Abstract

The sustainable treatment and reuse of waste slurry in slurry shield construction have gained significant attention. This paper explores the application of magnetic flocculation technology for treating slurry. The CFD-DEM coupling method simulates the migration of magnetic flocs during centrifugation. Two evaluation indexes of magnetic content of floc residue (MCFR) and magnetic seed recovery rate (MSRR) are introduced. The study examines how magnetic seed concentration, feed rate, and differential speed affect floc movement, magnetic seed separation, and recovery, proposing directions for optimizing separation technology. Due to computational limitations, the simulation focuses exclusively on the process from floc entry into the decanter centrifuge to its exit at the drum’s end. Results indicate that changes in centrifugal parameters significantly affect floc movement, with feed rate showing the strongest positive correlation with MSRR, followed by differential speed. As magnetic seed concentration increases, both MCFR and MSRR rise. However, when concentration becomes too high, MSRR begins to decrease. Feed rate strongly influences magnetic floc behavior, with MCFR and MSRR showing complementary trends. Through the transformation of the separation equipment, the MSRR can be increased to 93.4%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, China has achieved significant advancements in shield technology, with the widespread use of both earth pressure balance and slurry balance shields in construction1,2. The slurry shield, with its ability to manage slurry pressure in the excavation chamber, is the preferred method for large river-crossing tunnels. Notable projects like the completed Jinan Yellow River Tunnel, Nanjing Yangtze River Tunnel, and other river-crossing tunnels across Chinese cities have adopted or are planning to adopt slurry shield construction3,4. However, slurry shield tunneling has led to several environmental challenges. During excavation, soil mixed with fresh slurry is pumped from the chamber to the surface slurry treatment station via slurry pipes. While a small portion of the slurry is reused in the circulation system, a significant amount of waste slurry must be processed and reused. In high-viscosity strata, the slurry shield produces considerably more waste slurry compared to sand layers. For instance, each ring of the Yellow River Tunnel produces over 1000 m3 of waste slurry5.

Currently, the disposal methods for waste slurry are mainly chemical flocculation and mechanical dehydration (including pressure filtration, centrifugation, etc.)6. Wang et al.7 examined the rapid dehydration of construction waste mud through chemical flocculation, noting that organic flocculants perform better than inorganic and composite alternatives. Jiang et al.8 added conditioner and curing agent to make the waste slurry flocculate and settle quickly, which greatly improved the disposal efficiency. Xu et al.9 analyzed how flocculant type and dosage impact the sedimentation of kaolin slurry, showing that polymer flocculants’ adsorption bridging effect primarily determines floc size. Traditional flocculation methods can reduce waste slurry to some extent. However, most research focuses on the separation effects based on flocculant type and ratio, while chemical flocculation suffers from slow sedimentation and high time costs10. Magnetic flocculation, a new technology developed from traditional flocculation, addresses the issue of slow sedimentation11. Zhang et al.12 studied magnetic flocculation in wastewater sludge, finding that magnetic seeds significantly reduce settling time, with seed recovery enhancing cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, Sha et al.13 combined traditional coagulants (PAC, PAM) with magnetic powder to evaluate wastewater treatment performance under varying conditions. Their findings showed that magnetic flocs exhibited far better sedimentation performance than regular flocs. Tang et al.14 carried out research on the application of magnetic flocculation process in oily wastewater, and pointed out that magnetic seed can enhance electrical neutralization and hydrogen bond adsorption. Liu et al.15 experimentally verified the feasibility of treating kaolin suspension using the magnetic flocculant Fe3O4/SiO2, identifying Fe3O4/SiO2 and Ca2+ as key factors influencing removal rates. Existing studies confirm magnetic flocculation’s feasibility in treating waste slurry, resolving the slow sedimentation issue of traditional flocculation, but also raising a new challenge: the recovery efficiency of magnetic seeds in magnetic flocs16,17. Magnetic separation technology can be categorized into direct magnetic separation and inoculated magnetic separation, depending on the process18. Typically, waste slurry of shield tunnel lacks ferromagnetic materials, so equipment for separating magnetic particles, such as cyclone separators, ultrasonic devices, and backwash water systems, are needed to capture magnetic species. Research primarily relies on experimental comparisons to assess magnetic seed recovery across different device designs. Due to limitations in devices and monitoring methods, the magnetic seed recovery process is not well-analyzed, leaving conclusions based only on end results. With the advancement of numerical simulation methods, fluid-particle interactions can now be studied at the particle scale. The Discrete Element Method (DEM) is one of the most commonly used numerical methods for solid-phase simulations. In DEM, individual particles are explicitly modeled using Newton–Euler equations, allowing for a direct analysis of particle interactions and providing detailed insights into particle motion characteristics. When particle–fluid interactions significantly influence particle behavior, the fluid phase must also be incorporated into the simulation process. For the liquid phase, fluid–solid coupling simulations typically use two numerical approaches: particle-based methods and grid-based methods. In particle-based methods, the fluid is primarily modeled using Smoothed-Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH). In grid-based methods, the fluid is described by the locally averaged Navier–Stokes equations, which can be solved using conventional Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methods based on finite element or finite volume techniques. SPH is a mesh-free Lagrangian method that has been successfully applied to simulate various complex fluid flows 19. Compared to traditional mesh-based methods, SPH is more capable of accurately handling large interface deformations and free surfaces. However, the treatment of boundary conditions in SPH is complex20, and the computational cost of SPH is generally high21. Depending on the modeling resolution of the fluid and the relative size of the particles, the CFD-DEM method can be categorized into unresolved and resolved methods. The unresolved method uses volume-averaged Navier–Stokes equations, where the computational mesh is coarser than the particle size, making it suitable for large-scale simulations.

