment are projected to increase in Southern California. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 274 (2024).

Browder, A. E. & Dean, R. G. Monitoring and comparison to predictive models of the perdido key beach nourishment project, Florida, USA. Coast. Eng. 39, 173–191 (2000).

Seymour, R., Guza, R. T., O’Reilly, W. & Elgar, S. Rapid erosion of a small Southern California beach fill. Coast. Eng. 52, 151–168 (2005).

Bakker, M. A., van Heteren, S., Vonhögen, L. M., van der Spek, A. J. & Van der Valk, B. Recent coastal dune development: effects of sand nourishments. J. Coast. Res. 28, 587–601 (2012).

Griggs, G. Beach nourishment: A critical look. J. Coast. Res https://doi.org/10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-24A-00004.1 (2024).

Houston, J. R. Measured fate of beach nourishment sand. J. Coast. Res. 39, 407–417 (2023).

Li, J. & Chen, B. Global revisit interval analysis of landsat-8-9 and sentinel-2A-2B data for terrestrial monitoring. Sensors 20, 6631 (2020).

Cabezas-Rabadán, C., Pardo-Pascual, J. E., Palomar-Vázquez, J. & Roch-Talens, A. Satellite observations of storm erosion and recovery of the ebro delta coastline, NE Spain. Coast. Eng. 188, 104451 (2024).

Ballesteros, C., Jiménez, J. A., Valdemoro, H. I. & Bosom, E. Erosion consequences on beach functions along the Maresme coast (NW Mediterranean, Spain). Nat. Hazards 90, 173–195 (2018).

Houston, J. R. The economic value of beach nourishment in South Carolina. Shore Beach 89, 3–12 (2021).

Houston, J. R. The economic value of Florida’s beaches. Shore Beach 86, 1–11 (2018).

Wulder, M. A. et al. Current status of landsat program, science, and applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 225, 127–147 (2019).

Saleem, A. & Awange, J. L. Coastline shift analysis in data deficient regions: exploiting the high spatio-temporal resolution sentinel-2 products. Catena 179, 6–19 (2019).

Vos, K., Harley, M. D., Turner, I. L. & Splinter, K. D. Pacific shoreline erosion and accretion patterns controlled by El Niño/Southern Oscillation. Nat. Geosci. 16, 140–146 (2023).

Castelle, B. et al. Satellite-derived sandy shoreline trends and interannual variability along the Atlantic coast of Europe. Sci. Rep. 14, 13002 (2024).

Briceño de Urbaneja, I. et al. Characterization of multi-decadal beach changes in Cartagena Bay (Valparaíso, Chile) from satellite imagery. Remote Sens. 16, 2360 (2024).

Baptista, P., Bastos, L., Bernardes, C., Cunha, T. & Dias, J. Monitoring sandy shores morphologies by DGPS—A practical tool to generate digital elevation models. J. Coast. Res. 24, 1516–1528 (2008).

Do, K., Kobayashi, N. & Suh, K.-D. Erosion of nourished bethany beach in Delaware, USA. Coastal Eng. J. 56, 1450004 (2014).

Roberts, T. M. & Wang, P. Four-year performance and associated controlling factors of several beach nourishment projects along three adjacent barrier islands, west-central Florida, USA. Coast. Eng. 70, 21–39 (2012).

Pajak, M. J. & Leatherman, S. The high water line as shoreline indicator. J. Coast. Res. 329, 329–337 (2002).

Gares, P. A., Wang, Y. & White, S. A. Using LIDAR to monitor a beach nourishment project at Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina. USA. J. Coast. Res. 22, 1206–1219 (2006).

Ojeda, E. & Guillén, J. Monitoring beach nourishment based on detailed observation with video measurements. J. Coast. Res. 48, 100–106 (2006).

Castelle, B. et al. Satellite-derived shoreline detection at a high-energy meso-macrotidal beach. Geomorphology 383, 107707 (2021).

Gomez da Silva, P. G., Jara, M. S., Medina, R., Beck, A. L. & Taji, M. A. On the use of satellite information to detect coastal change: Demonstration case on the coast of Spain. Coast. Eng. 191, 104517 (2024).

Bergsma, E. W. et al. Coastal morphology from space: A showcase of monitoring the topography-bathymetry continuum. Remote Sens. Environ. 261, 112469 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the SIMONPLA subproject integrated within the ThinkinAzul programme by the Ministry of Science and Innovation with funds from the European Union NextGeneration EU (PRTR-c17.I1) and Generalitat Valenciana, contract CIAPOS/2023/394 funded by the Generalitat Valenciana and the European Social Fund Plus, and the grant Primeros Proyectos de Investigación (PAID-06-22) by Vicerrectorado de Investigación, Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC-R: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, review & editing; JEP-P: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, review & editing; JP-V: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—review & editing; AC: Conceptualization, Writing—original draft, review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cabezas-Rabadán, C., Pardo-Pascual, J.E., Palomar-Vázquez, J. et al. A remote monitoring approach for coastal engineering projects. Sci Rep 15, 2955 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86485-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86485-y