This paper focuses on the treatment of waste slurry generated during slurry balance shield construction using magnetic flocculation technology. It employs CFD-DEM coupling to simulate the migration of magnetic flocs during centrifugation and to model the recovery process of magnetic seeds from the flocculation state. The study enables comprehensive monitoring and analysis of particle movement in the flow field. It investigates how process parameters affect the movement of magnetic flocs and magnetic seed separation, exploring the potential and optimization of combining magnetic seed separation with centrifugal dehydration. This provides a reference for the efficient treatment and resource utilization of waste slurry in slurry shield.

Magnetic flocculation-centrifugal dehydration process

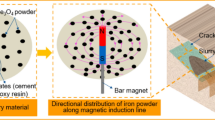

Mechanism of magnetic flocculation

Magnetic flocculation technology involves adding magnetic seeds during the flocculation process to enhance coagulation and flocculation. Since the density of magnetic seeds is significantly higher than water, flocs containing magnetic seeds have an increased specific gravity, allowing them to settle quickly in the sedimentation tank. Researchers suggest that floc formation is driven by the combined action of coagulants and flocculants22. The process of forming magnetic flocs can be described as follows (see Fig. 1):

-

a.

After adding polyaluminium chloride (the coagulant), the cations produced by its hydrolysis accumulate around the negatively charged suspended particles and magnetic seed particles due to the compression of the electric double layer, thereby “destabilizing” the particles. This destabilization reduces the repulsive forces between the particles, facilitating their aggregation through collision, surface adsorption, van der Waals attraction, and other mechanisms, which promotes agglomeration and aids in separation from water.

-

b.

After adding polyacrylamide (the flocculant), which is typically a high-molecular-weight polymer, it adsorbs multiple particles onto its structure. The bridging effect of the polymer aggregates the particles into larger clusters. Its long-chain structure forms a “bridge” between particles, further enhancing particle aggregation and the formation of larger flocs, thus accelerating the sedimentation process.

In summary, the coagulant and flocculant interact through distinct mechanisms during the treatment process. The coagulant destabilizes the particles, while the flocculant promotes further aggregation through the bridging effect. Together, they enhance the overall treatment efficiency.

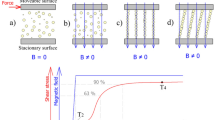

Mechanism of magnetic seed separation based on centrifugal force

Reducing the cost of magnetic seeds requires efficient recovery and reuse, which can be achieved using a decanter centrifuge. This device generates strong centrifugal forces and is commonly used for magnetic seed recovery23,24. The separation process relies on the difference in specific gravity and centrifugal force between the various components of the magnetic flocs. The decanter centrifuge consists of two main parts: the cylindrical section and the conical section (see Fig. 2). When the water carrying the magnetic flocs enters the drum via the feed pipe, it is immediately subjected to centrifugal force and thrown into the drum cavity. As the fluid spirals from top to bottom along the outer wall, the rotating flow generates significant centrifugal force. The magnetic seed particles, which are denser, are thrown against the inner wall of the drum, forming a solid ring layer. In contrast, the floc particles, being lighter, experience less centrifugal force and remain within the inner side of the solid-ring layer. Due to the differential rotational speeds of the drum and the screw, a relative motion is created between the two (i.e., differential rotational speed). This causes the magnetic seed particles within the solid-ring layer to be pushed toward the cylindrical wall, where they are carried toward the cylindrical section of the drum by the rotating motion.

Simulation method of magnetic flocs

Governing equations

The discrete element method (DEM)25 is commonly used to analyze the behavior of granular materials like rock and sand. Unlike the traditional continuous method, DEM simulates granular materials using discrete particle models. Particles exhibit two types of motion: translation and rotation. The motion of individual particles is governed by Newton’s laws of motion and contact criteria:

Here, mpi and Ipi represent the mass and moment of inertia of particle I; the translational and angular velocities are denoted as \(\vec{u}_{pi}\) and \(\vec{\omega }_{pi}\), respectively. nc is the number of contacts, while \(\vec{F}_{pij}^{c}\), \(\vec{F}_{pi}^{g}\), \(\vec{F}_{pi}^{f}\) represent contact force, gravity and force between fluid particles, respectively; \(\vec{M}_{pij}\) is the moment of particle i at contact j.

This paper considers the cohesive force between floc particles and magnetic seed particles, influenced by van der Waals forces, using the Johnson-Kendall-Roberts (JKR) model 26. The JKR model is well-suited for simulating the cohesion of granular materials with low cohesive energy and Young’s modulus, such as mud suspensions. The JKR normal force is determined by the overlap between particles (δ) and the surface energy (γ):

Here, \(E^{ * }\) is the equivalent Young’s modulus and \(R^{ * }\) is the equivalent radius.

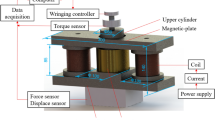

CFD-DEM coupling scheme

The CFD-DEM simulation was conducted using the commercial software Ansys Fluent 2022 and EDEM 2022. The coupling algorithm is central to the CFD-DEM method. Based on the Euler–Lagrange framework, it enables two-way interaction between fluid (CFD) and particle (DEM) solvers and can track individual particles27. Initially, Fluent calculates a custom environment, and EDEM retrieves particle position data to compute mesh porosity and fluid-particle interaction forces. EDEM calculates the velocity and position of discrete particles, which are then input into Fluent to analyze the particle flow field and update the system. Once the iteration converges, the fluid grid state and the interaction force are updated (see Fig. 3).

Simulation setup

A simplified model of the decanter centrifuge, as shown in Fig. 2, was created without affecting the simulation results. As illustrated in Fig. 4a, the rotary drum’s straight section has an inner diameter of 380 mm and a length of 600 mm, while the cone section has a length of 400 mm. Due to computational constraints, only five spirals of the decanter centrifuge, including the cone section, were simulated, with a pitch of 200 mm. The simulation involves discrete magnetic seed particles with an average size of 0.15 mm and floc particles with an average size of 0.5 mm. Previous DEM tests indicate that enlarging particle size slightly does not significantly affect physical or mechanical behavior28. For computational efficiency, particle sizes were uniformly increased by a factor of 10. Floc particles were modeled as three-spherical to account for their aggregation behavior. Due to test container limitations, the floc morphology differs from that in the pumping process, preventing further soil testing for accumulation angle calibration. In this simulation, particle, wall, and contact parameters were estimated based on their macroscopic phase characteristics, as referenced in the papers29,30 (see Table 1).

The flow of magnetic flocs in the decanter centrifuge was simplified as steady, incompressible, and without considering temperature changes. A velocity inlet boundary condition is adopted, with a velocity range of 0.5–1.0 m s−1 and a hydraulic diameter D of 70.0 mm. To accommodate grid constraints near the wall, the standard wall function method was applied, ensuring the velocity non-slip condition was met. Magnetic flocs are generated to the left of the feed inlet using the dynamic particle factory in EDEM, and are coupled with Fluent to simulate their entry into the decanter centrifuge under the influence of the flow field. This setup allows for the simulation of particle movement and the screening effect under centrifugal forces. The magnetic flocs consist of both floc particles and magnetic seed particles. By controlling the total particle inflow mass concentration, the proportion of magnetic seed particles is adjusted based on varying magnetic seed concentration conditions. In this simulation, the unsolved CFD-DEM coupling scheme is used, and the CFD grid will not deform with the movement of particles during the calculation. This simplification is based on the consideration of computational efficiency. However, due to the limitation of the algorithm in calculating porosity and drag force, this method requires that the size of the fluid grid must be 2–4 times larger than that of the particles31,32. But too coarse grid will affect the modeling accuracy. Therefore, the appropriate grid is very important for the efficiency and accuracy of the simulation. In this paper, there are two particle sizes of 1.5 mm and 5 mm, so the mesh size of the fluid is slight greater than 2Dmax. The fluid domain was divided into 104,271 hexahedral meshes, as shown in Fig. 4b. Based on the Rayleigh criterion, the DEM time step was set to 4.0 × 10−5 s, and the CFD time step was set 10 times longer, at 4.0 × 10−4 s33. The total simulation time was set to 2 s to ensure the integrity of the process.

Results and analysis

Evaluation indicators

To evaluate the effectiveness of magnetic seed separation in the decanter centrifuge, two key evaluation indexes were introduced: the Magnetic Content of Floc Residue (MCFR) and the Magnetic Seed Recovery Rate (MSRR).

Magnetic content of floc residue (MCFR)

MCFR refers to the ratio of the magnetic seed mass to the total mass of the particle phase in the cone section of the decanter centrifuge. This is expressed by Eq. (3):

where, m1 is the mass of the magnetic seed in the cone section (kg) ; m is the total mass of the particle phase in the cone section (kg).

Magnetic seed recovery rate (MSRR)

MSRR is defined as the ratio of the mass of magnetic seeds recovered in the cone section to the initial mass of magnetic seeds, as shown in Eq. (4):

where, m1 is the mass of magnetic seed particles in the straight cylinder (kg) ; m0 is the initial mass of magnetic seeds (kg).

Model validation

The team conducted a magnetic flocculation-centrifugal dewatering test on shield tunnel waste slurry, and the process is shown in Fig. 5. Magnetic seeds, poly aluminum ferric chloride (PAFC), and anionic polyacrylamide (APAM) were added to the waste slurry. A high-speed stirrer was then used to ensure thorough mixing of the components with the slurry, resulting in the formation of large particle flocs. Once the mixer reached the preset duration, the beaker was placed flat at the center of the electromagnet pole surface, and a magnetic field was applied to facilitate the further precipitation of the flocs. The magnetic flocs were then transferred into a centrifuge flask, and centrifugation was initiated to analyze the effect of centrifugal parameters on the distribution of magnetic species within the magnetic flocs.

Based on the adaptive correction algorithm of the two-dimensional gamma function and the binarization method, the image of the bottom of the centrifugal bottle was processed to highlight the effect of magnetic seed separation. The impact of magnetic seed separation in magnetic flocs at different centrifugal times is shown in the Fig. 5. Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of particle phases in the drum at various times under the coupled simulation method, with brown and black representing flocs and magnetic particles, respectively. When the magnetic floc is fed into the drum from the feed pipe, it is immediately thrown into the drum cavity under the influence of the centrifugal force field. Due to differences in particle specific gravity, some magnetic particles are separated from the particle group and deposited onto the inner wall of the drum. As the centrifugal process progresses, a small number of magnetic seed particles near the inner wall of the drum are further pressed against the wall by surrounding floc particles, consistent with the experimental observations. Due to the differing rotational speeds of the drum and the screw, relative motion between the two causes the floc sediment deposited on the inner wall to gradually move toward the cone end of the drum. The working principle of the actual decanter centrifuge confirms the validity of the model established in this study.

Effect of magnetic seed concentration on the movement of magnetic flocs

Simulations were conducted to analyze the effect of different magnetic seed concentrations on separation efficiency, with the following conditions: a feed rate of 0.6 m/s, a rotary drum speed of 1000 rpm, and a differential speed of 20 rpm between the screw and the rotary drum. The simulation results are presented in Fig. 7.

The concentration of magnetic seeds has minimal impact on the movement of particles. Instead, the key differences across conditions lie in how magnetic seeds are distributed, particularly in terms of the Magnetic Content of Floc Residue (MCFR) and the quantity of separated magnetic seeds. Most stripped magnetic seeds accumulate near the right discharge port. Since there is a gap between the screw and the rotary drum, magnetic seeds and the drum remain relatively stationary after separation. However, some seeds are forced into the cone section due to particle interactions, while unseparated seeds are pushed into the cone section along with floc particles. To understand the observed phenomenon, we analyzed the position coordinates of magnetic seeds in the rotary drum at 2 s, as illustrated in Fig. 8a. Due to the dynamic nature of centrifugation, particle positions are updated frequently, causing magnetic seeds near the drum’s inner wall to frequently come into contact with it. Figure 8b shows that magnetic seed particles are predominantly concentrated at the junction between the cone and straight sections. This accumulation occurs because the cone wall exerts a reaction force on the particles, which impedes their movement into the left cone section. As a result, the density of magnetic seeds in this area is notably higher compared to previous section.

To quantify the effect of different magnetic seed concentrations on separation efficiency, we used EDEM software to count the number of particles in the cone section and calculated the MCFR and the MSRR. The results are summarized in Fig. 9.

As the magnetic seed concentration increases, the MCFR rises almost linearly. This suggests that without additional separation methods, the amount of magnetic seeds added during flocculation will directly influence the magnetic content of the dewatered product. On the other hand, the MSRR shows an initial increase, followed by a decrease and stabilization. The peak recovery rate of 36.3% occurs when the magnetic seed concentration is 3.7‰. With the increase of magnetic seed concentration, the probability of magnetic seed particles being captured by the rotary drum increases, and the number of separated magnetic seeds increases accordingly. When the magnetic seed concentration exceeds 3.7‰, more seeds are pushed into the cone section with the floc, and the MSRR stabilizes around 33.5%. These findings indicate that, to minimize costs, the magnetic seed concentration should be kept low unless additional separation measures are implemented.

Effect of feed rate on the movement of magnetic flocs

The effects of different feed rates on the separation effect were analyzed under the conditions of magnetic seed concentration of 2.5‰, rotary drum speed of 1000 rpm, and differential speed between screw and rotary drum of 20 rpm. The simulation results are shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10 shows that variations in feed rate significantly affect particle phase movement. As the feed rate increases, more magnetic flocs enter the rotary drum per unit of time, expanding the width of the particle group in the spiral groove. Among them, the axial migration boundary of the particle group shows a clear tendency to move left until it reaches the wall of the cone end. Figure 9 further analyzes the position distribution of magnetic seeds and floc particles in the rotary drum. With higher feed rates, the circumferential distribution of floc particles widens, increasing the height of the particle group in the groove and leading to a higher concentration of magnetic particles (Fig. 11a). This raises the risk of rotary drum clogging. Figure 11c indicates that the magnetic seed enrichment point shifts from the cone section’s edge toward the outlet. As the feed rate rises, increased friction between particles and the drum wall, along with stronger inter-particle forces, heightens resistance to magnetic seed migration. This prolongs the particles’ residence time near the outlet. Due to differential speed, more floc particles accumulate in the cone section (Fig. 11d).

Figure 12 shows that as the feed rate increases, the trends of the two indices move in opposite directions. The magnetic content of floc residue (MCFR) decreases, while the magnetic seed recovery rate (MSRR) increases. Both stabilize at a feed rate of 0.8 m/s, with a recovery rate of 41.7%. Figure 11a illustrates that magnetic flocs are ejected through the discharge port, with most magnetic seed particles coming into contact with the drum wall. At low feed rates, friction between the particles and the drum wall is minimal, and inter-particle forces are weak, resulting in low migration resistance for magnetic seeds that touch the wall. As a result, only a small number of particles are pushed to the cone section by particle interaction, leading to a low MSRR. As feed rate increases, magnetic seed migration resistance also rises, reducing “forced movement” and thus increasing MSRR. When the feed rate exceeds 0.8 m/s, more magnetic seed particles are trapped within the flocs and carried to the cone section, preventing further increases in MSRR. Thus, selecting an appropriate feed rate, considering equipment size and process conditions, is crucial to avoid unnecessary costs from magnetic seed loss.

Effect of differential speed on the movement law of magnetic flocs

The effects of varying differential speeds on separation were analyzed at a magnetic seed concentration of 2.5‰, a feed rate of 0.6 m/s, and a rotary drum speed of 1000 rpm. The simulation results are displayed in Fig. 13.

Figure 14 illustrates that differential speed greatly influences particle movement, as discharge behavior is primarily driven by differential rotation speed. Higher differential speeds result in faster spiral transport of particles. Consequently, the axial boundary and width of the particle group in the spiral groove adjust accordingly. As the differential speed increases, the axial boundary of the particle group shifts leftward until it reaches the cone end wall, while the particle group’s width decreases. The distribution of magnetic seeds and floc particles at 2 s within the rotary drum was further analyzed. As differential speed increases, the accumulation of magnetic seed particles at the variable cone position weakens, as shown in Fig. 14a. At lower differential speeds, the discharge capacity cannot overcome the reaction force from the cone wall, blocking the migration of magnetic seed particles near the drum wall, leading to a higher distribution density compared to earlier sections. When the differential speed exceeds 25 rpm, these effects diminish, and magnetic seeds are carried to the cone section with the floc particles. Additionally, under the influence of differential speed, more floc particles migrate and accumulate in the cone section, as shown in Fig. 14b.

Figure 15 shows that as differential speed increases, the two indices exhibit opposite trends. The magnetic content of floc residue (MCFR) initially increases, then decreases, while the magnetic seed recovery rate (MSRR) first decreases and then rises, reaching up to 34.3% within the set range. At low differential speeds, particle contact time is prolonged, causing strong interactions that drive synchronous migration of the particle group. Increasing the differential speed at this point pushes more wall-contacting magnetic particles toward the cone section along with the floc particles. As differential speed increases, the axial migration of the particle group accelerates, reducing contact time with the wall-contacting magnetic seeds and weakening the ‘forced movement’ effect. Consequently, when the differential speed exceeds 25 rpm, MSRR begins to rise. Compared to feed rate, the effect of differential speed on MSRR is weaker, with MSRR remaining below 10.0% in the given range. This is primarily influenced by the axial distribution of particles, as changes in MSRR are driven by inter-particle interactions. Additionally, differential speed affects the spiral discharge rate. Under the same conditions, increasing differential speed enhances discharge capacity. However, the shorter residence time in the drum results in higher moisture content in the discharge. The analysis shows that differential speed has a limited impact on magnetic seed separation, with material dehydration remaining the dominant factor.

Discuss

According to the analysis, without additional separation methods, optimizing and adjusting process parameters only maintain the MSRR between 30 and 45%, with actual performance likely being lower. From an economic perspective, enhancing the MSRR is a priority. Based on the simulation results, we analyzed the magnetic seed capture ability by reinforcing the rotary drum. Adjusting the contact parameters between magnetic seed particles and the drum wall serves as an indirect measure of the drum’s enhanced capture ability. The simulation results are displayed in Figs. 16 and 17.

Once the capture ability was enhanced, the axial distribution of magnetic seeds and floc particles changed significantly under the same conditions. Magnetic seed particles became concentrated near the discharge port, while floc particles were pushed to the cone section by the spiral blades. As a result, the MSRR reached 93.4%. This demonstrates that increasing the drum’s ability to capture magnetic seeds significantly improves magnetic seed recovery. Therefore, it is possible to consider integrating the decanter centrifuge with the magnetic separator, as shown in Fig. 18. A detachable magnetic system embedded in the drum’s inner wall facilitates magnetic seed capture and recovery. The magnetic system can be made from materials like strontium ferrite and neodymium iron boron permanent magnets. When magnetic flocs enter the drum through the feed pipe, they are propelled into the drum cavity by centrifugal force. The difference in specific gravity between particles causes some magnetic seeds to separate from the group and be thrown onto the drum’s inner wall, where they are captured by the magnetic system. The smooth, grooved surface of the magnetic system is designed to capture magnetic particles that haven’t yet reached the wall. The proposed scheme focuses primarily on optimizing the recovery of magnetic seeds. However, further considerations are required during implementation to enhance the magnetic separator’s compatibility with the overall system.

Conclusions

In this paper, the CFD-DEM method was used to simulate the migration process of magnetic flocs during centrifugation, investigating the effects of various process parameters on their movement and magnetic seed separation. Due to computational limitations, the simulation focuses exclusively on the process from floc entry into the decanter centrifuge to its exit at the drum’s end. Additionally, the feasibility and optimization potential of combining magnetic seed separation with the centrifugal dehydration process were explored. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

The distribution of magnetic seeds is primarily influenced by their concentration. As the concentration increases, the magnetic content of floc residue (MCFR) shows a near-linear growth, while the magnetic seed recovery rate (MSRR) initially increases, then decreases, before stabilizing. Without auxiliary separation measures, a lower magnetic seed dosage is recommended to minimize unnecessary cost increases.

-

(2)

Feed rate significantly affects the movement of magnetic flocs. As the feed rate increases, the migration distance, distribution width, and accumulation height of solid slag in the spiral groove also increase. However, if the drum’s rotational speed is insufficient to facilitate the rapid separation of heavier substances, the MSRR will decrease accordingly.

-

(3)

Differential speed also plays a crucial role in the movement of magnetic flocs. With increasing differential speed, the migration distance of flocs per unit time increases noticeably. The trends for MCFR and MSRR are complementary, with the MSRR first decreasing and then increasing. Given that the MSRR remains below 10% within the tested range, the selection of differential speed should prioritize material dehydration.

-

(4)

Without additional separation measures, the MSRR achieved with existing centrifugation equipment remains between 30 and 45%, and actual results are likely to be lower. However, by embedding a detachable magnetic system into the inner wall of the drum, magnetic seed capture and recovery can be significantly enhanced. Simulation results show that this adjustment can increase the MSRR to 93.4%.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zizka, Z., Schoesser, B. & Thewes, M. Investigations on transient support pressure transfer at the tunnel face during slurry shield drive part 1: Case a-tool cutting depth exceeds shallow slurry penetration depth. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 118, 104168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2021.104168 (2021).

Yao, Y. et al. Experimental study on granule trajectory tracking for the EPB shield tunneling in Sandy Cobble stratum. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2024.105980 (2024).

Zhang, S., Cheng, X., Qi, L. & Zhou, X. Face stability analysis of large diameter shield tunnel in soft clay considering high water pressure seepage. Ocean Eng. 253, 111283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.111283 (2022).

Ding, Z., Zhang, M.-B., Zhang, X. & Wei, X.-J. Theoretical analysis on the deformation of existing tunnel caused by under-crossing of large-diameter slurry shield considering construction factors. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 133, 104913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104913 (2023).

Ding, Z., Liu, T., Zhang, Y., Su, X. & Zheng, J. The curing and strength properties of highly moist waste mud from slurry shield tunnel construction. Appl. Sci. 12, 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12083762 (2022).

Hyrycz, M., Ochowiak, M., Krupińska, A., Włodarczak, S. & Matuszak, M. A review of flocculants as an efficient method for increasing the efficiency of municipal sludge dewatering: Mechanisms, performances, influencing factors and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 820, 153328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153328 (2022).

Wang, D., Di, S., Wu, L., Tan, Y. & Tang, Y. Sedimentation behavior of organic, inorganic, and composite flocculant-treated waste slurry from construction works. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 33, 04021134. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003758 (2021).

Jiang, L., Zhen, L., Wang, J., Zhang, T. & Huang, X. Research on dewatering characteristics of waste slurry from pipe jacking construction. Materials 15, 2242. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15062242 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Flocculation and dewatering of the kaolin slurry treated by single- and dual-polymer flocculants. Chemosphere 328, 138445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138445 (2023).

Zhao, Y. Q. Settling behaviour of polymer flocculated water-treatment sludge I: Analyses of settling curves. Sep. Purif. Technol. 35, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1383-5866(03)00132-1 (2004).

Wang, S.-K. et al. Magnetic flocculant for high efficiency harvesting of microalgal cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1021/am404764n (2014).

Zhang, W. et al. Improvement of wastewater sludge dewatering performance using titanium salt coagulants (TSCs) in combination with magnetic nano-particles: Significance of titanium speciation. Water Res. 110, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.12.011 (2017).

Sha, S. et al. Enhanced precipitation performance for treating high-phosphorus wastewater using novel magnetic seeds from coal fly ash. J. Environ. Manage. 315, 115168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.115168 (2022).

Tang, J. et al. The investigation on Fe3O4 magnetic flocculation for high efficiency treatment of oily micro-polluted water. J. Environ. Manage. 244, 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.068 (2019).

Liu, C., Wang, X., Qin, L., Li, H. & Liang, W. Magnetic coagulation and flocculation of a kaolin suspension using Fe3O4 coated with SiO2. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2021.105980 (2021).

Sun, Y., Yu, Y., Zheng, X., Chen, A. & Zheng, H. Magnetic flocculation of Cu(II) wastewater by chitosan-based magnetic composite flocculants with recyclable properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 261, 117891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117891 (2021).

Fang, Y. et al. Effective dewatering and resourceful utilization of high-viscosity waste slurry through magnetic flocculation. Constr. Build. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136014 (2024).

Hu, Z., Wu, K., Wang, Z., Shah, K. J. & Sun, Y. Research progress of magnetic flocculation in water treatment. Magnetochemistry 10, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry10080056 (2024).

Vázquez-Quesada, A. & Ellero, M. Rheology and microstructure of non-colloidal suspensions under shear studied with smoothed particle hydrodynamics. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 233, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2015.12.009 (2016).

Shadloo, M. S., Oger, G. & Le Touzé, D. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics method for fluid flows, towards industrial applications: Motivations, current state, and challenges. Comput. Fluids 136, 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2016.05.029 (2016).

Swegle, J. W., Hicks, D. L. & Attaway, S. W. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics stability analysis. J. Comput. Phys. 116, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcph.1995.1010 (1995).

Su, Z., Liu, T., Yu, W., Li, X. & Graham, N. J. D. Coagulation of surface water: Observations on the significance of biopolymers. Water Res. 126, 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.09.022 (2017).

Shuai, H. High gradient magnetic separation technology and magnetic seeds. Environ. Prot. 1985, 15–18 (1985).

Yu, Y., Yang, X., Yang, J. & Jing, P. Application of magnetic separation technology in petroleum and chemical industry. Pet. Process. Petrochem. 52, 20–26 (2021).

Cundall, P. A. & Strack, O. D. L. A discrete numerical model for granular assemblies. Géotechnique 29, 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1979.29.1.47 (1979).

Johnson, K. L., Kendall, K. & Roberts, A. D. Surface energy and contact of elastic solids. Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 324, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1971.0141 (1971).

Zhu, H. P., Zhou, Z. Y., Yang, R. Y. & Yu, A. B. Discrete particle simulation of particulate systems: Theoretical developments. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62, 3378–3396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ces.2006.12.089 (2007).

Qin, S., Xu, T., Zhou, W.-H. & Bezuijen, A. Infiltration behaviour and microstructure of filter cake from sand-modified bentonite slurry. Transp. Geotech. 40, 100963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trgeo.2023.100963 (2023).

Chu, K. W., Wang, B., Yu, A. B. & Vince, A. CFD-DEM modelling of multiphase flow in dense medium cyclones. Powder Technol. 193, 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.powtec.2009.03.015 (2009).

Tong, Z. B. et al. Numerical study of the effects of particle size and polydispersity on the agglomerate dispersion in a cyclonic flow. Chem. Eng. J. 164, 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2009.11.027 (2010).

Wang, Z., Teng, Y. & Liu, M. A semi-resolved CFD–DEM approach for particulate flows with kernel based approximation and Hilbert curve based searching strategy. J. Comput. Phys. 384, 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2019.01.017 (2019).

Peng, Z., Doroodchi, E., Luo, C. & Moghtaderi, B. Influence of void fraction calculation on fidelity of CFD-DEM simulation of gas-solid bubbling fluidized beds. AIChE J. 60, 2000–2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.14421 (2014).

Lin, Y., Fang, Y. & He, C. Numerical study on clogging mechanism of slurry infiltration in porous media based on coupled CFD-DEM method. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 128, 104622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2022.104622 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No.52425807), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.52408441), the Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Innovation research team project (Grant No. 2024NSFTD0013), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (Grant No. GZC20232194).

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China, 52408441, the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF, GZC20232194, the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars, 52425807, the Sichuan Youth Science and Technology Innovation research team project, 2024NSFTD0013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.Y., Y.X., Z.Y. and W.Z. contributed to the conception of the study; Y.X. and X.C. contributed to the formal analysis; Z.Y. and Y.F. contributed to the funding acquisition; Y.F. and J.C. contributed to the investigation of the study; K.Y. contributed to the methodology; Z.Y. and X.C. contributed to the administration of the project; K.Y., Z.Y. and Y.X. performed the data analyses and wrote the manuscript; K.Y. and L.W. contributed to the review & editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ying, K., Xing, Y., Zhang, W. et al. CFD-DEM simulation of the motion law of magnetic flocs during waste slurry disposal in shield tunnel. Sci Rep 15, 5411 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86498-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86498-7